From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

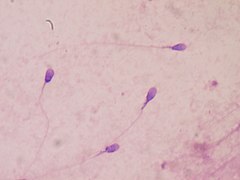

Sperm competition is the competitive process between spermatozoa of two or more different males to fertilize the same egg during sexual reproduction.

Competition can occur when females have multiple potential mating

partners. Greater choice and variety of mates increases a female's

chance to produce more viable offspring.

However, multiple mates for a female means each individual male has

decreased chances of producing offspring.

Sperm competition is an evolutionary pressure on males, and has led to

the development of adaptations to increase males' chance of reproductive success. Sperm competition results in a sexual conflict of interest between males and females. Males have evolved several defensive tactics including: mate-guarding, mating plugs, and releasing toxic seminal substances to reduce female re-mating tendencies to cope with sperm competition.

Offensive tactics of sperm competition involve direct interference by

one male on the reproductive success of another male, for instance by

physically removing another male's sperm prior to mating with a female. For an example, see Gryllus bimaculatus.

Sperm competition is often compared to having tickets in a raffle;

a male has a better chance of winning (i.e. fathering offspring) the

more tickets he has (i.e. the more sperm he inseminates a female with).

However, sperm are not free to produce,

and as such males are predicted to produce sperm of a size and number

that will maximize their success in sperm competition. By making many

spermatozoa, males can buy more "raffle tickets", and it is thought that

selection for numerous sperm has contributed to the evolution of anisogamy with very small sperm (because of the energy trade-off between sperm size and number). Alternatively, a male may evolve faster sperm to enable his sperm to reach and fertilize the female's ovum first. Dozens of adaptations have been documented in males that help them succeed in sperm competition.

Defensive adaptations

Mate-guarding

is a defensive behavioral trait that occurs in response to sperm

competition; males try to prevent other males from approaching the

female (and/or vice versa) thus preventing their mate from engaging in

further copulations.

Precopulatory and postcopulatory mate-guarding occurs in insects,

lizards, birds and primates. Mate-guarding also exists in the fish

species Neolamprologus pulcher,

as some males try to "sneak" matings with females in the territory of

other males. In these instances, the males guard their female by keeping

her in close enough proximity so that if an opponent male shows up in

his territory he will be able to fight off the rival male which will

prevent the female from engaging in extra-pair copulation with the rival male.

Organisms with polygynous mating systems are controlled by one

dominant male. In this type of mating system, the male is able to mate

with more than one female in a community. The dominant males will reign over the community until another suitor steps up and overthrows him.

The current dominant male will defend his title as the dominant male

and he will also be defending the females he mates with and the

offspring he sires. The elephant seal falls into this category since he

can participate in bloody violent matches in order to protect his

community and defend his title as the alpha male.

If the alpha male is somehow overthrown by the newcomer, his children

will most likely be killed and the new alpha male will start over with

the females in the group so that his lineage can be passed on.

Strategic mate-guarding occurs when the male only guards the

female during her fertile periods. This strategy can be more effective

because it may allow the male to engage in both extra-pair paternity and

within-pair paternity.

This is also because it is energetically efficient for the male to

guard his mate at this time. There is a lot of energy that is expended

when a male is guarding his mate. For instance, in polygynous

mate-guarding systems, the energetic costs of males is defending their

title as alpha male of their community.

Fighting is very costly in regards to the amount of energy used to

guard their mate. These bouts can happen more than once which takes a

toll on the physical well-being of the male. Another cost of

mate-guarding in this type of mating system is the potential increase of

the spread of disease.

If one male has an STD, he can pass that on to the females that he's

copulating with, potentially resulting in a depletion of the harem. This

would be an energetic cost towards both sexes for the reason that

instead of using the energy for reproduction, they are redirecting it

towards ridding themselves of this illness. Some females also benefit

from polygyny because extra pair copulations in females increase the

genetic diversity with the community of that species. This occurs because the male is not able to watch over all of the females and some will become promiscuous.

Eventually, the male will not have proper nutrition, which makes the male unable to produce sperm.

For instance, male amphipods will deplete their reserves of glycogen

and triglycerides only to have it replenished after the male is done

guarding that mate.

Also, if the amount of energy intake does not equal the energy

expended, then this could be potentially fatal to the male. Males may

even have to travel long distances during the breeding season in order

to find a female which absolutely drain their energy supply. Studies

were conducted to compare the cost of foraging of fish that migrate and

animals that are residential. The studies concluded that fish that were

residential had fuller stomachs containing higher quality of prey

compared to their migrant counterparts.

With all of these energy costs that go along with guarding a mate,

timing is crucial so that the male can use the minimal amount of energy.

This is why it is more efficient for males to choose a mate during

their fertile periods. Also, males will be more likely to guard their mate when there is a high density of males in the proximity.

Sometimes, organisms put in all this time and planning into courting a

mate in order to copulate and she may not even be interested. There is a

risk of cuckoldry of some sort, since a rival male can successfully

court the female that the male originally courting her could not do.

However, there are benefits that are associated with

mate-guarding. In a mating- guarding system, both parties, male and

female, are able to directly and indirectly benefit from this. For

instance, females can indirectly benefit from being protected by a mate.

The females can appreciate a decrease in predation and harassment from

other males while being able to observe her male counterpart.

This will allow her to recognize particular traits that she finds

ideal so that she'll be able to find another male that emulates those

qualities. In polygynous relationships, the dominant male of the

community benefits because he has the best fertilization success.

Communities can include 30 up to 100 females and, compared to the other

males, will greatly increase his chances of mating success.

Males who have successfully courted a potential mate will attempt

to keep them out of sight of other males before copulation. One way

organisms accomplish this is to move the female to a new location.

Certain butterflies, after enticing the female, will pick her up and fly

her away from the vicinity of potential males.

In other insects, the males will release a pheromone in order to make

their mate unattractive to other males or the pheromone masks her scent

completely. Certain crickets will participate in a loud courtship until the female accepts his gesture and then it suddenly becomes silent.

Some insects, prior to mating, will assume tandem positions to their

mate or position themselves in a way to prevent other males from

attempting to mate with that female.

The male checkerspot butterfly has developed a clever method in order

to attract and guard a mate. He will situate himself near an area that

possesses valuable resources that the female needs. He will then drive

away any males that come near and this will greatly increase his chances

of copulation with any female that comes to that area.

In post-copulatory mate-guarding males are trying to prevent

other males from mating with the female that they have mated with

already. For example, male millipedes in Costa Rica will ride on the

back of their mate letting the other males know that she's taken. Japanese beetles will assume a tandem position to the female after copulation.

This can last up to several hours allowing him to ward off any rival

males giving his sperm a high chance to fertilize that female's egg.

These, and other, types of methods have the male playing defense by

protecting his mate. Elephant seals are known to engage in bloody

battles in order to retain their title as dominant male so that they are

able to mate with all the females in their community.

Copulatory plugs are frequently observed in insects, reptiles, some mammals, and spiders.

Copulatory plugs are inserted immediately after a male copulates with a

female, which reduce the possibility of fertilization by subsequent

copulations from another male, by physically blocking the transfer of

sperm. Bumblebee mating plugs, in addition to providing a physical barrier to further copulations, contain linoleic acid, which reduces re-mating tendencies of females. A species of Sonoran desert Drosophila, Drosophila mettleri,

uses copulatory plugs to enable males to control the sperm reserve

space females have available. This behavior ensures males with higher

mating success at the expense of female control of sperm (sperm

selection).

Similarly, Drosophila melanogaster males release toxic seminal fluids, known as ACPs (accessory gland proteins), from their accessory glands to impede the female from participating in future copulations.

These substances act as an anti-aphrodisiac causing a dejection of

subsequent copulations, and also stimulate ovulation and oogenesis. Seminal proteins can have a strong influence on reproduction, sufficient to manipulate female behavior and physiology.

Another strategy, known as sperm partitioning, occurs when males

conserve their limited supply of sperm by reducing the quantity of sperm

ejected. In Drosophila,

ejaculation amount during sequential copulations is reduced; this

results in half filled female sperm reserves following a single

copulatory event, but allows the male to mate with a larger number of

females without exhausting his supply of sperm. To facilitate sperm partitioning, some males have developed complex ways to store and deliver their sperm. In the blue headed wrasse, Thalassoma bifasciatum,

the sperm duct is sectioned into several small chambers that are

surrounded by a muscle that allows the male to regulate how much sperm

is released in one copulatory event.

A strategy common among insects is for males to participate in

prolonged copulations. By engaging in prolonged copulations, a male has

an increased opportunity to place more sperm within the female's

reproductive tract and prevent the female from copulating with other

males.

It has been found that some male mollies (Poecilia)

have developed deceptive social cues to combat sperm competition.

Focal males will direct sexual attention toward typically non-preferred

females when an audience of other males is present. This encourages the

males that are watching to attempt to mate with the non-preferred

female. This is done in an attempt to decrease mating attempts with

the female that the focal male prefers, hence decreasing sperm

competition.

Offensive adaptations

Offensive

adaptation behavior differs from defensive behavior because it involves

an attempt to ruin the chances of another male's opportunity in

succeeding in copulation by engaging in an act that tries to terminate

the fertilization success of the previous male. This offensive behavior is facilitated by the presence of certain traits, which are called armaments. An example of an armament are antlers. Further, the presence of an offensive trait sometimes serves as a status signal. The mere display of an armament can suffice to drive away the competition without engaging in a fight, hence saving energy.

A male on the offensive side of mate-guarding may terminate the guarding

male's chances at a successful insemination by brawling with the

guarding male to gain access to the female. In Drosophila,

males release seminal fluids that contain additional toxins like

pheromones and modified enzymes that are secreted by their accessory

glands intended to destroy the sperm that have already made their way

into the female's reproductive tract from a recent copulation. However, this proved to be wrong because Drosophila melanogaster seminal fluid can actually protect the sperm of other males. Based on the "last male precedence"

idea, some males can remove sperm from previous males by ejaculating

new sperm into the female; hindering successful insemination

opportunities of the previous male.

Mate choice

The "good sperm hypothesis" is very common in polyandrous mating systems.

The "good sperm hypothesis" suggests that a male's genetic makeup will

determine the level of his competitiveness in sperm competition. When a male has "good sperm" he is able to father more viable offspring than males that do not have the "good sperm" genes.

Females may select males that have these superior "good sperm" genes

because it means that their offspring will be more viable and will

inherit the "good sperm" genes which will increase their fitness levels

when their sperm competes.

Studies show that there is more to determining the

competitiveness of the sperm in sperm competition in addition to a

male's genetic makeup. A male's dietary intake will also affect sperm

competition. An adequate diet consisting of increased amounts of diet

and sometimes more specific ratio in certain species will optimize sperm

number and fertility. Amounts of protein and carbohydrate intake were

tested for its effects on sperm production and quality in adult fruit

flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Studies showed these flies need to

constantly ingest carbohydrates and water to survive, but protein is

also required to attain sexual maturity.

In addition, The Mediterranean fruit fly, male diet has been shown to

affect male mating success, copula duration, sperm transfer, and male

participation in leks.

These all require a good diet with nutrients for proper gamete

production as well as energy for activities, which includes

participation in leks.

In addition, protein and carbohydrate amounts were shown to have

an effect on sperm production and fertility in the speckled cockroach.

Holidic diets were used which allowed for specific protein and

carbohydrate measurements to be taken, giving it credibility. A direct

correlation was seen in sperm number and overall of food intake. More

specifically, optimal sperm production was measured at a 1:2 protein to

carbohydrate ratio. Sperm fertility was best at a similar protein to

carbohydrate ratio of 1:2. This close alignment largely factors in

determining male fertility in Nauphoeta cinerea.

Surprisingly, sperm viability was not affected by any change in diet or

diet ratios. It's hypothesized that sperm viability is more affected by

the genetic makeup, like in the "good sperm hypothesis". These ratios

and results are not consistent with many other species and even conflict

with some. It seems there can't be any conclusions on what type of diet

is needed to positively influence sperm competition but rather

understand that different diets do play a role in determining sperm

competition in mate choice.

Evolutionary consequences

One evolutionary response to sperm competition is the variety in penis morphology of many species. For example, the shape of the human penis may have been selectively shaped by sperm competition. The human penis may have been selected to displace seminal fluids implanted in the female reproductive tract by a rival male. Specifically, the shape of the coronal ridge may promote displacement of seminal fluid from a previous matinga thrusting action during sexual intercourse. A 2003 study by Gordon G. Gallup

and colleagues concluded that one evolutionary purpose of the thrusting

motion characteristic of intense intercourse is for the penis to

“upsuck” another man's semen before depositing its own.

Evolution to increase ejaculate volume in the presence of sperm competition has a consequence on testis size. Large testes

can produce more sperm required for larger ejaculates, and can be found

across the animal kingdom when sperm competition occurs.

Males with larger testes have been documented to achieve higher

reproductive success rates than males with smaller testes in male yellow pine chipmunks.

In chichlid fish, it has been found that increased sperm competition

can lead to evolved larger sperm numbers, sperm cell sizes, and sperm

swimming speeds.

In some insects and spiders, for instance Nephila fenestrate,

the male copulatory organ breaks off or tears off at the end of

copulation and remains within the female to serve as a copulatory plug. This broken genitalia is believed to be an evolutionary response to sperm competition. This damage to the male genitalia means that these males can only mate once.

Female choice for males with competitive sperm

Female factors can influence the result of sperm competition through a process known as "sperm choice".

Proteins present in the female reproductive tract or on the surface of

the ovum may influence which sperm succeeds in fertilizing the egg.

During sperm choice, females are able to discriminate and

differentially use the sperm from different males. One instance where

this is known to occur is inbreeding; females will preferentially use

the sperm from a more distantly related male than a close relative.

Post-copulatory inbreeding avoidance

Inbreeding ordinarily has negative fitness consequences (inbreeding depression),

and as a result species have evolved mechanisms to avoid inbreeding.

Inbreeding depression is considered to be due largely to the expression

of homozygous deleterious recessive mutations. Outcrossing between unrelated individuals ordinarily leads to the masking of deleterious recessive mutations in progeny.

Numerous inbreeding avoidance

mechanisms operating prior to mating have been described. However,

inbreeding avoidance mechanisms that operate subsequent to copulation

are less well known. In guppies,

a post-copulatory mechanism of inbreeding avoidance occurs based on

competition between sperm of rival males for achieving fertilization.

In competitions between sperm from an unrelated male and from a full

sibling male, a significant bias in paternity towards the unrelated male

was observed.

In vitro fertilization experiments in the mouse, provided evidence of sperm selection at the gametic level.

When sperm of sibling and non-sibling males were mixed, a

fertilization bias towards the sperm of the non-sibling males was

observed. The results were interpreted as egg-driven sperm selection

against related sperm.

Female fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) were mated with males of four different degrees of genetic relatedness in competition experiments. Sperm competitive ability was negatively correlated with relatedness.

Female crickets (Teleogryllus oceanicus)

appear to use post-copulatory mechanisms to avoid producing inbred

offspring. When mated to both a sibling and an unrelated male, females

bias paternity towards the unrelated male.

Empirical support

It has been found that because of female choice (see sexual selection), morphology of sperm in many species occurs in many variations to accommodate or combat (see sexual conflict) the morphology and physiology of the female reproductive tract.

However, it is difficult to understand the interplay between female

and male reproductive shape and structure that occurs within the female

reproductive tract after mating that allows for the competition of sperm. Polyandrous females mate with many male partners. Females of many species of arthropod, mollusk and other phyla have a specialized sperm-storage organ called the spermatheca in which the sperm of different males sometimes compete for increased reproductive success. Species of crickets, specifically Gryllus bimaculatus,

are known to exhibit polyandrous sexual selection. Males will invest

more in ejaculation when competitors are in the immediate environment of

the female.

Evidence exists that illustrates the ability of genetically

similar spermatozoa to cooperate so as to ensure the survival of their

counterparts thereby ensuring the implementation of their genotypes

towards fertilization. Cooperation confers a competitive advantage by

several means, some of these include incapacitation of other competing

sperm and aggregation of genetically similar spermatozoa into structures

that promote effective navigation of the female reproductive tract and

hence improve fertilization ability. Such characteristics lead to

morphological adaptations that suit the purposes of cooperative methods

during competition. For example, spermatozoa possessed by the wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus)

possess an apical hook which is used to attach to other spermatozoa to

form mobile trains that enhance motility through the female reproductive

tract.

Spermatozoa that fail to incorporate themselves into mobile trains are

less likely to engage in fertilization. Other evidence suggests no

link between sperm competition and sperm hook morphology.

Selection to produce more sperm can also select for the evolution of larger testes.

Relationships across species between the frequency of multiple mating

by females and male testis size are well documented across many groups

of animals. For example, among primates, female gorillas are relatively

monogamous, so gorillas have smaller testes than humans, which in turn have smaller testes than the highly promiscuous bonobos.

Male chimpanzees that live in a structured multi-male, multi-female

community, have large testicles to produce more sperm, therefore giving

him better odds to fertilize the female. Whereas the community of

gorillas consist of one alpha male and two or three females, when the

female gorillas are ready to mate, normally only the alpha male is their

partner.

Regarding sexual dimorphism

among primates, humans falls into an intermediate group with moderate

sex differences in body size but relatively large testes. This is a

typical pattern of primates where several males and females live

together in a group and the male faces an intermediate number of

challenges from other males compared to exclusive polygyny and monogamy but frequent sperm competition.

Other means of sperm competition could include improving the sperm itself or its packaging materials (spermatophore).

The male black-winged damselfly

provides a striking example of an adaptation to sperm competition.

Female black-winged damselflies are known to mate with several males

over the span of only a few hours and therefore possess a receptacle

known as a spermatheca

which stores the sperm. During the process of mating the male

damselfly will pump his abdomen up and down using his specially adapted

penis which acts as a scrub brush to remove the sperm of another male.

This method proves quite successful and the male damselfly has been

known to remove 90-100 percent of the competing sperm.

Male dunnocks (

Prunella modularis) peck at the female's cloaca, removing sperm of previous mates.

A similar strategy has been observed in the dunnock, a small bird. Before mating with the polyandrous female, the male dunnock pecks at the female's cloaca in order to peck out the sperm of the previous male suitor.

In the fly Dryomyza anilis, females mate with multiple males. It benefits the male to attempt to be the last one to mate with a given female.

This is because there seems to be a cumulative percentage increase in

fertilization for the final male, such that the eggs laid in the last

oviposition bout are the most successful.

A notion emerged in 1996 that in some species, including humans, a

significant fraction of sperm specialize in a manner such that they

cannot fertilize the egg but instead have the primary effect of stopping

the sperm from other males from reaching the egg, e.g. by killing them

with enzymes or by blocking their access. This type of sperm

specialization became known popularly as "kamikaze sperm" or "killer

sperm", but most follow-up studies to this popularized notion have

failed to confirm the initial papers on the matter. While there is also currently little evidence of killer sperm in any non-human animals certain snails have an infertile sperm morph ("parasperm") that contains lysozymes, leading to speculation that they might be able to degrade a rivals' sperm.

The parasitoid wasp Nasonia vitripennis,

mated females can choose whether or not to lay a fertilized egg (which

develops into a daughter) or an unfertilized egg (which develops into a

son), therefore females suffer a cost from mating, as repeated matings

constrain their ability to allocate sex in their offspring. The

behaviour of these kamikaze-sperm is referred to in academic literature as "sperm-blocking", using basketball as a metaphor.

Sperm competition has led to other adaptations such as larger ejaculates, prolonged copulation, deposition of a copulatory plug

to prevent the female re-mating, or the application of pheromones that

reduce the female's attractiveness.

The adaptation of sperm traits, such as length, viability and velocity

might be constrained by the influence of cytoplasmic DNA (e.g. mitochondrial DNA);

mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the mother only and it is thought

that this could represent a constraint in the evolution of sperm.