The 2000s United States housing bubble was a real-estate bubble affecting over half of the U.S. states. It was the impetus for the subprime mortgage crisis. Housing prices peaked in early 2006, started to decline in 2006 and 2007, and reached new lows in 2011. On December 30, 2008, the Case–Shiller home price index reported its largest price drop in its history. The credit crisis resulting from the bursting of the housing bubble is an important cause of the Great Recession in the United States.

Increased foreclosure rates in 2006–2007 among U.S. homeowners led to a crisis in August 2008 for the subprime, Alt-A, collateralized debt obligation (CDO), mortgage, credit, hedge fund, and foreign bank markets. In October 2007, Henry Paulson, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, called the bursting housing bubble "the most significant risk to our economy".

Any collapse of the U.S. housing bubble has a direct impact not only on home valuations, but mortgage markets, home builders, real estate, home supply retail outlets, Wall Street hedge funds held by large institutional investors, and foreign banks, increasing the risk of a nationwide recession. Concerns about the impact of the collapsing housing and credit markets on the larger U.S. economy caused President George W. Bush and the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke to announce a limited bailout of the U.S. housing market for homeowners who were unable to pay their mortgage debts.

In 2008 alone, the United States government allocated over $900 billion to special loans and rescues related to the U.S. housing bubble. This was shared between the public sector and the private sector. Because of the large market share of Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) (both of which are government-sponsored enterprises) as well as the Federal Housing Administration, they received a substantial share of government support, even though their mortgages were more conservatively underwritten and actually performed better than those of the private sector.

Background

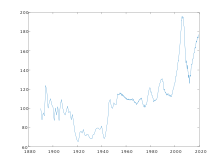

Land prices contributed much more to the price increases than did structures. This can be seen in the building cost index in Fig. 1. An estimate of land value for a house can be derived by subtracting the replacement value of the structure, adjusted for depreciation, from the home price. Using this methodology, Davis and Palumbo calculated land values for 46 U.S. metro areas, which can be found at the website for the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy.

Housing bubbles may occur in local or global real estate markets. In their late stages, they are typically characterized by rapid increases in the valuations of real property until unsustainable levels are reached relative to incomes, price-to-rent ratios, and other economic indicators of affordability. This may be followed by decreases in home prices that result in many owners finding themselves in a position of negative equity—a mortgage debt higher than the value of the property. The underlying causes of the housing bubble are complex. Factors include tax policy (exemption of housing from capital gains), historically low interest rates, lax lending standards, failure of regulators to intervene, and speculative fever. This bubble may be related to the stock market or dot-com bubble of the 1990s. This bubble roughly coincides with the real-estate bubbles of the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Spain, Poland, Hungary and South Korea.

While bubbles may be identifiable in progress, bubbles can be definitively measured only in hindsight after a market correction, which began in 2005–2006 for the U.S. housing market. Former U.S. Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan said "We had a bubble in housing", and also said in the wake of the subprime mortgage and credit crisis in 2007, "I really didn't get it until very late in 2005 and 2006." In 2001, Alan Greenspan dropped interest rates to a low 1% in order to jump the economy after the ".com" bubble. It was then bankers and other Wall Street firms started borrowing money due to its inexpensiveness.

The mortgage and credit crisis was caused by the inability of a large number of home owners to pay their mortgages as their low introductory-rate mortgages reverted to regular interest rates. Freddie Mac CEO Richard Syron concluded, "We had a bubble", and concurred with Yale economist Robert Shiller's warning that home prices appear overvalued and that the correction could last years, with trillions of dollars of home value being lost. Greenspan warned of "large double digit declines" in home values "larger than most people expect".

Problems for home owners with good credit surfaced in mid-2007, causing the United States' largest mortgage lender, Countrywide Financial, to warn that a recovery in the housing sector was not expected to occur at least until 2009 because home prices were falling "almost like never before, with the exception of the Great Depression". The impact of booming home valuations on the U.S. economy since the 2001–2002 recession was an important factor in the recovery, because a large component of consumer spending was fueled by the related refinancing boom, which allowed people to both reduce their monthly mortgage payments with lower interest rates and withdraw equity from their homes as their value increased.

Timeline

Identification

Although an economic bubble is difficult to identify except in hindsight, numerous economic and cultural factors led several economists (especially in late 2004 and early 2005) to argue that a housing bubble existed in the U.S. Dean Baker identified the bubble in August 2002, thereafter repeatedly warning of its nature and depth, and the political reasons it was being ignored. Prior to that, Robert Prechter wrote about it extensively as did Professor Shiller in his original publication of Irrational Exuberance in the year 2000.

The burst of the housing bubble was predicted by a handful of political and economic analysts, such as Jeffery Robert Hunn in a March 3, 2003, editorial. Hunn wrote:

[W]e can profit from the collapse of the credit bubble and the subsequent stock market divestment [(decline)]. However, real estate has not yet joined in a decline of prices fed by selling (and foreclosing). Unless you have a very specific reason to believe that real estate will outperform all other investments for several years, you may deem this prime time to liquidate investment property (for use in more lucrative markets).

Many contested any suggestion that there could be a housing bubble, particularly at its peak from 2004 to 2006, with some rejecting the "house bubble" label in 2008. Claims that there was no warning of the crisis were further repudiated in an August 2008 article in The New York Times, which reported that in mid-2004 Richard F. Syron, the CEO of Freddie Mac, received a memo from David Andrukonis, the company's former chief risk officer, warning him that Freddie Mac was financing risk-laden loans that threatened Freddie Mac's financial stability. In his memo, Mr. Andrukonis wrote that these loans "would likely pose an enormous financial and reputational risk to the company and the country". The article revealed that more than two-dozen high-ranking executives said that Mr. Syron had simply decided to ignore the warnings.

Other cautions came as early as 2001, when the late Federal Reserve governor Edward Gramlich warned of the risks posed by subprime mortgages. In September 2003, at a hearing of the House Financial Services Committee, Congressman Ron Paul identified the housing bubble and foretold the difficulties it would cause: "Like all artificially-created bubbles, the boom in housing prices cannot last forever. When housing prices fall, homeowners will experience difficulty as their equity is wiped out. Furthermore, the holders of the mortgage debt will also have a loss." Reuters reported in October 2007 that a Merrill Lynch analyst too had warned in 2006 that companies could suffer from their subprime investments.

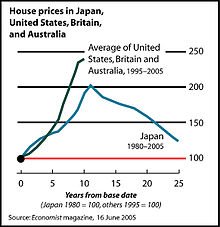

The Economist magazine stated, "The worldwide rise in house prices is the biggest bubble in history", so any explanation needs to consider its global causes as well as those specific to the United States. The then Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan said in mid-2005 that "at a minimum, there's a little 'froth' (in the U.S. housing market) ... it's hard not to see that there are a lot of local bubbles"; Greenspan admitted in 2007 that froth "was a euphemism for a bubble". In early 2006, President Bush said of the U.S. housing boom: "If houses get too expensive, people will stop buying them ... Economies should cycle".

Throughout the bubble period there was little if any mention of the fact that housing in many areas was (and still is) selling for well above replacement cost.

On the basis of 2006 market data that were indicating a marked decline, including lower sales, rising inventories, falling median prices and increased foreclosure rates, some economists have concluded that the correction in the U.S. housing market began in 2006. A May 2006 Fortune magazine report on the US housing bubble states: "The great housing bubble has finally started to deflate ... In many once-sizzling markets around the country, accounts of dropping list prices have replaced tales of waiting lists for unbuilt condos and bidding wars over humdrum three-bedroom colonials."

The chief economist of Freddie Mac and the director of Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) denied the existence of a national housing bubble and expressed doubt that any significant decline in home prices was possible, citing consistently rising prices since the Great Depression, an anticipated increased demand from the Baby Boom generation, and healthy levels of employment. However, some have suggested that the funding received by JCHS from the real estate industry may have affected their judgment. David Lereah, former chief economist of the National Association of Realtors (NAR), distributed "Anti-Bubble Reports" in August 2005 to "respond to the irresponsible bubble accusations made by your local media and local academics".

Among other statements, the reports stated that people "should [not] be concerned that home prices are rising faster than family income", that "there is virtually no risk of a national housing price bubble based on the fundamental demand for housing and predictable economic factors", and that "a general slowing in the rate of price growth can be expected, but in many areas inventory shortages will persist and home prices are likely to continue to rise above historic norms". Following reports of rapid sales declines and price depreciation in August 2006 Lereah admitted that he expected "home prices to come down 5% nationally, more in some markets, less in others. And a few cities in Florida and California, where home prices soared to nose-bleed heights, could have 'hard landings'."

National home sales and prices both fell dramatically in March 2007 — the steepest plunge since the 1989 Savings and Loan crisis. According to NAR data, sales were down 13% to 482,000 from the peak of 554,000 in March 2006, and the national median price fell nearly 6% to $217,000 from a peak of $230,200 in July 2006.

John A. Kilpatrick from Greenfield Advisors was cited by Bloomberg News on June 14, 2007, on the linkage between increased foreclosures and localized housing price declines: "Living in an area with multiple foreclosures can result in a 10 percent to 20 percent decrease in property values". He went on to say, "In some cases that can wipe out the equity of homeowners or leave them owing more on their mortgage than the house is worth. The innocent houses that just happen to be sitting next to those properties are going to take a hit."

The US Senate Banking Committee held hearings on the housing bubble and related loan practices in 2006, titled "The Housing Bubble and its Implications for the Economy" and "Calculated Risk: Assessing Non-Traditional Mortgage Products". Following the collapse of the subprime mortgage industry in March 2007, Senator Chris Dodd, Chairman of the Banking Committee held hearings and asked executives from the top five subprime mortgage companies to testify and explain their lending practices. Dodd said that "predatory lending" had endangered home ownership for millions of people. In addition, Democratic senators such as Senator Charles Schumer of New York were already proposing a federal government bailout of subprime borrowers in order to save homeowners from losing their residences.

Causes

Extent

Home price appreciation has been non-uniform to such an extent that some economists, including former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, have argued that United States was not experiencing a nationwide housing bubble per se, but a number of local bubbles. However, in 2007 Greenspan admitted that there was in fact a bubble in the U.S. housing market, and that "all the froth bubbles add up to an aggregate bubble".

Despite greatly relaxed lending standards and low interest rates, many regions of the country saw very little price appreciation during the "bubble period". Out of 20 largest metropolitan areas tracked by the S&P/Case-Shiller house price index, six (Dallas, Cleveland, Detroit, Denver, Atlanta, and Charlotte) saw less than 10% price growth in inflation-adjusted terms in 2001–2006. During the same period, seven metropolitan areas (Tampa, Miami, San Diego, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Washington, D.C.) appreciated by more than 80%.

However, housing bubbles did not manifest themselves in each of these areas at the same time. San Diego and Los Angeles had maintained consistently high appreciation rates since late 1990s, whereas the Las Vegas and Phoenix bubbles did not develop until 2003 and 2004 respectively. It was in the East Coast, the more populated part of the country where the economic real estate turmoil was the worst.

Somewhat paradoxically, as the housing bubble deflates some metropolitan areas (such as Denver and Atlanta) have been experiencing high foreclosure rates, even though they did not see much house appreciation in the first place and therefore did not appear to be contributing to the national bubble. This was also true of some cities in the Rust Belt such as Detroit and Cleveland, where weak local economies had produced little house price appreciation early in the decade but still saw declining values and increased foreclosures in 2007. As of January 2009 California, Michigan, Ohio and Florida were the states with the highest foreclosure rates.

By July 2008, year-to-date prices had declined in 24 of 25 U.S. metropolitan areas, with California and the southwest experiencing the greatest price falls. According to the reports, only Milwaukee had seen an increase in house prices after July 2007.

Side effects

Prior to the real estate market correction of 2006–2007, the unprecedented increase in house prices starting in 1997 produced numerous wide-ranging effects in the economy of the United States.

- One of the most direct effects was on the construction of new houses. In 2005, 1,283,000 new single-family houses were sold, compared with an average of 609,000 per year during 1990–1995. The largest home builders, such as D. R. Horton, PulteGroup, and Lennar, improved operations significantly. D. R. Horton's stock went from $3 in early 1997 to all-time high of $42.82 on July 20, 2005. Pulte Corp's revenues grew from $2.33 billion in 1996 to $14.69 billion in 2005.

- Mortgage equity withdrawals – primarily home equity loans and cash out refinancings – grew considerably since the early 1990s. According to US Federal Reserve estimates, in 2005 homeowners extracted $750 billion of equity from their homes (up from $106 billion in 1996), spending two thirds of it on personal consumption, home improvements, and credit card debt.

- It is widely believed that the increased degree of economic activity produced by the expanding housing bubble in 2001–2003 was partly responsible for averting a full-scale recession in the U.S. economy following the dot-com bust and offshoring to China. Analysts believed that with the downturn in the two sectors, the economy from the early 2000s to 2007 evaded what would have been stagnant growth with a booming housing market creating jobs, economic demand along with a consumer boom that came from home value withdraws until the housing market began a correction.

- Rapidly growing house prices and increasing price gradients forced many residents to flee the expensive centers of many metropolitan areas, resulting in the explosive growth of exurbs in some regions. The population of Riverside County, California almost doubled from 1,170,413 in 1990 to 2,026,803 in 2006, due to its relative proximity to San Diego and Los Angeles. On the East Coast, Loudoun County, Virginia, near Washington, D.C., saw its population triple between 1990 and 2006.

- Extreme regional differences in land prices. The differences in housing prices are mainly due to differences in land values, which reached 85% of the total value of houses in the highest priced markets at the peak. The Wisconsin Business School publishes an on line database with building cost and land values for 46 U.S. metro areas. One of the fastest-growing regions in the United States for the last several decades was the Atlanta, Georgia metro area, where land values are a small fraction of those in the high-priced markets. High land values contribute to high living costs in general and are part of the reason for the decline of the old industrial centers while new automobile plants, for example, were built throughout the South, which grew in population faster than the other regions.

- People who either experienced foreclosures or live near foreclosures have a higher probability of falling ill or at the very least dealing with increased anxiety. Overall, it is reported that homeowners who are unable to afford living in their desired locations experience higher instances of poor health. Besides health issues, the unstable housing market has also been shown to increase instances of violence. They subsequently begin to fear that their own homes may be taken from them. Increases in anxiety have at the very least been commonly noted. There is a fear that foreclosures bring about these reactions in people who anticipate the same thing happening to them. An uptick on violent occurrences has also been shown to follow neighborhoods where such uncertainty exists.

These trends were reversed during the real estate market correction of 2006–2007. As of August 2007, D.R. Horton's and Pulte Corp's shares had fallen to 1/3 of their respective peak levels as new residential home sales fell. Some of the cities and regions that had experienced the fastest growth during 2000–2005 began to experience high foreclosure rates. It was suggested that the weakness of the housing industry and the loss of the consumption that had been driven by the withdrawal of mortgage equity could lead to a recession, but as of mid-2007 the existence of this recession had not yet been ascertained. In March 2008, Thomson Financial reported that the "Chicago Federal Reserve Bank's National Activity Index for February sent a signal that a recession [had] probably begun".

The share prices of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac plummeted in 2008 as investors worried that they lacked sufficient capital to cover the losses on their $5 trillion portfolio of loans and loan guarantees. On June 16, 2010, it was announced that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would be delisted from the New York Stock Exchange; shares now trade on the over-the-counter market.

Housing market correction

Comparison of the percentage change in the Case-Shiller Home Price Index for the housing corrections in the periods beginning in 2005 (red) and the 1980s–1990s (blue), comparing monthly CSI

values with the peak values immediately prior to the first month of

decline all the way through the downturn and the full recovery of home

prices. | |

|

Basing their statements on historic U.S. housing valuation trends, in 2005 and 2006 many economists and business writers predicted market corrections ranging from a few percentage points to 50% or more from peak values in some markets, and although this cooling had not yet affected all areas of the U.S., some warned that it still could, and that the correction would be "nasty" and "severe". Chief economist Mark Zandi of the economic research firm Moody's Economy.com predicted a "crash" of double-digit depreciation in some U.S. cities by 2007–2009. In a paper he presented to a Federal Reserve Board economic symposium in August 2007, Yale University economist Robert Shiller warned, "The examples we have of past cycles indicate that major declines in real home prices—even 50 percent declines in some places—are entirely possible going forward from today or from the not-too-distant future."

To better understand how the mortgage crisis played out, a 2012 report from the University of Michigan analyzed data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), which surveyed roughly 9,000 representative households in 2009 and 2011. The data seems to indicate that, while conditions are still difficult, in some ways the crisis is easing: Over the period studied, the percentage of families behind on mortgage payments fell from 2.2 to 1.9; homeowners who thought it was "very likely or somewhat likely" that they would fall behind on payments fell from 6% to 4.6% of families. On the other hand, family's financial liquidity has decreased: "As of 2009, 18.5% of families had no liquid assets, and by 2011 this had grown to 23.4% of families."

By mid-2016, the national housing price index was "about 1 percent shy of that 2006 bubble peak" in nominal terms but 20% below in inflation adjusted terms.

Subprime mortgage industry collapse

In March 2007, the United States' subprime mortgage industry collapsed due to higher-than-expected home foreclosure rates (no verifying source), with more than 25 subprime lenders declaring bankruptcy, announcing significant losses, or putting themselves up for sale. The stock of the country's largest subprime lender, New Century Financial, plunged 84% amid Justice Department investigations, before ultimately filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on April 2, 2007, with liabilities exceeding $100 million.

The manager of the world's largest bond fund, PIMCO, warned in June 2007 that the subprime mortgage crisis was not an isolated event and would eventually take a toll on the economy and ultimately have an impact in the form of impaired home prices. Bill Gross, a "most reputable financial guru", sarcastically and ominously criticized the credit ratings of the mortgage-based CDOs now facing collapse:

AAA? You were wooed, Mr. Moody's and Mr. Poor's, by the makeup, those six-inch hooker heels, and a "tramp stamp." Many of these good-looking girls are not high-class assets worth 100 cents on the dollar ... [T]he point is that there are hundreds of billions of dollars of this toxic waste ... This problem [ultimately] resides in America's heartland, with millions and millions of overpriced homes.

Business Week has featured predictions by financial analysts that the subprime mortgage market meltdown would result in earnings reductions for large Wall Street investment banks trading in mortgage-backed securities, especially Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley. The solvency of two troubled hedge funds managed by Bear Stearns was imperiled in June 2007 after Merrill Lynch sold off assets seized from the funds and three other banks closed out their positions with them. The Bear Stearns funds once had over $20 billion of assets, but lost billions of dollars on securities backed by subprime mortgages.

H&R Block reported that it had made a quarterly loss of $677 million on discontinued operations, which included the subprime lender Option One, as well as writedowns, loss provisions for mortgage loans and the lower prices achievable for mortgages in the secondary market. The unit's net asset value had fallen 21% to $1.1 billion as of April 30, 2007. The head of the mortgage industry consulting firm Wakefield Co. warned, "This is going to be a meltdown of unparalleled proportions. Billions will be lost." Bear Stearns pledged up to U.S. $3.2 billion in loans on June 22, 2007, to bail out one of its hedge funds that was collapsing because of bad bets on subprime mortgages.

Peter Schiff, president of Euro Pacific Capital, argued that if the bonds in the Bear Stearns funds were auctioned on the open market, much weaker values would be plainly revealed. Schiff added, "This would force other hedge funds to similarly mark down the value of their holdings. Is it any wonder that Wall street is pulling out the stops to avoid such a catastrophe? ... Their true weakness will finally reveal the abyss into which the housing market is about to plummet." The New York Times report connects the hedge fund crisis with lax lending standards: "The crisis this week from the near collapse of two hedge funds managed by Bear Stearns stems directly from the slumping housing market and the fallout from loose lending practices that showered money on people with weak, or subprime, credit, leaving many of them struggling to stay in their homes."

On August 9, 2007, BNP Paribas announced that it could not fairly value the underlying assets in three funds because of its exposure to U.S. subprime mortgage lending markets. Faced with potentially massive (though unquantifiable) exposure, the European Central Bank (ECB) immediately stepped in to ease market worries by opening lines of €96.8 billion (U.S. $130 billion) of low-interest credit. One day after the financial panic about a credit crunch had swept through Europe, the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank conducted an "open market operation" to inject U.S. $38 billion in temporary reserves into the system to help overcome the ill effects of a spreading credit crunch, on top of a similar move the previous day. In order to further ease the credit crunch in the U.S. credit market, at 8:15 a.m. on August 17, 2007, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank Ben Bernanke decided to lower the discount window rate, which is the lending rate between banks and the Federal Reserve Bank, by 50 basis points to 5.75% from 6.25%. The Federal Reserve Bank stated that the recent turmoil in the U.S. financial markets had raised the risk of an economic downturn.

In the wake of the mortgage industry meltdown, Senator Chris Dodd, chairman of the Banking Committee, held hearings in March 2007 in which he asked executives from the top five subprime mortgage companies to testify and explain their lending practices. Dodd said that "predatory lending practices" were endangering home ownership for millions of people. In addition, Democratic senators such as Senator Charles Schumer of New York were already proposing a federal government bailout of subprime borrowers like the bailout made in the savings and loan crisis, in order to save homeowners from losing their residences. Opponents of such a proposal asserted that a government bailout of subprime borrowers was not in the best interests of the U.S. economy because it would simply set a bad precedent, create a moral hazard, and worsen the speculation problem in the housing market.

Lou Ranieri of Salomon Brothers, creator of the mortgage-backed securities market in the 1970s, warned of the future impact of mortgage defaults: "This is the leading edge of the storm ... If you think this is bad, imagine what it's going to be like in the middle of the crisis." In his opinion, more than $100 billion of home loans were likely to default when the problems seen in the subprime industry also emerge in the prime mortgage markets.

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan had praised the rise of the subprime mortgage industry and the tools which it uses to assess credit-worthiness in an April 2005 speech. Because of these remarks, as well as his encouragement of the use of adjustable-rate mortgages, Greenspan has been criticized for his role in the rise of the housing bubble and the subsequent problems in the mortgage industry that triggered the economic crisis of 2008. On October 15, 2008, Anthony Faiola, Ellen Nakashima and Jill Drew wrote a lengthy article in The Washington Post titled, "What Went Wrong". In their investigation, the authors claim that Greenspan vehemently opposed any regulation of financial instruments known as derivatives. They further claim that Greenspan actively sought to undermine the office of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, specifically under the leadership of Brooksley E. Born, when the Commission sought to initiate the regulation of derivatives. Ultimately, it was the collapse of a specific kind of derivative, the mortgage-backed security, that triggered the economic crisis of 2008. Concerning the subprime mortgage mess, Greenspan later admitted that "I really didn't get it until very late in 2005 and 2006."

On September 13, 2007, the British bank Northern Rock applied to the Bank of England for emergency funds because of liquidity problems related to the subprime crisis. This precipitated a bank run at Northern Rock branches across the UK by concerned customers who took out "an estimated £2bn withdrawn in just three days".