Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private property, property rights recognition, voluntary exchange, and wage labor. In a market economy, decision-making and investments are determined by owners of wealth, property, or ability to maneuver capital or production ability in capital and financial markets—whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.

Economists, historians, political economists and sociologists have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include laissez-faire or free-market capitalism, anarcho-capitalism, state capitalism and welfare capitalism. Different forms of capitalism feature varying degrees of free markets, public ownership, obstacles to free competition and state-sanctioned social policies. The degree of competition in markets and the role of intervention and regulation as well as the scope of state ownership vary across different models of capitalism. The extent to which different markets are free and the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most of the existing capitalist economies are mixed economies that combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases economic planning.

Market economies have existed under many forms of government and in many different times, places and cultures. Modern capitalist societies developed in Western Europe in a process that led to the Industrial Revolution. Capitalist systems with varying degrees of direct government intervention have since become dominant in the Western world and continue to spread. Economic growth is a characteristic tendency of capitalist economies.

Etymology

The term "capitalist", meaning an owner of capital, appears earlier than the term "capitalism" and dates to the mid-17th century. "Capitalism" is derived from capital, which evolved from capitale, a late Latin word based on caput, meaning "head"—which is also the origin of "chattel" and "cattle" in the sense of movable property (only much later to refer only to livestock). Capitale emerged in the 12th to 13th centuries to refer to funds, stock of merchandise, sum of money or money carrying interest.By 1283, it was used in the sense of the capital assets of a trading firm and was often interchanged with other words—wealth, money, funds, goods, assets, property and so on.

The Hollantse (German: holländische) Mercurius uses "capitalists" in 1633 and 1654 to refer to owners of capital. In French, Étienne Clavier referred to capitalistes in 1788, four years before its first recorded English usage by Arthur Young in his work Travels in France (1792). In his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), David Ricardo referred to "the capitalist" many times. English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge used "capitalist" in his work Table Talk (1823). Pierre-Joseph Proudhon used the term in his first work, What is Property? (1840), to refer to the owners of capital. Benjamin Disraeli used the term in his 1845 work Sybil.

The initial use of the term "capitalism" in its modern sense is attributed to Louis Blanc in 1850 ("What I call 'capitalism' that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others") and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1861 ("Economic and social regime in which capital, the source of income, does not generally belong to those who make it work through their labor"). Karl Marx frequently referred to the "capital" and to the "capitalist mode of production" in Das Kapital (1867). Marx did not use the form capitalism but instead used capital, capitalist and capitalist mode of production, which appear frequently. Due to the word being coined by socialist critics of capitalism, economist and historian Robert Hessen stated that the term "capitalism" itself is a term of disparagement and a misnomer for economic individualism. Bernard Harcourt agrees with the statement that the term is a misnomer, adding that it misleadingly suggests that there is such as a thing as "capital" that inherently functions in certain ways and is governed by stable economic laws of its own.

In the English language, the term "capitalism" first appears, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), in 1854, in the novel The Newcomes by novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, where the word meant "having ownership of capital".[31] Also according to the OED, Carl Adolph Douai, a German American socialist and abolitionist, used the term "private capitalism" in 1863.

History

Capitalism in its modern form can be traced to the emergence of agrarian capitalism and mercantilism in the early Renaissance, in city-states like Florence. Capital has existed incipiently on a small scale for centuries in the form of merchant, renting and lending activities and occasionally as small-scale industry with some wage labor. Simple commodity exchange and consequently simple commodity production, which is the initial basis for the growth of capital from trade, have a very long history. During the Islamic Golden Age, Arabs promulgated capitalist economic policies such as free trade and banking. Their use of Indo-Arabic numerals facilitated bookkeeping. These innovations migrated to Europe through trade partners in cities such as Venice and Pisa. The Italian mathematician Fibonacci traveled the Mediterranean talking to Arab traders and returned to popularize the use of Indo-Arabic numerals in Europe.

Agrarianism

The economic foundations of the feudal agricultural system began to shift substantially in 16th-century England as the manorial system had broken down and land began to become concentrated in the hands of fewer landlords with increasingly large estates. Instead of a serf-based system of labor, workers were increasingly employed as part of a broader and expanding money-based economy. The system put pressure on both landlords and tenants to increase the productivity of agriculture to make profit; the weakened coercive power of the aristocracy to extract peasant surpluses encouraged them to try better methods, and the tenants also had incentive to improve their methods in order to flourish in a competitive labor market. Terms of rent for land were becoming subject to economic market forces rather than to the previous stagnant system of custom and feudal obligation.

Mercantilism

The economic doctrine prevailing from the 16th to the 18th centuries is commonly called mercantilism. This period, the Age of Discovery, was associated with the geographic exploration of foreign lands by merchant traders, especially from England and the Low Countries. Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist methods. Most scholars consider the era of merchant capitalism and mercantilism as the origin of modern capitalism, although Karl Polanyi argued that the hallmark of capitalism is the establishment of generalized markets for what he called the "fictitious commodities", i.e. land, labor and money. Accordingly, he argued that "not until 1834 was a competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that date".

England began a large-scale and integrative approach to mercantilism during the Elizabethan Era (1558–1603). A systematic and coherent explanation of balance of trade was made public through Thomas Mun's argument England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, or the Balance of our Forraign Trade is The Rule of Our Treasure. It was written in the 1620s and published in 1664.

European merchants, backed by state controls, subsidies and monopolies, made most of their profits by buying and selling goods. In the words of Francis Bacon, the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices...".

After the period of the proto-industrialization, the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company, after massive contributions from the Mughal Bengal, inaugurated an expansive era of commerce and trade. These companies were characterized by their colonial and expansionary powers given to them by nation-states. During this era, merchants, who had traded under the previous stage of mercantilism, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a return on investment.

Industrial Revolution

In the mid-18th century a group of economic theorists, led by David Hume (1711–1776) and Adam Smith (1723–1790), challenged fundamental mercantilist doctrines—such as the belief that the world's wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its wealth at the expense of another state.

During the Industrial Revolution, industrialists replaced merchants as a dominant factor in the capitalist system and effected the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of artisans, guilds and journeymen. Also during this period, the surplus generated by the rise of commercial agriculture encouraged increased mechanization of agriculture. Industrial capitalism marked the development of the factory system of manufacturing, characterized by a complex division of labor between and within work process and the routine of work tasks; and eventually established the domination of the capitalist mode of production.

Industrial Britain eventually abandoned the protectionist policy formerly prescribed by mercantilism. In the 19th century, Richard Cobden (1804–1865) and John Bright (1811–1889), who based their beliefs on the Manchester School, initiated a movement to lower tariffs. In the 1840s Britain adopted a less protectionist policy, with the 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws and the 1849 repeal of the Navigation Acts. Britain reduced tariffs and quotas, in line with David Ricardo's advocacy of free trade.

Modernity

Broader processes of globalization carried capitalism across the world. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, a series of loosely connected market systems had come together as a relatively integrated global system, in turn intensifying processes of economic and other globalization. Late in the 20th century, capitalism overcame a challenge by centrally-planned economies and is now the encompassing system worldwide, with the mixed economy as its dominant form in the industrialized Western world.

Industrialization allowed cheap production of household items using economies of scale, while rapid population growth created sustained demand for commodities. The imperialism of the 18th-century decisively shaped globalization in this period.

After the First and Second Opium Wars (1839–1860) and the completion of the British conquest of India, vast populations of Asia became ready consumers of European exports. Also in this period, Europeans colonized areas of sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific islands. The conquest of new parts of the globe, notably sub-Saharan Africa, by Europeans yielded valuable natural resources such as rubber, diamonds and coal and helped fuel trade and investment between the European imperial powers, their colonies and the United States:

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea, the various products of the whole earth, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep. Militarism and imperialism of racial and cultural rivalries were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper. What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man was that age which came to an end in August 1914.

In this period, the global financial system was mainly tied to the gold standard. The United Kingdom first formally adopted this standard in 1821. Soon to follow were Canada in 1853, Newfoundland in 1865, the United States and Germany (de jure) in 1873. New technologies, such as the telegraph, the transatlantic cable, the radiotelephone, the steamship and railways allowed goods and information to move around the world to an unprecedented degree.

In the period following the global depression of the 1930s, governments played an increasingly prominent role in the capitalistic system throughout much of the world.

Contemporary capitalist societies developed in the West from 1950 to the present and this type of system continues to expand throughout different regions of the world—relevant examples started in the United States after the 1950s, France after the 1960s, Spain after the 1970s, Poland after 2015, and others. At this stage capitalist markets are considered developed and are characterized by developed private and public markets for equity and debt, a high standard of living (as characterized by the World Bank and the IMF), large institutional investors and a well-funded banking system. A significant managerial class has emerged and decides on a significant proportion of investments and other decisions. A different future than that envisioned by Marx has started to emerge—explored and described by Anthony Crosland in the United Kingdom in his 1956 book The Future of Socialism and by John Kenneth Galbraith in North America in his 1958 book The Affluent Society, 90 years after Marx's research on the state of capitalism in 1867.

The postwar boom ended in the late 1960s and early 1970s and the economic situation grew worse with the rise of stagflation. Monetarism, a modification of Keynesianism that is more compatible with laissez-faire analyses, gained increasing prominence in the capitalist world, especially under the years in office of Ronald Reagan in the United States (1981–1989) and of Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom (1979–1990). Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called collectivist concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual choice, called "remarketized capitalism".

The end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union allowed for capitalism to become a truly global system in a way not seen since before World War I. The development of the neoliberal global economy would have been impossible without the fall of communism.

Harvard Kennedy School economist Dani Rodrik distinguishes between three historical variants of capitalism:

- Capitalism 1.0 during the 19th century entailed largely unregulated markets with a minimal role for the state (aside from national defense, and protecting property rights)

- Capitalism 2.0 during the post-World War II years entailed Keynesianism, a substantial role for the state in regulating markets, and strong welfare states

- Capitalism 2.1 entailed a combination of unregulated markets, globalization, and various national obligations by states

Relationship to democracy

The relationship between democracy and capitalism is a contentious area in theory and in popular political movements. The extension of adult-male suffrage in 19th-century Britain occurred along with the development of industrial capitalism and representative democracy became widespread at the same time as capitalism, leading capitalists to posit a causal or mutual relationship between them. However, according to some authors in the 20th-century, capitalism also accompanied a variety of political formations quite distinct from liberal democracies, including fascist regimes, absolute monarchies and single-party states. Democratic peace theory asserts that democracies seldom fight other democracies, but critics of that theory suggest that this may be because of political similarity or stability rather than because they are "democratic" or "capitalist". Moderate critics argue that though economic growth under capitalism has led to democracy in the past, it may not do so in the future as authoritarian régimes have been able to manage economic growth using some of capitalism's competitive principles without making concessions to greater political freedom.

Political scientists Torben Iversen and David Soskice see democracy and capitalism as mutually supportive. Robert Dahl argued in On Democracy that capitalism was beneficial for democracy because economic growth and a large middle class were good for democracy. He also argued that a market economy provided a substitute for government control of the economy, which reduces the risks of tyranny and authoritarianism.

In his book The Road to Serfdom (1944), Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992) asserted that the free-market understanding of economic freedom as present in capitalism is a requisite of political freedom. He argued that the market mechanism is the only way of deciding what to produce and how to distribute the items without using coercion. Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan also promoted this view. Friedman claimed that centralized economic operations are always accompanied by political repression. In his view, transactions in a market economy are voluntary and that the wide diversity that voluntary activity permits is a fundamental threat to repressive political leaders and greatly diminishes their power to coerce. Some of Friedman's views were shared by John Maynard Keynes, who believed that capitalism was vital for freedom to survive and thrive. Freedom House, an American think-tank that conducts international research on, and advocates for, democracy, political freedom and human rights, has argued that "there is a high and statistically significant correlation between the level of political freedom as measured by Freedom House and economic freedom as measured by the Wall Street Journal/Heritage Foundation survey".

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013), Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics asserted that inequality is the inevitable consequence of economic growth in a capitalist economy and the resulting concentration of wealth can destabilize democratic societies and undermine the ideals of social justice upon which they are built.

States with capitalistic economic systems have thrived under political regimes deemed to be authoritarian or oppressive. Singapore has a successful open market economy as a result of its competitive, business-friendly climate and robust rule of law. Nonetheless, it often comes under fire for its style of government which, though democratic and consistently one of the least corrupt, operates largely under a one-party rule. Furthermore, it does not vigorously defend freedom of expression as evidenced by its government-regulated press, and its penchant for upholding laws protecting ethnic and religious harmony, judicial dignity and personal reputation. The private (capitalist) sector in the People's Republic of China has grown exponentially and thrived since its inception, despite having an authoritarian government. Augusto Pinochet's rule in Chile led to economic growth and high levels of inequality by using authoritarian means to create a safe environment for investment and capitalism. Similarly, Suharto's authoritarian reign and extirpation of the Communist Party of Indonesia allowed for the expansion of capitalism in Indonesia.

The term "capitalism" in its modern sense is often attributed to Karl Marx. In his Das Kapital, Marx analyzed the "capitalist mode of production" using a method of understanding today known as Marxism. However, Marx himself rarely used the term "capitalism" while it was used twice in the more political interpretations of his work, primarily authored by his collaborator Friedrich Engels. In the 20th century, defenders of the capitalist system often replaced the term "capitalism" with phrases such as free enterprise and private enterprise and replaced "capitalist" with rentier and investor in reaction to the negative connotations associated with capitalism.

Characteristics

In general, capitalism as an economic system and mode of production can be summarized by the following:

- Capital accumulation: production for profit and accumulation as the implicit purpose of all or most of production, constriction or elimination of production formerly carried out on a common social or private household basis.

- Commodity production: production for exchange on a market; to maximize exchange-value instead of use-value.

- Private ownership of the means of production:

- High levels of wage labor.

- The investment of money to make a profit.

- The use of the price mechanism to allocate resources between competing uses.

- Economically efficient use of the factors of production and raw materials due to maximization of value added in the production process.

- Freedom of capitalists to act in their self-interest in managing their business and investments.

Market

In free market and laissez-faire forms of capitalism, markets are used most extensively with minimal or no regulation over the pricing mechanism. In mixed economies, which are almost universal today, markets continue to play a dominant role, but they are regulated to some extent by the state in order to correct market failures, promote social welfare, conserve natural resources, fund defense and public safety or other rationale. In state capitalist systems, markets are relied upon the least, with the state relying heavily on state-owned enterprises or indirect economic planning to accumulate capital.

Competition arises when more than one producer is trying to sell the same or similar products to the same buyers. Adherents of the capitalist theory believe that competition leads to innovation and more affordable prices. Monopolies or cartels can develop, especially if there is no competition. A monopoly occurs when a firm has exclusivity over a market. Hence, the firm can engage in rent seeking behaviors such as limiting output and raising prices because it has no fear of competition. A cartel is a group of firms that act together in a monopolistic manner to control output and prices.

Governments have implemented legislation for the purpose of preventing the creation of monopolies and cartels. In 1890, the Sherman Antitrust Act became the first legislation passed by the United States Congress to limit monopolies.

Wage labor

Wage labor, usually referred to as paid work, paid employment, or paid labor, refers to the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer in which the worker sells their labor power under a formal or informal employment contract. These transactions usually occur in a labor market where wages or salaries are market-determined.

In exchange for the money paid as wages (usual for short-term work-contracts) or salaries (in permanent employment contracts), the work product generally becomes the undifferentiated property of the employer. A wage laborer is a person whose primary means of income is from the selling of their labor in this way.

Profit motive

The profit motive, in the theory of capitalism, is the desire to earn income in the form of profit. Stated differently, the reason for a business's existence is to turn a profit. The profit motive functions according to rational choice theory, or the theory that individuals tend to pursue what is in their own best interests. Accordingly, businesses seek to benefit themselves and/or their shareholders by maximizing profit.

In capitalist theoretics, the profit motive is said to ensure that resources are being allocated efficiently. For instance, Austrian economist Henry Hazlitt explains: "If there is no profit in making an article, it is a sign that the labor and capital devoted to its production are misdirected: the value of the resources that must be used up in making the article is greater than the value of the article itself".

Private property

The relationship between the state, its formal mechanisms, and capitalist societies has been debated in many fields of social and political theory, with active discussion since the 19th century. Hernando de Soto is a contemporary Peruvian economist who has argued that an important characteristic of capitalism is the functioning state protection of property rights in a formal property system where ownership and transactions are clearly recorded.

According to de Soto, this is the process by which physical assets are transformed into capital, which in turn may be used in many more ways and much more efficiently in the market economy. A number of Marxian economists have argued that the Enclosure Acts in England and similar legislation elsewhere were an integral part of capitalist primitive accumulation and that specific legal frameworks of private land ownership have been integral to the development of capitalism.

Private property rights are not absolute, as in many countries the state has the power to seize private property, typically for public use, under the powers of eminent domain.

Market competition

In capitalist economics, market competition is the rivalry among sellers trying to achieve such goals as increasing profits, market share and sales volume by varying the elements of the marketing mix: price, product, distribution and promotion. Merriam-Webster defines competition in business as "the effort of two or more parties acting independently to secure the business of a third party by offering the most favourable terms". It was described by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations (1776) and later economists as allocating productive resources to their most highly valued uses and encouraging efficiency. Smith and other classical economists before Antoine Augustine Cournot were referring to price and non-price rivalry among producers to sell their goods on best terms by bidding of buyers, not necessarily to a large number of sellers nor to a market in final equilibrium. Competition is widespread throughout the market process. It is a condition where "buyers tend to compete with other buyers, and sellers tend to compete with other sellers". In offering goods for exchange, buyers competitively bid to purchase specific quantities of specific goods which are available, or might be available if sellers were to choose to offer such goods. Similarly, sellers bid against other sellers in offering goods on the market, competing for the attention and exchange resources of buyers. Competition results from scarcity, as it is not possible to satisfy all conceivable human wants, and occurs as people try to meet the criteria being used to determine allocation.

In the works of Adam Smith, the idea of capitalism is made possible through competition which creates growth. Although capitalism has not entered mainstream economics at the time of Smith, it is vital to the construction of his ideal society. One of the foundational blocks of capitalism is competition. Smith believed that a prosperous society is one where "everyone should be free to enter and leave the market and change trades as often as he pleases." He believed that the freedom to act in one's self-interest is essential for the success of a capitalist society. The fear arises that if all participants focus on their own goals, society's well-being will be water under the bridge. Smith maintains that despite the concerns of intellectuals, "global trends will hardly be altered if they refrain from pursuing their personal ends." He insisted that the actions of a few participants cannot alter the course of society. Instead, Smith maintained that they should focus on personal progress instead and that this will result in overall growth to the whole. Competition between participants, "who are all endeavoring to jostle one another out of employment, obliges every man to endeavor to execute his work" through competition towards growth.

Economic growth

Economic growth is a characteristic tendency of capitalist economies.

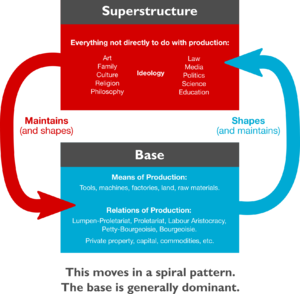

As a mode of production

The capitalist mode of production refers to the systems of organising production and distribution within capitalist societies. Private money-making in various forms (renting, banking, merchant trade, production for profit and so on) preceded the development of the capitalist mode of production as such. The capitalist mode of production proper based on wage-labor and private ownership of the means of production and on industrial technology began to grow rapidly in Western Europe from the Industrial Revolution, later extending to most of the world.

The term capitalist mode of production is defined by private ownership of the means of production, extraction of surplus value by the owning class for the purpose of capital accumulation, wage-based labor and, at least as far as commodities are concerned, being market-based.

Capitalism in the form of money-making activity has existed in the shape of merchants and money-lenders who acted as intermediaries between consumers and producers engaging in simple commodity production (hence the reference to "merchant capitalism") since the beginnings of civilisation. What is specific about the "capitalist mode of production" is that most of the inputs and outputs of production are supplied through the market (i.e. they are commodities) and essentially all production is in this mode. By contrast, in flourishing feudalism most or all of the factors of production, including labor, are owned by the feudal ruling class outright and the products may also be consumed without a market of any kind, it is production for use within the feudal social unit and for limited trade. This has the important consequence that, under capitalism, the whole organisation of the production process is reshaped and re-organised to conform with economic rationality as bounded by capitalism, which is expressed in price relationships between inputs and outputs (wages, non-labor factor costs, sales and profits) rather than the larger rational context faced by society overall—that is, the whole process is organised and re-shaped in order to conform to "commercial logic". Essentially, capital accumulation comes to define economic rationality in capitalist production.

A society, region or nation is capitalist if the predominant source of incomes and products being distributed is capitalist activity, but even so this does not yet mean necessarily that the capitalist mode of production is dominant in that society.

Role of government

Government agencies regulate the standards of service in many industries, such as airlines and broadcasting, as well as financing a wide range of programs. In addition, the government regulates the flow of capital and uses financial tools such as the interest rate to control such factors as inflation and unemployment.

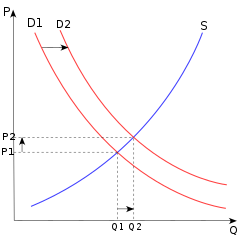

Supply and demand

In capitalist economic structures, supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a market. It postulates that in a perfectly competitive market, the unit price for a particular good will vary until it settles at a point where the quantity demanded by consumers (at the current price) will equal the quantity supplied by producers (at the current price), resulting in an economic equilibrium for price and quantity.

The "basic laws" of supply and demand, as described by David Besanko and Ronald Braeutigam, are the following four:

- If demand increases (demand curve shifts to the right) and supply remains unchanged, then a shortage occurs, leading to a higher equilibrium price.

- If demand decreases (demand curve shifts to the left) and supply remains unchanged, then a surplus occurs, leading to a lower equilibrium price.

- If demand remains unchanged and supply increases (supply curve shifts to the right), then a surplus occurs, leading to a lower equilibrium price.

- If demand remains unchanged and supply decreases (supply curve shifts to the left), then a shortage occurs, leading to a higher equilibrium price.

Supply schedule

A supply schedule is a table that shows the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity supplied.

Demand schedule

A demand schedule, depicted graphically as the demand curve, represents the amount of some goods that buyers are willing and able to purchase at various prices, assuming all determinants of demand other than the price of the good in question, such as income, tastes and preferences, the price of substitute goods and the price of complementary goods, remain the same. According to the law of demand, the demand curve is almost always represented as downward-sloping, meaning that as price decreases, consumers will buy more of the good.

Just like the supply curves reflect marginal cost curves, demand curves are determined by marginal utility curves.

Equilibrium

In the context of supply and demand, economic equilibrium refers to a state where economic forces such as supply and demand are balanced and in the absence of external influences the (equilibrium) values of economic variables will not change. For example, in the standard text-book model of perfect competition equilibrium occurs at the point at which quantity demanded and quantity supplied are equal. Market equilibrium, in this case, refers to a condition where a market price is established through competition such that the amount of goods or services sought by buyers is equal to the amount of goods or services produced by sellers. This price is often called the competitive price or market clearing price, and will tend not to change unless demand or supply changes. The quantity is called "competitive quantity" or market clearing quantity.

Partial equilibrium

Partial equilibrium, as the name suggests, takes into consideration only a part of the market to attain equilibrium. Jain proposes (attributed to George Stigler): "A partial equilibrium is one which is based on only a restricted range of data, a standard example is price of a single product, the prices of all other products being held fixed during the analysis".

History

According to Hamid S. Hosseini, the "power of supply and demand" was discussed to some extent by several early Muslim scholars, such as fourteenth-century Mamluk scholar Ibn Taymiyyah, who wrote: "If desire for goods increases while its availability decreases, its price rises. On the other hand, if availability of the good increases and the desire for it decreases, the price comes down".

John Locke's 1691 work Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money includes an early and clear description of supply and demand and their relationship. In this description, demand is rent: "The price of any commodity rises or falls by the proportion of the number of buyer and sellers" and "that which regulates the price... [of goods] is nothing else but their quantity in proportion to their rent".

David Ricardo titled one chapter of his 1817 work Principles of Political Economy and Taxation "On the Influence of Demand and Supply on Price". In Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Ricardo more rigorously laid down the idea of the assumptions that were used to build his ideas of supply and demand.

In his 1870 essay "On the Graphical Representation of Supply and Demand", Fleeming Jenkin in the course of "introduc[ing] the diagrammatic method into the English economic literature" published the first drawing of supply and demand curves therein, including comparative statics from a shift of supply or demand and application to the labor market. The model was further developed and popularized by Alfred Marshall in the 1890 textbook Principles of Economics.

Types

There are many variants of capitalism in existence that differ according to country and region. They vary in their institutional makeup and by their economic policies. The common features among all the different forms of capitalism is that they are predominantly based on the private ownership of the means of production and the production of goods and services for profit; the market-based allocation of resources; and the accumulation of capital.

They include advanced capitalism, corporate capitalism, finance capitalism, free-market capitalism, mercantilism, social capitalism, state capitalism and welfare capitalism. Other variants of capitalism include anarcho-capitalism, community capitalism, humanistic capitalism, neo-capitalism, state monopoly capitalism, and technocapitalism.

Advanced

Advanced capitalism is the situation that pertains to a society in which the capitalist model has been integrated and developed deeply and extensively for a prolonged period. Various writers identify Antonio Gramsci as an influential early theorist of advanced capitalism, even if he did not use the term himself. In his writings, Gramsci sought to explain how capitalism had adapted to avoid the revolutionary overthrow that had seemed inevitable in the 19th century. At the heart of his explanation was the decline of raw coercion as a tool of class power, replaced by use of civil society institutions to manipulate public ideology in the capitalists' favour.

Jürgen Habermas has been a major contributor to the analysis of advanced-capitalistic societies. Habermas observed four general features that characterise advanced capitalism:

- Concentration of industrial activity in a few large firms.

- Constant reliance on the state to stabilise the economic system.

- A formally democratic government that legitimises the activities of the state and dissipates opposition to the system.

- The use of nominal wage increases to pacify the most restless segments of the work force.

Corporate

Corporate capitalism is a free or mixed-market capitalist economy characterized by the dominance of hierarchical, bureaucratic corporations.

Finance

Finance capitalism is the subordination of processes of production to the accumulation of money profits in a financial system. In their critique of capitalism, Marxism and Leninism both emphasise the role of finance capital as the determining and ruling-class interest in capitalist society, particularly in the latter stages.

Rudolf Hilferding is credited with first bringing the term finance capitalism into prominence through Finance Capital, his 1910 study of the links between German trusts, banks and monopolies—a study subsumed by Vladimir Lenin into Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), his analysis of the imperialist relations of the great world powers. Lenin concluded that the banks at that time operated as "the chief nerve centres of the whole capitalist system of national economy". For the Comintern (founded in 1919), the phrase "dictatorship of finance capitalism" became a regular one.

Fernand Braudel would later point to two earlier periods when finance capitalism had emerged in human history—with the Genoese in the 16th century and with the Dutch in the 17th and 18th centuries—although at those points it developed from commercial capitalism. Giovanni Arrighi extended Braudel's analysis to suggest that a predominance of finance capitalism is a recurring, long-term phenomenon, whenever a previous phase of commercial/industrial capitalist expansion reaches a plateau.

Free-market

A capitalist free-market economy is an economic system where prices for goods and services are set entirely by the forces of supply and demand and are expected, by its adherents, to reach their point of equilibrium without intervention by government policy. It typically entails support for highly competitive markets and private ownership of the means of production. Laissez-faire capitalism is a more extensive form of this free-market economy, but one in which the role of the state is limited to protecting property rights. In anarcho-capitalist theory, property rights are protected by private firms and market-generated law. According to anarcho-capitalists, this entails property rights without statutory law through market-generated tort, contract and property law, and self-sustaining private industry.

Fernand Braudel argued that free market exchange and capitalism are to some degree opposed; free market exchange involves transparent public transactions and a large number of equal competitors, while capitalism involves a small number of participants using their capital to control the market via private transactions, control of information, and limitation of competition.

Mercantile

Mercantilism is a nationalist form of early capitalism that came into existence approximately in the late 16th century. It is characterized by the intertwining of national business interests with state-interest and imperialism. Consequently, the state apparatus is used to advance national business interests abroad. An example of this is colonists living in America who were only allowed to trade with and purchase goods from their respective mother countries (e.g. Britain, France and Portugal). Mercantilism was driven by the belief that the wealth of a nation is increased through a positive balance of trade with other nations—it corresponds to the phase of capitalist development sometimes called the primitive accumulation of capital.

Social

A social market economy is a free-market or mixed-market capitalist system, sometimes classified as a coordinated market economy, where government intervention in price formation is kept to a minimum, but the state provides significant services in areas such as social security, health care, unemployment benefits and the recognition of labor rights through national collective bargaining arrangements.

This model is prominent in Western and Northern European countries as well as Japan, albeit in slightly different configurations. The vast majority of enterprises are privately owned in this economic model.

Rhine capitalism is the contemporary model of capitalism and adaptation of the social market model that exists in continental Western Europe today.

State

State capitalism is a capitalist market economy dominated by state-owned enterprises, where the state enterprises are organized as commercial, profit-seeking businesses. The designation has been used broadly throughout the 20th century to designate a number of different economic forms, ranging from state-ownership in market economies to the command economies of the former Eastern Bloc. According to Aldo Musacchio, a professor at Harvard Business School, state capitalism is a system in which governments, whether democratic or autocratic, exercise a widespread influence on the economy either through direct ownership or various subsidies. Musacchio notes a number of differences between today's state capitalism and its predecessors. In his opinion, gone are the days when governments appointed bureaucrats to run companies: the world's largest state-owned enterprises are now traded on the public markets and kept in good health by large institutional investors. Contemporary state capitalism is associated with the East Asian model of capitalism, dirigisme and the economy of Norway. Alternatively, Merriam-Webster defines state capitalism as "an economic system in which private capitalism is modified by a varying degree of government ownership and control".

In Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, Friedrich Engels argued that state-owned enterprises would characterize the final stage of capitalism, consisting of ownership and management of large-scale production and communication by the bourgeois state. In his writings, Vladimir Lenin characterized the economy of Soviet Russia as state capitalist, believing state capitalism to be an early step toward the development of socialism.

Some economists and left-wing academics including Richard D. Wolff and Noam Chomsky, as well as many Marxist philosophers and revolutionaries such as Raya Dunayevskaya and C.L.R. James, argue that the economies of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc represented a form of state capitalism because their internal organization within enterprises and the system of wage labor remained intact.

The term is not used by Austrian School economists to describe state ownership of the means of production. The economist Ludwig von Mises argued that the designation of state capitalism was a new label for the old labels of state socialism and planned economy and differed only in non-essentials from these earlier designations.

The debate between proponents of private versus state capitalism is centered around questions of managerial efficacy, productive efficiency and fair distribution of wealth.

Welfare

Welfare capitalism is capitalism that includes social welfare policies. Today, welfare capitalism is most often associated with the models of capitalism found in Central Mainland and Northern Europe such as the Nordic model, social market economy and Rhine capitalism. In some cases, welfare capitalism exists within a mixed economy, but welfare states can and do exist independently of policies common to mixed economies such as state interventionism and extensive regulation.

A mixed economy is a largely market-based capitalist economy consisting of both private and public ownership of the means of production and economic interventionism through macroeconomic policies intended to correct market failures, reduce unemployment and keep inflation low. The degree of intervention in markets varies among different countries. Some mixed economies such as France under dirigisme also featured a degree of indirect economic planning over a largely capitalist-based economy.

Most modern capitalist economies are defined as mixed economies to some degree.

Eco-capitalism

Eco-capitalism, also known as "environmental capitalism" or (sometimes) "green capitalism", is the view that capital exists in nature as "natural capital" (ecosystems that have ecological yield) on which all wealth depends. Therefore, governments should use market-based policy-instruments (such as a carbon tax) to resolve environmental problems.

The term "Blue Greens" is often applied to those who espouse eco-capitalism. Eco-capitalism can be thought of as the right-wing equivalent to Red Greens.

Sustainable capitalism

Sustainable capitalism is a conceptual form of capitalism based upon sustainable practices that seek to preserve humanity and the planet, while reducing externalities and bearing a resemblance of capitalist economic policy. A capitalistic economy must expand to survive and find new markets to support this expansion. Capitalist systems are often destructive to the environment as well as certain individuals without access to proper representation. However, sustainability provides quite the opposite; it implies not only a continuation, but a replenishing of resources. Sustainability is often thought of to be related to environmentalism, and sustainable capitalism applies sustainable principles to economic governance and social aspects of capitalism as well.

The importance of sustainable capitalism has been more recently recognized, but the concept is not new. Changes to the current economic model would have heavy social environmental and economic implications and require the efforts of individuals, as well as compliance of local, state and federal governments. Controversy surrounds the concept as it requires an increase in sustainable practices and a marked decrease in current consumptive behaviors.

This is a concept of capitalism described in Al Gore and David Blood’s manifesto for the Generation Investment Management to describe a long-term political, economic and social structure which would mitigate current threats to the planet and society. According to their manifesto, sustainable capitalism would integrate the environmental, social and governance (ESG) aspects into risk assessment in attempt to limit externalities. Most of the ideas they list are related to economic changes, and social aspects, but strikingly few are explicitly related to any environmental policy change.

Capital accumulation

The accumulation of capital is the process of "making money", or growing an initial sum of money through investment in production. Capitalism is based on the accumulation of capital, whereby financial capital is invested in order to make a profit and then reinvested into further production in a continuous process of accumulation. In Marxian economic theory, this dynamic is called the law of value. Capital accumulation forms the basis of capitalism, where economic activity is structured around the accumulation of capital, defined as investment in order to realize a financial profit. In this context, "capital" is defined as money or a financial asset invested for the purpose of making more money (whether in the form of profit, rent, interest, royalties, capital gain or some other kind of return).

In mainstream economics, accounting and Marxian economics, capital accumulation is often equated with investment of profit income or savings, especially in real capital goods. The concentration and centralisation of capital are two of the results of such accumulation. In modern macroeconomics and econometrics, the phrase "capital formation" is often used in preference to "accumulation", though the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) refers nowadays to "accumulation". The term "accumulation" is occasionally used in national accounts.

Wage labor

Wage labor refers to the sale of labor under a formal or informal employment contract to an employer. These transactions usually occur in a labor market where wages are market determined. Individuals who possess and supply financial capital to productive ventures often become owners, either jointly (as shareholders) or individually. In Marxist economics, these owners of the means of production and suppliers of capital are generally called capitalists. The description of the role of the capitalist has shifted, first referring to a useless intermediary between producers, then to an employer of producers, and finally to the owners of the means of production. Labor includes all physical and mental human resources, including entrepreneurial capacity and management skills, which are required to produce products and services. Production is the act of making goods or services by applying labor power.

Criticism

Criticism of capitalism comes from various political and philosophical approaches, including anarchist, socialist, religious and nationalist viewpoints. Of those who oppose it or want to modify it, some believe that capitalism should be removed through revolution while others believe that it should be changed slowly through political reforms.

Prominent critiques of capitalism allege that it is inherently exploitative, alienating, unstable, unsustainable, and economically inefficient—and that it creates massive economic inequality, commodifies people, degrades the environment, is anti-democratic, and leads to an erosion of human rights because of its incentivization of imperialist expansion and war.