From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Habsburg

| House of Habsburg Haus Habsburg | |

|---|---|

| Imperial, Royal, and Ducal dynasty | |

Top: Habsburg "ancient", coat of arms of the Counts of Habsburg: Or, a lion rampant gules crowned azure ("Lion of Habsburg"); bottom: Habsburg "modern"/Austria, arms of the House of Habsburg, Archdukes of Austria: Gules, a fess argent ("Bindenschild"); originally the arms of the House of Babenburg, Dukes of Austria and Styria | |

| Parent house | House of Eticho (?) |

| Country | |

List | |

| Etymology | Habsburg Castle |

|---|---|

| Founded | 11th century |

| Founder | Radbot of Klettgau |

| Current head | Karl von Habsburg (cognatic line) |

| Final ruler | Charles I of Austria (cognatic line) |

| Titles |

List | |

| Motto | A.E.I.O.U. and Viribus Unitis |

|---|---|

| Estate(s) |

|

| Cadet branches | Agnatic: (all are extinct) |

The House of Habsburg (/ˈhæpsbɜːrɡ/), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in English and also known as the House of Austria, is one of the most prominent and important dynasties in European history.

The house takes its name from Habsburg Castle, a fortress built in the 1020s in present-day Switzerland by Radbot of Klettgau, who named his fortress Habsburg. His grandson Otto II was the first to take the fortress name as his own, adding "Count of Habsburg" to his title. In 1273, Count Radbot's seventh-generation descendant, Rudolph of Habsburg, was elected King of the Romans. Taking advantage of the extinction of the Babenbergs and of his victory over Ottokar II of Bohemia at the battle on the Marchfeld in 1278, he appointed his sons as Dukes of Austria and moved the family's power base to Vienna, where the Habsburg dynasty gained the name of "House of Austria" and ruled until 1918.

The throne of the Holy Roman Empire was continuously occupied by the Habsburgs from 1440 until their extinction in the male line in 1740 and, after the death of Francis I, from 1765 until its dissolution in 1806. The house also produced kings of Bohemia, Hungary, Croatia, Spain, Portugal and Galicia-Lodomeria, with their respective colonies; rulers of several principalities in the Low Countries and Italy; and in the 19th century, emperors of Austria and of Austria-Hungary as well as one emperor of Mexico. The family split several times into parallel branches, most consequentially in the mid-16th century between its Spanish and Austrian branches following the abdication of Charles V. Although they ruled distinct territories, the different branches nevertheless maintained close relations and frequently intermarried.

Members of the Habsburg family oversee the Austrian branch of the Order of the Golden Fleece and the Imperial and Royal Order of Saint George. The current head of the family is Karl von Habsburg.

Name

The origins of Habsburg Castle's name are uncertain. There is disagreement on whether the name is derived from the High German Habichtsburg (hawk castle), or from the Middle High German word hab/hap meaning ford, as there is a river with a ford nearby. The first documented use of the name by the dynasty itself has been traced to the year 1108.

The Habsburg name was not continuously used by the family members, since they often emphasized their more prestigious princely titles. The dynasty was thus long known as the "House of Austria". Complementarily, in some circumstances the family members were identified by their place of birth. Charles V was known in his youth after his birthplace as Charles of Ghent. When he became king of Spain he was known as Charles of Spain, and after he was elected emperor, as Charles V (in French, Charles Quint).

In Spain, the dynasty was known as the Casa de Austria, including illegitimate sons such as John of Austria and John Joseph of Austria. The arms displayed in their simplest form were those of Austria, which the Habsburgs had made their own, at times impaled with the arms of the Duchy of Burgundy (ancient).

After Maria Theresa married Duke Francis Stephen of Lorraine, the idea of "Habsburg" as associated with ancestral Austrian rulership was used to show that the old dynasty continued as did all its inherited rights. When Francis I became Emperor of Austria, he adopted the old shield of Habsburg in his personal arms, together with Austria and Lorraine. This also reinforced the "Germanness" of the (French-speaking) Austrian Emperor and his claim to rule in Germany, not least against the Prussian Kings. Some younger sons who had no prospects of the throne were given the personal title of "count of Habsburg".

The surname of more recent members of the family such as Otto von Habsburg and Karl von Habsburg is taken to be "von Habsburg" or more completely "von Habsburg-Lothringen". Princes and members of the house use the tripartite arms adopted in the 18th century by Francis Stephen.

History

Counts of Habsburg

The progenitor of the House of Habsburg may have been Guntram the Rich, a count in the Breisgau who lived in the 10th century, and forthwith farther back as the medieval Adalrich, Duke of Alsace, from the Etichonids from which Habsburg derives. His grandson Radbot of Klettgau founded the Habsburg Castle. That castle was the family seat during most of the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries. Giovanni Thomas Marnavich in his book "Regiae Sanctitatis Illyricanae Faecunditas" dedicated to Ferdinand III, wrote that the House of Habsburg is descended from the Roman emperor Constantine the Great.

In the 12th century, the Habsburgs became increasingly associated with the Staufer Emperors, participating in the imperial court and the Emperor's military expeditions; Werner II, Count of Habsburg died fighting for Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa in Italy. This association helped them to inherit many domains as the Staufers caused the extinction of many dynasties, some of which the Habsburgs were heirs to. In 1198, Rudolf II, Count of Habsburg fully dedicated the dynasty to the Staufer cause by joining the Ghibellines and funded the Staufer emperor Frederick II's war for the throne in 1211. The emperor was made godfather to his newly born grandson, the future king Rudolf.

The Habsburgs expanded their influence through arranged marriages and by gaining political privileges, especially countship rights in Zürichgau, Aargau and Thurgau. In the 13th century, the house aimed its marriage policy at families in Upper Alsace and Swabia. They were also able to gain high positions in the church hierarchy for their members. Territorially, they often profited from the extinction of other noble families such as the House of Kyburg.

Pivot to Eastern Alpine Duchies

By the second half of the 13th century, count Rudolph IV (1218–1291) had become an influential territorial lord in the area between the Vosges Mountains and Lake Constance. On 1 October 1273, he was elected as a compromise candidate as King of the Romans and received the name Rudolph I of Germany. He then led a coalition against king Ottokar II of Bohemia who had taken advantage of the Great Interregnum in order to expand southwards, taking over the respective inheritances of the Babenberg (Austria, Styria, Savinja) and of the Spanheim (Carinthia and Carniola). In 1278, Rudolph and his allies defeated and killed Ottokar at the Battle of Marchfeld, and the lands he had acquired reverted to the German crown. With the Georgenberg Pact of 1286, Rudolph secured for his family the duchies of Austria and Styria. The southern portions of Ottokar's former realm, Carinthia, Carniola, and Savinja, went to Rudolph's allies from the House of Gorizia.

Following Rudolph's death in 1291, Albert I's assassination in 1308, and Frederick the Fair's failure to secure the German/Imperial crown for himself, the Habsburgs temporarily lost their supremacy in the Empire. In the early 14th century, they also focused on the Kingdom of Bohemia. After Václav III’s death on 4 August 1306, there were no male heirs remaining in the Přemyslid dynasty. Habsburg scion Rudolph I was then elected but only lasted a year. The Bohemian kingship was an elected position, and the Habsburgs were only able to secure it on a hereditary basis much later in 1626, following their submission of the Czech lands during the Thirty Years' War. After 1307, subsequent Habsburg attempts to gain the Bohemian crown were frustrated first by Henry of Bohemia (a member of the House of Gorizia) and then by the House of Luxembourg.

Instead, they were able to expand southwards: in 1311, they took over Savinja; after the death of Henry in 1335, they assumed power in Carniola and Carinthia; and in 1369, they succeeded his daughter Margaret in Tyrol. After the death of Albert III of Gorizia in 1374, they gained a foothold at Pazin in central Istria, followed by Trieste in 1382. Meanwhile, the original home territories of the Habsburgs in what is now Switzerland, including the Aargau with Habsburg Castle, were lost in the 14th century to the expanding Swiss Confederacy after the battles of Morgarten (1315) and Sempach (1386). Habsburg Castle itself was finally lost to the Swiss in 1415.

Albertinian / Leopoldian split and Imperial elections

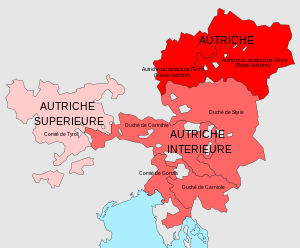

Rudolf IV's brothers Albert III and Leopold III ignored his efforts to preserve the integrity of the family domains, and enacted the separation of the so-called Albertinian and Leopoldian family lines on 25 September 1379 by the Treaty of Neuberg. The former would maintain Austria proper (then called Niederösterreich but comprising modern Lower Austria and most of Upper Austria), while the latter would rule over lands then labeled Oberösterreich, namely Inner Austria (Innerösterreich) comprising Styria, Carinthia and Carniola, and Further Austria (Vorderösterreich) consisting of Tyrol and the western Habsburg lands in Alsace and Swabia.

By marrying Elisabeth of Luxembourg, the daughter of Emperor Sigismund in 1437, Duke Albert V of the Albertine line (1397–1439) became the ruler of Bohemia and Hungary, again expanding the family's political horizons. The next year, Albert was crowned as King of the Romans, known as such as Albert II. Following his early death in a battle against the Ottomans in 1439 and that of his son Ladislaus Postumus in 1457, the Habsburgs lost Bohemia once more as well as Hungary, for several decades. However, with the extinction of the House of Celje in 1456 and the House of Wallsee-Enns in 1466/1483, they managed to absorb significant secular enclaves within their territories, and create a contiguous domain stretching from the border with Bohemia to the Adriatic sea.

After the death of Leopold's eldest son William in 1406, the Leopoldian line was further split among his brothers into the Inner Austrian territory under Ernest the Iron and a Tyrolean/Further Austrian line under Frederick of the Empty Pockets. In 1440, Ernest's son Frederick III was chosen by the electoral college to succeed Albert II as the king. Several Habsburg kings had attempted to gain the imperial dignity over the years, but success finally arrived on 19 March 1452, when Pope Nicholas V crowned Frederick III as the Holy Roman Emperor in a grand ceremony held in Rome. In Frederick III, the Pope found an important political ally with whose help he was able to counter the conciliar movement.

While in Rome, Frederick III married Eleanor of Portugal, enabling him to build a network of connections with dynasties in the west and southeast of Europe. Frederick was rather distant to his family; Eleanor, by contrast, had a great influence on the raising and education of Frederick's children and therefore played an important role in the family's rise to prominence. After Frederick III's coronation, the Habsburgs were able to hold the imperial throne almost continuously until 1806.

Archdukes

Through the forged document called privilegium maius (1358/59), Duke Rudolf IV (1339–1365) introduced the title of Archduke to place the Habsburgs on a par with the Prince-electors of the Empire, since Emperor Charles IV had omitted to give them the electoral dignity in his Golden Bull of 1356. Charles, however, refused to recognize the title, as did his immediate successors.

Duke Ernest the Iron and his descendants unilaterally assumed the title "archduke". That title was only officially recognized in 1453 by Emperor Frederick III, himself a Habsburg. Frederick himself used just "Duke of Austria", never Archduke, until his death in 1493. The title was first granted to Frederick's younger brother, Albert VI of Austria (died 1463), who used it at least from 1458. In 1477, Frederick granted the title archduke to his first cousin Sigismund of Austria, ruler of Further Austria. Frederick's son and heir, the future Emperor Maximilian I, apparently only started to use the title after the death of his wife Mary of Burgundy in 1482, as Archduke never appears in documents issued jointly by Maximilian and Mary as rulers in the Low Countries (where Maximilian is still titled "Duke of Austria"). The title appears first in documents issued under the joint rule of Maximilian and Philip (his under-age son) in the Low Countries.

Archduke was initially borne by those dynasts who ruled a Habsburg territory, i.e., only by males and their consorts, appanages being commonly distributed to cadets. These "junior" archdukes did not thereby become independent hereditary rulers, since all territories remained vested in the Austrian crown. Occasionally a territory might be combined with a separate gubernatorial mandate ruled by an archducal cadet. From the 16th century onward, archduke and its female form, archduchess, came to be used by all the members of the House of Habsburg (e.g., Queen Marie Antoinette of France was born Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria).

Re-unification and expansion

In 1457 Duke Frederick V of Inner Austria also gained the Austrian archduchy after his Albertine cousin Ladislaus the Posthumous had died without issue. 1490 saw the reunification of all Habsburg lines when Archduke Sigismund of Further Austria and Tyrol resigned in favor of Frederick's son Maximilian I.

As emperor, Frederick III took a leading role inside the family and positioned himself as the judge over the family's internal conflicts, often making use of the privilegium maius. He was able to restore the unity of the house's Austrian lands, as the Albertinian line was now extinct. Territorial integrity was also strengthened by the extinction of the Tyrolean branch of the Leopoldian line. Frederick's aim was to make Austria a united country, stretching from the Rhine to the Mur and Leitha.

On the external front, one of Frederick's main achievements was the Siege of Neuss (1474–75), in which he coerced Charles the Bold of Burgundy to give his daughter Mary of Burgundy as wife to Frederick's son Maximilian. The wedding took place on the evening of 16 August 1477 and ultimately resulted in the Habsburgs acquiring control of the Low Countries. After Mary's early death in 1482, Maximilian attempted to secure the Burgundian heritance to one of his and Mary's children Philip the Handsome. Charles VIII of France contested this, using both military and dynastic means, but the Burgundian succession was finally ruled in favor of Philip in the Treaty of Senlis in 1493.

After the death of his father in 1493, Maximilian was proclaimed the new King of the Romans, receiving the name Maximilian I. Maximilian was initially unable to travel to Rome to receive the Imperial title from the Pope, due to opposition from Venice and from the French who were occupying Milan, as well a refusal from the Pope due to enemy forces being present on his territory. In 1508, Maximilian proclaimed himself as the "chosen Emperor," and this was also recognized by the Pope due to changes in political alliances. This had a historical consequence in that, in the future, the Roman King would also automatically become Emperor, without needing the Pope's consent. Emperor Charles V would be the last to be crowned by the Pope himself, at Bologna in 1530.

Maximilian's rule (1493–1519) was a time of dramatic expansion for the Habsburgs. In 1497, Maximilian's son Philip, known as the Handsome or the Fair, married Joanna of Castile, also known as Joan the Mad, heiress of the Castile. Phillip and Joan had six children, the eldest of whom became Emperor Charles V and ruled the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon (including their colonies in the New World), Southern Italy, Austria, and the Low Countries in 1516, with his mother and nominal co-ruler Joanna, who was kept under confinement.

The foundations for the later empire of Austria-Hungary were laid in 1515 by the means of a double wedding between Louis, only son of Vladislaus II, King of Bohemia and Hungary, and Maximilian's granddaughter Mary; and between her brother Archduke Ferdinand and Louis's sister Anna. The wedding was celebrated in grand style on 22 July 1515. All these children were still minors, so the wedding was formally completed in 1521. Vladislaus died on 13 March 1516, and Maximilian died on 12 January 1519, but the latter's designs were ultimately successful: upon Louis's death in battle in 1526, Ferdinand became king of Bohemia and Hungary.

The Habsburg dynasty achieved its highest position when Charles V was elected Holy Roman Emperor. Much of Charles's reign was dedicated to the fight against Protestantism, which led to its eradication throughout vast areas under Habsburg control.

Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs

Charles formally became the sole monarch of Spain upon the death of his imprisoned mother Queen Joan in 1555.

After the abdication of Charles V in 1556, the Habsburg dynasty split into the branch of the Austrian (or German) Habsburgs, led by Ferdinand, and the branch of the Spanish Habsburgs, initially led by Charles's son Philip. Ferdinand I, King of Bohemia, Hungary, and archduke of Austria in the name of his brother Charles V became suo jure monarch as well as the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor (designated as successor already in 1531). Philip became King of Spain and its colonial empire as Philip II, and ruler of the Habsburg domains in Italy and the Low Countries. The Spanish Habsburgs also ruled Portugal for a time, known there as the Philippine dynasty (1580–1640).

The Seventeen Provinces and the Duchy of Milan were in personal union under the King of Spain, but remained part of the Holy Roman Empire. Furthermore, the Spanish king had claims on Hungary and Bohemia. In the secret Oñate treaty of 29 July 1617, the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs settled their mutual claims.

Habsburg inbreeding and extinction of the male lines

The Habsburgs sought to consolidate their power by frequent consanguineous marriages, resulting in a cumulatively deleterious effect on their gene pool. Health impairments due to inbreeding included epilepsy, insanity, and early death. A study of 3,000 family members over 16 generations by the University of Santiago de Compostela suggests inbreeding may have played a role in their extinction. Numerous members of the family showed specific facial deformities: an enlarged lower jaw with an extended chin known as mandibular prognathism or "Habsburg jaw", a large nose with hump and hanging tip ("Habsburg nose"), and an everted lower lip ("Habsburg lip"). The latter two are signs of maxillary deficiency. A 2019 study found that the degree of mandibular prognathism in the Habsburg family shows a statistically significant correlation with the degree of inbreeding. A correlation between maxillary deficiency and degree of inbreeding was also present but was not statistically significant. Other scientific studies, however, dispute the ideas of any linkage between fertility and consanguinity.

The gene pool eventually became so small that the last of the Spanish line, Charles II, who was severely disabled from birth (perhaps by genetic disorders) possessed a genome comparable to that of a child born to a brother and sister, as did his father, probably because of "remote inbreeding".

The death of Charles II of Spain in 1700 led to the War of the Spanish Succession, and that of Emperor Charles VI in 1740 led to the War of the Austrian Succession. In the former, the House of Bourbon won the conflict and put a final end to the Habsburg rule in Spain. The latter, however, was won by Maria Theresa and led to the succession of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine (German: Haus Habsburg-Lothringen) becoming the new main branch of the dynasty, in the person of Maria Theresa's son, Joseph II. This new House was created by the marriage between Maria Theresa of Habsburg and Francis Stephan, Duke of Lorraine (both of them were great-grandchildren of Habsburg emperor Ferdinand III, but from different empresses) this new House being a cadet branch of the female line of the House of Habsburg and the male line of the House of Lorraine. It is thought that extensive intra-family marriages within Spanish and Austrian lines contributed to the extinction of the main line.

House of Habsburg-Lorraine

Kingdoms and countries of Austria-Hungary: Cisleithania (Empire of Austria): 1. Bohemia, 2. Bukovina, 3. Carinthia, 4. Carniola, 5. Dalmatia, 6. Galicia, 7. Küstenland, 8. Lower Austria, 9. Moravia, 10. Salzburg, 11. Silesia, 12. Styria, 13. Tirol, 14. Upper Austria, 15. Vorarlberg; Transleithania (Kingdom of Hungary): 16. Hungary proper 17. Croatia-Slavonia; 18. Bosnia and Herzegovina (Austro-Hungarian condominium) |

On 6 August 1806, Emperor Francis I dissolved the Holy Roman Empire under pressure from Napoleon's reorganization of Germany. In anticipation of the loss of his title of Holy Roman Emperor, Francis had declared himself hereditary Emperor of Austria (as Francis I) on 11 August 1804, three months after Napoleon had declared himself Emperor of the French on 18 May 1804.

Emperor Francis I of Austria used the official full list of titles: "We, Francis the First, by the grace of God, Emperor of Austria; King of Jerusalem, Hungary, Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia and Lodomeria; Archduke of Austria; Duke of Lorraine, Salzburg, Würzburg, Franconia, Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola; Grand Duke of Cracow; Grand Prince of Transylvania; Margrave of Moravia; Duke of Sandomir, Masovia, Lublin, Upper and Lower Silesia, Auschwitz and Zator, Teschen, and Friule; Prince of Berchtesgaden and Mergentheim; Princely Count of Habsburg, Gorizia, and Gradisca and of the Tyrol; and Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia and Istria".

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 created a real union, whereby the Kingdom of Hungary was granted co-equality with the Empire of Austria, that henceforth didn't include the Kingdom of Hungary as a crownland anymore. The Austrian and the Hungarian lands became independent entities enjoying equal status. Under this arrangement, the Hungarians referred to their ruler as king and never emperor (see k. u. k.). This prevailed until the Habsburgs' deposition from both Austria and Hungary in 1918 following defeat in World War I.

On 11 November 1918, with his empire collapsing around him, the last Habsburg ruler, Charles I of Austria (who also reigned as Charles IV of Hungary) issued a proclamation recognizing Austria's right to determine the future of the state and renouncing any role in state affairs. Two days later, he issued a separate proclamation for Hungary. Even though he did not officially abdicate, this is considered the end of the Habsburg dynasty.

In 1919, the new republican Austrian government subsequently passed a law banishing the Habsburgs from Austrian territory until they renounced all intentions of regaining the throne and accepted the status of private citizens. Charles made several attempts to regain the throne of Hungary, and in 1921 the Hungarian government passed a law that revoked Charles' rights and dethroned the Habsburgs. The Habsburgs did not formally abandon all hope of returning to power until Otto von Habsburg, the eldest son of Charles I, on 31 May 1961 renounced all claims to the throne.

In the interwar period, the House of Habsburg was a vehement opponent of National Socialism and Communism. In Germany, Adolf Hitler diametrically opposed the centuries-old Habsburg principles of largely allowing local communities under their rule to maintain traditional ethnic, religious and language practices, and he bristled with hatred against the Habsburg family. During the Second World War there was a strong Habsburg resistance movement in Central Europe, which was radically persecuted by the Nazis and the Gestapo. The unofficial leader of these groups was Otto von Habsburg, who campaigned against the Nazis and for a free Central Europe in France and the United States. Most of the resistance fighters, such as Heinrich Maier, who successfully passed on production sites and plans for V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks and aircraft to the Allies, were executed. The Habsburg family played a leading role in the fall of the Iron Curtain and the collapse of the Communist Eastern Bloc.

Multilingualism

As they accumulated crowns and titles, the Habsburgs developed a unique family tradition of multilingualism that evolved over the centuries. The Holy Roman Empire had been multilingual from the start, even though most of its emperors were native German speakers. The language issue within the Empire became gradually more salient as the non-religious use of Latin declined and that of national languages gained prominence during the High Middle Ages. Emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg was known to be fluent in Czech, French, German, Italian and Latin.

The last section of his Golden Bull of 1356 specifies that the Empire's secular prince-electors "should be instructed in the varieties of the different dialects and languages" and that "since they are expected in all likelihood to have naturally acquired the German language, and to have been taught it from their infancy, [they] shall be instructed in the grammar of the Italian and Slavic tongues, beginning with the seventh year of their age so that, before the fourteenth year of their age, they may be learned in the same". In the early 15th century, Strasbourg-based chronicler Jakob Twinger von Königshofen asserted that Charlemagne had mastered six languages, even though he had a preference for German.

In the early years of the family's ascendancy, neither Rudolf I nor Albert I appear to have spoken French. By contrast, Charles V of Habsburg is well known some having been fluent in several languages. He was native in French and also knew Dutch from his youth in Flanders. He later added some Castilian Spanish, which he was required to learn by the Castilian Cortes Generales. He could also speak some Basque, acquired by the influence of the Basque secretaries serving in the royal court. He gained a decent command of German following the Imperial election of 1519, though he never spoke it as well as French. A witticism sometimes attributed to Charles was: "I speak Spanish/Latin [depending on the source] to God, Italian to women, French to men and German to my horse."

Latin was the administrative language of the Empire until the aggressive promotion of German by Joseph II in the late 18th century, which was partly reversed by his successors. From the 16th century, most if not all Habsburgs spoke French as well as German, and many also spoke Italian. Ferdinand I, Maximilian II and Rudolf II addressed the Bohemian Assembly in Czech, even though it is not clear that they were fluent. By contrast, there is little evidence that later Habsburgs in the 17th and 18th centuries spoke Czech, with the probable exception of Ferdinand III who made several stays in Bohemia and appears to have spoken Czech while there. In the 19th century, Francis I had notions of Czech, and Ferdinand I spoke it decently.

Franz Joseph received a bilingual early education in French and German, then added Czech and Hungarian and later Italian and Polish. He also learned Latin and Greek. After the end of the Habsburg Monarchy, Otto von Habsburg was fluent in English, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese.

Burials

List of Habsburg rulers

The Habsburgs' monarchical positions included:

- Holy Roman Emperors (intermittently from 1273 until 1806) and Roman-German kings

- Rulers of Austria (as dukes from 1278 until 1453; as archdukes from 1453 and as emperors from 1804 until 1918)

- Kings of Bohemia (1306–1307, 1437–1439, 1453–1457, 1526–1918)

- Kings of Spain (1516–1700)

- Kings of Hungary and Croatia (1526–1918)

- King of England and Ireland (1554-1558)

- Kings of Portugal (1581–1640)

- Grand princes of Transylvania (1690–1867)

- Kings of Galicia and Lodomeria (1772–1918)

- Emperor of Mexico (1864–1867)

Ancestors

- Guntram the Rich (ca. 930–985 / 990) Father of: The chronology of the Muri Abbey, burial place of the early Habsburgs, written in the 11th century, states that Guntramnus Dives (Guntram the Rich), was the ancestor of the House of Habsburg. Many historians believe this indeed makes Guntram the progenitor of the House of Habsburg. However, this account was 200 years after the fact, and much about him and the origins of the Habsburgs is uncertain. If true, as Guntram was a member of the Etichonider family, it would link the Habsburg lineage to this family.

- Lanzelin of Altenburg (died 991). Besides Radbot, below, he had sons named Rudolph I, Wernher, and Landolf.

Before the Albertine/Leopoldine division

Counts

Before Rudolph rose to German king, the Habsburgs were Counts of Baden in what is today southwestern Germany and Switzerland.

- Radbot of Klettgau, built the Habsburg Castle (c. 985 – 1035). Besides Werner I, he had two other sons: Otto I, who would become Count of Sundgau in the Alsace, and Albrecht I. Founded the Muri Abbey, which became the first burial place of members of the House of Habsburg. It is possible that Radbot founded the castle Habichtsburg, the residence of the House of Habsburg, but another possible founder is Werner I.

- Werner I, Count of Habsburg (1025/1030–1096). Besides Otto II, there was another son, Albert II, who was reeve of Muri from 1111 to 1141 after the death of Otto II.

- Otto II of Habsburg; first to name himself as "of Habsburg" (died 1111) Father of:

- Werner II of Habsburg (around 1135; died 1167) Father of:

- Albrecht III of Habsburg (the Rich), died 1199. Under him, the Habsburg territories expanded to cover most of what is today the German-speaking part of Switzerland. Father of:

- Rudolph II of Habsburg (b. c. 1160, died 1232) Father of:

- Albrecht IV of Habsburg, (died 1239 / 1240); father of Rudolph IV of Habsburg, who would later become king Rudolph I of Germany. Between Albrecht IV and his brother Rudolph III, the Habsburg properties were split, with Albrecht keeping the Aargau and the western parts, the eastern parts going to Rudolph III. Albrecht IV was also a mutual ancestor of Sophia Chotek and of her husband Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Kings of the Romans

King of Bohemia

- Rudolph I, king of Bohemia 1306–1307

Dukes/Archdukes of Austria

- Rudolph II, son of Rudolph I, duke of Austria and Styria together with his brother 1282–1283, was dispossessed by his brother, who eventually would be murdered by one of Rudolph's sons.

- Albert I (Albrecht I), son of Rudolph I and brother of the above, duke from 1282 to 1308; was Holy Roman Emperor from 1298 to 1308. See also below.

- Rudolph III, the oldest son of Albert I, designated duke of Austria and Styria 1298–1307

- Frederick the Handsome (Friedrich der Schöne), brother of Rudolph III. Duke of Austria and Styria (with his brother Leopold I) from 1308 to 1330; officially co-regent of the emperor Louis IV since 1325, but never ruled.

- Leopold I, brother of the above, duke of Austria and Styria from 1308 to 1326.

- Albert II (Albrecht II), brother of the above, duke of Further Austria from 1326 to 1358, duke of Austria and Styria 1330–1358, duke of Carinthia after 1335.

- Otto the Jolly (der Fröhliche), brother of the above, duke of Austria and Styria 1330–1339 (together with his brother), duke of Carinthia after 1335.

- Rudolph IV the Founder (der Stifter), oldest son of Albert II. Duke of Austria and Styria 1358–1365, Duke of Tirol after 1363.

Division of Albertinian and Leopoldian lines

After the death of Rudolph IV, his brothers Albert III and Leopold III ruled the Habsburg possessions together from 1365 until 1379, when they split the territories in the Treaty of Neuberg, Albert keeping the Duchy of Austria and Leopold ruling over Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, the Windic March, Tirol, and Further Austria.

Kings of the Romans and Holy Roman Emperors (Albertinian line)

- Albert II, emperor 1438–1439 (never crowned)

- Frederick III, emperor 1440–1493

Kings of Hungary and Bohemia (Albertinian line)

- Albert, king of Hungary and Bohemia (1437–1439)

- Ladislaus V Posthumus, king of Hungary (1444–1457) and Bohemia (1453–1457)

Dukes of Austria (Albertinian line)

- Albert III (Albrecht III), duke of Austria until 1395, from 1386 (after the death of Leopold) until 1395 also ruled over the latter's possessions.

- Albert IV (Albrecht IV), duke of Austria 1395–1404, in conflict with Leopold IV.

- Albert V (Albrecht V), duke of Austria 1404–1439, Holy Roman Emperor from 1438 to 1439 as Albert II. See also below.

- Ladislaus Posthumus, son of the above, duke of Austria 1440–1457.

Dukes of Styria, Carinthia, Tyrol / Inner Austria (Leopoldian line)

- Leopold III, duke of Styria, Carinthia, Tyrol, and Further Austria until 1386, when he was killed in the Battle of Sempach.

- William (Wilhelm), son of the above, 1386–1406 duke in Inner Austria (Carinthia, Styria)

- Leopold IV, son of Leopold III, 1391 regent of Further Austria, 1395–1402 duke of Tyrol, after 1404 also duke of Austria, 1406–1411 duke of Inner Austria

Leopoldian-Inner Austrian sub-line

- Ernest the Iron (der Eiserne), 1406–1424 duke of Inner Austria, until 1411 together and competing with his brother Leopold IV.

- Frederick V (Friedrich), son of Ernst, became emperor Frederick III in 1440. He was duke of Inner Austria from 1424 on. Guardian of Sigismund 1439–1446 and of Ladislaus Posthumus 1440–1452. See also below.

- Albert VI (Albrecht VI), brother of the above, 1446–1463 regent of Further Austria, duke of Austria 1458–1463

- Ernestine line of Saxon princes, ancestor of George I of Great Britain-descended from sister of Frederick III; also Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse King of Finland 1918

Leopoldian-Tyrol sub-line

- Frederick IV (Friedrich), brother of Ernst, 1402–1439 duke of Tyrol and Further Austria

- Sigismund, also spelled Siegmund or Sigmund, 1439–1446 under the tutelage of the Frederick V above, then duke of Tyrol, and after the death of Albrecht VI in 1463 also duke of Further Austria.

Reunited Habsburgs until extinction of agnatic lines

Sigismund had no children and adopted Maximilian I, son of Emperor Frederick III. Under Maximilian, the possessions of the Habsburgs would be united again under one ruler, after he had re-conquered the Duchy of Austria after the death of Matthias Corvinus, who resided in Vienna and styled himself duke of Austria from 1485 to 1490.

Holy Roman Emperors, Archdukes of Austria

- Maximilian I, emperor 1508–1519

- Charles V, emperor 1519–1556, his arms are explained in an article about them

The abdications of Charles V in 1556 ended his formal authority over Ferdinand and made him suo jure ruler in Austria, Bohemia, Hungary, as well as Holy Roman Emperor.

- Ferdinand I, emperor 1556–1564

(→Family Tree)

(→Family Tree) - Maximilian II, emperor 1564–1576

- Rudolf II, emperor 1576–1612

- Matthias, emperor 1612–1619

Ferdinand's inheritance had been split in 1564 among his children, with Maximilian taking the Imperial crown and his younger brother Archduke Charles II ruling over Inner Austria (i.e. the Duchy of Styria, the Duchy of Carniola with March of Istria, the Duchy of Carinthia, the Princely County of Gorizia and Gradisca, and the Imperial City of Trieste, ruled from Graz). Charles's son and successor Ferdinand II in 1619 became Archduke of Austria and Holy Roman Emperor as well as King of Bohemia and Hungary in 1620. The Further Austrian/Tyrolean line of Ferdinand's brother Archduke Leopold V survived until the death of his son Sigismund Francis in 1665, whereafter their territories ultimately returned to common control with the other Austrian Habsburg lands. Inner Austrian stadtholders went on to rule until the days of Empress Maria Theresa in the 18th century.

- Ferdinand II, emperor 1619–1637

- Ferdinand III, emperor 1637–1657

(→Family Tree)

(→Family Tree) - Leopold I, emperor 1658–1705

- Josef I, emperor 1705–1711

- Charles VI, emperor 1711–1740

- Maria Theresa of Austria, Habsburg heiress and wife of emperor Francis I Stephen, reigned as Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary and Bohemia 1740–1780.

Kings of Spain, Kings of Portugal (Spanish Habsburgs)

Habsburg Spain was a personal union between the Crowns of Castile and Aragon; Aragon was itself divided into the Kingdoms of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Majorca, Naples, Sicily, Malta and Sardinia. From 1581, they were kings of Portugal until they renounced this title in the 1668 Treaty of Lisbon. They were also Dukes of Milan, Lord of the Americas, and holder of multiple titles from territories within the Habsburg Netherlands. A full listing can be seen here.

- Philip I of Castile the Handsome, first son of Maximilian I, founded the Spanish Habsburgs in 1496 by marrying Joanna the Mad,

daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella. Philip died in 1506, leaving the

thrones of Castile and Aragon to be inherited and united into the throne

of Spain by his son:

- Charles I 1516–1556, aka Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor; divided the House into Austrian and Spanish lines The meanings of his arms are analyzed here.

- Philip II the Prudent 1556–1598, also Philip I of Portugal 1581–1598 and Philip I of England with his wife Mary I of England 1554–1558. The meanings of his arms are analyzed here.

.

.

- Philip III the Pious also Philip II of Portugal 1598–1621

- Philip IV the Great 1621–1665, also Philip III of Portugal 1621–1640

- Charles II the Bewitched ("El Hechizado") 1665–1700

The War of the Spanish Succession took place after the extinction of the Spanish Habsburg line, to determine the inheritance of Charles II.

Kings of Hungary (Austrian Habsburgs)

- Ferdinand I, king of Hungary 1526–1564

- Maximilian I, king of Hungary 1563–1576

- Rudolf I, king of Hungary 1572–1608

- Matthias II, king of Hungary 1608–1619

- Ferdinand II, king of Hungary 1618–1637

- Ferdinand III, king of Hungary 1625–1657

- Ferdinand IV, king of Hungary 1647–1654

- Leopold I, king of Hungary 1655–1705

- Joseph I, king of Hungary 1687–1711

- Charles III, king of Hungary 1711–1740

- Maria Theresa, queen of Hungary 1741–1780

Kings of Bohemia (Austrian Habsburgs)

- Ferdinand I, king of Bohemia 1526–1564

- Maximilian I, king of Bohemia 1563–1576

- Rudolph II, king of Bohemia 1572–1611

- Matthias, king of Bohemia 1611–1618

- Ferdinand II, king of Bohemia 1620–1637

- Ferdinand III, king of Bohemia 1625/37–1657

- Ferdinand IV, king of Bohemia 1647–1654 (joint rule)

- Leopold I, king of Bohemia 1655–1705

- Joseph I, king of Bohemia 1687–1711

- Charles VI, king of Bohemia 1711–1740

- Maria Theresa, queen of Bohemia 1743–1780

Titular Dukes of Burgundy, Lords of the Netherlands

Charles the Bold controlled not only Burgundy (both dukedom and county) but also Flanders and the broader Burgundian Netherlands. Frederick III managed to secure the marriage of Charles's only daughter, Mary of Burgundy, to his son Maximilian. The wedding took place on the evening of 16 August 1477, after the death of Charles. Mary and the Habsburgs lost the Duchy of Burgundy to France, but managed to defend and hold onto the rest what became the 17 provinces of the Habsburg Netherlands. After Mary's death in 1482, Maximilian acted as regent for his son Philip the Handsome.

- Philip the Handsome (1482–1506)

- Charles V (1506–1555)

- Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy, regent (1507–1515) and (1519–1530)

- Mary of Hungary, dowager queen of Hungary, sister of Charles V, governor of the Netherlands, 1531–1555

- Margaret of Parma, illegitimate daughter of Charles V, Duchess of Parma, and mother of Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, governor 1559–1567

- Don John of Austria, illegitimate son of Charles V, victor of Lepanto, governor of the Netherlands, 1576–1578

- Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, son of Margaret of Parma, governor of the Netherlands, 1578–1592

The Netherlands were frequently governed directly by a regent or governor-general, who was a collateral member of the Habsburgs. By the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 Charles V combined the Netherlands into one administrative unit, to be inherited by his son Philip II. Charles effectively united the Netherlands as one entity. The Habsburgs controlled the 17 Provinces of the Netherlands until the Dutch Revolt in the second half of the 16th century, when they lost the seven northern Protestant provinces. They held onto the southern Catholic part (roughly modern Belgium and Luxembourg) as the Spanish and Austrian Netherlands until they were conquered by French Revolutionary armies in 1795. The one exception to this was the period of (1601–1621), when shortly before Philip II died on 13 September 1598, he renounced his rights to the Netherlands in favor of his daughter Isabella and her fiancé, Archduke Albert of Austria, a younger son of Emperor Maximilian II. The territories reverted to Spain on the death of Albert in 1621, as the couple had no surviving offspring, and Isabella acted as regent-governor until her death in 1633:

Habsburg-Lorraine

The War of the Austrian Succession took place after the extinction of the male line of the Austrian Habsburg line upon the death of Charles VI. The direct Habsburg line itself became totally extinct with the death of Maria Theresa of Austria, when it was followed by the House of Habsburg-Lorraine.

Holy Roman Emperors, Kings of Hungary and Bohemia, Archdukes of Austria (House of Habsburg-Lorraine, main line)

- Francis I Stephen, emperor 1745–1765

(→Family Tree)

(→Family Tree) - Joseph II, emperor 1765–1790

- Leopold II, emperor 1790–1792

(→Family Tree)

(→Family Tree) - Francis II, emperor 1792–1806

(→Family Tree)

(→Family Tree)

Queen Maria Christina of Austria of Spain, great-granddaughter of Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor above. Wife of Alfonso XII of Spain and mother of Alfonso XIII of the House of Bourbon. Alfonso XIII's wife Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg was descended from King George I of Great Britain from the Habsburg Leopold Line {above}.

The House of Habsburg-Lorraine retained Austria and attached possessions after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire; see below.

A son of Leopold II was Archduke Rainer of Austria whose wife was from the House of Savoy; a daughter Adelaide, Queen of Sardina was the wife of King Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont, Savoy, and Sardinia and King of Italy. Their Children married into the Royal Houses of Bonaparte; Saxe-Coburg and Gotha {Bragança} {Portugal}; Savoy {Spain}; and the Dukedoms of Montferrat and Chablis.

Emperors of Austria (House of Habsburg-Lorraine, main line)

- Francis I, Emperor of Austria 1804–1835: formerly Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor

(→Family Tree)

- Ferdinand I, Emperor of Austria 1835–1848

- Francis Joseph, Emperor of Austria 1848–1916.

- Charles I, Emperor of Austria 1916–1918. He died in exile in 1922. His wife was of the House of Bourbon-Parma.

Kings of Hungary (Habsburg-Lorraine)

- Joseph II, king of Hungary 1780–1790

- Leopold II, king of Hungary 1790–1792

- Francis, king of Hungary 1792–1835

- Ferdinand V, king of Hungary and Bohemia 1835–1848

- Francis Joseph I, king of Hungary 1867–1916

- Charles IV, king of Hungary 1916–1918

Kings of Bohemia (Habsburg-Lorraine)

- Joseph II, king of Bohemia 1780–1790

- Leopold II, king of Bohemia 1790–1792

- Francis II, king of Bohemia 1792–1835

- Ferdinand V, king of Bohemia 1835–1848

- Francis Joseph, king of Bohemia 1848–1916

- Charles I, king of Bohemia 1916–1918

Italian branches

Grand dukes of Tuscany (House of Habsburg-Lorraine)

- Francis Stephen 1737–1765 (later Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor)

Francis Stephen assigned the grand duchy of Tuscany to his second son Peter Leopold, who in turn assigned it to his second son upon his accession as Holy Roman Emperor. Tuscany remained the domain of this cadet branch of the family until Italian unification.

- Peter Leopold 1765–1790 (later Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor)

- Ferdinand III 1790–1800, 1814–1824 (→Family Tree)

- Leopold II 1824–1849, 1849–1859

- Ferdinand IV 1859–1860

Dukes of Modena (Austria-Este branch of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine)

The duchy of Modena was assigned to a minor branch of the family by the Congress of Vienna. It was lost to Italian unification. The Dukes named their line the House of Austria-Este, as they were descended from the daughter of the last D'Este Duke of Modena.

- Francis IV 1814–1831, 1831–1846 (→Family Tree)

- Francis V 1846–1848, 1849–1859

Duchess of Parma (House of Habsburg-Lorraine)

The duchy of Parma was likewise assigned to a Habsburg, but did not stay in the House long before succumbing to Italian unification. It was granted to the second wife of Napoleon I of France, Maria Luisa Duchess of Parma, a daughter of the Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, who was the mother of Napoleon II of France. Napoleon had divorced his wife Rose de Tascher de la Pagerie (better known to history as Josephine de Beauharnais) in her favor.

- Maria Luisa 1814–1847 (→Family Tree)

Other monarchies

King of England

- Philip II of Spain (Jure uxoris King, with Mary I of England 1554–1558)

Empress consort of Brazil and Queen consort of Portugal (House of Habsburg-Lorraine)

Dona Maria Leopoldina of Austria (22 January 1797 – 11 December 1826) was an archduchess of Austria, Empress consort of Brazil and Queen consort of Portugal.

Empress consort of France (House of Habsburg-Lorraine)

- Marie Louise of Austria 1810–1814

Emperor of Mexico (House of Habsburg-Lorraine)

Maximilian, the adventurous second son of Archduke Franz Karl, was invited as part of Napoleon III's manipulations to take the throne of Mexico, becoming Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico. The conservative Mexican nobility, as well as the clergy, supported this Second Mexican Empire. His consort, Charlotte of Belgium, a daughter of King Leopold I of Belgium and a princess of the House of Saxe-Coburg Gotha, encouraged her husband's acceptance of the Mexican crown and accompanied him as Empress Carlota of Mexico. The adventure did not end well. Maximilian was shot in Cerro de las Campanas, Querétaro, in 1867 by the republican forces of Benito Juárez.

- Maximilian I (1864–1867) (→Family Tree)

List of post-monarchical Habsburgs

Main Habsburg-Lorraine line

Charles I was expelled from his domains after World War I and the empire was abolished.

- Charles I (1918–1922) (→Family Tree)

- Otto von Habsburg (1922–2007)

- Zita of Bourbon-Parma, guardian (1922–1930)

- Karl von Habsburg (2007–present)

House of Habsburg-Tuscany

- Ferdinand IV 1860–1908

- Archduke Joseph Ferdinand, Prince of Tuscany (1908–1942)

- Archduke Peter Ferdinand, Prince of Tuscany (1942–1948)

- Archduke Gottfried, Prince of Tuscany (1948–1984)

- Archduke Leopold Franz, Prince of Tuscany (1984–1994)

- Archduke Sigismund Otto, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1994–present)

House of Habsburg-Este

- Francis V (1859–1875)

- Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este & Crown Prince of Austria-Hungary (1875–1914)

- Karl, Archduke of Austria-Este (1914–1917)

- Robert, Archduke of Austria-Este (1917–1996)

- Lorenz, Archduke of Austria-Este (1996–Present)