| Insomnia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sleeplessness, trouble sleeping |

| |

| Depiction of insomnia from the 14th century medical manuscript Tacuinum Sanitatis | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, sleep medicine |

| Symptoms | Trouble sleeping, daytime sleepiness, low energy, irritability, depressed mood |

| Complications | Motor vehicle collisions |

| Causes | Unknown, psychological stress, chronic pain, heart failure, hyperthyroidism, heartburn, restless leg syndrome, others |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, sleep study |

| Differential diagnosis | Delayed sleep phase disorder, restless leg syndrome, sleep apnea, psychiatric disorder |

| Treatment | Sleep hygiene, cognitive behavioral therapy, sleeping pills |

| Frequency | ~20% |

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder in which people have trouble sleeping. They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep for as long as desired. Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low energy, irritability, and a depressed mood. It may result in an increased risk of motor vehicle collisions, as well as problems focusing and learning. Insomnia can be short term, lasting for days or weeks, or long term, lasting more than a month. The concept of the word insomnia has two possibilities: insomnia disorder and insomnia symptoms, and many abstracts of randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews often underreport on which of these two possibilities the word insomnia refers to.

Insomnia can occur independently or as a result of another problem. Conditions that can result in insomnia include psychological stress, chronic pain, heart failure, hyperthyroidism, heartburn, restless leg syndrome, menopause, certain medications, and drugs such as caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol. Other risk factors include working night shifts and sleep apnea. Diagnosis is based on sleep habits and an examination to look for underlying causes. A sleep study may be done to look for underlying sleep disorders. Screening may be done with two questions: "do you experience difficulty sleeping?" and "do you have difficulty falling or staying asleep?"

Although their efficacy as first line treatments is not unequivocally established, sleep hygiene and lifestyle changes are typically the first treatment for insomnia. Sleep hygiene includes a consistent bedtime, a quiet and dark room, exposure to sunlight during the day and regular exercise. Cognitive behavioral therapy may be added to this. While sleeping pills may help, they are sometimes associated with injuries, dementia, and addiction. These medications are not recommended for more than four or five weeks. The effectiveness and safety of alternative medicine is unclear.

Between 10% and 30% of adults have insomnia at any given point in time and up to half of people have insomnia in a given year. About 6% of people have insomnia that is not due to another problem and lasts for more than a month. People over the age of 65 are affected more often than younger people. Women are more often affected than males. Descriptions of insomnia occur at least as far back as ancient Greece.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of insomnia:

- Difficulty falling asleep, including difficulty finding a comfortable sleeping position

- Waking during the night, being unable to return to sleep and waking up early

- Not able to focus on daily tasks, difficulty in remembering

- Daytime sleepiness, irritability, depression or anxiety

- Feeling tired or having low energy during the day

- Trouble concentrating

- Being irritable, acting aggressive or impulsive

Sleep onset insomnia is difficulty falling asleep at the beginning of the night, often a symptom of anxiety disorders. Delayed sleep phase disorder can be misdiagnosed as insomnia, as sleep onset is delayed to much later than normal while awakening spills over into daylight hours.

It is common for patients who have difficulty falling asleep to also have nocturnal awakenings with difficulty returning to sleep. Two-thirds of these patients wake up in the middle of the night, with more than half having trouble falling back to sleep after a middle-of-the-night awakening.

Early morning awakening is an awakening occurring earlier (more than 30 minutes) than desired with an inability to go back to sleep, and before total sleep time reaches 6.5 hours. Early morning awakening is often a characteristic of depression. Anxiety symptoms may well lead to insomnia. Some of these symptoms include tension, compulsive worrying about the future, feeling overstimulated, and overanalyzing past events.

Poor sleep quality

Poor sleep quality can occur as a result of, for example, restless legs, sleep apnea or major depression. Poor sleep quality is defined as the individual not reaching stage 3 or delta sleep which has restorative properties.

Major depression leads to alterations in the function of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, causing excessive release of cortisol which can lead to poor sleep quality.

Nocturnal polyuria, excessive night-time urination, can also result in a poor quality of sleep.

Subjectivity

Some cases of insomnia are not really insomnia in the traditional sense, because people experiencing sleep state misperception often sleep for a normal amount of time. The problem is that, despite sleeping for multiple hours each night and typically not experiencing significant daytime sleepiness or other symptoms of sleep loss, they do not feel like they have slept very much, if at all. Because their perception of their sleep is incomplete, they incorrectly believe it takes them an abnormally long time to fall asleep, and they underestimate how long they stay asleep.

Causes

While insomnia can be caused by a number of conditions, it can also occur without any identifiable cause. This is known as Primary Insomnia. Primary Insomnia may also have an initial identifiable cause, but continues after the cause is no longer present. For example, a bout of insomnia may be triggered by a stressful work or life event. However the condition may continue after the stressful event has been resolved. In such cases, the insomnia is usually perpetuated by the anxiety or fear caused by the sleeplessness itself, rather than any external factors.

Symptoms of insomnia can be caused by or be associated with:

- Sleep breathing disorders, such as sleep apnea or upper airway resistance syndrome

- Use of psychoactive drugs (such as stimulants), including certain medications, herbs, caffeine, nicotine, cocaine, amphetamines, methylphenidate, aripiprazole, MDMA, modafinil, or excessive alcohol intake

- Use of or withdrawal from alcohol and other sedatives, such as anti-anxiety and sleep drugs like benzodiazepines

- Use of or withdrawal from pain-relievers such as opioids

- Heart disease

- Restless legs syndrome, which can cause sleep onset insomnia due to the discomforting sensations felt and the need to move the legs or other body parts to relieve these sensations

- Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), which occurs during sleep and can cause arousals of which the sleeper is unaware

- Pain: an injury or condition that causes pain can preclude an individual from finding a comfortable position in which to fall asleep, and can also cause awakening.

- Hormone shifts such as those that precede menstruation and those during menopause

- Life events such as fear, stress, anxiety, emotional or mental tension, work problems, financial stress, birth of a child, and bereavement

- Gastrointestinal issues such as heartburn or constipation

- Mental, neurobehavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders such as bipolar disorder, clinical depression, generalized anxiety disorder, post traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorder, autism, dementia, ADHD, and FASD

- Disturbances of the circadian rhythm, such as shift work and jet lag, can cause an inability to sleep at some times of the day and excessive sleepiness at other times of the day. Chronic circadian rhythm disorders are characterized by similar symptoms.

- Certain neurological disorders such as brain lesions, or a history of traumatic brain injury

- Medical conditions such as hyperthyroidism

- Abuse of over-the-counter or prescription sleep aids (sedative or depressant drugs) can produce rebound insomnia

- Poor sleep hygiene, e.g., noise or over-consumption of caffeine

- A rare genetic condition can cause a prion-based, permanent and eventually fatal form of insomnia called fatal familial insomnia

- Physical exercise: exercise-induced insomnia is common in athletes in the form of prolonged sleep onset latency

- Increased exposure to the blue light from artificial sources, such as phones or computers

- Chronic pain

- Lower back pain

- Asthma

Sleep studies using polysomnography have suggested that people who have sleep disruption have elevated night-time levels of circulating cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone. They also have an elevated metabolic rate, which does not occur in people who do not have insomnia but whose sleep is intentionally disrupted during a sleep study. Studies of brain metabolism using positron emission tomography (PET) scans indicate that people with insomnia have higher metabolic rates by night and by day. The question remains whether these changes are the causes or consequences of long-term insomnia.

Genetics

Heritability estimates of insomnia vary between 38% in males to 59% in females. A genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified 3 genomic loci and 7 genes that influence the risk of insomnia, and showed that insomnia is highly polygenic. In particular, a strong positive association was observed for the MEIS1 gene in both males and females. This study showed that the genetic architecture of insomnia strongly overlaps with psychiatric disorders and metabolic traits.

It has been hypothesized that epigenetics might also influence insomnia through a controlling process of both sleep regulation and brain-stress response having an impact as well on the brain plasticity.

Substance-induced

Alcohol-induced

Alcohol is often used as a form of self-treatment of insomnia to induce sleep. However, alcohol use to induce sleep can be a cause of insomnia. Long-term use of alcohol is associated with a decrease in NREM stage 3 and 4 sleep as well as suppression of REM sleep and REM sleep fragmentation. Frequent moving between sleep stages occurs with; awakenings due to headaches, the need to urinate, dehydration, and excessive sweating. Glutamine rebound also plays a role as when someone is drinking; alcohol inhibits glutamine, one of the body's natural stimulants. When the person stops drinking, the body tries to make up for lost time by producing more glutamine than it needs. The increase in glutamine levels stimulates the brain while the drinker is trying to sleep, keeping him/her from reaching the deepest levels of sleep. Stopping chronic alcohol use can also lead to severe insomnia with vivid dreams. During withdrawal, REM sleep is typically exaggerated as part of a rebound effect.

Benzodiazepine-induced

Like alcohol, benzodiazepines, such as alprazolam, clonazepam, lorazepam, and diazepam, are commonly used to treat insomnia in the short-term (both prescribed and self-medicated), but worsen sleep in the long-term. While benzodiazepines can put people to sleep (i.e., inhibit NREM stage 1 and 2 sleep), while asleep, the drugs disrupt sleep architecture: decreasing sleep time, delaying time to REM sleep, and decreasing deep slow-wave sleep (the most restorative part of sleep for both energy and mood).

Opioid-induced

Opioid medications such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, and morphine are used for insomnia that is associated with pain due to their analgesic properties and hypnotic effects. Opioids can fragment sleep and decrease REM and stage 2 sleep. By producing analgesia and sedation, opioids may be appropriate in carefully selected patients with pain-associated insomnia. However, dependence on opioids can lead to long-term sleep disturbances.

Risk factors

Insomnia affects people of all age groups but people in the following groups have a higher chance of acquiring insomnia:

- Individuals older than 60

- History of mental health disorder including depression, etc.

- Emotional stress

- Working late night shifts

- Traveling through different time zones

- Having chronic diseases such as diabetes, kidney disease, lung disease, Alzheimer's, or heart disease

- Alcohol or drug use disorders

- Gastrointestinal reflux disease

- Heavy smoking

- Work stress

Mechanism

Two main models exists as to the mechanism of insomnia, cognitive and physiological. The cognitive model suggests rumination and hyperarousal contribute to preventing a person from falling asleep and might lead to an episode of insomnia.

The physiological model is based upon three major findings in people with insomnia; firstly, increased urinary cortisol and catecholamines have been found suggesting increased activity of the HPA axis and arousal; second, increased global cerebral glucose utilization during wakefulness and NREM sleep in people with insomnia; and lastly, increased full body metabolism and heart rate in those with insomnia. All these findings taken together suggest a deregulation of the arousal system, cognitive system, and HPA axis all contributing to insomnia. However, it is unknown if the hyperarousal is a result of, or cause of insomnia. Altered levels of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA have been found, but the results have been inconsistent, and the implications of altered levels of such a ubiquitous neurotransmitter are unknown. Studies on whether insomnia is driven by circadian control over sleep or a wake dependent process have shown inconsistent results, but some literature suggests a deregulation of the circadian rhythm based on core temperature. Increased beta activity and decreased delta wave activity has been observed on electroencephalograms; however, the implication of this is unknown.

Around half of post-menopausal women experience sleep disturbances, and generally sleep disturbance is about twice as common in women as men; this appears to be due in part, but not completely, to changes in hormone levels, especially in and post-menopause.

Changes in sex hormones in both men and women as they age may account in part for increased prevalence of sleep disorders in older people.

Diagnosis

In medicine, insomnia is widely measured using the Athens insomnia scale. It is measured using eight different parameters related to sleep, finally represented as an overall scale which assesses an individual's sleep pattern.

A qualified sleep specialist should be consulted for the diagnosis of any sleep disorder so the appropriate measures can be taken. Past medical history and a physical examination need to be done to eliminate other conditions that could be the cause of insomnia. After all other conditions are ruled out a comprehensive sleep history should be taken. The sleep history should include sleep habits, medications (prescription and non-prescription), alcohol consumption, nicotine and caffeine intake, co-morbid illnesses, and sleep environment. A sleep diary can be used to keep track of the individual's sleep patterns. The diary should include time to bed, total sleep time, time to sleep onset, number of awakenings, use of medications, time of awakening, and subjective feelings in the morning. The sleep diary can be replaced or validated by the use of out-patient actigraphy for a week or more, using a non-invasive device that measures movement.

Workers who complain of insomnia should not routinely have polysomnography to screen for sleep disorders. This test may be indicated for patients with symptoms in addition to insomnia, including sleep apnea, obesity, a thick neck diameter, or high-risk fullness of the flesh in the oropharynx. Usually, the test is not needed to make a diagnosis, and insomnia especially for working people can often be treated by changing a job schedule to make time for sufficient sleep and by improving sleep hygiene.

Some patients may need to do an overnight sleep study to determine if insomnia is present. Such a study will commonly involve assessment tools including a polysomnogram and the multiple sleep latency test. Specialists in sleep medicine are qualified to diagnose disorders within the, according to the ICSD, 81 major sleep disorder diagnostic categories. Patients with some disorders, including delayed sleep phase disorder, are often mis-diagnosed with primary insomnia; when a person has trouble getting to sleep and awakening at desired times, but has a normal sleep pattern once asleep, a circadian rhythm disorder is a likely cause.

In many cases, insomnia is co-morbid with another disease, side-effects from medications, or a psychological problem. Approximately half of all diagnosed insomnia is related to psychiatric disorders. For those who have depression, "insomnia should be regarded as a co-morbid condition, rather than as a secondary one;" insomnia typically predates psychiatric symptoms. "In fact, it is possible that insomnia represents a significant risk for the development of a subsequent psychiatric disorder." Insomnia occurs in between 60% and 80% of people with depression. This may partly be due to treatment used for depression.

Determination of causation is not necessary for a diagnosis.

DSM-5 criteria

The DSM-5 criteria for insomnia include the following:

Predominant complaint of dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality, associated with one (or more) of the following symptoms:

- Difficulty initiating sleep. (In children, this may manifest as difficulty initiating sleep without caregiver intervention.)

- Difficulty maintaining sleep, characterized by frequent awakenings or problems returning to sleep after awakenings. (In children, this may manifest as difficulty returning to sleep without caregiver intervention.)

- Early-morning awakening with inability to return to sleep.

In addition:

- The sleep disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, educational, academic, behavioral, or other important areas of functioning.

- The sleep difficulty occurs at least three nights per week.

- The sleep difficulty is present for at least three months.

- The sleep difficulty occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep.

- The insomnia is not better explained by and does not occur exclusively during the course of another sleep-wake disorder (e.g., narcolepsy, a breathing-related sleep disorder, a circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorder, a parasomnia).

- The insomnia is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication).

Types

Insomnia can be classified as transient, acute, or chronic.

- Transient insomnia lasts for less than a week. It can be caused by another disorder, by changes in the sleep environment, by the timing of sleep, severe depression, or by stress. Its consequences – sleepiness and impaired psychomotor performance – are similar to those of sleep deprivation.

- Acute insomnia is the inability to consistently sleep well for a period of less than a month. Insomnia is present when there is difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or when the sleep that is obtained is non-refreshing or of poor quality. These problems occur despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep and they must result in problems with daytime function. Acute insomnia is also known as short term insomnia or stress related insomnia.

- Chronic insomnia lasts for longer than a month. It can be caused by another disorder, or it can be a primary disorder. Common causes of chronic insomnia include persistent stress, trauma, work schedules, poor sleep habits, medications, and other mental health disorders. People with high levels of stress hormones or shifts in the levels of cytokines are more likely than others to have chronic insomnia. Its effects can vary according to its causes. They might include muscular weariness, hallucinations, and/or mental fatigue.

Prevention

Prevention and treatment of insomnia may require a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy, medications, and lifestyle changes.

Among lifestyle practices, going to sleep and waking up at the same time each day can create a steady pattern which may help to prevent insomnia. Avoidance of vigorous exercise and caffeinated drinks a few hours before going to sleep is recommended, while exercise earlier in the day may be beneficial. Other practices to improve sleep hygiene may include:

- Avoiding or limiting naps

- Treating pain at bedtime

- Avoiding large meals, beverages, alcohol, and nicotine before bedtime

- Finding soothing ways to relax into sleep, including use of white noise

- Making the bedroom suitable for sleep by keeping it dark, cool, and free of devices, such as clocks, cell phones, or televisions

- Maintain regular exercise

- Try relaxing activities before sleeping

Management

It is recommended to rule out medical and psychological causes before deciding on the treatment for insomnia. Cognitive behavioral therapy is generally the first line treatment once this has been done. It has been found to be effective for chronic insomnia. The beneficial effects, in contrast to those produced by medications, may last well beyond the stopping of therapy.

Medications have been used mainly to reduce symptoms in insomnia of short duration; their role in the management of chronic insomnia remains unclear. Several different types of medications may be used. Many doctors do not recommend relying on prescription sleeping pills for long-term use. It is also important to identify and treat other medical conditions that may be contributing to insomnia, such as depression, breathing problems, and chronic pain. As of 2022, many people with insomnia were reported as not receiving overall sufficient sleep or treatment for insomnia.

Non-medication based

Non-medication based strategies have comparable efficacy to hypnotic medication for insomnia and they may have longer lasting effects. Hypnotic medication is only recommended for short-term use because dependence with rebound withdrawal effects upon discontinuation or tolerance can develop.

Non medication based strategies provide long lasting improvements to insomnia and are recommended as a first line and long-term strategy of management. Behavioral sleep medicine (BSM) tries to address insomnia with non-pharmacological treatments. The BSM strategies used to address chronic insomnia include attention to sleep hygiene, stimulus control, behavioral interventions, sleep-restriction therapy, paradoxical intention, patient education, and relaxation therapy. Some examples are keeping a journal, restricting the time spent awake in bed, practicing relaxation techniques, and maintaining a regular sleep schedule and a wake-up time. Behavioral therapy can assist a patient in developing new sleep behaviors to improve sleep quality and consolidation. Behavioral therapy may include, learning healthy sleep habits to promote sleep relaxation, undergoing light therapy to help with worry-reduction strategies and regulating the circadian clock.

Music may improve insomnia in adults (see music and sleep). EEG biofeedback has demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of insomnia with improvements in duration as well as quality of sleep. Self-help therapy (defined as a psychological therapy that can be worked through on one's own) may improve sleep quality for adults with insomnia to a small or moderate degree.

Stimulus control therapy is a treatment for patients who have conditioned themselves to associate the bed, or sleep in general, with a negative response. As stimulus control therapy involves taking steps to control the sleep environment, it is sometimes referred interchangeably with the concept of sleep hygiene. Examples of such environmental modifications include using the bed for sleep and sex only, not for activities such as reading or watching television; waking up at the same time every morning, including on weekends; going to bed only when sleepy and when there is a high likelihood that sleep will occur; leaving the bed and beginning an activity in another location if sleep does not occur in a reasonably brief period of time after getting into bed (commonly ~20 min); reducing the subjective effort and energy expended trying to fall asleep; avoiding exposure to bright light during night-time hours, and eliminating daytime naps.

A component of stimulus control therapy is sleep restriction, a technique that aims to match the time spent in bed with actual time spent asleep. This technique involves maintaining a strict sleep-wake schedule, sleeping only at certain times of the day and for specific amounts of time to induce mild sleep deprivation. Complete treatment usually lasts up to 3 weeks and involves making oneself sleep for only a minimum amount of time that they are actually capable of on average, and then, if capable (i.e. when sleep efficiency improves), slowly increasing this amount (~15 min) by going to bed earlier as the body attempts to reset its internal sleep clock. Bright light therapy may be effective for insomnia.

Paradoxical intention is a cognitive reframing technique where the insomniac, instead of attempting to fall asleep at night, makes every effort to stay awake (i.e. essentially stops trying to fall asleep). One theory that may explain the effectiveness of this method is that by not voluntarily making oneself go to sleep, it relieves the performance anxiety that arises from the need or requirement to fall asleep, which is meant to be a passive act. This technique has been shown to reduce sleep effort and performance anxiety and also lower subjective assessment of sleep-onset latency and overestimation of the sleep deficit (a quality found in many insomniacs).

Sleep hygiene

Sleep hygiene is a common term for all of the behaviors which relate to the promotion of good sleep. They include habits which provide a good foundation for sleep and help to prevent insomnia. However, sleep hygiene alone may not be adequate to address chronic insomnia. Sleep hygiene recommendations are typically included as one component of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). Recommendations include reducing caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol consumption, maximizing the regularity and efficiency of sleep episodes, minimizing medication usage and daytime napping, the promotion of regular exercise, and the facilitation of a positive sleep environment. The creation of a positive sleep environment may also be helpful in reducing the symptoms of insomnia. On the other hand, a systematic review by the AASM concluded that clinicians should not prescribe sleep hygiene for insomnia due to the evidence of absence of its efficacy and potential delaying of adequate treatment, recommending instead that effective therapies such as CBT-i should be preferred.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

There is some evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is superior in the long-term to benzodiazepines and the nonbenzodiazepines in the treatment and management of insomnia. In this therapy, patients are taught improved sleep habits and relieved of counter-productive assumptions about sleep. Common misconceptions and expectations that can be modified include:

- Unrealistic sleep expectations.

- Misconceptions about insomnia causes.

- Amplifying the consequences of insomnia.

- Performance anxiety after trying for so long to have a good night's sleep by controlling the sleep process.

Numerous studies have reported positive outcomes of combining cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia treatment with treatments such as stimulus control and the relaxation therapies. Hypnotic medications are equally effective in the short-term treatment of insomnia, but their effects wear off over time due to tolerance. The effects of CBT-I have sustained and lasting effects on treating insomnia long after therapy has been discontinued. The addition of hypnotic medications with CBT-I adds no benefit in insomnia. The long lasting benefits of a course of CBT-I shows superiority over pharmacological hypnotic drugs. Even in the short term when compared to short-term hypnotic medication such as zolpidem, CBT-I still shows significant superiority. Thus CBT-I is recommended as a first line treatment for insomnia.

Common forms of CBT-I treatments include stimulus control therapy, sleep restriction, sleep hygiene, improved sleeping environments, relaxation training, paradoxical intention, and biofeedback.

CBT is the well-accepted form of therapy for insomnia since it has no known adverse effects, whereas taking medications to alleviate insomnia symptoms have been shown to have adverse side effects. Nevertheless, the downside of CBT is that it may take a lot of time and motivation.

Acceptance and commitment therapy

Treatments based on the principles of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and metacognition have emerged as alternative approaches to treating insomnia. ACT rejects the idea that behavioral changes can help insomniacs achieve better sleep, since they require "sleep efforts" - actions which create more "struggle" and arouse the nervous system, leading to hyperarousal. The ACT approach posits that acceptance of the negative feelings associated with insomnia can, in time, create the right conditions for sleep. Mindfulness practice is a key feature of this approach, although mindfulness is not practised to induce sleep (this in itself is a sleep effort to be avoided) but rather as a longer-term activity to help calm the nervous system and create the internal conditions from which sleep can emerge.

A key distinction between CBT-i and ACT lies in the divergent approaches to time spent awake in bed. Proponents of CBT-i advocate minimizing time spent awake in bed, on the basis that this creates cognitive association between being in bed and wakefulness. The ACT approach proposes that avoiding time in bed may increase the pressure to sleep and arouse the nervous system further.

Research has shown that "ACT has a significant effect on primary and comorbid insomnia and sleep quality, and ... can be used as an appropriate treatment method to control and improve insomnia".

Internet interventions

Despite the therapeutic effectiveness and proven success of CBT, treatment availability is significantly limited by a lack of trained clinicians, poor geographical distribution of knowledgeable professionals, and expense. One way to potentially overcome these barriers is to use the Internet to deliver treatment, making this effective intervention more accessible and less costly. The Internet has already become a critical source of health-care and medical information. Although the vast majority of health websites provide general information, there is growing research literature on the development and evaluation of Internet interventions.

These online programs are typically behaviorally-based treatments that have been operationalized and transformed for delivery via the Internet. They are usually highly structured; automated or human supported; based on effective face-to-face treatment; personalized to the user; interactive; enhanced by graphics, animations, audio, and possibly video; and tailored to provide follow-up and feedback.

There is good evidence for the use of computer based CBT for insomnia.

Medications

Many people with insomnia use sleeping tablets and other sedatives. In some places medications are prescribed in over 95% of cases. They, however, are a second line treatment. In 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration stated it is going to require warnings for eszopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem, due to concerns about serious injuries resulting from abnormal sleep behaviors, including sleepwalking or driving a vehicle while asleep.

The percentage of adults using a prescription sleep aid increases with age. During 2005–2010, about 4% of U.S. adults aged 20 and over reported that they took prescription sleep aids in the past 30 days. Rates of use were lowest among the youngest age group (those aged 20–39) at about 2%, increased to 6% among those aged 50–59, and reached 7% among those aged 80 and over. More adult women (5%) reported using prescription sleep aids than adult men (3%). Non-Hispanic white adults reported higher use of sleep aids (5%) than non-Hispanic black (3%) and Mexican-American (2%) adults. No difference was shown between non-Hispanic black adults and Mexican-American adults in use of prescription sleep aids.

Antihistamines

As an alternative to taking prescription drugs, some evidence shows that an average person seeking short-term help may find relief by taking over-the-counter antihistamines such as diphenhydramine or doxylamine. Diphenhydramine and doxylamine are widely used in nonprescription sleep aids. They are the most effective over-the-counter sedatives currently available, at least in much of Europe, Canada, Australia, and the United States, and are more sedating than some prescription hypnotics. Antihistamine effectiveness for sleep may decrease over time, and anticholinergic side-effects (such as dry mouth) may also be a drawback with these particular drugs. While addiction does not seem to be an issue with this class of drugs, they can induce dependence and rebound effects upon abrupt cessation of use. However, people whose insomnia is caused by restless legs syndrome may have worsened symptoms with antihistamines.

Antidepressants

While insomnia is a common symptom of depression, antidepressants are effective for treating sleep problems whether or not they are associated with depression. While all antidepressants help regulate sleep, some antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, doxepin, mirtazapine, trazodone, and trimipramine, can have an immediate sedative effect, and are prescribed to treat insomnia. Amitriptyline, doxepin, and trimipramine all have antihistaminergic, anticholinergic, antiadrenergic, and antiserotonergic properties, which contribute to both their therapeutic effects and side effect profiles, while mirtazapine's actions are primarily antihistaminergic and antiserotonergic and trazodone's effects are primarily antiadrenergic and antiserotonergic. Mirtazapine is known to decrease sleep latency (i.e., the time it takes to fall asleep), promoting sleep efficiency and increasing the total amount of sleeping time in people with both depression and insomnia.

Agomelatine, a melatonergic antidepressant with claimed sleep-improving qualities that does not cause daytime drowsiness, is approved for the treatment of depression though not sleep conditions in the European Union and Australia. After trials in the United States, its development for use there was discontinued in October 2011 by Novartis, who had bought the rights to market it there from the European pharmaceutical company Servier.

A 2018 Cochrane review found the safety of taking antidepressants for insomnia to be uncertain with no evidence supporting long term use.

Melatonin agonists

Melatonin receptor agonists such as melatonin and ramelteon are used in the treatment of insomnia. The evidence for melatonin in treating insomnia is generally poor. There is low-quality evidence that it may speed the onset of sleep by 6 minutes. Ramelteon does not appear to speed the onset of sleep or the amount of sleep a person gets.

Usage of melatonin as a treatment for insomnia in adults has increased from 0.4% between 1999 and 2000 to nearly 2.1% between 2017 and 2018.

Most melatonin agonists have not been tested for longitudinal side effects. Prolonged-release melatonin may improve quality of sleep in older people with minimal side effects.

Studies have also shown that children who are on the autism spectrum or have learning disabilities, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or related neurological diseases can benefit from the use of melatonin. This is because they often have trouble sleeping due to their disorders. For example, children with ADHD tend to have trouble falling asleep because of their hyperactivity and, as a result, tend to be tired during most of the day. Another cause of insomnia in children with ADHD is the use of stimulants used to treat their disorder. Children who have ADHD then, as well as the other disorders mentioned, may be given melatonin before bedtime in order to help them sleep.

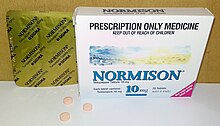

Benzodiazepines

The most commonly used class of hypnotics for insomnia are the benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines are not significantly better for insomnia than antidepressants. Chronic users of hypnotic medications for insomnia do not have better sleep than chronic insomniacs not taking medications. In fact, chronic users of hypnotic medications have more regular night-time awakenings than insomniacs not taking hypnotic medications. Many have concluded that these drugs cause an unjustifiable risk to the individual and to public health and lack evidence of long-term effectiveness. It is preferred that hypnotics be prescribed for only a few days at the lowest effective dose and avoided altogether wherever possible, especially in the elderly. Between 1993 and 2010, the prescribing of benzodiazepines to individuals with sleep disorders has decreased from 24% to 11% in the US, coinciding with the first release of nonbenzodiazepines.

The benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic medications also have a number of side-effects such as day time fatigue, motor vehicle crashes and other accidents, cognitive impairments, and falls and fractures. Elderly people are more sensitive to these side-effects. Some benzodiazepines have demonstrated effectiveness in sleep maintenance in the short term but in the longer term benzodiazepines can lead to tolerance, physical dependence, benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome upon discontinuation, and long-term worsening of sleep, especially after consistent usage over long periods of time. Benzodiazepines, while inducing unconsciousness, actually worsen sleep as – like alcohol – they promote light sleep while decreasing time spent in deep sleep. A further problem is, with regular use of short-acting sleep aids for insomnia, daytime rebound anxiety can emerge. Although there is little evidence for benefit of benzodiazepines in insomnia compared to other treatments and evidence of major harm, prescriptions have continued to increase. This is likely due to their addictive nature, both due to misuse and because – through their rapid action, tolerance and withdrawal they can "trick" insomniacs into thinking they are helping with sleep. There is a general awareness that long-term use of benzodiazepines for insomnia in most people is inappropriate and that a gradual withdrawal is usually beneficial due to the adverse effects associated with the long-term use of benzodiazepines and is recommended whenever possible.

Benzodiazepines all bind unselectively to the GABAA receptor. Some theorize that certain benzodiazepines (hypnotic benzodiazepines) have significantly higher activity at the α1 subunit of the GABAA receptor compared to other benzodiazepines (for example, triazolam and temazepam have significantly higher activity at the α1 subunit compared to alprazolam and diazepam, making them superior sedative-hypnotics – alprazolam and diazepam, in turn, have higher activity at the α2 subunit compared to triazolam and temazepam, making them superior anxiolytic agents). Modulation of the α1 subunit is associated with sedation, motor impairment, respiratory depression, amnesia, ataxia, and reinforcing behavior (drug-seeking behavior). Modulation of the α2 subunit is associated with anxiolytic activity and disinhibition. For this reason, certain benzodiazepines may be better suited to treat insomnia than others.

Z-Drugs

Nonbenzodiazepine or Z-drug sedative–hypnotic drugs, such as zolpidem, zaleplon, zopiclone, and eszopiclone, are a class of hypnotic medications that are similar to benzodiazepines in their mechanism of action, and indicated for mild to moderate insomnia. Their effectiveness at improving time to sleeping is slight, and they have similar—though potentially less severe—side effect profiles compared to benzodiazepines. Prescribing of nonbenzodiazepines has seen a general increase since their initial release on the US market in 1992, from 2.3% in 1993 among individuals with sleep disorders to 13.7% in 2010.

Orexin antagonists

Orexin receptor antagonists are a more recently introduced class of sleep medications and include suvorexant, lemborexant, and daridorexant, all of which are FDA-approved for treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulties with sleep onset and/or sleep maintenance.

Antipsychotics

Certain atypical antipsychotics, particularly quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone, are used in the treatment of insomnia. However, while common, use of antipsychotics for this indication is not recommended as the evidence does not demonstrate a benefit, and the risk of adverse effects are significant. A major 2022 systematic review and network meta-analysis of medications for insomnia in adults found that quetiapine did not demonstrate any short-term benefits for insomnia. Some of the more serious adverse effects may also occur at the low doses used, such as dyslipidemia and neutropenia. Such concerns of risks at low doses are supported by Danish observational studies that showed an association of use of low-dose quetiapine (excluding prescriptions filled for tablet strengths >50 mg) with an increased risk of major cardiovascular events as compared to use of Z-drugs, with most of the risk being driven by cardiovascular death. Laboratory data from an unpublished analysis of the same cohort also support the lack of dose-dependency of metabolic side effects, as new use of low-dose quetiapine was associated with a risk of increased fasting triglycerides at 1-year follow-up. Concerns regarding side effects are greater in the elderly.

Other sedatives

Gabapentinoids like gabapentin and pregabalin have sleep-promoting effects but are not commonly used for treatment of insomnia. Gabapentin is not effective in helping alcohol related insomnia.

Barbiturates, while once used, are no longer recommended for insomnia due to the risk of addiction and other side effects.

Comparative effectiveness

A major systematic review and network meta-analysis of medications for the treatment of insomnia was published in 2022. It found a wide range of effect sizes (standardized mean difference (SMD)) in terms of efficacy for insomnia. The assessed medications included benzodiazepines (SMDs 0.58 to 0.83), Z-drugs (SMDs 0.03 to 0.63), sedative antidepressants and antihistamines (SMDs 0.30 to 0.55), quetiapine (SMD 0.07), orexin receptor antagonists (SMDs 0.23 to 0.44), and melatonin receptor agonists (SMDs 0.00 to 0.13). The certainty of evidence varied and ranged from high to very low depending on the medication. The meta-analysis concluded that the orexin antagonist lemborexant and the Z-drug eszopiclone had the best profiles overall in terms of efficacy, tolerability, and acceptability.

Alternative medicine

Herbal products, such as valerian, kava, chamomile, and lavender, have been used to treat insomnia. However, there is no quality evidence that they are effective and safe. The same is true for cannabis and cannabinoids. It is likewise unclear if acupuncture is useful in the treatment of insomnia.

Prognosis

A survey of 1.1 million residents in the United States found that those that reported sleeping about 7 hours per night had the lowest rates of mortality, whereas those that slept for fewer than 6 hours or more than 8 hours had higher mortality rates. Severe insomnia – sleeping less than 3.5 hours in women and 4.5 hours in men – is associated with a 15% increase in mortality, while getting 8.5 or more hours of sleep per night was associated with a 15% higher mortality rate.

With this technique, it is difficult to distinguish lack of sleep caused by a disorder which is also a cause of premature death, versus a disorder which causes a lack of sleep, and the lack of sleep causing premature death. Most of the increase in mortality from severe insomnia was discounted after controlling for associated disorders. After controlling for sleep duration and insomnia, use of sleeping pills was also found to be associated with an increased mortality rate.

The lowest mortality was seen in individuals who slept between six and a half and seven and a half hours per night. Even sleeping only 4.5 hours per night is associated with very little increase in mortality. Thus, mild to moderate insomnia for most people is associated with increased longevity and severe insomnia is associated only with a very small effect on mortality. It is unclear why sleeping longer than 7.5 hours is associated with excess mortality.

Epidemiology

Between 10% and 30% of adults have insomnia at any given point in time and up to half of people have insomnia in a given year, making it the most common sleep disorder. About 6% of people have insomnia that is not due to another problem and lasts for more than a month. People over the age of 65 are affected more often than younger people. Females are more often affected than males. Insomnia is 40% more common in women than in men.

There are higher rates of insomnia reported among university students compared to the general population.

Society and culture

The word insomnia is from Latin: in + somnus "without sleep" and -ia as a nominalizing suffix.

The popular press have published stories about people who supposedly never sleep, such as that of Thái Ngọc and Al Herpin. Horne writes "everybody sleeps and needs to do so", and generally this appears true. However, he also relates from contemporary accounts the case of Paul Kern, who was shot in wartime and then "never slept again" until his death in 1943. Kern appears to be a completely isolated, unique case.