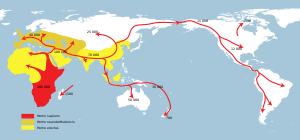

History of North America encompasses the past developments of people populating the continent of North America. While it was widely believed that continent first became a human habitat when people migrated across the Bering Sea 40,000 to 17,000 years ago, recent discoveries may have pushed those estimates back at least another 90,000 years. People settled throughout the continent, from the Inuit of the far north to the Mayans and Aztecs of the south. These complex communities each developed their own unique ways of life and cultures.

Records of European travel to North America begin with the Norse colonization in the tenth century AD. In 985, they founded a settlement on Greenland (an often-overlooked part of North America) that persisted until the early 1400s. They also explored the east coast of Canada, but their settlements there were much smaller and shorter-lived. With the Age of Exploration and the voyages of Christopher Columbus (starting 1492), Europeans began to arrive in the Americas in large numbers and to develop colonial ambitions for both North and South America. After Columbus, influxes of Europeans soon followed and overwhelmed the native population. North America became a staging ground for ongoing European rivalries. The continent was divided by three prominent European powers: England, France, and Spain. The influences of colonization by these states on North American cultures are still apparent today.

Conflict over resources on North America ensued in various wars between these powers, but, gradually, the new European colonies developed desires for independence. Revolutions, such as the American Revolution and Mexican War of Independence, created new, independent states that came to dominate North America. The Canadian Confederation formed in 1867, creating the modern political landscape of North America.

From the 19th to 21st centuries, North American states have developed increasingly deeper connections with each other. Although some conflicts have occurred, the continent has for the most part enjoyed peace and general cooperation between its states, as well as open commerce and trade between them. Modern developments include the opening of free trade agreements, extensive immigration from Mexico and Latin America, and drug trafficking concerns in these regions.

The beginning of North America

The specifics of Paleo-Indians' migration to and throughout the Americas, including the exact dates and routes traveled, are subject to ongoing research and discussion. For years, the traditional theory has been that these early migrants moved into the Beringia land bridge between eastern Siberia and present-day Alaska around 40,000–17,000 years ago, when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation. These people are believed to have followed herds of now-extinct pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets. Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific coast to South America. Evidence of the latter would since have been covered by a sea level rise of hundreds of meters following the last ice age.

Archaeologists contend that Paleo-Indian migration out of Beringia (eastern Alaska), ranges from 40,000 to around 16,500 years ago. This time range is a hot source of debate and promises to continue as such for years to come. The few agreements achieved to date are the origin from Central Asia, with widespread habitation of the Americas during the end of the last glacial period, or more specifically what is known as the late glacial maximum, around 16,000–13,000 years before present. However, older alternative theories exist, including migration from Europe.

Stone tools, particularly projectile points and scrapers, are the primary evidence of early human activity in the Americas. Crafted lithic flaked tools are used by archaeologists and anthropologists to classify cultural periods. Scientific evidence links indigenous Americans to Asian peoples, specifically eastern Siberian populations. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to North Asian populations by linguistic dialects, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA. 8,000–7,000 BCE (10,000–9,000 years ago) the climate stabilized, leading to a rise in population and lithic technology advances, resulting in a more sedentary lifestyle.

Pre-Columbian era

Before contact with Europeans, the indigenous peoples of North America were divided into many different polities, from small bands of a few families to large empires. They lived in numerous culture areas, which roughly correspond to geographic and biological zones. Societies adapted their subsistence strategies to their homelands, and some societies were hunter-gatherers, some horticulturists, some agriculturalists, and many a mix of these. Native groups can also be classified by their language family (e.g. Athapascan or Uto-Aztecan). It is important to note that people with similar languages did not always share the same material culture, nor were they always allies.

The Archaic period in the Americas saw a changing environment featuring a warmer more arid climate and the disappearance of the last megafauna. The majority of population groups at this time were still highly mobile hunter-gatherers; but now individual groups started to focus on resources available to them locally, thus with the passage of time there is a pattern of increasing regional generalization, for example the Southwest, Arctic, Poverty Point culture, Plains Arctic, Dalton, and Plano traditions. This kind of regional adaptation became the norm, with reliance less on hunting and gathering among many cultures, with a more mixed economy of small game, fish, seasonally wild vegetables and harvested plant foods. Many groups continued as big game hunters, but their hunting traditions became more varied, and meat procurement methods more sophisticated. The placement of artifacts and materials within an Archaic burial site indicated social differentiation based upon status in some groups.

Agriculture was invented independently in two regions of North America: the Eastern Woodlands and Mesoamerica. The more southern cultural groups of North America were responsible for the domestication of many common crops now used around the world, such as tomatoes and squash. Perhaps most importantly they domesticated one of the world's major staples, maize (corn). During the Plains Village period, agriculture and bison-hunting were important to Great Plains tribes.

As a result of the development of agriculture in the south, many important cultural advances were made there. For example, the Maya civilization developed a writing system, built huge pyramids, had a complex calendar, and developed the concept of zero 500 years before anyone in the Old World. The Mayan culture was still present when the Spanish arrived in Central America, but political dominance in the area had shifted to the Aztec Empire further north.

In the Southwest of North America, Hohokam and Ancestral Pueblo societies had been engaged in agricultural production with ditch irrigation and a sedentary village life for at least two millennia before the Spanish arrived in the 1540s. Upon the arrival of the Europeans in the "New World", native peoples found their culture changed drastically. As such, their affiliation with political and cultural groups changed as well, several linguistic groups went extinct, and others changed quite quickly. The name and cultures that Europeans recorded for the natives were not necessarily the same as the ones they had used a few generations before, or the ones in use today.

Arrival of Europeans

Early contact

There was limited contact between North American people and the outside world before 1492. Several theoretical contacts have been proposed, but the earliest physical evidence comes from the Norse or Vikings. Erik the Red founded a colony on Greenland in 985 CE. Erik's son Leif Eriksson is believed to have reached the Island of Newfoundland circa 1000, naming the discovery Vinland. The only Norse site outside of Greenland yet discovered in North America is at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada. All of the Norse colonies were eventually abandoned.

The Norse voyages did not become common knowledge in the Old World. Even the permanent settlement in Greenland, which persisted until the early 1400s, received little attention and Europeans remained largely ignorant of the existence of the Americas until 1492. As part of a general age of discovery, Italian sailor Christopher Columbus proposed a voyage west from Europe to find a shorter route to Asia. He eventually received the backing of Isabella I and Ferdinand II, Queen and King of newly united Spain. In 1492 Columbus reached land in the Bahamas.

Almost 500 years after the Norse, John Cabot explored the east coast of what would become Canada in 1497. Giovanni da Verrazzano explored the East Coast of North America from Florida to presumably Newfoundland in 1524. Jacques Cartier made a series of voyages on behalf of the French crown in 1534 and explored the St. Lawrence River.

Successful colonization

To understand what constitutes successful colonization, it is important to understand what colonization means. Colonization refers to large-scale population movements in which the migrants maintain strong links with their or their ancestors' former country, gaining significant advantages over other inhabitants of the territory by such links. When colonization takes place under the protection of clearly colonial political structures, it may most handily be called settler colonialism. This often involves the settlers' entirely dispossessing earlier inhabitants, or instituting legal and other structures which systematically disadvantage them.

Initially, European activity consisted mostly of trade and exploration. Eventually Europeans began to establish settlements. The three principal colonial powers in North America were Spain, England, and France, although eventually other powers such as the Netherlands and Sweden also received holdings on the continent.

Settlement by the Spanish started the European colonization of the Americas. They gained control of most of the largest islands in the Caribbean and conquered the Aztec empire, gaining control of present-day Mexico and Central America. This was the beginning of the Spanish Empire in the New World. The first successful Spanish settlement in continental North America was Veracruz founded by Hernán Cortés in 1519, followed by many other settlements in colonial New Spain, including Spanish Florida, Central America, New Mexico, and later California. The Spanish claimed all of North and South America (with the exception of Brazil), and no other European power challenged those claims by planting colonies until over a century after Spain's first settlements.

The first French settlements were Port Royal (1604) and Quebec City (1608) in what is now Nova Scotia and Quebec. The Fur Trade soon became the primary business on the continent and as a result transformed the indigenous North American ways of life.

The first permanent English settlements were at Jamestown (1607) (along with its satellite, Bermuda in 1609) and Plymouth (1620), in what are today Virginia and Massachusetts respectively. Further to the south, plantation slavery became the main industry of the West Indies, and this gave rise to the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade.

Colonial era

in the interactive SVG version on a compatible browser, hover over the timeline to step through time

By the year 1663 the French crown had taken over control of New France from the fur-trading companies, and the English charter colonies gave way to more metropolitan control. This ushered in a new era of more formalized colonialism in North America.

Rivalry between the European powers created a series of wars on the North American landmass that would have great impact on the development of the colonies. Territory often changed hands multiple times. Peace was not achieved until French forces in North America were vanquished at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham at Quebec City, and France ceded most of her claims outside of the Caribbean. The end of the French presence in North America was a disaster for most Native nations in Eastern North America, who lost their major ally against the expanding Anglo-American settlement's. During Pontiac's Rebellion from 1763 to 1766, a confederation of Great Lakes-area tribes fought a somewhat successful campaign to defend their rights over their lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, which had been "reserved" for them under the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

Viceroyalty of New Spain (present-day Mexico) was the name of the viceroy-ruled territories of the Spanish Empire in Asia, North America and its peripheries from 1535 to 1821.

Revolutions

The coming of the American Revolution had a great impact across the continent. Most importantly it directly led to the creation of the United States of America. However, the associated American Revolutionary War was an important war that touched all corners of the region. The flight of the United Empire Loyalists led to the creation of English Canada as a separate community

Meanwhile, Spain's hold on Mexico was weakening. Independence was declared in 1810 by Miguel Hidalgo, starting the Mexican War of Independence. In 1813, José María Morelos and the Congress of Anáhuac signed the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America, the first legal document where the separation of the New Spain with respect to Spain is proclaimed. Spain finally recognized Mexico's independence in 1821.

Expansion era

From the time of independence of the United States, that country expanded rapidly to the west, acquiring the massive Louisiana territory in 1803. Between 1810 and 1811 a Native confederacy under Tecumseh fought unsuccessfully to keep the Americans from pushing them out of the Great Lakes. Tecumseh's followers then went north into Canada, where they helped the British to block an American attempt to seize Canada during the War of 1812. Following the war, British and Irish settlement in Canada increased dramatically.

US expansion was complicated by the division between "free" and "slave" states, which led to the Missouri Compromise in 1820. Likewise, Canada faced a division between French and English communities that led to the outbreak of civil strife in 1837. Mexico faced constant political tensions between liberals and conservatives, as well as the rebellion of the English-speaking region of Texas, which declared itself the Republic of Texas in 1836. In 1845 Texas joined the United States, which would later lead to the Mexican–American War in 1846 that began American imperialism. As a result of conflict with Mexico, the United States made further territorial gains in California and the Southwest.

Conflict, confederation, and invasion

The secession of the Confederate States and the resulting civil war rocked American society. It eventually led to the end of slavery in the United States, the destruction and later reconstruction of most of the South, and tremendous loss of life. From the conflict, the United States emerged as a powerful industrialized nation.

Partly as a response to the threat of American power, four of the Canadian colonies agreed to federate in 1867, creating the Dominion of Canada. The new nation was not fully sovereign, but enjoyed considerable independence from Britain. With the addition of British Columbia Canada would expand to the Pacific by 1871 and establish a transcontinental railway, the Canadian Pacific, by 1885.

In Mexico conflicts like the Reform War left the state weak, and open to foreign influence. This led to the Second French Empire to invade Mexico.

Late 19th century

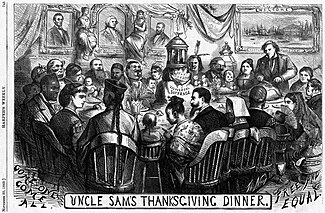

In both the United States and Canada, the second half of the 19th century witnessed massive inflows of immigration to settle the West. These lands were not uninhabited however: in the United States the government fought numerous Indian Wars against the native inhabitants. In Canada, relations were more peaceful, as a result of the Numbered Treaties, but two rebellions broke out in 1870 and 1885 on the prairies. The British colony of Newfoundland became a dominion in 1907.

In Mexico, the entire era was dominated by the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz.

World Wars era

World War I

As a part of the British Empire Canada immediately was at war in 1914. Canada bore the brunt of several major battles during the early stages of the war including the use of poison gas attacks at Ypres. Losses became grave, and the government eventually brought in conscription, despite the fact this was against the wishes of the majority of French Canadians. In the ensuing Conscription Crisis of 1917, riots broke out on the streets of Montreal. In neighboring Newfoundland, the new dominion suffered a devastating loss on July 1, 1916, the First day on the Somme.

The United States stayed apart from the conflict until 1917, joining the Entente powers. The United States was then able to play a crucial role at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 that shaped interwar Europe.

Mexico was not part of the war as the country was embroiled in the Mexican Revolution at the time.

Interwar years

The 1920s brought an age of great prosperity in the United States, and to a lesser degree Canada. But the Wall Street Crash of 1929 combined with drought ushered in a period of economic hardship in the United States and Canada.

From 1937 to 1949, this was a popular uprising against the anti-Catholic Mexican government of the time, set off specifically by the anti-clerical provisions of the Mexican Constitution of 1917.

World War II

Once again Canada found itself at war before her neighbors, however even Canadian contributions were slight before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The entry of the United States into the war helped to tip the balance in favor of the Allies. On August 19, 1942, a force of some 6000, largely Canadian, infantry was landed near the French channel port of Dieppe. The German defenders under General von Rundstedt destroyed the invaders. 907 Canadians were killed and almost 2,500 captured (many wounded). Lessons learned in this abortive raid were put to good use 2 years later in the successful Normandy invasion.

Two Mexican tankers, transporting oil to the United States, were attacked and sunk by the Germans in the Gulf of Mexico waters, in 1942. The incident happened in spite of Mexico's neutrality at that time. This led Mexico to declare war on the Axis nations and enter the conflict.

The destruction of Europe wrought by the war vaulted all North American countries to more important roles in world affairs. The United States especially emerged as a "superpower".

Post-war

The early Cold War era saw the United States as the most powerful nation in a Western coalition of which Mexico and Canada were also a part. At home, the United States witnessed convulsive change especially in the area of race relations. In Canada this was mirrored by the Quiet Revolution and the emergence of Quebec nationalism.

Mexico experienced an era of huge economic growth after World War II, a heavy industrialization process and a growth of its middle class, a period known in Mexican history as the "El Milagro Mexicano" (Mexican miracle).

The Caribbean saw the beginnings of decolonization, while on the largest island the Cuban Revolution introduced Cold War rivalries into Latin America.

In 1959 the non-contiguous US territories of Alaska and Hawaii became US states.

Vietnam War and stagflation

During this time the United States became involved in the Vietnam War as part of the global Cold War. This war would later prove to be highly divisive in American society, and American troops were withdrawn from Indochina in 1975 with the Khmer Rouge's capture of Phnom Penh on April 17, the Vietnam People's Army's capture of Saigon on April 30 and the Pathet Lao's capture of Vientiane on December 2.

Canada during this era was dominated by the leadership of Pierre Elliot Trudeau. Eventually in 1982 at the end of his tenure, Canada received a new constitution.

Both the United States and Canada experienced stagflation, which eventually led to a revival in small-government politics.

The 1980s

Mexican presidents Miguel de la Madrid, in the early 1980s and Carlos Salinas de Gortari in the late 1980s, started implementing liberal economic strategies that were seen as a good move. However, Mexico experienced a strong economic recession in 1982 and the Mexican peso suffered a devaluation. Presidential elections held in 1988 were forecast to be very competitive and they were. Leftist candidate Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, son of Lázaro Cárdenas one of the most beloved Mexican presidents, created a successful campaign and was reported as the leader in several opinion polls. On July 6, 1988, the day of the elections, a system shutdown of the IBM AS/400 that the government was using to count the votes occurred, presumably by accident. The government simply stated that "se cayó el sistema" ("the system crashed"), to refer to the incident. When the system was finally restored, the PRI candidate Carlos Salinas was declared the official winner. It was the first time since the Revolution that a non-PRI candidate was so close to winning the presidency.

In the United States president Ronald Reagan attempted to move the United States back towards a hard anti-communist line in foreign affairs, in what his supporters saw as an attempt to assert moral leadership (compared to the Soviet Union) in the world community. Domestically, Reagan attempted to bring in a package of privatization and trickle down economics to stimulate the economy.

Canada's Brian Mulroney ran on a similar platform to Reagan, and also favored closer trade ties with the United States. This led to the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement in January 1989.

Recent history

The End of the Cold War and the beginning of the era of sustained economic expansion coincided during the 1990s. On January 1, 1994, Canada, Mexico, and the United States signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, creating the world's largest free trade area. Quebec held a referendum in 1995 for national sovereignty in which 51% voted no to 49% yes. In 2000, Vicente Fox became the first non-PRI candidate to win the Mexican presidency in over 70 years.

The optimism of the 1990s was shattered by the 9/11 attacks of 2001 on the United States, which prompted the 20-year period of military intervention war in Afghanistan, which Canada also participated in. Meanwhile, Canada and Mexico both did not support the United States later moves to invade Iraq.

In 2006, the drug war in Mexico evolved into an actual military conflict with each year more deadly than the last.

Starting in early 2008, the Great Recession in 3 North American nations began, which eventually triggered a worldwide recession in the Fall of 2008 and still has not recovered until 2009. In 2009, Barack Obama was inaugurated as the first African American to be President of the United States. 2 years later, Osama Bin Laden, the perpetrator of 9/11, was found and killed. On December 18, 2011, the Iraq War was declared formally over once the troops had pulled out.

In 2016, Donald Trump was elected 45th President, who defeated Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, and in 2017, he was sworn in as president. In early 2020, the United States confirmed the first case of the novel coronavirus, and later that month in March, North America went into national lockdown as the whole region was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. As of December 2021, three North American nations have suffered more than 1.3 million COVID-19 related deaths.

In 2020, Joe Biden was elected 46th President, who defeated Donald Trump in 2020 presidential election, although Trump refused to concede the election, and on January 6, 2021, a group of his supporters stormed the United States Capitol in an unsuccessful effort to disrupt the presidential Electoral College vote count.

Also, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called a snap election in 2021 to try and increase the Liberals seat share and reach a majority government. The results of 2021 federal election were mostly unchanged from 2019 federal election, with the Liberals forming another minority government.