From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Combat stress reaction |

|---|

|

| A U.S. Marine, Pvt. Theodore J. Miller, exhibits a "thousand-yard stare", an unfocused, despondent and weary gaze which is a frequent manifestation of "combat fatigue" |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

|---|

Combat stress reaction (CSR) is acute behavioral

disorganization as a direct result of the trauma of war. Also known as

"combat fatigue", "battle fatigue", or "battle neurosis", it has some

overlap with the diagnosis of acute stress reaction used in civilian psychiatry. It is historically linked to shell shock and can sometimes precurse post-traumatic stress disorder.

Combat stress reaction is an acute reaction that includes a range

of behaviors resulting from the stress of battle that decrease the

combatant's fighting efficiency. The most common symptoms are fatigue,

slower reaction times, indecision, disconnection from one's

surroundings, and the inability to prioritize. Combat stress reaction is

generally short-term and should not be confused with acute stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder,

or other long-term disorders attributable to combat stress, although

any of these may commence as a combat stress reaction. The US Army uses

the term/initialism COSR (Combat Stress Reaction) in official medical

reports. This term can be applied to any stress reaction in the military

unit environment. Many reactions look like symptoms of mental illness

(such as panic, extreme anxiety, depression, and hallucinations), but

they are only transient reactions to the traumatic stress of combat and

the cumulative stresses of military operations.

In World War I, shell shock was considered a psychiatric illness resulting from injury to the nerves during combat. The nature of trench warfare meant that about 10% of the fighting soldiers were killed (compared to 4.5% during World War II) and the total proportion of troops who became casualties (killed or wounded) was about 57%.

Whether a person with shell-shock was considered "wounded" or "sick"

depended on the circumstances. Soldiers were personally faulted for

their mental breakdown rather than their war experience. The large

proportion of World War I veterans in the European population meant that the symptoms were common to the culture.

Signs and symptoms

Combat stress reaction symptoms align with the symptoms also found in psychological trauma, which is closely related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). CSR differs from PTSD (among other things) in that a PTSD diagnosis requires a duration of symptoms over one month, which CSR does not.

Fatigue-related symptoms

The most common stress reactions include:

- The slowing of reaction time

- Slowness of thought

- Difficulty prioritizing tasks

- Difficulty initiating routine tasks

- Preoccupation with minor issues and familiar tasks

- Indecision and lack of concentration

- Loss of initiative with fatigue

- Exhaustion

Autonomic nervous system – Autonomic arousal

Battle casualty rates

The

ratio of stress casualties to battle casualties varies with the

intensity of the fighting. With intense fighting, it can be as high as

1:1. In low-level conflicts, it can drop to 1:10 (or less).

Modern warfare embodies the principles of continuous operations with an

expectation of higher combat stress casualties.

The World War II European Army rate of stress casualties of 1 in

10 (101:1,000) troops per annum is skewed downward from both its norm

and peak by data by low rates during the last years of the war.

Diagnosis

The following PIE principles were in place for the "not yet diagnosed nervous" (NYDN) cases:

- Proximity – treat the casualties close to the front and within sound of the fighting.

- Immediacy – treat them without delay and not wait until the wounded were all dealt with.

- Expectancy – ensure that everyone had the expectation of their return to the front after a rest and replenishment.

United States medical officer Thomas W. Salmon is often quoted as the

originator of these PIE principles. However, his real strength came

from going to Europe and learning from the Allies and then instituting

the lessons. By the end of the war, Salmon had set up a complete system

of units and procedures that was then the "world's best practice". After the war, he maintained his efforts in educating society and the military. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his contributions.

Effectiveness of the PIE approach has not been confirmed by

studies of CSR, and there is some evidence that it is not effective in

preventing PTSD.

US services now use the more recently developed BICEPS principles:

- Brevity

- Immediacy

- Centrality or contact

- Expectancy

- Proximity

- Simplicity

Between the wars

The British government produced a Report of the War Office Committee of Inquiry into "Shell-Shock", which was published in 1922. Recommendations from this included:

- In forward areas

- No soldier should be allowed to think that loss of nervous or mental

control provides an honorable avenue of escape from the battlefield,

and every endeavor should be made to prevent slight cases leaving the

battalion or divisional area, where treatment should be confined to

provision of rest and comfort for those who need it and to heartening

them for return to the front line.

- In neurological centers

- When cases are sufficiently severe to necessitate more scientific

and elaborate treatment they should be sent to special Neurological

Centers as near the front as possible, to be under the care of an expert

in nervous disorders. No such case should, however, be so labelled on

evacuation as to fix the idea of nervous breakdown in the patient's

mind.

- In base hospitals

- When evacuation to the base hospital is necessary, cases should be

treated in a separate hospital or separate sections of a hospital, and

not with the ordinary sick and wounded patients. Only in exceptional

circumstances should cases be sent to the United Kingdom, as, for

instance, men likely to be unfit for further service of any kind with

the forces in the field. This policy should be widely known throughout

the Force.

- Forms of treatment

- The establishment of an atmosphere of cure is the basis of all

successful treatment, the personality of the physician is, therefore, of

the greatest importance. While recognizing that each individual case

of war neurosis must be treated on its merits, the Committee are of

opinion that good results will be obtained in the majority by the

simplest forms of psycho-therapy, i.e., explanation, persuasion and

suggestion, aided by such physical methods as baths, electricity and

massage. Rest of mind and body is essential in all cases.

- The committee are of opinion that the production of deep

hypnotic sleep, while beneficial as a means of conveying suggestions or

eliciting forgotten experiences are useful in selected cases, but in the

majority they are unnecessary and may even aggravate the symptoms for a

time.

- They do not recommend psycho-analysis in the Freudian sense.

- In the state of convalescence, re-education and suitable

occupation of an interesting nature are of great importance. If the

patient is unfit for further military service, it is considered that

every endeavor should be made to obtain for him suitable employment on

his return to active life.

- Return to the fighting line

- Soldiers should not be returned to the fighting line under the following conditions:

- (1) If the symptoms of neurosis are of such a character that the

soldier cannot be treated overseas with a view to subsequent useful

employment.

- (2) If the breakdown is of such severity as to necessitate a long period of rest and treatment in the United Kingdom.

- (3) If the disability is anxiety neurosis of a severe type.

- (4) If the disability is a mental breakdown or psychosis requiring treatment in a mental hospital.

- It is, however, considered that many of such cases could, after

recovery, be usefully employed in some form of auxiliary military duty.

Part of the concern was that many British veterans were receiving pensions and had long-term disabilities.

By 1939, some 120,000 British ex-servicemen had received final

awards for primary psychiatric disability or were still drawing

pensions – about 15% of all pensioned disabilities – and another 44,000

or so were getting pensions for 'soldier's heart' or Effort Syndrome.

There is, though, much that statistics do not show, because in terms

of psychiatric effects, pensioners were just the tip of a huge iceberg."

War correspondent Philip Gibbs wrote:

Something was wrong. They put on

civilian clothes again and looked to their mothers and wives very much

like the young men who had gone to business in the peaceful days before

August 1914. But they had not come back the same men. Something had

altered in them. They were subject to sudden moods, and queer tempers,

fits of profound depression alternating with a restless desire for pleasure. Many were easily moved to passion where they lost control of themselves, many were bitter in their speech, violent in opinion, frightening.

One British writer between the wars wrote:

There should be no excuse given for

the establishment of a belief that a functional nervous disability

constitutes a right to compensation. This is hard saying. It may seem

cruel that those whose sufferings are real, whose illness has been

brought on by enemy action and very likely in the course of patriotic

service, should be treated with such apparent callousness. But there

can be no doubt that in an overwhelming proportion of cases, these

patients succumb to 'shock' because they get something out of it. To

give them this reward is not ultimately a benefit to them because it

encourages the weaker tendencies in their character. The nation cannot

call on its citizens for courage and sacrifice and, at the same time,

state by implication that an unconscious cowardice or an unconscious

dishonesty will be rewarded.

World War II

American

At the outbreak of World War II,

most in the United States military had forgotten the treatment lessons

of World War I. Screening of applicants was initially rigorous, but

experience eventually showed it to lack great predictive power.

The US entered the war in December 1941. Only in November 1943 was a psychiatrist added to the table of organization of each division, and this policy was not implemented in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations

until March 1944. By 1943, the US Army was using the term "exhaustion"

as the initial diagnosis of psychiatric cases, and the general

principles of military psychiatry were being used. General Patton's slapping incident was in part the spur to institute forward treatment for the Italian invasion of September 1943. The importance of unit cohesion and membership of a group as a protective factor emerged.

John Appel found that the average American infantryman in Italy

was "worn out" in 200 to 240 days and concluded that the American

soldier "fights for his buddies or because his self respect won't let

him quit". After several months in combat, the soldier lacked reasons to

continue to fight because he had proven his bravery in battle and was

no longer with most of the fellow soldiers he trained with. Appel helped implement a 180-day limit for soldiers in active combat

and suggested that the war be made more meaningful, emphasizing their

enemies' plans to conquer the United States, encouraging soldiers to

fight to prevent what they had seen happen in other countries happen to

their families. Other psychiatrists believed that letters from home

discouraged soldiers by increasing nostalgia and needlessly mentioning

problems soldiers could not solve. William Menninger said after the war, "It might have been wise to have had a nation-wide educational course in letter writing to soldiers", and Edward Strecker criticized "moms" (as opposed to mothers) who, after failing to "wean" their sons, damaged morale through letters.

Airmen flew far more often in the Southwest Pacific than in

Europe, and although rest time in Australia was scheduled, there was no

fixed number of missions that would produce transfer out of combat, as

was the case in Europe. Coupled with the monotonous, hot, sickly

environment, the result was bad morale that jaded veterans quickly

passed along to newcomers. After a few months, epidemics of combat

fatigue would drastically reduce the efficiency of units. Flight surgeons reported that the men who had been at jungle airfields longest were in bad shape:

- Many have chronic dysentery or other disease, and almost

all show chronic fatigue states. … They appear listless, unkempt,

careless, and apathetic with almost mask-like facial expression. Speech

is slow, thought content is poor, they complain of chronic headaches,

insomnia, memory defect, feel forgotten, worry about themselves, are

afraid of new assignments, have no sense of responsibility, and are

hopeless about the future.

British

Unlike

the Americans, the British leaders firmly held the lessons of World War

I. It was estimated that aerial bombardment would kill up to 35,000 a

day, but the Blitz

killed only 40,000 in total. The expected torrent of civilian mental

breakdown did not occur. The Government turned to World War I doctors

for advice on those who did have problems. The PIE principles were

generally used. However, in the British Army,

since most of the World War I doctors were too old for the job, young,

analytically trained psychiatrists were employed. Army doctors "appeared

to have no conception of breakdown in war and its treatment, though

many of them had served in the 1914–1918 war." The first Middle East

Force psychiatric hospital was set up in 1942. With D-Day for the first month there was a policy of holding casualties for only 48 hours before they were sent back over the Channel. This went firmly against the expectancy principle of PIE.

Appel believed that British soldiers were able to continue to

fight almost twice as long as their American counterparts because the

British had better rotation schedules and because they, unlike the

Americans, "fight for survival" – for the British soldiers, the threat

from the Axis powers

was much more real, given Britain's proximity to mainland Europe, and

the fact that Germany was concurrently conducting air raids and

bombarding British industrial cities. Like the Americans, British

doctors believed that letters from home often needlessly damaged

soldiers' morale.

Canadian

The

Canadian Army recognized combat stress reaction as "Battle Exhaustion"

during the Second World War and classified it as a separate type of

combat wound. Historian Terry Copp has written extensively on the

subject.

In Normandy, "The infantry units engaged in the battle also experienced

a rapid rise in the number of battle exhaustion cases with several

hundred men evacuated due to the stress of combat. Regimental Medical

Officers were learning that neither elaborate selection methods nor

extensive training could prevent a considerable number of combat

soldiers from breaking down."

Germans

In his history of the pre-Nazi Freikorps paramilitary organizations, Vanguard of Nazism, historian Robert G. L. Waite describes some of the emotional effects of World War I on German troops, and refers to a phrase he attributes to Göring: men who could not become "de-brutalized".

In an interview, Dr Rudolf Brickenstein stated that:

... he believed that there were no

important problems due to stress breakdown since it was prevented by the

high quality of leadership. But, he added, that if a soldier did break

down and could not continue fighting, it was a leadership problem, not

one for medical personnel or psychiatrists. Breakdown (he said) usually

took the form of unwillingness to fight or cowardice.

However, as World War II progressed there was a profound rise in

stress casualties from 1% of hospitalizations in 1935 to 6% in 1942. Another German psychiatrist reported after the war that during the last

two years, about a third of all hospitalizations at Ensen were due to

war neurosis. It is probable that there was both less of a true problem

and less perception of a problem.

Finns

The Finnish

attitudes to "war neurosis" were especially tough. Psychiatrist Harry

Federley, who was the head of the Military Medicine, considered shell

shock as a sign of weak character and lack of moral fibre. His treatment

for war neurosis was simple: the patients were to be bullied and

harassed until they returned to front line service.

Earlier, during the Winter War,

several Finnish machine gun operators on the Karelian Isthmus theatre

became mentally unstable after repelling several unsuccessful Soviet human wave assaults on fortified Finnish positions.

Post-World War II developments

Simplicity was added to the PIE principles by the Israelis: in their view, treatment should be brief, supportive, and could be provided by those without sophisticated training.

Peacekeeping stresses

Peacekeeping provides its own stresses because its emphasis on rules of engagement contains the roles for which soldiers are trained. Causes include witnessing or experiencing the following:

- Constant tension and threat of conflict.

- Threat of land mines and booby traps.

- Close contact with severely injured and dead people.

- Deliberate maltreatment and atrocities, possibly involving civilians.

- Cultural issues.

- Separation and home issues.

- Risk of disease including HIV.

- Threat of exposure to toxic agents.

- Mission problems.

- Return to service.

Pathophysiology

SNS activation

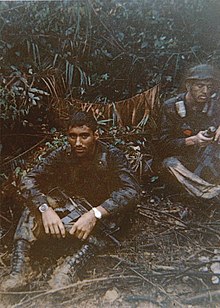

A U.S. Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol leader in Vietnam, 1968.

Many of the symptoms initially experienced by people with CSR are effects of an extended activation of the human body's fight-or-flight response. The fight-or-flight response involves a general sympathetic nervous system discharge in reaction to a perceived stressor and prepares the body to fight or run from the threat causing the stress. Catecholamine hormones, such as adrenaline or noradrenaline, facilitate immediate physical reactions associated with a preparation for violent muscular

action. Although the flight-or-fight-response normally ends with the

removal of the threat, the constant mortal danger in combat zones

likewise constantly and acutely stresses soldiers.

General adaptation syndrome

The process whereby the human body responds to extended stress is known as general adaptation syndrome

(GAS). After the initial fight-or-flight response, the body becomes

more resistant to stress in an attempt to dampen the sympathetic nervous

response and return to homeostasis. During this period of resistance,

physical and mental symptoms of CSR may be drastically reduced as the

body attempts to cope with the stress. Long combat involvement, however,

may keep the body from homeostasis and thereby deplete its resources

and render it unable to normally function, sending it into the third

stage of GAS: exhaustion. Sympathetic nervous activation remains in the

exhaustion phase and reactions to stress are markedly sensitized as

fight-or-flight symptoms return. If the body remains in a state of

stress, then such more severe symptoms of CSR as cardiovascular and

digestive involvement may present themselves. Extended exhaustion can

permanently damage the body.

Treatment

7 Rs

The British Army treated Operational Stress Reaction according to the 7 R's:

- Recognition – identify that the individual has an Operational Stress Reaction

- Respite – provide a short period of relief from the front line

- Rest – allow rest and recovery

- Recall – give the individual the chance to recall and discuss the experiences that have led to the reaction

- Reassurance – inform them that their reaction is normal and they will recover

- Rehabilitation – improve the physical and mental health of the patient until they no longer show symptoms

- Return – allow the soldier to return to their unit

BICEPS

Modern

front-line combat stress treatment techniques are designed to mimic the

historically used PIE techniques with some modification. BICEPS is the

current treatment route employed by the U.S. military and stresses

differential treatment by the severity of CSR symptoms present in the

service member. BICEPS is employed as a means to treat CSR symptoms and

return soldiers quickly to combat.

The following subsections on the BICEPS program are adapted from the USMC combat stress handbook:

Brevity

Critical Event Debriefing should take 2 to 3 hours. Initial rest and

replenishment at medical CSC (Combat Stress Control) facilities should

last no more than 3 or 4 days. Those requiring further treatment are

moved to the next level of care. Since many require no further

treatment, military commanders expect their service members to return to

duty rapidly.

Immediacy

CSC should be done as soon as possible when operations permit. Intervention is provided as soon as symptoms appear.

Centrality/Contact

Service members requiring observation or care beyond the unit level

are evacuated to facilities in close proximity to, but separate from the

medical or surgical patients at the BAS, surgical support company in a

central location (Marines) or forward support/division support or area

support medical companies (Army) nearest the service members' unit. It

is best to send service members who cannot continue their mission and

require more extensive respite to a central facility other than a

hospital, unless no other alternative is possible. The service member

must be encouraged to continue to think of themselves as a war fighter,

rather than a patient or a sick person. The chain of command remains

directly involved in the service member's recovery and return to duty.

The CSC team coordinates with the unit's leaders to learn whether the

over-stressed individual was a good performer prior to the combat stress

reaction, or whether they were always a marginal or problem performer

whom the team would rather see replaced than returned. Whenever

possible, representatives of the unit, or messages from the unit, tell

the casualty that they are needed and wanted back. The CSC team

coordinates with the unit leaders, through unit medical personnel or

chaplains, any special advice on how to assure quick reintegration when

the service member returns to their unit.

Expectancy

The individual is explicitly told that he is reacting normally to

extreme stress and is expected to recover and return to full duty in a

few hours or days. A military leader is extremely effective in this area

of treatment. Of all the things said to a service member experiencing

combat stress, the words of his small-unit leader have the greatest

impact due to the positive bonding process that occurs during combat.

Simple statements from the small-unit leader to the service member that

he is reacting normally to combat stress and is expected back soon have

positive impact. Small-unit leaders should tell service members that

their comrades need and expect them to return. When they do return, the

unit treats them as every other service member and expects them to

perform well. Service members experiencing and recovering from combat

stress disorder are no more likely to become overloaded again than are

those who have not yet been overloaded. In fact, they are less likely to

become overloaded than inexperienced replacements.

Proximity

In mobile war requiring rapid and frequent movement, treatment of

many combat stress cases takes place at various battalion or regimental

headquarters or logistical

units, on light duty, rather than in medical units, whenever possible.

This is a key factor and another area where the small-unit leader helps

in the treatment. CSC and follow-up care for combat stress casualties

are held as close as possible to and maintain close association with the

member's unit, and are an integral part of the entire healing process. A

visit from a member of the individual's unit during restoration is

effective in keeping a bond with the organization.

A service member experiencing combat stress reaction is having a

crisis, and there are two basic elements to that crisis working in

opposite directions. On the one hand, the service member is driven by a

strong desire to seek safety and to get out of an intolerable

environment. On the other hand, the service member does not want to let

their comrades down. They want to return to their unit. If a service

member starts to lose contact with their unit when he enters treatment,

the impulse to get out of the war and return to safety takes over. They

feel that they've failed their comrades who have already rejected them

as unworthy. The potential is for the service member to become more and

more emotionally invested in keeping their symptoms so they can stay in a

safe environment. Much of this is done outside the service member's

conscious awareness, but the result is the same. The more out of touch

the service member is with their unit, the less likely they will

recover. They are more likely to develop a chronic psychiatric illness

and get evacuated from the war.

Simplicity

Treatment is kept simple. CSC is not therapy. Psychotherapy is not

done. The goal is to rapidly restore the service member's coping skills

so that he functions and returns to duty again. Sleep, food, water,

hygiene, encouragement, work details, and confidence-restoring talk are

often all that is needed to restore a service member to full operational

readiness. This can be done in units in reserve positions, logistical

units or at medical companies. Every effort is made to reinforce service

members' identity. They are required to wear their uniforms and to keep

their helmets, equipment, chemical protective gear, and flak jackets

with them. When possible, they are allowed to keep their weapons after

the weapons have been cleared. They may serve on guard duty or as

members of a standby quick reaction force.

Predeployment preparation

Screening

Historically,

screening programs that have attempted to preclude soldiers exhibiting

personality traits thought to predispose them to CSR have been a total

failure. Part of this failure stems from the inability to base CSR

morbidity on one or two personality traits. Full psychological work-ups

are expensive and inconclusive, while pen and paper tests are

ineffective and easily faked. In addition, studies conducted following

WWII screening programs showed that psychological disorders present

during military training did not accurately predict stress disorders

during combat.

Cohesion

While

it is difficult to measure the effectiveness of such a subjective term,

soldiers who reported in a WWII study that they had a "higher than

average" sense of camaraderie and pride in their unit were more likely

to report themselves ready for combat and less likely to develop CSR or

other stress disorders. Soldiers with a "lower than average" sense of

cohesion with their unit were more susceptible to stress illness.

Training

Stress

exposure training or SET is a common component of most modern military

training. There are three steps to an effective stress exposure program.

- Providing knowledge of the stress environment

Soldiers with a knowledge of both the emotional and physical signs

and symptoms of CSR are much less likely to have a critical event that

reduces them below fighting capability. Instrumental information, such

as breathing exercises that can reduce stress and suggestions not to

look at the faces of enemy dead, is also effective at reducing the

chance of a breakdown.

Cognitive control strategies can be taught to soldiers to help them

recognize stressful and situationally detrimental thoughts and repress

those thoughts in combat situations. Such skills have been shown to

reduce anxiety and improve task performance.

- Confidence building through application and practice

Soldiers who feel confident in their own abilities and those of their

squad are far less likely to develop combat stress reaction. Training

in stressful conditions that mimic those of an actual combat situation

builds confidence in the abilities of themselves and the squad. As this

training can actually induce some of the stress symptoms it seeks to

prevent, stress levels should be increased incrementally as to allow the

soldiers time to adapt.

Prognosis

Figures from the 1982 Lebanon war

showed that with proximal treatment, 90% of CSR casualties returned to

their unit, usually within 72 hours. With rearward treatment, only 40%

returned to their unit. It was also found that treatment efficacy went

up with the application of a variety of front line treatment principles

versus just one treatment.

In Korea, similar statistics were seen, with 85% of US battle fatigue

casualties returned to duty within three days and 10% returned to

limited duties after several weeks.

Though these numbers seem to promote the claims that proximal PIE

or BICEPS treatment is generally effective at reducing the effects of

combat stress reaction, other data suggests that long term PTSD effects

may result from the hasty return of affected individuals to combat. Both

PIE and BICEPS are meant to return as many soldiers as possible to

combat, and may actually have adverse effects on the long-term health of

service members who are rapidly returned to the front-line after combat

stress control treatment. Although the PIE principles were used

extensively in the Vietnam War, the post traumatic stress disorder

lifetime rate for Vietnam veterans was 30% in a 1989 US study and 21% in

a 1996 Australian study. In a study of Israeli Veterans of the 1973 Yom

Kippur War, 37% of veterans diagnosed with CSR during combat were later

diagnosed with PTSD, compared with 14% of control veterans.

Controversy

There

is significant controversy with the PIE and BICEPS principles.

Throughout a number of wars, but notably during the Vietnam War, there

has been a conflict among doctors about sending distressed soldiers back

to combat. During the Vietnam War this reached a peak with much

discussion about the ethics of this process. Proponents of the PIE and

BICEPS principles argue that it leads to a reduction of long-term

disability but opponents argue that combat stress reactions lead to

long-term problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

The use of psychiatric drugs to treat people with CSR has also

attracted criticism, as some military psychiatrists have come to

question the efficacy of such drugs on the long-term health of veterans.

Concerns have been expressed as to the effect of pharmaceutical

treatment on an already elevated substance abuse rate among former

people with CSR.

Recent research has caused an increasing number of scientists to

believe that there may be a physical (i.e., neurocerebral damage) rather

than psychological basis for blast trauma. As traumatic brain injury

and combat stress reaction have very different causes yet result in

similar neurologic symptoms, researchers emphasize the need for greater

diagnostic care.