| Sensory nervous system | |

|---|---|

Typical sensory system: the visual system, illustrated by the classic Gray's FIG. 722– This scheme shows the flow of information from the eyes to the central connections of the optic nerves and optic tracts, to the visual cortex. Area V1 is the region of the brain which is engaged in vision. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | organa sensuum |

| TA98 | A15.0.00.000 |

| TA2 | 6729 |

| FMA | 78499 75259, 78499 |

The sensory nervous system is a part of the nervous system responsible for processing sensory information. A sensory system consists of sensory neurons (including the sensory receptor cells), neural pathways, and parts of the brain involved in sensory perception and interoception. Commonly recognized sensory systems are those for vision, hearing, touch, taste, smell, balance and visceral sensation. Sense organs are transducers that convert data from the outer physical world to the realm of the mind where people interpret the information, creating their perception of the world around them.

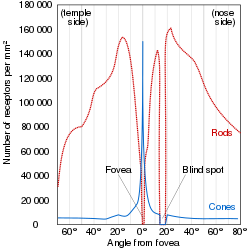

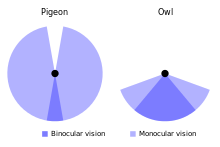

The receptive field is the area of the body or environment to which a receptor organ and receptor cells respond. For instance, the part of the world an eye can see, is its receptive field; the light that each rod or cone can see, is its receptive field. Receptive fields have been identified for the visual system, auditory system and somatosensory system.

Stimulus

- Organisms need information to solve at least three kinds of problems: (a) to maintain an appropriate environment, i.e., homeostasis; (b) to time activities (e.g., seasonal changes in behavior) or synchronize activities with those of conspecifics; and (c) to locate and respond to resources or threats (e.g., by moving towards resources or evading or attacking threats). Organisms also need to transmit information in order to influence another's behavior: to identify themselves, warn conspecifics of danger, coordinate activities, or deceive.

Sensory systems code for four aspects of a stimulus; type (modality), intensity, location, and duration. Arrival time of a sound pulse and phase differences of continuous sound are used for sound localization. Certain receptors are sensitive to certain types of stimuli (for example, different mechanoreceptors respond best to different kinds of touch stimuli, like sharp or blunt objects). Receptors send impulses in certain patterns to send information about the intensity of a stimulus (for example, how loud a sound is). The location of the receptor that is stimulated gives the brain information about the location of the stimulus (for example, stimulating a mechanoreceptor in a finger will send information to the brain about that finger). The duration of the stimulus (how long it lasts) is conveyed by firing patterns of receptors. These impulses are transmitted to the brain through afferent neurons.

Quiescent state

Most sensory systems have a quiescent state, that is, the state that a sensory system converges to when there is no input.

This is well-defined for a linear time-invariant system, whose input space is a vector space, and thus by definition has a point of zero. It is also well-defined for any passive sensory system, that is, a system that operates without needing input power. The quiescent state is the state the system converges to when there is no input power.

It is not always well-defined for nonlinear, nonpassive sensory organs, since they can't function without input energy. For example, a cochlea is not a passive organ, but actively vibrates its own sensory hairs to improve its sensitivity. This manifests as otoacoustic emissions in healthy ears, and tinnitus in pathological ears. There is still a quiescent state for the cochlea, since there is a well-defined mode of power input that it receives (vibratory energy on the eardrum), which provides an unambiguous definition of "zero input power".

Some sensory systems can have multiple quiescent states depending on its history, like flip-flops, and magnetic material with hysteresis. It can also adapt to different quiescent states. In complete darkness, the retinal cells become extremely sensitive, and there is noticeable "visual snow" caused by the retinal cells firing randomly without any light input. In brighter light, the retinal cells become a lot less sensitive, and consequently visual noise decreases.

Quiescent state is less well-defined when the sensory organ can be controlled by other systems, like a dog's ears that turn towards the front or the sides as the brain commands. Some spiders can use their nets as a large touch-organ, like weaving a skin for themselves. Even in the absence of anything falling on the net, hungry spiders may increase web thread tension, so as to respond promptly even to usually less noticeable, and less profitable prey, such as small fruit flies, creating two different "quiescent states" for the net.

Things become completely ill-defined for a system which connects its output to its own input, thus ever-moving without any external input. The prime example is the brain, with its default mode network.

Senses and receptors

While debate exists among neurologists as to the specific number of senses due to differing definitions of what constitutes a sense, Gautama Buddha and Aristotle classified five 'traditional' human senses which have become universally accepted: touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing. Other senses that have been well-accepted in most mammals, including humans, include nociception, equilibrioception, kinaesthesia, and thermoception. Furthermore, some nonhuman animals have been shown to possess alternate senses, including magnetoreception and electroreception.

Receptors

The initialization of sensation stems from the response of a specific receptor to a physical stimulus. The receptors which react to the stimulus and initiate the process of sensation are commonly characterized in four distinct categories: chemoreceptors, photoreceptors, mechanoreceptors, and thermoreceptors. All receptors receive distinct physical stimuli and transduce the signal into an electrical action potential. This action potential then travels along afferent neurons to specific brain regions where it is processed and interpreted.

Chemoreceptors

Chemoreceptors, or chemosensors, detect certain chemical stimuli and transduce that signal into an electrical action potential. The two primary types of chemoreceptors are:

- Distance chemoreceptors are integral to receiving stimuli in gases in the olfactory system through both olfactory receptor neurons and neurons in the vomeronasal organ.

- Direct chemoreceptors that detect stimuli in liquids include the taste buds in the gustatory system as well as receptors in the aortic bodies which detect changes in oxygen concentration.

Photoreceptors

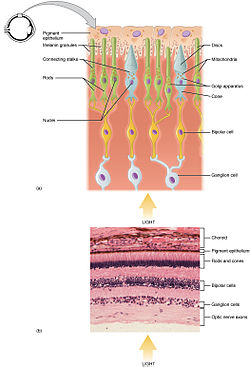

Photoreceptors are capable of phototransduction, a process which converts light (electromagnetic radiation) into, among other types of energy, a membrane potential. The three primary types of photoreceptors are: Cones are photoreceptors which respond significantly to color. In humans the three different types of cones correspond with a primary response to short wavelength (blue), medium wavelength (green), and long wavelength (yellow/red). Rods are photoreceptors which are very sensitive to the intensity of light, allowing for vision in dim lighting. The concentrations and ratio of rods to cones is strongly correlated with whether an animal is diurnal or nocturnal. In humans rods outnumber cones by approximately 20:1, while in nocturnal animals, such as the tawny owl, the ratio is closer to 1000:1. Ganglion Cells reside in the adrenal medulla and retina where they are involved in the sympathetic response. Of the ~1.3 million ganglion cells present in the retina, 1-2% are believed to be photosensitive ganglia. These photosensitive ganglia play a role in conscious vision for some animals, and are believed to do the same in humans.

Mechanoreceptors

Mechanoreceptors are sensory receptors which respond to mechanical forces, such as pressure or distortion. While mechanoreceptors are present in hair cells and play an integral role in the vestibular and auditory systems, the majority of mechanoreceptors are cutaneous and are grouped into four categories:

- Slowly adapting type 1 receptors have small receptive fields and respond to static stimulation. These receptors are primarily used in the sensations of form and roughness.

- Slowly adapting type 2 receptors have large receptive fields and respond to stretch. Similarly to type 1, they produce sustained responses to a continued stimuli.

- Rapidly adapting receptors have small receptive fields and underlie the perception of slip.

- Pacinian receptors have large receptive fields and are the predominant receptors for high-frequency vibration.

Thermoreceptors

Thermoreceptors are sensory receptors which respond to varying temperatures. While the mechanisms through which these receptors operate is unclear, recent discoveries have shown that mammals have at least two distinct types of thermoreceptors:

- The end-bulb of Krause, or bulboid corpuscle, detects temperatures above body temperature.

- Ruffini's end organ detects temperatures below body temperature.

TRPV1 is a heat-activated channel that acts as a small heat detecting thermometer in the membrane which begins the polarization of the neural fiber when exposed to changes in temperature. Ultimately, this allows us to detect ambient temperature in the warm/hot range. Similarly, the molecular cousin to TRPV1, TRPM8, is a cold-activated ion channel that responds to cold. Both cold and hot receptors are segregated by distinct subpopulations of sensory nerve fibers, which shows us that the information coming into the spinal cord is originally separate. Each sensory receptor has its own "labeled line" to convey a simple sensation experienced by the recipient. Ultimately, TRP channels act as thermosensors, channels that help us to detect changes in ambient temperatures.

Nociceptors

Nociceptors respond to potentially damaging stimuli by sending signals to the spinal cord and brain. This process, called nociception, usually causes the perception of pain. They are found in internal organs, as well as on the surface of the body. Nociceptors detect different kinds of damaging stimuli or actual damage. Those that only respond when tissues are damaged are known as "sleeping" or "silent" nociceptors.

- Thermal nociceptors are activated by noxious heat or cold at various temperatures.

- Mechanical nociceptors respond to excess pressure or mechanical deformation.

- Chemical nociceptors respond to a wide variety of chemicals, some of which are signs of tissue damage. They are involved in the detection of some spices in food.

Sensory cortex

All stimuli received by the receptors listed above are transduced to an action potential, which is carried along one or more afferent neurons towards a specific area of the brain. While the term sensory cortex is often used informally to refer to the somatosensory cortex, the term more accurately refers to the multiple areas of the brain at which senses are received to be processed. For the five traditional senses in humans, this includes the primary and secondary cortices of the different senses: the somatosensory cortex, the visual cortex, the auditory cortex, the primary olfactory cortex, and the gustatory cortex. Other modalities have corresponding sensory cortex areas as well, including the vestibular cortex for the sense of balance.

Somatosensory cortex

Located in the parietal lobe, the primary somatosensory cortex is the primary receptive area for the sense of touch and proprioception in the somatosensory system. This cortex is further divided into Brodmann areas 1, 2, and 3. Brodmann area 3 is considered the primary processing center of the somatosensory cortex as it receives significantly more input from the thalamus, has neurons highly responsive to somatosensory stimuli, and can evoke somatic sensations through electrical stimulation. Areas 1 and 2 receive most of their input from area 3. There are also pathways for proprioception (via the cerebellum), and motor control (via Brodmann area 4). See also: S2 Secondary somatosensory cortex.

Visual cortex

The visual cortex refers to the primary visual cortex, labeled V1 or Brodmann area 17, as well as the extrastriate visual cortical areas V2-V5. Located in the occipital lobe, V1 acts as the primary relay station for visual input, transmitting information to two primary pathways labeled the dorsal and ventral streams. The dorsal stream includes areas V2 and V5, and is used in interpreting visual 'where' and 'how.' The ventral stream includes areas V2 and V4, and is used in interpreting 'what.' Increases in Task-negative activity are observed in the ventral attention network, after abrupt changes in sensory stimuli, at the onset and offset of task blocks, and at the end of a completed trial.

Auditory cortex

Located in the temporal lobe, the auditory cortex is the primary receptive area for sound information. The auditory cortex is composed of Brodmann areas 41 and 42, also known as the anterior transverse temporal area 41 and the posterior transverse temporal area 42, respectively. Both areas act similarly and are integral in receiving and processing the signals transmitted from auditory receptors.

Primary olfactory cortex

Located in the temporal lobe, the primary olfactory cortex is the primary receptive area for olfaction, or smell. Unique to the olfactory and gustatory systems, at least in mammals, is the implementation of both peripheral and central mechanisms of action. The peripheral mechanisms involve olfactory receptor neurons which transduce a chemical signal along the olfactory nerve, which terminates in the olfactory bulb. The chemoreceptors in the receptor neurons that start the signal cascade are G protein-coupled receptors. The central mechanisms include the convergence of olfactory nerve axons into glomeruli in the olfactory bulb, where the signal is then transmitted to the anterior olfactory nucleus, the piriform cortex, the medial amygdala, and the entorhinal cortex, all of which make up the primary olfactory cortex.

In contrast to vision and hearing, the olfactory bulbs are not cross-hemispheric; the right bulb connects to the right hemisphere and the left bulb connects to the left hemisphere.

Gustatory cortex

The gustatory cortex is the primary receptive area for taste. The word taste is used in a technical sense to refer specifically to sensations coming from taste buds on the tongue. The five qualities of taste detected by the tongue include sourness, bitterness, sweetness, saltiness, and the protein taste quality, called umami. In contrast, the term flavor refers to the experience generated through integration of taste with smell and tactile information. The gustatory cortex consists of two primary structures: the anterior insula, located on the insular lobe, and the frontal operculum, located on the frontal lobe. Similarly to the olfactory cortex, the gustatory pathway operates through both peripheral and central mechanisms. Peripheral taste receptors, located on the tongue, soft palate, pharynx, and esophagus, transmit the received signal to primary sensory axons, where the signal is projected to the nucleus of the solitary tract in the medulla, or the gustatory nucleus of the solitary tract complex. The signal is then transmitted to the thalamus, which in turn projects the signal to several regions of the neocortex, including the gustatory cortex.

The neural processing of taste is affected at nearly every stage of processing by concurrent somatosensory information from the tongue, that is, mouthfeel. Scent, in contrast, is not combined with taste to create flavor until higher cortical processing regions, such as the insula and orbitofrontal cortex.

Human sensory system

The human sensory system consists of the following subsystems:

- Visual system

- Auditory system

- Somatosensory system consists of the receptors, transmitters (pathways) leading to S1, and S1 that experiences the sensations labelled as touch, pressure, vibration, temperature (warm or cold), pain (including itch and tickle), and the sensations of muscle movement and joint position including posture, movement, and facial expression (collectively also called proprioception)

- Gustatory system

- Olfactory system

- Vestibular system

- Interoceptive system

![Anatomy of a Rod Cell[4]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/Rod%26Cone.jpg/179px-Rod%26Cone.jpg)