From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executive_dysfunction

Executive functioning

is a theoretical construct representing a domain of cognitive processes

that regulate, control, and manage other cognitive processes. Executive

functioning is not a unitary concept; it is a broad description of the

set of processes involved in certain areas of cognitive and behavioural

control. Executive processes are integral to higher brain function, particularly in the areas of goal formation, planning, goal-directed action, self-monitoring, attention, response inhibition, and coordination of complex cognition and motor control for effective performance.

Deficits of the executive functions are observed in all populations to

varying degrees, but severe executive dysfunction can have devastating

effects on cognition and behaviour in both individual and social

contexts on a day to day basis.

Executive dysfunction does occur to a minor degree in all

individuals on both short-term and long-term scales. In non-clinical

populations, the activation of executive processes appears to inhibit

further activation of the same processes, suggesting a mechanism for

normal fluctuations in executive control. Decline in executive functioning is also associated with both normal and clinical aging.

The decline of memory processes as people age appears to affect

executive functions, which also points to the general role of memory in

executive functioning.

Executive dysfunction appears to consistently involve disruptions

in task-oriented behavior, which requires executive control in the

inhibition of habitual responses and goal activation.

Such executive control is responsible for adjusting behaviour to

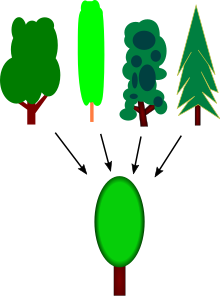

reconcile environmental changes with goals for effective behaviour. Impairments in set shifting

ability are a notable feature of executive dysfunction; set shifting is

the cognitive ability to dynamically change focus between points of

fixation based on changing goals and environmental stimuli. This offers a parsimonious explanation for the common occurrence of impulsive, hyperactive, disorganized, and aggressive behaviour

in clinical patients with executive dysfunction. A recent study

confirms there is a lack of self-control, greater impulsivity, and

greater disorganization with executive dysfunction, leading to greater

amounts of aggressive behavior.

Executive dysfunction, particularly in working memory capacity, may also lead to varying degrees of emotional dysregulation, which can manifest as chronic depression, anxiety, or hyperemotionality. Russell Barkley proposed a hybrid model of the role of behavioural disinhibition in the presentation of ADHD, which has served as the basis for much research of both ADHD and broader implications of the executive system.

Other common and distinctive symptoms of executive dysfunction include utilization behaviour,

which is compulsive manipulation/use of nearby objects due simply to

their presence and accessibility (rather than a functional reason); and imitation behaviour, a tendency to rely on imitation as a primary means of social interaction. Research also suggests that executive set shifting is a co-mediator with episodic memory of feeling-of-knowing (FOK) accuracy, such that executive dysfunction may reduce FOK accuracy.

There is some evidence suggesting that executive dysfunction may

produce beneficial effects as well as maladaptive ones. Abraham et al. demonstrate that creative thinking in schizophrenia is mediated by executive dysfunction, and they establish a firm etiology

for creativity in psychoticism, pinpointing a cognitive preference for

broader top-down associative thinking versus goal-oriented thinking,

which closely resembles aspects of ADHD. It is postulated that elements

of psychosis are present in both ADHD and schizophrenia/schizotypy due to dopamine overlap.

Cause

The cause of executive dysfunction is heterogeneous, as many neurocognitive

processes are involved in the executive system and each may be

compromised by a range of genetic and environmental factors. Learning

and development of long-term memory play a role in the severity of

executive dysfunction through dynamic interaction with neurological

characteristics. Studies in cognitive neuroscience suggest that

executive functions are widely distributed throughout the brain, though a

few areas have been isolated as primary contributors. Executive

dysfunction is studied extensively in clinical neuropsychology as well,

allowing correlations to be drawn between such dysexecutive symptoms and

their neurological correlates. More recent research confirms that

executive dysfunction has a positive correlation with neurodevelopmental

disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Executive processes are closely integrated with memory retrieval

capabilities for overall cognitive control; in particular,

goal/task-information is stored in both short-term and long-term memory,

and effective performance requires effective storage and retrieval of

this information.

Executive dysfunction characterizes many of the symptoms observed in numerous clinical populations. In the case of acquired brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases there is a clear neurological etiology producing dysexecutive symptoms. Conversely, syndromes and disorders are defined and diagnosed based on their symptomatology rather than etiology. Thus, while Parkinson's disease, a neurodegenerative condition, causes executive dysfunction, a disorder such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

is a classification given to a set of subjectively-determined symptoms

implicating executive dysfunction – current models indicate that such

clinical symptoms are caused by executive dysfunction.

Neurophysiology

As previously mentioned, executive functioning is not a unitary concept.

Many studies have been conducted in an attempt to pinpoint the exact

regions of the brain that lead to executive dysfunction, producing a

vast amount of often conflicting information indicating wide and

inconsistent distribution of such functions. A common assumption is that

disrupted executive control processes are associated with pathology in prefrontal brain regions.

This is supported to some extent by the primary literature, which shows

both pre-frontal activation and communication between the pre-frontal

cortex and other areas associated with executive functions such as the basal ganglia and cerebellum.

In most cases of executive dysfunction, deficits are attributed

to either frontal lobe damage or dysfunction, or to disruption in

fronto-subcortical connectivity. Neuroimaging with PET and fMRI has confirmed the relationship between executive function and functional frontal pathology. Neuroimaging studies have also suggested that some constituent functions are not discretely localized in prefrontal regions.

Functional imaging studies using different tests of executive function

have implicated the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex to be the primary

site of cortical activation during these tasks.

In addition, PET studies of patients with Parkinson's disease have

suggested that tests of executive function are associated with abnormal

function in the globus pallidus and appear to be the genuine result of basal ganglia damage.

With substantial cognitive load, fMRI signals indicate a common

network of frontal, parietal and occipital cortices, thalamus, and the

cerebellum.

This observation suggests that executive function is mediated by

dynamic and flexible networks that are characterized using functional

integration and effective connectivity analyses. The complete circuit underlying executive function includes both a direct and an indirect circuit. The neural circuit responsible for executive functioning is, in fact, located primarily in the frontal lobe. This main circuit originates in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex/orbitofrontal cortex and then projects through the striatum and thalamus to return to the prefrontal cortex.

Not surprisingly, plaques and tangles in the frontal cortex can

cause disruption in functions as well as damage to the connections

between prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus. Another important point is in the finding that structural MRI images link the severity of white matter lesions to deficits in cognition.

The emerging view suggests that cognitive processes materialize

from networks that span multiple cortical sites with closely

collaborative and over-lapping functions.

A challenge for future research will be to map the multiple brain

regions that might combine with each other in a vast number of ways,

depending on the task requirements.

Genetics

Certain

genes have been identified with a clear correlation to executive

dysfunction and related psychopathologies. According to Friedman et al. (2008), the heritability of executive functions is among the highest of any psychological trait. The dopamine receptor D4 gene (DRD4) with 7'-repeating polymorphism

(7R) has been repeatedly shown to correlate strongly with impulsive

response style on psychological tests of executive dysfunction,

particularly in clinical ADHD. The catechol-o-methyl transferase gene (COMT)

codes for an enzyme that degrades catecholamine neurotransmitters (DA

and NE), and its Val158Met polymorphism is linked with the modulation of

task-oriented cognition and behavior (including set shifting)

and the experience of reward, which are major aspects of executive

functioning. COMT is also linked to methylphenidate (stimulant

medication) response in children with ADHD.

Both the DRD4/7R and COMT/Val158Met polymorphisms are also correlated

with executive dysfunction in schizophrenia and schizotypal behaviour.

Testing and measurement

There

are several measures that can be employed to assess the executive

functioning capabilities of an individual. Although a trained

non-professional working outside of an institutionalized setting can

legally and competently perform many of these measures, a trained

professional administering the test in a standardized setting will yield

the most accurate results.

Clock drawing test

The

Clock drawing test (CDT) is a brief cognitive task that can be used by

physicians who suspect neurological dysfunction based on history and

physical examination. It is relatively easy to train non-professional

staff to administer a CDT. Therefore, this is a test that can easily be

administered in educational and geriatric settings and can be utilized

as a precursory measure to indicate the likelihood of further/future

deficits. Also, generational, educational and cultural differences are not perceived as impacting the utility of the CDT.

The procedure of the CDT begins with the instruction to the

participant to draw a clock reading a specific time (generally 11:10).

After the task is complete, the test administrator draws a clock with

the hands set at the same specific time. Then the patient is asked to

copy the image.

Errors in clock drawing are classified according to the following

categories: omissions, perseverations, rotations, misplacements,

distortions, substitutions and additions. Memory, concentration, initiation, energy, mental clarity and indecision are all measures that are scored during this activity. Those with deficits in executive functioning will often make errors on the first clock but not the second. In other words, they will be unable to generate their own example, but will show proficiency in the copying task.

Stroop task

The cognitive mechanism involved in the Stroop task

is referred to as directed attention. The Stroop task requires the

participant to engage in and allows assessment of processes such as

attention management, speed and accuracy of reading words and colours

and of inhibition of competing stimuli.

The stimulus is a colour word that is printed in a different colour

than what the written word reads. For example, the word "red" is written

in a blue font. One must verbally classify the colour that the word is

displayed/printed in, while ignoring the information provided by the

written word. In the aforementioned example, this would require the

participant to say "blue" when presented with the stimulus. Although the

majority of people will show some slowing when given incompatible text

versus font colour, this is more severe in individuals with deficits in

inhibition. The Stroop task takes advantage of the fact that most humans

are so proficient at reading colour words that it is extremely

difficult to ignore this information, and instead acknowledge, recognize

and say the colour the word is printed in. The Stroop task is an assessment of attentional vitality and flexibility. More modern variations of the Stroop task tend to be more difficult and often try to limit the sensitivity of the test.

Wisconsin card sorting test

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

(WCST) is used to determine an individual's competence in abstract

reasoning, and the ability to change problem-solving strategies when

needed. These abilities are primarily determined by the frontal lobes and basal ganglia, which are crucial components of executive functioning; making the WCST a good measure for this purpose.

The WCST utilizes a deck of 128 cards that contains four stimulus cards.

The figures on the cards differ with respect to color, quantity, and

shape. The participants are then given a pile of additional cards and

are asked to match each one to one of the previous cards. Typically,

children between ages 9 and 11 are able to show the cognitive flexibility that is needed for this test.

Trail-making test

Another prominent test of executive dysfunction is known as the Trail-making test.

This test is composed of two main parts (Part A & Part B). Part B

differs from Part A specifically in that it assesses more complex

factors of motor control and perception.

Part B of the Trail-making test consists of multiple circles containing

letters (A-L) and numbers (1-12). The participant's objective for this

test is to connect the circles in order, alternating between number and

letter (e.g. 1-A-2-B) from start to finish.

The participant is required not to lift their pencil from the page. The

task is also timed as a means of assessing speed of processing.

Set-switching tasks in Part B have low motor and perceptual selection

demands, and therefore provide a clearer index of executive function.

Throughout this task, some of the executive function skills that are

being measured include impulsivity, visual attention and motor speed.

In clinical populations

The

executive system's broad range of functions relies on, and is

instrumental in, a broad range of neurocognitive processes. Clinical

presentation of severe executive dysfunction that is unrelated to a

specific disease or disorder is classified as a dysexecutive syndrome, and often appears following damage to the frontal lobes of the cerebral cortex. As a result, executive dysfunction is implicated etiologically and/or co-morbidly

in many psychiatric illnesses, which often show the same symptoms as

the dysexecutive syndrome. It has been assessed and researched

extensively in relation to cognitive developmental disorders, psychotic disorders, affective disorders, and conduct disorders, as well as neurodegenerative diseases and acquired brain injury (ABI).

Environmental dependency syndrome is a dysexecutive syndrome

marked by significant behavioural dependence on environmental cues and

is marked by excessive imitation and utilization behaviour. It has been observed in patients with a variety of etiologies including ABI, exposure to phendimetrazine tartrate, stroke, and various frontal lobe lesions.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia

is commonly described as a mental disorder in which a person becomes

detached from reality because of disruptions in the pattern of thinking

and perception.

Although the etiology is not completely understood, it is closely

related to dopaminergic activity and is strongly associated with both

neurocognitive and genetic elements of executive dysfunction. Individuals with schizophrenia may demonstrate amnesia for portions of their episodic memory.

Observed damage to explicit, consciously accessed, memory is generally

attributed to the fragmented thoughts that characterize the disorder.

These fragmented thoughts are suggested to produce a similarly

fragmented organization in memory during encoding and storage, making

retrieval more difficult. However, implicit memory is generally preserved in patients with schizophrenia.

Patients with schizophrenia demonstrate spared performance on

measures of visual and verbal attention and concentration, as well as on

immediate digit span recall, suggesting that observed deficits cannot

be attributed to deficits in attention or short-term memory.

However, impaired performance was measured on psychometric measures

assumed to assess higher order executive function. Working memory and

multi-tasking impairments typically characterize the disorder. Persons with schizophrenia also tend to demonstrate deficits in response inhibition and cognitive flexibility.

Patients often demonstrate noticeable deficits in the central executive component of working memory as conceptualized by Baddeley and Hitch. However, performance on tasks associated with the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad are typically less affected.

More specifically, patients with schizophrenia show impairment to the

central executive component of working memory, specific to tasks in

which the visuospatial system is required for central executive control. The phonological system appears to be more generally spared overall.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

A triad of core symptoms – inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity – characterize attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

(ADHD). Individuals with ADHD often experience problems with

organization, discipline, and setting priorities, and these difficulties

often persist from childhood through adulthood.

In both children and adults with ADHD, an underlying executive

dysfunction involving the prefrontal regions and other interconnected

subcortical structures has been found.

As a result, people with ADHD commonly perform more poorly than matched

controls on interference control, mental flexibility and verbal

fluency. Also, a more central impairment in self-regulation is noted in cases of ADHD.

However, some research has suggested the possibility that the severity

of executive dysfunction in individuals with ADHD declines with age as

they learn to compensate for the aforementioned deficits.

Thus, a decrease in executive dysfunction in adults with ADHD as

compared to children with ADHD is thought reflective of compensatory

strategies employed on behalf of the adults (e.g. using schedules to

organize tasks) rather than neurological differences.

Although ADHD has typically been conceptualized in a categorical

diagnostic paradigm, it has also been proposed that this disorder should

be considered within a more dimensional behavioural model that links

executive functions to observed deficits.

Proponents argue that classic conceptions of ADHD falsely localize the

problem at perception (input) rather than focusing on the inner

processes involved in producing appropriate behaviour (output).

Moreover, others have theorized that the appropriate development of

inhibition (something that is seen to be lacking in individuals with

ADHD) is essential for the normal performance of other

neuropsychological abilities such as working memory, and emotional

self-regulation.

Thus, within this model, deficits in inhibition are conceptualized to

be developmental and the result of atypically operating executive

systems.

Autism spectrum disorder

Autism

is diagnosed based on the presence of markedly abnormal or impaired

development in social interaction and communication and a markedly

restricted or repetitive repertoire of stereotypic movements,

activities, and/or interests. It is a disorder that is defined according

to behaviour as no specific biological markers are known.

Due to the variability in severity and impairment in functioning

exhibited by autistic people, the disorder is typically conceptualized

as existing along a continuum (or spectrum) of severity.

Autistic individuals commonly show impairment in three main areas of executive functioning:

- Fluency. Fluency refers to the ability to generate novel

ideas and responses. Although adult populations are largely

underrepresented in this area of research, findings have suggested that

autistic children generate fewer novel words and ideas and produce less

complex responses than matched controls.

- Planning. Planning refers to a complex, dynamic process,

wherein a sequence of planned actions must be developed, monitored,

re-evaluated and updated. Autistic persons demonstrate impairment on

tasks requiring planning abilities relative to typically functioning

controls, with this impairment maintained over time. As might be

suspected, in the case of autism comorbid with learning disability, an

additive deficit is observed in many cases.

- Flexibility. Poor mental flexibility, as demonstrated in

autistic individuals, is characterized by perseverative, stereotyped

behaviour, and deficits in both the regulation and modulation of motor

acts. Some research has suggested that autistic individuals experience a

sort of 'stuck-in-set' perseveration that is specific to the disorder,

rather than a more global perseveration tendency. These deficits have

been exhibited in cross-cultural samples and have been shown to persist

over time. Autistic individuals have also been shown to react slower as

well as perform slower in tasks that require mental flexibility when

compared to their neurotypical peers.

Although there has been some debate, inhibition is generally no

longer considered to be an executive function deficit in autistic

people.

Autistic individuals have demonstrated differential performance on

various tests of inhibition, with results being taken to indicate a

general difficulty in the inhibition of a habitual response. However, performance on the Stroop task,

for example, has been unimpaired relative to matched controls. An

alternative explanation has suggested that executive function tests that

demonstrate a clear rationale are passed by autistic individuals.

In this light, it is the design of the measures of inhibition that have

been implicated in the observation of impaired performance rather than

inhibition being a core deficit.

In general, autistic individuals show relatively spared performance on tasks that do not require mentalization.

These include: use of desire and emotion words, sequencing behavioural

pictures, and the recognition of basic facial emotional expressions. In

contrast, autistic individuals typically demonstrated impaired

performance on tasks that do require mentalizing. These include: false beliefs, use of belief and idea words, sequencing mentalistic pictures, and recognizing complex emotions such as scheming.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder

is a mood disorder that is characterized by both highs (mania) and lows

(depression) in mood. These changes in mood sometimes alternate rapidly

(changes within days or weeks) and sometimes not so rapidly (within

weeks or months).

Current research provides strong evidence of cognitive impairments in

individuals with bipolar disorder, particularly in executive function

and verbal learning. Moreover, these cognitive deficits appear to be consistent cross-culturally,

indicating that these impairments are characteristic of the disorder

and not attributable to differences in cultural values, norms, or

practice. Functional neuroimaging studies have implicated abnormalities

in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex

as being volumetrically different in individuals with bipolar disorder.

Individuals affected by bipolar disorder exhibit deficits in

strategic thinking, inhibitory control, working memory, attention, and

initiation that are independent of affective state.

In contrast to the more generalized cognitive impairment demonstrated

in persons with schizophrenia, for example, deficits in bipolar disorder

are typically less severe and more restricted. It has been suggested

that a "stable dys-regulation of prefrontal function or the

subcortical-frontal circuitry [of the brain] may underlie the cognitive

disturbances of bipolar disorder".

Executive dysfunction in bipolar disorder is suggested to be associated

particularly with the manic state, and is largely accounted for in

terms of the formal thought disorder that is a feature of mania. It is important to note, however, that patients with bipolar disorder with a history of psychosis

demonstrated greater impairment on measures of executive functioning

and spatial working memory compared with bipolar patients without a

history of psychosis suggesting that psychotic symptoms are correlated with executive dysfunction.

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease

(PD) primarily involves damage to subcortical brain structures and is

usually associated with movement difficulties, in addition to problems

with memory and thought processes. Persons affected by PD often demonstrate difficulties in working memory,

a component of executive functioning. Cognitive deficits found in early

PD process appear to involve primarily the fronto-executive functions.

Moreover, studies of the role of dopamine in the cognition of PD

patients have suggested that PD patients with inadequate dopamine

supplementation are more impaired in their performance on measures of

executive functioning.

This suggests that dopamine may contribute to executive control

processes. Increased distractibility, problems in set formation and

maintaining and shifting attentional sets, deficits in executive

functions such as self-directed planning, problems solving, and working

memory have been reported in PD patients. In terms of working memory specifically, persons with PD show deficits in the areas of: a) spatial working memory; b) central executive aspects of working memory; c) loss of episodic memories; d) locating events in time.

- Spatial working memory

- PD patients often demonstrate difficulty in updating changes in

spatial information and often become disoriented. They do not keep track

of spatial contextual information in the same way that a typical person

would do almost automatically.

Similarly, they often have trouble remembering the locations of objects

that they have recently seen, and thus also have trouble with encoding

this information into long-term memory.

- Central executive aspects

- PD is often characterized by a difficulty in regulating and

controlling one's stream of thought, and how memories are utilized in

guiding future behaviour. Also, persons affected by PD often demonstrate

perseverative behaviours such as continuing to pursue a goal after it

is completed, or an inability to adopt a new strategy that may be more

appropriate in achieving a goal. However, some research from 2007

suggests that PD patients may actually be less persistent in pursuing

goals than typical persons and may abandon tasks sooner when they

encounter problems of a higher level of difficulty.

- Loss of episodic memories

- The loss of episodic memories in PD patients typically demonstrates a

temporal gradient wherein older memories are generally more preserved

than newer memories. Also, while forgetting event content is less

compromised in Parkinson's than in Alzheimer's, the opposite is true for event data memories.

- Locating events in time

- PD patients often demonstrate deficits in their ability to sequence

information, or date events. Part of the problems is hypothesized to be

due to a more fundamental difficulty in coordinating or planning

retrieval strategies, rather than failure at the level of encoding or

storing information in memory. This deficit is also likely to be due to

an underlying difficulty in properly retrieving script information. PD

patients often exhibit signs of irrelevant intrusions, incorrect

ordering of events, and omission of minor components in their script

retrieval, leading to disorganized and inappropriate application of

script information.

Treatment

Psychosocial treatment

Since

1997, there has been experimental and clinical practice of psychosocial

treatment for adults with executive dysfunction, and particularly

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychosocial treatment

addresses the many facets of executive difficulties, and as the name

suggests, covers academic, occupational and social deficits.

Psychosocial treatment facilitates marked improvements in major symptoms

of executive dysfunction such as time management, organization and

self-esteem.

One kind of psychosocial treatment has been found to be particularly

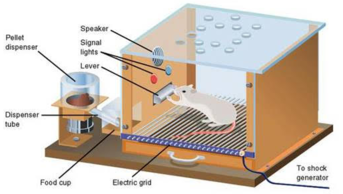

helpful, Behavioral Parent Training (BPT). Behavioral Parent Training

(BPT) helps parents learn, through the help of a trained mental health

professional, how to help their child behave better. This outlines

proper use of reward and punishment with the child, mostly using methods

of positive and negative reinforcement rather than punishment. For

example, taking away a positive reinforcement such as praise, as opposed

to adding a punishment.

Psychosocial treatments are effective for adults with

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as well. One study shows

that there are a number of useful psychosocial interventions that help

adults with ADHD live better lives too. These included mindfulness

training, cognitive based behavioral therapy, as well as education to

help the participants recognize problem behaviors in their lives.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy and group rehabilitation

Cognitive-behavioural therapy

(CBT) is a frequently suggested treatment for executive dysfunction,

but has shown limited effectiveness. However, a study of CBT in a group

rehabilitation setting showed a significant increase in positive

treatment outcome compared with individual therapy. Patients'

self-reported symptoms on 16 different ADHD/executive-related items were

reduced following the treatment period.

Treatment for patients with acquired brain injury

The

use of auditory stimuli has been examined in the treatment of

dysexecutive syndrome. The presentation of auditory stimuli causes an

interruption in current activity, which appears to aid in preventing

"goal neglect" by increasing the patients' ability to monitor time and

focus on goals. Given such stimuli, subjects no longer performed below

their age group average IQ.

Patients with acquired brain injury have also been exposed to

goal management training (GMT). GMT skills are associated with

paper-and-pencil tasks that are suitable for patients having difficulty

setting goals. From these studies there has been support for the

effectiveness of GMT and the treatment of executive dysfunction due to

ABI.

Developmental context

An

understanding of how executive dysfunction shapes development has

implications how we conceptualize executive functions and their role in

shaping the individual. Disorders affecting children such as ADHD, along

with oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, high functioning

autism, and Tourette's syndrome have all been suggested to involve

executive functioning deficits.

The main focus of current research has been on working memory,

planning, set shifting, inhibition, and fluency. This research suggests

that differences exist between typically functioning, matched controls,

and clinical groups, on measures of executive functioning.

Some research has suggested a link between a child's abilities to

gain information about the world around them and having the ability to

override emotions in order to behave appropriately.

One study required children to perform a task from a series of

psychological tests, with their performance used as a measure of

executive function.

The tests included assessments of: executive functions

(self-regulation, monitoring, attention, flexibility in thinking),

language, sensorimotor, visuospatial, and learning, in addition to

social perception. The findings suggested that the development of theory of mind

in younger children is linked to executive control abilities with

development impaired in individuals who exhibit signs of executive

dysfunction.

Both ADHD and obesity are complicated disorders and each produces a large impact on an individual's social well-being.

This being both a physical and psychological disorder has reinforced

that obese individuals with ADHD need more treatment time (with

associated costs), and are at a higher risk of developing physical and

emotional complications.

The cognitive ability to develop a comprehensive self-construct and the

ability to demonstrate capable emotion regulation is a core deficit

observed in people with ADHD and is linked to deficits in executive

function.

Overall, low executive functioning seen in individuals with ADHD has

been correlated with tendencies to overeat, as well as with emotional

eating.

This particular interest in the relationship between ADHD and obesity

is rarely clinically assessed and may deserve more attention in future

research.

It has been made known that young children with behavioral problems show poor verbal ability and executive functions.

The exact distinction between parenting style and the importance of

family structure on child development is still somewhat unclear.

However, in infancy and early childhood, parenting is among the most

critical external influences on child reactivity.

In Mahoney's study of maternal communication, results indicated that

the way mothers interacted with their children accounted for almost 25%

of variability in children's rate of development.

Every child is unique, making parenting an emotional challenge that

should be most closely related to the child's level of emotional

self-regulation (persistence, frustration and compliance).

A promising approach that is currently being investigated amid

intellectually disabled children and their parents is responsive

teaching. Responsive teaching is an early intervention curriculum

designed to address the cognitive, language, and social needs of young

children with developmental problems. Based on the principle of "active learning",

responsive teaching is a method that is currently being applauded as

adaptable for individual caregivers, children and their combined needs

The effect of parenting styles on the development of children is an

important area of research that seems to be forever ongoing and

altering. There is no doubt that there is a prominent link between

parental interaction and child development but the best child-rearing

technique continues to vary amongst experts.

Evolutionary perspective

The

prefrontal lobe controls two related executive functioning domains. The

first is mediation of abilities involved in planning, problem solving,

and understanding information, as well as engaging in working memory

processes and controlled attention. In this sense, the prefrontal lobe

is involved with dealing with basic, everyday situations, especially

those involving metacognitive functions.

The second domain involves the ability to fulfill biological needs

through the coordination of cognition and emotions which are both

associated with the frontal and prefrontal areas.

From an evolutionary perspective, it has been hypothesized that

the executive system may have evolved to serve several adaptive

purposes.

The prefrontal lobe in humans has been associated both with

metacognitive executive functions and emotional executive functions.

Theory and evidence suggest that the frontal lobes in other primates

also mediate and regulate emotion, but do not demonstrate the

metacognitive abilities that are demonstrated in humans.

This uniqueness of the executive system to humans implies that there

was also something unique about the environment of ancestral humans,

which gave rise to the need for executive functions as adaptations to

that environment.

Some examples of possible adaptive problems that would have been solved

by the evolution of an executive system are: social exchange, imitation

and observational learning, enhanced pedagogical understanding, tool

construction and use, and effective communication.

In a similar vein, some have argued that the unique metacognitive

capabilities demonstrated by humans have arisen out of the development

of a sophisticated language (symbolization) systems and culture.

Moreover, in a developmental context, it has been proposed that each

executive function capability originated as a form of public behaviour

directed at the external environment, but then became self-directed, and

then finally, became private to the individual, over the course of the

development of self-regulation.

These shifts in function illustrate the evolutionarily salient strategy

of maximizing longer-term social consequences over near-term ones,

through the development of an internal control of behaviour.

Comorbidity

Flexibility problems are more likely to be related to anxiety, and metacognition problems are more likely to be related to depression.

Socio-cultural implications

Education

In

the classroom environment, children with executive dysfunction

typically demonstrate skill deficits that can be categorized into two

broad domains: a) self-regulatory skills; and b) goal-oriented skills. The table below is an adaptation of McDougall's

summary and provides an overview of specific executive function

deficits that are commonly observed in a classroom environment. It also

offers examples of how these deficits are likely to manifest in

behaviour.

Self-regulatory skills

| Often exhibit deficits in...

|

Manifestations in the classroom

|

| Perception. Awareness of something happening in the environment

|

Doesn't "see" what is happening; Doesn't "hear" instructions

|

| Modulation. Awareness of the amount of effort needed to perform a task (successfully)

|

Commission of errors at easy levels and success at harder levels;

Indication that student thinks the task is "easy" then cannot do it

correctly; Performance improves once the student realized that the task

is more difficult than originally thought

|

| Sustained attention. Ability to focus on a task or situation despite distractions, fatigue or boredom

|

Initiates the task, but doesn't continue to work steadily; Easily

distracted; Fatigues easily; Complains task is too long or too boring

|

| Flexibility. Ability to change focus, adapt to

changing conditions or revise plans in the face of obstacles, new

information or mistakes (can also be considered as "adaptability")

|

Slow to stop one activity and begin another after being instructed

to do so; Tendency to stay with one plan or strategy even after it is

shown to be ineffective; Rigid adherence to routines; Refusal to

consider new information

|

| Working memory. Ability to hold information in memory while performing complex tasks with information

|

Forgets instructions (especially if multi-step); Frequently asks for

information to be repeated; Forgets books at home or at school; Can not

do mental arithmetic; Difficulty making connections with previously learned information; Difficulty with reading comprehension

|

| Response inhibition. Capacity to think before acting (deficits are often observed as "impulsivity")

|

Seems to act without thinking; Frequently interrupts; Talks out in

class; Often out of seat/away from desk; Rough play gets out of control;

Doesn't consider consequences of actions

|

| Emotional regulation. Ability to modulate emotional responses

|

Temper outbursts; Cries easily; Very easily frustrated; Very quick to anger; Acts silly

|

Goal-oriented skills

| Often exhibit deficits in...

|

Manifestations in the classroom

|

| Planning. Ability to list steps needed to reach a goal or complete a task

|

Doesn't know where to start when given large assignments; Easily

overwhelmed by task demands; Difficulty developing a plan for long-term

projects; Problem-solving strategies are very limited and haphazard;

Starts working before adequately considering the demands of a task;

Difficulty listing steps required to complete a task

|

| Organization. Ability to arrange information or materials according to a system

|

Disorganized desk, binder, notebooks, etc.; Loses books, papers,

assignments, etc.; Doesn't write down important information; Difficulty

retrieving information when needed

|

| Time management. Ability to comprehend how much time

is available, or to estimate how long it will take to complete a task,

and keep track of how much time has passed relative to the amount of the

task completed

|

Very little work accomplished during a specified period of time;

Wasting time, then rushing to complete a task at the last minute; Often

late to class/assignments are often late; Difficulty estimating how long

it takes to do a task; Limited awareness of the passage of time

|

| Self-monitoring. Ability to stand back and evaluate how you are doing (can also be thought of as "metacognitive" abilities)

|

Makes "careless" errors; Does not check work before handing it in;

Does not stop to evaluate how things are going in the middle of a task

or activity; Thinks a task was well done, when in fact it was done

poorly; Thinks a task was poorly done, when in fact it was done well

|

Teachers play a crucial role in the implementation of strategies

aimed at improving academic success and classroom functioning in

individuals with executive dysfunction. In a classroom environment, the

goal of intervention

should ultimately be to apply external control, as needed (e.g. adapt

the environment to suit the child, provide adult support) in an attempt

to modify problem behaviours or supplement skill deficits.

Ultimately, executive function difficulties should not be attributed to

negative personality traits or characteristics (e.g. laziness, lack of

motivation, apathy, and stubbornness) as these attributions are neither

useful nor accurate.

Several factors should be considered in the development of

intervention strategies. These include, but are not limited to:

developmental level of the child, comorbid disabilities, environmental

changes, motivating factors, and coaching strategies.

It is also recommended that strategies should take a proactive approach

in managing behaviour or skill deficits (when possible), rather than

adopt a reactive approach.

For example, an awareness of where a student may have difficulty

throughout the course of the day can aid the teacher in planning to

avoid these situations or in planning to accommodate the needs of the

student.

People with executive dysfunction have a slower cognitive

processing speed and thus often take longer to complete tasks than

people who demonstrate typical executive function capabilities. This can

be frustrating for the individual and can serve to impede academic

progress. Disorders affecting children such as ADHD, along with

oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, high functioning autism

and Tourette's syndrome have all been suggested to involve executive

functioning deficits.

The main focus of current research has been on working memory,

planning, set shifting, inhibition, and fluency. This research suggests

that differences exist between typically functioning, matched controls

and clinical groups, on measures of executive functioning.

Moreover, some people with ADHD report experiencing frequent feelings of drowsiness.

This can hinder their attention for lectures, readings, and completing

assignments. Individuals with this disorder have also been found to

require more stimuli for information processing in reading and writing.

Slow processing may manifest in behavior as signaling a lack of

motivation on behalf of the learner. However, slow processing is

reflective of an impairment of the ability to coordinate and integrate

multiple skills and information sources.

The main concern with individuals with autism regarding learning is in the imitation of skills.

This can be a barrier in many aspects such as learning about others

intentions, mental states, speech, language, and general social skills.

Individuals with autism tend to be dependent on the routines that they

have already mastered, and have difficulty with initiating new

non-routine tasks. Although an estimated 25–40% of people with autism

also have a learning disability, many will demonstrate an impressive

rote memory and memory for factual knowledge. As such, repetition is the primary and most successful method for instruction when teaching people with autism.

Being attentive and focused for people with Tourette's syndrome

is a difficult process. People affected by this disorder tend to be

easily distracted and act very impulsively.

That is why it is very important to have a quiet setting with few

distractions for the ultimate learning environment. Focusing is

particularly difficult for those who are affected by Tourette's syndrome

comorbid with other disorders such as ADHD or obsessive-compulsive disorder, it makes focusing very difficult.

Also, these individuals can be found to repeat words or phrases

consistently either immediately after they are learned or after a

delayed period of time.

Criminal behaviour

Prefrontal dysfunction has been found as a marker for persistent, criminal behavior. The prefrontal cortex is involved with mental functions including; affective range of emotions, forethought, and self-control.

Moreover, there is a scarcity of mental control displayed by

individuals with a dysfunction in this area over their behavior, reduced

flexibility and self-control and their difficulty to conceive

behavioral consequences, which may conclude in unstable (or criminal)

behavior.

In a 2008 study conducted by Barbosa & Monteiro, it was discovered

that the recurrent criminals that were considered in this study had

executive dysfunction.

In view of the fact that abnormalities in executive function can limit

how people respond to rehabilitation and re-socialization programs

these findings of the recurrent criminals are justified. Statistically

significant relations have been discerned between anti-social behavior

and executive function deficits.

These findings relate to the emotional instability that is connected

with executive function as a detrimental symptom that can also be linked

towards criminal behavior. Conversely, it is unclear as to the

specificity of anti-social behavior to executive function deficits as

opposed to other generalized neuropsychological deficits.

The uncontrollable deficiency of executive function has an increased

expectancy for aggressive behavior that can result in a criminal deed. Orbitofrontal injury also hinders the ability to be risk avoidant, make social judgments, and may cause reflexive aggression.

A common retort to these findings is that the higher incidence of

cerebral lesions among the criminal population may be due to the peril

associated with a life of crime.

Along with this reasoning, it would be assumed that some other

personality trait is responsible for the disregard of social

acceptability and reduction in social aptitude.

Furthermore, some think the dysfunction cannot be entirely to blame.

There are interacting environmental factors that also have an influence

on the likelihood of criminal action. This theory proposes that

individuals with this deficit are less able to control impulses or

foresee the consequences of actions that seem attractive at the time

(see above) and are also typically provoked by environmental factors.

One must recognize that the frustrations of life, combined with a

limited ability to control life events, can easily cause aggression

and/or other criminal activities.