| Major depressive episode | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

A major depressive episode (MDE) is a period characterized by the symptoms of major depressive disorder. Those affected primarily have a depressed mood for at least two weeks or more and a loss of interest or pleasure in everyday activities. Other symptoms can include feelings of emptiness, hopelessness, anxiety, worthlessness, guilt, irritability, changes in appetite, problems concentrating, remembering details, making decisions, and thoughts of suicide. Insomnia or hypersomnia, aches, pains, or digestive problems that are resistant to treatment may also be present.

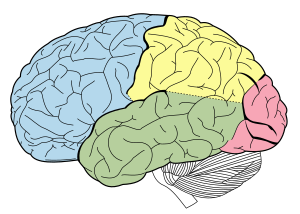

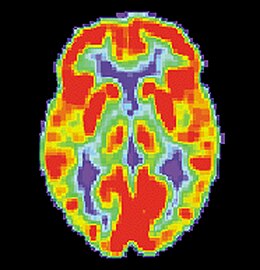

Although the exact origin of depression is still not clear, it is believed to involve biological, psychological, and social aspects. Factors like socioeconomic status, life experience, genetics, and personality tendencies play a role in the development of depression and may represent an increased risk of developing a major depressive episode. There are many theories as to how depression occurs. One interpretation is that neurotransmitters in the brain are out of balance, resulting in feelings of worthlessness and despair. Magnetic resonance imaging shows that the brains of people who have depression look different than the brains of people who do not exhibit signs of depression. A family history of depression increases the chance of being diagnosed.

Emotional pain and economic costs are associated with depression in many cases. In the United States and Canada, the costs associated with major depression are comparable to those related to heart disease, diabetes, and back problems and are greater than the costs of hypertension. According to the Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, there is a direct correlation between a major depressive episode and unemployment.

Treatments for a major depressive episode include psychotherapy and antidepressants, although in more serious cases, hospitalization or intensive outpatient treatment may be required.

Signs and symptoms

The criteria below are based on the formal DSM-5 criteria for a major depressive episode. A diagnosis of a major depressive episode requires the patient to have experienced five or more of the symptoms below, one of which must be either a depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure (although both are frequently present). These symptoms must be present for at least 2 weeks and represent a change from the patient's normal behavior.

Depressed mood and loss of interest (anhedonia)

Either a depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure must be presented for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode. Depressed mood is the most common symptom seen in major depressive episodes. Interest in or pleasure in everyday activities can be decreased; this is referred to as anhedonia. These feelings must be present on an everyday basis for two weeks or longer to meet the DSM-V criteria for a major depressive episode. In addition, the person may experience one or more of the following emotions: sadness, emptiness, hopelessness, indifference, anxiety, tearfulness, pessimism, emotional numbness, or irritability. In children and adolescents, a depressed mood often appears more irritable. There may be a loss of interest in or desire for sex or other activities once found to be pleasant. Friends and family of the depressed person may notice that they have withdrawn from friends, neglected them, or quit doing activities that were once a source of enjoyment.

Sleep

Major depressive episodes are known to cause sleep disturbances such as hypersomnia, which causes excessive sleep patterns, or sleep deprivation, like insomnia. Insomnia is the most common type of sleep disturbance for people who are clinically depressed. Symptoms of insomnia include trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, or waking up too early in the morning. The most common symptom of insomnia is waking up in the middle of the night and having trouble falling back asleep. Hypersomnia is a less common type of sleep disturbance. It may include sleeping for prolonged periods at night and into the morning or increased sleeping during the daytime. The sleep may not be restful, and the person may feel sluggish despite many hours of sleep, which may amplify their depressive symptoms and interfere with other aspects of their lives. This type of sleep disorder may make it harder for a person to fall and stay asleep at night compared to during the day. Hypersomnia is often associated with atypical depression as well as seasonal affective disorder.

Feelings of guilt or worthlessness

Depressed people may have feelings of guilt that go beyond a normal level or be delusional. These feelings of guilt and/or worthlessness are excessive and imagined. Major depressive episodes are notable for a significant, often inexplicable, drop in self-esteem. The guilt and worthlessness experienced in a major depressive episode can range from subtle feelings of guilt to frank delusions, shame, and humiliation. Additionally, self-loathing is common in clinical depression and can lead to a downward spiral when combined with other symptoms. A lot of people with depression have distorted thought patterns, and genuinely believe that they're not good for anything or anyone. They tend to have severe self-esteem issues, and don't recognize their value as a human being. They also begin to feel as though their lives have no meaning or purpose.

Loss of energy

Individuals going through a major depressive episode often have a general lack of energy, as well as fatigue and tiredness, nearly every day for at least 2 weeks. A person may feel tired without having engaged in any physical activity, and day-to-day tasks become increasingly difficult. It becomes very difficult for someone with depression to get things done during the day. Even small tasks, like showering, become exhausting, causing a lot of people with depression to stop taking care of themselves entirely.

Decreased concentration

Nearly every day, the person may be indecisive or have trouble thinking or concentrating. These issues cause significant difficulty in functioning for those involved in intellectually demanding activities, such as school and work, especially in difficult fields. Depressed people often describe a slowing of thought, an inability to concentrate and make decisions, and being easily distracted. In the elderly, the decreased concentration caused by a major depressive episode may present as deficits in memory. This is referred to as pseudodementia and often goes away with treatment. Decreased concentration may be reported by the patient or observed by others. Since depression makes it more difficult to stay concentrated, a lot of people will notice that they aren't doing well in school or at their job, which makes their depression even worse.

Change in eating, appetite, or weight

In a major depressive episode, appetite is most often decreased, although a small percentage of people experience an increase in appetite. A person experiencing a depressive episode may have a marked loss or gain of weight (5% of their body weight in one month). A decrease in appetite may result in unintentional weight loss when a person is not dieting. Feelings of low self-worth make them not want to eat anymore. Some people experience an increase in appetite and may gain significant amounts of weight. They may crave certain types of food, such as sweets or carbohydrates. In this instance, low self-worth can lead to self-soothing through eating. In children, failure to make expected weight gains may be counted towards this criteria. Overeating is often associated with atypical depression. When people have depression, they usually stop taking care of their bodies and "wither away." A lack of healthy eating habits is a tell-tale sign of classic depression.

Motor activity

Nearly every day, others may see that the person's activity level is not normal. They might notice that the person takes longer to complete simple tasks or that they are doing a lot at once. People with depression may be overly active (psychomotor agitation) or very lethargic (psychomotor retardation). Psychomotor agitation is marked by an increase in body activity, which may result in restlessness, an inability to sit still, pacing, hand wringing, or fidgeting with clothes or objects. This could also be linked to anxiety, since depression and anxiety are often seen together. Psychomotor retardation results in a decrease in body activity or thinking. In this case, a depressed person may demonstrate a slowing of thinking, speaking, or body movement. They may speak more softly or say less than usual. This is because they do not have the energy to expend as a normal person would. To meet diagnostic criteria, changes in motor activity must be so abnormal that it can be observed by others. Personal reports of feeling restless or slow do not count towards the diagnostic criteria.

Thoughts of death and suicide

A person going through a major depressive episode may have repeated thoughts about death (other than the fear of dying) or suicide (with or without a plan), or may have made a suicide attempt. Suicidal ideation can be common amongst victims of depression, which is when a person often thinks about not being alive anymore but does not yet have a plan to carry it out. The frequency and intensity of thoughts about suicide can range from believing that friends and family would be better off if one were dead to frequent thoughts about committing suicide (generally related to wishing to stop the emotional pain) to detailed plans about how the suicide would be carried out. Those who are more severely suicidal may have made specific plans and decided upon a day and location for the suicide attempt. When this happens, they often keep to themselves about it and may do it when and where they think no one would suspect.

Comorbid disorders

Major depressive episodes may show comorbidity (association) with other physical and mental health problems. About 20–25% of individuals with a chronic general medical condition will develop major depression. Common comorbid disorders include eating disorders, substance-related disorders, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Up to 25% of people who experience a major depressive episode have a pre-existing dysthymic disorder.

Some people who have a fatal illness or are at the end of their lives may experience depression, although this is not universal.

Causes

The cause of a major depressive episode is not well understood. Despite its longstanding prominence in pharmaceutical advertising, the myth that low serotonin levels cause depression is not supported by scientific evidence. There are usually many factors that play into a person's depression. The mechanism is believed to be a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors. A major depressive episode can often follow an acute stress in someone's life, such as the death of a loved one, or being fired from a job. Evidence suggests that psychosocial stressors play a larger role in the first 1–2 depressive episodes, while having less influence in later episodes. People who experience a major depressive episode often have other mental health issues.

Other risk factors for a depressive episode include:

- Early childhood trauma

- Family history of a mood disorder

- Lack of interpersonal relationships

- Personality (insecure, worried, stress-sensitive, obsessive, unassertive, dependent)

- Postpartum

- Recent negative life events

Studies show that depression can be passed down in families, but this is believed to be due to a combined effect of genetic, and environmental factors. Other medical conditions, like hypothyroidism, for example, may cause people to experience similar symptoms as a major depressive episode, however this would be considered a mood disorder due to a general medical condition, according to the DSM-V. For some people, depression runs in their family so it's likely that the depression will be passed down to them. For other people, depression might be completely environmental. It could also be a mix of both.

Diagnosis

Criteria

The two main symptoms of a major depressive episode are a depressed mood and a loss of interest or pleasure. From the list below, one bold symptom and four other symptoms must be presented for at least 2 weeks for a diagnosis of a major depressive episode. These symptoms must be causing significant distress or impairment in functioning.

- Change in appetite

- Change in body activity (psychomotor changes)

- Change in sleep

- Depressed mood

- Feelings of worthlessness and excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Indecisiveness, confusion, or a decrease in concentration

- Loss of energy

- Loss of interest or pleasure

- Suicidal ideation

To diagnose a major depressive episode, a trained healthcare provider must make sure that:

- The symptoms are not due to any direct physiological effect of a substance (e.g., abuse of a drug or medication) or a general medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism).

- The symptoms do not meet the criteria for a mixed episode.

- The symptoms must cause considerable distress or impair functioning at work, in social settings, or in other important areas to qualify as an episode.

Workup

No labs are diagnostic of a depressive episode. But some labs can help rule out general medical conditions that may mimic the symptoms of a depressive episode. Healthcare providers may order some routine blood work, including routine blood chemistry, CBC with differential, thyroid function studies, and Vitamin B12 levels, before making a diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

There are other mental health disorders or medical conditions to consider before diagnosing a major depressive episode: A doctor or psychiatrist should consider these options before making a definitive diagnosis, in order to avoid misdiagnosing a patient.

- Adjustment disorder

- Anxiety disorder (Generalized anxiety, PTSD, obsessive-compulsive disorder)

- Bipolar disorder

- Cyclothymic disorder

- Depression due to a general medical condition

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

- Gender dysphoria

- Persistent depressive disorder

- Personality disorder with depressive symptoms

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- Substance abuse or Substance use disorder

Screening

Healthcare providers may screen patients in the general population for depression using a screening tool, such as the Patient Healthcare Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2). If the PHQ-2 screening is positive for depression, a provider may then administer the PHQ-9. The Geriatric Depression Scale is a screening tool that can be used in the elderly population.

Treatment

Depression is a treatable illness. Treatments for a major depressive episode may be provided by mental health specialists (i.e. psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, counselors, etc.), mental health centers or organizations, hospitals, outpatient clinics, social service agencies, private clinics, peer support groups, clergy, and employee assistance programs. The treatment plan could include psychotherapy alone, antidepressant medications alone, or a combination of medication and psychotherapy.

For major depressive episodes of severe intensity (multiple symptoms, minimal mood reactivity, severe functional impairment), combined psychotherapy, and antidepressant medications are more effective than psychotherapy alone. Meta-analyses suggest that the combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant medications is more effective in treating mild and moderate forms of depression as well, compared to either type of treatment alone. Patients with severe symptoms may require outpatient treatment or hospitalization.

The treatment of a major depressive episode can be split into 3 phases:

- Acute phase: the goal of this phase is to resolve the current major depressive episode

- Continuation: this phase continues the same treatment from the acute phase for 4–8 months after the depressive episode has resolved and the goal is to prevent relapse

- Maintenance: this phase is not necessary for every patient but is often used for patients who have experienced 2–3 or more major depressive episodes. Treatment may be maintained indefinitely to prevent the occurrence and severity of future episodes.

Therapy

Psychotherapy, also known as talk therapy, counseling, or psychosocial therapy, is characterized by a patient talking about their condition and mental health issues with a trained therapist. Therapy alone has been proven to benefit people who are struggling with various mental illnesses. Different types of psychotherapy are used as a treatment for depression. These include cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness techniques. Evidence shows that cognitive behavioral therapy can be as effective as medication in the treatment of a major depressive episode.

Psychotherapy may be the first treatment used for mild to moderate depression, especially when psychosocial stressors are playing a large role. Psychotherapy alone may not be as effective for more severe forms of depression, such as depression where there's a chemical imbalance in the brain.

Some of the main forms of psychotherapies used for the treatment of a major depressive episode, along with what makes them unique are included below:

- Cognitive psychotherapy: focus on patterns of thinking

- Interpersonal psychotherapy: focus on relationships, losses, and conflict resolution

- Problem-solving psychotherapy: focus on situations and strategies for problem-solving

- Psychodynamic psychotherapy: focus on defense mechanisms and coping strategies

Medication

Medications used to treat depression include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and atypical antidepressants such as mirtazapine, which do not fit neatly into any of the other categories. Different antidepressants work better for different individuals, it simply comes down to the person and what they prefer. It is often necessary to try several before finding one that works best for a specific patient. Some people may find it necessary to combine medications, which could mean two antidepressants or an antipsychotic medication in addition to an antidepressant. If a person's close relative has responded well to a certain medication, that treatment will likely work well for him or her. For example, if the depression is familial and the person's mother is prescribed an SSRI, then the same SSRI will most likely benefit the person as well. Antidepressant medications are effective in the acute, continuation, and maintenance phases of treatment, as described above.

The treatment benefits of antidepressant medications are often not seen until 1–2 weeks into treatment, with maximum benefits being reached around 4–6 weeks. It is likely that the person will actually experience more negative side effects during the first week or two, and want to stop taking their medication. However, it is crucial that they push through until the 4–6-week mark to know for sure how they feel about it. Most healthcare providers will monitor patients more closely during the acute phase of treatment and continue to monitor them at longer intervals in the continuation and maintenance phases.

Sometimes, people stop taking antidepressant medications due to side effects, although side effects often become less severe over time. Suddenly stopping treatment or missing several doses may cause withdrawal-like symptoms. Some studies have shown that antidepressants may increase short-term suicidal thoughts or actions, especially in children, adolescents, and young adults. However, antidepressants are more likely to reduce a person's risk of suicide in the long run.

Below are listed the main classes of antidepressant medications, some of the most common drugs in each category, and their major side effects:

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (isocarboxazid, phenelzine, selegiline): major side effects include high blood pressure (emergency) if eaten with foods rich in tyramine (e.g. cheeses, some meats, and home-brewed beer), sedation, tremor, and orthostatic hypotension

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (citalopram, escitalopram, paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline): major side effects include nausea, diarrhea, and sexual dysfunction such as erectile dysfunction or anorgasmia

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine): major side effects include nausea, diarrhea, increased heart rate, increased blood pressure, and tremors

- Tricyclic antidepressants (amitryptiline, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, nortriptyline): major side effects include sedation, low blood pressure when moving from sitting to standing (orthostatic hypotension), tremor, and heart issues like conduction delays or arrhythmias

Alternative treatments

There are several treatment options that exist for people who have experienced several episodes of major depression or have not responded to several treatments.

Electroconvulsive therapy is a treatment in which a generalized seizure is induced by means of electrical current. The mechanism of action of the treatment is not clearly understood but has been shown to be most effective in the most severely depressed patients. For this reason, electroconvulsive therapy is preferred for the most severe forms of depression or depression that has not responded to other treatments, known as refractory depression.

Vagus nerve stimulation is another alternative treatment that has been proven to be effective in the treatment of depression, especially people that have been resistant to four or more treatments. Some of the unique benefits of vagus nerve stimulation include improved neurocognitive function and a sustained clinical response.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is also an alternative treatment for a major depressive episode. It is a non-invasive treatment that is easily tolerated and shows an antidepressant effect, especially in more typical depression and younger adults.

Prognosis

If left untreated, a typical major depressive episode may last for several months. About 20% of these episodes can last two years or more. About half of depressive episodes end spontaneously. However, even after the major depressive episode is over, 20% to 30% of patients have residual symptoms, which can be distressing and associated with disability. Fifty percent of people will have another major depressive episode after the first. However, the risk of relapse is decreased by taking antidepressant medications for more than 6 months.

Symptoms completely improve in six to eight weeks in sixty to seventy percent of patients. The combination of therapy and antidepressant medications has been shown to improve resolution of symptoms and outcomes of treatment.

Suicide is the 8th leading cause of death in the United States. The risk of suicide is increased during a major depressive episode. However, the risk is even more elevated during the first two phases of treatment. There are several factors associated with an increased risk of suicide, listed below:

- Alcohol or drug use or comorbid psychiatric disorder

- Detailed plan

- Family history of suicide or mental illness

- Greater than 45 years of age

- History of suicide attempt or self-injurious behaviors

- Inability to accept help

- Lack of social support

- Male

- Poor health

- Psychotic features (auditory or visual hallucinations, disorganization of speech, behavior, or thought)

- Recent severe loss

- Severe depression

Epidemiology

Estimation of the number of people with major depressive episodes and major depressive disorder (MDD) vary significantly. Overall, 13–20% of people will experience significant depressive symptoms at some point in their life. The overall prevalence of MDD is slightly lower ranging from 3.7 to 6.7% of people. In their lifetime, 20% to 25% of women, and 7% to 12% of men will have a major depressive episode. The peak period of development is between the ages of 25 and 44 years. Onset of major depressive episodes or MDD often occurs to people in their mid-20s, and less often to those over 65. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in the elderly is around 1–2%. Elderly persons in nursing homes may have increased rates, up to 15–25%. African-Americans have higher rates of depressive symptoms compared to other races. Prepubescent girls are affected at a slightly higher rate than prepubescent boys.

In a National Institute of Mental Health study, researchers found that more than 40% of people with post-traumatic stress disorder had depression four months after the traumatic event they experienced.

Women who have recently given birth may be at increased risk for having a major depressive episode. This is referred to as postpartum depression and is a different health condition than the baby blues, a low mood that resolves within 10 days after delivery.