| Conversion disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

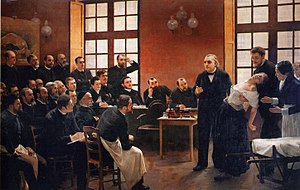

| Jean-Martin Charcot demonstrating hypnosis in a hysterical patient to his students. Hysteria as a clinical diagnosis was later replaced by conversion disorder. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, Neurology |

| Symptoms | Numbness, weakness, paralysis, seizures, tremor, fainting, impaired hearing, swallowing and vision |

| Causes | Long term stress |

| Treatment | Cognitive behavioral therapy, antidepressants, physical/occupational therapy |

Conversion disorder (CD), or functional neurologic symptom disorder, is a diagnostic category used in some psychiatric classification systems. It is sometimes applied to patients who present with neurological symptoms, such as numbness, blindness, paralysis, or fits, which are not consistent with a well-established organic cause, which cause significant distress, and can be traced back to a psychological trigger. It is thought that these symptoms arise in response to stressful situations affecting a patient's mental health or an ongoing mental health condition such as depression. Conversion disorder was retained in DSM-5, but given the subtitle functional neurological symptom disorder. The new criteria cover the same range of symptoms, but remove the requirements for a psychological stressor to be present and for feigning to be disproved. The ICD-10 classifies conversion disorder as a dissociative disorder, and the ICD-11 as a dissociative disorder with unspecified neurological symptoms.However, the DSM-IV classifies conversion disorder as a somatoform disorder.

Signs and symptoms

Conversion disorder begins with some stressor, trauma, or psychological distress. Usually the physical symptoms of the syndrome affect the senses or movement. Common symptoms include blindness, partial or total paralysis, inability to speak, deafness, numbness, difficulty swallowing, incontinence, balance problems, seizures, tremors, and difficulty walking. The symptom of feeling unable to breathe, but where the lips are not turning blue, can indicate conversion disorder or sleep paralysis. Sleep paralysis and narcolepsy can be ruled out with sleep tests. These symptoms are attributed to conversion disorder when a medical explanation for the conditions cannot be found. Symptoms of conversion disorder usually occur suddenly. Conversion disorder is typically seen in people aged 10 to 35, and affects between 0.011% and 0.5% of the general population.

Conversion disorder can present with motor or sensory symptoms including any of the following:

Motor symptoms or deficits:

- Impaired coordination or balance

- Weakness/paralysis of a limb or the entire body (hysterical paralysis or motor conversion disorders)

- Impairment or loss of speech (hysterical aphonia)

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or a sensation of a lump in the throat

- Urinary retention

- Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures or convulsions

- Persistent dystonia

- Tremor, myoclonus or other movement disorders

- Gait problems (astasia-abasia)

- Loss of consciousness (fainting)

Sensory symptoms or deficits:

- Impaired vision (hysterical blindness), double vision

- Impaired hearing (deafness)

- Loss or disturbance of touch or pain sensation

Conversion symptoms typically do not conform to known anatomical pathways and physiological mechanisms. It has sometimes been stated that the presenting symptoms tend to reflect the patient's own understanding of anatomy and that the less medical knowledge a person has, the more implausible are the presenting symptoms. However, no systematic studies have yet been performed to substantiate this statement.

Diagnosis

Definition

Conversion disorder is now contained under the umbrella term functional neurological symptom disorder. In cases of conversion disorder, there is a psychological stressor.

The diagnostic criteria for functional neurological symptom disorder, as set out in DSM-5, are:

- The patient has at least one symptom of altered voluntary motor or sensory function.

- Clinical findings provide evidence of incompatibility between the symptom and recognised neurological or medical conditions.

- The symptom or deficit is not better explained by another medical or mental disorder.

- The symptom or deficit causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning or warrants medical evaluation.

Specify type of symptom or deficit as:

- With weakness or paralysis

- With abnormal movement (e.g. tremor, dystonic movement, myoclonus, gait disorder)

- With swallowing symptoms

- With speech symptoms (e.g. dysphonia, slurred speech)

- With attacks or seizures

- With amnesia or memory loss

- With special sensory loss symptoms (e.g. visual blindness, olfactory loss, or hearing disturbance)

- With mixed symptoms.

Specify if:

- Acute episode: symptoms present for less than six months

- Persistent: symptoms present for six months or more.

Specify if:

- Psychological stressor (conversion disorder)

- No psychological stressor (functional neurological symptom disorder)

Exclusion of neurological disease

Conversion disorder presents with symptoms that typically resemble a neurological disorder such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, hypokalemic periodic paralysis or narcolepsy. The neurologist must carefully exclude neurological disease, through examination and appropriate investigations. However, it is not uncommon for patients with neurological disease to also have conversion disorder.

In excluding neurological disease, the neurologist has traditionally relied partly on the presence of positive signs of conversion disorder, i.e. certain aspects of the presentation that were thought to be rare in neurological disease but common in conversion. The validity of many of these signs has been questioned, however, by a study showing they also occur in neurological disease. One such symptom, for example, is la belle indifférence, described in DSM-IV as "a relative lack of concern about the nature or implications of the symptoms". In a later study, no evidence was found that patients with functional symptoms are any more likely to exhibit this than patients with a confirmed organic disease. In DSM-V, la belle indifférence was removed as a diagnostic criterion.

Another feature thought to be important was that symptoms tended to be more severe on the non-dominant (usually left) side of the body. There have been a number of theories about this, such as the relative involvement of cerebral hemispheres in emotional processing, or more simply, that it was "easier" to live with a functional deficit on the non-dominant side. However, a literature review of 121 studies established that this was not true, with publication bias the most likely explanation for this commonly held view. Although agitation is often assumed to be a positive sign of conversion disorder, release of epinephrine is a well-demonstrated cause of paralysis from hypokalemic periodic paralysis.

Misdiagnosis does sometimes occur. In a highly influential study from the 1960s, Eliot Slater demonstrated that misdiagnoses had occurred in one third of his 112 patients with conversion disorder. Later authors have argued that the paper was flawed, however, and a meta-analysis has shown that misdiagnosis rates since that paper was published are around four percent, the same as for other neurological diseases.

Deliberate feigning

Conversion disorder, by its nature, is more prone to deliberate feigning. One neuroimaging study suggested that feigning may be distinguished from conversion by the pattern of frontal lobe activation.

Psychological mechanism

The psychological mechanism of conversion can be the most difficult aspect of a conversion diagnosis. Even if there is a clear antecedent trauma or other possible psychological trigger, it is still not clear exactly how this gives rise to the symptoms observed. Patients with medically unexplained neurological symptoms may not have any psychological stressor, hence the use of the term "functional neurological symptom disorder" in DSM-5 as opposed to "conversion disorder", and DSM-5's removal of the need for a psychological trigger.

Treatment

There are a number of different treatments available to treat and manage conversion syndrome. Treatments for conversion syndrome include hypnosis, psychotherapy, physical therapy, stress management, and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Treatment plans will consider duration and presentation of symptoms and may include one or multiple of the above treatments. This may include the following:

- Occupational therapy to maintain autonomy in activities of daily living;

- Physiotherapy where appropriate.

- Treatment of comorbid depression or anxiety if present.

- Educating patients on the causes of their symptoms might help them learn to manage both the psychiatric and physical aspects of their condition. Psychological counseling is often warranted given the known relationship between conversion disorder and emotional trauma. This approach ideally takes place alongside other types of treatment.

There is little evidence-based treatment of conversion disorder. Other treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy, hypnosis, EMDR, and psychodynamic psychotherapy, EEG brain biofeedback need further trials. Psychoanalytic treatment may possibly be helpful. However, most studies assessing the efficacy of these treatments are of poor quality and larger, better controlled studies are urgently needed. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is the most common treatment, however boasts a mere 13% improvement rate.

Prognosis

Empirical studies have found that the prognosis for conversion disorder varies widely, with some cases resolving in weeks, and others enduring for years or decades. There is also evidence that there is no cure for conversion disorder, and that although patients may go into remission they can relapse at any point. Furthermore, many patients can get rid of their symptoms with time, treatments and reassurance.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Information on the frequency of conversion disorder in the West is limited, in part due to the complexities of the diagnostic process. In neurology clinics, the reported prevalence of unexplained symptoms among new patients is very high (between 30 and 60%). However, diagnosis of conversion typically requires an additional psychiatric evaluation, and since few patients will see a psychiatrist it is unclear what proportion of the unexplained symptoms are actually due to conversion. Large scale psychiatric registers in the US and Iceland found incidence rates of 22 and 11 newly diagnosed cases per 100,000 person-years, respectively. Some estimates claim that in the general population, between 0.011% and 0.5% of the population have conversion disorder.

Culture

Although it is often thought that the frequency of conversion may be higher outside of the West, perhaps in relation to cultural and medical attitudes, evidence of this is limited. A community survey of urban Turkey found a prevalence of 5.6%. Many authors have found occurrence of conversion to be more frequent in rural, lower socio-economic groups, where technological investigation of patients is limited and people may know less about medical and psychological concepts.

Gender

Historically, the concept of 'hysteria' was originally understood to be a condition exclusively affecting women, though the concept was eventually extended to men. In recent surveys of conversion disorder (formerly classified as "hysterical neurosis, conversion type"), females predominate, with between two and six female patients for every male but some research suggests this gender disparity may be confounded by higher rates of violence against women.

Age

Conversion disorder may present at any age but is rare in children younger than ten or in the elderly. Studies suggest a peak onset in the mid-to-late 30s.

History

The first evidence of functional neurological symptom disorder dates back to 1900 BC, when the symptoms were blamed on the uterus moving within the female body. The treatment varied "depending on the position of the uterus, which must be forced to return to its natural position. If the uterus had moved upwards, this could be done by placing malodorous and acrid substances near the woman's mouth and nostrils, while scented ones were placed near her vagina; on the contrary, if the uterus had lowered, the document recommends placing the acrid substances near her vagina and the perfumed ones near her mouth and nostrils."

In Greek mythology, hysteria, the original name for functional neurological symptom disorder, was thought to be caused by a lack of orgasms, uterine melancholy and not procreating. Plato, Aristotle and Hippocrates believed a lack of sex upsets the uterus. The Greeks believed it could be prevented and cured with wine and orgies. Hippocrates argued that a lack of regular sexual intercourse led to the uterus producing toxic fumes and caused it to move in the body, and that this meant all women should be married and enjoy a satisfactory sexual life.

From the 13th century, women with hysteria were exorcised, as it was believed that they were possessed by the devil. It was believed that if doctors could not find the cause of a disease or illness, it must be caused by the devil.

At the beginning of the 16th century, women were sexually stimulated by midwives in order to relieve their symptoms. Gerolamo Cardano and Giambattista della Porta believed polluted water and fumes caused the symptoms of hysteria. Towards the end of the century, however, the role of the uterus was no longer thought central to the disorder, with Thomas Willis discovering that the brain and central nervous system were the cause of the symptoms. Thomas Sydenham argued that the symptoms of hysteria may have an organic cause. He also proved the uterus is not the cause of symptom.

In 1692, in the US town of Salem, Massachusetts, there was an outbreak of hysteria. This led to the Salem witch trials, where the women accused of being witches had symptoms such as sudden movements, staring eyes and uncontrollable jumping.

During the 18th century, there was a move from the idea of hysteria being caused by the uterus to it being caused by the brain. This led to an understanding that it could affect both sexes. Jean-Martin Charcot argued that hysteria was caused by "a hereditary degeneration of the nervous system, namely a neurological disorder".

In the 19th century, hysteria moved from being considered a neurological disorder to being considered a psychological disorder, when Pierre Janet argued that "dissociation appears autonomously for neurotic reasons, and in such a way as to adversely disturb the individual's everyday life". However, as early as 1874, doctors including W. B. Carpenter and J. A. Omerod began to speak out against the hysteria phenomenon as there was no evidence to prove its existence.

Sigmund Freud referred to the condition as both hysteria and conversion disorder throughout his career. He believed those with the condition could not live in a mature relationship, and that those with the condition were unwell in order to achieve a "secondary gain", in that they are able to manipulate their situation to fit their needs or desires. He also found that both men and women could have the disorder.

Freud's model suggested the emotional charge deriving from painful experiences would be consciously repressed as a way of managing the pain, but that the emotional charge would be somehow "converted" into neurological symptoms. Freud later argued that the repressed experiences were of a sexual nature. As Peter Halligan comments, conversion has "the doubtful distinction among psychiatric diagnoses of still invoking Freudian mechanisms".

Pierre Janet, the other great theoretician of hysteria, argued that symptoms arose through the power of suggestion, acting on a personality vulnerable to dissociation. In this hypothetical process, the subject's experience of their leg, for example, is split off from the rest of their consciousness, resulting in paralysis or numbness in that leg.

Later authors have attempted to combine elements of these various models, but none of them has a firm empirical basis. In 1908, Steyerthal predicted that: "Within a few years the concept of hysteria will belong to history ... there is no such disease and there never has been. What Charcot called hysteria is a tissue woven of a thousand threads, a cohort of the most varied diseases, with nothing in common but the so-called stigmata, which in fact may accompany any disease." However, the term "hysteria" was still being used well into the 20th century.

Some support for the Freudian model comes from findings of high rates of childhood sexual abuse in conversion patients. Support for the dissociation model comes from studies showing heightened suggestibility in conversion patients. However, critics argue that it can be challenging to find organic pathologies for all symptoms, and so the practice of diagnosing patients with such symptoms as having hysteria led to the disorder being meaningless, vague and a sham diagnosis, as it does not refer to any definable disease. Furthermore, throughout its history, many patients have been misdiagnosed with hysteria or conversion disorder when they had organic disorders such as tumours or epilepsy or vascular diseases. This has led to patient deaths, a lack of appropriate care and suffering for the patients. Eliot Slater, after studying the condition in the 1950s, stated: "The diagnosis of 'hysteria' is all too often a way of avoiding a confrontation with our own ignorance. This is especially dangerous when there is an underlying organic pathology, not yet recognised. In this penumbra we find patients who know themselves to be ill but, coming up against the blank faces of doctors who refuse to believe in the reality of their illness, proceed by way of emotional lability, overstatement and demands for attention ... Here is an area where catastrophic errors can be made. In fact it is often possible to recognise the presence though not the nature of the unrecognisable, to know that a man must be ill or in pain when all the tests are negative. But it is only possible to those who come to their task in a spirit of humility. In the main the diagnosis of 'hysteria' applies to a disorder of the doctor–patient relationship. It is evidence of non-communication, of a mutual misunderstanding ... We are, often, unwilling to tell the full truth or to admit to ignorance ... Evasions, even untruths, on the doctor's side are among the most powerful and frequently used methods he has for bringing about an efflorescence of 'hysteria'".

Much recent work has been done to identify the underlying causes of conversion and related disorders and to better understand why conversion disorder and hysteria appear more commonly in women. Current theoreticians tend to believe there is no single cause for these disorders. Instead, the emphasis tends to be on the patient's understanding and a variety of psychotherapeutic techniques. In some cases, the onset of conversion disorder correlates to a traumatic or stressful event. There are also certain populations that are considered at risk for conversion disorder, including people with a medical illness or condition, people with personality disorders or dissociative identity disorder. However, no biomarkers have yet been found to support the idea that conversion disorder is caused by a psychiatric condition.

There has been much recent interest in using functional neuroimaging to study conversion. As researchers identify the mechanisms which underlie conversion symptoms, it is hoped they will enable the development of a neuropsychological model. A number of such studies have been performed, including some which suggest the blood-flow in patients' brains may be abnormal while they are unwell. However, the studies have all been too small to be confident of the generalisability of their findings, so no neuropsychological model has been clearly established.

An evolutionary psychology explanation for conversion disorder is that the symptoms may have been evolutionarily advantageous during warfare. A non-combatant with these symptoms signals non-verbally, possibly to someone speaking a different language, that she or he is not dangerous as a combatant and also may be carrying some form of dangerous infectious disease. This can explain that conversion disorder may develop following a threatening situation, that there may be a group effect with many people simultaneously developing similar symptoms (as in mass psychogenic illness), and the gender difference in prevalence.

The Lacanian model accepts conversion disorder as a common phenomenon inherent in specific psychical structures. The higher prevalence of it among women is based on somewhat different intrapsychic relations to the body from those of typical males, which allows the formation of conversion symptoms.