The natural environment or natural world encompasses all living and non-living things occurring naturally, meaning in this case not artificial. The term is most often applied to the Earth or some parts of Earth. This environment encompasses the interaction of all living species, climate, weather and natural resources that affect human survival and economic activity. The concept of the natural environment can be distinguished as components:

- Complete ecological units that function as natural systems without massive civilized human intervention, including all vegetation, microorganisms, soil, rocks, the atmosphere, and natural phenomena that occur within their boundaries and their nature.

- Universal natural resources and physical phenomena that lack clear-cut boundaries, such as air, water, and climate, as well as energy, radiation, electric charge, and magnetism, not originating from civilized human actions.

In contrast to the natural environment is the built environment. Built environments are where humans have fundamentally transformed landscapes such as urban settings and agricultural land conversion, the natural environment is greatly changed into a simplified human environment. Even acts which seem less extreme, such as building a mud hut or a photovoltaic system in the desert, the modified environment becomes an artificial one. Though many animals build things to provide a better environment for themselves, they are not human, hence beaver dams, and the works of mound-building termites, are thought of as natural.

People cannot find absolutely natural environments on Earth, and naturalness usually varies in a continuum, from 100% natural in one extreme to 0% natural in the other. The massive environmental changes of humanity in the Anthropocene have fundamentally effected all natural environments: including from climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution from plastic and other chemicals in the air and water. More precisely, we can consider the different aspects or components of an environment, and see that their degree of naturalness is not uniform. If, for instance, in an agricultural field, the mineralogic composition and the structure of its soil are similar to those of an undisturbed forest soil, but the structure is quite different.

Composition

Earth science generally recognizes four spheres, the lithosphere, the hydrosphere, the atmosphere, and the biosphere as correspondent to rocks, water, air, and life respectively. Some scientists include as part of the spheres of the Earth, the cryosphere (corresponding to ice) as a distinct portion of the hydrosphere, as well as the pedosphere (to soil) as an active and intermixed sphere. Earth science (also known as geoscience, the geographical sciences or the Earth Sciences), is an all-embracing term for the sciences related to the planet Earth. There are four major disciplines in earth sciences, namely geography, geology, geophysics and geodesy. These major disciplines use physics, chemistry, biology, chronology and mathematics to build a qualitative and quantitative understanding of the principal areas or spheres of Earth.

Geological activity

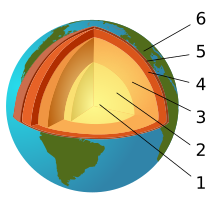

The Earth's crust, or lithosphere, is the outermost solid surface of the planet and is chemically and mechanically different from underlying mantle. It has been generated greatly by igneous processes in which magma cools and solidifies to form solid rock. Beneath the lithosphere lies the mantle which is heated by the decay of radioactive elements. The mantle though solid is in a state of rheic convection. This convection process causes the lithospheric plates to move, albeit slowly. The resulting process is known as plate tectonics. Volcanoes result primarily from the melting of subducted crust material or of rising mantle at mid-ocean ridges and mantle plumes.

Water on Earth

Most water is found in various kinds of natural body of water.

Oceans

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the surface of the Earth (an area of some 362 million square kilometers) is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas. More than half of this area is over 3,000 meters (9,800 ft) deep. Average oceanic salinity is around 35 parts per thousand (ppt) (3.5%), and nearly all seawater has a salinity in the range of 30 to 38 ppt. Though generally recognized as several separate oceans, these waters comprise one global, interconnected body of salt water often referred to as the World Ocean or global ocean. The deep seabeds are more than half the Earth's surface, and are among the least-modified natural environments. The major oceanic divisions are defined in part by the continents, various archipelagos, and other criteria: these divisions are (in descending order of size) the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean and the Arctic Ocean.

Rivers

A river is a natural watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing toward an ocean, a lake, a sea or another river. A few rivers simply flow into the ground and dry up completely without reaching another body of water.

The water in a river is usually in a channel, made up of a stream bed between banks. In larger rivers there is often also a wider floodplain shaped by waters over-topping the channel. Flood plains may be very wide in relation to the size of the river channel. Rivers are a part of the hydrological cycle. Water within a river is generally collected from precipitation through surface runoff, groundwater recharge, springs, and the release of water stored in glaciers and snowpacks.

Small rivers may also be called by several other names, including stream, creek and brook. Their current is confined within a bed and stream banks. Streams play an important corridor role in connecting fragmented habitats and thus in conserving biodiversity. The study of streams and waterways in general is known as surface hydrology.

Lakes

A lake (from Latin lacus) is a terrain feature, a body of water that is localized to the bottom of basin. A body of water is considered a lake when it is inland, is not part of an ocean, and is larger and deeper than a pond.

Natural lakes on Earth are generally found in mountainous areas, rift zones, and areas with ongoing or recent glaciation. Other lakes are found in endorheic basins or along the courses of mature rivers. In some parts of the world, there are many lakes because of chaotic drainage patterns left over from the last ice age. All lakes are temporary over geologic time scales, as they will slowly fill in with sediments or spill out of the basin containing them.

Ponds

A pond is a body of standing water, either natural or man-made, that is usually smaller than a lake. A wide variety of man-made bodies of water are classified as ponds, including water gardens designed for aesthetic ornamentation, fish ponds designed for commercial fish breeding, and solar ponds designed to store thermal energy. Ponds and lakes are distinguished from streams by their current speed. While currents in streams are easily observed, ponds and lakes possess thermally driven micro-currents and moderate wind driven currents. These features distinguish a pond from many other aquatic terrain features, such as stream pools and tide pools.

Human impact on water

Humans impact the water in different ways such as modifying rivers (through dams and stream channelization), urbanization, and deforestation. These impact lake levels, groundwater conditions, water pollution, thermal pollution, and marine pollution. Humans modify rivers by using direct channel manipulation. We build dams and reservoirs and manipulate the direction of the rivers and water path. Dams can usefully create reservoirs and hydroelectric power. However, reservoirs and dams may negatively impact the environment and wildlife. Dams stop fish migration and the movement of organisms downstream. Urbanization affects the environment because of deforestation and changing lake levels, groundwater conditions, etc. Deforestation and urbanization go hand in hand. Deforestation may cause flooding, declining stream flow, and changes in riverside vegetation. The changing vegetation occurs because when trees cannot get adequate water they start to deteriorate, leading to a decreased food supply for the wildlife in an area.

Atmosphere, climate and weather

The atmosphere of the Earth serves as a key factor in sustaining the planetary ecosystem. The thin layer of gases that envelops the Earth is held in place by the planet's gravity. Dry air consists of 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, 1% argon and other inert gases, and carbon dioxide. The remaining gases are often referred to as trace gases. The atmosphere includes greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone. Filtered air includes trace amounts of many other chemical compounds. Air also contains a variable amount of water vapor and suspensions of water droplets and ice crystals seen as clouds. Many natural substances may be present in tiny amounts in an unfiltered air sample, including dust, pollen and spores, sea spray, volcanic ash, and meteoroids. Various industrial pollutants also may be present, such as chlorine (elementary or in compounds), fluorine compounds, elemental mercury, and sulphur compounds such as sulphur dioxide (SO2).

The ozone layer of the Earth's atmosphere plays an important role in reducing the amount of ultraviolet (UV) radiation that reaches the surface. As DNA is readily damaged by UV light, this serves to protect life at the surface. The atmosphere also retains heat during the night, thereby reducing the daily temperature extremes.

Layers of the atmosphere

Principal layers

Earth's atmosphere can be divided into five main layers. These layers are mainly determined by whether temperature increases or decreases with altitude. From highest to lowest, these layers are:

- Exosphere: The outermost layer of Earth's atmosphere extends from the exobase upward, mainly composed of hydrogen and helium.

- Thermosphere: The top of the thermosphere is the bottom of the exosphere, called the exobase. Its height varies with solar activity and ranges from about 350–800 km (220–500 mi; 1,150,000–2,620,000 ft). The International Space Station orbits in this layer, between 320 and 380 km (200 and 240 mi).

- Mesosphere: The mesosphere extends from the stratopause to 80–85 km (50–53 mi; 262,000–279,000 ft). It is the layer where most meteors burn up upon entering the atmosphere.

- Stratosphere: The stratosphere extends from the tropopause to about 51 km (32 mi; 167,000 ft). The stratopause, which is the boundary between the stratosphere and mesosphere, typically is at 50 to 55 km (31 to 34 mi; 164,000 to 180,000 ft).

- Troposphere: The troposphere begins at the surface and extends to between 7 km (23,000 ft) at the poles and 17 km (56,000 ft) at the equator, with some variation due to weather. The troposphere is mostly heated by transfer of energy from the surface, so on average the lowest part of the troposphere is warmest and temperature decreases with altitude. The tropopause is the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere.

- Other layers

Within the five principal layers determined by temperature there are several layers determined by other properties.

- The ozone layer is contained within the stratosphere. It is mainly located in the lower portion of the stratosphere from about 15–35 km (9.3–21.7 mi; 49,000–115,000 ft), though the thickness varies seasonally and geographically. About 90% of the ozone in our atmosphere is contained in the stratosphere.

- The ionosphere, the part of the atmosphere that is ionized by solar radiation, stretches from 50 to 1,000 km (31 to 621 mi; 160,000 to 3,280,000 ft) and typically overlaps both the exosphere and the thermosphere. It forms the inner edge of the magnetosphere.

- The homosphere and heterosphere: The homosphere includes the troposphere, stratosphere, and mesosphere. The upper part of the heterosphere is composed almost completely of hydrogen, the lightest element.

- The planetary boundary layer is the part of the troposphere that is nearest the Earth's surface and is directly affected by it, mainly through turbulent diffusion.

Effects of global warming

The dangers of global warming are being increasingly studied by a wide global consortium of scientists. These scientists are increasingly concerned about the potential long-term effects of global warming on our natural environment and on the planet. Of particular concern is how climate change and global warming caused by anthropogenic, or human-made releases of greenhouse gases, most notably carbon dioxide, can act interactively, and have adverse effects upon the planet, its natural environment and humans' existence. It is clear the planet is warming, and warming rapidly. This is due to the greenhouse effect, which is caused by greenhouse gases, which trap heat inside the Earth's atmosphere because of their more complex molecular structure which allows them to vibrate and in turn trap heat and release it back towards the Earth. This warming is also responsible for the extinction of natural habitats, which in turn leads to a reduction in wildlife population. The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (the group of the leading climate scientists in the world) concluded that the earth will warm anywhere from 2.7 to almost 11 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 to 6 degrees Celsius) between 1990 and 2100. Efforts have been increasingly focused on the mitigation of greenhouse gases that are causing climatic changes, on developing adaptative strategies to global warming, to assist humans, other animal, and plant species, ecosystems, regions and nations in adjusting to the effects of global warming. Some examples of recent collaboration to address climate change and global warming include:

- The United Nations Framework Convention Treaty and convention on Climate Change, to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.

- The Kyoto Protocol, which is the protocol to the international Framework Convention on Climate Change treaty, again with the objective of reducing greenhouse gases in an effort to prevent anthropogenic climate change.

- The Western Climate Initiative, to identify, evaluate, and implement collective and cooperative ways to reduce greenhouse gases in the region, focusing on a market-based cap-and-trade system.

A significantly profound challenge is to identify the natural environmental dynamics in contrast to environmental changes not within natural variances. A common solution is to adapt a static view neglecting natural variances to exist. Methodologically, this view could be defended when looking at processes which change slowly and short time series, while the problem arrives when fast processes turns essential in the object of the study.

Climate

Climate looks at the statistics of temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, wind, rainfall, atmospheric particle count and other meteorological elements in a given region over long periods of time. Weather, on the other hand, is the present condition of these same elements over periods up to two weeks.

Climates can be classified according to the average and typical ranges of different variables, most commonly temperature and precipitation. The most commonly used classification scheme is the one originally developed by Wladimir Köppen. The Thornthwaite system, in use since 1948, uses evapotranspiration as well as temperature and precipitation information to study animal species diversity and the potential impacts of climate changes.

Weather

Weather is a set of all the phenomena occurring in a given atmospheric area at a given time. Most weather phenomena occur in the troposphere, just below the stratosphere. Weather refers, generally, to day-to-day temperature and precipitation activity, whereas climate is the term for the average atmospheric conditions over longer periods of time. When used without qualification, "weather" is understood to be the weather of Earth.

Weather occurs due to density (temperature and moisture) differences between one place and another. These differences can occur due to the sun angle at any particular spot, which varies by latitude from the tropics. The strong temperature contrast between polar and tropical air gives rise to the jet stream. Weather systems in the mid-latitudes, such as extratropical cyclones, are caused by instabilities of the jet stream flow. Because the Earth's axis is tilted relative to its orbital plane, sunlight is incident at different angles at different times of the year. On the Earth's surface, temperatures usually range ±40 °C (100 °F to −40 °F) annually. Over thousands of years, changes in the Earth's orbit have affected the amount and distribution of solar energy received by the Earth and influence long-term climate

Surface temperature differences in turn cause pressure differences. Higher altitudes are cooler than lower altitudes due to differences in compressional heating. Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology to predict the state of the atmosphere for a future time and a given location. The atmosphere is a chaotic system, and small changes to one part of the system can grow to have large effects on the system as a whole. Human attempts to control the weather have occurred throughout human history, and there is evidence that civilized human activity such as agriculture and industry has inadvertently modified weather patterns.

Life

Evidence suggests that life on Earth has existed for about 3.7 billion years. All known life forms share fundamental molecular mechanisms, and based on these observations, theories on the origin of life attempt to find a mechanism explaining the formation of a primordial single cell organism from which all life originates. There are many different hypotheses regarding the path that might have been taken from simple organic molecules via pre-cellular life to protocells and metabolism.

Although there is no universal agreement on the definition of life, scientists generally accept that the biological manifestation of life is characterized by organization, metabolism, growth, adaptation, response to stimuli and reproduction. Life may also be said to be simply the characteristic state of organisms. In biology, the science of living organisms, "life" is the condition which distinguishes active organisms from inorganic matter, including the capacity for growth, functional activity and the continual change preceding death.

A diverse variety of living organisms (life forms) can be found in the biosphere on Earth, and properties common to these organisms—plants, animals, fungi, protists, archaea, and bacteria—are a carbon- and water-based cellular form with complex organization and heritable genetic information. Living organisms undergo metabolism, maintain homeostasis, possess a capacity to grow, respond to stimuli, reproduce and, through natural selection, adapt to their environment in successive generations. More complex living organisms can communicate through various means.

Ecosystems

An ecosystem (also called as environment) is a natural unit consisting of all plants, animals and micro-organisms (biotic factors) in an area functioning together with all of the non-living physical (abiotic) factors of the environment.

Central to the ecosystem concept is the idea that living organisms are continually engaged in a highly interrelated set of relationships with every other element constituting the environment in which they exist. Eugene Odum, one of the founders of the science of ecology, stated: "Any unit that includes all of the organisms (i.e.: the "community") in a given area interacting with the physical environment so that a flow of energy leads to clearly defined trophic structure, biotic diversity, and material cycles (i.e.: exchange of materials between living and nonliving parts) within the system is an ecosystem."

The human ecosystem concept is then grounded in the deconstruction of the human/nature dichotomy, and the emergent premise that all species are ecologically integrated with each other, as well as with the abiotic constituents of their biotope.

A greater number or variety of species or biological diversity of an ecosystem may contribute to greater resilience of an ecosystem, because there are more species present at a location to respond to change and thus "absorb" or reduce its effects. This reduces the effect before the ecosystem's structure is fundamentally changed to a different state. This is not universally the case and there is no proven relationship between the species diversity of an ecosystem and its ability to provide goods and services on a sustainable level.

The term ecosystem can also pertain to human-made environments, such as human ecosystems and human-influenced ecosystems, and can describe any situation where there is relationship between living organisms and their environment. Fewer areas on the surface of the earth today exist free from human contact, although some genuine wilderness areas continue to exist without any forms of human intervention.

Biogeochemical cycles

Global biogeochemical cycles are critical to life, most notably those of water, oxygen, carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus.

- The nitrogen cycle is the transformation of nitrogen and nitrogen-containing compounds in nature. It is a cycle which includes gaseous components.

- The water cycle, is the continuous movement of water on, above, and below the surface of the Earth. Water can change states among liquid, vapour, and ice at various places in the water cycle. Although the balance of water on Earth remains fairly constant over time, individual water molecules can come and go.

- The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of the Earth.

- The oxygen cycle is the movement of oxygen within and between its three main reservoirs: the atmosphere, the biosphere, and the lithosphere. The main driving factor of the oxygen cycle is photosynthesis, which is responsible for the modern Earth's atmospheric composition and life.

- The phosphorus cycle is the movement of phosphorus through the lithosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere. The atmosphere does not play a significant role in the movements of phosphorus, because phosphorus and phosphorus compounds are usually solids at the typical ranges of temperature and pressure found on Earth.

Wilderness

Wilderness is generally defined as a natural environment on Earth that has not been significantly modified by human activity. The WILD Foundation goes into more detail, defining wilderness as: "The most intact, undisturbed wild natural areas left on our planet – those last truly wild places that humans do not control and have not developed with roads, pipelines or other industrial infrastructure." Wilderness areas and protected parks are considered important for the survival of certain species, ecological studies, conservation, solitude, and recreation. Wilderness is deeply valued for cultural, spiritual, moral, and aesthetic reasons. Some nature writers believe wilderness areas are vital for the human spirit and creativity.

The word, "wilderness", derives from the notion of wildness; in other words that which is not controllable by humans. The word's etymology is from the Old English wildeornes, which in turn derives from wildeor meaning wild beast (wild + deor = beast, deer). From this point of view, it is the wildness of a place that makes it a wilderness. The mere presence or activity of people does not disqualify an area from being "wilderness." Many ecosystems that are, or have been, inhabited or influenced by activities of people may still be considered "wild." This way of looking at wilderness includes areas within which natural processes operate without very noticeable human interference.

Wildlife includes all non-domesticated plants, animals and other organisms. Domesticating wild plant and animal species for human benefit has occurred many times all over the planet, and has a major impact on the environment, both positive and negative. Wildlife can be found in all ecosystems. Deserts, rain forests, plains, and other areas—including the most developed urban sites—all have distinct forms of wildlife. While the term in popular culture usually refers to animals that are untouched by civilized human factors, most scientists agree that wildlife around the world is (now) impacted by human activities.

Challenges

It is the common understanding of natural environment that underlies environmentalism — a broad political, social, and philosophical movement that advocates various actions and policies in the interest of protecting what nature remains in the natural environment, or restoring or expanding the role of nature in this environment. While true wilderness is increasingly rare, wild nature (e.g., unmanaged forests, uncultivated grasslands, wildlife, wildflowers) can be found in many locations previously inhabited by humans.

Goals for the benefit of people and natural systems, commonly expressed by environmental scientists and environmentalists include:

- Elimination of pollution and toxicants in air, water, soil, buildings, manufactured goods, and food.

- Preservation of biodiversity and protection of endangered species.

- Conservation and sustainable use of resources such as water, land, air, energy, raw materials, and natural resources.

- Halting human-induced global warming, which represents pollution, a threat to biodiversity, and a threat to human populations.

- Shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy in electricity, heating and cooling, and transportation, which addresses pollution, global warming, and sustainability. This may include public transportation and distributed generation, which have benefits for traffic congestion and electric reliability.

- Shifting from meat-intensive diets to largely plant-based diets in order to help mitigate biodiversity loss and climate change.

- Establishment of nature reserves for recreational purposes and ecosystem preservation.

- Sustainable and less polluting waste management including waste reduction (or even zero waste), reuse, recycling, composting, waste-to-energy, and anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge.

- Reducing profligate consumption and clamping down on illegal fishing and logging.

- Slowing and stabilisation of human population growth.

Criticism

In some cultures the term environment is meaningless because there is no separation between people and what they view as the natural world, or their surroundings. Specifically in the United States and Arabian countries many native cultures do not recognize the "environment", or see themselves as environmentalists.