Oceanography (from Ancient Greek ὠκεανός (ōkeanós) 'ocean', and γραφή (graphḗ) 'writing'), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamics; plate tectonics and the geology of the sea floor; and fluxes of various chemical substances and physical properties within the ocean and across its boundaries. These diverse topics reflect multiple disciplines that oceanographers utilize to glean further knowledge of the world ocean, including astronomy, biology, chemistry, climatology, geography, geology, hydrology, meteorology and physics. Paleoceanography studies the history of the oceans in the geologic past. An oceanographer is a person who studies many matters concerned with oceans, including marine geology, physics, chemistry and biology.

History

Early history

Humans first acquired knowledge of the waves and currents of the seas and oceans in pre-historic times. Observations on tides were recorded by Aristotle and Strabo in 384–322 BC. Early exploration of the oceans was primarily for cartography and mainly limited to its surfaces and of the animals that fishermen brought up in nets, though depth soundings by lead line were taken.

The Portuguese campaign of Atlantic navigation is the earliest example of a systematic scientific large project, sustained over many decades, studying the currents and winds of the Atlantic.

The work of Pedro Nunes (1502–1578) is remembered in the navigation context for the determination of the loxodromic curve: the shortest course between two points on the surface of a sphere represented onto a two-dimensional map. When he published his "Treatise of the Sphere" (1537), mostly a commentated translation of earlier work by others, he included a treatise on geometrical and astronomic methods of navigation. There he states clearly that Portuguese navigations were not an adventurous endeavour:

"nam se fezeram indo a acertar: mas partiam os nossos mareantes muy ensinados e prouidos de estromentos e regras de astrologia e geometria que sam as cousas que os cosmographos ham dadar apercebidas (...) e leuaua cartas muy particularmente rumadas e na ja as de que os antigos vsauam" (were not done by chance: but our seafarers departed well taught and provided with instruments and rules of astrology (astronomy) and geometry which were matters the cosmographers would provide (...) and they took charts with exact routes and no longer those used by the ancient).

His credibility rests on being personally involved in the instruction of pilots and senior seafarers from 1527 onwards by Royal appointment, along with his recognized competence as mathematician and astronomer. The main problem in navigating back from the south of the Canary Islands (or south of Boujdour) by sail alone, is due to the change in the regime of winds and currents: the North Atlantic gyre and the Equatorial counter current will push south along the northwest bulge of Africa, while the uncertain winds where the Northeast trades meet the Southeast trades (the doldrums) leave a sailing ship to the mercy of the currents. Together, prevalent current and wind make northwards progress very difficult or impossible. It was to overcome this problem and clear the passage to India around Africa as a viable maritime trade route, that a systematic plan of exploration was devised by the Portuguese. The return route from regions south of the Canaries became the 'volta do largo' or 'volta do mar'. The 'rediscovery' of the Azores islands in 1427 is merely a reflection of the heightened strategic importance of the islands, now sitting on the return route from the western coast of Africa (sequentially called 'volta de Guiné' and 'volta da Mina'); and the references to the Sargasso Sea (also called at the time 'Mar da Baga'), to the west of the Azores, in 1436, reveals the western extent of the return route. This is necessary, under sail, to make use of the southeasterly and northeasterly winds away from the western coast of Africa, up to the northern latitudes where the westerly winds will bring the seafarers towards the western coasts of Europe.

The secrecy involving the Portuguese navigations, with the death penalty for the leaking of maps and routes, concentrated all sensitive records in the Royal Archives, completely destroyed by the Lisbon earthquake of 1775. However, the systematic nature of the Portuguese campaign, mapping the currents and winds of the Atlantic, is demonstrated by the understanding of the seasonal variations, with expeditions setting sail at different times of the year taking different routes to take account of seasonal predominate winds. This happens from as early as late 15th century and early 16th: Bartolomeu Dias followed the African coast on his way south in August 1487, while Vasco da Gama would take an open sea route from the latitude of Sierra Leone, spending 3 months in the open sea of the South Atlantic to profit from the southwards deflection of the southwesterly on the Brazilian side (and the Brazilian current going southward) - Gama departed in July 1497); and Pedro Alvares Cabral, departing March 1500) took an even larger arch to the west, from the latitude of Cape Verde, thus avoiding the summer monsoon (which would have blocked the route taken by Gama at the time he set sail). Furthermore, there were systematic expeditions pushing into the western Northern Atlantic (Teive, 1454; Vogado, 1462; Teles, 1474; Ulmo, 1486). The documents relating to the supplying of ships, and the ordering of sun declination tables for the southern Atlantic for as early as 1493–1496, all suggest a well-planned and systematic activity happening during the decade long period between Bartolomeu Dias finding the southern tip of Africa, and Gama's departure; additionally, there are indications of further travels by Bartolomeu Dias in the area. The most significant consequence of this systematic knowledge was the negotiation of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, moving the line of demarcation 270 leagues to the west (from 100 to 370 leagues west of the Azores), bringing what is now Brazil into the Portuguese area of domination. The knowledge gathered from open sea exploration allowed for the well-documented extended periods of sail without sight of land, not by accident but as pre-determined planned route; for example, 30 days for Bartolomeu Dias culminating on Mossel Bay, the 3 months Gama spent in the South Atlantic to use the Brazil current (southward), or the 29 days Cabral took from Cape Verde up to landing in Monte Pascoal, Brazil.

The Danish expedition to Arabia 1761–67 can be said to be the world's first oceanographic expedition, as the ship Grønland had on board a group of scientists, including naturalist Peter Forsskål, who was assigned an explicit task by the king, Frederik V, to study and describe the marine life in the open sea, including finding the cause of mareel, or milky seas. For this purpose, the expedition was equipped with nets and scrapers, specifically designed to collect samples from the open waters and the bottom at great depth.

Although Juan Ponce de León in 1513 first identified the Gulf Stream, and the current was well known to mariners, Benjamin Franklin made the first scientific study of it and gave it its name. Franklin measured water temperatures during several Atlantic crossings and correctly explained the Gulf Stream's cause. Franklin and Timothy Folger printed the first map of the Gulf Stream in 1769–1770.

Information on the currents of the Pacific Ocean was gathered by explorers of the late 18th century, including James Cook and Louis Antoine de Bougainville. James Rennell wrote the first scientific textbooks on oceanography, detailing the current flows of the Atlantic and Indian oceans. During a voyage around the Cape of Good Hope in 1777, he mapped "the banks and currents at the Lagullas". He was also the first to understand the nature of the intermittent current near the Isles of Scilly, (now known as Rennell's Current).

Sir James Clark Ross took the first modern sounding in deep sea in 1840, and Charles Darwin published a paper on reefs and the formation of atolls as a result of the second voyage of HMS Beagle in 1831–1836. Robert FitzRoy published a four-volume report of Beagle's three voyages. In 1841–1842 Edward Forbes undertook dredging in the Aegean Sea that founded marine ecology.

The first superintendent of the United States Naval Observatory (1842–1861), Matthew Fontaine Maury devoted his time to the study of marine meteorology, navigation, and charting prevailing winds and currents. His 1855 textbook Physical Geography of the Sea was one of the first comprehensive oceanography studies. Many nations sent oceanographic observations to Maury at the Naval Observatory, where he and his colleagues evaluated the information and distributed the results worldwide.

Modern oceanography

Knowledge of the oceans remained confined to the topmost few fathoms of the water and a small amount of the bottom, mainly in shallow areas. Almost nothing was known of the ocean depths. The British Royal Navy's efforts to chart all of the world's coastlines in the mid-19th century reinforced the vague idea that most of the ocean was very deep, although little more was known. As exploration ignited both popular and scientific interest in the polar regions and Africa, so too did the mysteries of the unexplored oceans.

The seminal event in the founding of the modern science of oceanography was the 1872–1876 Challenger expedition. As the first true oceanographic cruise, this expedition laid the groundwork for an entire academic and research discipline. In response to a recommendation from the Royal Society, the British Government announced in 1871 an expedition to explore world's oceans and conduct appropriate scientific investigation. Charles Wyville Thomson and Sir John Murray launched the Challenger expedition. Challenger, leased from the Royal Navy, was modified for scientific work and equipped with separate laboratories for natural history and chemistry. Under the scientific supervision of Thomson, Challenger travelled nearly 70,000 nautical miles (130,000 km) surveying and exploring. On her journey circumnavigating the globe, 492 deep sea soundings, 133 bottom dredges, 151 open water trawls and 263 serial water temperature observations were taken. Around 4,700 new species of marine life were discovered. The result was the Report Of The Scientific Results of the Exploring Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76. Murray, who supervised the publication, described the report as "the greatest advance in the knowledge of our planet since the celebrated discoveries of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries". He went on to found the academic discipline of oceanography at the University of Edinburgh, which remained the centre for oceanographic research well into the 20th century. Murray was the first to study marine trenches and in particular the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and map the sedimentary deposits in the oceans. He tried to map out the world's ocean currents based on salinity and temperature observations, and was the first to correctly understand the nature of coral reef development.

In the late 19th century, other Western nations also sent out scientific expeditions (as did private individuals and institutions). The first purpose-built oceanographic ship, Albatros, was built in 1882. In 1893, Fridtjof Nansen allowed his ship, Fram, to be frozen in the Arctic ice. This enabled him to obtain oceanographic, meteorological and astronomical data at a stationary spot over an extended period.

In 1881 the geographer John Francon Williams published a seminal book, Geography of the Oceans. Between 1907 and 1911 Otto Krümmel published the Handbuch der Ozeanographie, which became influential in awakening public interest in oceanography. The four-month 1910 North Atlantic expedition headed by John Murray and Johan Hjort was the most ambitious research oceanographic and marine zoological project ever mounted until then, and led to the classic 1912 book The Depths of the Ocean.

The first acoustic measurement of sea depth was made in 1914. Between 1925 and 1927 the "Meteor" expedition gathered 70,000 ocean depth measurements using an echo sounder, surveying the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

In 1934, Easter Ellen Cupp, the first woman to have earned a PhD (at Scripps) in the United States, completed a major work on diatoms that remained the standard taxonomy in the field until well after her death in 1999. In 1940, Cupp was let go from her position at Scripps. Sverdrup specifically commended Cupp as a conscientious and industrious worker and commented that his decision was no reflection on her ability as a scientist. Sverdrup used the instructor billet vacated by Cupp to employ Marston Sargent,a biologist studying marine algae, which was not a new research program at Scripps. Financial pressures did not prevent Sverdrup from retaining the services of two other young post-doctoral students, Walter Munk and Roger Revelle. Cupp's partner, Dorothy Rosenbury, found her a position teaching high school, where she remained for the rest of her career. (Russell, 2000)

Sverdrup, Johnson and Fleming published The Oceans in 1942, which was a major landmark. The Sea (in three volumes, covering physical oceanography, seawater and geology) edited by M.N. Hill was published in 1962, while Rhodes Fairbridge's Encyclopedia of Oceanography was published in 1966.

The Great Global Rift, running along the Mid Atlantic Ridge, was discovered by Maurice Ewing and Bruce Heezen in 1953 and mapped by Heezen and Marie Tharp using bathymetric data; in 1954 a mountain range under the Arctic Ocean was found by the Arctic Institute of the USSR. The theory of seafloor spreading was developed in 1960 by Harry Hammond Hess. The Ocean Drilling Program started in 1966. Deep-sea vents were discovered in 1977 by Jack Corliss and Robert Ballard in the submersible DSV Alvin.

In the 1950s, Auguste Piccard invented the bathyscaphe and used the bathyscaphe Trieste to investigate the ocean's depths. The United States nuclear submarine Nautilus made the first journey under the ice to the North Pole in 1958. In 1962 the FLIP (Floating Instrument Platform), a 355-foot (108 m) spar buoy, was first deployed.

In 1968, Tanya Atwater led the first all-woman oceanographic expedition. Until that time, gender policies restricted women oceanographers from participating in voyages to a significant extent.

From the 1970s, there has been much emphasis on the application of large scale computers to oceanography to allow numerical predictions of ocean conditions and as a part of overall environmental change prediction. Early techniques included analog computers (such as the Ishiguro Storm Surge Computer) generally now replaced by numerical methods (e.g. SLOSH.) An oceanographic buoy array was established in the Pacific to allow prediction of El Niño events.

1990 saw the start of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) which continued until 2002. Geosat seafloor mapping data became available in 1995.

Study of the oceans is critical to understanding shifts in Earth's energy balance along with related global and regional changes in climate, the biosphere and biogeochemistry. The atmosphere and ocean are linked because of evaporation and precipitation as well as thermal flux (and solar insolation). Recent studies have advanced knowledge on ocean acidification, ocean heat content, ocean currents, sea level rise, the oceanic carbon cycle, the water cycle, Arctic sea ice decline, coral bleaching, marine heatwaves, extreme weather, coastal erosion and many other phenomena in regards to ongoing climate change and climate feedbacks.

In general, understanding the world ocean through further scientific study enables better stewardship and sustainable utilization of Earth's resources. The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission reports that 1.7% of the total national research expenditure of its members is focused on ocean science.

Branches

The study of oceanography is divided into these five branches:

Biological oceanography

Biological oceanography investigates the ecology and biology of marine organisms in the context of the physical, chemical and geological characteristics of their ocean environment.

Chemical oceanography

Chemical oceanography is the study of the chemistry of the ocean. Whereas chemical oceanography is primarily occupied with the study and understanding of seawater properties and its changes, ocean chemistry focuses primarily on the geochemical cycles. The following is a central topic investigated by chemical oceanography.

Ocean acidification

Ocean acidification describes the decrease in ocean pH that is caused by anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions into the atmosphere. Seawater is slightly alkaline and had a preindustrial pH of about 8.2. More recently, anthropogenic activities have steadily increased the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere; about 30–40% of the added CO2 is absorbed by the oceans, forming carbonic acid and lowering the pH (now below 8.1) through ocean acidification. The pH is expected to reach 7.7 by the year 2100.

An important element for the skeletons of marine animals is calcium, but calcium carbonate becomes more soluble with pressure, so carbonate shells and skeletons dissolve below the carbonate compensation depth. Calcium carbonate becomes more soluble at lower pH, so ocean acidification is likely to affect marine organisms with calcareous shells, such as oysters, clams, sea urchins and corals, and the carbonate compensation depth will rise closer to the sea surface. Affected planktonic organisms will include pteropods, coccolithophorids and foraminifera, all important in the food chain. In tropical regions, corals are likely to be severely affected as they become less able to build their calcium carbonate skeletons, in turn adversely impacting other reef dwellers.

The current rate of ocean chemistry change seems to be unprecedented in Earth's geological history, making it unclear how well marine ecosystems will adapt to the shifting conditions of the near future. Of particular concern is the manner in which the combination of acidification with the expected additional stressors of higher ocean temperatures and lower oxygen levels will impact the seas.

Geological oceanography

Geological oceanography is the study of the geology of the ocean floor including plate tectonics and paleoceanography.

Physical oceanography

Physical oceanography studies the ocean's physical attributes including temperature-salinity structure, mixing, surface waves, internal waves, surface tides, internal tides, and currents. The following are central topics investigated by physical oceanography.

Seismic Oceanography

Ocean currents

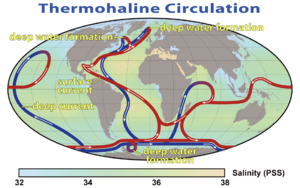

Since the early ocean expeditions in oceanography, a major interest was the study of ocean currents and temperature measurements. The tides, the Coriolis effect, changes in direction and strength of wind, salinity, and temperature are the main factors determining ocean currents. The thermohaline circulation (THC) (thermo- referring to temperature and -haline referring to salt content) connects the ocean basins and is primarily dependent on the density of sea water. It is becoming more common to refer to this system as the 'meridional overturning circulation' because it more accurately accounts for other driving factors beyond temperature and salinity.

- Examples of sustained currents are the Gulf Stream and the Kuroshio Current which are wind-driven western boundary currents.

Ocean heat content

Oceanic heat content (OHC) refers to the extra heat stored in the ocean from changes in Earth's energy balance. The increase in the ocean heat play an important role in sea level rise, because of thermal expansion. Ocean warming accounts for 90% of the energy accumulation associated with global warming since 1971.Paleoceanography

Paleoceanography is the study of the history of the oceans in the geologic past with regard to circulation, chemistry, biology, geology and patterns of sedimentation and biological productivity. Paleoceanographic studies using environment models and different proxies enable the scientific community to assess the role of the oceanic processes in the global climate by the reconstruction of past climate at various intervals. Paleoceanographic research is also intimately tied to palaeoclimatology.

Oceanographic institutions

The earliest international organizations of oceanography were founded at the turn of the 20th century, starting with the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea created in 1902, followed in 1919 by the Mediterranean Science Commission. Marine research institutes were already in existence, starting with the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples, Italy (1872), the Biological Station of Roscoff, France (1876), the Arago Laboratory in Banyuls-sur-mer, France (1882), the Laboratory of the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth, UK (1884), the Norwegian Institute for Marine Research in Bergen, Norway (1900), the Laboratory für internationale Meeresforschung, Kiel, Germany (1902). On the other side of the Atlantic, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography was founded in 1903, followed by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in 1930, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science in 1938, the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in 1949, and later the School of Oceanography at University of Washington. In Australia, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), established in 1972 soon became a key player in marine tropical research.

In 1921 the International Hydrographic Bureau, called since 1970 the International Hydrographic Organization, was established to develop hydrographic and nautical charting standards.