Classical conditioning (also known as Pavlovian or respondent conditioning) is a behavioral procedure in which a biologically potent stimulus (e.g. food) is paired with a previously neutral stimulus (e.g. a triangle). It also refers to the learning process that results from this pairing, through which the neutral stimulus comes to elicit a response (e.g. salivation) that is usually similar to the one elicited by the potent stimulus.

Classical conditioning is distinct from operant conditioning (also called instrumental conditioning), through which the strength of a voluntary behavior is modified by reinforcement or punishment. However, classical conditioning can affect operant conditioning in various ways; notably, classically conditioned stimuli may serve to reinforce operant responses.

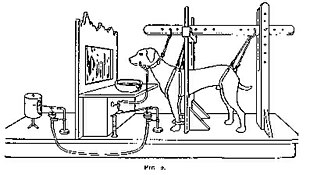

Classical conditioning was first studied in detail by Ivan Pavlov, who conducted experiments with dogs and published his findings in 1897. During the Russian physiologist's study of digestion, Pavlov observed that the dogs serving as his subjects drooled when they were being served meat.

Classical conditioning is a basic behavioral mechanism, and its neural substrates are now beginning to be understood. Though it is sometimes hard to distinguish classical conditioning from other forms of associative learning (e.g. instrumental learning and human associative memory), a number of observations differentiate them, especially the contingencies whereby learning occurs.

Together with operant conditioning, classical conditioning became the foundation of behaviorism, a school of psychology which was dominant in the mid-20th century and is still an important influence on the practice of psychological therapy and the study of animal behavior. Classical conditioning has been applied in other areas as well. For example, it may affect the body's response to psychoactive drugs, the regulation of hunger, research on the neural basis of learning and memory, and in certain social phenomena such as the false consensus effect.

Definition

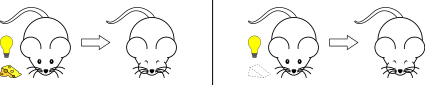

Classical conditioning occurs when a conditioned stimulus (CS) is paired with an unconditioned stimulus (US). Usually, the conditioned stimulus is a neutral stimulus (e.g., the sound of a tuning fork), the unconditioned stimulus is biologically potent (e.g., the taste of food) and the unconditioned response (UR) to the unconditioned stimulus is an unlearned reflex response (e.g., salivation). After pairing is repeated the organism exhibits a conditioned response (CR) to the conditioned stimulus when the conditioned stimulus is presented alone. (A conditioned response may occur after only one pairing.) Thus, unlike the UR, the CR is acquired through experience, and it is also less permanent than the UR.

Usually the conditioned response is similar to the unconditioned response, but sometimes it is quite different. For this and other reasons, most learning theorists suggest that the conditioned stimulus comes to signal or predict the unconditioned stimulus, and go on to analyze the consequences of this signal. Robert A. Rescorla provided a clear summary of this change in thinking, and its implications, in his 1988 article "Pavlovian conditioning: It's not what you think it is". Despite its widespread acceptance, Rescorla's thesis may not be defensible.

Classical conditioning differs from operant or instrumental conditioning: in classical conditioning, behaviors are modified through the association of stimuli as described above, whereas in operant conditioning behaviors are modified by the effect they produce (i.e., reward or punishment).

Procedures

Pavlov's research

The best-known and most thorough early work on classical conditioning was done by Ivan Pavlov, although Edwin Twitmyer published some related findings a year earlier. During his research on the physiology of digestion in dogs, Pavlov developed a procedure that enabled him to study the digestive processes of animals over long periods of time. He redirected the animal's digestive fluids outside the body, where they could be measured. Pavlov noticed that his dogs began to salivate in the presence of the technician who normally fed them, rather than simply salivating in the presence of food. Pavlov called the dogs' anticipatory salivation "psychic secretion". Putting these informal observations to an experimental test, Pavlov presented a stimulus (e.g. the sound of a metronome) and then gave the dog food; after a few repetitions, the dogs started to salivate in response to the stimulus. Pavlov concluded that if a particular stimulus in the dog's surroundings was present when the dog was given food then that stimulus could become associated with food and cause salivation on its own.

Terminology

In Pavlov's experiments the unconditioned stimulus (US) was the food because its effects did not depend on previous experience. The metronome's sound is originally a neutral stimulus (NS) because it does not elicit salivation in the dogs. After conditioning, the metronome's sound becomes the conditioned stimulus (CS) or conditional stimulus; because its effects depend on its association with food. Likewise, the responses of the dog follow the same conditioned-versus-unconditioned arrangement. The conditioned response (CR) is the response to the conditioned stimulus, whereas the unconditioned response (UR) corresponds to the unconditioned stimulus.

Pavlov reported many basic facts about conditioning; for example, he found that learning occurred most rapidly when the interval between the CS and the appearance of the US was relatively short.

As noted earlier, it is often thought that the conditioned response is a replica of the unconditioned response, but Pavlov noted that saliva produced by the CS differs in composition from that produced by the US. In fact, the CR may be any new response to the previously neutral CS that can be clearly linked to experience with the conditional relationship of CS and US. It was also thought that repeated pairings are necessary for conditioning to emerge, but many CRs can be learned with a single trial, especially in fear conditioning and taste aversion learning.

Forward conditioning

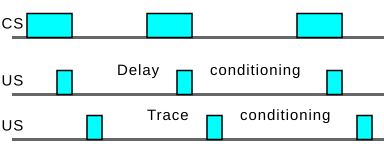

Learning is fastest in forward conditioning. During forward conditioning, the onset of the CS precedes the onset of the US in order to signal that the US will follow. Two common forms of forward conditioning are delay and trace conditioning.

- Delay conditioning: In delay conditioning, the CS is presented and is overlapped by the presentation of the US. For example, if a person hears a buzzer for five seconds, during which time air is puffed into their eye, the person will blink. After several pairings of the buzzer and the puff, the person will blink at the sound of the buzzer alone. This is delay conditioning.

- Trace conditioning: During trace conditioning, the CS and US do not overlap. Instead, the CS begins and ends before the US is presented. The stimulus-free period is called the trace interval or the conditioning interval. If in the above buzzer example, the puff came a second after the sound of the buzzer stopped, that would be trace conditioning, with a trace or conditioning interval of one second.

Simultaneous conditioning

During simultaneous conditioning, the CS and US are presented and terminated at the same time. For example: If a person hears a bell and has air puffed into their eye at the same time, and repeated pairings like this led to the person blinking when they hear the bell despite the puff of air being absent, this demonstrates that simultaneous conditioning has occurred.

Second-order and higher-order conditioning

Second-order or higher-order conditioning follow a two-step procedure. First a neutral stimulus ("CS1") comes to signal a US through forward conditioning. Then a second neutral stimulus ("CS2") is paired with the first (CS1) and comes to yield its own conditioned response. For example: A bell might be paired with food until the bell elicits salivation. If a light is then paired with the bell, then the light may come to elicit salivation as well. The bell is the CS1 and the food is the US. The light becomes the CS2 once it is paired with the CS1.

Backward conditioning

Backward conditioning occurs when a CS immediately follows a US. Unlike the usual conditioning procedure, in which the CS precedes the US, the conditioned response given to the CS tends to be inhibitory. This presumably happens because the CS serves as a signal that the US has ended, rather than as a signal that the US is about to appear. For example, a puff of air directed at a person's eye could be followed by the sound of a buzzer.

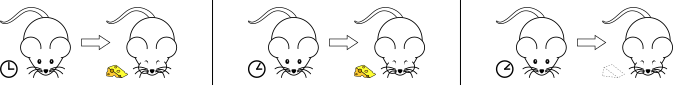

Temporal conditioning

In temporal conditioning, a US is presented at regular intervals, for instance every 10 minutes. Conditioning is said to have occurred when the CR tends to occur shortly before each US. This suggests that animals have a biological clock that can serve as a CS. This method has also been used to study timing ability in animals (see Animal cognition).

The example below shows the temporal conditioning, as US such as food to a hungry mouse is simply delivered on a regular time schedule such as every thirty seconds. After sufficient exposure the mouse will begin to salivate just before the food delivery. This then makes it temporal conditioning as it would appear that the mouse is conditioned to the passage of time.

Zero contingency procedure

In this procedure, the CS is paired with the US, but the US also occurs at other times. If this occurs, it is predicted that the US is likely to happen in the absence of the CS. In other words, the CS does not "predict" the US. In this case, conditioning fails and the CS does not come to elicit a CR. This finding – that prediction rather than CS-US pairing is the key to conditioning – greatly influenced subsequent conditioning research and theory.

Extinction

In the extinction procedure, the CS is presented repeatedly in the absence of a US. This is done after a CS has been conditioned by one of the methods above. When this is done, the CR frequency eventually returns to pre-training levels. However, extinction does not eliminate the effects of the prior conditioning. This is demonstrated by spontaneous recovery – when there is a sudden appearance of the (CR) after extinction occurs – and other related phenomena (see "Recovery from extinction" below). These phenomena can be explained by postulating accumulation of inhibition when a weak stimulus is presented.

Phenomena observed

Acquisition

During acquisition, the CS and US are paired as described above. The extent of conditioning may be tracked by test trials. In these test trials, the CS is presented alone and the CR is measured. A single CS-US pairing may suffice to yield a CR on a test, but usually a number of pairings are necessary and there is a gradual increase in the conditioned response to the CS. This repeated number of trials increase the strength and/or frequency of the CR gradually. The speed of conditioning depends on a number of factors, such as the nature and strength of both the CS and the US, previous experience and the animal's motivational state. The process slows down as it nears completion.

Extinction

If the CS is presented without the US, and this process is repeated often enough, the CS will eventually stop eliciting a CR. At this point the CR is said to be "extinguished."

External inhibition

External inhibition may be observed if a strong or unfamiliar stimulus is presented just before, or at the same time as, the CS. This causes a reduction in the conditioned response to the CS.

Recovery from extinction

Several procedures lead to the recovery of a CR that had been first conditioned and then extinguished. This illustrates that the extinction procedure does not eliminate the effect of conditioning. These procedures are the following:

- Reacquisition: If the CS is again paired with the US, a CR is again acquired, but this second acquisition usually happens much faster than the first one.

- Spontaneous recovery: Spontaneous recovery is defined as the reappearance of a previously extinguished conditioned response after a rest period. That is, if the CS is tested at a later time (for example an hour or a day) after extinction it will again elicit a CR. This renewed CR is usually much weaker than the CR observed prior to extinction.

- Disinhibition: If the CS is tested just after extinction and an intense but associatively neutral stimulus has occurred, there may be a temporary recovery of the conditioned response to the CS.

- Reinstatement: If the US used in conditioning is presented to a subject in the same place where conditioning and extinction occurred, but without the CS being present, the CS often elicits a response when it is tested later.

- Renewal: Renewal is a reemergence of a conditioned response following extinction when an animal is returned to the environment *(or similar environment) in which the conditioned response was acquired.

Stimulus generalization

Stimulus generalization is said to occur if, after a particular CS has come to elicit a CR, a similar test stimulus is found to elicit the same CR. Usually the more similar the test stimulus is to the CS the stronger the CR will be to the test stimulus. Conversely, the more the test stimulus differs from the CS, the weaker the CR will be, or the more it will differ from that previously observed.

Stimulus discrimination

One observes stimulus discrimination when one stimulus ("CS1") elicits one CR and another stimulus ("CS2") elicits either another CR or no CR at all. This can be brought about by, for example, pairing CS1 with an effective US and presenting CS2 with no US.

Latent inhibition

Latent inhibition refers to the observation that it takes longer for a familiar stimulus to become a CS than it does for a novel stimulus to become a CS, when the stimulus is paired with an effective US.

Conditioned suppression

This is one of the most common ways to measure the strength of learning in classical conditioning. A typical example of this procedure is as follows: a rat first learns to press a lever through operant conditioning. Then, in a series of trials, the rat is exposed to a CS, a light or a noise, followed by the US, a mild electric shock. An association between the CS and US develops, and the rat slows or stops its lever pressing when the CS comes on. The rate of pressing during the CS measures the strength of classical conditioning; that is, the slower the rat presses, the stronger the association of the CS and the US. (Slow pressing indicates a "fear" conditioned response, and it is an example of a conditioned emotional response; see section below.)

Conditioned inhibition

Typically, three phases of conditioning are used.

Phase 1

A CS (CS+) is paired with a US until asymptotic CR levels are reached.

Phase 2

CS+/US trials are continued, but these are interspersed with trials on which the CS+ is paired with a second CS, (the CS-) but not with the US (i.e. CS+/CS- trials). Typically, organisms show CRs on CS+/US trials, but stop responding on CS+/CS− trials.

Phase 3

- Summation test for conditioned inhibition: The CS- from phase 2 is presented together with a new CS+ that was conditioned as in phase 1. Conditioned inhibition is found if the response is less to the CS+/CS- pair than it is to the CS+ alone.

- Retardation test for conditioned inhibition: The CS- from phase 2 is paired with the US. If conditioned inhibition has occurred, the rate of acquisition to the previous CS− should be less than the rate of acquisition that would be found without the phase 2 treatment.

Blocking

This form of classical conditioning involves two phases.

Phase 1

A CS (CS1) is paired with a US.

Phase 2

A compound CS (CS1+CS2) is paired with a US.

Test

A separate test for each CS (CS1 and CS2) is performed. The blocking effect is observed in a lack of conditional response to CS2, suggesting that the first phase of training blocked the acquisition of the second CS.

Theories

Data sources

Experiments on theoretical issues in conditioning have mostly been done on vertebrates, especially rats and pigeons. However, conditioning has also been studied in invertebrates, and very important data on the neural basis of conditioning has come from experiments on the sea slug, Aplysia. Most relevant experiments have used the classical conditioning procedure, although instrumental (operant) conditioning experiments have also been used, and the strength of classical conditioning is often measured through its operant effects, as in conditioned suppression (see Phenomena section above) and autoshaping.

Stimulus-substitution theory

According to Pavlov, conditioning does not involve the acquisition of any new behavior, but rather the tendency to respond in old ways to new stimuli. Thus, he theorized that the CS merely substitutes for the US in evoking the reflex response. This explanation is called the stimulus-substitution theory of conditioning. A critical problem with the stimulus-substitution theory is that the CR and UR are not always the same. Pavlov himself observed that a dog's saliva produced as a CR differed in composition from that produced as a UR. The CR is sometimes even the opposite of the UR. For example: the unconditional response to electric shock is an increase in heart rate, whereas a CS that has been paired with the electric shock elicits a decrease in heart rate. (However, it has been proposed that only when the UR does not involve the central nervous system are the CR and the UR opposites.)

Rescorla–Wagner model

The Rescorla–Wagner (R–W) model is a relatively simple yet powerful model of conditioning. The model predicts a number of important phenomena, but it also fails in important ways, thus leading to a number of modifications and alternative models. However, because much of the theoretical research on conditioning in the past 40 years has been instigated by this model or reactions to it, the R–W model deserves a brief description here.

The Rescorla-Wagner model argues that there is a limit to the amount of conditioning that can occur in the pairing of two stimuli. One determinant of this limit is the nature of the US. For example: pairing a bell with a juicy steak is more likely to produce salivation than pairing the bell with a piece of dry bread, and dry bread is likely to work better than a piece of cardboard. A key idea behind the R–W model is that a CS signals or predicts the US. One might say that before conditioning, the subject is surprised by the US. However, after conditioning, the subject is no longer surprised, because the CS predicts the coming of the US. (Note that the model can be described mathematically and that words like predict, surprise, and expect are only used to help explain the model.) Here the workings of the model are illustrated with brief accounts of acquisition, extinction, and blocking. The model also predicts a number of other phenomena, see main article on the model.

Equation

This is the Rescorla-Wagner equation. It specifies the amount of learning that will occur on a single pairing of a conditioning stimulus (CS) with an unconditioned stimulus (US). The above equation is solved repeatedly to predict the course of learning over many such trials.

In this model the degree of learning is measured by how well the CS predicts the US, which is given by the "associative strength" of the CS. In the equation, V represents the current associative strength of the CS, and ∆V is the change in this strength that happens on a given trial. ΣV is the sum of the strengths of all stimuli present in the situation. λ is the maximum associative strength that a given US will support; its value is usually set to 1 on trials when the US is present, and 0 when the US is absent. α and β are constants related to the salience of the CS and the speed of learning for a given US. How the equation predicts various experimental results is explained in following sections. For further details, see the main article on the model.

R–W model: acquisition

The R–W model measures conditioning by assigning an "associative strength" to the CS and other local stimuli. Before a CS is conditioned it has an associative strength of zero. Pairing the CS and the US causes a gradual increase in the associative strength of the CS. This increase is determined by the nature of the US (e.g. its intensity). The amount of learning that happens during any single CS-US pairing depends on the difference between the total associative strengths of CS and other stimuli present in the situation (ΣV in the equation), and a maximum set by the US (λ in the equation). On the first pairing of the CS and US, this difference is large and the associative strength of the CS takes a big step up. As CS-US pairings accumulate, the US becomes more predictable, and the increase in associative strength on each trial becomes smaller and smaller. Finally, the difference between the associative strength of the CS (plus any that may accrue to other stimuli) and the maximum strength reaches zero. That is, the US is fully predicted, the associative strength of the CS stops growing, and conditioning is complete.

R–W model: extinction

The associative process described by the R–W model also accounts for extinction (see "procedures" above). The extinction procedure starts with a positive associative strength of the CS, which means that the CS predicts that the US will occur. On an extinction trial the US fails to occur after the CS. As a result of this "surprising" outcome, the associative strength of the CS takes a step down. Extinction is complete when the strength of the CS reaches zero; no US is predicted, and no US occurs. However, if that same CS is presented without the US but accompanied by a well-established conditioned inhibitor (CI), that is, a stimulus that predicts the absence of a US (in R-W terms, a stimulus with a negative associate strength) then R-W predicts that the CS will not undergo extinction (its V will not decrease in size).

R–W model: blocking

The most important and novel contribution of the R–W model is its assumption that the conditioning of a CS depends not just on that CS alone, and its relationship to the US, but also on all other stimuli present in the conditioning situation. In particular, the model states that the US is predicted by the sum of the associative strengths of all stimuli present in the conditioning situation. Learning is controlled by the difference between this total associative strength and the strength supported by the US. When this sum of strengths reaches a maximum set by the US, conditioning ends as just described.

The R–W explanation of the blocking phenomenon illustrates one consequence of the assumption just stated. In blocking (see "phenomena" above), CS1 is paired with a US until conditioning is complete. Then on additional conditioning trials a second stimulus (CS2) appears together with CS1, and both are followed by the US. Finally CS2 is tested and shown to produce no response because learning about CS2 was "blocked" by the initial learning about CS1. The R–W model explains this by saying that after the initial conditioning, CS1 fully predicts the US. Since there is no difference between what is predicted and what happens, no new learning happens on the additional trials with CS1+CS2, hence CS2 later yields no response.

Theoretical issues and alternatives to the Rescorla–Wagner model

One of the main reasons for the importance of the R–W model is that it is relatively simple and makes clear predictions. Tests of these predictions have led to a number of important new findings and a considerably increased understanding of conditioning. Some new information has supported the theory, but much has not, and it is generally agreed that the theory is, at best, too simple. However, no single model seems to account for all the phenomena that experiments have produced. Following are brief summaries of some related theoretical issues.

Content of learning

The R–W model reduces conditioning to the association of a CS and US, and measures this with a single number, the associative strength of the CS. A number of experimental findings indicate that more is learned than this. Among these are two phenomena described earlier in this article

- Latent inhibition: If a subject is repeatedly exposed to the CS before conditioning starts, then conditioning takes longer. The R–W model cannot explain this because preexposure leaves the strength of the CS unchanged at zero.

- Recovery of responding after extinction: It appears that something remains after extinction has reduced associative strength to zero because several procedures cause responding to reappear without further conditioning.

Role of attention in learning

Latent inhibition might happen because a subject stops focusing on a CS that is seen frequently before it is paired with a US. In fact, changes in attention to the CS are at the heart of two prominent theories that try to cope with experimental results that give the R–W model difficulty. In one of these, proposed by Nicholas Mackintosh, the speed of conditioning depends on the amount of attention devoted to the CS, and this amount of attention depends in turn on how well the CS predicts the US. Pearce and Hall proposed a related model based on a different attentional principle Both models have been extensively tested, and neither explains all the experimental results. Consequently, various authors have attempted hybrid models that combine the two attentional processes. Pearce and Hall in 2010 integrated their attentional ideas and even suggested the possibility of incorporating the Rescorla-Wagner equation into an integrated model.

Context

As stated earlier, a key idea in conditioning is that the CS signals or predicts the US (see "zero contingency procedure" above). However, for example, the room in which conditioning takes place also "predicts" that the US may occur. Still, the room predicts with much less certainty than does the experimental CS itself, because the room is also there between experimental trials, when the US is absent. The role of such context is illustrated by the fact that the dogs in Pavlov's experiment would sometimes start salivating as they approached the experimental apparatus, before they saw or heard any CS. Such so-called "context" stimuli are always present, and their influence helps to account for some otherwise puzzling experimental findings. The associative strength of context stimuli can be entered into the Rescorla-Wagner equation, and they play an important role in the comparator and computational theories outlined below.

Comparator theory

To find out what has been learned, we must somehow measure behavior ("performance") in a test situation. However, as students know all too well, performance in a test situation is not always a good measure of what has been learned. As for conditioning, there is evidence that subjects in a blocking experiment do learn something about the "blocked" CS, but fail to show this learning because of the way that they are usually tested.

"Comparator" theories of conditioning are "performance based", that is, they stress what is going on at the time of the test. In particular, they look at all the stimuli that are present during testing and at how the associations acquired by these stimuli may interact. To oversimplify somewhat, comparator theories assume that during conditioning the subject acquires both CS-US and context-US associations. At the time of the test, these associations are compared, and a response to the CS occurs only if the CS-US association is stronger than the context-US association. After a CS and US are repeatedly paired in simple acquisition, the CS-US association is strong and the context-US association is relatively weak. This means that the CS elicits a strong CR. In "zero contingency" (see above), the conditioned response is weak or absent because the context-US association is about as strong as the CS-US association. Blocking and other more subtle phenomena can also be explained by comparator theories, though, again, they cannot explain everything.

Computational theory

An organism's need to predict future events is central to modern theories of conditioning. Most theories use associations between stimuli to take care of these predictions. For example: In the R–W model, the associative strength of a CS tells us how strongly that CS predicts a US. A different approach to prediction is suggested by models such as that proposed by Gallistel & Gibbon (2000, 2002). Here the response is not determined by associative strengths. Instead, the organism records the times of onset and offset of CSs and USs and uses these to calculate the probability that the US will follow the CS. A number of experiments have shown that humans and animals can learn to time events (see Animal cognition), and the Gallistel & Gibbon model yields very good quantitative fits to a variety of experimental data. However, recent studies have suggested that duration-based models cannot account for some empirical findings as well as associative models.

Element-based models

The Rescorla-Wagner model treats a stimulus as a single entity, and it represents the associative strength of a stimulus with one number, with no record of how that number was reached. As noted above, this makes it hard for the model to account for a number of experimental results. More flexibility is provided by assuming that a stimulus is internally represented by a collection of elements, each of which may change from one associative state to another. For example, the similarity of one stimulus to another may be represented by saying that the two stimuli share elements in common. These shared elements help to account for stimulus generalization and other phenomena that may depend upon generalization. Also, different elements within the same set may have different associations, and their activations and associations may change at different times and at different rates. This allows element-based models to handle some otherwise inexplicable results.

The SOP model

A prominent example of the element approach is the "SOP" model of Wagner. The model has been elaborated in various ways since its introduction, and it can now account in principle for a very wide variety of experimental findings. The model represents any given stimulus with a large collection of elements. The time of presentation of various stimuli, the state of their elements, and the interactions between the elements, all determine the course of associative processes and the behaviors observed during conditioning experiments.

The SOP account of simple conditioning exemplifies some essentials of the SOP model. To begin with, the model assumes that the CS and US are each represented by a large group of elements. Each of these stimulus elements can be in one of three states:

- primary activity (A1) - Roughly speaking, the stimulus is "attended to." (References to "attention" are intended only to aid understanding and are not part of the model.)

- secondary activity (A2) - The stimulus is "peripherally attended to."

- inactive (I) – The stimulus is "not attended to."

Of the elements that represent a single stimulus at a given moment, some may be in state A1, some in state A2, and some in state I.

When a stimulus first appears, some of its elements jump from inactivity I to primary activity A1. From the A1 state they gradually decay to A2, and finally back to I. Element activity can only change in this way; in particular, elements in A2 cannot go directly back to A1. If the elements of both the CS and the US are in the A1 state at the same time, an association is learned between the two stimuli. This means that if, at a later time, the CS is presented ahead of the US, and some CS elements enter A1, these elements will activate some US elements. However, US elements activated indirectly in this way only get boosted to the A2 state. (This can be thought of the CS arousing a memory of the US, which will not be as strong as the real thing.) With repeated CS-US trials, more and more elements are associated, and more and more US elements go to A2 when the CS comes on. This gradually leaves fewer and fewer US elements that can enter A1 when the US itself appears. In consequence, learning slows down and approaches a limit. One might say that the US is "fully predicted" or "not surprising" because almost all of its elements can only enter A2 when the CS comes on, leaving few to form new associations.

The model can explain the findings that are accounted for by the Rescorla-Wagner model and a number of additional findings as well. For example, unlike most other models, SOP takes time into account. The rise and decay of element activation enables the model to explain time-dependent effects such as the fact that conditioning is strongest when the CS comes just before the US, and that when the CS comes after the US ("backward conditioning") the result is often an inhibitory CS. Many other more subtle phenomena are explained as well.

A number of other powerful models have appeared in recent years which incorporate element representations. These often include the assumption that associations involve a network of connections between "nodes" that represent stimuli, responses, and perhaps one or more "hidden" layers of intermediate interconnections. Such models make contact with a current explosion of research on neural networks, artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Applications

Neural basis of learning and memory

Pavlov proposed that conditioning involved a connection between brain centers for conditioned and unconditioned stimuli. His physiological account of conditioning has been abandoned, but classical conditioning continues to be used to study the neural structures and functions that underlie learning and memory. Forms of classical conditioning that are used for this purpose include, among others, fear conditioning, eyeblink conditioning, and the foot contraction conditioning of Hermissenda crassicornis, a sea-slug. Both fear and eyeblink conditioning involve a neutral stimulus, frequently a tone, becoming paired with an unconditioned stimulus. In the case of eyeblink conditioning, the US is an air-puff, while in fear conditioning the US is threatening or aversive such as a foot shock.

"Available data demonstrate that discrete regions of the cerebellum and associated brainstem areas contain neurons that alter their activity during conditioning – these regions are critical for the acquisition and performance of this simple learning task. It appears that other regions of the brain, including the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex, contribute to the conditioning process, especially when the demands of the task get more complex."

Fear and eyeblink conditioning involve generally non overlapping neural circuitry, but share molecular mechanisms. Fear conditioning occurs in the basolateral amygdala, which receives glutaminergic input directly from thalamic afferents, as well as indirectly from prefrontal projections. The direct projections are sufficient for delay conditioning, but in the case of trace conditioning, where the CS needs to be internally represented despite a lack of external stimulus, indirect pathways are necessary. The anterior cingulate is one candidate for intermediate trace conditioning, but the hippocampus may also play a major role. Presynaptic activation of protein kinase A and postsynaptic activation of NMDA receptors and its signal transduction pathway are necessary for conditioning related plasticity. CREB is also necessary for conditioning related plasticity, and it may induce downstream synthesis of proteins necessary for this to occur. As NMDA receptors are only activated after an increase in presynaptic calcium(thereby releasing the Mg2+ block), they are a potential coincidence detector that could mediate spike timing dependent plasticity. STDP constrains LTP to situations where the CS predicts the US, and LTD to the reverse.

Behavioral therapies

Some therapies associated with classical conditioning are aversion therapy, systematic desensitization and flooding. Aversion therapy is a type of behavior therapy designed to make patients cease an undesirable habit by associating the habit with a strong unpleasant unconditioned stimulus. For example, a medication might be used to associate the taste of alcohol with stomach upset. Systematic desensitization is a treatment for phobias in which the patient is trained to relax while being exposed to progressively more anxiety-provoking stimuli (e.g. angry words). This is an example of counterconditioning, intended to associate the feared stimuli with a response (relaxation) that is incompatible with anxiety Flooding is a form of desensitization that attempts to eliminate phobias and anxieties by repeated exposure to highly distressing stimuli until the lack of reinforcement of the anxiety response causes its extinction. "Flooding" usually involves actual exposure to the stimuli, whereas the term "implosion" refers to imagined exposure, but the two terms are sometimes used synonymously.

Conditioning therapies usually take less time than humanistic therapies.

Conditioned drug response

A stimulus that is present when a drug is administered or consumed may eventually evoke a conditioned physiological response that mimics the effect of the drug. This is sometimes the case with caffeine; habitual coffee drinkers may find that the smell of coffee gives them a feeling of alertness. In other cases, the conditioned response is a compensatory reaction that tends to offset the effects of the drug. For example, if a drug causes the body to become less sensitive to pain, the compensatory conditioned reaction may be one that makes the user more sensitive to pain. This compensatory reaction may contribute to drug tolerance. If so, a drug user may increase the amount of drug consumed in order to feel its effects, and end up taking very large amounts of the drug. In this case a dangerous overdose reaction may occur if the CS happens to be absent, so that the conditioned compensatory effect fails to occur. For example, if the drug has always been administered in the same room, the stimuli provided by that room may produce a conditioned compensatory effect; then an overdose reaction may happen if the drug is administered in a different location where the conditioned stimuli are absent.

Conditioned hunger

Signals that consistently precede food intake can become conditioned stimuli for a set of bodily responses that prepares the body for food and digestion. These reflexive responses include the secretion of digestive juices into the stomach and the secretion of certain hormones into the blood stream, and they induce a state of hunger. An example of conditioned hunger is the "appetizer effect." Any signal that consistently precedes a meal, such as a clock indicating that it is time for dinner, can cause people to feel hungrier than before the signal. The lateral hypothalamus (LH) is involved in the initiation of eating. The nigrostriatal pathway, which includes the substantia nigra, the lateral hypothalamus, and the basal ganglia have been shown to be involved in hunger motivation.

Conditioned emotional response

The influence of classical conditioning can be seen in emotional responses such as phobia, disgust, nausea, anger, and sexual arousal. A familiar example is conditioned nausea, in which the CS is the sight or smell of a particular food that in the past has resulted in an unconditioned stomach upset. Similarly, when the CS is the sight of a dog and the US is the pain of being bitten, the result may be a conditioned fear of dogs. An example of conditioned emotional response is conditioned suppression.

As an adaptive mechanism, emotional conditioning helps shield an individual from harm or prepare it for important biological events such as sexual activity. Thus, a stimulus that has occurred before sexual interaction comes to cause sexual arousal, which prepares the individual for sexual contact. For example, sexual arousal has been conditioned in human subjects by pairing a stimulus like a picture of a jar of pennies with views of an erotic film clip. Similar experiments involving blue gourami fish and domesticated quail have shown that such conditioning can increase the number of offspring. These results suggest that conditioning techniques might help to increase fertility rates in infertile individuals and endangered species.

Pavlovian-instrumental transfer

Pavlovian-instrumental transfer is a phenomenon that occurs when a conditioned stimulus (CS, also known as a "cue") that has been associated with rewarding or aversive stimuli via classical conditioning alters motivational salience and operant behavior. In a typical experiment, a rat is presented with sound-food pairings (classical conditioning). Separately, the rat learns to press a lever to get food (operant conditioning). Test sessions now show that the rat presses the lever faster in the presence of the sound than in silence, although the sound has never been associated with lever pressing.

Pavlovian-instrumental transfer is suggested to play a role in the differential outcomes effect, a procedure which enhances operant discrimination by pairing stimuli with specific outcomes.