| Sustainable Development Goals | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mission statement | "A shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future" |

| Type of project | Non-Profit |

| Location | Global |

| Owner | Supported by United Nations & Owned by community |

| Founder | United Nations |

| Established | 2015 |

| Website | sdgs |

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or Global Goals are a collection of 17 interlinked global goals designed to be a "shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future". The SDGs were set up in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly (UN-GA) and are intended to be achieved by 2030. They are included in a UN-GA Resolution called the 2030 Agenda or what is colloquially known as Agenda 2030. The SDGs were developed in the Post-2015 Development Agenda as the future global development framework to succeed the Millennium Development Goals which were ended in 2015. The SDGs emphasize the interconnected environmental, social and economic aspects of sustainable development, by putting sustainability at their center.

The 17 SDGs are: No poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, clean water and sanitation, affordable and clean energy, decent work and economic growth, industry, innovation and infrastructure, Reduced Inequality, Sustainable Cities and Communities, Responsible Consumption and Production, Climate Action, Life Below Water, Life On Land, Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions, Partnerships for the Goals. Though the goals are broad and interdependent, two years later (6 July 2017), the SDGs were made more "actionable" by a UN Resolution adopted by the General Assembly. The resolution identifies specific targets for each goal, along with indicators that are being used to measure progress toward each target. The year by which the target is meant to be achieved is usually between 2020 and 2030. For some of the targets, no end date is given.

There are cross-cutting issues and synergies between the different goals. Cross-cutting issues include gender equality, education, culture and health. With regards to SDG 13 on climate action, the IPCC sees robust synergies, particularly for the SDGs 3 (health), 7 (clean energy), 11 (cities and communities), 12 (responsible consumption and production) and 14 (oceans). Synergies amongst the SDGs are "the good antagonists of trade-offs". Some of the known and much discussed conceptual problem areas of the SDGs include: The fact that there are competing and too many goals (resulting in problems of trade-offs), that they are weak on environmental sustainability and that there are difficulties with tracking qualitative indicators. For example, these are two difficult trade-offs to consider: "How can ending hunger be reconciled with environmental sustainability? (SDG targets 2.3 and 15.2) How can economic growth be reconciled with environmental sustainability? (SDG targets 9.2 and 9.4) "

The UN High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) is the annual space for global monitoring of the SDGs, under the auspices of the United Nations Economic and Social Council. However, it has so far failed to act as an orchestrator to promote system-wide coherence due to a lack of political leadership owing to divergent national interests. To facilitate monitoring of progress on the SDG implementation, a variety of tools exist to track and visualize this progress towards the goals. All intention is to make data more available and easily understood. For example, the "SDG Tracker", launched in June 2018, presents available data across all indicators. There were serious impacts and implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on all 17 SDGs in the year 2020. A scientific assessment released in 2022 stated that the world is not on track to achieve the SDGs by 2030 and concluded that the SDGs have so far had only limited political effects in global, national and local governance since their launch in 2015.

Adoption by the UN General Assembly

On 25 September 2015, the 193 countries of the UN General Assembly adopted the 2030 Development Agenda titled "Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development". This agenda has 92 paragraphs. Paragraph 59 outlines the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and the associated 169 targets and 232 indicators.

The SDGs were an outcome from a UN conference that was not criticized by any major non-governmental organization (NGO). Instead, the SDGs received broad support from many NGOs.

Content

Structure of goals, targets and indicators

The lists of targets and indicators for each of the 17 SDGs was published in a UN resolution in July 2017. Each goal typically has 8–12 targets, and each target has between one and four indicators used to measure progress toward reaching the targets. The targets are either "outcome" targets (circumstances to be attained) or "means of implementation" targets. The latter targets were introduced late in the process of negotiating the SDGs to address the concern of some Member States about how the SDGs were to be achieved. Goal 17 is wholly about how the SDGs will be achieved.

The numbering system of targets is as follows: "Outcome targets" use numbers, whereas "means of implementation targets" use lower case letters. For example, SDG 6 has a total of 8 targets. The first six are outcome targets and are labeled Targets 6.1 to 6.6. The final two targets are "means of implementation targets" and are labeled as Targets 6.a and 6.b.

The United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD) website provides a current official indicator list which includes all updates until the 51st session Statistical Commission in March 2020.

The indicators were classified into three tiers based on their level of methodological development and the availability of data at the global level. Tier 1 and Tier 2 are indicators that are conceptually clear, have an internationally established methodology, and data are regularly produced by at least some countries. Tier 3 indicators had no internationally established methodology or standards. The global indicator framework was adjusted so that Tier 3 indicators were either abandoned, replaced or refined. As of 17 July 2020, there were 231 unique indicators.

Reviews of indicators

The indicator framework was comprehensively reviewed at the 51st session of the United Nations Statistical Commission in 2020. It will be reviewed again in 2025. At the 51st session of the Statistical Commission (held in New York City from 3–6 March 2020) a total of 36 changes to the global indicator framework were proposed for the Commission's consideration. Some indicators were replaced, revised or deleted. Between 15 October 2018 and 17 April 2020, other changes were made to the indicators. Yet their measurement continues to be fraught with difficulties.

Listing of 17 goals with their targets and indicators

Many goals build on existing agreements and are integral parts of other political processes, such as international agreements on biodiversity, climate, oceans or standards and programs set by the International Labour Organization, the World Health Organization and so forth.

Goal 1: No poverty

SDG 1 is to: "End poverty in all its forms everywhere". Achieving SDG 1 would end extreme poverty globally by 2030. A study published in September 2020 found that poverty increased by 7 per cent in just a few months due to the COVID-19 pandemic, even though it had been steadily decreasing for the last 20 years.

The goal has seven targets and 13 indicators to measure progress. The five "outcome targets" are: eradication of extreme poverty; reduction of all poverty by half; implementation of social protection systems; ensuring equal rights to ownership, basic services, technology and economic resources; and the building of resilience to environmental, economic and social disasters. The two targets related to "means of achieving" SDG 1 are mobilization of resources to end poverty; and the establishment of poverty eradication policy frameworks at all levels.

Despite the ongoing progress, 10 percent of the world's population live in poverty and struggle to meet basic needs such as health, education, and access to water and sanitation. Extreme poverty remains prevalent in low-income countries, particularly those affected by conflict and political upheaval. In 2015, more than half of the world's 736 million people living in extreme poverty lived in Sub-Saharan Africa. Without a significant shift in social policy, extreme poverty will dramatically increase by 2030. The rural poverty rate stands at 17.2 percent and 5.3 percent in urban areas (in 2016).[29] Nearly half are children.Goal 2: Zero hunger (No hunger)

SDG 2 is to: "End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture". Globally, 1 in 9 people are undernourished, the vast majority of whom live in developing countries. Under nutrition causes wasting or severe wasting of 52 million children worldwide. It contributes to nearly half (45%) of deaths in children under five – 3.1 million children per year.

Goal 3: Good health and well-being

SDG 3 is to: "Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages". Significant strides have been made in increasing life expectancy and reducing some of the common causes of child and maternal mortality. Between 2000 and 2016, the worldwide under-five mortality rate decreased by 47 percent (from 78 deaths per 1,000 live births to 41 deaths per 1,000 live births). Still, the number of children dying under age five is very high: 5.6 million in 2016.

A 2018 study in the journal Nature found that while "nearly all African countries demonstrated improvements for children under 5 years old for stunting, wasting, and underweight... much, if not all of the continent will fail to meet the Sustainable Development Goal target—to end malnutrition by 2030".

Goal 4: Quality education

SDG 4 is to: "Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all". Major progress has been made in access to education, specifically at the primary school level, for both boys and girls. The number of out-of-school children has almost halved from 112 million in 1997 to 60 million in 2014. In terms of the progress made, global participation in tertiary education reached 224 million in 2018, equivalent to a gross enrollment ratio of 38%.

Goal 5: Gender equality

SDG 5 is to: "Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls". In 2020, representation by women in single or lower houses of national parliament reached 25 per cent, up slightly from 22 per cent in 2015. Women now have better access to decision-making positions at the local level, holding 36 per cent of elected seats in local deliberative bodies, based on data from 133 countries and areas. Whilst female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is becoming less common, at least 200 million girls and women have been subjected to this harmful practice.

Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation

SDG 6 is to: "Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all". The eight targets are measured by 11 indicators. The Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) of World Health Organisation WHO And United Nations International Children's Emergency fund UNICEF reported in 2017 that 4.5 billion people currently do not have safely managed sanitation. Also in 2017, only 71 per cent of the global population used safely managed drinking water, and 2.2 billion persons were still without safely managed drinking water. With regards to water stress: "In 2017, Central and Southern Asia and Northern Africa registered very high water stress – defined as the ratio of fresh water withdrawn to total renewable freshwater resources – of more than 70 per cent". Official development assistance (ODA) disbursements to the water sector increased to $9 billion in 2018. Evidence shows that both supply- and demand-side interventions financed by aid can contribute to promoting access to water, but consistent long-term investments are needed.

Goal 7: Affordable and clean energy

SDG 7 is to: "Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all". Progress in expanding access to electricity has been made in several countries, notably India, Bangladesh, and Kenya. The global population without access to electricity decreased to about 840 million in 2017 from 1.2 billion in 2010 (sub-Saharan Africa remains the region with the largest access deficit). Renewable energy accounted for 17.5% of global total energy consumption in 2016. Of the three end uses of renewables [electricity, heat, and transport) the use of renewables grew fastest with respect to electricity. Between 2018 and 2030, the annual average investment will need to reach approximately $55 billion to expand energy access, about $700 billion to increase renewable energy and $600 billion to improve energy efficiency.

Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth

SDG 8 is to: "Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all". Over the past five years, economic growth in least developed countries has been increasing at an average rate of 4.3 per cent. In 2018, the global growth rate of real GDP per capita was 2 per cent. In addition, the rate for least developed countries was 4.5 per cent in 2018 and 4.8 per cent in 2019, less than the 7 per cent growth rate targeted in SDG 8. In 2019, 22 per cent of the world's young people were not in employment, education or training, a figure that has hardly changed since 2005. Addressing youth employment means finding solutions with and for young people who are seeking a decent and productive job. Such solutions should address both supply, i.e. education, skills development and training, and demand. In 2018, the number of women engaged in the labor force was put at 48 per cent while that of men was 75 per cent.

Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

SDG 9 is to: "Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation". In 2019, 14% of the world's workers were employed in manufacturing activities. This percentage has not changed much since 2000. The share of manufacturing employment was the largest in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (18 percent) and the smallest in sub-Saharan Africa (6 percent). The intensity of global carbon dioxide emissions has declined by nearly one quarter since 2000, showing a general decoupling of carbon dioxide emissions from GDP growth. As at 2020, nearly the entire world population lives in an area covered by a mobile network. Millions of people are still unable to access the internet due to cost, coverage, and other reasons. It is estimated that just 53% of the world's population are currently internet users.

Goal 10: Reduced inequality

SDG 10 is to: "Reduce income inequality within and among countries". In 73 countries during the period 2012–2017, the bottom 40 per cent of the population saw its incomes grow. Still, in all countries with data, the bottom 40 per cent of the population received less than 25 per cent of the overall income or consumption. Women are more likely to be victims of discrimination than men. Among those with disabilities, 3 in 10 personally experienced discrimination, with higher levels still among women with disabilities. The main grounds of discrimination mentioned by these women was not the disability itself, but religion, ethnicity and sex, pointing to the urgent need for measures to tackle multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination. In 2019, 54 per cent of countries have a comprehensive set of policy measures to facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people.

Goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities

SDG 11 is to: "Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable". The number of slum dwellers reached more than 1 billion in 2018, or 24 per cent of the urban population. The number of people living in urban slums is highest in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Central and Southern Asia. In 2019, only half of the world's urban population had convenient access to public transport, defined as living within 500 metres' walking distance from a low-capacity transport system (such as a bus stop) and within 1 km of a high-capacity transport system (such as a railway). In the period 1990–2015, most urban areas recorded a general increase in the extent of built-up area per person.

SDG 11 has 10 targets to be achieved, and this is being measured with 15 indicators. The seven "outcome targets" include safe and affordable housing, affordable and sustainable transport systems, inclusive and sustainable urbanization, protection of the world's cultural and natural heritage, reduction of the adverse effects of natural disasters, reduction of the environmental impacts of cities and to provide access to safe and inclusive green and public spaces. The three "means of achieving" targets include strong national and regional development planning, implementing policies for inclusion, resource efficiency, and disaster risk reduction in supporting the least developed countries in sustainable and resilient building.

3.9 billion people—half of the world’s population—currently live in cities globally. It is projected that 5 billion people will live in cities by 2030. Cities across the world occupy just 3 percent of the Earth's land, yet account for 60–80 percent of energy consumption and 75 percent of carbon emissions. Increased urbanization requires increased and improved access to basic resources such as food, energy and water. In addition, basic services such as sanitation, health, education, mobility and information are needed. However, these requirements are unmet globally, which causes serious challenges for the viability and safety of cities to meet increased future demands.Goal 12: Responsible consumption and production

SDG 12 is to: "Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns". By 2019, 79 countries and the European Union have reported on at least one national policy instrument to promote sustainable consumption and production patterns. This was done to work towards the implementation of the "10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns". Global fossil fuel subsidies in 2018 were $400 billion. This was double the estimated subsidies for renewables and is detrimental to the task of reducing global carbon dioxide emissions.

To ensure that plastic products are more sustainable, thus reducing plastic waste, changes such as decreasing usage and increasing the circularity of the plastic economy are expected to be required. An increase in domestic recycling and a reduced reliance on the global plastic waste trade are other actions that might help meet the goal.

Goal 13: Climate action

SDG 13 is to: "Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts by regulating emissions and promoting developments in renewable energy". Accelerating climate actions and progress towards a just transition is essential to reducing climate risks and addressing sustainable development priorities, including water, food and human security (robust evidence, high agreement). Accelerating action in the context of sustainable development involves not only expediting the pace of change (speed) but also addressing the underlying drivers of vulnerability and high emissions (quality and depth of change) and enabling diverse communities, sectors, stakeholders, regions and cultures (scale and breadth of change) to participate in just, equitable and inclusive processes that improve the health and well-being of people and the planet.

The decade between 2010 - 2019 was the warmest decade recorded in history. Currently climate change is affecting the global community in every nation across the world. The impact of climate change not only impacts national economies, but also lives and livelihoods, especially those in vulnerable conditions. By 2018, climate change continued exacerbating the frequency of natural disasters, such as massive wildfires, droughts, hurricanes, and floods. Over the period 2000–2018, the greenhouse emissions of developed countries in transitions have declined by 6.5%. However, the emissions of the developing countries are up by 43% in the period between 2000 and 2013. In 2019, at least 120 of 153 developing countries had undertaken activities to formulate and implement national adaptation plans.

SDG 13 and SDG 7 on clean energy are closely related and complementary. The leading sources of the greenhouse gas savings that countries need to focus on in order to realize their commitments under the Paris Agreement are switching fuels to renewable energy and enhancing end-use energy efficiency.Goal 14: Life below water

SDG 14 is to: "Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development". The current efforts to protect oceans, marine environments and small-scale fishers are not meeting the need to protect the resources. One of the key drivers of global overfishing is illegal fishing. It threatens marine ecosystems, puts food security and regional stability at risk, and is linked to major human rights violations and even organized crime. Increased ocean temperatures and oxygen loss act concurrently with ocean acidification and constitute the "deadly trio" of climate change pressures on the marine environment.

One indicator (14.1.1b) under Goal 14 specifically relates to reducing impacts from marine plastic pollution.

The first seven targets are "outcome targets": Reduce marine pollution; protect and restore ecosystems; reduce ocean acidification; sustainable fishing; conserve coastal and marine areas; end subsidies contributing to overfishing; increase the economic benefits from sustainable use of marine resources. The last three targets are "means of achieving" targets: To increase scientific knowledge, research and technology for ocean health; support small scale fishers; implement and enforce international sea law.

Oceans and fisheries support the global population's economic, social and environmental needs. Oceans are the source of life of the planet and the global climate system regulator. They are the world's largest ecosystem, home to nearly a million known species. Oceans cover more than two-thirds of the earth's surface and contain 97% of the planet's water. They are essential for making the planet livable. Rainwater, drinking water and climate are all regulated by ocean heat content and currents. Over 3 billion people depend on marine life for their livelihood. However, there has been a 26 percent increase in acidification since the industrial revolution. Effective strategies to mitigate adverse effects of increased ocean acidification are needed to advance the sustainable use of oceans.Goal 15: Life on land

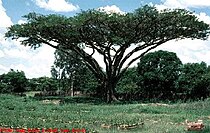

SDG 15 is to: "Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss". The proportion of forest area fell, from 31.9 per cent of total land area in 2000 to 31.2 per cent in 2020, representing a net loss of nearly 100 million ha of the world's forests. This was due to decreasing forest area decreased in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and South-Eastern Asia, driven by deforestation for agriculture. Desertification affects as much as one-sixth of the world's population, 70% of all drylands, and one-quarter of the total land area of the world. It also leads to spreading poverty and the degradation of billion hectares of cropland. A report in 2020 stated that globally, the species extinction risk has worsened by about 10 per cent over the past three decades.

The nine "outcome targets" include: Conserve and restore terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems; end deforestation and restore degraded forests; end desertification and restore degraded land; ensure conservation of mountain ecosystems, protect biodiversity and natural habitats; protect access to genetic resources and fair sharing of the benefits; eliminate poaching and trafficking of protected species; prevent invasive alien species on land and in water ecosystems; and integrate ecosystem and biodiversity in governmental planning. The three "means of achieving targets" include: Increase financial resources to conserve and sustainably use ecosystem and biodiversity; finance and incentivize sustainable forest management; combat global poaching and trafficking.

Humans depend on earth and the oceans to live. This goal aims at securing sustainable livelihoods that will be enjoyed for generations to come. The human diet is composed 80% of plant life, which makes agriculture a prime economic resource. Forests cover 30 percent of the Earth's surface, provide vital habitats for millions of species, and important sources for clean air and water, as well as being crucial for combating climate change.Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions

SDG 16 is to: "Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels". With more than a quarter of children under 5 unregistered worldwide as of 2015, about 1 in 5 countries will need to accelerate progress to achieve universal birth registration by 2030. Data from 38 countries over the past decade suggest that high-income countries have the lowest prevalence of bribery (an average of 3.7 per cent), while lower-income countries have high levels of bribery when accessing public services (22.3 per cent).

The goal has ten "outcome targets": Reduce violence; protect children from abuse, exploitation, trafficking and violence; promote the rule of law and ensure equal access to justice; combat organized crime and illicit financial and arms flows, substantially reduce corruption and bribery; develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions; ensure responsive, inclusive and representative decision-making; strengthen the participation in global governance; provide universal legal identity; ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms. There are also two "means of achieving targets": Strengthen national institutions to prevent violence and combat crime and terrorism; promote and enforce non-discriminatory laws and policies.

Reducing violent crime, sex trafficking, forced labor, and child abuse are clear global goals. The International Community values peace and justice; they call for stronger judicial systems that will enforce laws and work toward a more peaceful and just society. All women need to be able to turn to fair and effective institution to access Justice and important services. We cannot hope for sustainable development without peace and stability in any country.Goal 17: Partnership for the goals

SDG 17 is to: "Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development". This goal has 19 outcome targets and 24 indicators. Increasing international cooperation is seen as vital to achieving each of the 16 previous goals. Goal 17 is included to assure that countries and organizations cooperate instead of compete. Developing multi-stakeholder partnerships to share knowledge, expertise, technology, and financial support is seen as critical to overall success of the SDGs. The goal encompasses improving north–south and South-South cooperation, and public-private partnerships which involve civil societies are specifically mentioned.

With US$5 trillion to $7 trillion in annual investment required to achieve the SDGs, total official development assistance reached US$147.2 billion in 2017. This, although steady, is below the set target. In 2016, six countries met the international target to keep official development assistance at or above 0.7 percent of gross national income. Humanitarian crises brought on by conflict or natural disasters have continued to demand more financial resources and aid. Even so, many countries also require official development assistance to encourage growth and trade.

Cross-cutting issues and synergies

To achieve sustainable development, three aspects or dimensions need to come together: The economic, socio-political, and environmental dimensions are all critically important and interdependent. Progress will require multidisciplinary and trans-disciplinary research across all three sectors. This proves difficult when major governments fail to support it. Sustainable development can enhance sectoral integration and social inclusion (robust evidence, high agreement). Inclusion merits attention because equity within and across countries is critical to transitions that are not simply rapid but also sustainable and just. Resource shortages, social divisions, inequitable distributions of wealth, poor infrastructure and limited access to advanced technologies can constrain the options and capacities for developing countries to achieve sustainable and just transitions (medium evidence, high agreement) {17.1.1.2}.

According to the UN, the target is to reach the community farthest behind. Commitments should be transformed into effective actions requiring a correct perception of target populations. Data or information must address all vulnerable groups such as children, elderly folks, persons with disabilities, refugees, indigenous peoples, migrants, and internally-displaced persons.

Cross cutting issues include for example gender equality, education, culture and health. These are just some examples of various interlinkages inherent in the SDGs.

Gender equality

The widespread consensus is that progress on all of the SDGs will be stalled if women's empowerment and gender equality are not prioritized, and treated holistically. The SDGs look to policy makers as well as private sector executives and board members to work toward gender equality. Statements from diverse sources, such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), UN Women and the World Pensions Forum, have noted that investments in women and girls have positive impacts on economies. National and global development investments in women and girls often exceed their initial scope.

Gender equality is mainstreamed throughout the SDG framework by ensuring that as much sex-disaggregated data as possible are collected.

Education

Education for sustainable development (ESD) is explicitly recognized in the SDGs as part of Target 4.7 of the SDG on education. UNESCO promotes the Global Citizenship Education (GCED) as a complementary approach. At the same time, it is important to emphasize ESD's importance for all the other 16 SDGs. With its overall aim to develop cross-cutting sustainability competencies in learners, ESD is an essential contribution to all efforts to achieve the SDGs. This would enable individuals to contribute to sustainable development by promoting societal, economic and political change as well as by transforming their own behavior.

Culture

Culture is explicitly referenced in SDG 11 Target 4 ("Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world's cultural and natural heritage"). However, culture is seen as a cross-cutting theme because it impacts several SDGs. For example, culture plays a role in SDGs related to:

- environment and resilience (Targets 11.4 Cultural & natural heritage, 11.7 Inclusive public spaces, 12.b Sustainable tourism management, 16.4 Recovery of stolen assets),

- prosperity and livelihoods (Targets 8.3 Jobs, entrepreneurship & innovation; 8.9 Policies for sustainable tourism),

- knowledge and skills,

- inclusion and participation (Targets 11.7 Inclusive public spaces, 16.7 Participatory decision-making).

Health

SDGs 1 to 6 directly address health disparities, primarily in developing countries. These six goals address key issues in Global Public Health, Poverty, Hunger and Food security, Health, Education, Gender equality and women's empowerment, and water and sanitation. Public health officials can use these goals to set their own agenda and plan for smaller scale initiatives for their organizations. These goals are designed to lessen the burden of disease and inequality faced by developing countries and lead to a healthier future.

The links between the various sustainable development goals and public health are numerous and well established:

- Living below the poverty line is attributed to poorer health outcomes and can be even worse for persons living in developing countries where extreme poverty is more common. A child born into poverty is twice as likely to die before the age of five compared to a child from a wealthier family.

- The detrimental effects of hunger and malnutrition that can arise from systemic challenges with food security are enormous. The World Health Organization estimates that 12.9 percent of the population in developing countries is undernourished.

- Health challenges in the developing world are enormous, with "only half of the women in developing nations receiving the recommended amount of healthcare they need.

- Educational equity has yet to be reached in the world. Public health efforts are impeded by this, as a lack of education can lead to poorer health outcomes. This is shown by children of mothers who have no education having a lower survival rate compared to children born to mothers with primary or greater levels of education. Cultural differences in the role of women vary by country, many gender inequalities are found in developing nations. Combating these inequalities has shown to also lead to a better public health outcome.

- In studies done by the World Bank on populations in developing countries, it was found that when women had more control over household resources, the children benefit through better access to food, healthcare, and education.

- Basic sanitation resources and access to clean sources of water are a basic human right. However, 1.8 billion people globally use a source of drinking water that is contaminated by feces, and 2.4 billion people lack access to basic sanitation facilities like toilets or pit latrines. A lack of these resources is what causes approximately 1000 children a day to die from diarrheal diseases that could have been prevented from better water and sanitation infrastructure.

Synergies

Synergies amongst the SDGs are "the good antagonists of trade-offs". With regards to SDG 13 on climate action, the IPCC sees robust synergies particularly for the SDGs 3 (health), 7 (clean energy), 11 (cities and communities), 12 (responsible consumption and production) and 14 (oceans).

To meet SDG 13 and other SDGs, sustained long-term investment in green innovation is required: to decarbonize the physical capital stock – energy, industry, and transportation infrastructure – and ensure its resilience to a changing future climate; to preserve and enhance natural capital – forests, oceans, and wetlands; and to train people to work in a climate-neutral economy.

Conceptual problem areas

Competing and too many goals

A commentary in The Economist in 2015 argued that 169 targets for the SDGs is too many, describing them as "sprawling, misconceived" and "a mess" compared to the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The goals are said to ignore local context. All other 16 goals might be contingent on achieving SDG 1, ending poverty, which should have been at the top of a very short list of goals.

The trade-offs among the 17 SDGs are a difficult barrier to sustainability and might even prevent their realization. For example these are three difficult trade-offs to consider: "How can ending hunger be reconciled with environmental sustainability? (SDG targets 2.3 and 15.2) How can economic growth be reconciled with environmental sustainability? (SDG targets 9.2 and 9.4) How can income inequality be reconciled with economic growth? (SDG targets 10.1 and 8.1)."

Weak on environmental sustainability

Scholars have criticized that the Sustainable Development Goals fail to recognize that planetary, people and prosperity concerns are all part of one earth system, and that the protection of planetary integrity should not be a means to an end, but an end in itself. A principal concern is that the SDGs remain fixated on the idea that economic growth is foundational to achieve all pillars of sustainable development. Doubts about the steering qualities of the SDGs towards environmental protection arise not only from their ability to steer, but also from the fact that they do not seem to prioritize environmental protection in the first place.

There is no overarching environmental or "planetary" goal. Instead, environmental protection is left to a cluster of environment-focused SDGs down the list at Goal 13, 14 and 15. While including these explicit environmental goals might advance environmental protection, some also argue that Goals 13, 14 and 15 could compartmentalize environmental issues (climate, land and oceans). The goals do not pursue planetary integrity as such, but do recognize the importance of protecting environmental aspects such as climate, land and the oceans.

The SDGs may simply maintain the status quo and fall short of delivering on the ambitious development agenda. The current status quo has been described as "separating human wellbeing and environmental sustainability, failing to change governance and to pay attention to trade-offs, root causes of poverty and environmental degradation, and social justice issues".

Continued global economic growth of 3 percent (Goal 8) may not be reconcilable with ecological sustainability goals, because the required rate of absolute global eco-economic decoupling is far higher than any country has achieved in the past. Anthropologists have suggested that, instead of targeting aggregate GDP growth, the goals could target resource use per capita, with "substantial reductions in high‐income nations."

Environmental constraints and planetary boundaries are underrepresented within the SDGs. For instance, the way the current SDGs are structured leads to a negative correlation between environmental sustainability and SDGs. This means, as the environmental sustainability side of the SDGs is underrepresented, the resource security for all, particularly for lower-income populations, is put at risk. This is not a criticism of the SDGs per se, but a recognition that their environmental conditions are still weak.

The SDGs have been criticized for their inability to protect biodiversity. They could unintentionally promote environmental destruction in the name of sustainable development.

Scientists have proposed several ways to address the weaknesses regarding environmental sustainability in the SDGs:

- The monitoring of essential variables to better capture the essence of coupled environmental and social systems that underpin sustainable development, helping to guide coordination and systems transformation.

- More attention to the context of the biophysical systems in different places (e.g., coastal river deltas, mountain areas)

- Better understanding of feedbacks across scales in space (e.g., through globalization) and time (e.g., affecting future generations) that could ultimately determine the success or failure of the SDGs.

Ethical orientation

There are concerns about the ethical orientation of the SDGs: their focus seems to remain on "growth and use of resources ... and [it] departs from an individual, not collective, point of view"; and they remain "underpinned by strong (Western) modernist notions of development: sovereignty of humans over their environment (anthropocentricism), individualism, competition, freedom (rights rather than duties), self-interest, belief in the market leading to collective welfare, private property (protected by legal systems), rewards based on merit, materialism, quantification of value, and instrumentalization of labor".

Difficulties with tracking qualitative indicators

Regarding the targets of the SDGs, there is generally weak evidence linking the "means of implementation" to outcomes. The targets about "means of implementation" (those denoted with a letter, for example, Target 6.a) are imperfectly conceptualized and inconsistently formulated, and tracking their largely qualitative indicators will be difficult.

Difficulties in achieving impact

There is a lack of impact of the SDGs so far, especially in the are of protecting planetary integrity. Some design elements might have been flawed from the start, such as the number of goals, the structure of the goal framework (for example, the non-hierarchical structure), the coherence between the goals, the specificity or measurability of the targets, the language used in the text, and their reliance on neoliberal economic development-oriented sustainable development as their core orientation.

Some argue that the SDGs' focus on sustainable economic development is inevitably detrimental to planetary integrity and justice, which require both limits to economic growth and the removal of ‘developmental’ disparities between the rich and the poor.

In 2016, the UN ordered an analysis on the reception of the name "the 17 Sustainable Development Goals" with the communication bureau Trollback. It was found out that the word "sustainable" lead to confusion, it made the whole name confusingly long too, so it was rebranded into the "17 Global Goals".

Monitoring mechanism

UN High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF)

As part of a larger reform, governments decided to terminate the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development and to establish in its place a High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. This new forum was meant to function as a regular meeting place for governments and non-state representatives to assess global progress towards sustainable development. The creation of this overarching institution for sustainability governance was also expected to enhance system-wide coherence in the follow-up and progress reviews under the 2030 Agenda.

The UN High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) is the annual space for global monitoring of the SDGs, under the auspices of the United Nations economic and Social Council. In July 2020 the meeting took place online for the first time due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The theme was "Accelerated action and transformative pathways: realizing the decade of action and delivery for sustainable development" and a ministerial declaration was adopted.

High-level progress reports for all the SDGs are published in the form of reports by the United Nations Secretary General. The most recent one is from April 2020.

The literature indicates that the High-level Political Forum has failed to act as an orchestrator to promote system-wide coherence. The reasons for this include its broad and unclear mandate combined with a lack of resources and a lack of political leadership owing to divergent national interests.[10]: 206 Attempts to strengthen the role of the HLPF and to harmonize the voluntary reporting system have not found consensus among governments. This reporting system remains a soft peer-learning mechanism of governments that might even lead to uncontested endorsements of national performances if civil society organizations are not able to act as watchdogs in policy implementation.

Monitoring tools and websites

The online publication SDG-Tracker was launched in June 2018 and presents data across all available indicators. It relies on the Our World in Data database and is also based at the University of Oxford. The publication has global coverage and tracks whether the world is making progress towards the SDGs. It aims to make the data on the 17 goals available and understandable to a wide audience.

The website "allows people around the world to hold their governments accountable to achieving the agreed goals". The SDG-Tracker highlights that the world is currently (early 2019) very far away from achieving the goals.

The Global "SDG Index and Dashboards Report" is the first publication to track countries' performance on all 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The annual publication, co-produced by Bertelsmann Stiftung and SDSN, includes a ranking and dashboards that show key challenges for each country in terms of implementing the SDGs. The publication features trend analysis to show how countries performing on key SDG metrics have changed over recent years in addition to an analysis of government efforts to implement the SDGs.

Reporting on progress

Overall status

Overall status reports made the following statements regarding achieving the SDGs:

- A study stated in 2022: "Recent assessments show that, under current trends, the world’s social and natural biophysical systems cannot support the aspirations for universal human well-being embedded in the SDGs."

- The UN Global Sustainable Development Report in 2019 found that: "The world is not on track for achieving most of the 169 targets that comprise the Goals". Several dimensions with cross-cutting impacts across the SDGs are not even moving in the right direction: rising inequalities, climate change, biodiversity loss and increasing amounts of waste from human activity.

A report in 2020 found that due to many economic and social issues, many countries are seeing a major decline in the progress made. In Asia for example, data shows a loss of progress on goals 2,8,10,11, and 15. Recommended approaches to achieve the SDGs are: "Set priorities, focus on harnessing the environmental dimension of the SDGs, understand how the SDGs work as an indivisible system, and look for synergies".

Assessing the political impact of the SDGs

A scientific assessment released in 2022 reviewed over 3,000 scientific articles, mainly from the social sciences. The review found that the world is not on track to achieve the SDGs by 2030 and concluded that the SDGs have so far had only limited political effects in global, national and local governance since their launch in 2015. The authors also state that the SDGs had some positive effects on actors and institutions. There is some evidence that the Sustainable Development Goals have influenced institutions, policies and debates, from global governance to local politics. While this impact has so far largely been discursive, the goals had some normative and institutional effects as well.

Experiences from the implementation of the SDGs in domestic, regional and international contexts reveal little evidence of steering effects towards advancing planetary integrity. This is because all countries largely prioritize the socio-economic SDGs over environmental ones, following their earlier national development policies. Whatever indirect steering effects the SDGs might have in this respect are merely implied through the environmental goals at the bottom of the list of the SDGs (Goal 14 and 15).

There is even emerging evidence that the SDGs might have even adverse effects, by providing a "smokescreen of hectic political activity" that blurs a reality of stagnation, dead ends and business-as-usual. In this perspective, the goals could be seen as a legitimizing meta-narrative that helps international organizations, governments and corporations to merely pretend to be taking decisive action to address the concerns of citizens while clinging to the status quo.

Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 had impacts on all 17 goals. It has become "the worst human and economic crisis in a lifetime". The pandemic threatened progress made in particular for SDG 3 (health), SDG 4 (education), SDG 6 (water and sanitation for all), SDG 10 (reduce inequality) and SDG 17 (partnerships).

Uneven priorities of goals

In 2019 five progress reports on the 17 SDGs were published. Three came from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), one from the Bertelsmann Foundation and one from the European Union. A review of the five reports analyzed which of the 17 Goals were addressed in priority and which ones were left behind. In explanation of the findings, the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics said Biodiversity, Peace and Social Inclusion were "left behind" by quoting the official SDGs motto "Leaving no one behind".

It has been argued that governments and businesses actively prioritize the social and economic goals over the environmental goals (such as Goal 14 and 15) in both rhetoric and practice.

| SDG Topic | Rank | Average Rank | Mentions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 1 | 3.2 | 1814 |

| Energy Climate Water |

2 | 4.0 | 1328 1328 1784 |

| Education | 3 | 4.6 | 1351 |

| Poverty | 4 | 6.2 | 1095 |

| Food | 5 | 7.6 | 693 |

| Economic Growth | 6 | 8.6 | 387 |

| Technology | 7 | 8.8 | 855 |

| Inequality | 8 | 9.2 | 296 |

| Gender Equality | 9 | 10.0 | 338 |

| Hunger | 10 | 10.6 | 670 |

| Justice | 11 | 10.8 | 328 |

| Governance | 12 | 11.6 | 232 |

| Decent Work | 13 | 12.2 | 277 |

| Peace | 14 | 12.4 | 282 |

| Clean Energy | 15 | 12.6 | 272 |

| Life on Land | 16 | 14.4 | 250 |

| Life below Water | 17 | 15.0 | 248 |

| Social Inclusion | 18 | 16.4 | 22 |

Implementation

Implementation of the SDGs started worldwide in 2016. This process can also be called "Localizing the SDGs". In 2019 António Guterres (secretary-general of the United Nations) issued a global call for a "Decade of Action" to deliver the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. This decade will last from 2020 to 2030. The secretary general of the UN will convene an annual platform for driving the Decade of Action.

Actors

There are four types of actors for implementation of the SDGs: national governments, sub-national authorities, corporations and civil society. All these types of actors are engaged – to differing extents – in implementing the SDGs. Civil society participation and empowerment is routinely promoted as a silver bullet, while not acknowledging the plurality and diverse interests and agendas that exist in this group.

Many governments seem to be committed to the SDGs, and some adjust administrative units or create formal coordinating arrangements. However, such new institutions often seem to reproduce existing structures and priorities. Especially for governments in the Global South with limited fiscal space it is often difficult to reallocate national budgets.

Discursive effects of implementing the Sustainable Development Goals at multiple levels are more dominant, while resource effects are observed the least. Across all actors, however, relationship building is an important motivation for actors to engage with the Sustainable Development Goals. But even with new partnerships, the voluntary nature of the framework makes it easy for incumbent actors to implement the Sustainable Development Goals only in ways that benefit their interests.

Costs

Cost estimates

The United Nations estimates that for Africa, considering the continent's population growth, yearly funding of $1.3 trillion would be needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in Africa. The International Monetary Fund also estimates that $50 billion may be needed only to cover the expenses of climate adaptation.

Estimates for providing clean water and sanitation for the whole population of all continents have been as high as US$200 billion. The World Bank says that estimates need to be made country by country, and reevaluated frequently over time.

In 2014, UNCTAD estimated the annual costs to achieving the UN Goals at US$2.5 trillion per year. Another estimate from 2018 (by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics, that conducts the World Social Capital Monitor) found that to reach all of the SDGs this would require between US$2.5 and $5.0 trillion per year.

Allocation of funds

There is hardly any evidence that governments significantly reallocate funding to implement the Sustainable Development Goals, neither for national implementation nor international cooperation. The global goals do not seem to have changed public budgets and financial allocation mechanisms in any significant way. Lack of funding could prevent genuine steering effects of the Sustainable Development Goals and indicate that the discursive changes that stem from the SDG process will not lead to transformative structural change and policy reform.

In 2019 António Guterres called for the following priorities with regards to allocation of funds: "a major surge in financing with Member States meeting their official development assistance commitments; fully replenishing Global Funds on Climate and Health; boosting funding for education and other Sustainable Development Goals; supporting innovative forms of financing like Social Impact Bonds; and increasing access to technologies and concessional and green finance for countries most at risk".

The Rockefeller Foundation asserts that "The key to financing and achieving the SDGs lies in mobilizing a greater share of the $200+ trillion in annual private capital investment flows toward development efforts, and philanthropy has a critical role to play in catalyzing this shift." Large-scale funders participating in a Rockefeller Foundation-hosted design thinking workshop concluded that "while there is a moral imperative to achieve the SDGs, failure is inevitable if there aren't drastic changes to how we go about financing large scale change".

In 2017 the UN launched the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development (UN IATF on FfD) that invited to a public dialogue. The top-5 sources of financing for development were estimated in 2018 to be: Real new sovereign debt OECD countries, military expenditures, official increase sovereign debt OECD countries, remittances from expats to developing countries, official development assistance (ODA).

SDG-driven investment

There is growing evidence that some corporate actors, including banks and investors, engage and invest in sustainability practices, promote green finance, facilitate large-scale sustainable infrastructure projects or expand their loan portfolios to environmental and social loans. Such practices are often discursively linked to the Sustainable Development Goals. Some studies warn here of "SDG washing" by corporate actors, selective implementation of the goals, and the political risks linked to private investments in the context of continued shortage of public funding.

Capital stewardship is expected to play a crucial part in the progressive advancement of the SDG agenda to "shift the economic system towards sustainable investment by using the SDG framework across all asset classes".

In 2017, 2018 and early 2019, the World Pensions Council (WPC) held a series of ESG-focused discussions with pension board members (trustees) and senior investment executives from across G20 nations in Toronto, London (with the UK Association of Member-Nominated Trustees, AMNT), Paris and New York – notably on the sidelines of the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly. Many pension investment executives and board members confirmed they were in the process of adopting or developing SDG-informed investment processes, with more ambitious investment governance requirements – notably when it comes to climate action, gender equality and social fairness: “they straddle key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including, of course, Gender Equality (SDG 5) and Reduced Inequality (SDG 10) [...] Many pension trustees are now playing for keeps”.

The notion of "SDG Driven Investment" gained further ground amongst institutional investors in the second semester of 2019, notably at the WPC-led G7 Pensions Roundtable held in Biarritz, 26 August 2019, and the Business Roundtable held in Washington, DC, on 19 August 2019.

Communication and advocacy

UN agencies which are part of the United Nations Development Group decided to support an independent campaign to communicate the new SDGs to a wider audience. This campaign, "Project Everyone," had the support of corporate institutions and other international organizations.

Using the text drafted by diplomats at the UN level, a team of communication specialists developed icons for every goal. They also shortened the title "The 17 Sustainable Development Goals" to "Global Goals/17#GlobalGoals," then ran workshops and conferences to communicate the Global Goals to a global audience.

An early concern was that 17 goals would be too much for people to grasp and that therefore the SDGs would fail to get a wider recognition. Without wider recognition the necessary momentum to achieve them by 2030 would not be achieved. Concerned with this, British film-maker Richard Curtis started the organization in 2015 called Project Everyone with the aim to bring the goals to everyone on the planet. Curtis approached Swedish designer Jakob Trollbäck who rebranded them as The Global Goals and created the 17 iconic visuals with clear short names as well as a logotype for the whole initiative. The communication system is available for free. In 2018, Jakob Trollbäck and his company (The New Division), went on to extend the communication system to also include the 169 targets that describe how the goals can be achieved.

The benefits of engaging the affected public in decision making that affects their livelihoods, communities, and environment have been widely recognized. The Aarhus Convention is a United Nations convention passed in 2001, explicitly to encourage and promote effective public engagement in environmental decision making. Information transparency related to social media and the engagement of youth are two issues related to the Sustainable Development Goals that the convention has addressed.

Advocates

In 2019, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres appointed SDG advocates. The role of the public figures is to raise awareness, inspire greater ambition, and push for faster action on the SDGs. They are:

- Co-Chairs

- Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, President of Ghana.

- Erna Solberg, Prime Minister of Norway.

- Members

- Queen Mathilde of the Belgians

- Muhammadu Sanusi II, Emir of Kano.

- Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, founder of the Education Above All Foundation.

- Richard Curtis, screenwriter, producer and film director.

- Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, environmental and indigenous rights activist.

- Jack Ma, founder and executive chairman of the Alibaba Group.

- Graça Machel, founder of Graça Machel Trust.

- Dia Mirza, actress, film producer, and UN Environment Program Goodwill Ambassador for India.

- Alaa Murabit, founder of The Voice of Libyan Women.

- Nadia Murad, Nobel Laureate, chair and president of Nadia's Initiative, UN Office on Drugs and Crime Goodwill Ambassador.

- Edward Ndopu, founder of Global Strategies on Inclusive Education.

- Paul Polman, chair of the International Chamber of Commerce, vice-chair of the board of United Nations Global Compact.

- Jeffrey Sachs, director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University.

- Marta Vieira da Silva, footballer for Orlando Pride and UN Women Goodwill Ambassador.

- Forest Whitaker, actor, founder and CEO of Whitaker Peace & Development Initiative.

- Hamdi Ulukaya, founder of Chobani

Global events

Global Goals Week

Global Goals Week is an annual week-long event in September for action, awareness, and accountability for the Sustainable Development Goals. Its a shared commitment for over 100 partners to ensure quick action on the SDGs by sharing ideas and transformative solutions to global problems. It first took place in 2016. It is often held concurrently with Climate Week NYC.

Film festivals

The annual "Le Temps Presse" festival in Paris utilizes cinema to sensitize the public, especially young people, to the Sustainable Development Goals. The origin of the festival was in 2010 when eight directors produced a film titled "8," which included eight short films, each featuring one of the Millennium Development Goals. After 2.5 million viewers saw "8" on YouTube, the festival was created. It now showcases young directors whose work promotes social, environmental and human commitment. The festival now focuses on the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Arctic Film Festival is an annual film festival organized by HF Productions and supported by the SDGs' Partnership Platform. Held for the first time in 2019, the festival is expected to take place every year in September in Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway.

History

In 1972, governments met in Stockholm, Sweden, for the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment to consider the rights of the family to a healthy and productive environment. In 1983, the United Nations created the World Commission on Environment and Development (later known as the Brundtland Commission), which defined sustainable development as "meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs". In 1992, the first United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) or Earth Summit was held in Rio de Janeiro, where the first agenda for Environment and Development, also known as Agenda 21, was developed and adopted.

In 2012, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD), also known as Rio+20, was held as a 20-year follow up to UNCED. Colombia proposed the idea of the SDGs at a preparation event for Rio+20 held in Indonesia in July 2011. In September 2011, this idea was picked up by the United Nations Department of Public Information 64th NGO Conference in Bonn, Germany. The outcome document proposed 17 sustainable development goals and associated targets. In the run-up to Rio+20 there was much discussion about the idea of the SDGs. At the Rio+20 Conference, a resolution known as "The Future We Want" was reached by member states. Among the key themes agreed on were poverty eradication, energy, water and sanitation, health, and human settlement.

The Rio+20 outcome document mentioned that "at the outset, the OWG [Open Working Group] will decide on its methods of work, including developing modalities to ensure the full involvement of relevant stakeholders and expertise from civil society, Indigenous Peoples, the scientific community and the United Nations system in its work, in order to provide a diversity of perspectives and experience".

In January 2013, the 30-member UN General Assembly Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals was established to identify specific goals for the SDGs. The Open Working Group (OWG) was tasked with preparing a proposal on the SDGs for consideration during the 68th session of the General Assembly, September 2013 – September 2014. On 19 July 2014, the OWG forwarded a proposal for the SDGs to the Assembly. After 13 sessions, the OWG submitted their proposal of 8 SDGs and 169 targets to the 68th session of the General Assembly in September 2014. On 5 December 2014, the UN General Assembly accepted the Secretary General's Synthesis Report, which stated that the agenda for the post-2015 SDG process would be based on the OWG proposals.

Ban Ki-moon, the United Nations Secretary-General from 2007 to 2016, has stated in a November 2016 press conference that: "We don't have plan B because there is no planet B."[185] This thought has guided the development of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Post-2015 Development Agenda was a process from 2012 to 2015 led by the United Nations to define the future global development framework that would succeed the Millennium Development Goals. The SDGs were developed to succeed the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) which ended in 2015. The gaps and shortcomings of MDG Goal 8 (To develop a global partnership for development) led to identifying a problematic "donor-recipient" relationship. Instead, the new SDGs favor collective action by all countries.

The UN-led process involved its 193 Member States and global civil society. The resolution is a broad intergovernmental agreement that acts as the Post-2015 Development Agenda. The SDGs build on the principles agreed upon in Resolution A/RES/66/288, entitled "The Future We Want". This was a non-binding document released as a result of Rio+20 Conference held in 2012.

Negotiations on the Post-2015 Development Agenda began in January 2015 and ended in August 2015. The negotiations ran in parallel to United Nations negotiations on financing for development, which determined the financial means of implementing the Post-2015 Development Agenda; those negotiations resulted in adoption of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda in July 2015.

Country examples

Asia and Pacific

Australia

The Commonwealth of Australia was one of the 193 countries that adopted the 2030 Agenda in September 2015. Implementation of the agenda is led by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) with different federal government agencies responsible for each of the goals. Australia is not on-track to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Four modelled scenarios based on different development approaches found that the 'Sustainability Transition' scenario could deliver "rapid and balanced progress of 70% towards SDG targets by 2020, well ahead of the business-as-usual scenario (40%)". In 2020, Australia's overall performance in the SDG Index is ranked 37th out of 166 countries (down from 18th out of 34 countries in 2015).

Bangladesh

Bangladesh, as an active participant in the global process of preparing the Agenda 2030, started its implementation from the very beginning through the integration of SDGs into the national development agenda. The SDGs were integrated with the country's 7th Five Year Plan (7FYP, 2016- 2020) and these were given emphasis while setting the priority areas of the 7FYP such that the achievement of Plan objectives and targets also can contribute towards the achievement of the SDGs. All the 17 goals were integrated into the 7FYP. A Development Results Framework (DRF)- -a robust and rigorous result based monitoring and evaluation framework—was also embedded in the Plan for monitoring the 7FYP. The outcomes and targets in the DRF were aligned with the SDGs focus on macroeconomic development, poverty reduction, employment, education, health, water and sanitation, transport and communication, power, energy and mineral resources, gender and inequality, environment, climate change and disaster management, ICT, urban development, governance, and international cooperation and partnership.

Bhutan

The Sustainable development process in Bhutan has a more meaningful purpose than economic growth alone. The nation's holistic goal is the pursuit of Gross National Happiness (GNH), a term coined in 1972 by the Fourth King of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, which has the principal guiding philosophy for the long term journey as a nation. Therefore, the SDGs find a natural place within the framework of GNH sharing a common vision of prosperity, peace, and harmony where no one is left behind. Just as GNH is both an ideal to be pursued and a practical tool so too the SDGs inspire and guide sustainable action. Guided by the development paradigm of GNH, Bhutan is committed to achieving the goals of SDGs by 2030 since its implementation in September 2015. In line with Bhutan's commitment to the implementation of the SDGs and sustainable development, Bhutan has participated in the Voluntary National Review in the 2018 High-Level Political Forum. As the country has progressed in its 12th five-year plan (2019–2023), the national goals have been aligned with the SDGs and every agency plays a vital role in its own ways to collectively achieving the committed goals of SDGs.

India

The Government of India established the NITI Aayog to attain sustainable development goals. In March 2018 Haryana became the first state in India to have its annual budget focused on the attainment of SDG with a 3-year action plan and a 7-year strategy plan to implement sustainable development goals when Captain Abhimanyu, Finance Minister of Government of Haryana, unveiled a ₹1,151,980 lakh (equivalent to ₹130 billion, US$1.6 billion or €1.6 billion in 2020) annual 2018-19 budget. Also, NITI Aayog starts the exercise of measuring India and its States’ progress towards the SDGs for 2030, culminating in the development of the first SDG India Index - Baseline Report 2018

Africa

Countries in Africa such as Ethiopia, Angola and South Africa worked with UN Country Teams and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to provide support to create awareness about SDGs among government officers, private sector workers, MPs and the civil society.

In Cape Verde, the government received support from the UNDP to convene an international conference on SDGs in June 2015. This contributed to the worldly discussions on the specific needs of Small Island Developing States in the view of the new global agenda on sustainable development. In the UN country team context, the government received support from UNDP to develop a roadmap (a plan) to place SDGs at the middle of its national development planning processes.

In Liberia, the government received support from UNDP to develop a roadmap to domesticate the AU Agenda 2063 and 2030 Agenda into the country's next national development plan. Outlines from the roadmap are steps to translate the Agenda 2063 and the SDGs into policies, plans and programs whiles considering the country is a Fragile State and applies the New Deal Principles.

Uganda was also claimed to be one of the first countries to develop its 2015/16-2019/20 national development plan in line with SDGs. It was estimated by its government that about 76% of the SDGs targets were reflected in the plan and was adapted to the national context. The UN Country Team was claimed to have supported the government to integrate the SDGs.

In Mauritania, the Ministry for the Economy and Finances received support from the UNDP to convene partners such as NGOs, government agencies, other ministries and the private sector in the discussion for implementing of the SDGs in the country, in the context of the UN Country Team. A national workshop was also supported by the UNDP to provide the methodology and tools for mainstreaming the SDGs into the country's new strategy.

The government of countries such as Togo, Sierra Leone, Madagascar and Uganda were claimed to have volunteered to conduct national reviews of their implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Support from UNDP was received to prepare their respective reports presented at the UN High-Level Political Forum. It was held during 11–20 July 2016 in New York in the United States. This forum was the UN global platform to review and follow up the SDGs and 2030 Agenda. It is said to provide guidance on policy to countries for implementing the goals.

Nigeria

Nigeria is one of the countries that presented its Voluntary National Review (VNR) in 2017 & 2020 on the implementation of the SDGs at the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF). In 2020, Nigeria ranked 160 on the 2020 world's SDG Index. The government affirmed that Nigeria's current development priorities and objectives are focused on achieving the SDGs. The Lagos SDGs Youth Alliance is another pivotal SDGs Initiative in Nigeria aimed at promoting the involvement of youth in achieving the 2030 Agenda and supporting long-term sustainable development strategy of Lagos state.

Ghana

Ghana aims to align its development priorities in partnership with CSOs and the private sector to achieve the SDGs in Ghana together.

Europe and Middle East

Baltic nations, via the Council of the Baltic Sea States, have created the Baltic 2030 Action Plan.

The World Pensions Forum has observed that the UK and European Union pension investors have been at the forefront of ESG-driven (Environmental, Social and Governance) asset allocation at home and abroad and early adopters of "SDG-centric" investment practices.

Iran

In December 2016 the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran held a special ceremony announcing a national education initiative that was arranged by the UNESCO office in Iran to implement the educational objectives of this global program. The announcement created a stir among politicians and Marja' in the country.

Lebanon

Lebanon adopted the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. It presented its first Voluntary National Review VNR in 2018 at the High Level Political Forum in New York. A national committee chaired by the Lebanese Prime Minister is leading the work on the SDGs in the country. In 2019, Lebanon's overall performance in the SDG Index ranked 6th out of 21 countries in the Arab region.

United Kingdom

The UK's approach to delivering the Global SDGs is outlined in Agenda 2030: Delivering the Global Goals, developed by the Department for International Development. In 2019, the Bond network analyzed the UK's global progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The Bond report highlights crucial gaps where attention and investment are most needed. The report was compiled by 49 organizations and 14 networks and working groups.

Americas

United States

193 governments including the United States ratified the SDGs. However, the UN reported minimal progress after three years within the 15-year timetable of this project. Funding remains trillions of dollars short. The United States stand last among the G20 nations to attain these Sustainable Development Goals and 36th worldwide.