The genocide of indigenous peoples, colonial genocide, or settler genocide is the elimination of entire communities of indigenous peoples as a part of the process of colonialism. Genocide of the native population is especially likely in cases of settler colonialism, with some scholars arguing that settler colonialism is inherently genocidal.

While the concept of genocide was formulated by Raphael Lemkin in the mid-20th century, the expansion of various Western European colonial powers such as the British and Spanish empires and the subsequent establishment of colonies on indigenous territories frequently involved acts of genocidal violence against indigenous groups in the Americas, Australia, Africa, and Asia. According to Lemkin, colonization was in itself "intrinsically genocidal". He saw this genocide as a two-stage process, the first being the destruction of the indigenous population's way of life. In the second stage, the newcomers impose their way of life on the indigenous group. According to David Maybury-Lewis, imperial and colonial forms of genocide are enacted in two main ways, either through the deliberate clearing of territories of their original inhabitants in order to make them exploitable for purposes of resource extraction or colonial settlements, or through enlisting indigenous peoples as forced laborers in colonial or imperialist projects of resource extraction. The designation of specific events as genocidal is often controversial.

Some scholars, among them Lemkin, have argued that cultural genocide, sometimes called ethnocide, should also be recognized. A people group may continue to exist, but if it is prevented from perpetuating its group identity by prohibitions of its cultural and religious practices, practices which are the basis of its group identity, this may also be considered a form of genocide. Examples that can be considered this form of genocide include the treatment of Tibetans and Uyghurs by the Government of China, the treatment of Native Americans by citizens of the United States and/or agents of the United States government, and the treatment of First Nations peoples by the Canadian government.

Genocide debate

The concept of genocide was coined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin:

New conceptions require new terms. By "genocide" we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. This new word, coined by the author to denote an old practice in its modern development, is made from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing), thus corresponding in its formation to such words as tyrannicide, homicide, infanticide, etc. Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be the disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group.

After World War II and The Holocaust, this concept of genocide was adopted by the United Nations in 1948. For Lemkin, genocide was broadly defined and it included all attempts to destroy a specific ethnic group, whether they are strictly physical, through mass killings, or whether they are strictly cultural or psychological, through oppression and through the destruction of indigenous ways of life.

The UN's definition, which is used in international law, is narrower than Lemkin's definition, and it also states that genocide is: "any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group," as such:

- (a) "Killing members of the group;"

- (b) "Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;"

- (c) "Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;"

- (d) "Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;"

- (e) "Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group."

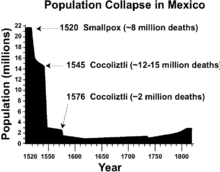

The determination of whether a historical event should or should not be considered a genocide can be a matter of scholarly debate. Historians often draw on broader definitions such as Lemkin's, which sees colonialist violence against indigenous peoples as inherently genocidal. For example, in the case of the colonization of the Americas, where the indigenous people of the Americas declined by up to 90% in the first centuries of European colonization, how much of the population decline is attributable to genocide is debatable because disease is considered the main cause of this decline due to the fact that the introduction of disease was partially unintentional. Some genocide scholars separate the population declines which are due to disease from the genocidal aggression of one group towards another. Some scholars argue that an intent to commit a genocide is not needed, because a genocide may be the cumulative result of minor conflicts in which settlers, colonial agents or state agents perpetrate violent acts against minority groups. Others argue that the dire consequences of European diseases among many New World populations were exacerbated by different forms of genocidal violence, and they also argue that intentional deaths and unintentional deaths cannot easily be separated from each other. Some scholars regard the colonization of the Americas as genocide, since they argue it was largely achieved through systematically exploiting, removing and destroying specific ethnic groups, which would create environments and conditions for such disease to proliferate.

According to a 2020 study by Tai S Edwards and Paul Kelton, recent scholarship shows "that colonizers bear responsibility for creating conditions that made natives vulnerable to infection, increased mortality, and hindered population recovery. This responsibility intersected with more intentional and direct forms of violence to depopulate the Americas... germs can no longer serve as the basis for denying American genocides."

Indigenous peoples of the Americas (pre-1948)

It is estimated that during the initial Spanish conquest of the Americas, up to eight million indigenous people died, primarily through the spread of Afro-Eurasian diseases. Simultaneously, wars and atrocities waged by Europeans against Native Americans also resulted in millions of deaths. Mistreatment and killing of Native Americans continued for centuries, in every area of the Americas, including the areas that would become Canada, the United States, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Chile. In the United States, some scholars (examples listed below) state that the American Indian Wars and the doctrine of manifest destiny contributed to the genocide, with one major event cited being the Trail of Tears.

Categorization as a genocide

Historians and scholars whose work has examined this history in the context of genocide have included historian Jeffrey Ostler, historian David Stannard, anthropological demographer Russell Thornton, Indigenous Studies scholar Vine Deloria, Jr., as well as scholar-activists such as Russell Means and Ward Churchill. In his book, American Holocaust Stannard compares the events of colonization in the Americas to the definition of genocide which is written in the 1948 UN convention, and he writes that,

In light of the U.N. language—even putting aside some of its looser constructions—it is impossible to know what transpired in the Americas during the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries and not conclude that it was genocide.

Thornton describes the direct consequences of warfare, violence and massacres as genocides, many of which had the effect of wiping out entire ethnic groups. Political scientist Guenter Lewy states that "even if up to 90 percent of the reduction in Indian population was the result of disease, that leaves a sizable death toll caused by mistreatment and violence." Native American studies professor Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz states,

Proponents of the default position emphasize attrition by disease despite other causes equally deadly, if not more so. In doing so they refuse to accept that the colonization of America was genocidal by plan, not simply the tragic fate of populations lacking immunity to disease.

By 1900, the indigenous population in the Americas declined by more than 80%, and by as much as 98% in some areas. The effects of diseases such as smallpox, measles and cholera during the first century of colonialism contributed greatly to the death toll, while violence, displacement and warfare against the Indians by colonizers contributed to the death toll in subsequent centuries. As detailed in American Philosophy: From Wounded Knee to the Present (2015),

It is also apparent that the shared history of the hemisphere is one which is framed by the dual tragedies of genocide and slavery, both of which are part of the legacy of the European invasions of the past 500 years. Indigenous people both north and south were displaced, died of disease, and were killed by Europeans through slavery, rape, and war. In 1491, about 145 million people lived in the western hemisphere. By 1691, the population of indigenous Americans had declined by 90–95 percent, or by around 130 million people.

According to geographers from University College London, the colonization of the Americas by Europeans killed so many people it resulted in climate change and global cooling. UCL Geography Professor Mark Maslin, one of the co-authors of the study, states that the large death toll also boosted the economies of Europe: "the depopulation of the Americas may have inadvertently allowed the Europeans to dominate the world. It also allowed for the Industrial Revolution and for Europeans to continue that domination."

Spanish colonization of the Americas

It is estimated that during the initial Spanish conquest of the Americas up to eight million indigenous people died, primarily through the spread of Afro-Eurasian diseases, in a series of events that have been described as the first large-scale act of genocide of the modern era.

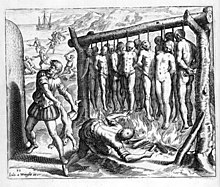

Acts of brutality and systematic annihilation against the Taíno People of the Caribbean prompted Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas to write Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias ('A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies') in 1542—an account that had a wide impact throughout the western world as well as contributing to the abolition of indigenous slavery in all Spanish territories the same year it was written.

Las Casas wrote that the native population on the Spanish colony of Hispaniola had been reduced from 400,000 to 200 in a few decades. His writings were among those that gave rise to Spanish Black Legend, which Charles Gibson describes as "the accumulated tradition of propaganda and Hispanophobia according to which the Spanish Empire is regarded as cruel, bigoted, degenerate, exploitative and self-righteous in excess of reality".

Historian Andrés Reséndez at the University of California, Davis asserts that even though disease was a factor, the indigenous population of Hispaniola would have rebounded the same way Europeans did following the Black Death if it were not for the constant enslavement they were subject to. He says that "among these human factors, slavery was the major killer" of Hispaniola's population, and that "between 1492 and 1550, a nexus of slavery, overwork and famine killed more natives in the Caribbean than smallpox, influenza or malaria."

Noble David Cook said about the Black Legend conquest of the Americas: "There were too few Spaniards to have killed the millions who were reported to have died in the first century after Old and New World contact." Instead, he estimates that the death toll was caused by diseases like smallpox, which according to some estimates had an 80–90% fatality rate in Native American populations. However, historian Jeffrey Ostler has argued that Spanish colonization created conditions for disease to spread, for example, "careful studies have revealed that it is highly unlikely that members" of Hernando de Soto's 1539 expedition in the American South "had smallpox or measles. Instead, the disruptions caused by the expedition increased the vulnerability of Native people to diseases including syphilis and dysentery, already present in the Americas, and malaria, a disease recently introduced from the eastern hemisphere."

With the initial conquest of the Americas completed, the Spanish implemented the encomienda system in 1503. In theory, the encomienda placed groups of indigenous peoples under Spanish oversight to foster cultural assimilation and conversion to Catholicism, but in practice it led to the legally sanctioned forced labor and resource extraction under brutal conditions with a high death rate. Though the Spaniards did not set out to exterminate the indigenous peoples, believing their numbers to be inexhaustible, their actions led to the annihilation of entire tribes such as the Arawak. Many Arawaks died from lethal forced labor in the mines, where a third of workers died every six months. According to historian David Stannard, the encomienda was a genocidal system which "had driven many millions of native peoples in Central and South America to early and agonizing deaths."

According to Doctor Clifford Trafzer, Professor at UC Riverside, in the 1760s, an expedition dispatched to fortify California, led by Gaspar de Portolà and Junípero Serra, was marked by slavery, forced conversions, and genocide through the introduction of disease.

British colonization of the Americas

Beaver Wars

During the Beaver Wars of the seventeenth century, the Iroquois effectively destroyed several large tribal confederacies, including the Mohicans, Huron (Wyandot), Neutral, Erie, Susquehannock (Conestoga), and northern Algonquins, with the extreme brutality and exterminatory nature of the mode of warfare practised by the Iroquois causing some historians to label these wars as acts of genocide committed by the Iroquois Confederacy.

Kalinago genocide, 1626

The Kalinago genocide was the massacre of some 2,000 Island Caribs in St. Kitts by English and French settlers in 1628.

The Carib Chief Tegremond became uneasy with the increasing number of English and French settlers occupying St. Kitts. This led to confrontations, which led him to plot the settlers' elimination with the aid of other Island Caribs. However, his scheme was betrayed by an Indian woman called Barbe, to Thomas Warner and Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc. Taking action, the English and French settlers invited the Caribs to a party where they became intoxicated. When the Caribs returned to their village, 120 were killed in their sleep, including Chief Tegremond. The following day, the remaining 2,000–4,000 Caribs were forced into the area of Bloody Point and Bloody River, where over 2,000 were massacred, though 100 settlers were also killed. One Frenchman went mad after being struck by a manchineel-poisoned arrow. The remaining Caribs fled. Later, by 1640, those not already enslaved were removed to Dominica.

Attempted extermination of the Pequot, 1636–1638

The Pequot War was an armed conflict that took place between 1636 and 1638 in New England between the Pequot tribe and an alliance of the colonists of the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Saybrook colonies and their allies from the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes.

The war concluded with the decisive defeat of the Pequots. The colonies of Connecticut and Massachusetts offered bounties for the heads of killed hostile Indians, and later for just their scalps, during the Pequot War in the 1630s; Connecticut specifically reimbursed Mohegans for slaying the Pequot in 1637. At the end, about 700 Pequots had been killed or taken into captivity. Hundreds of prisoners were sold into slavery to the West Indies; other survivors were dispersed as captives to the victorious tribes. The result was the elimination of the Pequot tribe as a viable polity in Southern New England, the colonial authorities classifying them as extinct. However, members of the Pequot tribe still live today as a federally recognized tribe.

Massacre of the Narragansett people, 1675

The Great Swamp Massacre was committed during King Philip's War by colonial militia of New England on the Narragansett tribe in December 1675. On December 15 of that year, Narraganset warriors attacked the Jireh Bull Blockhouse and killed at least 15 people. Four days later, the militias from the English colonies of Plymouth, Connecticut, and Massachusetts Bay were led to the main Narragansett town in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The settlement was burned, its inhabitants (including women and children) killed or evicted, and most of the tribe's winter stores destroyed. It is believed that at least 97 Narragansett warriors and 300 to 1,000 non-combatants were killed, though exact figures are unknown. The massacre was a critical blow to the Narragansett tribe during the period directly following the massacre. However, much like the Pequot, the Narragansett people continue to live today as a federally recognized tribe.

French and Indian War and Pontiac's War, 1754–1763

On 12 June 1755, during the French and Indian War, Massachusetts governor William Shirley issued a bounty of £40 for a male Indian scalp, and £20 for scalps of Indian females or of children under 12 years old. In 1756, Pennsylvania lieutenant-governor Robert Hunter Morris, in his declaration of war against the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) people, offered "130 Pieces of Eight, for the Scalp of Every Male Indian Enemy, above the Age of Twelve Years", and "50 Pieces of Eight for the Scalp of Every Indian Woman, produced as evidence of their being killed." During Pontiac's War, Colonel Henry Bouquet conspired with his superior, Sir Jeffrey Amherst, to infect hostile Native Americans through biological warfare with smallpox blankets.

Canada

Although not without conflict, European Canadians' early interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful. First Nations and Métis peoples played a critical part in the development of European colonies in Canada, particularly for their role in assisting European coureur des bois and voyageurs in their explorations of the continent during the North American fur trade. These early European interactions with First Nations would change from friendship and peace treaties to dispossession of lands through treaties. From the late 18th century, European Canadians forced Indigenous peoples to assimilate into a western Canadian society. These attempts reached a climax in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with forced integration and relocations.

As a consequence of European colonization, the Indigenous population declined by forty to eighty percent. The decline is attributed to several causes, including the transfer of European diseases, such as influenza, measles, and smallpox to which they had no natural immunity, conflicts over the fur trade, conflicts with the colonial authorities and settlers, and the loss of Indigenous lands to settlers and the subsequent collapse of several nations' self-sufficiency.

With the death of Shanawdithit in 1829, the Beothuk people, and the indigenous people of Newfoundland were officially declared extinct after suffering epidemics, starvation, loss of access to food sources, and displacement by English and French fishermen and traders. Scholars disagree in their definition of genocide in relation to the Beothuk, and the parties have different political agendas. While some scholars believe that the Beothuk died out due to the elements noted above, another theory is that Europeans conducted a sustained campaign of genocide against them. More recent understandings of the concept of "cultural genocide" and its relation to settler colonialism have led modern scholars to a renewed discussion of the genocidal aspects of the Canadian states' role in producing and legitimating the process of physical and cultural destruction of Indigenous people. In the 1990s some scholars began pushing for Canada to recognize the Canadian Indian residential school system as a genocidal process rooted in colonialism. This public debate led to the formation of the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission which was formed in 2008.

The Canadian Indian residential school system was established following the passage of the Indian Act in 1876. The system was designed to remove children from the influence of their families and culture with the aim of assimilating them into the dominant Canadian culture. The final school closed in 1996. Over the course of the system's existence, about 30% of native children, or roughly 150,000, were placed in residential schools nationally; at least 6,000 of these students died while in attendance. The system has been described as cultural genocide: "killing the Indian in the child". Part of this process during the 1960s through the 1980s, dubbed the Sixties Scoop, was investigated and the child seizures deemed genocidal by Judge Edwin Kimelman, who wrote: "You took a child from his or her specific culture and you placed him into a foreign culture without any [counselling] assistance to the family which had the child. There is something dramatically and basically wrong with that." Another aspect of the residential school system was its use of forced sterilization on Indigenous women who chose not to follow the schools advice of marrying non-Indigenous men. Indigenous women made up only 2.5% of the Canadian population, but 25% of those who were sterilized under the Canadian eugenics laws (such as the Sexual Sterilization Act of Alberta) – many without their knowledge or consent.

The Executive Summary of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found that the state pursued a policy of cultural genocide through forced assimilation. The ambiguity of the phrasing allowed for the interpretation that physical and biological genocide also occurred. The commission, however, was not authorized to conclude that physical and biological genocide occurred, as such a finding would imply a difficult to prove legal responsibility for the Canadian government. As a result, the debate about whether the Canadian government also committed physical and biological genocide against Indigenous populations remains open.

The use of cultural genocide is used to differentiate from the Holocaust: a clearly accepted genocide in history. Some argue that this description negates the biological and physical acts of genocide that occurred in tandem with cultural destruction. When engaged within the context of international law, colonialism in Canada has inflicted each criterion for the United Nations definition of the crime of genocide. However, all examples below of physical genocide are still highly debated as the requirement of intention and overall motivations behind the perpetrators actions is not widely agreed upon as of yet.

Canada's actions towards Indigenous peoples can be categorized under the first example of the UN definition of genocide, "killing members of the group", through the spreading of deadly disease such as during the 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic. Further examples from other parts of the country include the Saskatoon's freezing deaths, the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirited people, and the scalping bounties offered by the governor of Nova Scotia, Edward Cornwallis.

Secondly, as affirmed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the residential school system was a clear example of (b) and (e) and similar acts continue to this day through the Millennium Scoop, as Indigenous children are disproportionately removed from their families and placed into the care of others who are often of different cultures through the Canadian child welfare system. Once again this repeats the separation of Indigenous children from their traditional ways of life. Moreover, children living on-reserve are subject to inadequate funding for social services which has led to filing of a ninth non-compliance order in early 2021 to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal in attempts to hold the Canadian government accountable.

Subsection (c) of the UN definition: "deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part" is an act of genocide that has historic legacies, such as the near and full extrapolation of caribou and bison that contributed to mass famines in Indigenous communities, how on reserve conditions infringe on the quality of life of Indigenous peoples as their social services are underfunded and inaccessible, and hold the bleakest water qualities in the first world country. Canada also situates precarious and lethal ecological toxicities that pose threats to the land, water, air and peoples themselves near or on Indigenous territories. Indigenous people continue to report (d), the "imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group", within more recent years. Specifically through the avoidance of informed consent surrounding sterilization procedures with Indigenous people like the case of D.D.S. represented by lawyer Alisa Lombard from 2018 in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. Examples such as the ones listed above have led to widespread physical and virtual action across the country to protest the historical and current genocidal harms faced by Indigenous peoples.

On July 28, 2022, during the visit by Pope Francis to Canada at the Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral, the Pope stated: "And thinking about the process of healing and reconciliation with our indigenous brothers and sisters, never again can the Christian community allow itself to be infected by the idea that one culture is superior to others, or that it is legitimate to employ ways of coercing others." Pope Francis on his return flight to Rome on July 30, 2022, after a week-long trip to Canada, responded to a question from a journalist: "It's true, I didn't use the word because it didn't occur to me, but I described the genocide and asked for pardon, forgiveness for this work that is genocidal. For example, I condemned this too: Taking away children and changing culture, changing mentalities, changing traditions, changing a race, let's say, a whole culture. Yes, it's a technical word, genocide, but I didn't use it because it didn't come to mind, but I described it. It is true; yes, it's genocide. Yes, you all, be calm. You can say that I said that, yes, that it was genocide."

Mexico

Apaches

In 1835, the government of the Mexican state of Sonora put a bounty on the Apache which, over time, evolved into a payment by the government of 100 pesos for each scalp of a male 14 or more years old. In 1837, the Mexican state of Chihuahua also offered a bounty on Apache scalps, 100 pesos per warrior, 50 pesos per woman, and 25 pesos per child.

Mayas

The Caste War of Yucatán was caused by encroachment of colonizers on communal land of Mayas in Southeast Mexico. According to political scientist Adam Jones: "This ferocious race war featured genocidal atrocities on both sides, with up to 200,000 killed."

Yaquis

The Mexican government's response to the various uprisings of the Yaqui tribe have been likened to genocide particularly under Porfirio Diaz. Due to massacre, the population of the Yaqui tribe in Mexico was reduced from 30,000 to 7,000 under Diaz's rule. One source estimates at least 20,000 out of these Yaquis were victims of state murders in Sonora. Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador said he would be willing to offer apologies for the abuses in 2019.

Argentina

Argentina launched campaigns of territorial expansion in the second half of the 19th century, at the expense of Indigenous peoples and neighbor state Chile. Mapuche people were forced from their ancestral lands by Argentinian military forces, resulting in deaths and displacements. During the 1870s, President Julio Argentino Roca implemented the Conquest of the Desert (Spanish: Conquista del desierto) military operation, which resulted in the subjugation, enslavement, and genocide of Mapuche individuals residing in the Pampas area.

In southern Patagonia, both Argentina and Chile occupied indigenous lands and waters, and facilitated the genocide implemented by sheep-farmers and businessmen in Tierra del Fuego. Starting in the late 19th century, during the Tierra del Fuego Gold Rush, European settlers, in concert with the Argentine and Chilean governments, systematically exterminated the Selk'nam people, Yaghan, and Haush peoples. Their decimation is known today as the Selk'nam genocide.

Argentina also expanded northward, dispossessing a number of Chaco peoples through a policy that may be considered as genocidal.

Paraguay

The War of the Triple Alliance (1865-1870) was launched by the Empire of Brazil, in alliance with the Argentinian government of Bartolomé Mitre and the Uruguayan government of Venancio Flores, against Paraguay. The governments of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay signed a secret treaty in which the "high contracting parties" solemnly bind themselves to overthrow the government of Paraguay. In the five years of war, the Paraguayan population was reduced, including civilians, women, children, and the elderly. Julio José Chiavenato, in his book American Genocide, affirms that it was "a war of total extermination that only ended when there were no more Paraguayans to kill" and concludes that 99.5% of the adult male population of Paraguay died during the war. Out of a population of approximately 420,000 before the war, only 14,000 men and 180,000 women remained.

Author Steven Pinker wrote:

Among its many wars (19th century) is the War of the Triple Alliance, which may have killed 400,000 people, including more than 60 percent of the population of Paraguay, making it proportionally the most destructive war in modern times.

Chile

The so-called Pacification of the Araucania by the Chilean army dispossessed the up-to-then independent Mapuche people between the 1860s and the 1880s. First during the Arauco War and then during the Occupation of Araucanía, there was a long-running conflict with the Mapuche people, mostly fought in the Araucanía.

United States colonization of indigenous territories

Stacie Martin states that the United States has not been legally admonished by the international community for genocidal acts against its indigenous population, but many historians and academics describe events such as the Mystic massacre, the Trail of Tears, the Sand Creek massacre and the Mendocino War as genocidal in nature.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz states that U.S. history, as well as inherited Indigenous trauma, cannot be understood without dealing with the genocide that the United States committed against Indigenous peoples. From the colonial period through the founding of the United States and continuing in the twentieth century, this has entailed torture, terror, sexual abuse, massacres, systematic military occupations, removals of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories via Indian removal policies, forced removal of Native American children to military-like boarding schools, allotment, and a policy of termination.

The letters exchanged between Bouquet and Amherst during the Pontiac War show Amherst writing to Bouquet the Indigenous people needed to be exterminated:

"You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execreble race."

Historians regard this as evidence of a genocidal intent by Amherst, as well as part of a broader genocidal attitude frequently displayed against Native Americans during the colonization of the Americas. When smallpox swept the northern plains of the U.S. in 1837, the U.S. Secretary of War Lewis Cass ordered that no Mandan (along with the Arikara, the Cree, and the Blackfeet) be given smallpox vaccinations, which were provided to other tribes in other areas.

The United States has to date not undertaken any truth commission nor built a memorial for the genocide of indigenous people. It does not acknowledge nor compensate for the historical violence against Native Americans that occurred during territorial expansion to the west coast. American museums such as the Smithsonian Institution do not dedicate a section to the genocide. In 2013, the National Congress of American Indians passed a resolution to create a space for the National American Indian Holocaust Museum inside the Smithsonian, but it was ignored by the latter.

Sterilization of natives

The Family Planning Services and Population Research Act was passed in 1970, which subsidized sterilizations for patients receiving healthcare through the Indian Health Service. In the six years after the act was passed, an estimated 25% of childbearing-aged Native American women were sterilized. Some of the procedures were performed under coercion, or without understanding by those sterilized. In 1977, Marie Sanchez, chief tribal judge of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation told the United Nations Convention on Indigenous Rights in Geneva, that Native American women suffered involuntary sterilization which she equated with modern genocide.

Native American boarding schools

The Native American boarding school system was a 150-year program and federal policy which separated Indigenous children from their families and sought to assimilate them into white society. It began in the early 19th century, coinciding with the start of Indian Removal policies. A Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report was published on May 11, 2022, which officially acknowledged the federal government's role in creating and perpetuating this system. According to the report, the U.S. federal government operated or funded more than 408 boarding institutions in 37 states between 1819 and 1969. 431 boarding schools were identified in total, many of which were run by religious institutions. The report described the system as part of a federal policy aimed at eradicating the identity of Indigenous communities and confiscating their lands. Abuse was widespread at the schools, as was overcrowding, malnutrition, disease and lack of adequate healthcare. The report documented over 500 child deaths at 19 schools, although it is estimated the total number could rise to thousands, and possibly even tens of thousands. Marked or unmarked burial sites were discovered at 53 schools. The school system has been described as a cultural genocide and a racist dehumanization.

Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears

Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the American government began forcibly relocating East Coast tribes across the Mississippi. The removal included many members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations, among others in the United States, from their homelands to the Indian Territory in the eastern sections of the present-day state of Oklahoma. About 2,500–6,000 died along the Trail of Tears.

Chalk and Jonassohn assert that the deportation of the Cherokee tribe along the Trail of Tears would almost certainly be considered an act of genocide today. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the exodus. About 17,000 Cherokees, along with approximately 2,000 Cherokee-owned black slaves, were removed from their homes. The number of people who died as a result of the Trail of Tears has been variously estimated. American doctor and missionary Elizur Butler, who made the journey with one party, estimated 4,000 deaths.

Historians such as David Stannard and Barbara Mann have noted that the army deliberately routed the march of the Cherokee to pass through areas of a known cholera epidemic, such as Vicksburg. Stannard estimates that during the forced removal from their homelands, following the Indian Removal Act signed into law by President Andrew Jackson in 1830, 8,000 Cherokee died, about half the total population.

American Indian Wars

During the American Indian Wars, the American Army carried out a number of massacres and forced relocations of Indigenous peoples that are sometimes considered genocide. The 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, which caused outrage in its own time, has been regarded as a genocide. Colonel John Chivington led a 700-man force of Colorado Territory militia in a massacre of 70–163 peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho, about two-thirds of whom were women, children, and infants. Chivington and his men took scalps and other body parts as trophies, including human fetuses and male and female genitalia. In defense of his actions, Chivington stated,

Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! ... I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God's heaven to kill Indians. ... Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.

— - Col. John Milton Chivington, U.S. Army

United States acquisition of California

The U.S. colonization of California started in earnest in 1845, with the Mexican–American War. With the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it gave the United States authority over 525,000 square miles of new territory. In addition to the Gold Rush slaughter, there was also a large number of state-subsidized massacres by colonists against Native Americans in the territory, causing several entire ethnic groups to be wiped out.

In one such series of conflicts, the so-called Mendocino War and the subsequent Round Valley War, the entirety of the Yuki people was brought to the brink of extinction. From a previous population of some 3,500 people, fewer than 100 members of the Yuki tribe were left. According to Russell Thornton, estimates of the pre-Columbian population of California may have been as high as 300,000.

By 1849, due to a number of epidemics, the number had decreased to 150,000. But from 1849 and up until 1890 the Indigenous population of California had fallen below 20,000, primarily because of the killings. At least 4,500 California Indians were killed between 1849 and 1870, while many more perished due to disease and starvation. 10,000 Indians were also kidnapped and sold as slaves. In a speech before representatives of Native American peoples in June 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom apologized for the genocide. Newsom said, "That's what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that's the way it needs to be described in the history books."

One California law made it legal to declare any jobless Indian a vagrant, then auction his services off for up to four months. It also permitted whites to force Indian children to work for them until they were eighteen, provided that they first obtain permission from what the law referred to as a 'friend'. Whites hunted down adult Indians in the mountains, kidnapped their children, and sold them as apprentices for as little as $50. Indians could not complain in court because of another California statute that stated that 'no Indian or Black or Mulatto person was permitted to give evidence in favor of or against a white person'. One contemporary wrote, "The miners are sometimes guilty of the most brutal acts with the Indians... such incidents have fallen under my notice that would make humanity weep and men disown their race". The towns of Marysville and Honey Lake paid bounties for Indian scalps. Shasta City offered $5 for every Indian head brought to City Hall; California's State Treasury reimbursed many of the local governments for their expenses.

March across Samar

During the Philippine–American War, on September 28, 1901, Filipino forces defeated and nearly wiped out a US company in the Battle of Balangiga. In response, US forces carried out widespread atrocities during the March across Samar, which lasted from December, 1901 to February, 1902. US forces killed between 2,000 and 2,500 Filipino civilians, according to most sources, and carried out an extensive scorched-earth policy, which included burning down villages. Some Filipino historians have called these killings genocidal. U.S. Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith instructed his soldiers to "kill everyone over ten years old", including children who were capable of bearing arms, and to take no prisoners. However, Major Littleton Waller, commanding officer of a battalion of 315 US Marines, refused to follow his orders. Some Filipino historians estimate higher at 5,000 killed during the campaign, while other estimates are as high as 50,000.

Politics of modern Brazil

Over 80 indigenous tribes disappeared between 1900 and 1957. During this period, out of a population of over one million, 80% had been killed through deculturalization, disease, or murder. It has also been argued that genocide has occurred during the modern era with the ongoing destruction of the Jivaro, Yanomami, and other tribes.

Indigenous peoples of Africa (pre-1948)

French colonization of Africa

Algeria

Over the course of the French conquest of Algeria and immediately after it, a series of demographic catastrophes ensued in Algeria between 1830 and 1871. Because the demographic crisis was so severe, Dr. René Ricoux, head of demographic and medical statistics at the statistical office of the General Government of Algeria, foresaw the simple disappearance of Algerian "natives as a whole". The demographic change in Algeria can be divided into three phases: an almost constant decline during the conquest period, up until its heaviest drop from an estimated 2.7 million in 1861 to 2.1 million in 1871, and finally moving into a gradual increase to a level of three million inhabitants by 1890. The causes range from a series of famines, diseases, and emigration to the violent methods used by the French army during their Pacification of Algeria, which historians argue constitute acts of genocide.

Congo Free State

Under Leopold II of Belgium, the population loss in the Congo Free State is estimated at sixty percent, up to 15 million people having been killed. The Congo Free State was hit especially hard by sleeping sickness and smallpox epidemics.

Genocide in German South West Africa

Atrocities against the indigenous African population by the German colonial empire can be dated to the earliest German settlements on the continent. The German colonial authorities carried out a genocide in German South-West Africa (GSWA) and incarcerated the survivors in concentration camps. It was also reported that, between 1885 and 1918, the indigenous population of Togo, German East Africa (GEA) and the Cameroons suffered from various human rights abuses, including starvation from scorched earth tactics and forced relocation for use as labor.

The German Empire's action in GSWA against the Herero tribe is considered by Howard Ball to be the first genocide of the 20th century. After the Herero, Namaqua and Damara began an uprising against the colonial government, General Lothar von Trotha, appointed as head of the German forces in GSWA by Emperor Wilhelm II in 1904, gave German forces the order to push them into the desert where they would die. Germany apologized for the genocide in 2004.

While many argue that the military campaign in Tanzania to suppress the Maji Maji Rebellion in GEA between 1905 and 1907 was not an act of genocide, as the military did not have as an intentional goal the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Africans, according to Dominik J. Schaller, the statement released at the time by Governor Gustav Adolf von Götzen did not exculpate him from the charge of genocide, but was proof that the German administration knew that their scorched earth methods would result in famine. 200,000 Africans are estimated to have died from famine, with some areas having been left completely and permanently devoid of human life.

Indigenous peoples of Asia (pre-1948)

Russian tsarist conquest of Siberia

The Russian conquest of Siberia was accompanied by massacres due to indigenous resistance to colonization by the Russian Cossacks, who savagely crushed the natives. At the hands of people like Vasilii Poyarkov in 1645 and Yerofei Khabarov in 1650, some peoples like the Daur were slaughtered by the Russians to the extent that it is considered genocide. In Kamchatka, out of a previous population of 20,000, only 8,000 remained after being subjected to half a century of Cossack slaughter.

In the 1640s the Yakuts were subjected to massacres during the Russian advance into their land near the Lena River, and on Kamchatka in the 1690s the Koryak, Kamchadals, and Chukchi were also subjected to massacres by the Russians. When the Russians did not obtain the demanded amount of fur tribute from the natives, Yakutsk Governor Peter Golovin, who was a Cossack, used meat hooks to hang the native men. In the Lena basin, 70% of the Yakut population died within 40 years, native women and children having been raped and enslaved in order to force the tribe to pay the tribute.

In Kamchatka, the Russians savagely crushed the Itelmens uprisings against their rule in 1706, 1731, and 1741. The first time the Itelmen were armed with stone weapons and were unprepared. However, the second time, they used gunpowder weapons. The Russians faced tougher resistance when from 1745 to 1756 they tried to exterminate the gun and bow-equipped Koraks until their victory. The Russian Cossacks also faced fierce resistance and were forced to give up when trying unsuccessfully to wipe out the Chukchi through genocide in 1729, 1730–1731, and 1744–1747.

After the Chukchi defeated the Russians in 1729, Russian commander Major Pavlutskiy waged war against them. Chukchi women and children were mass-slaughtered and enslaved in 1730–1731. Empress Elizabeth ordered the Chukchis and the Koraks be genocided in 1742 to totally expel them from their native lands and erase their culture through war. Her command was that the natives be "totally extirpated", with Pavlutskiy leading the war from 1744 to 1747. The Chukchi ended the campaign and forced the Russian army to give up by killing Pavlitskiy and decapitating him.

The Russians also waged war and slaughtered the Koraks in 1744 and 1753–1754. After the Russians tried to force them to convert to Christianity, the different native peoples (the Koraks, Chukchis, Itelmens, and Yukagirs) all united to drive them out of their land in the 1740s, culminating in the assault on Nizhnekamchatsk fort in 1746.

Nowadays, Kamchatka is European in demographics and culture. Indigenous Kamchatkans only make up 2.5% of the population, which accounts for around 10,000 people out of a previous number of 150,000. The genocide committed by the Cossacks, as well as the fur trade which devastated local wildlife, exterminated much of the native indigenous population. In addition, the Cossacks also devastated the local wildlife by slaughtering massive numbers of animals for fur. Between the eighteenth and the nineteenth century, 90% of the Kamchadals and half of the Vogules were killed. The rapid genocide of the indigenous population led to entire ethnic groups being entirely wiped out, with around 12 exterminated groups which could be named by Nikolai Iadrintsev as of 1882.

In the Aleutian islands, the Aleut natives were subjected to genocide and slavery by the Russians for the first 20 years of Russian rule, Aleut women and children being captured by the Russians and Aleut men slaughtered.

The Russian colonization of Siberia and the treatment of the indigenous peoples has been compared to the European colonization of the Americas, with similar negative impacts on the indigenous Siberians as upon the indigenous peoples of the Americas. One of these commonalities is the appropriation of indigenous peoples' land.

Japanese Empire

Colonization of Hokkaido

The Ainu are an indigenous people in Japan (Hokkaidō). In a 2009 news story, Japan Today reported, "Many Ainu were forced to work, essentially as slaves, for Wajin (ethnic Japanese), resulting in the breakup of families and the introduction of smallpox, measles, cholera and tuberculosis into their community. In 1869, the new Meiji government renamed Ezo as Hokkaido and unilaterally incorporated it into Japan. It banned the Ainu language, took Ainu land away, and prohibited salmon fishing and deer hunting."

Roy Thomas wrote: "Ill treatment of native peoples is common to all colonial powers, and, at its worst, leads to genocide. Japan's native people, the Ainu, have, however, been the object of a particularly cruel hoax, as the Japanese have refused to accept them officially as a separate minority people."

The Ainu have emphasized that they were the natives of the Kuril islands and the southern half of Sakhalin, which both Japan and Russia invaded. In 2004, the small Ainu community living in Kamchatka Krai, Russia wrote a letter to Vladimir Putin, urging him to reconsider any move to award the Southern Kuril islands to Japan. In the letter, they blamed the Japanese, the Tsarist Russians and the Soviets for crimes against the Ainu such as killings and assimilation, and also urged him to recognize the Japanese genocide against the Ainu people, which Putin turned down.

Colonization of Okinawa

Okinawans are an indigenous people to the islands to the west of Japan, originally known as the Ryukyu Islands. With skeletons dating back 32,000 years, the Okinawan or Ryukyu people have a long history on the islands that includes a kingdom of its own known as the Ryukyu Kingdom. The kingdom established trade relationships with China and Japan that began in the late 1500s and lasted until the 1860s.

In the 1590s, Japan made its first attempt at subjecting the Ryukyu Kingdom by sending a group of 3,000 samurai armed with muskets to conquer the Ryukyu kingdom. Indefinite take over was not achieved; however, the Ryukyu Kingdom became an acting colony of Japan. As a result, it paid homage to the Japanese while feigning their own independence to China to maintain trade.

In 1879, after a small rebellion by the Ryukyu people was squelched, the Japanese government (the Ryukyu people had requested help from China to break all bonds from Japan) punished Ryukyu by officially naming it a state of Japan and re branding the kingdom as Okinawa. Much like the Ainu, Ryukyuans were punished for speaking their own language, forced to identify with Japanese myths and legends (forgoing their own legends), adopt Japanese names, and reorient their religion around the Japanese Emperor. Their homeland was also renamed Okinawa. Japan had officially expanded their colonization to the Okinawan islands, where natives didn't play a significant role in Japan's history until the end of World War II.

When America brought the war to Japan, the first area that was effected were the Okinawan Islands. Okinawan citizens forced into becoming soldiers were told that Americans would take no prisoners. In addition to the warnings, Okinawans were given a grenade per household, its use reserved in case Americans gained control of the island, with the standing orders to have a member of the household gather everyone and pull the pin for mass suicide. Okinawans were told this was to avoid the "inevitable" torture that would follow any occupation. In addition, the Japanese army kicked any natives out of their homes that weren't currently serving in the army (women and children included) and forced them into open, unprotected, spaces such as beaches and caves. These happened to be the first places the Americans arrived on in the island. As a result, more than 120,000 Okinawans (between a quarter and a third of the population) died, soldiers and civilians alike. Americans took over the island and the war was soon over. America launched their main base in Asia from Okinawa and the Emperor of Japan approved, giving Okinawa to America for an agreed 25–50 years to move the majority of Americans out of mainland Japan. In the end, Americans stayed in Okinawa for 74 years, without showing any signs of leaving. During the occupation, Okinawan natives were forced to give up their best cultivating land to Americans which they keep to this day.

Issues in Okinawa have yet to be resolved regarding the expired stay of American soldiers. Although Okinawa was given back to Japan, the American base still stays. The Japanese government has yet to take action, despite Okinawans raising the Issue. However, this is not the only problem that the Japanese government has refused to take action on. Okinawans were ruled an Indigenous people in 2008 by the committee of the United Nations (UN), in addition to their original languages being recognized as endangered or severely endangered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The UN has encouraged that Okinawan history and language be mandatorily taught in schools in Okinawa, but nothing has been done so far. Okinawans are still in a cultural struggle that matches that of the Ainu people. They are not allowed to be Japanese-Okinawan, Japanese being the only nationally or legally accepted term.

Genocide of Oroqen and Hezhen

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), the Japanese performed "bacterial experiments" on the Oroqen people. They introduced them to opium which caused their population to decline until only 1,000 of them remained alive at the end of the war. The Japanese banned them from communicating with members of other ethnicities, and forced them to hunt animals for them in exchange for starvation rations and unsuitable clothing which caused them to die from exposure to the inclement weather. The Japanese also forced Oroqen adults who were older than 18 to take opium. After 2 Japanese troops were killed in Alihe by an Oroqen hunter, the Japanese poisoned 40 Oroqen to death. The Japanese forced the Oroqen to fight the war for them which led to a decrease in the Oroqen population.

The Hezhen population declined by 90% due to deaths from forced opium use, slave labor and relocation by the Japanese. When the Japanese were defeated in 1945, only 300 Hezhen were left alive out of a total pre-war population that was estimated to number 1,200 in 1930. It has been described as genocide.

Vietnamese conquest of Champa

The Cham and Vietnamese had a long history of conflict, with many wars ending due to economic exhaustion. It was common that the antagonists of the wars would rebuild their economies simply to go to war again. In 1471, Champa was particularly weakened prior to the Vietnamese invasion by a series of civil wars. The Vietnamese conquered Champa and settled its territory with Vietnamese migrants during the march to the south after fighting repeated wars with Champa, shattering Champa in the invasion of Champa in 1471 and finally completing the conquest in 1832 under Emperor Minh Mang. 100,000 Cham soldiers besieged a Vietnamese garrison which led to anger from Vietnam and orders to attack Champa. 30,000 Chams were captured and over 40,000 were killed.

Qing dynasty

Dzungar genocide

Some scholars estimate that about 80% of the Dzungar (Western Mongol) population (600,000 or more) was destroyed by a combination of warfare and disease in the Dzungar genocide perpetrated during the Qing conquest of the Dzungar Khanate (1755–1757). There, Manchu Bannermen and Khalkha Mongols exterminated the Dzungar Oirat Mongols. Mark Levene, a historian whose recent research interests focus on genocide, has stated that the extermination of the Dzungars was "arguably the eighteenth-century genocide par excellence".

Anti-Zunghar Uyghur rebels from the Turfan and Hami oases had submitted to Qing rule as vassals and requested Qing help for overthrowing Zunghar rule. Uyghur leaders like Emin Khoja were granted titles within the Qing nobility, and these Uyghurs helped supply the Qing military forces during the anti-Zunghar campaign. The Qing employed Khoja Emin in its campaign against the Dzungars and used him as an intermediary with Muslims from the Tarim Basin to inform them that the Qing were only aiming to kill Oirats (Zunghars) and that they would leave the Muslims alone, and also to convince them to kill the Oirats (Dzungars) themselves and side with the Qing since the Qing noted the Muslims' resentment of their former experience under Zunghar rule at the hands of Tsewang Araptan.

British Empire (pre-1945)

In places like the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, settler colonialism was carried out by the British. Foreign land viewed as attractive for settlement was declared "nobody's land". The indigenous inhabitants were therefore denied any sovereignty or property rights in the eyes of the British. This justified invasion and the violent seizure of native land to create colonies populated by British settlers. Colonization like this usually caused a large decrease in the indigenous population from war, newly introduced diseases, massacre by colonists and attempts at forced assimilation. The settlers from Britain and Europe grew rapidly in number and created entirely new societies. The indigenous population became an oppressed minority in their own country. The gradual violent expansion of colonies into indigenous land could last for centuries, as it did in the Australian frontier wars and the American Indian Wars.

Widespread population decline occurred following conquest principally from introduction of infectious disease. The number of Australian Aboriginal Australians declined by 84% after British colonization. The Maori population of New Zealand suffered a 57% drop from its highest point. In Canada, the indigenous First Nations population of British Columbia decreased by 75%. Surviving indigenous groups continued to suffer from severe racially motivated discrimination from their new colonial societies. Aboriginal children, the Stolen Generations, were confiscated by the Australian government and subject to forced assimilation and child abuse for most of the 20th century. Aboriginal Australians were only granted the right to vote in some states in 1962.

Similarly, the Canadian government has apologized for its historical "attitudes of racial and cultural superiority" and "suppression" of the first nations, including its role in residential schools where first nation children were confined and abused. Canada has been accused of genocide for its historical compulsory sterilization of indigenous peoples in Alberta during the fears of jobs being stolen by immigrants and living lives of poverty provoked by the great depression.

It has proven a controversial question whether the drastic population decline can be considered an example of genocide, and scholars have argued whether the process as a whole or specific periods and local processes qualify under the legal definition. Raphael Lemkin, the originator of the term "genocide", considered the colonial replacement of Native Americans by English and later British colonists to be one of the historical examples of genocide. Historian Niall Ferguson has referred to the case in Tasmania as follows: "In one of the most shocking of all the chapters in the history of the British Empire, the Aborigines in Van Diemen's Land were hunted down, confined and ultimately exterminated: an event which truly merits the now overused term 'genocide'.", and mentions Ireland and North America as areas that suffered ethnic cleansing at the hands of the British. According to Patrick Wolfe in the Journal of Genocide Research, the "frontier massacring of indigenous peoples" by the British constitutes a genocide.

The numerous massacres and widespread starvation that accompanied the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–1653) has led to it being called a genocide; hundreds of thousands of Irish civilians died, and about 50,000 Irish were sold into indentured servitude. As one author put it, "A loss of more than 40 per cent of the population might, however, suggest a conscious plan of elimination based on racial and religious hatred, which in other circumstances and times would rightly be called genocide. Cromwell's murderous campaign in Ireland was fuelled by a pathological hatred of Irish Catholics, which he himself clearly expressed."

The Plantations of Ireland were attempts to expel the native Irish from the best land of the island, and settle it with loyal British Protestants; they too have been described as genocidal. The Great Famine (1845–1850) has also been blamed on British policy and called genocidal. Writing in Indian Country Today, Christina Rose drew parallels between the Irish and Native American experience of dispossession and genocide; Katie Kane has compared the Sand Creek massacre with the Drogheda massacre. R. Barry O'Brien compared the Irish Rebellion of 1641 with the Indian Wars, writing "The warfare which ensued... resembled that waged by the early settlers in America with the native tribes. No mercy whatever was shown to the natives, no act of treachery was considered dishonourable, no personal tortures and indignities were spared to the captives. The slaughter of Irishmen was looked upon as literally the slaughter of wild beasts. Not only the men, but even the women and children who fell into the hands of the English were deliberately and systematically butchered. Year after year, over a great part of all Ireland, all means of human subsistence was destroyed, no quarter was given to prisoners who surrendered, and the whole population was skillfully and steadily starved to death." Similar to the European Colonization of The Americas, the death toll under the British Empire is estimated to be as high as 150 million.

Colonization of Australia

The so-called extinction of the Aboriginal Tasmanians is regarded as a classic case of near genocide by Lemkin, most comparative scholars of genocide, and many general historians, including Robert Hughes, Ward Churchill, Leo Kuper and Jared Diamond, who base their analysis on previously published histories. Between 1824 and 1908 White settlers and Native Mounted Police in Queensland, according to Raymond Evans, killed more than 10,000 Aboriginal people, who were regarded as vermin and sometimes even hunted for sport.

Prior to the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, which marked the beginning of Britain's colonization of Australia, the Aboriginal population had been estimated by historians to be around roughly 500,000 people; by 1900, that number had plummeted to fewer than 50,000. While most died due to the introduction of infectious diseases which accompanied colonization, up to 20,000 were killed during the Australian frontier wars by British settlers and colonial authorities through massacres, mass poisonings and other actions. Ben Kiernan, an Australian historian of genocide, treats the Australian evidence over the first century of colonization as an example of genocide in his 2007 history of the concept and practice, Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. The Australian practice of removing the children of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent from their families, has been described as genocidal. The 1997 report Bringing Them Home, which examined the fate of the "stolen generations" concluded that the forced separation of Aboriginal children from their family constituted an act of genocide. In the 1990s a number of Australian state institutions, including the state of Queensland, apologized for its policies regarding forcible separation of Aboriginal children. Another allegation against the Australian state is the use of medical services to Aboriginal people to administer contraceptive therapy to Aboriginal women without their knowledge or consent, including the use of Depo Provera, as well as tubal ligations. Both forced adoption and forced contraception would fall under the provisions of the UN genocide convention. Some Australian scholars, including historians Geoffrey Blainey and Keith Windschuttle and political scientist Ken Minogue, reject the view that Australian Aboriginal policy was genocidal.

Famines in British India

Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World is a book by Mike Davis about the connection between political economy and global climate patterns, particularly El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). By comparing ENSO episodes in different time periods and across countries, Davis explores the impact of colonialism and the introduction of capitalism, and the relation with famine in particular. Davis argues that "Millions died, not outside the 'modern world system', but in the very process of being forcibly incorporated into its economic and political structures. They died in the golden age of Liberal Capitalism; indeed, many were murdered... by the theological application of the sacred principles of Smith, Bentham and Mill."

Davis characterizes the Indian famines under the British Raj as "colonial genocide". Some scholars, including Niall Ferguson, have disputed this judgment, while others, including Adam Jones, have affirmed it.

Rubber Boom in Congo and Putumayo

From 1879 to 1912, the world experienced a rubber boom. Rubber prices skyrocketed, and it became increasingly profitable to extract rubber from rainforest zones in South America and Central Africa. Rubber extraction was labor-intensive, and the need for a large workforce had a significant negative effect on the indigenous population across Brazil, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia and in the Congo. The owners of the plantations or rubber barons were rich, but those who collected the rubber made very little, as a large amount of rubber was needed to be profitable. Rubber barons rounded up all the Indians and forced them to tap rubber out of the trees. Slavery and gross human rights abuses were widespread, and in some areas, 90% of the Indian population was wiped out. One plantation started with 50,000 Indians and when the killings were discovered, only 8,000 were still alive. These rubber plantations were part of the Brazilian rubber market which declined as rubber plantations in Southeast Asia became more effective.

Roger Casement, an Irishman travelling the Putumayo region of Peru as a British consul during 1910–1911, documented the abuse, slavery, murder, and use of stocks for torture against the native Indians: "The crimes charged against many men now in the employ of the Peruvian Amazon Company are of the most atrocious kind, including murder, violation, and constant flogging."

Contemporary examples

The genocide of indigenous tribes is still an ongoing feature in the modern world, with the ongoing depopulation of the Jivaro, Yanomami and other tribes in Brazil having been described as genocide. Multiple incidents of rioting against the minority communities in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and India have been documented. Paraguay has also been accused of carrying out a genocide against the Aché whose case was brought before the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. The commission gave a provisional ruling that genocide had not been committed by the state but expressed concern over "possible abuses by private persons in remote areas of the territory of Paraguay". Yazadi genocide in Iraq remains a case of major concern.

Assam, India

The Bengali speaking minority of Assam was targeted by the native people of Assam in 1983, leading to 2000 - 10,000 deaths in that year alone. Part of the larger Assam Movement and longstanding hatred of Bengali-speaking people in the region, these killings have been described as genocidal in nature. Although the people of Assam claim the Bengali-speaking people are immigrants, there has been no proof to support the claim. Discrimination against Bengali-speaking people in the region continues until present day. The Matia (Goalpara) Detention Centre was established in 2018 to capture and captivate alleged Bengali speaking immigrants in Assam. Massive crack-downs on Bengali speakers in the region have begun since then. Over 4 million Bengali speakers were threatened of being stripped of their citizenship in Assam.

Bangladesh

According to Amnesty International and Reference Services Review, the indigenous Chakma people of the Chittagong hill tracts were allegedly subjected to genocidal violence between the 1970s and the 1990s. Their population had been dwindling since the military rule launched by dictator Major General Ziaur Rahman, who took control of the country after a military coup in 1975 and reigned from 1975 to 1981. Later, his successor Lieutenant General HM Ershad who reigned from 1982 to 1990. In response, the indigenous Chakma rebels led by M.N. Larma (killed in 1983) started an insurgency in the region in 1977. The Bangladeshi government had settled hundreds of thousands of Bengali people in the region who now constitute the majority of the population there. On 11 September 1996, the indigenous rebels reportedly abducted and killed 28 to 30 Bengali woodcutters. After democracy was reestablished in the country, fresh rounds of talks began in 1996 with the newly elected prime minister Sheikh Hasina Wajed of the Awami League, the daughter of the late Father of the Nation Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the representatives of the indigenous rebels. A peace treaty was signed between the Government and the indigenous people on 2 December 1997, ending the 20 year long insurgency and all hostilities in the region.

Brazil

From the late 1950s until 1968, the state of Brazil submitted their indigenous peoples to violent attempts to integrate, pacify and acculturate their communities. In 1967, public prosecutor Jader de Figueiredo Correia submitted the Figueiredo Report to the then-ruling dictatorship. The report, which comprised seven thousand pages, was not released until 2013. It documents genocidal crimes against the indigenous peoples of Brazil, including mass murder, torture, bacteriological and chemical warfare, reported slavery, and sexual abuse. The rediscovered documents are being examined by the National Truth Commission who have been tasked with the investigations of human rights violations which occurred between 1947 and 1988. The report reveals that the Indian Protection Service (IPS) had enslaved indigenous people, tortured children, and stolen land. The Truth Commission considers that entire tribes in Maranhão were eradicated, and that in Mato Grosso an attack on thirty Cinturão Largo left only two survivors. The report also states that landowners and members of the IPS had entered isolated villages and deliberately introduced smallpox. Of the 134 people accused in the report, the state has until date not tried a single one, since the Amnesty Law passed in the end of the dictatorship does not allow trials for abuses that happened in that period. The report also details instances of mass killings, rapes, and torture, Figueiredo stated that the actions of the IPS had left indigenous peoples near extinction. The state abolished the IPS following the release of the report. The Red Cross launched an investigation after further allegations of ethnic cleansing were made after the IPS had been replaced.

China

Tibet

On 5 June 1959, Shri Purshottam Trikamdas, Senior Advocate of the Indian Supreme Court presented a report on Tibet to the International Commission of Jurists (an NGO):

From the facts stated above the following conclusions may be drawn: ... (e) To examine all such evidence obtained by this Committee and from other sources and to take appropriate action thereon and in particular to determine whether the crime of Genocide – for which already there is strong presumption – is established and, in that case, to initiate such action as envisaged by the Genocide Convention of 1948 and by the Charter of the United Nations for suppression of these acts and appropriate redress.

According to the Tibet Society of the UK, "In all, over one million Tibetans, a fifth of the population, had died as a result of the Chinese occupation right up until the end of the Cultural Revolution."

Uyghur

The Chinese government is accused of having committed a series of human rights abuses against the native Uyghur people and other ethnic and religious minorities, both inside and around the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) of the People's Republic of China, that have frequently been characterized as a genocide. Since 2014, the Chinese government, under the direction of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during the administration of CCP general secretary Xi Jinping, has pursued policies which have led to the imprisonment of more than one million Muslims (most of them Uyghurs) in secretive internment camps without any legal process in what has become the largest-scale detention of ethnic and religious minorities since World War II and The Holocaust. Critics of the policy have described it as the Sinicization of Xinjiang and they have also called it an ethnocide or a cultural genocide, and some governments, activists, independent NGOs, human rights experts, academics, government officials, independent researchers, and the East Turkistan Government-in-Exile have called it a genocide. In particular, critics have highlighted the concentration of Uyghurs in state-sponsored internment camps, the suppression of Uyghur religious practices, political indoctrination, severe ill-treatment, and extensive evidence of human rights abuses including forced sterilization, contraception, and abortion. Chinese authorities confirmed reports which state that birth rates in Xinjiang dropped by almost a third in 2018, but they denied reports of forced sterilization and genocide.

Inner Mongolia

In 1966 Mao Zedong accused the Inner Mongolian People's Party (IMPP) lead by the Mongol Ulanhu as a “political movement aiming to divide the motherland, China”. That accusation was used to eliminate the Mongol elite and to begin the genocide of the Mongols. The number of Mongol casualties during the Cultural Revolution is estimated between 16,222 (Chinese government) and 50,000 (independent study). The Office of the Inner Mongolia Communist Party Committee published statistics in 1989 which stated the total number of incarcerated Mongols were 480,000. Independent surveys overseas estimate around half a million arrested and 100,000 deaths. When including delayed deaths (returning home after imprisonment) is an estimated 300,000 casualties. The cultural revolution became ingrained among the peasantry who caused torturing, humiliation and genocide of the Mongols. Chinese propaganda teams of the CCP came from outside to Inner Mongolia and perpetrated major atrocities in the 1970s. The CCP also imposed abortions on the Mongolians.

Colombia

In the protracted conflict in Colombia, indigenous groups such as the Awá, Wayuu, Pijao and Paez people have become subjected to intense violence by right-wing paramilitaries, leftist guerrillas, and the Colombian army. Drug cartels, international resource extraction companies and the military have also used violence to force the indigenous groups out of their territories. The National Indigenous Organization of Colombia argues that the violence is genocidal in nature, but others question whether there is a "genocidal intent" as required in international law.

Congo (DRC)

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, genocidal violence against the indigenous Mbuti, Lese, and Ituri peoples has reportedly been endemic for decades. During the Congo Civil War (1998–2003), Pygmies were hunted down and eaten by both sides in the conflict, who regarded them as subhuman. Sinafasi Makelo, a representative of Mbuti pygmies, asked the UN Security Council to recognize cannibalism as a crime against humanity and an act of genocide. According to a report by Minority Rights Group International, there is evidence of mass killings, cannibalism, and rape. The report, which labeled these events as a campaign of extermination, linked much of the violence to beliefs about special powers held by the Bambuti. In the Ituri district, rebel forces ran an operation code-named "Effacer le Tableau" (to wipe the slate clean). The aim of the operation, according to witnesses, was to rid the forest of pygmies.

East Timor

Indonesia invaded East Timor or Timor-Leste, which had previously been a Portuguese colony, in 1975. Following the invasion, the Indonesian government implemented repressive military policies in an attempt to quell ethnic protests and armed resistance in the area. People from other parts of Indonesia were encouraged to settle in the region. The violence which occurred between 1975 and 1993 claimed between 120,000 and 200,000 lives. The repression entered the international spotlight in 1991 when a protest in Dili was disrupted by Indonesian forces which killed over 250 people and disappeared hundreds of others. The Santa Cruz massacre, as the event became known, drew a significant amount of international attention to the issue (it was highlighted when the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Catholic Bishop Carlos Belo and resistance leader José Ramos-Horta).

Following the international outcry, the Indonesian government began to organize a host of paramilitary groups which continued to harass and kill pro-independence activists in East Timor. At the same time, the Indonesian government significantly increased its population resettlement efforts in the area and intensified the destruction of the infrastructure and the environment used by East Timorese communities. In response to this policy, an international intervention force was eventually deployed to East Timor in order to monitor a vote for the independence of East Timor by its population in 1999. The vote was significantly in favor of independence and the Indonesian forces withdrew, but paramilitaries continued to carry out reprisal attacks for a few years. A UN Report on the Indonesian occupation identified starvation, defoliant and napalm use, torture, rape, sexual slavery, disappearances, public executions, and extrajudicial killings as sanctioned by the Indonesian government and the entire colflict. As a result, East Timorese population declined to a third of its original size of 1975.

Guatemala