Behaviorism is a systematic approach to understanding the behavior of humans and animals. It assumes that behavior is either a reflex evoked by the pairing of certain antecedent stimuli in the environment, or a consequence of that individual's history, including especially reinforcement and punishment contingencies, together with the individual's current motivational state and controlling stimuli. Although behaviorists generally accept the important role of heredity in determining behavior, they focus primarily on environmental events.

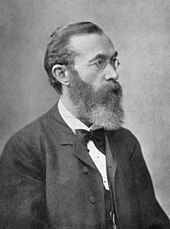

Behaviorism emerged in the early 1900s as a reaction to depth psychology and other traditional forms of psychology, which often had difficulty making predictions that could be tested experimentally, but derived from earlier research in the late nineteenth century, such as when Edward Thorndike pioneered the law of effect, a procedure that involved the use of consequences to strengthen or weaken behavior.

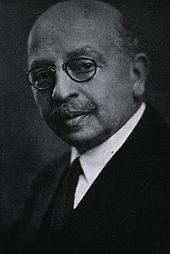

With a 1924 publication, John B. Watson devised methodological behaviorism, which rejected introspective methods and sought to understand behavior by only measuring observable behaviors and events. It was not until the 1930s that B. F. Skinner suggested that covert behavior—including cognition and emotions—is subject to the same controlling variables as observable behavior, which became the basis for his philosophy called radical behaviorism. While Watson and Ivan Pavlov investigated how (conditioned) neutral stimuli elicit reflexes in respondent conditioning, Skinner assessed the reinforcement histories of the discriminative (antecedent) stimuli that emits behavior; the technique became known as operant conditioning.

The application of radical behaviorism—known as applied behavior analysis—is used in a variety of contexts, including, for example, applied animal behavior and organizational behavior management to treatment of mental disorders, such as autism and substance abuse. In addition, while behaviorism and cognitive schools of psychological thought do not agree theoretically, they have complemented each other in the cognitive-behavior therapies, which have demonstrated utility in treating certain pathologies, including simple phobias, PTSD, and mood disorders.

Branches Of Behaviorisms

The titles given to the various branches of behaviorism include:

- Behavioral genetics: Proposed in 1869 by Francis Galton, a relative of Charles Darwin.

- Interbehaviorism: Proposed by Jacob Robert Kantor before B. F. Skinner's writings.

- Methodological behaviorism: John B. Watson's behaviorism states that only public events (motor behaviors of an individual) can be objectively observed. Although it was still acknowledged that thoughts and feelings exist, they were not considered part of the science of behavior. It also laid the theoretical foundation for the early approach behavior modification in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Psychological behaviorism: As proposed by Arthur W. Staats, unlike the previous behaviorisms of Skinner, Hull, and Tolman, was based upon a program of human research involving various types of human behavior. Psychological behaviorism introduces new principles of human learning. Humans learn not only by animal learning principles but also by special human learning principles. Those principles involve humans' uniquely huge learning ability. Humans learn repertoires that enable them to learn other things. Human learning is thus cumulative. No other animal demonstrates that ability, making the human species unique.

- Radical behaviorism: Skinner's philosophy is an extension of Watson's form of behaviorism by theorizing that processes within the organism—particularly, private events, such as thoughts and feelings—are also part of the science of behavior, and suggests that environmental variables control these internal events just as they control observable behaviors. Although private events cannot be directly seen by others, they are later determined through the species' overt behavior. Radical behaviorism forms the core philosophy behind behavior analysis. Willard Van Orman Quine used many of radical behaviorism's ideas in his study of knowledge and language.

- Teleological behaviorism: Proposed by Howard Rachlin, post-Skinnerian, purposive, close to microeconomics. Focuses on objective observation as opposed to cognitive processes.

- Theoretical behaviorism: Proposed by J. E. R. Staddon, adds a concept of internal state to allow for the effects of context. According to theoretical behaviorism, a state is a set of equivalent histories, i.e., past histories in which members of the same stimulus class produce members of the same response class (i.e., B. F. Skinner's concept of the operant). Conditioned stimuli are thus seen to control neither stimulus nor response but state. Theoretical behaviorism is a logical extension of Skinner's class-based (generic) definition of the operant.

Two subtypes of theoretical behaviorism are:

- Hullian and post-Hullian: theoretical, group data, not dynamic, physiological

- Purposive: Tolman's behavioristic anticipation of cognitive psychology

Modern-day theory: radical behaviorism

B. F. Skinner proposed radical behaviorism as the conceptual underpinning of the experimental analysis of behavior. This viewpoint differs from other approaches to behavioral research in various ways, but, most notably here, it contrasts with methodological behaviorism in accepting feelings, states of mind and introspection as behaviors also subject to scientific investigation. Like methodological behaviorism, it rejects the reflex as a model of all behavior, and it defends the science of behavior as complementary to but independent of physiology. Radical behaviorism overlaps considerably with other western philosophical positions, such as American pragmatism.

Although John B. Watson mainly emphasized his position of methodological behaviorism throughout his career, Watson and Rosalie Rayner conducted the renowned Little Albert experiment (1920), a study in which Ivan Pavlov's theory to respondent conditioning was first applied to eliciting a fearful reflex of crying in a human infant, and this became the launching point for understanding covert behavior (or private events) in radical behaviorism. However, Skinner felt that aversive stimuli should only be experimented on with animals and spoke out against Watson for testing something so controversial on a human.

In 1959, Skinner observed the emotions of two pigeons by noting that they appeared angry because their feathers ruffled. The pigeons were placed together in an operant chamber, where they were aggressive as a consequence of previous reinforcement in the environment. Through stimulus control and subsequent discrimination training, whenever Skinner turned off the green light, the pigeons came to notice that the food reinforcer is discontinued following each peck and responded without aggression. Skinner concluded that humans also learn aggression and possess such emotions (as well as other private events) no differently than do nonhuman animals.

Experimental and conceptual innovations

As experimental behavioural psychology is related to behavioral neuroscience, we can date the first researches in the area were done in the beginning of 19th century.

Later, this essentially philosophical position gained strength from the success of Skinner's early experimental work with rats and pigeons, summarized in his books The Behavior of Organisms and Schedules of Reinforcement. Of particular importance was his concept of the operant response, of which the canonical example was the rat's lever-press. In contrast with the idea of a physiological or reflex response, an operant is a class of structurally distinct but functionally equivalent responses. For example, while a rat might press a lever with its left paw or its right paw or its tail, all of these responses operate on the world in the same way and have a common consequence. Operants are often thought of as species of responses, where the individuals differ but the class coheres in its function-shared consequences with operants and reproductive success with species. This is a clear distinction between Skinner's theory and S–R theory.

Skinner's empirical work expanded on earlier research on trial-and-error learning by researchers such as Thorndike and Guthrie with both conceptual reformulations—Thorndike's notion of a stimulus-response "association" or "connection" was abandoned; and methodological ones—the use of the "free operant", so-called because the animal was now permitted to respond at its own rate rather than in a series of trials determined by the experimenter procedures. With this method, Skinner carried out substantial experimental work on the effects of different schedules and rates of reinforcement on the rates of operant responses made by rats and pigeons. He achieved remarkable success in training animals to perform unexpected responses, to emit large numbers of responses, and to demonstrate many empirical regularities at the purely behavioral level. This lent some credibility to his conceptual analysis. It is largely his conceptual analysis that made his work much more rigorous than his peers, a point which can be seen clearly in his seminal work Are Theories of Learning Necessary? in which he criticizes what he viewed to be theoretical weaknesses then common in the study of psychology. An important descendant of the experimental analysis of behavior is the Society for Quantitative Analysis of Behavior.

Relation to language

As Skinner turned from experimental work to concentrate on the philosophical underpinnings of a science of behavior, his attention turned to human language with his 1957 book Verbal Behavior and other language-related publications; Verbal Behavior laid out a vocabulary and theory for functional analysis of verbal behavior, and was strongly criticized in a review by Noam Chomsky.

Skinner did not respond in detail but claimed that Chomsky failed to understand his ideas, and the disagreements between the two and the theories involved have been further discussed. Innateness theory, which has been heavily critiqued, is opposed to behaviorist theory which claims that language is a set of habits that can be acquired by means of conditioning. According to some, the behaviorist account is a process which would be too slow to explain a phenomenon as complicated as language learning. What was important for a behaviorist's analysis of human behavior was not language acquisition so much as the interaction between language and overt behavior. In an essay republished in his 1969 book Contingencies of Reinforcement, Skinner took the view that humans could construct linguistic stimuli that would then acquire control over their behavior in the same way that external stimuli could. The possibility of such "instructional control" over behavior meant that contingencies of reinforcement would not always produce the same effects on human behavior as they reliably do in other animals. The focus of a radical behaviorist analysis of human behavior therefore shifted to an attempt to understand the interaction between instructional control and contingency control, and also to understand the behavioral processes that determine what instructions are constructed and what control they acquire over behavior. Recently, a new line of behavioral research on language was started under the name of relational frame theory.

Education

Behaviourism focuses on one particular view of learning: a change in external behaviour achieved through using reinforcement and repetition (Rote learning) to shape behavior of learners. Skinner found that behaviors could be shaped when the use of reinforcement was implemented. Desired behavior is rewarded, while the undesired behavior is not rewarded. Incorporating behaviorism into the classroom allowed educators to assist their students in excelling both academically and personally. In the field of language learning, this type of teaching was called the audio-lingual method, characterised by the whole class using choral chanting of key phrases, dialogues and immediate correction.

Within the behaviourist view of learning, the "teacher" is the dominant person in the classroom and takes complete control, evaluation of learning comes from the teacher who decides what is right or wrong. The learner does not have any opportunity for evaluation or reflection within the learning process, they are simply told what is right or wrong. The conceptualization of learning using this approach could be considered "superficial," as the focus is on external changes in behaviour, i.e., not interested in the internal processes of learning leading to behaviour change and has no place for the emotions involved in the process.

Operant conditioning

Operant conditioning was developed by B.F. Skinner in 1937 and deals with the management of environmental contingencies to change behavior. In other words, behavior is controlled by historical consequential contingencies, particularly reinforcement—a stimulus that increases the probability of performing behaviors, and punishment—a stimulus that decreases such probability. The core tools of consequences are either positive (presenting stimuli following a response), or negative (withdrawn stimuli following a response).

The following descriptions explains the concepts of four common types of consequences in operant conditioning:

- Positive reinforcement: Providing a stimulus that an individual enjoys, seeks, or craves, in order to reinforce desired behaviors. For example, when a person is teaching a dog to sit, they pair the command "sit" with a treat. The treat is the positive reinforcement to the behavior of sitting. The key to making positive reinforcement effect is to reward the behavior immediately.

- Negative reinforcement: Removing a stimulus that an individual does not desire to reinforce desired behaviors. For example, a child hates being nagged to clean his room. His mother reinforces his room cleaning by removing the undesired stimulus of nagging after he has cleaned. Another example would be putting on sunscreen before going outside. The negative effect is getting a sunburn, so by putting on sunscreen, the behavior in this case, you avoid the stimulus of getting a sunburn.

- Positive punishment: Providing a stimulus that an individual does not desire to decrease undesired behaviors. An example of this would be spanking. If a child is doing something they have been warned not to do, the parent might spank them. The undesired stimulus would be the spanking, and by adding this stimulus, the goal is to have that behavior avoided. The key to this technique is that even though the title says positive, the meaning of positive here is "to add to." So, in order to stop the behavior, the parent adds the adverse stimulus (spanking). The biggest problem with this type of training though is that the trainee doesn't usually learn the desired behavior, rather it teaches the trainee to avoid the punisher.

- Negative punishment: Removing a stimulus that an individual desires in order to decrease undesired behaviors. An example of this would be grounding a child for failing a test. Grounding in this example is taking away the child's ability to play video games. As long as it is clear that the ability to play video games was taken away because they failed a test, this is negative punishment. The key here is the connection to the behavior and the result of the behavior.

Classical experiment in operant conditioning, for example, the Skinner Box, "puzzle box" or operant conditioning chamber to test the effects of operant conditioning principles on rats, cats and other species. From the study of Skinner box, he discovered that the rats learned very effectively if they were rewarded frequently with food. Skinner also found that he could shape the rats' behavior through the use of rewards, which could, in turn, be applied to human learning as well.

Skinner's model was based on the premise that reinforcement is used for the desired actions or responses while punishment was used to stop the responses of the undesired actions that are not. This theory proved that humans or animals will repeat any action that leads to a positive outcome, and avoiding any action that leads to a negative outcome. The experiment with the pigeons showed that a positive outcome leads to learned behavior since the pigeon learned to peck the disc in return for the reward of food.

These historical consequential contingencies subsequently lead to (antecedent) stimulus control, but in contrast to respondent conditioning where antecedent stimuli elicit reflexive behavior, operant behavior is only emitted and therefore does not force its occurrence. It includes the following controlling stimuli:

- Discriminative stimulus (Sd): An antecedent stimulus that increases the chance of the organism engaging in a behavior. One example of this occurred in Skinner's laboratory. Whenever the green light (Sd) appeared, it signaled the pigeon to perform the behavior of pecking because it learned in the past that each time it pecked, food was presented (the positive reinforcing stimulus).

- Stimulus delta (S-delta): An antecedent stimulus that signals the organism not to perform a behavior since it was extinguished or punished in the past. One notable instance of this occurs when a person stops their car immediately after the traffic light turns red (S-delta). However, the person could decide to drive through the red light, but subsequently receive a speeding ticket (the positive punishing stimulus), so this behavior will potentially not reoccur following the presence of the S-delta.

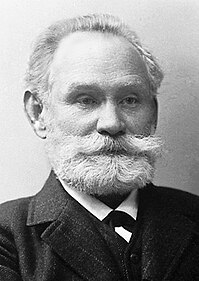

Respondent conditioning

Although operant conditioning plays the largest role in discussions of behavioral mechanisms, respondent conditioning (also called Pavlovian or classical conditioning) is also an important behavior-analytic process that needs not refer to mental or other internal processes. Pavlov's experiments with dogs provide the most familiar example of the classical conditioning procedure. In the beginning, the dog was provided meat (unconditioned stimulus, UCS, naturally elicit a response that is not controlled) to eat, resulting in increased salivation (unconditioned response, UCR, which means that a response is naturally caused by UCS). Afterward, a bell ring was presented together with food to the dog. Although bell ring was a neutral stimulus (NS, meaning that the stimulus did not have any effect), dog would start to salivate when only hearing a bell ring after a number of pairings. Eventually, the neutral stimulus (bell ring) became conditioned. Therefore, salivation was elicited as a conditioned response (the response same as the unconditioned response), pairing up with meat—the conditioned stimulus) Although Pavlov proposed some tentative physiological processes that might be involved in classical conditioning, these have not been confirmed. The idea of classical conditioning helped behaviorist John Watson discover the key mechanism behind how humans acquire the behaviors that they do, which was to find a natural reflex that produces the response being considered.

Watson's "Behaviourist Manifesto" has three aspects that deserve special recognition: one is that psychology should be purely objective, with any interpretation of conscious experience being removed, thus leading to psychology as the "science of behaviour"; the second one is that the goals of psychology should be to predict and control behaviour (as opposed to describe and explain conscious mental states); the third one is that there is no notable distinction between human and non-human behaviour. Following Darwin's theory of evolution, this would simply mean that human behaviour is just a more complex version in respect to behaviour displayed by other species.

In philosophy

Behaviorism is a psychological movement that can be contrasted with philosophy of mind. The basic premise of behaviorism is that the study of behavior should be a natural science, such as chemistry or physics. Initially behaviorism rejected any reference to hypothetical inner states of organisms as causes for their behavior, but B.F. Skinner's radical behaviorism reintroduced reference to inner states and also advocated for the study of thoughts and feelings as behaviors subject to the same mechanisms as external behavior. Behaviorism takes a functional view of behavior. According to Edmund Fantino and colleagues: "Behavior analysis has much to offer the study of phenomena normally dominated by cognitive and social psychologists. We hope that successful application of behavioral theory and methodology will not only shed light on central problems in judgment and choice but will also generate greater appreciation of the behavioral approach."

Behaviorist sentiments are not uncommon within philosophy of language and analytic philosophy. It is sometimes argued that Ludwig Wittgenstein defended a logical behaviorist position (e.g., the beetle in a box argument). In logical positivism (as held, e.g., by Rudolf Carnap and Carl Hempel), the meaning of psychological statements are their verification conditions, which consist of performed overt behavior. W. V. O. Quine made use of a type of behaviorism, influenced by some of Skinner's ideas, in his own work on language. Quine's work in semantics differed substantially from the empiricist semantics of Carnap which he attempted to create an alternative to, couching his semantic theory in references to physical objects rather than sensations. Gilbert Ryle defended a distinct strain of philosophical behaviorism, sketched in his book The Concept of Mind. Ryle's central claim was that instances of dualism frequently represented "category mistakes", and hence that they were really misunderstandings of the use of ordinary language. Daniel Dennett likewise acknowledges himself to be a type of behaviorist, though he offers extensive criticism of radical behaviorism and refutes Skinner's rejection of the value of intentional idioms and the possibility of free will.

This is Dennett's main point in "Skinner Skinned." Dennett argues that there is a crucial difference between explaining and explaining away… If our explanation of apparently rational behavior turns out to be extremely simple, we may want to say that the behavior was not really rational after all. But if the explanation is very complex and intricate, we may want to say not that the behavior is not rational, but that we now have a better understanding of what rationality consists in. (Compare: if we find out how a computer program solves problems in linear algebra, we don't say it's not really solving them, we just say we know how it does it. On the other hand, in cases like Weizenbaum's ELIZA program, the explanation of how the computer carries on a conversation is so simple that the right thing to say seems to be that the machine isn't really carrying on a conversation, it's just a trick.)

— Curtis Brown, "Behaviorism: Skinner and Dennett", Philosophy of Mind

Law of effect and trace conditioning

- Law of effect: Although Edward Thorndike's methodology mainly dealt with reinforcing observable behavior, it viewed cognitive antecedents as the causes of behavior, and was theoretically much more similar to the cognitive-behavior therapies than classical (methodological) or modern-day (radical) behaviorism. Nevertheless, Skinner's operant conditioning was heavily influenced by the Law of Effect's principle of reinforcement.

- Trace conditioning: Akin to B.F. Skinner's radical behaviorism, it is a respondent conditioning technique based on Ivan Pavlov's concept of a "memory trace" in which the observer recalls the conditioned stimulus (CS), with the memory or recall being the unconditioned response (UR). There is also a time delay between the CS and unconditioned stimulus (US), causing the conditioned response (CR)—particularly the reflex—to be faded over time.

Molecular versus molar behaviorism

Skinner's view of behavior is most often characterized as a "molecular" view of behavior; that is, behavior can be decomposed into atomistic parts or molecules. This view is inconsistent with Skinner's complete description of behavior as delineated in other works, including his 1981 article "Selection by Consequences". Skinner proposed that a complete account of behavior requires understanding of selection history at three levels: biology (the natural selection or phylogeny of the animal); behavior (the reinforcement history or ontogeny of the behavioral repertoire of the animal); and for some species, culture (the cultural practices of the social group to which the animal belongs). This whole organism then interacts with its environment. Molecular behaviorists use notions from melioration theory, negative power function discounting or additive versions of negative power function discounting.

Molar behaviorists, such as Howard Rachlin, Richard Herrnstein, and William Baum, argue that behavior cannot be understood by focusing on events in the moment. That is, they argue that behavior is best understood as the ultimate product of an organism's history and that molecular behaviorists are committing a fallacy by inventing fictitious proximal causes for behavior. Molar behaviorists argue that standard molecular constructs, such as "associative strength", are better replaced by molar variables such as rate of reinforcement. Thus, a molar behaviorist would describe "loving someone" as a pattern of loving behavior over time; there is no isolated, proximal cause of loving behavior, only a history of behaviors (of which the current behavior might be an example) that can be summarized as "love".

Theoretical behaviorism

Skinner's radical behaviorism has been highly successful experimentally, revealing new phenomena with new methods, but Skinner's dismissal of theory limited its development. Theoretical behaviorism recognized that a historical system, an organism, has a state as well as sensitivity to stimuli and the ability to emit responses. Indeed, Skinner himself acknowledged the possibility of what he called "latent" responses in humans, even though he neglected to extend this idea to rats and pigeons. Latent responses constitute a repertoire, from which operant reinforcement can select. Theoretical behaviorism links between the brain and the behavior that provides a real understanding of the behavior. Rather than a mental presumption of how brain-behavior relates.

Behavior analysis and culture

Cultural analysis has always been at the philosophical core of radical behaviorism from the early days (as seen in Skinner's Walden Two, Science & Human Behavior, Beyond Freedom & Dignity, and About Behaviorism).

During the 1980s, behavior analysts, most notably Sigrid Glenn, had a productive interchange with cultural anthropologist Marvin Harris (the most notable proponent of "cultural materialism") regarding interdisciplinary work. Very recently, behavior analysts have produced a set of basic exploratory experiments in an effort toward this end. Behaviorism is also frequently used in game development, although this application is controversial.

Behavior informatics and behavior computing

With the fast growth of big behavioral data and applications, behavior analysis is ubiquitous. Understanding behavior from the informatics and computing perspective becomes increasingly critical for in-depth understanding of what, why and how behaviors are formed, interact, evolve, change and affect business and decision. Behavior informatics and behavior computing deeply explore behavior intelligence and behavior insights from the informatics and computing perspectives.

Criticisms and limitations

In the second half of the 20th century, behaviorism was largely eclipsed as a result of the cognitive revolution. This shift was due to radical behaviorism being highly criticized for not examining mental processes, and this led to the development of the cognitive therapy movement. In the mid-20th century, three main influences arose that would inspire and shape cognitive psychology as a formal school of thought:

- Noam Chomsky's 1959 critique of behaviorism, and empiricism more generally, initiated what would come to be known as the "cognitive revolution".

- Developments in computer science would lead to parallels being drawn between human thought and the computational functionality of computers, opening entirely new areas of psychological thought. Allen Newell and Herbert Simon spent years developing the concept of artificial intelligence (AI) and later worked with cognitive psychologists regarding the implications of AI. The effective result was more of a framework conceptualization of mental functions with their counterparts in computers (memory, storage, retrieval, etc.)

- Formal recognition of the field involved the establishment of research institutions such as George Mandler's Center for Human Information Processing in 1964. Mandler described the origins of cognitive psychology in a 2002 article in the Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences

In the early years of cognitive psychology, behaviorist critics held that the empiricism it pursued was incompatible with the concept of internal mental states. Cognitive neuroscience, however, continues to gather evidence of direct correlations between physiological brain activity and putative mental states, endorsing the basis for cognitive psychology.

Behavior therapy

Behavior therapy is a term referring to different types of therapies that treat mental health disorders. It identifies and helps change people's unhealthy behaviors or destructive behaviors through learning theory and conditioning. Ivan Pavlov's classical conditioning, as well as counterconditioning are the basis for much of clinical behavior therapy, but also includes other techniques, including operant conditioning—or contingency management, and modeling (sometimes called observational learning). A frequently noted behavior therapy is systematic desensitization (graduated exposure therapy), which was first demonstrated by Joseph Wolpe and Arnold Lazarus.

21st-century behaviorism (behavior analysis)

Applied behavior analysis (ABA)—also called behavioral engineering—is a scientific discipline that applies the principles of behavior analysis to change behavior. ABA derived from much earlier research in the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, which was founded by B.F. Skinner and his colleagues at Harvard University. Nearly a decade after the study "The psychiatric nurse as a behavioral engineer" (1959) was published in that journal, which demonstrated how effective the token economy was in reinforcing more adaptive behavior for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and intellectual disability, it led to researchers at the University of Kansas to start the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis in 1968.

Although ABA and behavior modification are similar behavior-change technologies in that the learning environment is modified through respondent and operant conditioning, behavior modification did not initially address the causes of the behavior (particularly, the environmental stimuli that occurred in the past), or investigate solutions that would otherwise prevent the behavior from reoccurring. As the evolution of ABA began to unfold in the mid-1980s, functional behavior assessments (FBAs) were developed to clarify the function of that behavior, so that it is accurately determined which differential reinforcement contingencies will be most effective and less likely for aversive consequences to be administered. In addition, methodological behaviorism was the theory underpinning behavior modification since private events were not conceptualized during the 1970s and early 1980s, which contrasted from the radical behaviorism of behavior analysis. ABA—the term that replaced behavior modification—has emerged into a thriving field.

The independent development of behaviour analysis outside the United States also continues to develop. In the US, the American Psychological Association (APA) features a subdivision for Behavior Analysis, titled APA Division 25: Behavior Analysis, which has been in existence since 1964, and the interests among behavior analysts today are wide-ranging, as indicated in a review of the 30 Special Interest Groups (SIGs) within the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI). Such interests include everything from animal behavior and environmental conservation, to classroom instruction (such as direct instruction and precision teaching), verbal behavior, developmental disabilities and autism, clinical psychology (i.e., forensic behavior analysis), behavioral medicine (i.e., behavioral gerontology, AIDS prevention, and fitness training), and consumer behavior analysis.

The field of applied animal behavior—a sub-discipline of ABA that involves training animals—is regulated by the Animal Behavior Society, and those who practice this technique are called applied animal behaviorists. Research on applied animal behavior has been frequently conducted in the Applied Animal Behaviour Science journal since its founding in 1974.

ABA has also been particularly well-established in the area of developmental disabilities since the 1960s, but it was not until the late 1980s that individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders were beginning to grow so rapidly and groundbreaking research was being published that parent advocacy groups started demanding for services throughout the 1990s, which encouraged the formation of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board, a credentialing program that certifies professionally trained behavior analysts on the national level to deliver such services. Nevertheless, the certification is applicable to all human services related to the rather broad field of behavior analysis (other than the treatment for autism), and the ABAI currently has 14 accredited MA and Ph.D. programs for comprehensive study in that field.

Early behavioral interventions (EBIs) based on ABA are empirically validated for teaching children with autism and has been proven as such for over the past five decades. Since the late 1990s and throughout the twenty-first century, early ABA interventions have also been identified as the treatment of choice by the US Surgeon General, American Academy of Pediatrics, and US National Research Council.

Discrete trial training—also called early intensive behavioral intervention—is the traditional EBI technique implemented for thirty to forty hours per week that instructs a child to sit in a chair, imitate fine and gross motor behaviors, as well as learn eye contact and speech, which are taught through shaping, modeling, and prompting, with such prompting being phased out as the child begins mastering each skill. When the child becomes more verbal from discrete trials, the table-based instructions are later discontinued, and another EBI procedure known as incidental teaching is introduced in the natural environment by having the child ask for desired items kept out of their direct access, as well as allowing the child to choose the play activities that will motivate them to engage with their facilitators before teaching the child how to interact with other children their own age.

A related term for incidental teaching, called pivotal response treatment (PRT), refers to EBI procedures that exclusively entail twenty-five hours per week of naturalistic teaching (without initially using discrete trials). Current research is showing that there is a wide array of learning styles and that is the children with receptive language delays who initially require discrete trials to acquire speech.

Organizational behavior management, which applies contingency management procedures to model and reinforce appropriate work behavior for employees in organizations, has developed a particularly strong following within ABA, as evidenced by the formation of the OBM Network and Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, which was rated the third-highest impact journal in applied psychology by ISI JOBM rating.

Modern-day clinical behavior analysis has also witnessed a massive resurgence in research, with the development of relational frame theory (RFT), which is described as an extension of verbal behavior and a "post-Skinnerian account of language and cognition." RFT also forms the empirical basis for acceptance and commitment therapy, a therapeutic approach to counseling often used to manage such conditions as anxiety and obesity that consists of acceptance and commitment, value-based living, cognitive defusion, counterconditioning (mindfulness), and contingency management (positive reinforcement). Another evidence-based counseling technique derived from RFT is the functional analytic psychotherapy known as behavioral activation that relies on the ACL model—awareness, courage, and love—to reinforce more positive moods for those struggling with depression.

Incentive-based contingency management (CM) is the standard of care for adults with substance-use disorders; it has also been shown to be highly effective for other addictions (i.e., obesity and gambling). Although it does not directly address the underlying causes of behavior, incentive-based CM is highly behavior analytic as it targets the function of the client's motivational behavior by relying on a preference assessment, which is an assessment procedure that allows the individual to select the preferred reinforcer (in this case, the monetary value of the voucher, or the use of other incentives, such as prizes). Another evidence-based CM intervention for substance abuse is community reinforcement approach and family training that uses FBAs and counterconditioning techniques—such as behavioral skills training and relapse prevention—to model and reinforce healthier lifestyle choices which promote self-management of abstinence from drugs, alcohol, or cigarette smoking during high-risk exposure when engaging with family members, friends, and co-workers.

While schoolwide positive behavior support consists of conducting assessments and a task analysis plan to differentially reinforce curricular supports that replace students' disruptive behavior in the classroom, pediatric feeding therapy incorporates a liquid chaser and chin feeder to shape proper eating behavior for children with feeding disorders. Habit reversal training, an approach firmly grounded in counterconditioning which uses contingency management procedures to reinforce alternative behavior, is currently the only empirically validated approach for managing tic disorders.

Some studies on exposure (desensitization) therapies—which refer to an array of interventions based on the respondent conditioning procedure known as habituation and typically infuses counterconditioning procedures, such as meditation and breathing exercises—have recently been published in behavior analytic journals since the 1990s, as most other research are conducted from a cognitive-behavior therapy framework. When based on a behavior analytic research standpoint, FBAs are implemented to precisely outline how to employ the flooding form of desensitization (also called direct exposure therapy) for those who are unsuccessful in overcoming their specific phobia through systematic desensitization (also known as graduated exposure therapy). These studies also reveal that systematic desensitization is more effective for children if used in conjunction with shaping, which is further termed contact desensitization, but this comparison has yet to be substantiated with adults.

Other widely published behavior analytic journals include Behavior Modification, The Behavior Analyst, Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, Behavior and Philosophy, Behavior and Social Issues, and The Psychological Record.

Cognitive-behavior therapy

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) is a behavior therapy discipline that often overlaps considerably with the clinical behavior analysis subfield of ABA, but differs in that it initially incorporates cognitive restructuring and emotional regulation to alter a person's cognition and emotions.

A popularly noted counseling intervention known as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) includes the use of a chain analysis, as well as cognitive restructuring, emotional regulation, distress tolerance, counterconditioning (mindfulness), and contingency management (positive reinforcement). DBT is quite similar to acceptance and commitment therapy, but contrasts in that it derives from a CBT framework. Although DBT is most widely researched for and empirically validated to reduce the risk of suicide in psychiatric patients with borderline personality disorder, it can often be applied effectively to other mental health conditions, such as substance abuse, as well as mood and eating disorders.

Most research on exposure therapies (also called desensitization)—ranging from eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy to exposure and response prevention—are conducted through a CBT framework in non-behavior analytic journals, and these enhanced exposure therapies are well-established in the research literature for treating phobic, post-traumatic stress, and other anxiety disorders (such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD).

Cognitive-based behavioral activation (BA)—the psychotherapeutic approach used for depression—is shown to be highly effective and is widely used in clinical practice. Some large randomized control trials have indicated that cognitive-based BA is as beneficial as antidepressant medications but more efficacious than traditional cognitive therapy. Other commonly used clinical treatments derived from behavioral learning principles that are often implemented through a CBT model include community reinforcement approach and family training, and habit reversal training for substance abuse and tics, respectively.