The aggregate demand curve is plotted with real output on the horizontal axis and the price level on the vertical axis. While it is theorized to be downward sloping, the Sonnenschein–Mantel–Debreu results show that the slope of the curve cannot be mathematically derived from assumptions about individual rational behavior. Instead, the downward sloping aggregate demand curve is derived with the help of three macroeconomic assumptions about the functioning of markets: Pigou's wealth effect, Keynes' interest rate effect and the Mundell–Fleming exchange-rate effect. The Pigou effect states that a higher price level implies lower real wealth and therefore lower consumption spending, giving a lower quantity of goods demanded in the aggregate. The Keynes effect states that a higher price level implies a lower real money supply and therefore higher interest rates resulting from financial market equilibrium, in turn resulting in lower investment spending on new physical capital and hence a lower quantity of goods being demanded in the aggregate.

The Mundell–Fleming exchange-rate effect is an extension of the IS–LM model. Whereas the traditional IS-LM Model deals with a closed economy, Mundell–Fleming describes a small open economy. The Mundell–Fleming model portrays the short-run relationship between an economy's nominal exchange rate, interest rate, and output (in contrast to the closed-economy IS–LM model, which focuses only on the relationship between the interest rate and output).

The aggregate demand curve illustrates the relationship between two factors: the quantity of output that is demanded and the aggregate price level. Aggregate demand is expressed contingent upon a fixed level of the nominal money supply. There are many factors that can shift the AD curve. Rightward shifts result from increases in the money supply, in government expenditure, or in autonomous components of investment or consumption spending, or from decreases in taxes.

According to the aggregate demand-aggregate supply model, when aggregate demand increases, there is movement up along the aggregate supply curve, giving a higher level of prices.

History

John Maynard Keynes in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money argued during the Great Depression that the loss of output by the private sector as a result of a systemic shock (the Wall Street Crash of 1929) ought to be filled by government spending. First, he argued that with a lower ‘effective aggregate demand’, or the total amount of spending in the economy (lowered in the Crash), the private sector could subsist on a permanently reduced level of activity and involuntary unemployment, unless there were active intervention. Business lost access to capital, so it had dismissed workers. This meant workers had less to spend as consumers, consumers bought less from business, which because of additionally reduced demand, had found the need to dismiss workers. The downward spiral could only be halted and rectified by external action. Second, people with higher incomes have a lower average propensity to consume their incomes. People with lower incomes are inclined to spend their earnings immediately to buy housing, food, transport and so forth, while people with much higher incomes cannot consume everything. They save instead, which means that the velocity of money, meaning the circulation of income through different hands in the economy, is decreased. This lowered the rate of growth. Spending should therefore target public works programmes on a large enough scale to speed up growth to its previous levels.

Components

An aggregate demand curve is the sum of individual demand curves for different sectors of the economy. The aggregate demand is usually described as a linear sum of four separable demand sources:

where

- is consumption (may also be known as consumer spending), which is given by where is consumers' income and the taxes paid by consumers,

- is investment,

- is government spending,

- is net exports, where

- is total exports, and

- total imports, given by .

These four major parts, which can be stated in either 'nominal' or 'real' terms, are:

- personal consumption expenditures () or "consumption", demand by households and unattached individuals; its determination is described by the consumption function. A basic conception is that it is the total consumption expenditures of the domestic economy. The consumption function is , where

- is autonomous consumption, the marginal propensity to consume, and the disposable income.

- gross private domestic investment (), such as spending by business firms on factory construction. This is conceived as all private sector spending aimed at the production of some future consumable.

- In Keynesian economics, not all of gross private domestic investment counts as part of aggregate demand. Much or most of the investment in inventories can be due to a short-fall in demand (unplanned inventory accumulation or "general over-production"). The Keynesian model forecasts a decrease in national output and income when there is unplanned investment. (Inventory accumulation would correspond to an excess supply of products; in the National Income and Product Accounts, it is treated as a purchase by its producer.) Thus, only the planned or intended or desired part of investment () is counted as part of aggregate demand. (So, does not include the 'investment' in running up or depleting inventory levels.)

- Investment is affected by the output and the interest rate (). Consequently, we can write it as, , a function I which takes total income and interest rate as parameters. Investment has positive relationship with the output and negative relationship with the interest rate. Thus, an increase in the interest rate will cause aggregate demand to decline. Interest costs are part of the cost of borrowing and as they rise, both firms and households will cut back on spending. This shifts the aggregate demand curve to the left. This lowers equilibrium GDP below potential GDP.

- gross government investment and consumption expenditures (), also determined as , the difference of government expenditures and taxes. An increase in government expenditures or decrease in taxes, therefore leads to an increase in GDP as government expenditures are a component of aggregate demand.

- net exports ( and sometimes ()), net demand by the rest of the world for the country's output. This contributes to the current account.

In sum, for a single country at a given time, aggregate demand ( or ) is given by .

These macroeconomic variables are constructed from varying types of microeconomic variables from the price of each, so these variables are denominated in (real or nominal) currency terms.

Aggregate demand curves

Understanding of the aggregate demand curve depends on whether it is examined based on changes in demand as income changes, or as price change.

Keynesian cross

Aggregate demand-aggregate supply model

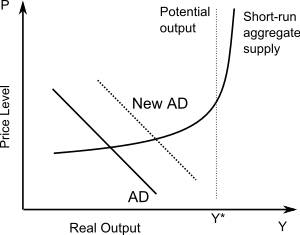

Sometimes, especially in textbooks, "aggregate demand" refers to an entire demand curve that looks like that in a typical Marshallian supply and demand diagram.

Thus, we could refer to an "aggregate quantity demanded" ( in real or inflation-corrected terms) at any given aggregate average price level (such as the GDP deflator), .

In these diagrams, typically the rises as the average price level () falls, as with the line in the diagram. The main theoretical reason for this is that if the nominal money supply (Ms) is constant, a falling implies that the real money supply ()rises, encouraging lower interest rates and higher spending. This is often called the "Keynes effect".

Carefully using ideas from the theory of supply and demand, aggregate supply can help determine the extent to which increases in aggregate demand lead to increases in real output or instead to increases in prices (inflation). In the diagram, an increase in any of the components of (at any given ) shifts the curve to the right. This increases both the level of real production () and the average price level ().

But different levels of economic activity imply different mixtures of output and price increases. As shown, with very low levels of real gross domestic product and thus large amounts of unemployed resources, most economists of the Keynesian school suggest that most of the change would be in the form of output and employment increases. As the economy gets close to potential output (), we would see more and more price increases rather than output increases as increases.

Beyond , this gets more intense, so that price increases dominate. Worse, output levels greater than cannot be sustained for long. The is a short-term relationship here. If the economy persists in operating above potential, the curve will shift to the left, making the increases in real output transitory.

At low levels of , the world is more complicated. First, most modern industrial economies experience few if any fall in prices. So the curve is unlikely to shift down or to the right. Second, when they do suffer price cuts (as in Japan), it can lead to disastrous deflation.

Debt

A post-Keynesian theory of aggregate demand emphasizes the role of debt, which it considers a fundamental component of aggregate demand; the contribution of change in debt to aggregate demand is referred to by some as the credit impulse. Aggregate demand is spending, be it on consumption, investment, or other categories. Spending is related to income via:

- Income – Spending = Net Savings

Rearranging this yields:

- Spending = Income – Net Savings = Income + Net Increase in Debt

In words: What you spend is what you earn, plus what you borrow. If you spend $110 and earned $100, then you must have net borrowed $10. Conversely, if you spend $90 and earn $100, then you have net savings of $10, or have reduced debt by $10, for a net change in debt of –$10.

If debt grows or shrinks slowly as a percentage of GDP, its impact on aggregate demand is small. Conversely, if debt is significant, then changes in the dynamics of debt growth can have significant impact on aggregate demand. Change in debt is tied to the level of debt: if the overall debt level is 10% of GDP and 1% of loans are not repaid, this impacts GDP by 1% of 10% = 0.1% of GDP, which is statistical noise. Conversely, if the debt level is 300% of GDP and 1% of loans are not repaid, this impacts GDP by 1% of 300% = 3% of GDP, which is significant: a change of this magnitude will generally cause a recession.

Similarly, changes in the repayment rate (debtors paying down their debts) impact aggregate demand in proportion to the level of debt. Thus, as the level of debt in an economy grows, the economy becomes more sensitive to debt dynamics, and credit bubbles are of macroeconomic concern. Since write-offs and savings rates both spike in recessions, both of which result in shrinkage of credit, the resulting drop in aggregate demand can worsen and perpetuate the recession in a vicious cycle.

This perspective originates in, and is intimately tied to, the debt-deflation theory of Irving Fisher, and the notion of a credit bubble (credit being the flip side of debt), and has been elaborated in the Post-Keynesian school. If the overall level of debt is rising each year, then aggregate demand exceeds Income by that amount. However, if the level of debt stops rising and instead starts falling (if "the bubble bursts"), then aggregate demand falls short of income, by the amount of net savings (largely in the form of debt repayment or debt writing off, such as in bankruptcy). This causes a sudden and sustained drop in aggregate demand, and this shock is argued to be the proximate cause of a class of economic crises, properly financial crises. Indeed, a fall in the level of debt is not necessary – even a slowing in the rate of debt growth causes a drop in aggregate demand (relative to the higher borrowing year). These crises then end when credit starts growing again, either because most or all debts have been repaid or written off, or for other reasons as below.

From the perspective of debt, the Keynesian prescription of government deficit spending in the face of an economic crisis consists of the government net dis-saving (increasing its debt) to compensate for the shortfall in private debt: it replaces private debt with public debt. Other alternatives include seeking to restart the growth of private debt ("reflate the bubble"), or slow or stop its fall; and debt relief, which by lowering or eliminating debt stops credit from contracting (as it cannot fall below zero) and allows debt to either stabilize or grow – this has the further effect of redistributing wealth from creditors (who write off debts) to debtors (whose debts are relieved).

Criticisms

Austrian theorist Henry Hazlitt argued that aggregate demand is "a meaningless concept" in economic analysis. Friedrich Hayek, another Austrian, wrote that Keynes' study of the aggregate relations in an economy is "fallacious", arguing that recessions are caused by micro-economic factors.