Whole genome sequencing (WGS), also known as full genome sequencing, complete genome sequencing, or entire genome sequencing, is the process of determining the entirety, or nearly the entirety, of the DNA sequence of an organism's genome at a single time. This entails sequencing all of an organism's chromosomal DNA as well as DNA contained in the mitochondria and, for plants, in the chloroplast.

Whole genome sequencing has largely been used as a research tool, but was being introduced to clinics in 2014. In the future of personalized medicine, whole genome sequence data may be an important tool to guide therapeutic intervention. The tool of gene sequencing at SNP level is also used to pinpoint functional variants from association studies and improve the knowledge available to researchers interested in evolutionary biology, and hence may lay the foundation for predicting disease susceptibility and drug response.

Whole genome sequencing should not be confused with DNA profiling,

which only determines the likelihood that genetic material came from a

particular individual or group, and does not contain additional

information on genetic relationships, origin or susceptibility to

specific diseases.

In addition, whole genome sequencing should not be confused with

methods that sequence specific subsets of the genome – such methods

include whole exome sequencing (1–2% of the genome) or SNP genotyping (< 0.1% of the genome).

History

The genome of the lab mouse

Mus musculus was published in 2002.

It took 10 years and 50 scientists spanning the globe to sequence the genome of

Elaeis guineensis (

oil palm). This genome was particularly difficult to sequence because it had many

repeated sequences which are difficult to organise.

The DNA sequencing methods used in the 1970s and 1980s were manual; for example, Maxam–Gilbert sequencing and Sanger sequencing.

Several whole bacteriophage and animal viral genomes were sequenced by

these techniques, but the shift to more rapid, automated sequencing

methods in the 1990s facilitated the sequencing of the larger bacterial

and eukaryotic genomes.

The first virus to have its complete genome sequenced was the Bacteriophage MS2 by 1976. In 1992, yeast chromosome III was the first chromosome of any organism to be fully sequenced. The first organism whose entire genome was fully sequenced was Haemophilus influenzae in 1995. After it, the genomes of other bacteria and some archaea were first sequenced, largely due to their small genome size. H. influenzae has a genome of 1,830,140 base pairs of DNA. In contrast, eukaryotes, both unicellular and multicellular such as Amoeba dubia and humans (Homo sapiens) respectively, have much larger genomes (see C-value paradox). Amoeba dubia has a genome of 700 billion nucleotide pairs spread across thousands of chromosomes. Humans contain fewer nucleotide pairs (about 3.2 billion in each germ cell – note the exact size of the human genome is still being revised) than A. dubia, however, their genome size far outweighs the genome size of individual bacteria.

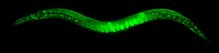

The first bacterial and archaeal genomes, including that of H. influenzae, were sequenced by Shotgun sequencing. In 1996 the first eukaryotic genome (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) was sequenced. S. cerevisiae, a model organism in biology has a genome of only around 12 million nucleotide pairs, and was the first unicellular eukaryote to have its whole genome sequenced. The first multicellular eukaryote, and animal, to have its whole genome sequenced was the nematode worm: Caenorhabditis elegans in 1998.

Eukaryotic genomes are sequenced by several methods including Shotgun

sequencing of short DNA fragments and sequencing of larger DNA clones

from DNA libraries such as bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) and yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs).

In 1999, the entire DNA sequence of human chromosome 22, the shortest human autosome, was published. By the year 2000, the second animal and second invertebrate (yet first insect) genome was sequenced – that of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster – a popular choice of model organism in experimental research. The first plant genome – that of the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana – was also fully sequenced by 2000. By 2001, a draft of the entire human genome sequence was published. The genome of the laboratory mouse Mus musculus was completed in 2002.

In 2004, the Human Genome Project published an incomplete version of the human genome. In 2008, a group from Leiden, the Netherlands, reported the sequencing of the first female human genome (Marjolein Kriek).

Currently thousands of genomes have been wholly or partially sequenced.

Experimental details

Cells used for sequencing

Almost any biological sample containing a full copy of the DNA—even a very small amount of DNA or ancient DNA—can provide the genetic material necessary for full genome sequencing. Such samples may include saliva, epithelial cells, bone marrow, hair (as long as the hair contains a hair follicle), seeds, plant leaves, or anything else that has DNA-containing cells.

The genome sequence of a single cell selected from a mixed population of cells can be determined using techniques of single cell genome sequencing.

This has important advantages in environmental microbiology in cases

where a single cell of a particular microorganism species can be

isolated from a mixed population by microscopy on the basis of its

morphological or other distinguishing characteristics. In such cases the

normally necessary steps of isolation and growth of the organism in

culture may be omitted, thus allowing the sequencing of a much greater

spectrum of organism genomes.

Single cell genome sequencing is being tested as a method of preimplantation genetic diagnosis, wherein a cell from the embryo created by in vitro fertilization is taken and analyzed before embryo transfer into the uterus. After implantation, cell-free fetal DNA can be taken by simple venipuncture from the mother and used for whole genome sequencing of the fetus.

Early techniques

An ABI PRISM 3100 genetic analyzer. Such capillary sequencers automated the early efforts of sequencing genomes.

Sequencing of nearly an entire human genome was first accomplished in 2000 partly through the use of shotgun sequencing technology. While full genome shotgun sequencing for small (4000–7000 base pair) genomes was already in use in 1979, broader application benefited from pairwise end sequencing, known colloquially as double-barrel shotgun sequencing.

As sequencing projects began to take on longer and more complicated

genomes, multiple groups began to realize that useful information could

be obtained by sequencing both ends of a fragment of DNA. Although

sequencing both ends of the same fragment and keeping track of the

paired data was more cumbersome than sequencing a single end of two

distinct fragments, the knowledge that the two sequences were oriented

in opposite directions and were about the length of a fragment apart

from each other was valuable in reconstructing the sequence of the

original target fragment.

The first published description of the use of paired ends was in 1990 as part of the sequencing of the human HPRT locus,

although the use of paired ends was limited to closing gaps after the

application of a traditional shotgun sequencing approach. The first

theoretical description of a pure pairwise end sequencing strategy,

assuming fragments of constant length, was in 1991. In 1995 the innovation of using fragments of varying sizes was introduced,

and demonstrated that a pure pairwise end-sequencing strategy would be

possible on large targets. The strategy was subsequently adopted by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) to sequence the entire genome of the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae in 1995, and then by Celera Genomics to sequence the entire fruit fly genome in 2000, and subsequently the entire human genome. Applied Biosystems, now called Life Technologies, manufactured the automated capillary sequencers utilized by both Celera Genomics and The Human Genome Project.

Current techniques

While capillary sequencing was the first approach to successfully

sequence a nearly full human genome, it is still too expensive and takes

too long for commercial purposes. Since 2005 capillary sequencing has

been progressively displaced by high-throughput (formerly "next-generation") sequencing technologies such as Illumina dye sequencing, pyrosequencing, and SMRT sequencing.

All of these technologies continue to employ the basic shotgun

strategy, namely, parallelization and template generation via genome

fragmentation.

Other technologies have emerged, including Nanopore technology. Though the sequencing accuracy of Nanopore technology is lower than those above, its read length is on average much longer. This generation of long reads is valuable especially in de novo whole-genome sequencing applications.

Analysis

In principle, full genome sequencing can provide the raw nucleotide

sequence of an individual organism's DNA at a single point in time.

However, further analysis must be performed to provide the biological or

medical meaning of this sequence, such as how this knowledge can be

used to help prevent disease. Methods for analyzing sequencing data are

being developed and refined.

Because sequencing generates a lot of data (for example, there are approximately six billion base pairs

in each human diploid genome), its output is stored electronically and

requires a large amount of computing power and storage capacity.

While analysis of WGS data can be slow, it is possible to speed up this step by using dedicated hardware.

Commercialization

Total cost of sequencing a whole human genome as calculated by the

NHGRI.

A number of public and private companies are competing to develop a

full genome sequencing platform that is commercially robust for both

research and clinical use, including Illumina, Knome, Sequenom,

454 Life Sciences, Pacific Biosciences, Complete Genomics,

Helicos Biosciences, GE Global Research (General Electric), Affymetrix, IBM, Intelligent Bio-Systems, Life Technologies, Oxford Nanopore Technologies, and the Beijing Genomics Institute. These companies are heavily financed and backed by venture capitalists, hedge funds, and investment banks.

A commonly-referenced commercial target for sequencing cost until the late 2010s was $1,000 USD, however, the private companies are working to reach a new target of only $100.

Incentive

In October 2006, the X Prize Foundation, working in collaboration with the J. Craig Venter Science Foundation, established the Archon X Prize for Genomics,

intending to award $10 million to "the first team that can build a

device and use it to sequence 100 human genomes within 10 days or less,

with an accuracy of no more than one error in every 1,000,000 bases

sequenced, with sequences accurately covering at least 98% of the

genome, and at a recurring cost of no more than $1,000 per genome". The Archon X Prize for Genomics was cancelled in 2013, before its official start date.

History

In 2007, Applied Biosystems started selling a new type of sequencer called SOLiD System. The technology allowed users to sequence 60 gigabases per run.

In June 2009, Illumina announced that they were launching their own Personal Full Genome Sequencing Service at a depth of 30× for $48,000 per genome. In August, the founder of Helicos Biosciences, Stephen Quake, stated that using the company's Single Molecule Sequencer he sequenced his own full genome for less than $50,000. In November, Complete Genomics published a peer-reviewed paper in Science demonstrating its ability to sequence a complete human genome for $1,700.

In May 2011, Illumina lowered its Full Genome Sequencing service to $5,000 per human genome, or $4,000 if ordering 50 or more.

Helicos Biosciences, Pacific Biosciences, Complete Genomics, Illumina,

Sequenom, ION Torrent Systems, Halcyon Molecular, NABsys, IBM, and GE

Global appear to all be going head to head in the race to commercialize

full genome sequencing.

With sequencing costs declining, a number of companies began

claiming that their equipment would soon achieve the $1,000 genome:

these companies included Life Technologies in January 2012, Oxford Nanopore Technologies in February 2012, and Illumina in February 2014. In 2015, the NHGRI estimated the cost of obtaining a whole-genome sequence at around $1,500. In 2016, Veritas Genetics began selling whole genome sequencing, including a report as to some of the information in the sequencing for $999. In summer 2019 Veritas Genetics cut the cost for WGS to $599. In 2017, BGI began offering WGS for $600.

However, in 2015 some noted that effective use of whole gene sequencing can cost considerably more than $1000. Also, reportedly there remain parts of the human genome that have not been fully sequenced by 2017.

Comparison with other technologies

DNA microarrays

Full genome sequencing provides information on a genome that is orders of magnitude larger than by DNA arrays, the previous leader in genotyping technology.

For humans, DNA arrays currently provide genotypic information on up to one million genetic variants,

while full genome sequencing will provide information on all six

billion bases in the human genome, or 3,000 times more data. Because of

this, full genome sequencing is considered a disruptive innovation

to the DNA array markets as the accuracy of both range from 99.98% to

99.999% (in non-repetitive DNA regions) and their consumables cost of

$5000 per 6 billion base pairs is competitive (for some applications)

with DNA arrays ($500 per 1 million basepairs).

Applications

Mutation frequencies

Whole genome sequencing has established the mutation

frequency for whole human genomes. The mutation frequency in the whole

genome between generations for humans (parent to child) is about 70 new

mutations per generation.

An even lower level of variation was found comparing whole genome

sequencing in blood cells for a pair of monozygotic (identical twins)

100-year-old centenarians. Only 8 somatic differences were found, though somatic variation occurring in less than 20% of blood cells would be undetected.

In the specifically protein coding regions of the human genome,

it is estimated that there are about 0.35 mutations that would change

the protein sequence between parent/child generations (less than one

mutated protein per generation).

In cancer, mutation frequencies are much higher, due to genome instability.

This frequency can further depend on patient age, exposure to DNA

damaging agents (such as UV-irradiation or components of tobacco smoke)

and the activity/inactivity of DNA repair mechanisms.

Furthermore, mutation frequency can vary between cancer types: in

germline cells, mutation rates occur at approximately 0.023 mutations

per megabase, but this number is much higher in breast cancer (1.18-1.66

somatic mutations per Mb), in lung cancer (17.7) or in melanomas (≈33). Since the haploid human genome consists of approximately 3,200 megabases, this translates into about 74 mutations (mostly in noncoding

regions) in germline DNA per generation, but 3,776-5,312 somatic

mutations per haploid genome in breast cancer, 56,640 in lung cancer and

105,600 in melanomas.

The distribution of somatic mutations across the human genome is very uneven,

such that the gene-rich, early-replicating regions receive fewer

mutations than gene-poor, late-replicating heterochromatin, likely due

to differential DNA repair activity. In particular, the histone modification H3K9me3 is associated with high, and H3K36me3 with low mutation frequencies.

Genome-wide association studies

In research, whole-genome sequencing can be used in a Genome-Wide

Association Study (GWAS) – a project aiming to determine the genetic

variant or variants associated with a disease or some other phenotype.

Diagnostic use

In 2009, Illumina released its first whole genome sequencers that were approved for clinical as opposed to research-only use and doctors at academic medical centers began quietly using them to try to diagnose what was wrong with people whom standard approaches had failed to help. In 2009, a team from Stanford led by Euan Ashley performed clinical interpretation of a full human genome, that of bioengineer Stephen Quake. In 2010, Ashley's team reported whole genome molecular autopsy

and in 2011, extended the interpretation framework to a fully sequenced

family, the West family, who were the first family to be sequenced on

the Illumina platform. The price to sequence a genome at that time was $19,500 USD,

which was billed to the patient but usually paid for out of a research

grant; one person at that time had applied for reimbursement from their

insurance company.

For example, one child had needed around 100 surgeries by the time he

was three years old, and his doctor turned to whole genome sequencing to

determine the problem; it took a team of around 30 people that included

12 bioinformatics

experts, three sequencing technicians, five physicians, two genetic

counsellors and two ethicists to identify a rare mutation in the XIAP that was causing widespread problems.

Due to recent cost reductions (see above) whole genome sequencing

has become a realistic application in DNA diagnostics. In 2013, the

3Gb-TEST consortium obtained funding from the European Union to prepare

the health care system for these innovations in DNA diagnostics. Quality assessment schemes, Health technology assessment and guidelines

have to be in place. The 3Gb-TEST consortium has identified the

analysis and interpretation of sequence data as the most complicated

step in the diagnostic process. At the Consortium meeting in Athens in September 2014, the Consortium coined the word genotranslation for this crucial step. This step leads to a so-called genoreport. Guidelines are needed to determine the required content of these reports.

Genomes2People (G2P), an initiative of Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School was created in 2011 to examine the integration of genomic sequencing into clinical care of adults and children. G2P's director, Robert C. Green,

had previously led the REVEAL study — Risk EValuation and Education for

Alzheimer's Disease – a series of clinical trials exploring patient

reactions to the knowledge of their genetic risk for Alzheimer's.

Green and a team of researchers launched the BabySeq Project in 2013 to

study the ethical and medical consequences of sequencing an infant's

DNA.

A second phase, BabySeq2, was funded by NIH in 2021 and is an

implementation study that expands this project, planning to enroll 500

infants from diverse families and track the effects of their genomic

sequencing on their pediatric care.

In 2018, researchers at Rady Children's Institute for Genomic

Medicine in San Diego, CA determined that rapid whole-genome sequencing

(rWGS) can diagnose genetic disorders in time to change acute medical or

surgical management (clinical utility) and improve outcomes in acutely

ill infants. The researchers reported a retrospective cohort study of

acutely ill inpatient infants in a regional children's hospital from

July 2016-March 2017. Forty-two families received rWGS for etiologic

diagnosis of genetic disorders. The diagnostic sensitivity of rWGS was

43% (eighteen of 42 infants) and 10% (four of 42 infants) for standard

genetic tests (P = .0005). The rate of clinical utility of rWGS (31%,

thirteen of 42 infants) was significantly greater than for standard

genetic tests (2%, one of 42; P = .0015). Eleven (26%) infants with

diagnostic rWGS avoided morbidity, one had a 43% reduction in likelihood

of mortality, and one started palliative care. In six of the eleven

infants, the changes in management reduced inpatient cost by

$800,000-$2,000,000. These findings replicate a prior study of the

clinical utility of rWGS in acutely ill inpatient infants, and

demonstrate improved outcomes and net healthcare savings. rWGS merits

consideration as a first tier test in this setting.

A 2018 review of 36 publications found the cost for whole genome sequencing to range from $1,906 USD to $24,810 USD and have a wide variance in diagnostic yield from 17% to 73% depending on patient groups.

Rare variant association study

Whole genome sequencing studies enable the assessment of associations between complex traits and both coding and noncoding rare variants (minor allele frequency

(MAF) < 1%) across the genome. Single-variant analyses typically

have low power to identify associations with rare variants, and variant

set tests have been proposed to jointly test the effects of given sets

of multiple rare variants. SNP annotations

help to prioritize rare functional variants, and incorporating these

annotations can effectively boost the power of genetic association of

rare variants analysis of whole genome sequencing studies.

Some tools have been specifically developed to provide all-in-one rare

variant association analysis for whole-genome sequencing data, including

integration of genotype data and their functional annotations,

association analysis, result summary and visualization.

Meta-analysis of whole genome sequencing studies provides an

attractive solution to the problem of collecting large sample sizes for

discovering rare variants associated with complex phenotypes. Some

methods have been developed to enable functionally informed rare variant

association analysis in biobank-scale cohorts using efficient

approaches for summary statistic storage.

Oncology

In

this field, whole genome sequencing represents a great set of

improvements and challenges to be faced by the scientific community, as

it makes it possible to analyze, quantify and characterize circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the bloodstream. This serves as a basis for early cancer diagnosis, treatment selection and relapse monitoring, as well as for determining the mechanisms of resistance, metastasis and phylogenetic

patterns in the evolution of cancer. It can also help in the selection

of individualized treatments for patients suffering from this pathology

and observe how existing drugs are working during the progression of

treatment. Deep whole genome sequencing involves a subclonal

reconstruction based on ctDNA in plasma that allows for complete epigenomic and genomic profiling, showing the expression of circulating tumor DNA in each case.

Ethical concerns

The introduction of whole genome sequencing may have ethical implications.

On one hand, genetic testing can potentially diagnose preventable

diseases, both in the individual undergoing genetic testing and in their

relatives. On the other hand, genetic testing has potential downsides such as genetic discrimination, loss of anonymity, and psychological impacts such as discovery of non-paternity.

Some ethicists insist that the privacy of individuals undergoing genetic testing must be protected, and is of particular concern when minors undergo genetic testing.

Illumina's CEO, Jay Flatley, claimed in February 2009 that "by 2019 it

will have become routine to map infants' genes when they are born". This potential use of genome sequencing is highly controversial, as it runs counter to established ethical norms for predictive genetic testing of asymptomatic minors that have been well established in the fields of medical genetics and genetic counseling.

The traditional guidelines for genetic testing have been developed over

the course of several decades since it first became possible to test

for genetic markers associated with disease, prior to the advent of

cost-effective, comprehensive genetic screening.

When an individual undergoes whole genome sequencing, they reveal

information about not only their own DNA sequences, but also about

probable DNA sequences of their close genetic relatives. This information can further reveal useful predictive information about relatives' present and future health risks.

Hence, there are important questions about what obligations, if any,

are owed to the family members of the individuals who are undergoing

genetic testing. In Western/European society, tested individuals are

usually encouraged to share important information on any genetic

diagnoses with their close relatives, since the importance of the

genetic diagnosis for offspring and other close relatives is usually one

of the reasons for seeking a genetic testing in the first place.

Nevertheless, a major ethical dilemma can develop when the patients

refuse to share information on a diagnosis that is made for serious

genetic disorder that is highly preventable and where there is a high

risk to relatives carrying the same disease mutation. Under such

circumstances, the clinician may suspect that the relatives would rather

know of the diagnosis and hence the clinician can face a conflict of

interest with respect to patient-doctor confidentiality.

Privacy concerns can also arise when whole genome sequencing is

used in scientific research studies. Researchers often need to put

information on patient's genotypes and phenotypes into public scientific

databases, such as locus specific databases.

Although only anonymous patient data are submitted to locus specific

databases, patients might still be identifiable by their relatives in

the case of finding a rare disease or a rare missense mutation.

Public discussion around the introduction of advanced forensic

techniques (such as advanced familial searching using public DNA

ancestry websites and DNA phenotyping approaches) has been limited,

disjointed, and unfocused. As forensic genetics and medical genetics

converge toward genome sequencing, issues surrounding genetic data

become increasingly connected, and additional legal protections may need

to be established.

Public human genome sequences

First people with public genome sequences

The first nearly complete human genomes sequenced were two Americans of predominantly Northwestern European ancestry in 2007 (J. Craig Venter at 7.5-fold coverage, and James Watson at 7.4-fold). This was followed in 2008 by sequencing of an anonymous Han Chinese man (at 36-fold), a Yoruban man from Nigeria (at 30-fold), a female clinical geneticist (Marjolein Kriek) from the Netherlands (at 7 to 8-fold), and a female leukemia patient in her mid-50s (at 33 and 14-fold coverage for tumor and normal tissues). Steve Jobs was among the first 20 people to have their whole genome sequenced, reportedly for the cost of $100,000. As of June 2012, there were 69 nearly complete human genomes publicly available. In November 2013, a Spanish family made their personal genomics data publicly available under a Creative Commons public domain license. The work was led by Manuel Corpas and the data obtained by direct-to-consumer genetic testing with 23andMe and the Beijing Genomics Institute. This is believed to be the first such Public Genomics dataset for a whole family.

Databases

According to Science the major databases of whole genomes are:

| Biobank |

Completed whole genomes |

Release/access information

|

| UK Biobank |

200,000 |

Made available through a Web platform in November 2021, it is the

largest public dataset of whole genomes. The genomes are linked to

anonymized medical information and are made more accessible for

biomedical research than prior, less comprehensive datasets. 300,000

more genomes are set to be released in early 2023.

|

| Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine |

161,000 |

National Institutes of Health (NIH) requires project-specific consent

|

| Million Veteran Program |

125,000 |

Non–Veterans Affairs researchers get access in 2022

|

| Genomics England's 100,000 Genomes |

120,000 |

Researchers must join collaboration

|

| All of Us |

90,000 |

NIH expects to release by early 2022

|

Genomic coverage

In terms of genomic coverage and accuracy, whole genome sequencing can broadly be classified into either of the following:

- A draft sequence, covering approximately 90% of the genome at approximately 99.9% accuracy

- A finished sequence, covering more than 95% of the genome at approximately 99.99% accuracy

Producing a truly high-quality finished sequence by this definition is very expensive. Thus, most human "whole genome sequencing" results are draft sequences (sometimes above and sometimes below the accuracy defined above).