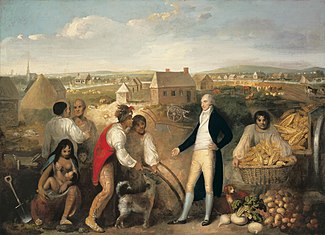

The cultural assimilation of Native Americans refers to a series of efforts by the United States to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream European–American culture between the years of 1790 and 1920. George Washington and Henry Knox were first to propose, in the American context, the cultural assimilation of Native Americans. They formulated a policy to encourage the so-called "civilizing process". With increased waves of immigration from Europe, there was growing public support for education to encourage a standard set of cultural values and practices to be held in common by the majority of citizens. Education was viewed as the primary method in the acculturation process for minorities.

Americanization policies were based on the idea that when indigenous people learned customs and values of the United States, they would be able to merge tribal traditions with American culture and peacefully join the majority of the society. After the end of the Indian Wars, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the federal government outlawed the practice of traditional religious ceremonies. It established Native American boarding schools which children were required to attend. In these schools they were forced to speak English, study standard subjects, attend church, and leave tribal traditions behind.

The Dawes Act of 1887, which allotted tribal lands in severalty to individuals, was seen as a way to create individual homesteads for Native Americans. Land allotments were made in exchange for Native Americans becoming US citizens and giving up some forms of tribal self-government and institutions. It resulted in the transfer of an estimated total of 93 million acres (380,000 km2) from Native American control. Most was sold to individuals or given out free through the Homestead law, or given directly to Indians as individuals. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 was also part of Americanization policy; it gave full citizenship to all Indians living on reservations. The leading opponent of forced assimilation was John Collier, who directed the federal Office of Indian Affairs from 1933 to 1945, and tried to reverse many of the established policies.

Europeans and Native Americans in North America, 1601–1776

Epidemiological and archeological work has established the effects of increased immigration of children accompanying families from Central Africa to North America between 1634 and 1640. They came from areas where smallpox was endemic in Europea, and passed on the disease to indigenous people. Tribes such as the Huron-Wendat and others in the Northeast particularly suffered devastating epidemics after 1634.

During this period European powers fought to acquire cultural and economic control of North America, just as they were doing in Europe. At the same time, indigenous peoples competed for dominance in the European fur trade and hunting areas. The European colonial powers sought to hire Native American tribes as auxiliary forces in their North American armies, otherwise composed mostly of colonial militia in the early conflicts. In many cases indigenous warriors formed the great majority of fighting forces, which deepened some of their rivalries. To secure the help of the tribes, the Europeans offered goods and signed treaties. The treaties usually promised that the European power would honor the tribe's traditional lands and independence. In addition, the indigenous peoples formed alliances for their own reasons, wanting to keep allies in the fur and gun trades, positioning European allies against their traditional enemies among other tribes, etc. Many Native American tribes took part in King William's War (1689–1697), Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) (War of the Spanish Succession), Dummer's War (c. 1721–1725), and the French and Indian War (1754–1763) (Seven Years' War).

As the dominant power after the Seven Years' War, Great Britain instituted the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to try to protect indigenous peoples' territory from colonial encroachment of peoples from east of the Appalachian Mountains. The document defined a boundary to demacarte Native American territory from that of the European-American settlers. Despite the intentions of the Crown, the proclamation did not effectively prevent colonists from continuing to migrate westward. The British did not have sufficient forces to patrol the border and keep out migrating colonists. From the perspective of the colonists, the proclamation served as one of the Intolerable Acts and one of the 27 colonial grievances that would lead to the American Revolution and eventual independence from Britain.

The United States and Native Americans, 1776–1860

The most important facet of the foreign policy of the newly independent United States was primarily concerned with devising a policy to deal with the various Native American tribes it bordered. To this end, they largely continued the practises that had been adopted since colonial times by settlers and European governments. They realized that good relations with bordering tribes were important for political and trading reasons, but they also reserved the right to abandon these good relations to conquer and absorb the lands of their enemies and allies alike as the American frontier moved west. The United States continued the use of Native Americans as allies, including during the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. As relations with Britain and Spain normalized during the early 19th century, the need for such friendly relations ended. It was no longer necessary to "woo" the tribes to prevent the other powers from allying with them against the United States. Now, instead of a buffer against European powers, the tribes often became viewed as an obstacle in the expansion of the United States.

George Washington formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process. He had a six-point plan for civilization which included:

- impartial justice toward Native Americans

- regulated buying of Native American lands

- promotion of commerce

- promotion of experiments to civilize or improve Native American society

- presidential authority to give presents

- punishing those who violated Native American rights.

Robert Remini, a historian, wrote that "once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans". The United States appointed agents, like Benjamin Hawkins, to live among the Native Americans and to teach them how to live like whites.

How different would be the sensation of a philosophic mind to reflect that instead of exterminating a part of the human race by our modes of population that we had persevered through all difficulties and at last had imparted our Knowledge of cultivating and the arts, to the Aboriginals of the Country by which the source of future life and happiness had been preserved and extended. But it has been conceived to be impracticable to civilize the Indians of North America – This opinion is probably more convenient than just.

— Henry Knox to George Washington, 1790s.

Indian removal

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 characterized the U.S. government policy of Indian removal, which called for the forced relocation of Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river. While it did not authorize the forced removal of the indigenous tribes, it authorized the President to negotiate land exchange treaties with tribes located in lands of the United States. The Intercourse Law of 1834 prohibited United States citizens from entering tribal lands granted by such treaties without permission, though it was often ignored.

On September 27, 1830, the Choctaws signed Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek and the first Native American tribe was to be voluntarily removed. The agreement represented one of the largest transfers of land that was signed between the U.S. Government and Native Americans without being instigated by warfare. By the treaty, the Choctaws signed away their remaining traditional homelands, opening them up for American settlement in Mississippi Territory.

While the Indian Removal Act made the relocation of the tribes voluntary, it was often abused by government officials. The best-known example is the Treaty of New Echota. It was negotiated and signed by a small fraction of Cherokee tribal members, not the tribal leadership, on December 29, 1835. While tribal leaders objected to Washington, DC and the treaty was revised in 1836, the state of Georgia proceeded to act against the Cherokee tribe. The tribe was forced to relocate in 1838. An estimated 4,000 Cherokees died in the march, now known as the Trail of Tears.

In the decades that followed, white settlers encroached even into the western lands set aside for Native Americans. American settlers eventually made homesteads from coast to coast, just as the Native Americans had before them. No tribe was untouched by the influence of white traders, farmers, and soldiers.

Office of Indian Affairs

The Office of Indian Affairs (Bureau of Indian Affairs as of 1947) was established on March 11, 1824, as an office of the United States Department of War, an indication of the state of relations with the Indians. It became responsible for negotiating treaties and enforcing conditions, at least for Native Americans. In 1849 the bureau was transferred to the Department of the Interior as so many of its responsibilities were related to the holding and disposition of large land assets.

In 1854 Commissioner George W. Manypenny called for a new code of regulations. He noted that there was no place in the West where the Indians could be placed with a reasonable hope that they might escape conflict with white settlers. He also called for the Intercourse Law of 1834 to be revised, as its provisions had been aimed at individual intruders on Indian territory rather than at organized expeditions.

In 1858 the succeeding Commissioner, Charles Mix, noted that the repeated removal of tribes had prevented them from acquiring a taste for European way of life. In 1862 Secretary of the Interior Caleb B. Smith questioned the wisdom of treating tribes as quasi-independent nations. Given the difficulties of the government in what it considered good efforts to support separate status for Native Americans, appointees and officials began to consider a policy of Americanization instead.

Americanization and assimilation (1857–1920)

The movement to reform Indian administration and assimilate Indians as citizens originated in the pleas of people who lived in close association with the natives and were shocked by the fraudulent and indifferent management of their affairs. They called themselves "Friends of the Indian" and lobbied officials on their behalf. Gradually the call for change was taken up by Eastern reformers. Typically the reformers were Protestants from well organized denominations who considered assimilation necessary to the Christianizing of the Indians; Catholics were also involved. The 19th century was a time of major efforts in evangelizing missionary expeditions to all non-Christian people. In 1865 the government began to make contracts with various missionary societies to operate Indian schools for teaching citizenship, English, and agricultural and mechanical arts, and decades later was continued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Grant's "Peace Policy"

In his State of the Union Address on December 4, 1871, Ulysses Grant stated that "the policy pursued toward the Indians has resulted favorably ... many tribes of Indians have been induced to settle upon reservations, to cultivate the soil, to perform productive labor of various kinds, and to partially accept civilization. They are being cared for in such a way, it is hoped, as to induce those still pursuing their old habits of life to embrace the only opportunity which is left them to avoid extermination." The emphasis became using civilian workers (not soldiers) to deal with reservation life, especially Protestant and Catholic organizations. The Quakers had promoted the peace policy in the expectation that applying Christian principles to Indian affairs would eliminate corruption and speed assimilation. Most Indians joined churches but there were unexpected problems, such as rivalry between Protestants and Catholics for control of specific reservations in order to maximize the number of souls converted.

The Quakers were motivated by high ideals, played down the role of conversion, and worked well with the Indians. They had been highly organized and motivated by the anti-slavery crusade, and after the Civil War expanded their energies to include both ex-slaves and the western tribes. They had Grant's ear and became the principal instruments for his peace policy. During 1869–1885, they served as appointed agents on numerous reservations and superintendencies in a mission centered on moral uplift and manual training. Their ultimate goal of acculturating the Indians to American culture was not reached because of frontier land hunger and Congressional patronage politics.

Many other denominations volunteered to help. In 1871, John H. Stout, sponsored by the Dutch Reformed Church, was sent to the Pima reservation in Arizona to implement the policy. However Congress, the church, and private charities spent less money than was needed; the local whites strongly disliked the Indians; the Pima balked at removal; and Stout was frustrated at every turn.

In Arizona and New Mexico, the Navajo were resettled on reservations and grew rapidly in numbers. The Peace Policy began in 1870 when the Presbyterians took over the reservations. They were frustrated because they did not understand the Navajo. However, the Navajo not only gave up raiding but soon became successful at sheep ranching.

The peace policy did not fully apply to the Indian tribes that had supported the Confederacy. They lost much of their land as the United States began to confiscate the western portions of the Indian Territory and began to resettle the Indians there on smaller reservations.

Reaction to the massacre of Lt. Col. George Custer's unit at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876 was shock and dismay at the failure of the Peace Policy. The Indian appropriations measure of August 1876 marked the end of Grant's Peace Policy. The Sioux were given the choice of either selling their lands in the Black Hills for cash or not receiving government gifts of food and other supplies.

Code of Indian Offenses

In 1882, Interior Secretary Henry M. Teller called attention to the "great hindrance" of Indian customs to the progress of assimilation. The resultant "Code of Indian Offenses" in 1883 outlined the procedure for suppressing "evil practice."

A Court of Indian Offenses, consisting of three Indians appointed by the Indian Agent, was to be established at each Indian agency. The Court would serve as judges to punish offenders. Outlawed behavior included participation in traditional dances and feasts, polygamy, reciprocal gift giving and funeral practices, and intoxication or sale of liquor. Also prohibited were "medicine men" who "use any of the arts of the conjurer to prevent the Indians from abandoning their heathenish rites and customs." The penalties prescribed for violations ranged from 10 to 90 days imprisonment and loss of government-provided rations for up to 30 days.

The Five Civilized Tribes were exempt from the Code which remained in effect until 1933.

In implementation on reservations by Indian judges, the Court of Indian Offenses became mostly an institution to punish minor crimes. The 1890 report of the Secretary of the Interior lists the activities of the Court on several reservations and apparently no Indian was prosecuted for dances or "heathenish ceremonies." Significantly, 1890 was the year of the Ghost Dance, ending with the Wounded Knee Massacre.

The role of the Supreme Court in assimilation

In 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney expressed that since Native Americans were "free and independent people" that they could become U.S. citizens. Taney asserted that Native Americans could be naturalized and join the "political community" of the United States.

[Native Americans], without doubt, like the subjects of any other foreign Government, be naturalized by the authority of Congress, and become citizens of a State, and of the United States; and if an individual should leave his nation or tribe, and take up his abode among the white population, he would be entitled to all the rights and privileges which would belong to an emigrant from any other foreign people.

— Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, 1857, What was Taney thinking? American Indian Citizenship in the era of Dred Scott, Frederick E. Hoxie, April 2007.

The political ideas during the time of assimilation policy are known by many Indians as the progressive era, but more commonly known as the assimilation era) The progressive era was characterized by a resolve to emphasize the importance of dignity and independence in the modern industrialized world. This idea is applied to Native Americans in a quote from Indian Affairs Commissioner John Oberly: "[The Native American] must be imbued with the exalting egotism of American civilization so that he will say ‘I’ instead of ‘We’, and ‘This is mine’ instead of ‘This is ours’." Progressives also had faith in the knowledge of experts. This was a dangerous idea to have when an emerging science was concerned with ranking races based on moral capabilities and intelligence. Indeed, the idea of an inferior Indian race made it into the courts. The progressive era thinkers also wanted to look beyond legal definitions of equality to create a realistic concept of fairness. Such a concept was thought to include a reasonable income, decent working conditions, as well as health and leisure for every American. These ideas can be seen in the decisions of the Supreme Court during the assimilation era.

Cases such as Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, Talton v. Mayes, Winters v. United States, United States v. Winans, United States v. Nice, and United States v. Sandoval provide excellent examples of the implementation of the paternal view of Native Americans as they refer back to the idea of Indians as "wards of the nation". Some other issues that came into play were the hunting and fishing rights of the natives, especially when land beyond theirs affected their own practices, whether or not Constitutional rights necessarily applied to Indians, and whether tribal governments had the power to establish their own laws. As new legislation tried to force the American Indians into becoming just Americans, the Supreme Court provided these critical decisions. Native American nations were labeled "domestic dependent nations" by Marshall in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, one of the first landmark cases involving Indians. Some decisions focused more on the dependency of the tribes, while others preserved tribal sovereignty, while still others sometimes managed to do both.

Decisions focusing on dependence

United States vs. Kagama

The United States Supreme Court case United States v. Kagama (1886) set the stage for the court to make even more powerful decisions based on plenary power. To summarize congressional plenary power, the court stated:

The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful, now weak and diminished in numbers, is necessary to their protection, as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell. It must exist in that government, because it never has existed anywhere else; because the theater of its exercise is within the geographical limits of the United [118 U.S. 375, 385] States; because it has never been denied; and because it alone can enforce its laws on all the tribes.

The decision in United States v. Kagama led to the new idea that "protection" of Native Americans could justify intrusion into intratribal affairs. The Supreme Court and Congress were given unlimited authority with which to force assimilation and acculturation of Native Americans into American society.

United States v. Nice

During the years leading up to passage of the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, United States v. Nice (1916), was a result of the idea of barring American Indians from the sale of liquor. The United States Supreme Court case overruled a decision made eleven years before, Matter of Heff, 197 U.S. 48 (1905), which allowed American Indian U.S. citizens to drink liquor. The quick reversal shows how law concerning American Indians often shifted with the changing governmental and popular views of American Indian tribes. The US Congress continued to prohibit the sale of liquor to American Indians. While many tribal governments had long prohibited the sale of alcohol on their reservations, the ruling implied that American Indian nations could not be entirely independent, and needed a guardian for protection.

United States v. Sandoval

Like United States v. Nice, the United States Supreme Court case of United States v. Sandoval (1913) rose from efforts to bar American Indians from the sale of liquor. As American Indians were granted citizenship, there was an effort to retain the ability to protect them as a group which was distinct from regular citizens. The Sandoval Act reversed the U.S. v. Joseph decision of 1876, which claimed that the Pueblo were not considered federal Indians. The 1913 ruling claimed that the Pueblo were "not beyond the range of congressional power under the Constitution". This case resulted in Congress continuing to prohibit the sale of liquor to American Indians. The ruling continued to suggest that American Indians needed protection.

Decisions focusing on sovereignty

There were several United States Supreme Court cases during the assimilation era that focused on the sovereignty of American Indian nations. These cases were extremely important in setting precedents for later cases and for legislation dealing with the sovereignty of American Indian nations.

Ex parte Crow Dog (1883)

Ex parte Crow Dog was a US Supreme Court appeal by an Indian who had been found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. The defendant was an American Indian who had been found guilty of the murder of another American Indian. Crow Dog argued that the district court did not have the jurisdiction to try him for a crime committed between two American Indians that happened on an American Indian reservation. The court found that although the reservation was located within the territory covered by the district court's jurisdiction, Rev. Stat. § 2146 precluded the inmate's indictment in the district court. Section 2146 stated that Rev. Stat. § 2145, which made the criminal laws of the United States applicable to Indian country, did not apply to crimes committed by one Indian against another, or to crimes for which an Indian was already punished by the law of his tribe. The Court issued the writs of habeas corpus and certiorari to the Indian.

Talton v. Mayes (1896)

The United States Supreme Court case of Talton v. Mayes was a decision respecting the authority of tribal governments. This case decided that the individual rights protections, specifically the Fifth Amendment, which limit federal, and later, state governments, do not apply to tribal government. It reaffirmed earlier decisions, such as the 1831 Cherokee Nation v. Georgia case, that gave Indian tribes the status of "domestic dependent nations", the sovereignty of which is independent of the federal government. Talton v. Mayes is also a case dealing with Native American dependence, as it deliberated over and upheld the concept of congressional plenary authority. This part of the decision led to some important pieces of legislation concerning Native Americans, the most important of which is the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Good Shot v. United States (1900)

This United States Supreme Court case occurred when an American Indian shot and killed a non-Indian. The question arose of whether or not the United States Supreme Court had jurisdiction over this issue. In an effort to argue against the Supreme Court having jurisdiction over the proceedings, the defendant filed a petition seeking a writ of certiorari. This request for judicial review, upon writ of error, was denied. The court held that a conviction for murder, punishable with death, was no less a conviction for a capital crime by reason even taking into account the fact that the jury qualified the punishment. The American Indian defendant was sentenced to life in prison.

Montoya v. United States (1901)

This United States Supreme court case came about when the surviving partner of the firm of E. Montoya & Sons petitioned against the United States and the Mescalero Apache Indians for the value their livestock which was taken in March 1880. It was believed that the livestock was taken by "Victorio's Band" which was a group of these American Indians. It was argued that the group of American Indians who had taken the livestock were distinct from any other American Indian tribal group, and therefore the Mescalero Apache American Indian tribe should not be held responsible for what had occurred. After the hearing, the Supreme Court held that the judgment made previously in the Court of Claims would not be changed. This is to say that the Mescalero Apache American Indian tribe would not be held accountable for the actions of Victorio's Band. This outcome demonstrates not only the sovereignty of American Indian tribes from the United States, but also their sovereignty from one another. One group of American Indians cannot be held accountable for the actions of another group of American Indians, even though they are all part of the American Indian nation.

US v. Winans (1905)

In this case, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Yakama tribe, reaffirming their prerogative to fish and hunt on off-reservation land. Further, the case established two important principles regarding the interpretation of treaties. First, treaties would be interpreted in the way Indians would have understood them and "as justice and reason demand". Second, the Reserved Rights Doctrine was established which states that treaties are not rights granted to the Indians, but rather "a reservation by the Indians of rights already possessed and not granted away by them". These "reserved" rights, meaning never having been transferred to the United States or any other sovereign, include property rights, which include the rights to fish, hunt and gather, and political rights. Political rights reserved to the Indian nations include the power to regulate domestic relations, tax, administer justice, or exercise civil and criminal jurisdiction.

Winters v. United States (1908)

The United States Supreme Court case Winters v. United States was a case primarily dealing with water rights of American Indian reservations. This case clarified what water sources American Indian tribes had "implied" rights to put to use. This case dealt with the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation and their right to utilize the water source of the Milk River in Montana. The reservation had been created without clearly stating the explicit water rights that the Fort Belknap American Indian reservation had. This became a problem once non-Indian settlers began moving into the area and using the Milk River as a water source for their settlements. As water sources are extremely sparse and limited in Montana, this argument of who had the legal rights to use the water was presented. After the case was tried, the Supreme Court came to the decision that the Fort Belknap reservation had reserved water rights through the 1888 agreement which had created the American Indian Reservation in the first place. This case was very important in setting a precedent for cases after the assimilation era. It was used as a precedent for the cases Arizona v. California, Tulee v. Washington, Washington v. McCoy, Nevada v. United States, Cappaert v. United States, Colorado River Water Conservation Dist. v. United States, United States v. New Mexico, and Arizona v. San Carlos Apache Tribe of Arizona which all focused on the sovereignty of American Indian tribes.

Choate v. Trapp (1912)

As more Native Americans received allotments through the Dawes Act, there was a great deal of public and state pressure to tax allottees. However, in the United States Supreme court case Choate v. Trapp, 224 U.S. 665 (1912), the court ruled for Indian allottees to be exempt from state taxation.

Clairmont v. United States (1912)

This United States Supreme Court case resulted when a defendant appealed the decision on his case. The defendant filed a writ of error to obtain review of his conviction after being convicted of unlawfully introducing intoxicating liquor into an American Indian reservation. This act was found a violation of the Act of Congress of January 30, 1897, ch. 109, 29 Stat. 506. The defendant's appeal stated that the district court lacked jurisdiction because the offense for which he was convicted did not occur in American Indian country. The defendant had been arrested while traveling on a train that had just crossed over from American Indian country. The defendant's argument held and the Supreme Court reversed the defendant's conviction remanding the cause to the district court with directions to quash the indictment and discharge the defendant.

United States v. Quiver (1916)

This case was sent to the United States Supreme Court after first appearing in a district court in South Dakota. The case dealt with adultery committed on a Sioux Indian reservation. The district court had held that adultery committed by an Indian with another Indian on an Indian reservation was not punishable under the act of March 3, 1887, c. 397, 24 Stat. 635, now § 316 of the Penal Code. This decision was made because the offense occurred on a Sioux Indian reservation which is not said to be under jurisdiction of the district court. The United States Supreme Court affirmed the judgment of the district court saying that the adultery was not punishable as it had occurred between two American Indians on an American Indian reservation.

Native American education and boarding schools

Non-reservation boarding schools

In 1634, Fr. Andrew White of the Jesuits established a mission in what is now the state of Maryland, and the purpose of the mission, stated through an interpreter to the chief of an Indian tribe there, was "to extend civilization and instruction to his ignorant race, and show them the way to heaven". The mission's annual records report that by 1640, a community had been founded which they named St. Mary's, and the Indians were sending their children there to be educated. This included the daughter of the Pascatoe Indian chief Tayac, which suggests not only a school for Indians, but either a school for girls, or an early co-ed school. The same records report that in 1677, "a school for humanities was opened by our Society in the centre of [Maryland], directed by two of the Fathers; and the native youth, applying themselves assiduously to study, made good progress. Maryland and the recently established school sent two boys to St. Omer who yielded in abilities to few Europeans, when competing for the honour of being first in their class. So that not gold, nor silver, nor the other products of the earth alone, but men also are gathered from thence to bring those regions, which foreigners have unjustly called ferocious, to a higher state of virtue and cultivation."

In 1727, the Sisters of the Order of Saint Ursula founded Ursuline Academy in New Orleans, which is currently the oldest, continuously-operating school for girls and the oldest Catholic school in the United States. From the time of its foundation it offered the first classes for Native American girls, and would later offer classes for female African-American slaves and free women of color.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School founded by Richard Henry Pratt in 1879 was the first Indian boarding school established. Pratt was encouraged by the progress of Native Americans whom he had supervised as prisoners in Florida, where they had received basic education. When released, several were sponsored by American church groups to attend institutions such as Hampton Institute. He believed education was the means to bring American Indians into society.

Pratt professed "assimilation through total immersion". Because he had seen men educated at schools like Hampton Institute become educated and assimilated, he believed the principles could be extended to Indian children. Immersing them in the larger culture would help them adapt. In addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic, the Carlisle curriculum was modeled on the many industrial schools: it constituted vocational training for boys and domestic science for girls, in expectation of their opportunities on the reservations, including chores around the school and producing goods for market. In the summer, students were assigned to local farms and townspeople for boarding and to continue their immersion. They also provided labor at low cost, at a time when many children earned pay for their families.

Carlisle and its curriculum became the model for schools sponsored by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. By 1902 there were twenty-five federally funded non-reservation schools across fifteen states and territories with a total enrollment of over 6,000. Although federal legislation made education compulsory for Native Americans, removing students from reservations required parental authorization. Officials coerced parents into releasing a quota of students from any given reservation.

Once the new students arrived at the boarding schools, their lives altered drastically. They were usually given new haircuts, uniforms of European-American style clothes, and even new English names, sometimes based on their own, other times assigned at random. They could no longer speak their own languages, even with each other. They were expected to attend Christian churches. Their lives were run by the strict orders of their teachers, and it often included grueling chores and stiff punishments.

Additionally, infectious disease was widespread in society, and often swept through the schools. This was due to lack of information about causes and prevention, inadequate sanitation, insufficient funding for meals, overcrowded conditions, and students whose resistance was low.

An Indian boarding school was one of many schools that were established in the United States during the late 19th century to educate Native American youths according to American standards. In some areas, these schools were primarily run by missionaries. Especially given the young age of some of the children sent to the schools, they have been documented as traumatic experiences for many of the children who attended them. They were generally forbidden to speak their native languages, taught Christianity instead of their native religions, and in numerous other ways forced to abandon their Indian identity and adopt American culture. Many cases of mental and sexual abuse have been documented, as in North Dakota. Little recognition to the drastic change in life of the younger children was evident in the forced federal rulings for compulsory schooling and sometimes harsh interpretation in methods of gathering, even to intruding in the Indian homes. This proved extremely stressful to those who lived in the remote desert of Arizona on the Hopi Mesas well isolated from the American culture. Separation and boarding school living would last several years. It remains today, a topic in traditional Hopi Indian recitations of their history—the traumatic situation and resistance to government edicts for forced schooling. Conservatives in the village of Oraibi opposed sending their young children to the Government school located in Keams Canyon. It was far enough away to require full time boarding for at least each school year. At the closing of the nineteenth century, the Hopi were for the most part a walking society. Unfortunately, visits between family and the schooled children were impossible. As a result, children were hidden to prevent forced collection by the U.S. military. Wisely, the Indian Agent, Leo Crane requested the military troop to remain in the background while he and his helpers searched and gathered the youngsters for their multi-day travel by military wagon and year-long separation from their family. By 1923 in the Northwest, most Indian schools had closed and Indian students were attending public schools. States took on increasing responsibility for their education. Other studies suggest attendance in some Indian boarding schools grew in areas of the United States throughout the first half of the 20th century, doubling from 1900 to the 1960s. Enrollment reached its highest point in the 1970s. In 1973, 60,000 American Indian children were estimated to have been enrolled in an Indian boarding school. In 1976, the Tobeluk vs Lind case was brought by teenage Native Alaskan plaintiffs against the State of Alaska alleging that the public school situation was still an unequal one.

The Meriam Report of 1928

The Meriam Report, officially titled "The Problem of Indian Administration", was prepared for the Department of Interior. Assessments found the schools to be underfunded and understaffed, too heavily institutionalized, and run too rigidly. What had started as an idealistic program about education had gotten subverted.

It recommended:

- abolishing the "Uniform Course of Study", which taught only majority American cultural values;

- having younger children attend community schools near home, though older children should be able to attend non-reservation schools; and

- ensuring that the Indian Service provided Native Americans with the skills and education to adapt both in their own traditional communities (which tended to be more rural) and the larger American society.

Indian New Deal

John Collier, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1933–1945, set the priorities of the New Deal policies toward Native Americans, with an emphasis on reversing as much of the assimilationist policy as he could. Collier was instrumental in ending the loss of reservations lands held by Indians, and in enabling many tribal nations to re-institute self-government and preserve their traditional culture. Some Indian tribes rejected the unwarranted outside interference with their own political systems the new approach had brought them.

Collier's 1920– 1922 visit to Taos Pueblo had a lasting impression on Collier. He now saw the Indian world as morally superior to American society, which he considered to be "physically, religiously, socially, and aesthetically shattered, dismembered, directionless". Collier came under attack for his romantic views about the moral superiority of traditional society as opposed to modernity. Philp says after his experience at the Taos Pueblo, Collier "made a lifelong commitment to preserve tribal community life because it offered a cultural alternative to modernity. ... His romantic stereotyping of Indians often did not fit the reality of contemporary tribal life."

Collier carried through the Indian New Deal with Congress' passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. It was one of the most influential and lasting pieces of legislation relating to federal Indian policy. Also known as the Wheeler–Howard Act, this legislation reversed fifty years of assimilation policies by emphasizing Indian self-determination and a return of communal Indian land, which was in direct contrast with the objectives of the Indian General Allotment Act of 1887.

Collier was also responsible for getting the Johnson–O'Malley Act passed in 1934, which allowed the Secretary of the Interior to sign contracts with state governments to subsidize public schooling, medical care, and other services for Indians who did not live on reservations. The act was effective only in Minnesota.

Collier's support of the Navajo Livestock Reduction program resulted in Navajo opposition to the Indian New Deal. The Indian Rights Association denounced Collier as a "dictator" and accused him of a "near reign of terror" on the Navajo reservation. According to historian Brian Dippie, "(Collier) became an object of 'burning hatred' among the very people whose problems so preoccupied him."

Change to community schools

Several events in the late 1960s and mid-1970s (Kennedy Report, National Study of American Indian Education, Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975) led to renewed emphasis on community schools. Many large Indian boarding schools closed in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 2007, 9,500 American Indian children lived in an Indian boarding school dormitory. From 1879 when the Carlisle Indian School was founded to the present day, more than 100,000 American Indians are estimated to have attended an Indian boarding school.

A similar system in Canada was known as the Canadian residential school system.

Lasting effects of the Americanization policy

While the concerted effort to assimilate Native Americans into American culture was abandoned officially, integration of Native American tribes and individuals continues to the present day. Often Native Americans are perceived as having been assimilated. However, some Native Americans feel a particular sense of being from another society or do not belong in a primarily "white" European majority society, despite efforts to socially integrate them.

In the mid-20th century, as efforts were still under way for assimilation, some studies treated American Indians simply as another ethnic minority, rather than citizens of semi-sovereign entities which they are entitled to by treaty. The following quote from the May 1957 issue of Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, shows this:

The place of Indians in American society may be seen as one aspect of the question of the integration of minority groups into the social system.

Since the 1960s, however, there have been major changes in society. Included is a broader appreciation for the pluralistic nature of United States society and its many ethnic groups, as well as for the special status of Native American nations. More recent legislation to protect Native American religious practices, for instance, points to major changes in government policy. Similarly the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 was another recognition of the special nature of Native American culture and federal responsibility to protect it.

As of 2013, "Montana is the only state in the U.S. with a constitutional mandate to teach American Indian history, culture, and heritage to preschool through higher education students via the Indian Education for All Act."[62] The "Indian Education for All" curriculum, created by the Montana Office of Public Instruction, is distributed online for primary and secondary schools.

Modern cultural and linguistic preservation

To evade a shift to English, some Native American tribes have initiated language immersion schools for children, where a native Indian language is the medium of instruction. For example, the Cherokee Nation instigated a 10-year language preservation plan that involved growing new fluent speakers of the Cherokee language from childhood on up through school immersion programs as well as a collaborative community effort to continue to use the language at home. This plan was part of an ambitious goal that in 50 years, 80% or more of the Cherokee people will be fluent in the language. The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $3 million into opening schools, training teachers, and developing curricula for language education, as well as initiating community gatherings where the language can be actively used. Formed in 2006, the Kituwah Preservation & Education Program (KPEP) on the Qualla Boundary focuses on language immersion programs for children from birth to fifth grade, developing cultural resources for the general public and community language programs to foster the Cherokee language among adults.

There is also a Cherokee language immersion school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma that educates students from pre-school through eighth grade. Because Oklahoma's official language is English, Cherokee immersion students are hindered when taking state-mandated tests because they have little competence in English. The Department of Education of Oklahoma said that in 2012 state tests: 11% of the school's sixth-graders showed proficiency in math, and 25% showed proficiency in reading; 31% of the seventh-graders showed proficiency in math, and 87% showed proficiency in reading; 50% of the eighth-graders showed proficiency in math, and 78% showed proficiency in reading. The Oklahoma Department of Education listed the charter school as a Targeted Intervention school, meaning the school was identified as a low-performing school but has not so that it was a Priority School. Ultimately, the school made a C, or a 2.33 grade point average on the state's A–F report card system. The report card shows the school getting an F in mathematics achievement and mathematics growth, a C in social studies achievement, a D in reading achievement, and an A in reading growth and student attendance. "The C we made is tremendous," said school principal Holly Davis, "[t]here is no English instruction in our school's younger grades, and we gave them this test in English." She said she had anticipated the low grade because it was the school's first year as a state-funded charter school, and many students had difficulty with English. Eighth graders who graduate from the Tahlequah immersion school are fluent speakers of the language, and they usually go on to attend Sequoyah High School where classes are taught in both English and Cherokee.