From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blasphemy

Blasphemy is a speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a religious crime, especially the Abrahamic religions, including the speaking the "sacred name" in Judaism and the "eternal sin" in Christianity.

In the early history of the Church heresy received more attention than blasphemy because it was considered a more serious threat to Orthodoxy. Blasphemy was often regarded as an isolated offense wherein the faithful lapsed momentarily from the expected standard of conduct. When iconoclasm and the fundamental understanding of the sacred became more contentious matters during the Reformation, blasphemy was treated similar to heresy, and accusations of blasphemy were made not only against people who made off-the-cuff profane remarks while drunk, but against those types of persons who espoused unorthodox ideas that religious officials considered dangerous.

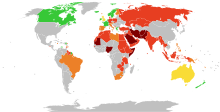

Blasphemy laws were abolished in England and Wales in 2008, and in Ireland in 2020. Scotland repealed its blasphemy laws in 2021. Many other countries have abolished blasphemy laws including Denmark, the Netherlands, Iceland, Norway and New Zealand. As of 2019, 40 percent of the world's countries still had blasphemy laws on the books, including 18 countries in the Middle East and North Africa, or 90% of countries in that region. Dharmic religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, have no concept of blasphemy and hence prescribe no punishment.

Etymology

The word "blasphemy" came via Middle English blasfemen and Old French blasfemer and Late Latin blasphemare from Greek βλασφημέω, from βλασ, "injure" and φήμη, "utterance, talk, speech". From blasphemare also came Old French blasmer, from which the English word "blame" came. Blasphemy: 'from Gk. blasphemia "a speaking ill, impious speech, slander," from blasphemein "to speak evil of." "In the sense of speaking evil of God this word is found in Ps. 74:18; Isa. 52:5; Rom. 2:24; Rev. 13:1, 6; 16:9, 11, 21. It denotes also any kind of calumny, or evil-speaking, or abuse (1 Kings 21:10 LXX; Acts 13:45; 18:6, etc.)."

History

Heresy received more attention than blasphemy throughout the Middle Ages because it was considered a more serious threat to Orthodoxy, while blasphemy was mostly seen as irreverent remarks made by persons who may have been drunk or diverged from good standards of conduct in what was treated as isolated incidents of misbehavior. When iconoclasm and the fundamental understanding of the sacred became more contentious matters during the Reformation, blasphemy started to be regarded as similar to heresy.

In The Whole Duty of Man (sometimes attributed to Richard Allestree or John Fell) blasphemy is described as "speaking any evil Thing of God":

...the highest Degree whereof is cursing him; or if we do not speak it with our Mouths, yet if we do it in our Hearts, by thinking any unworthy Thing of him, it is look'd on by God, who sees the Heart, as the vilest Dishonour.

The intellectual culture of the early English Englightenment had embraced ironic or scoffing tones in contradistinction to the idea of sacredness in revealed religion. The characterization of "scoffing" as blasphemy was defined as profaning the Scripture by irreverent "Buffoonery and Banter". From at least the 18th century on, the clergy of the Church of England justified blasphemy prosecutions by distinguishing "sober reasoning" from mockery and scoffing. Religious doctrine could be discussed "in a calm, decent and serious way" (in the words of Bishop Gibson) but mockery and scoffing, they said, were appeals to sentiment, not to reason.

In Whitehouse v. Lemon (1976), the last blasphemy prosecution heard by English courts, the court repeated what had by then become a textbook standard for blasphemy cases:

It is not blasphemous to speak or publish opinions hostile to the Christian religion, or to deny the existence of God, if the publication is couched in decent and temperate language. The test to be applied is as to the manner in which the doctrines are advocated and not as to the substance of the doctrines themselves.

By religion

Christianity

Christian theology condemns blasphemy. "Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain", one of the Ten Commandments, forbids blasphemy, which Christians regard as "an affront to God's holiness". Leviticus 24:16 states that "anyone who blasphemes the name of Yahweh will be put to death". In Mark 3:29, blaspheming the Holy Spirit is spoken of as unforgivable—an eternal sin.

In 2 Kings 18, the Rabshakeh gave the word from the king of Assyria, dissuading trust in the Lord, asserting that God is no more able to deliver than other deities of the land.

In Matthew 9:2–3, Jesus told a paralytic "your sins are forgiven" and was accused of blasphemy.

Blasphemy has been condemned as a serious sin by the major creeds and Church theologians, along with apostasy and infidelity [unbelief], cf. Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologiae.

- Thomas Aquinas says that "[if] we compare murder and blasphemy as regards the objects of those sins, it is clear that blasphemy, which is a sin committed directly against God, is more grave than murder, which is a sin against one's neighbor. On the other hand, if we compare them in respect of the harm wrought by them, murder is the graver sin, for murder does more harm to one's neighbor, than blasphemy does to God".

- The Book of Concord calls blasphemy "the greatest sin that can be outwardly committed".

- The Baptist Confession of Faith says: "Therefore, to swear vainly or rashly by the glorious and awesome name of God…is sinful, and to be regarded with disgust and detestation. …For by rash, false, and vain oaths, the Lord is provoked and because of them this land mourns".

- The Heidelberg Catechism answers question 100 about blasphemy by stating that "no sin is greater or provokes God's wrath more than the blaspheming of His Name".

- The Westminster Larger Catechism explains that "The sins forbidden in the third commandment are, the abuse of it in an ignorant, vain, irreverent, profane...mentioning...by blasphemy...to profane jests, ...vain janglings, ...to charms or sinful lusts and practices".

- Calvin found it intolerable "when a person is accused of blasphemy, to lay the blame on the ebullition of passion, as if God were to endure the penalty whenever we are provoked".

Catholic prayers and reparations for blasphemy

In the Catholic Church, there are specific prayers and devotions as Acts of Reparation for blasphemy. For instance, The Golden Arrow Holy Face Devotion (Prayer) first introduced by Sister Marie of St Peter in 1844 is recited "in a spirit of reparation for blasphemy". This devotion (started by Sister Marie and then promoted by the Venerable Leo Dupont) was approved by Pope Leo XIII in 1885. The Raccoltabook includes a number of such prayers. The Five First Saturdays devotions are done with the intention in the heart of making reparation to the Blessed Mother for blasphemies against her, her name and her holy initiatives.

The Holy See has specific "Pontifical organizations" for the purpose of the reparation of blasphemy through Acts of Reparation to Jesus Christ, e.g. the Pontifical Congregation of the Benedictine Sisters of the Reparation of the Holy Face.

Punishment

In 1636, the Puritan controlled Massachusetts Bay Colony made blasphemy – defined as "a cursing of God by atheism, or the like" – punishable by death. The last person hanged for blasphemy in Great Britain was Thomas Aikenhead aged 20, in Scotland in 1697. He was prosecuted for denying the veracity of the Old Testament and the legitimacy of Christ's miracles.

In England, under common law, blasphemy came to be punishable by fine, imprisonment or corporal punishment. Blackstone, in his commentaries, described the offence as,

Denying the being of God, contumelious reproaches of our Saviour Christ, profane scoffing at the Holy scripture, or exposing it to contempt or ridicule.

Blasphemy (and blasphemous libel) remained a criminal offence in England & Wales until 2008. In the 18th and 19th centuries, this meant that promoting atheism could be a crime and was vigorously prosecuted. It was last successfully prosecuted in the case of Whitehouse v Lemon (1977), where the defendant was fined £500 and given a nine-month suspended prison sentence (the publisher was also fined £1,000). It ended with the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 which abolished the common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel.

Disputation of Paris

During the Middle Ages a series of debates on Judaism were staged by the Catholic Church, including the Disputation of Paris (1240), the Disputation of Barcelona (1263), and Disputation of Tortosa (1413–14), and during those disputations, Jewish converts to Christianity, such as Nicholas Donin (in Paris) and Pablo Christiani (in Barcelona) claimed the Talmud contained insulting references to Jesus.

The Disputation of Paris, also known as the Trial of the Talmud, took place in 1240 at the court of the reigning king of France, Louis IX (St. Louis). It followed the work of Nicholas Donin, a Jewish convert to Christianity, who translated the Talmud and pressed 35 charges against it to Pope Gregory IX by quoting a series of alleged blasphemous passages about Jesus, Mary or Christianity. Four rabbis defended the Talmud against Donin's accusations. A commission of Christian theologians condemned the Talmud to be burned and on 17 June 1244, twenty-four carriage loads of Jewish religious manuscripts were set on fire in the streets of Paris. The translation of the Talmud from Hebrew to non-Jewish languages stripped Jewish discourse from its covering, something that was resented by Jews as a profound violation.

Between 1239 and 1775, the Roman Catholic Church at various times either forced the censoring of parts of the Talmud that it considered theologically problematic or the destruction of copies of the Talmud.

Islam

Punishment and definition

Blasphemy in Islam is impious utterance or action concerning God, Muhammad or anything considered sacred in Islam. The Quran admonishes blasphemy, but does not specify any worldly punishment for blasphemy. The hadiths, which are another source of Sharia, suggest various punishments for blasphemy, which may include death. However, it has been argued that the death penalty applies only to cases where there is treason involved that may seriously harm the Muslim community, especially during times of war. Different traditional schools of jurisprudence prescribe different punishment for blasphemy, depending on whether the blasphemer is Muslim or non-Muslim, a man or a woman. In the modern Muslim world, the laws pertaining to blasphemy vary by country, and some countries prescribe punishments consisting of fines, imprisonment, flogging, hanging, or beheading. Blasphemy laws were rarely enforced in pre-modern Islamic societies, but in the modern era some states and radical groups have used charges of blasphemy in an effort to burnish their religious credentials and gain popular support at the expense of liberal Muslim intellectuals and religious minorities. In recent years, accusations of blasphemy against Islam have sparked international controversies and played part in incidents of mob violence and assassinations of prominent figures.

Failed OIC anti-blasphemy campaign at UN

The campaign for worldwide criminal penalties for the "defamation of religions" had been spearheaded by Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) on behalf of the United Nations' large Muslim bloc. The campaign ended in 2011 when the proposal was withdrawn in Geneva, in the Human Rights Council because of lack of support, marking an end to the effort to establish worldwide blasphemy strictures along the lines of those in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. This resolution had passed every year since 1999, in the United Nations, with declining number of "yes" votes with each successive year. In the early 21st century, blasphemy became an issue in the United Nations (UN). The United Nations passed several resolutions which called upon the world to take action against the "defamation of religions". However, in July 2011, the UN Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) released a 52-paragraph statement which affirmed the freedom of speech and rejected the laws banning "display of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system'.

Judaism

In Leviticus 24:16 the punishment for blasphemy is death. In Jewish law the only form of blasphemy which is punishable by death is blaspheming the name of the Lord.

The Seven Laws of Noah, which Judaism sees as applicable to all people, prohibit blasphemy.

In one of the texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls, called the Damascus Document, violence against non-Jews (also called Gentiles) is prohibited, except in cases where it is sanctioned by a Jewish governing authority "so that they will not blaspheme".

Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism

Indian-origin religions (also called Dharma religions), Hinduism and its contemporary Buddhism and Jainism, have no concept of blasphemy. It is an alien concept in Indian-origin theology and culture. In contrast, in West Asia, the birthplace of Abrahamic religions (namely Islam, Judaism and Christianity), there was no room for such tolerance and respect for dissent where heretics and blasphemers had to pay with their lives. Nāstika, meaning atheist or atheism, is a valid and accepted stream of Indian origin religions where Buddhism, Jainism, as well as Cārvāka, Ajñana and Ājīvika are considered atheist schools of philosophy.

Sikhism

Blasphemy is considered as the submission to the vanity of the Five inner thieves and especially excessive egoistical pride. According to the Sri Guru Granth Sahib 1st (832/5/2708), "He is a swine, a dog, a donkey, a cat, a beast, a filthy one, a mean man and a pariah (outcaste), who turns his face away from the Guru." Guru Granth Sahib, Page 1381-70-71 contains, "Fareed: O faithless dog, this is not a good way of life. You never come to the mosque for your five daily prayers. Rise up, Fareed, and cleanse yourself; chant your morning prayer. The head which does not bow to the Lord – chop off and remove that head." In the Guru Granth Sahib, page 89–2 contains, "Chop off that head which does not bow to the Lord. O Nanak, that human body, in which there is no pain of separation from the Lord-let that be to the flames." Further in the Guru Granth Sahib page 719 contains, "Even if someone slanders the Lord's humble servant, he does not give up his own goodness."

Backlash against anti–blasphemy laws

Affirmation of Freedom of Speech (FOS)

Multilateral global institutes, such as the Council of Europe and UN, have rejected the imposition of "anti-blasphemy laws" (ABL) and have affirmed the freedom of speech.

The Council of Europe's rejection of ABL and affirmation of FOS

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, after deliberating on the issue of blasphemy law passed the resolution that blasphemy should not be a criminal offence, which was adopted on 29 June 2007 in the "Recommendation 1805 (2007) on blasphemy, religious insults and hate speech against persons on grounds of their religion". This Recommendation set a number of guidelines for member states of the Council of Europe in view of Articles 10 (freedom of expression) and 9 (freedom of thought, conscience and religion) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

UN's rejection of ABL and affirmation of FOS

After OIC's (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) campaign at UN (United Nations) seeking impose of punishment for "defamation of religions" was withdrawn due to consistently dwindling support for their campaign, the UN Human Rights Committee (UNHRC), in July 2011, released a 52-paragraph statement which affirmed the freedom of speech and rejected the laws banning "display of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system'. UNHRC's "General Comment 34 - Paragraph 48" on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) 1976, concerning freedoms of opinion and expression states:

Prohibitions of displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws, are incompatible with the Covenant, except in the specific circumstances envisaged in article 20, paragraph 2, of the Covenant. Such prohibitions must also comply with the strict requirements of article 19, paragraph 3, as well as such articles as 2, 5, 17, 18 and 26. Thus, for instance, it would be impermissible for any such laws to discriminate in favor of or against one or certain religions or belief systems, or their adherents over another, or religious believers over non-believers. Nor would it be permissible for such prohibitions to be used to prevent or punish criticism of religious leaders or commentary on religious doctrine and tenets of faith.

International Blasphemy Day

International Blasphemy Day, observed annually on September 30, encourages individuals and groups to openly express criticism of religion and blasphemy laws. It was founded in 2009 by the Center for Inquiry. A student contacted the Center for Inquiry in Amherst, New York to present the idea, which CFI then supported. Ronald Lindsay, president and CEO of the Center for Inquiry, said, regarding Blasphemy Day, "[W]e think religious beliefs should be subject to examination and criticism just as political beliefs are, but we have a taboo on religion", in an interview with CNN.

Events worldwide on the first annual Blasphemy Day in 2009 included an art exhibit in Washington, D.C. and a free speech festival in Los Angeles.

Removal of blasphemy laws by several nations

Other countries have removed bans on blasphemy. France did so in 1881 (this did not extend to Alsace-Moselle region, then part of Germany, after it joined France) to allow freedom of religion and freedom of the press. Blasphemy was abolished or repealed in Sweden in 1970, England and Wales in 2008, Norway with Acts in 2009 and 2015, the Netherlands in 2014, Iceland in 2015, France for its Alsace-Moselle region in 2016, Malta in 2016, Denmark in 2017, Canada in 2018, New Zealand in 2019, and Ireland in 2020.

Nations with blasphemy laws

In some countries with a state religion, blasphemy is outlawed under the criminal code.

Purpose of blasphemy laws

In some states, blasphemy laws are used to impose the religious beliefs of a majority, while in other countries, they are justified as putatively offering protection of the religious beliefs of minorities. Where blasphemy is banned, it can be either some laws which directly punish religious blasphemy, or some laws that allow those who are offended by blasphemy to punish blasphemers. Those laws may condone penalties or retaliation for blasphemy under the labels of blasphemous libel, expression of opposition, or "vilification," of religion or of some religious practices, religious insult, or hate speech.

Nations with blasphemy laws

As of 2012, 33 countries had some form of anti-blasphemy laws in their legal code. Of these, 21 were Muslim-majority nations – Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, the Maldives, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Turkey, the UAE and Western Sahara. Blasphemy is treated as a capital crime (death penalty) in some Muslim nations. In these nations, such laws have led to the persecution, lynchings, murder or arrest of minorities and dissident members, after flimsy accusations.

The other twelve nations with anti-blasphemy laws in 2012 included India and Singapore, as well as Christian majority states, including Denmark (abolished in 2017), Finland, Germany, Greece (abolished in 2019), Ireland (abolished in 2020), Italy, Malta (abolished in 2016), the Netherlands (abolished in 2014), Nigeria, Norway (abolished in 2015) and Poland. Spain's "offending religious feelings" law is also, effectively, a prohibition on blasphemy. In Denmark, the former blasphemy law which had support of 66% of its citizens in 2012, made it an offence to "mock legal religions and faiths in Denmark". Many Danes saw the "blasphemy law as helping integration because it promotes the acceptance of a multicultural and multi-faith society."

In the judgment E.S. v. Austria (2018), the European Court of Human Rights declined to strike down the blasphemy law in Austria on Article 10 (freedom of speech) grounds, saying that criminalisation of blasphemy could be supported within a state's margin of appreciation. This decision was widely criticised by human rights organisations and commentators both in Europe and North America.

Hyperbolic use of the term blasphemy

In contemporary language, the notion of blasphemy is often used hyperbolically (in a deliberately exaggerated manner). This usage has garnered some interest among linguists recently, and the word blasphemy is a common case used for illustrative purposes.