An out-of-body experience (OBE or sometimes OOBE) is a phenomenon in which a person perceives the world from a location outside their physical body. An OBE is a form of autoscopy (literally "seeing self"), although this term is more commonly used to refer to the pathological condition of seeing a second self, or doppelgänger.

The term out-of-body experience was introduced in 1943 by G. N. M. Tyrrell in his book Apparitions, and was adopted by researchers such as Celia Green, and Robert Monroe, as an alternative to belief-centric labels such as "astral projection" or "spirit walking". OBEs can be induced by traumatic brain injuries, sensory deprivation, near-death experiences, dissociative and psychedelic drugs, dehydration, sleep disorders, dreaming, and electrical stimulation of the brain, among other causes. It can also be deliberately induced by some. One in ten people has an OBE once, or more commonly, several times in their life.

Psychologists and neuroscientists regard OBEs as dissociative experiences occurring along different psychological and neurological factors.

Spontaneous OBEs

During/near sleep

Those experiencing OBEs sometimes report (among other types of immediate and spontaneous experience) a preceding and initiating lucid-dream state. In many cases, people who claim to have had an OBE report being on the verge of sleep, or being already asleep shortly before the experience. A large percentage of these cases refer to situations where the sleep was not particularly deep (due to illness, noises in other rooms, emotional stress, exhaustion from overworking, frequent re-awakening, etc.). In most of these cases subjects perceive themselves as being awake; about half of them note a feeling of sleep paralysis.

Near-death experiences

Another form of spontaneous OBE is the near-death experience (NDE). Some subjects report having had an OBE at times of severe physical trauma such as near-drownings or major surgery. Near-death experiences may include subjective impressions of being outside the physical body, sometimes visions of deceased relatives and religious figures, and transcendence of ego and spatiotemporal boundaries. The experience typically includes such factors as: a sense of being dead; a feeling of peace and painlessness; hearing of various non-physical sounds, an out-of-body experience; a tunnel experience (the sense of moving up or through a narrow passageway); encountering "beings of light" and a God-like figure or similar entities; being given a "life review", and a reluctance to return to life.

Resulting from extreme physical effort

Along the same lines as an NDE, extreme physical effort during activities such as high-altitude climbing and marathon running can induce OBEs. A sense of bilocation may be experienced, with both ground and air-based perspectives being experienced simultaneously.

Induced OBEs

Chemical

- OBEs can be induced by hallucinogens (particularly dissociatives) such as psilocybin, ketamine, DMT, MDA, and LSD.

Mental induction

- Falling asleep physically without losing awareness. The "Mind Awake, Body Asleep" state is widely suggested as a cause of OBEs, voluntary and otherwise. Thomas Edison used this state to tackle problems while working on his inventions. He would rest a silver dollar on his head while sitting with a metal bucket in a chair. As he drifted off, the coin would noisily fall into the bucket, restoring some of his alertness. OBE pioneer Sylvan Muldoon more simply used a forearm held perpendicular in bed as the falling object. Salvador Dalí was said to use a similar "paranoiac-critical" method to gain odd visions which inspired his paintings. Deliberately teetering between awake and asleep states is known to cause spontaneous trance episodes at the onset of sleep which are ultimately helpful when attempting to induce an OBE. By moving deeper and deeper into relaxation, one eventually encounters a "slipping" feeling if the mind is still alert. This slipping is reported to feel like leaving the physical body. Some consider progressive muscle relaxation as an active form of sensory deprivation.

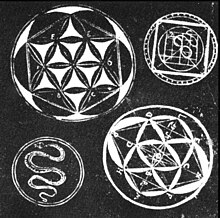

- Deep trance, meditation and visualization. The types of visualizations vary; some common analogies include climbing a rope to "pull out" of one's body, floating out of one's body, getting shot out of a cannon, and other similar approaches. This technique is considered hard to use for people who cannot properly relax. One example of such a technique is the popular Golden Dawn "Body of Light" Technique.

Mechanical induction

- Brainwave synchronization via audio/visual stimulation. Binaural beats can be used to induce specific brainwave frequencies, notably those predominant in various mind awake/body asleep states. Binaural induction of a "body asleep" 4 Hertz brainwave frequency was observed as effective by the Monroe Institute, and some authors consider binaural beats to be significantly supportive of OBE initiation when used in conjunction with other techniques. Simultaneous introduction of "mind awake" beta frequencies (detectable in the brains of normal, relaxed awakened individuals) was also observed as constructive. Another popular technology uses sinusoidal wave pulses to achieve similar results, and the drumming accompanying Native American religious ceremonies is also believed to have heightened receptivity to "other worlds" through brainwave entrainment mechanisms.

- Direct stimulation of the vestibular cortex.

- Electrical stimulation of the brain, particularly the temporoparietal junction (see Blanke study below).

- Sensory deprivation. This approach aims to induce intense disorientation by removal of space and time references. Flotation tanks or pink noise played through headphones are often employed for this purpose.

- Sensory overload, the opposite of sensory deprivation. The subject can for instance be rocked for a long time in a specially designed cradle, or submitted to light forms of torture, to cause the brain to shut itself off from all sensory input. Both conditions tend to cause confusion and this disorientation often permits the subject to experience vivid, ethereal out-of-body experiences.

- Strong g-forces that causes blood to drain from parts of the brain, as experienced for example in high-performance aircraft or high-G training for pilots and astronauts.

- An apparatus that uses a head-mounted display and a touch that confuses the sense of proprioception (and which can also create the sensation of additional limbs).

OBE theories

Psychological

In the fields of cognitive science and psychology OBEs are considered dissociative experiences arising from different psychological and neurological factors. Scientists consider the OBE to be an experience from a mental state, like a dream or an altered state of consciousness without recourse to the paranormal.

Charles Richet (1887) held that OBEs are created by the subject's memory and imagination processes and are no different from dreams. James H. Hyslop (1912) wrote that OBEs occur when the activity of the subconscious mind dramatizes certain images to give the impression the subject is in a different physical location. Eugéne Osty (1930) considered OBEs to be nothing more than the product of imagination. Other early researchers (such as Schmeing, 1938) supported psychophysiological theories. G. N. M. Tyrrell interpreted OBEs as hallucinatory constructs relating to subconscious levels of personality.

Donovan Rawcliffe (1959) connected the OBE experience with psychosis and hysteria. Other researchers have discussed the phenomena of the OBE in terms of a distortion of the body image (Horowitz, 1970) and depersonalization (Whitlock, 1978). The psychologists Nandor Fodor (1959) and Jan Ehrenwald (1974) proposed that an OBE is a defense mechanism designed to deal with the threat of death. According to (Irin and Watt, 2007) Jan Ehrenwald had described the out-of-body experience (OBE) "as an imaginal confirmation of the quest for immortality, a delusory attempt to assure ourselves that we possess a soul that exists independently of the physical body". The psychologists Donald Hebb (1960) and Cyril Burt (1968) wrote on the psychological interpretation of the OBE involving body image and visual imagery. Graham Reed (1974) suggested that the OBE is a stress reaction to a painful situation, such as the loss of love. John Palmer (1978) wrote that the OBE is a response to a body image change causing a threat to personal identity.

Carl Sagan (1977) and Barbara Honegger (1983) wrote that the OBE experience may be based on a rebirth fantasy or reliving of the birth process based on reports of tunnel-like passageways and a cord-like connection by some OBErs which they compared to an umbilical cord. Susan Blackmore (1978) came to the conclusion that the OBE is a hallucinatory fantasy as it has the characteristics of imaginary perceptions, perceptual distortions and fantasy-like perceptions of the self (such as having no body). Ronald Siegel (1980) also wrote that OBEs are hallucinatory fantasies.

Harvey Irwin (1985) presented a theory of the OBE involving attentional cognitive processes and somatic sensory activity. His theory involved a cognitive personality construct known as psychological absorption and gave instances of the classification of an OBE as examples of autoscopy, depersonalization and mental dissociation. The psychophysiologist Stephen Laberge (1985) has written that the explanation for OBEs can be found in lucid dreaming. David Hufford (1989) linked the OBE experience with a phenomenon he described as a nightmare waking experience, a type of sleep paralysis. Other scientists have also linked OBEs to cases of hypnagogia and sleep paralysis (cataplexy).

In case studies fantasy proneness has been shown to be higher among OBErs than those who have not had an OBE. The data has shown a link between the OBE experience in some cases to fantasy prone personality (FPP). In a case study involving 167 participants the findings revealed that those who claimed to have experienced the OBE were "more fantasy prone, higher in their belief in the paranormal and displayed greater somatoform dissociation." Research from studies has also suggested that OBEs are related to cognitive-perceptual schizotypy.

Terence Hines (2003) has written that spontaneous out-of-body experiences can be generated by artificial stimulation of the brain and this strongly suggests that the OBE experience is caused from "temporary, minor brain malfunctions, not by the person's spirit (or whatever) actually leaving the body." In a study review of neurological and neurocognitive data (Bünning and Blanke, 2005) wrote that OBEs are due to "functional disintegration of lower-level multisensory processing and abnormal higher-level self-processing at the temporoparietal junction." Some scientists suspect that OBEs are the result of a mismatch between visual and tactile signals.

Richard Wiseman (2011) has noted that OBE research has focused on finding a psychological explanation and "out-of-body experiences are not paranormal and do not provide evidence for the soul. Instead, they reveal something far more remarkable about the everyday workings of your brain and body." A study conducted by Jason Braithwaite and colleagues (2011) linked the OBE to "neural instabilities in the brain's temporal lobes and to errors in the body's sense of itself". Braithwaite et al. (2013) reported that the "current and dominant view is that the OBE occurs due to a temporary disruption in multi-sensory integration processes."

Paranormal

Writers in the fields of parapsychology and occultism have written that OBEs are not psychological and that a soul, spirit or subtle body can detach itself out of the body and visit distant locations. Out-of-the-body experiences were known during the Victorian period in spiritualist literature as "travelling clairvoyance". In old Indian scriptures, such a state of consciousness is also referred to as Turiya, which can be achieved by deep yogic and meditative activities, during which yogis may be liberated from the duality of mind and body, allowing them to intentionally leave the body and then return to it. The body carrying out this journey is called "Vigyan dehi" ("Scientific body"). The psychical researcher Frederic Myers referred to the OBE as a "psychical excursion". An early study that described alleged cases of OBE was the two-volume Phantasms of the Living, published in 1886 by the psychical researchers Edmund Gurney, Myers, and Frank Podmore. The book was largely criticized by the scientific community because the anecdotal reports in almost every case lacked evidential substantiation.

The theosophist Arthur Powell (1927) was an early author to advocate the subtle body theory of OBEs. Sylvan Muldoon (1936) embraced the concept of an etheric body to explain the OBE experience. The psychical researcher Ernesto Bozzano (1938) had also supported a similar view describing the phenomena of the OBE experience in terms of bilocation in which an "etheric body" can release itself from the physical body in rare circumstances. The subtle body theory was also supported by occult writers such as Ralph Shirley (1938), Benjamin Walker (1977), and Douglas Baker (1979). James Baker (1954) wrote that a mental body enters an "intercosmic region" during the OBE. Robert Crookall supported the subtle body theory of OBEs in several publications.

The paranormal interpretation of OBEs has not been supported by all researchers within the study of parapsychology. Gardner Murphy (1961) wrote that OBEs are "not very far from the known terrain of general psychology, which we are beginning to understand more and more without recourse to the paranormal".

In the 1970s, Karlis Osis conducted many OBE experiments with the psychic Alex Tanous. In one series of these experiments, he was asked whilst in an OBE state whether he could identify coloured targets that were placed in remote locations. Osis reported that there were 114 hits in 197 trials. However, the controls for the experiments have been criticized and, according to Susan Blackmore, the final result was not particularly significant since 108 hits would have been expected by chance alone. Blackmore noted that the results provide "no evidence for accurate perception in the OBE".

In April 1977, a patient from Harborview Medical Center known as Maria claimed to have experienced an out-of-body experience. During her OBE she claimed to have floated outside her body and outside the hospital. Maria later told her social worker Kimberly Clark that during the OBE she had observed a tennis shoe on the third floor window ledge to the north side of the building. Clark then went to the north wing of the building and by looking out of the window could see a tennis shoe on one of the ledges. Clark published the account in 1984. The story has since been used in many paranormal books as evidence that a spirit can leave the body.

In 1996, Hayden Ebbern, Sean Mulligan and Barry Beyerstein visited the Medical Center to investigate Clark's story. They placed a tennis shoe on the same ledge and found that it was visible from within the building and could easily have been observed by a patient lying in bed. They also discovered that the tennis shoe was easy to observe from outside the building and suggested that Maria may have overheard a comment about it during her three days in the hospital and then incorporated it into her OBE. They concluded "Maria's story merely reveals the naiveté and the power of wishful thinking" from OBE researchers seeking a paranormal explanation. Clark did not publish the description of the case until seven years after it happened, casting doubt on the story. Richard Wiseman has said that although the story is not evidence for anything paranormal it has been "endlessly repeated by writers who either couldn't be bothered to check the facts, or were unwilling to present their readers with the more skeptical side of the story." Clark responded to the accusations made in a separate paper.

Astral projection

Astral projection is a paranormal interpretation of out-of-body experiences that assumes the existence of one or more non-physical planes of existence and an associated body beyond the physical. Commonly such planes are called astral, etheric, or spiritual. Astral projection is often experienced as the spirit or astral body leaving the physical body to travel in the spirit world or astral plane.

OBE studies

Early collections of OBE cases had been made by Ernesto Bozzano (Italy) and Robert Crookall (UK). Crookall approached the subject from a spiritualistic position, and collected his cases predominantly from spiritualist newspapers such as the Psychic News, which appears to have biased his results in various ways. For example, the majority of his subjects reported seeing a cord connecting the physical body and its observing counterpart; whereas Green (see below) found that less than 4% of her subjects noticed anything of this sort, and some 80% reported feeling they were a "disembodied consciousness", with no external body at all.

The first extensive scientific study of OBEs was made by Celia Green (1968). She collected written, first-hand accounts from a total of 400 subjects, recruited by means of appeals in the mainstream media, and followed up by questionnaires. Her purpose was to provide a taxonomy of the different types of OBE, viewed simply as an anomalous perceptual experience or hallucination, while leaving open the question of whether some of the cases might incorporate information derived by extrasensory perception.

International Academy of Consciousness - Global Survey

In 1999, at the 1st International Forum of Consciousness Research in Barcelona, research-practitioners Wagner Alegretti and Nanci Trivellato presented preliminary findings of an online survey on the out-of-body experience answered by internet users interested in the subject; therefore, not a sample representative of the general population.

1,007 (85%) of the first 1,185 respondents reported having had an OBE. 37% claimed to have had between two and ten OBEs. 5.5% claimed more than 100 such experiences. 45% of those who reported an OBE said they successfully induced at least one OBE by using a specific technique. 62% of participants claiming to have had an OBE also reported having enjoyed nonphysical flight; 40% reported experiencing the phenomenon of self-bilocation (i.e. seeing one's own physical body whilst outside the body); and 38% claimed having experienced self-permeability (passing through physical objects such as walls). The most commonly reported sensations experienced in connection with the OBE were falling, floating, repercussions e.g. myoclonia (the jerking of limbs, jerking awake), sinking, torpidity (numbness), intracranial sounds, tingling, clairvoyance, oscillation and serenity.

Another reported common sensation related to OBE was temporary or projective catalepsy, a more common feature of sleep paralysis. The sleep paralysis and OBE correlation was later corroborated by the Out-of-Body Experience and Arousal study published in Neurology by Kevin Nelson and his colleagues from the University of Kentucky in 2007. The study discovered that people who have out-of-body experiences are more likely to experience sleep paralysis.

Also noteworthy, is the Waterloo Unusual Sleep Experiences Questionnaire that further illustrates the correlation.

Miss Z study

In 1968, Charles Tart conducted an OBE experiment with a subject known as Miss Z for four nights in his sleep laboratory. The subject was attached to an EEG machine and a five-digit code was placed on a shelf above her bed. She did not claim to see the number on the first three nights but on the fourth gave the number correctly. The psychologist James Alcock criticized the experiment for inadequate controls and questioned why the subject was not visually monitored by a video camera. Martin Gardner has written the experiment was not evidence for an OBE and suggested that whilst Tart was "snoring behind the window, Miss Z simply stood up in bed, without detaching the electrodes, and peeked." Susan Blackmore wrote "If Miss Z had tried to climb up, the brain-wave record would have showed a pattern of interference. And that was exactly what it did show."

Neurology and OBE-like experiences

There are several possible physiological explanations for parts of the OBE. OBE-like experiences have been induced by stimulation of the brain. OBE-like experience has also been induced through stimulation of the posterior part of the right superior temporal gyrus in a patient. Positron-emission tomography was also used in this study to identify brain regions affected by this stimulation. The term OBE-like is used above because the experiences described in these experiments either lacked some of the clarity or details of normal OBEs, or were described by subjects who had never experienced an OBE before. Such subjects were therefore not qualified to make claims about the authenticity of the experimentally-induced OBE.

British psychologist Susan Blackmore and others suggest that an OBE begins when a person loses contact with sensory input from the body while remaining conscious. The person retains the illusion of having a body, but that perception is no longer derived from the senses. The perceived world may resemble the world he or she generally inhabits while awake, but this perception does not come from the senses either. The vivid body and world is made by our brain's ability to create fully convincing realms, even in the absence of sensory information. This process is witnessed by each of us every night in our dreams, though OBEs are claimed to be far more vivid than even a lucid dream.

Irwin pointed out that OBEs appear to occur under conditions of either very high or very low arousal. For example, Green found that three quarters of a group of 176 subjects reporting a single OBE were lying down at the time of the experience, and of these 12% considered they had been asleep when it started. By contrast, a substantial minority of her cases occurred under conditions of maximum arousal, such as a rock-climbing fall, a traffic accident, or childbirth. McCreery has suggested that this paradox may be explained by reference to the fact that sleep can supervene as a reaction to extreme stress or hyper-arousal. He proposes that OBEs under both conditions, relaxation and hyper-arousal, represent a form of "waking dream", or the intrusion of Stage 1 sleep processes into waking consciousness.

Olaf Blanke studies

Research by Olaf Blanke in Switzerland found that it is possible to reliably elicit experiences somewhat similar to the OBE by stimulating regions of the brain called the right temporoparietal junction (TPJ; a region where the temporal lobe and the parietal lobe of the brain come together). Blanke and his collaborators in Switzerland have explored the neural basis of OBEs by showing that they are reliably associated with lesions in the right TPJ region and that they can be reliably elicited with electrical stimulation of this region in a patient with epilepsy. These elicited experiences may include perceptions of transformations of the patient's arms and legs (complex somatosensory responses) and whole-body displacements (vestibular responses).

In neurologically normal subjects, Blanke and colleagues then showed that the conscious experience of the self and body being in the same location depends on multisensory integration in the TPJ. Using event-related potentials, Blanke and colleagues showed the selective activation of the TPJ 330–400 ms after stimulus onset when healthy volunteers imagined themselves in the position and visual perspective that generally are reported by people experiencing spontaneous OBEs. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the same subjects impaired mental transformation of the participant's own body. No such effects were found with stimulation of another site or for imagined spatial transformations of external objects, suggesting the selective implication of the TPJ in mental imagery of one's own body.

In a follow up study, Arzy et al. showed that the location and timing of brain activation depended on whether mental imagery is performed with mentally embodied or disembodied self location. When subjects performed mental imagery with an embodied location, there was increased activation of a region called the "extrastriate body area" (EBA), but when subjects performed mental imagery with a disembodied location, as reported in OBEs, there was increased activation in the region of the TPJ. This leads Arzy et al. to argue that "these data show that distributed brain activity at the EBA and TPJ as well as their timing are crucial for the coding of the self as embodied and as spatially situated within the human body."

Blanke and colleagues thus propose that the right temporal-parietal junction is important for the sense of spatial location of the self, and that when these normal processes go awry, an OBE arises.

In August 2007 Blanke's lab published research in Science demonstrating that conflicting visual-somatosensory input in virtual reality could disrupt the spatial unity between the self and the body. During multisensory conflict, participants felt as if a virtual body seen in front of them was their own body and mislocalized themselves toward the virtual body, to a position outside their bodily borders. This indicates that spatial unity and bodily self-consciousness can be studied experimentally and is based on multisensory and cognitive processing of bodily information.

Ehrsson study

In August 2007, Henrik Ehrsson, then at the Institute of Neurology at University College of London (now at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden), published research in Science demonstrating the first experimental method that, according to the scientist's claims in the publication, induced an out-of-body experience in healthy participants. The experiment was conducted in the following way:

The study participant sits in a chair wearing a pair of head-mounted video displays. These have two small screens over each eye, which show a live film recorded by two video cameras placed beside each other two metres behind the participant's head. The image from the left video camera is presented on the left-eye display and the image from the right camera on the right-eye display. The participant sees these as one "stereoscopic" (3D) image, so they see their own back displayed from the perspective of someone sitting behind them.

The researcher then stands just beside the participant (in their view) and uses two plastic rods to simultaneously touch the participant's actual chest out-of-view and the chest of the illusory body, moving this second rod towards where the illusory chest would be located, just below the camera's view.

The participants confirmed that they had experienced sitting behind their physical body and looking at it from that location.

Both critics and the experimenter himself note that the study fell short of replicating "full-blown" OBEs. As with previous experiments which induced sensations of floating outside of the body, Ehrsson's work does not explain how a brain malfunction might cause an OBE. Essentially, Ehrsson created an illusion that fits a definition of an OBE in which "a person who is awake sees his or her body from a location outside the physical body."

Awareness during Resuscitation Study

In 2001, Sam Parnia and colleagues investigated out of body claims by placing figures on suspended boards facing the ceiling, not visible from the floor. Parnia wrote "anybody who claimed to have left their body and be near the ceiling during resuscitation attempts would be expected to identify those targets. If, however, such perceptions are psychological, then one would obviously not expect the targets to be identified." The philosopher Keith Augustine, who examined Parnia's study, has written that all target identification experiments have produced negative results. Psychologist Chris French wrote regarding the study "unfortunately, and somewhat atypically, none of the survivors in this sample experienced an OBE."

In the autumn of 2008, 25 UK and US hospitals began participation in a study, coordinated by Sam Parnia and Southampton University known as the AWARE study (AWAreness during REsuscitation). Following on from the work of Pim van Lommel in the Netherlands, the study aims to examine near-death experiences in 1,500 cardiac arrest survivors and so determine whether people without a heartbeat or brain activity can have documentable out-of-body experiences. As part of the study Parnia and colleagues have investigated out of body claims by using hidden targets placed on shelves that could only be seen from above. Parnia has written "if no one sees the pictures, it shows these experiences are illusions or false memories".

In 2014 Parnia issued a statement indicating that the first phase of the project has been completed and the results are undergoing peer review for publication in a medical journal. No subjects saw the images mounted out of sight according to Parnia's early report of the results of the study at an American Heart Association meeting in November 2013. Only two out of the 152 patients reported any visual experiences, and one of them described events that could be verified (as the other one's condition worsened before the detailed interview). The two NDEs occurred in an area where "no visual targets had been placed".

On October 6, 2014, the results of the study were published in the journal Resuscitation. Less than 20% of cardiac arrest patients were able to be interviewed, as most of them died or were too sick even after successful resuscitation. Among those who reported a perception of awareness and completed further interviews, 46% experienced a broad range of mental recollections in relation to death that were not compatible with the commonly used term of NDEs. These included fearful and persecutory experiences. Only 9% had experiences compatible with NDEs and 2% exhibited full awareness compatible with OBEs with explicit recall of 'seeing' and 'hearing' events. One case was validated and timed using auditory stimuli during cardiac arrest. According to Caroline Watt "The one 'verifiable period of conscious awareness' that Parnia was able to report did not relate to this objective test. Rather, it was a patient giving a supposedly accurate report of events during his resuscitation. He didn't identify the pictures, he described the defibrillator machine noise. But that's not very impressive since many people know what goes on in an emergency room setting from seeing recreations on television." However, it was impossible for him to describe any hidden targets, as there were none in the room where his OBE occurred, and the rest of his description was also very precise, including the description and later correct identification of a doctor who took part in his resuscitation.

AWARE Study II

As of May 2016, a posting at the UK Clinical Trials Gateway website describes plans for AWARE II, a two-year multicenter observational study of 900-1500 patients experiencing cardiac arrest, with subjects being recruited starting on 1 August 2014 and that the scheduled end date was 31 May 2017. The study was extended, continuing until 2020.

Smith & Messier

In 2014, a functional imaging study reported the case of a woman who could experience out of body experience at will. She reported developing the ability as a child and associated it with difficulties in falling sleep. Her OBEs continued into adulthood but became less frequent. She was able to see herself rotating in the air above her body, lying flat, and rolling in the horizontal plane. She reported sometimes watching herself move from above but remained aware of her unmoving "real" body. The participant reported no particular emotions linked to the experience. "[T]he brain functional changes associated with the reported extra-corporeal experience (ECE) were different than those observed in motor imagery. Activations were mainly left-sided and involved the left supplementary motor area and supramarginal and posterior superior temporal gyri, the last two overlapping with the temporal parietal junction that has been associated with out-of-body experiences. The cerebellum also showed activation that is consistent with the participant's report of the impression of movement during the ECE. There was also left middle and superior orbital frontal gyri activity, regions often associated with action monitoring."

OBE training and research facilities

The Monroe Institute's Nancy Penn Center is a facility specializing in out-of-body experience induction. The Center for Higher Studies of the Consciousness in Brazil is another large OBE training facility. Olaf Blanke's Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience has become a well-known laboratory for OBE research.