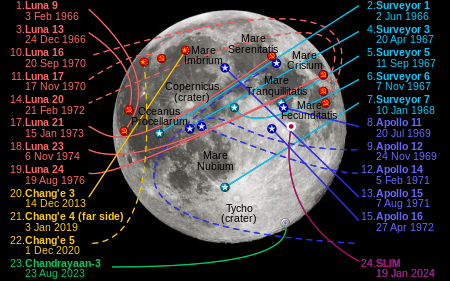

The near side of the Moon (north at top) as seen from Earth |

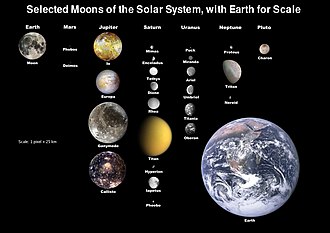

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. Its diameter is about one-quarter of Earth's (comparable to the width of Australia), making it the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet. It is larger than all known dwarf planets in the Solar System. The Moon is a planetary-mass object with a differentiated rocky body, making it a satellite planet under the geophysical definitions of the term. It lacks any significant atmosphere, hydrosphere, or magnetic field. Its surface gravity is about one-sixth of Earth's at 0.1654 g—Jupiter's moon Io is the only satellite in the Solar System known to have a higher surface gravity and density.

The Moon orbits Earth at an average distance of 384,400 km (238,900 mi), or about 30 times Earth's diameter. Its gravitational influence is the main driver of Earth's tides and very slowly lengthens Earth's day. The Moon's orbit around Earth has a sidereal period of 27.3 days. During each synodic period of 29.5 days, the amount of the Moon's Earth-facing surface that is illuminated by the Sun varies from none up to nearly 100%, resulting in lunar phases that form the basis for the months of a lunar calendar. The Moon is tidally locked to Earth, which means that the length of a full rotation of the Moon on its own axis causes its same side (the near side) to always face Earth, and the somewhat longer lunar day is the same as the synodic period. Due to cyclical shifts in perspective (libration), 59% of the lunar surface is visible from Earth.

The most widely accepted origin explanation posits that the Moon formed 4.51 billion years ago, not long after Earth's formation, out of the debris from a giant impact between Earth and a hypothesized Mars-sized body called Theia. It receded to a wider orbit because of tidal interaction with the Earth. The near side of the Moon is marked by dark volcanic maria ("seas"), which fill the spaces between bright ancient crustal highlands and prominent impact craters. Most of the large impact basins and mare surfaces were in place by the end of the Imbrian period, some three billion years ago. Although the reflectance of the lunar surface is low (comparable to that of asphalt), its large angular diameter makes the full moon the brightest celestial object in the night sky. The Moon's apparent size is nearly the same as that of the Sun, allowing it to cover the Sun almost completely during a total solar eclipse.

Both the Moon's prominence in Earth's sky and its regular cycle of phases have provided cultural references and influences for human societies throughout history. Such influences can be found in language, calendar systems, art, and mythology. The first artificial object to reach the Moon was the Soviet Union's uncrewed Luna 2 spacecraft in 1959; this was followed by the first successful soft landing by Luna 9 in 1966. The only human lunar missions to date have been those of the United States' Apollo program, which landed twelve men on the surface between 1969 and 1972. These and later uncrewed missions returned lunar rocks that have been used to develop a detailed geological understanding of the Moon's origins, internal structure, and subsequent history. The Moon is the only celestial body visited by humans.

Names and etymology

The usual English proper name for Earth's natural satellite is simply Moon, with a capital M. The noun moon is derived from Old English mōna, which (like all its Germanic cognates) stems from Proto-Germanic *mēnōn, which in turn comes from Proto-Indo-European *mēnsis "month" (from earlier *mēnōt, genitive *mēneses) which may be related to the verb "measure" (of time).

Occasionally, the name Luna /ˈluːnə/ is used in scientific writing and especially in science fiction to distinguish the Earth's moon from others, while in poetry "Luna" has been used to denote personification of the Moon. Cynthia /ˈsɪnθiə/ is another poetic name, though rare, for the Moon personified as a goddess, while Selene /səˈliːniː/ (literally "Moon") is the Greek goddess of the Moon.

The usual English adjective pertaining to the Moon is "lunar", derived from the Latin word for the Moon, lūna. The adjective selenian /səliːniən/, derived from the Greek word for the Moon, σελήνη selēnē, and used to describe the Moon as a world rather than as an object in the sky, is rare, while its cognate selenic was originally a rare synonym but now nearly always refers to the chemical element selenium. The Greek word for the Moon does however provide us with the prefix seleno-, as in selenography, the study of the physical features of the Moon, as well as the element name selenium.

The Greek goddess of the wilderness and the hunt, Artemis, equated with the Roman Diana, one of whose symbols was the Moon and who was often regarded as the goddess of the Moon, was also called Cynthia, from her legendary birthplace on Mount Cynthus. These names – Luna, Cynthia and Selene – are reflected in technical terms for lunar orbits such as apolune, pericynthion and selenocentric.

The astronomical symbol for the Moon is a crescent, ![]() , for example in M☾ 'lunar mass' (also ML).

, for example in M☾ 'lunar mass' (also ML).

Natural history

Lunar geologic timescale

The lunar geological periods are named after their characteristic features, from most impact craters outside the dark mare, to the mare and later craters, and finally the young still bright and therefore readily visible craters with ray systems like Copernicus or Tycho.

Formation

Isotope dating of lunar samples suggests the Moon formed around 50 million years after the origin of the Solar System. Historically, several formation mechanisms have been proposed, but none satisfactorily explains the features of the Earth–Moon system. A fission of the Moon from Earth's crust through centrifugal force would require too great an initial rotation rate of Earth. Gravitational capture of a pre-formed Moon depends on an unfeasibly extended atmosphere of Earth to dissipate the energy of the passing Moon. A co-formation of Earth and the Moon together in the primordial accretion disk does not explain the depletion of metals in the Moon. None of these hypotheses can account for the high angular momentum of the Earth–Moon system.

The prevailing theory is that the Earth–Moon system formed after a giant impact of a Mars-sized body (named Theia) with the proto-Earth. The impact blasted material into orbit about the Earth and the material accreted and formed the Moon just beyond the Earth's Roche limit of ~2.56 R🜨.

Giant impacts are thought to have been common in the early Solar System. Computer simulations of giant impacts have produced results that are consistent with the mass of the lunar core and the angular momentum of the Earth–Moon system. These simulations show that most of the Moon derived from the impactor, rather than the proto-Earth. However, more recent simulations suggest a larger fraction of the Moon derived from the proto-Earth. Other bodies of the inner Solar System such as Mars and Vesta have, according to meteorites from them, very different oxygen and tungsten isotopic compositions compared to Earth. However, Earth and the Moon have nearly identical isotopic compositions. The isotopic equalization of the Earth-Moon system might be explained by the post-impact mixing of the vaporized material that formed the two, although this is debated.

The impact would have released enough energy to liquefy both the ejecta and the Earth's crust, forming a magma ocean. The liquefied ejecta could have then re-accreted into the Earth–Moon system. Similarly, the newly formed Moon would have had its own lunar magma ocean; its depth is estimated from about 500 km (300 miles) to 1,737 km (1,079 miles).

While the giant-impact theory explains many lines of evidence, some questions are still unresolved, most of which involve the Moon's composition. Above a high resolution threshold for simulations, a study published in 2022 finds that giant impacts can immediately place a satellite with similar mass and iron content to the Moon into orbit far outside Earth's Roche limit. Even satellites that initially pass within the Roche limit can reliably and predictably survive, by being partially stripped and then torqued onto wider, stable orbits.

Natural development

After the Moon's formation it settled into a much closer Earth orbit than it has today. Each body therefore appeared much larger in the sky of the other, eclipses were more frequent, and tidal effects were stronger. Due to tidal acceleration, the Moon's orbit around Earth has become significantly larger, with a longer period.

Since cooling and stripped of most of its atmosphere, both originating from its initial formation, the lunar surface has been shaped by large impact events and many small ones, forming a landscape featuring craters of all ages. The prominent lunar maria were produced by volcanic activity. Volcanically active until 1.2 billion years ago, most of the Moon's mare basalts erupted during the Imbrian period, 3.3–3.7 billion years ago, though some are as young as 1.2 billion years and some as old as 4.2 billion years. There are differing explanations for the causes behind the eruption of mare basalts, particularly their uneven occurrence, mainly on the near-side. Causes of the distribution of the lunar highlands on the far side are also not well understood. One explanation suggests that large meteorites were hitting the Moon in its early history, leaving large craters which then were filled with lava. Other explanations suggest processes of lunar volcanism.

Physical characteristics

The Moon is a very slightly scalene ellipsoid due to tidal stretching, with its long axis displaced 30° from facing the Earth, due to gravitational anomalies from impact basins. Its shape is more elongated than current tidal forces can account for. This 'fossil bulge' indicates that the Moon solidified when it orbited at half its current distance to the Earth, and that it is now too cold for its shape to adjust to its orbit.

Size and mass

The Moon is by size and mass the fifth largest natural satellite of the Solar System, categorizeable as one of its planetary-mass moons, making it a satellite planet under the geophysical definitions of the term. It is smaller than Mercury and considerably larger than the largest dwarf planet of the Solar System, Pluto. While the minor-planet moon Charon of the Pluto-Charon system is larger relative to Pluto, the Moon is the largest natural satellite of the Solar System relative to their primary planets.

The Moon's diameter is about 3,500 km, more than a quarter of Earth's, with the face of the Moon comparable to the width of Australia. The whole surface area of the Moon is about 38 million square kilometers, between the size of the Americas (North and South America) and Africa.

The Moon's mass is 1/81 of Earth's, being the second densest among the planetary moons, and having the second highest surface gravity, after Io, at 0.1654 g and an escape velocity of 2.38 km/s (8600 km/h; 5300 mph).

Structure

The Moon is a differentiated body that was initially in hydrostatic equilibrium but has since departed from this condition. It has a geochemically distinct crust, mantle, and core. The Moon has a solid iron-rich inner core with a radius possibly as small as 240 kilometres (150 mi) and a fluid outer core primarily made of liquid iron with a radius of roughly 300 kilometres (190 mi). Around the core is a partially molten boundary layer with a radius of about 500 kilometres (310 mi). This structure is thought to have developed through the fractional crystallization of a global magma ocean shortly after the Moon's formation 4.5 billion years ago.

Crystallization of this magma ocean would have created a mafic mantle from the precipitation and sinking of the minerals olivine, clinopyroxene, and orthopyroxene; after about three-quarters of the magma ocean had crystallized, lower-density plagioclase minerals could form and float into a crust atop. The final liquids to crystallize would have been initially sandwiched between the crust and mantle, with a high abundance of incompatible and heat-producing elements. Consistent with this perspective, geochemical mapping made from orbit suggests a crust of mostly anorthosite. The Moon rock samples of the flood lavas that erupted onto the surface from partial melting in the mantle confirm the mafic mantle composition, which is more iron-rich than that of Earth. The crust is on average about 50 kilometres (31 mi) thick.

The Moon is the second-densest satellite in the Solar System, after Io. However, the inner core of the Moon is small, with a radius of about 350 kilometres (220 mi) or less, around 20% of the radius of the Moon. Its composition is not well understood, but is probably metallic iron alloyed with a small amount of sulfur and nickel; analyses of the Moon's time-variable rotation suggest that it is at least partly molten. The pressure at the lunar core is estimated to be 5 GPa (49,000 atm).

Gravitational field

On average the Moon's surface gravity is 1.62 m/s2 (0.1654 g; 5.318 ft/s2), about half of the surface gravity of Mars and about a sixth of Earth's.

The Moon's gravitational field is not uniform. The details of the gravitational field have been measured through tracking the Doppler shift of radio signals emitted by orbiting spacecraft. The main lunar gravity features are mascons, large positive gravitational anomalies associated with some of the giant impact basins, partly caused by the dense mare basaltic lava flows that fill those basins. The anomalies greatly influence the orbit of spacecraft about the Moon. There are some puzzles: lava flows by themselves cannot explain all of the gravitational signature, and some mascons exist that are not linked to mare volcanism.

Magnetic field

The Moon has an external magnetic field of less than 0.2 nanoteslas, or less than one hundred thousandth that of Earth. The Moon does not currently have a global dipolar magnetic field and only has crustal magnetization likely acquired early in its history when a dynamo was still operating. However, early in its history, 4 billion years ago, its magnetic field strength was likely close to that of Earth today. This early dynamo field apparently expired by about one billion years ago, after the lunar core had completely crystallized. Theoretically, some of the remnant magnetization may originate from transient magnetic fields generated during large impacts through the expansion of plasma clouds. These clouds are generated during large impacts in an ambient magnetic field. This is supported by the location of the largest crustal magnetizations situated near the antipodes of the giant impact basins.

Atmosphere

The Moon has an atmosphere so tenuous as to be nearly vacuum, with a total mass of less than 10 tonnes (9.8 long tons; 11 short tons). The surface pressure of this small mass is around 3 × 10−15 atm (0.3 nPa); it varies with the lunar day. Its sources include outgassing and sputtering, a product of the bombardment of lunar soil by solar wind ions. Elements that have been detected include sodium and potassium, produced by sputtering (also found in the atmospheres of Mercury and Io); helium-4 and neon from the solar wind; and argon-40, radon-222, and polonium-210, outgassed after their creation by radioactive decay within the crust and mantle. The absence of such neutral species (atoms or molecules) as oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, hydrogen and magnesium, which are present in the regolith, is not understood. Water vapor has been detected by Chandrayaan-1 and found to vary with latitude, with a maximum at ~60–70 degrees; it is possibly generated from the sublimation of water ice in the regolith. These gases either return into the regolith because of the Moon's gravity or are lost to space, either through solar radiation pressure or, if they are ionized, by being swept away by the solar wind's magnetic field.

Studies of Moon magma samples retrieved by the Apollo missions demonstrate that the Moon had once possessed a relatively thick atmosphere for a period of 70 million years between 3 and 4 billion years ago. This atmosphere, sourced from gases ejected from lunar volcanic eruptions, was twice the thickness of that of present-day Mars. The ancient lunar atmosphere was eventually stripped away by solar winds and dissipated into space.

A permanent Moon dust cloud exists around the Moon, generated by small particles from comets. Estimates are 5 tons of comet particles strike the Moon's surface every 24 hours, resulting in the ejection of dust particles. The dust stays above the Moon approximately 10 minutes, taking 5 minutes to rise, and 5 minutes to fall. On average, 120 kilograms of dust are present above the Moon, rising up to 100 kilometers above the surface. Dust counts made by LADEE's Lunar Dust EXperiment (LDEX) found particle counts peaked during the Geminid, Quadrantid, Northern Taurid, and Omicron Centaurid meteor showers, when the Earth, and Moon pass through comet debris. The lunar dust cloud is asymmetric, being more dense near the boundary between the Moon's dayside and nightside.

Surface conditions

Ionizing radiation from cosmic rays, the Sun and the resulting neutron radiation produce radiation levels on average of 1.369 millisieverts per day during lunar daytime, which is about 2.6 times more than on the International Space Station with 0.53 millisieverts per day at about 400 km above Earth in orbit, 5-10 times more than during a trans-Atlantic flight, 200 times more than on Earth's surface. For further comparison radiation on a flight to Mars is about 1.84 millisieverts per day and on Mars on average 0.64 millisieverts per day, with some locations on Mars possibly having levels as low as 0.342 millisieverts per day.

The Moon's axial tilt with respect to the ecliptic is only 1.5427°, much less than the 23.44° of Earth. Because of this small tilt, the Moon's solar illumination varies much less with season than on Earth and it allows for the existence of some peaks of eternal light at the Moon's north pole, at the rim of the crater Peary.

The surface is exposed to drastic temperature differences ranging from 140 °C to −171 °C depending on the solar irradiance. Because of the lack of atmosphere, temperatures of different areas vary particularly upon whether they are in sunlight or shadow, making topographical details play a decisive role on local surface temperatures. Parts of many craters, particularly the bottoms of many polar craters, are permanently shadowed, these "craters of eternal darkness" have extremely low temperatures. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter measured the lowest summer temperatures in craters at the southern pole at 35 K (−238 °C; −397 °F) and just 26 K (−247 °C; −413 °F) close to the winter solstice in the north polar crater Hermite. This is the coldest temperature in the Solar System ever measured by a spacecraft, colder even than the surface of Pluto.

Blanketed on top of the Moon's crust is a highly comminuted (broken into ever smaller particles) and impact gardened mostly gray surface layer called regolith, formed by impact processes. The finer regolith, the lunar soil of silicon dioxide glass, has a texture resembling snow and a scent resembling spent gunpowder. The regolith of older surfaces is generally thicker than for younger surfaces: it varies in thickness from 10–15 m (33–49 ft) in the highlands and 4–5 m (13–16 ft) in the maria. Beneath the finely comminuted regolith layer is the megaregolith, a layer of highly fractured bedrock many kilometers thick.

These extreme conditions for example are considered to make it unlikely for spacecraft to harbor bacterial spores at the Moon longer than just one lunar orbit.

Surface features

The topography of the Moon has been measured with laser altimetry and stereo image analysis. Its most extensive topographic feature is the giant far-side South Pole–Aitken basin, some 2,240 km (1,390 mi) in diameter, the largest crater on the Moon and the second-largest confirmed impact crater in the Solar System. At 13 km (8.1 mi) deep, its floor is the lowest point on the surface of the Moon. The highest elevations of the Moon's surface are located directly to the northeast, which might have been thickened by the oblique formation impact of the South Pole–Aitken basin. Other large impact basins such as Imbrium, Serenitatis, Crisium, Smythii, and Orientale possess regionally low elevations and elevated rims. The far side of the lunar surface is on average about 1.9 km (1.2 mi) higher than that of the near side.

The discovery of fault scarp cliffs suggest that the Moon has shrunk by about 90 metres (300 ft) within the past billion years. Similar shrinkage features exist on Mercury. Mare Frigoris, a basin near the north pole long assumed to be geologically dead, has cracked and shifted. Since the Moon doesn't have tectonic plates, its tectonic activity is slow and cracks develop as it loses heat.

Volcanic features

The main features visible from Earth by the naked eye are dark and relatively featureless lunar plains called maria (singular mare; Latin for "seas", as they were once believed to be filled with water) are vast solidified pools of ancient basaltic lava. Although similar to terrestrial basalts, lunar basalts have more iron and no minerals altered by water. The majority of these lava deposits erupted or flowed into the depressions associated with impact basins. Several geologic provinces containing shield volcanoes and volcanic domes are found within the near side "maria".

Almost all maria are on the near side of the Moon, and cover 31% of the surface of the near side compared with 2% of the far side. This is likely due to a concentration of heat-producing elements under the crust on the near side, which would have caused the underlying mantle to heat up, partially melt, rise to the surface and erupt. Most of the Moon's mare basalts erupted during the Imbrian period, 3.3–3.7 billion years ago, though some being as young as 1.2 billion years and as old as 4.2 billion years.

In 2006, a study of Ina, a tiny depression in Lacus Felicitatis, found jagged, relatively dust-free features that, because of the lack of erosion by infalling debris, appeared to be only 2 million years old. Moonquakes and releases of gas indicate continued lunar activity. Evidence of recent lunar volcanism has been identified at 70 irregular mare patches, some less than 50 million years old. This raises the possibility of a much warmer lunar mantle than previously believed, at least on the near side where the deep crust is substantially warmer because of the greater concentration of radioactive elements. Evidence has been found for 2–10 million years old basaltic volcanism within the crater Lowell, inside the Orientale basin. Some combination of an initially hotter mantle and local enrichment of heat-producing elements in the mantle could be responsible for prolonged activities on the far side in the Orientale basin.

The lighter-colored regions of the Moon are called terrae, or more commonly highlands, because they are higher than most maria. They have been radiometrically dated to having formed 4.4 billion years ago, and may represent plagioclase cumulates of the lunar magma ocean. In contrast to Earth, no major lunar mountains are believed to have formed as a result of tectonic events.

The concentration of maria on the near side likely reflects the substantially thicker crust of the highlands of the Far Side, which may have formed in a slow-velocity impact of a second moon of Earth a few tens of millions of years after the Moon's formation. Alternatively, it may be a consequence of asymmetrical tidal heating when the Moon was much closer to the Earth.

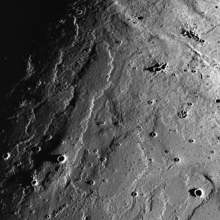

Impact craters

A major geologic process that has affected the Moon's surface is impact cratering, with craters formed when asteroids and comets collide with the lunar surface. There are estimated to be roughly 300,000 craters wider than 1 km (0.6 mi) on the Moon's near side. The lunar geologic timescale is based on the most prominent impact events, including Nectaris, Imbrium, and Orientale; structures characterized by multiple rings of uplifted material, between hundreds and thousands of kilometers in diameter and associated with a broad apron of ejecta deposits that form a regional stratigraphic horizon. The lack of an atmosphere, weather, and recent geological processes mean that many of these craters are well-preserved. Although only a few multi-ring basins have been definitively dated, they are useful for assigning relative ages. Because impact craters accumulate at a nearly constant rate, counting the number of craters per unit area can be used to estimate the age of the surface. The radiometric ages of impact-melted rocks collected during the Apollo missions cluster between 3.8 and 4.1 billion years old: this has been used to propose a Late Heavy Bombardment period of increased impacts.

High-resolution images from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in the 2010s show a contemporary crater-production rate significantly higher than was previously estimated. A secondary cratering process caused by distal ejecta is thought to churn the top two centimeters of regolith on a timescale of 81,000 years. This rate is 100 times faster than the rate computed from models based solely on direct micrometeorite impacts.

Lunar swirls

Lunar swirls are enigmatic features found across the Moon's surface. They are characterized by a high albedo, appear optically immature (i.e. the optical characteristics of a relatively young regolith), and often have a sinuous shape. Their shape is often accentuated by low albedo regions that wind between the bright swirls. They are located in places with enhanced surface magnetic fields and many are located at the antipodal point of major impacts. Well known swirls include the Reiner Gamma feature and Mare Ingenii. They are hypothesized to be areas that have been partially shielded from the solar wind, resulting in slower space weathering.

Presence of water

Liquid water cannot persist on the lunar surface. When exposed to solar radiation, water quickly decomposes through a process known as photodissociation and is lost to space. However, since the 1960s, scientists have hypothesized that water ice may be deposited by impacting comets or possibly produced by the reaction of oxygen-rich lunar rocks, and hydrogen from solar wind, leaving traces of water which could possibly persist in cold, permanently shadowed craters at either pole on the Moon. Computer simulations suggest that up to 14,000 km2 (5,400 sq mi) of the surface may be in permanent shadow. The presence of usable quantities of water on the Moon is an important factor in rendering lunar habitation as a cost-effective plan; the alternative of transporting water from Earth would be prohibitively expensive.

In years since, signatures of water have been found to exist on the lunar surface. In 1994, the bistatic radar experiment located on the Clementine spacecraft, indicated the existence of small, frozen pockets of water close to the surface. However, later radar observations by Arecibo, suggest these findings may rather be rocks ejected from young impact craters. In 1998, the neutron spectrometer on the Lunar Prospector spacecraft showed that high concentrations of hydrogen are present in the first meter of depth in the regolith near the polar regions. Volcanic lava beads, brought back to Earth aboard Apollo 15, showed small amounts of water in their interior.

The 2008 Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft has since confirmed the existence of surface water ice, using the on-board Moon Mineralogy Mapper. The spectrometer observed absorption lines common to hydroxyl, in reflected sunlight, providing evidence of large quantities of water ice, on the lunar surface. The spacecraft showed that concentrations may possibly be as high as 1,000 ppm. Using the mapper's reflectance spectra, indirect lighting of areas in shadow confirmed water ice within 20° latitude of both poles in 2018. In 2009, LCROSS sent a 2,300 kg (5,100 lb) impactor into a permanently shadowed polar crater, and detected at least 100 kg (220 lb) of water in a plume of ejected material. Another examination of the LCROSS data showed the amount of detected water to be closer to 155 ± 12 kg (342 ± 26 lb).

In May 2011, 615–1410 ppm water in melt inclusions in lunar sample 74220 was reported, the famous high-titanium "orange glass soil" of volcanic origin collected during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. The inclusions were formed during explosive eruptions on the Moon approximately 3.7 billion years ago. This concentration is comparable with that of magma in Earth's upper mantle. Although of considerable selenological interest, this insight does not mean that water is easily available since the sample originated many kilometers below the surface, and the inclusions are so difficult to access that it took 39 years to find them with a state-of-the-art ion microprobe instrument.

Analysis of the findings of the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) revealed in August 2018 for the first time "definitive evidence" for water-ice on the lunar surface. The data revealed the distinct reflective signatures of water-ice, as opposed to dust and other reflective substances. The ice deposits were found on the North and South poles, although it is more abundant in the South, where water is trapped in permanently shadowed craters and crevices, allowing it to persist as ice on the surface since they are shielded from the sun.

In October 2020, astronomers reported detecting molecular water on the sunlit surface of the Moon by several independent spacecraft, including the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).

Earth–Moon system

Orbit

The Earth and the Moon form the Earth-Moon satellite system with a shared center of mass, or barycenter. This barycenter is 1,700 km (1,100 mi) (about a quarter of Earth's radius) beneath the Earth's surface.

The Moon's orbit is slightly elliptical, with an orbital eccentricity of 0.055. The semi-major axis of the geocentric lunar orbit, called the Lunar distance, is approximately 400,000 km (250,000 miles or 1.28 light-seconds).

The Moon makes a complete orbit around Earth with respect to the fixed stars, its sidereal period, about once every 27.3 days. However, because the Earth-Moon system moves at the same time in its orbit around the Sun, it takes slightly longer, 29.5 days, to return at the same lunar phase, completing a full cycle, as seen from Earth. This synodic period or synodic month is commonly known as the lunar month and is equal to the length of the solar day on the Moon.

Due to tidal locking, the Moon has a 1:1 spin–orbit resonance. This rotation–orbit ratio makes the Moon's orbital periods around Earth equal to its corresponding rotation periods. This is the reason for only one side of the Moon, its so-called near side, being visible from Earth. That said, while the movement of the Moon is in resonance, it still is not without nuances such as libration, resulting in slightly changing perspectives, making over time and location on Earth about 59% of the Moon's surface visible from Earth.

Unlike most satellites of other planets, the Moon's orbital plane is closer to the ecliptic plane than to the planet's equatorial plane. The Moon's orbit is subtly perturbed by the Sun and Earth in many small, complex and interacting ways. For example, the plane of the Moon's orbit gradually rotates once every 18.61 years, which affects other aspects of lunar motion. These follow-on effects are mathematically described by Cassini's laws.

Tidal effects

The gravitational attraction that Earth and the Moon (as well as the Sun) exert on each other manifests in a slightly greater attraction on the sides of closest to each other, resulting in tidal forces. Ocean tides are the most widely experienced result of this, but tidal forces considerably affect also other mechanics of Earth, as well as the Moon and their system.

The lunar solid crust experiences tides of around 10 cm (4 in) amplitude over 27 days, with three components: a fixed one due to Earth, because they are in synchronous rotation, a variable tide due to orbital eccentricity and inclination, and a small varying component from the Sun. The Earth-induced variable component arises from changing distance and libration, a result of the Moon's orbital eccentricity and inclination (if the Moon's orbit were perfectly circular and un-inclined, there would only be solar tides). According to recent research, scientists suggest that the Moon's influence on the Earth may contribute to maintaining Earth's magnetic field.

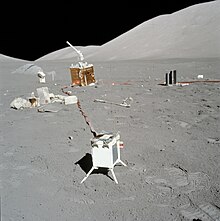

The cumulative effects of stress built up by these tidal forces produces moonquakes. Moonquakes are much less common and weaker than are earthquakes, although moonquakes can last for up to an hour – significantly longer than terrestrial quakes – because of scattering of the seismic vibrations in the dry fragmented upper crust. The existence of moonquakes was an unexpected discovery from seismometers placed on the Moon by Apollo astronauts from 1969 through 1972.

The most commonly known effect of tidal forces are elevated sea levels called ocean tides. While the Moon exerts most of the tidal forces, the Sun also exerts tidal forces and therefore contributes to the tides as much as 40% of the Moon's tidal force; producing in interplay the spring and neap tides.

The tides are two bulges in the Earth's oceans, one on the side facing the Moon and the other on the side opposite. As the Earth rotates on its axis, one of the ocean bulges (high tide) is held in place "under" the Moon, while another such tide is opposite. As a result, there are two high tides, and two low tides in about 24 hours. Since the Moon is orbiting the Earth in the same direction of the Earth's rotation, the high tides occur about every 12 hours and 25 minutes; the 25 minutes is due to the Moon's time to orbit the Earth.

If the Earth were a water world (one with no continents) it would produce a tide of only one meter, and that tide would be very predictable, but the ocean tides are greatly modified by other effects:

- the frictional coupling of water to Earth's rotation through the ocean floors

- the inertia of water's movement

- ocean basins that grow shallower near land

- the sloshing of water between different ocean basins

As a result, the timing of the tides at most points on the Earth is a product of observations that are explained, incidentally, by theory.

Delays in the tidal peaks of both ocean and solid-body tides cause torque in opposition to the Earth's rotation. This "drains" angular momentum and rotational kinetic energy from Earth's rotation, slowing the Earth's rotation. That angular momentum, lost from the Earth, is transferred to the Moon in a process known as tidal acceleration, which lifts the Moon into a higher orbit while lowering orbital speed around the Earth.

Thus the distance between Earth and Moon is increasing, and the Earth's rotation is slowing in reaction. Measurements from laser reflectors left during the Apollo missions (lunar ranging experiments) have found that the Moon's distance increases by 38 mm (1.5 in) per year (roughly the rate at which human fingernails grow). Atomic clocks show that Earth's day lengthens by about 17 microseconds every year, slowly increasing the rate at which UTC is adjusted by leap seconds.

This tidal drag makes the rotation of the Earth and the orbital period of the Moon very slowly match. This matching first results in tidally locking the lighter body of the orbital system, as is already the case with the Moon. Theoretically, in 50 billion years, the Earth's rotation will have slowed to the point of matching the Moon's orbital period, causing the Earth to always present the same side to the Moon. However, the Sun will become a red giant, engulfing the Earth-Moon system, long before then.

Position and appearance

The Moon's highest altitude at culmination varies by its lunar phase, or more correctly its orbital position, and time of the year, or more correctly the position of the Earth's axis. The full moon is highest in the sky during winter and lowest during summer (for each hemisphere respectively), with its altitude changing towards dark moon to the opposite.

At the North and South Poles the Moon is 24 hours above the horizon for two weeks every tropical month (about 27.3 days), comparable to the polar day of the tropical year. Zooplankton in the Arctic use moonlight when the Sun is below the horizon for months on end.

The apparent orientation of the Moon depends on its position in the sky and the hemisphere of the Earth from which it is being viewed. In the northern hemisphere it appears upside down compared to the view from the southern hemisphere. Sometimes the "horns" of a crescent moon appear to be pointing more upwards than sideways. This phenomenon is called a wet moon and occurs more frequently in the tropics.

The distance between the Moon and Earth varies from around 356,400 km (221,500 mi) (perigee) to 406,700 km (252,700 mi) (apogee), making the Moon's apparent size fluctuate. On average the Moon's angular diameter is about 0.52°, roughly the same apparent size as the Sun (see § Eclipses). In addition, a purely psychological effect, known as the Moon illusion, makes the Moon appear larger when close to the horizon.

Despite the Moon's tidal locking, the effect of libration makes about 59% of the Moon's surface visible from Earth over the course of one month.

Rotation

The tidally locked synchronous rotation of the Moon as it orbits the Earth results in it always keeping nearly the same face turned towards the planet. The side of the Moon that faces Earth is called the near side, and the opposite the far side. The far side is often inaccurately called the "dark side", but it is in fact illuminated as often as the near side: once every 29.5 Earth days. During dark moon to new moon, the near side is dark.

The Moon originally rotated at a faster rate, but early in its history its rotation slowed and became tidally locked in this orientation as a result of frictional effects associated with tidal deformations caused by Earth. With time, the energy of rotation of the Moon on its axis was dissipated as heat, until there was no rotation of the Moon relative to Earth. In 2016, planetary scientists using data collected on the 1998-99 NASA Lunar Prospector mission, found two hydrogen-rich areas (most likely former water ice) on opposite sides of the Moon. It is speculated that these patches were the poles of the Moon billions of years ago before it was tidally locked to Earth.

Illumination and phases

Half of the Moon's surface is always illuminated by the Sun (except during a lunar eclipse). Earth also reflects light onto the Moon, observable at times as Earthlight when it is again reflected back to Earth from areas of the near side of the Moon that are not illuminated by the Sun.

With the different positions of the Moon, different areas of it are illuminated by the Sun. This illumination of different lunar areas, as viewed from Earth, produces the different lunar phases during the synodic month. A phase is equal to the area of the visible lunar sphere that is illuminated by the Sun. This area or degree of illumination is given by , where is the elongation (i.e., the angle between Moon, the observer on Earth, and the Sun).

On 14 November 2016, the Moon was at full phase closer to Earth than it had been since 1948. It was 14% closer and larger than its farthest position in apogee. This closest point coincided within an hour of a full moon, and it was 30% more luminous than when at its greatest distance because of its increased apparent diameter, which made it a particularly notable example of a "supermoon".

At lower levels, the human perception of reduced brightness as a percentage is provided by the following formula:

When the actual reduction is 1.00 / 1.30, or about 0.770, the perceived reduction is about 0.877, or 1.00 / 1.14. This gives a maximum perceived increase of 14% between apogee and perigee moons of the same phase.

There has been historical controversy over whether observed features on the Moon's surface change over time. Today, many of these claims are thought to be illusory, resulting from observation under different lighting conditions, poor astronomical seeing, or inadequate drawings. However, outgassing does occasionally occur and could be responsible for a minor percentage of the reported lunar transient phenomena. Recently, it has been suggested that a roughly 3 km (1.9 mi) diameter region of the lunar surface was modified by a gas release event about a million years ago.

Albedo and color

The Moon has an exceptionally low albedo, giving it a reflectance that is slightly brighter than that of worn asphalt. Despite this, it is the brightest object in the sky after the Sun. This is due partly to the brightness enhancement of the opposition surge; the Moon at quarter phase is only one-tenth as bright, rather than half as bright, as at full moon. Additionally, color constancy in the visual system recalibrates the relations between the colors of an object and its surroundings, and because the surrounding sky is comparatively dark, the sunlit Moon is perceived as a bright object. The edges of the full moon seem as bright as the center, without limb darkening, because of the reflective properties of lunar soil, which retroreflects light more towards the Sun than in other directions. The Moon's color depends on the light the Moon reflects, which in turn depends on the Moon's surface and its features, having for example large darker regions. In general the lunar surface reflects a brown-tinged gray light.

Viewed from Earth the air filters the reflected light, at times giving it a red color depending on the angle of the Moon in the sky and thickness of the atmosphere, or a blue tinge depending on the particles in the air, as in cases of volcanic particles. The terms blood moon and blue moon do not necessarily refer to circumstances of red or blue moonlight, but are rather particular cultural references such as particular full moons of a year.

Eclipses

Eclipses only occur when the Sun, Earth, and Moon are all in a straight line (termed "syzygy"). Solar eclipses occur at new moon, when the Moon is between the Sun and Earth. In contrast, lunar eclipses occur at full moon, when Earth is between the Sun and Moon. The apparent size of the Moon is roughly the same as that of the Sun, with both being viewed at close to one-half a degree wide. The Sun is much larger than the Moon but it is the vastly greater distance that gives it the same apparent size as the much closer and much smaller Moon from the perspective of Earth. The variations in apparent size, due to the non-circular orbits, are nearly the same as well, though occurring in different cycles. This makes possible both total (with the Moon appearing larger than the Sun) and annular (with the Moon appearing smaller than the Sun) solar eclipses. In a total eclipse, the Moon completely covers the disc of the Sun and the solar corona becomes visible to the naked eye. Because the distance between the Moon and Earth is very slowly increasing over time, the angular diameter of the Moon is decreasing. As it evolves toward becoming a red giant, the size of the Sun, and its apparent diameter in the sky, are slowly increasing. The combination of these two changes means that hundreds of millions of years ago, the Moon would always completely cover the Sun on solar eclipses, and no annular eclipses were possible. Likewise, hundreds of millions of years in the future, the Moon will no longer cover the Sun completely, and total solar eclipses will not occur.

Because the Moon's orbit around Earth is inclined by about 5.145° (5° 9') to the orbit of Earth around the Sun, eclipses do not occur at every full and new moon. For an eclipse to occur, the Moon must be near the intersection of the two orbital planes. The periodicity and recurrence of eclipses of the Sun by the Moon, and of the Moon by Earth, is described by the saros, which has a period of approximately 18 years.

Because the Moon continuously blocks the view of a half-degree-wide circular area of the sky, the related phenomenon of occultation occurs when a bright star or planet passes behind the Moon and is occulted: hidden from view. In this way, a solar eclipse is an occultation of the Sun. Because the Moon is comparatively close to Earth, occultations of individual stars are not visible everywhere on the planet, nor at the same time. Because of the precession of the lunar orbit, each year different stars are occulted.

History of exploration and human presence

Pre-telescopic observation (before 1609)

It is believed by some that 20–30,000 year old tally sticks were used to observe the phases of the Moon, keeping time using the waxing and waning of the Moon's phases. One of the earliest-discovered possible depictions of the Moon is a 5000-year-old rock carving Orthostat 47 at Knowth, Ireland.

The ancient Greek philosopher Anaxagoras (d. 428 BC) reasoned that the Sun and Moon were both giant spherical rocks, and that the latter reflected the light of the former. Elsewhere in the 5th century BC to 4th century BC, Babylonian astronomers had recorded the 18-year Saros cycle of lunar eclipses, and Indian astronomers had described the Moon's monthly elongation. The Chinese astronomer Shi Shen (fl. 4th century BC) gave instructions for predicting solar and lunar eclipses.

In Aristotle's (384–322 BC) description of the universe, the Moon marked the boundary between the spheres of the mutable elements (earth, water, air and fire), and the imperishable stars of aether, an influential philosophy that would dominate for centuries. Archimedes (287–212 BC) designed a planetarium that could calculate the motions of the Moon and other objects in the Solar System. In the 2nd century BC, Seleucus of Seleucia correctly theorized that tides were due to the attraction of the Moon, and that their height depends on the Moon's position relative to the Sun. In the same century, Aristarchus computed the size and distance of the Moon from Earth, obtaining a value of about twenty times the radius of Earth for the distance.

Although the Chinese of the Han Dynasty believed the Moon to be energy equated to qi, their 'radiating influence' theory recognized that the light of the Moon was merely a reflection of the Sun, and Jing Fang (78–37 BC) noted the sphericity of the Moon. Ptolemy (90–168 AD) greatly improved on the numbers of Aristarchus, calculating a mean distance of 59 times Earth's radius and a diameter of 0.292 Earth diameters, close to the correct values of about 60 and 0.273 respectively. In the 2nd century AD, Lucian wrote the novel A True Story, in which the heroes travel to the Moon and meet its inhabitants. In 499 AD, the Indian astronomer Aryabhata mentioned in his Aryabhatiya that reflected sunlight is the cause of the shining of the Moon. The astronomer and physicist Alhazen (965–1039) found that sunlight was not reflected from the Moon like a mirror, but that light was emitted from every part of the Moon's sunlit surface in all directions. Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the Song dynasty created an allegory equating the waxing and waning of the Moon to a round ball of reflective silver that, when doused with white powder and viewed from the side, would appear to be a crescent.

During the Middle Ages, before the invention of the telescope, the Moon was increasingly recognised as a sphere, though many believed that it was "perfectly smooth".

Telescopic exploration (1609-1959)

In 1609, Galileo Galilei used an early telescope to make drawings of the Moon for his book Sidereus Nuncius, and deduced that it was not smooth but had mountains and craters. Thomas Harriot had made, but not published such drawings a few months earlier.

Telescopic mapping of the Moon followed: later in the 17th century, the efforts of Giovanni Battista Riccioli and Francesco Maria Grimaldi led to the system of naming of lunar features in use today. The more exact 1834–1836 Mappa Selenographica of Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich Mädler, and their associated 1837 book Der Mond, the first trigonometrically accurate study of lunar features, included the heights of more than a thousand mountains, and introduced the study of the Moon at accuracies possible in earthly geography. Lunar craters, first noted by Galileo, were thought to be volcanic until the 1870s proposal of Richard Proctor that they were formed by collisions. This view gained support in 1892 from the experimentation of geologist Grove Karl Gilbert, and from comparative studies from 1920 to the 1940s, leading to the development of lunar stratigraphy, which by the 1950s was becoming a new and growing branch of astrogeology.

First missions to the Moon (1959–1990)

After World War II the first launch systems were developed and by the end of the 1950s they reached capabilities that allowed the Soviet Union and the United States to launch spacecrafts into space. The Cold War fueled a closely followed development of launch systems by the two states, resulting in the so-called Space Race and its later phase the Moon Race, accelerating efforts and interest in exploration of the Moon.

After the first spaceflight of Sputnik 1 in 1957 during International Geophysical Year the spacecrafts of the Soviet Union's Luna program were the first to accomplish a number of goals. Following three unnamed failed missions in 1958, the first human-made object Luna 1 escaped Earth's gravity and passed near the Moon in 1959. Later that year the first human-made object Luna 2 reached the Moon's surface by intentionally impacting. By the end of the year Luna 3 reached as the first human-made object the normally occluded far side of the Moon, taking the first photographs of it. The first spacecraft to perform a successful lunar soft landing was Luna 9 and the first vehicle to orbit the Moon was Luna 10, both in 1966.

Following President John F. Kennedy's 1961 commitment to a crewed Moon landing before the end of the decade, the United States, under NASA leadership, launched a series of uncrewed probes to develop an understanding of the lunar surface in preparation for human missions: the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Ranger program, the Lunar Orbiter program and the Surveyor program. The crewed Apollo program was developed in parallel; after a series of uncrewed and crewed tests of the Apollo spacecraft in Earth orbit, and spurred on by a potential Soviet lunar human landing, in 1968 Apollo 8 made the first human mission to lunar orbit. The subsequent landing of the first humans on the Moon in 1969 is seen by many as the culmination of the Space Race.

Neil Armstrong became the first person to walk on the Moon as the commander of the American mission Apollo 11 by first setting foot on the Moon at 02:56 UTC on 21 July 1969. An estimated 500 million people worldwide watched the transmission by the Apollo TV camera, the largest television audience for a live broadcast at that time. The Apollo missions 11 to 17 (except Apollo 13, which aborted its planned lunar landing) removed 380.05 kilograms (837.87 lb) of lunar rock and soil in 2,196 separate samples.

Scientific instrument packages were installed on the lunar surface during all the Apollo landings. Long-lived instrument stations, including heat flow probes, seismometers, and magnetometers, were installed at the Apollo 12, 14, 15, 16, and 17 landing sites. Direct transmission of data to Earth concluded in late 1977 because of budgetary considerations, but as the stations' lunar laser ranging corner-cube retroreflector arrays are passive instruments, they are still being used. Apollo 17 in 1972 remains the last crewed mission to the Moon. Explorer 49 in 1973 was the last dedicated U.S. probe to the Moon until the 1990s.

The Soviet Union continued sending robotic missions to the Moon until 1976, deploying in 1970 with Luna 17 the first remote controlled rover Lunokhod 1 on an extraterrestrial surface, and collecting and returning 0.3 kg of rock and soil samples with three Luna sample return missions (Luna 16 in 1970, Luna 20 in 1972, and Luna 24 in 1976).

Moon Treaty and explorational absence (1976–1990)

A near lunar quietude of fourteen years followed the last Soviet mission to the Moon of 1976. Astronautics had shifted its focus towards the exploration of the inner (e.g. Venera program) and outer (e.g. Pioneer 10, 1972) Solar System planets, but also towards Earth orbit, developing and continuously operating, beside communication satellites, Earth observation satellites (e.g. Landsat program, 1972), space telescopes and particularly space stations (e.g. Salyut program, 1971).

The until 1979 negotiated Moon treaty, with its ratification in 1984 by its few signatories was about the only major activity regarding the Moon until 1990.

Renewed exploration (1990-present)

In 1990 Hiten-Hagoromo, the first dedicated lunar mission since 1976, reached the Moon. Sent by Japan, it became the first mission that was not a Soviet Union or U.S. mission to the Moon.

In 1994, the U.S. dedicated a mission to fly a spacecraft (Clementine) to the Moon again for the first time since 1973. This mission obtained the first near-global topographic map of the Moon, and the first global multispectral images of the lunar surface. In 1998, this was followed by the Lunar Prospector mission, whose instruments indicated the presence of excess hydrogen at the lunar poles, which is likely to have been caused by the presence of water ice in the upper few meters of the regolith within permanently shadowed craters.

The next years saw a row of first missions to the Moon by a new group of states actively exploring the Moon. Between 2004 and 2006 the first spacecraft by the European Space Agency (ESA) (SMART-1) reached the Moon, recording the first detailed survey of chemical elements on the lunar surface. The Chinese Lunar Exploration Program began with Chang'e 1 between 2007 and 2009, obtaining a full image map of the Moon. India reached the Moon in 2008 for the first time with its Chandrayaan-1, creating a high-resolution chemical, mineralogical and photo-geological map of the lunar surface, and confirming the presence of water molecules in lunar soil.

The U.S. launched the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and the LCROSS impactor on 18 June 2009. LCROSS completed its mission by making a planned and widely observed impact in the crater Cabeus on 9 October 2009, whereas LRO is currently in operation, obtaining precise lunar altimetry and high-resolution imagery.

China continued its lunar program in 2010 with Chang'e 2, mapping the surface at a higher resolution over an eight-month period, and in 2013 with Chang'e 3, a lunar lander along with a lunar rover named Yutu (Chinese: 玉兔; lit. 'Jade Rabbit'). This was the first lunar rover mission since Lunokhod 2 in 1973 and the first lunar soft landing since Luna 24 in 1976.

In 2014 the first privately funded probe, the Manfred Memorial Moon Mission, reached the Moon.

Another Chinese rover mission, Chang'e 4, achieved the first landing on the Moon's far side in early 2019.

Also in 2019, India successfully sent its second probe, Chandrayaan-2 to the Moon.

In 2020, China carried out its first robotic sample return mission (Chang'e 5), bringing back 1,731 grams of lunar material to Earth.

With the signing of the U.S.-led Artemis Accords in 2020, the Artemis program aims to return the astronauts to the Moon in the 2020s. The Accords have been joined by a growing number of countries. The introduction of the Artemis Accords has fueled a renewed discussion about the international framework and cooperation of lunar activity, building on the Moon Treaty and the ESA-led Moon Village concept. The U.S. developed plans for returning to the Moon beginning in 2004, which resulted in several programs. The Artemis program has advanced the farthest, and includes plans to send the first woman to the Moon as well as build an international lunar space station called Lunar Gateway.

Future

Upcoming lunar missions include the Artemis program missions and Russia's first lunar mission, Luna-Glob: an uncrewed lander with a set of seismometers, and an orbiter based on its failed Martian Fobos-Grunt mission.

In 2021, China announced a plan with Russia to develop and construct an International Lunar Research Station in the 2030s.

Human presence

Humans last landed on the Moon during the Apollo Program, a series of crewed exploration missions carried out from 1969 to 1972. Lunar orbit has seen uninterrupted presence of orbiters since 2006, performing mainly lunar observation and providing relayed communication for robotic missions on the lunar surface.

Lunar orbits and orbits around Earth–Moon Lagrange points are used to establish a near-lunar infrastructure to enable increasing human activity in cislunar space as well as on the Moon's surface. Missions at the far side of the Moon or the lunar north and south polar regions need spacecraft with special orbits, such as the Queqiao relay satellite or the planned first extraterrestrial space station, the Lunar Gateway.

Human impact

While the Moon has the lowest planetary protection target-categorization, its degradation as a pristine body and scientific place has been discussed. If there is astronomy performed from the Moon, it will need to be free from any physical and radio pollution. While the Moon has no significant atmosphere, traffic and impacts on the Moon causes clouds of dust that can spread far and possibly contaminate the original state of the Moon and its special scientific content. Scholar Alice Gorman asserts that, although the Moon is inhospitable, it is not dead, and that sustainable human activity would require treating the Moon's ecology as a co-participant.

The so-called "Tardigrade affair" of the 2019 crashed Beresheet lander and its carrying of tardigrades has been discussed as an example for lacking measures and lacking international regulation for planetary protection.

Space debris beyond Earth around the Moon has been considered as a future challenge with increasing numbers of missions to the Moon, particularly as a danger for such missions. As such lunar waste management has been raised as an issue which future lunar missions, particularly on the surface, need to tackle.

Beside the remains of human activity on the Moon, there have been some intended permanent installations like the Moon Museum art piece, Apollo 11 goodwill messages, six lunar plaques, the Fallen Astronaut memorial, and other artifacts.

Longterm missions continuing to be active are some orbiters such as the 2009-launched Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter surveilling the Moon for future missions, as well as some Landers such as the 2013-launched Chang'e 3 with its Lunar Ultraviolet Telescope still operational. Five retroreflectors have been installed on the Moon since the 1970s and since used for accurate measurements of the physical librations through laser ranging to the Moon.

There are several missions by different agencies and companies planned to establish a longterm human presence on the Moon, with the Lunar Gateway as the currently most advanced project as part of the Artemis program.

Astronomy from the Moon

The Moon is recognized as an excellent site for telescopes. It is relatively nearby; certain craters near the poles are permanently dark and cold and especially useful for infrared telescopes; and radio telescopes on the far side would be shielded from the radio chatter of Earth. The lunar soil, although it poses a problem for any moving parts of telescopes, can be mixed with carbon nanotubes and epoxies and employed in the construction of mirrors up to 50 meters in diameter. A lunar zenith telescope can be made cheaply with an ionic liquid.

In April 1972, the Apollo 16 mission recorded various astronomical photos and spectra in ultraviolet with the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph.

The Moon has been also a site of Earth observation, particularly culturally as in the photograph called Earthrise. The Earth appears in the Moon's sky with an apparent size of 1° 48′ to 2°, three to four times the size of the Moon or Sun in Earth's sky, or about the apparent width of two little fingers at an arm's length away.

Living on the Moon

The only instances of humans living on the Moon have taken place in an Apollo Lunar Module for several days at a time (for example, during the Apollo 17 mission). One challenge to astronauts during their stay on the surface is that lunar dust sticks to their suits and is carried into their quarters. Astronauts could taste and smell the dust, calling it the "Apollo aroma". This fine lunar dust can cause health issues.

In 2019, at least one plant seed sprouted in an experiment on the Chang'e 4 lander. It was carried from Earth along with other small life in its Lunar Micro Ecosystem.

Legal status

Although Luna landers scattered pennants of the Soviet Union on the Moon, and U.S. flags were symbolically planted at their landing sites by the Apollo astronauts, no nation claims ownership of any part of the Moon's surface. Likewise no private ownership of parts of the Moon, or as a whole, is considered credible.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty defines the Moon and all outer space as the "province of all mankind". It restricts the use of the Moon to peaceful purposes, explicitly banning military installations and weapons of mass destruction. A majority of countries are parties of this treaty. The 1979 Moon Agreement was created to elaborate, and restrict the exploitation of the Moon's resources by any single nation, leaving it to a yet unspecified international regulatory regime. As of January 2020, it has been signed and ratified by 18 nations, none of which have human spaceflight capabilities.

Since 2020, countries have joined the U.S. in their Artemis Accords, which are challenging the treaty. The U.S. has furthermore emphasized in a presidential executive order ("Encouraging International Support for the Recovery and Use of Space Resources.") that "the United States does not view outer space as a 'global commons'" and calls the Moon Agreement "a failed attempt at constraining free enterprise."

With Australia signing and ratifying both the Moon Treaty in 1986 as well as the Artemis Accords in 2020, there has been a discussion if they can be harmonized. In this light an Implementation Agreement for the Moon Treaty has been advocated for, as a way to compensate for the shortcomings of the Moon Treaty and to harmonize it with other laws and agreements such as the Artemis Accords, allowing it to be more widely accepted.

In the face of such increasing commercial and national interest, particularly prospecting territories, U.S. lawmakers have introduced in late 2020 specific regulation for the conservation of historic landing sites and interest groups have argued for making such sites World Heritage Sites and zones of scientific value protected zones, all of which add to the legal availability and territorialization of the Moon.

In 2021, the Declaration of the Rights of the Moon was created by a group of "lawyers, space archaeologists and concerned citizens", drawing on precedents in the Rights of Nature movement and the concept of legal personality for non-human entities in space.

Coordination

In light of future development on the Moon some international and multi-space agency organizations have been created:

- International Lunar Exploration Working Group (ILEWG)

- Moon Village Association (MVA)

- International Space Exploration Coordination Group (ISECG)

In culture and life

Calendar

Since pre-historic times people have taken note of the Moon's phases, its waxing and waning, and used it to keep record of time. Tally sticks, notched bones dating as far back as 20–30,000 years ago, are believed by some to mark the phases of the Moon. The counting of the days between the Moon's phases gave eventually rise to generalized time periods of the full lunar cycle as months, and possibly of its phases as weeks.

The words for the month in a range of different languages carry this relation between the period of the month and the Moon etymologically. The English month as well as moon, and its cognates in other Indo-European languages (e.g. the Latin mensis and Ancient Greek μείς (meis) or μήν (mēn), meaning "month") stem from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root of moon, *méh1nōt, derived from the PIE verbal root *meh1-, "to measure", "indicat[ing] a functional conception of the Moon, i.e. marker of the month" (cf. the English words measure and menstrual). To give another example from a different language family, the Chinese language uses the same word (月) for moon as well as for month, which furthermore can be found in the symbols for the word week (星期).

This lunar timekeeping gave rise to the historically dominant, but varied, lunisolar calendars. The 7th-century Islamic calendar is an example of a purely lunar calendar, where months are traditionally determined by the visual sighting of the hilal, or earliest crescent moon, over the horizon.

Of particular significance has been the occasion of full moon, highlighted and celebrated in a range of calendars and cultures. Around autumnal equinox, the Full Moon is called the Harvest Moon and is celebrated with festivities such as the Harvest Moon Festival of the Chinese Lunar Calendar, its second most important celebration after Chinese New Year.

Furthermore, association of time with the Moon can also be found in religion, such as the ancient Egyptian temporal and lunar deity Khonsu.

Cultural representation

Since prehistoric and ancient times humans have drawn the Moon and have described a range of understandings of it, having prominent importance in different cosmologies, often exhibiting a spirit, being a deity or an aspect, particularly in astrology.

For the representation of the Moon, especially its lunar phases, the crescent symbol (🌙) has been particularly used by many cultures. In writing systems such as Chinese the crescent has developed into the symbol 月, the word for Moon, and in ancient Egyptian it was the symbol 𓇹, which is spelled like the ancient Egyptian lunar deity Iah, meaning Moon.

Iconographically the crescent was used in Mesopotamia as the primary symbol of Nanna/Sîn, the ancient Sumerian lunar deity, who was the father of Innana/Ishtar, the goddess of the planet Venus (symbolized as the eight pointed Star of Ishtar), and Utu/Shamash, the god of the Sun (symbolized as a disc, optionally with eight rays), all three often depicted next to each other. Nanna was later known as Sîn, and was particularly associated with magic and sorcery.

The crescent was further used as an element of lunar deities wearing headgears or crowns in an arrangement reminiscent of horns, as in the case of the ancient Greek Selene or the ancient Egyptian Khonsu. Selene is associated with Artemis and paralleled by the Roman Luna, which both are occasionally depicted driving a chariot, like the Hindu lunar deity Chandra. The different or sharing aspects of deities within pantheons has been observed in many cultures, especially by later or contemporary culture, particularly forming triple deities. The Moon in Roman mythology for example has been associated with Juno and Diana, while Luna being identified as their byname and as part of a triplet (diva triformis) with Diana and Proserpina, Hecate being identified as their binding manifestation as trimorphos.

The star and crescent (☪️) arrangement goes back to the Bronze Age, representing either the Sun and Moon, or the Moon and planet Venus, in combination. It came to represent the goddess Artemis or Hecate, and via the patronage of Hecate came to be used as a symbol of Byzantium, possibly influencing the development of the Ottoman flag, specifically the combination of the Turkish crescent with a star. Since then the heraldric use of the star and crescent proliferated becoming a popular symbol for Islam (as the hilal of the Islamic calendar) and for a range of nations.

In Roman Catholic Marian veneration, the Virgin Mary (Queen of Heaven) has been depicted since the late Middle Ages on a crescent and adorned with stars. In Islam Muhammad is particularly attributed with the Moon through the so-called splitting of the Moon (Arabic: انشقاق القمر) miracle.

The contrast between the brighter highlands and the darker maria have been seen by different cultures forming abstract shapes, which are among others the Man in the Moon or the Moon Rabbit (e.g. the Chinese Tu'er Ye or in Indigenous American mythologies, as with the aspect of the Mayan Moon goddess).

In Western alchemy silver is associated with the Moon, and gold with the Sun.

Modern culture representation

The perception of the Moon in modern times has been informed by telescope enabled modern astronomy and later by spaceflight enabled actual human activity at the Moon, particularly the culturally impactful lunar landings. These new insights inspired cultural references, connecting romantic reflections about the Moon and speculative fiction such as science-fiction dealing with the Moon.

Contemporarily the Moon has been seen as a place for economic expansion into space, with missions prospecting for lunar resources. This has been accompanied with renewed public and critical reflection on humanity's cultural and legal relation to the celestial body, especially regarding colonialism, as in the 1970 poem "Whitey on the Moon". In this light the Moon's nature has been invoked, particularly for lunar conservation and as a common.

![Sumerian cylinder seal and impression, dated c. 2100 BC, of Ḫašḫamer, ensi (governor) of Iškun-Sin c. 2100 BC. The seated figure is probably king Ur-Nammu, bestowing the governorship on Ḫašḫamer, who is led before him by Lamma (protective goddess).[296]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bc/Sumerian_Cylinder_Seal_of_King_Ur-Nammu.jpg/200px-Sumerian_Cylinder_Seal_of_King_Ur-Nammu.jpg)