Computer data storage is a technology consisting of computer components and recording media that are used to retain digital data. It is a core function and fundamental component of computers.

The central processing unit (CPU) of a computer is what manipulates data by performing computations. In practice, almost all computers use a storage hierarchy, which puts fast but expensive and small storage options close to the CPU and slower but less expensive and larger options further away. Generally, the fast technologies are referred to as "memory", while slower persistent technologies are referred to as "storage".

Even the first computer designs, Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine and Percy Ludgate's Analytical Machine, clearly distinguished between processing and memory (Babbage stored numbers as rotations of gears, while Ludgate stored numbers as displacements of rods in shuttles). This distinction was extended in the Von Neumann architecture, where the CPU consists of two main parts: The control unit and the arithmetic logic unit (ALU). The former controls the flow of data between the CPU and memory, while the latter performs arithmetic and logical operations on data.

Functionality

Without a significant amount of memory, a computer would merely be able to perform fixed operations and immediately output the result. It would have to be reconfigured to change its behavior. This is acceptable for devices such as desk calculators, digital signal processors, and other specialized devices. Von Neumann machines differ in having a memory in which they store their operating instructions and data. Such computers are more versatile in that they do not need to have their hardware reconfigured for each new program, but can simply be reprogrammed with new in-memory instructions; they also tend to be simpler to design, in that a relatively simple processor may keep state between successive computations to build up complex procedural results. Most modern computers are von Neumann machines.

Data organization and representation

A modern digital computer represents data using the binary numeral system. Text, numbers, pictures, audio, and nearly any other form of information can be converted into a string of bits, or binary digits, each of which has a value of 0 or 1. The most common unit of storage is the byte, equal to 8 bits. A piece of information can be handled by any computer or device whose storage space is large enough to accommodate the binary representation of the piece of information, or simply data. For example, the complete works of Shakespeare, about 1250 pages in print, can be stored in about five megabytes (40 million bits) with one byte per character.

Data are encoded by assigning a bit pattern to each character, digit, or multimedia object. Many standards exist for encoding (e.g. character encodings like ASCII, image encodings like JPEG, and video encodings like MPEG-4).

By adding bits to each encoded unit, redundancy allows the computer to both detect errors in coded data and correct them based on mathematical algorithms. Errors generally occur in low probabilities due to random bit value flipping, or "physical bit fatigue", loss of the physical bit in the storage of its ability to maintain a distinguishable value (0 or 1), or due to errors in inter or intra-computer communication. A random bit flip (e.g. due to random radiation) is typically corrected upon detection. A bit or a group of malfunctioning physical bits (the specific defective bit is not always known; group definition depends on the specific storage device) is typically automatically fenced out, taken out of use by the device, and replaced with another functioning equivalent group in the device, where the corrected bit values are restored (if possible). The cyclic redundancy check (CRC) method is typically used in communications and storage for error detection. A detected error is then retried.

Data compression methods allow in many cases (such as a database) to represent a string of bits by a shorter bit string ("compress") and reconstruct the original string ("decompress") when needed. This utilizes substantially less storage (tens of percents) for many types of data at the cost of more computation (compress and decompress when needed). Analysis of the trade-off between storage cost saving and costs of related computations and possible delays in data availability is done before deciding whether to keep certain data compressed or not.

For security reasons, certain types of data (e.g. credit card information) may be kept encrypted in storage to prevent the possibility of unauthorized information reconstruction from chunks of storage snapshots.

Hierarchy of storage

Generally, the lower a storage is in the hierarchy, the lesser its bandwidth and the greater its access latency is from the CPU. This traditional division of storage to primary, secondary, tertiary, and off-line storage is also guided by cost per bit.

In contemporary usage, memory is usually semiconductor storage read-write random-access memory, typically DRAM (dynamic RAM) or other forms of fast but temporary storage. Storage consists of storage devices and their media not directly accessible by the CPU (secondary or tertiary storage), typically hard disk drives, optical disc drives, and other devices slower than RAM but non-volatile (retaining contents when powered down).

Historically, memory has, depending on technology, been called central memory, core memory, core storage, drum, main memory, real storage, or internal memory. Meanwhile, slower persistent storage devices have been referred to as secondary storage, external memory, or auxiliary/peripheral storage.

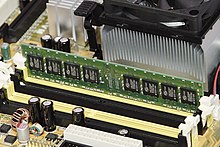

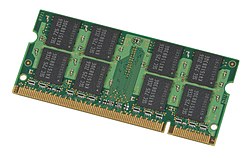

Primary storage

Primary storage (also known as main memory, internal memory, or prime memory), often referred to simply as memory, is the only one directly accessible to the CPU. The CPU continuously reads instructions stored there and executes them as required. Any data actively operated on is also stored there in uniform manner.

Historically, early computers used delay lines, Williams tubes, or rotating magnetic drums as primary storage. By 1954, those unreliable methods were mostly replaced by magnetic-core memory. Core memory remained dominant until the 1970s, when advances in integrated circuit technology allowed semiconductor memory to become economically competitive.

This led to modern random-access memory (RAM). It is small-sized, light, but quite expensive at the same time. The particular types of RAM used for primary storage are volatile, meaning that they lose the information when not powered. Besides storing opened programs, it serves as disk cache and write buffer to improve both reading and writing performance. Operating systems borrow RAM capacity for caching so long as not needed by running software. Spare memory can be utilized as RAM drive for temporary high-speed data storage.

As shown in the diagram, traditionally there are two more sub-layers of the primary storage, besides main large-capacity RAM:

- Processor registers are located inside the processor. Each register typically holds a word of data (often 32 or 64 bits). CPU instructions instruct the arithmetic logic unit to perform various calculations or other operations on this data (or with the help of it). Registers are the fastest of all forms of computer data storage.

- Processor cache is an intermediate stage between ultra-fast registers and much slower main memory. It was introduced solely to improve the performance of computers. Most actively used information in the main memory is just duplicated in the cache memory, which is faster, but of much lesser capacity. On the other hand, main memory is much slower, but has a much greater storage capacity than processor registers. Multi-level hierarchical cache setup is also commonly used—primary cache being smallest, fastest and located inside the processor; secondary cache being somewhat larger and slower.

Main memory is directly or indirectly connected to the central processing unit via a memory bus. It is actually two buses (not on the diagram): an address bus and a data bus. The CPU firstly sends a number through an address bus, a number called memory address, that indicates the desired location of data. Then it reads or writes the data in the memory cells using the data bus. Additionally, a memory management unit (MMU) is a small device between CPU and RAM recalculating the actual memory address, for example to provide an abstraction of virtual memory or other tasks.

As the RAM types used for primary storage are volatile (uninitialized at start up), a computer containing only such storage would not have a source to read instructions from, in order to start the computer. Hence, non-volatile primary storage containing a small startup program (BIOS) is used to bootstrap the computer, that is, to read a larger program from non-volatile secondary storage to RAM and start to execute it. A non-volatile technology used for this purpose is called ROM, for read-only memory (the terminology may be somewhat confusing as most ROM types are also capable of random access).

Many types of "ROM" are not literally read only, as updates to them are possible; however it is slow and memory must be erased in large portions before it can be re-written. Some embedded systems run programs directly from ROM (or similar), because such programs are rarely changed. Standard computers do not store non-rudimentary programs in ROM, and rather, use large capacities of secondary storage, which is non-volatile as well, and not as costly.

Recently, primary storage and secondary storage in some uses refer to what was historically called, respectively, secondary storage and tertiary storage.

Secondary storage

Secondary storage (also known as external memory or auxiliary storage) differs from primary storage in that it is not directly accessible by the CPU. The computer usually uses its input/output channels to access secondary storage and transfer the desired data to primary storage. Secondary storage is non-volatile (retaining data when its power is shut off). Modern computer systems typically have two orders of magnitude more secondary storage than primary storage because secondary storage is less expensive.

In modern computers, hard disk drives (HDDs) or solid-state drives (SSDs) are usually used as secondary storage. The access time per byte for HDDs or SSDs is typically measured in milliseconds (thousandths of a second), while the access time per byte for primary storage is measured in nanoseconds (billionths of a second). Thus, secondary storage is significantly slower than primary storage. Rotating optical storage devices, such as CD and DVD drives, have even longer access times. Other examples of secondary storage technologies include USB flash drives, floppy disks, magnetic tape, paper tape, punched cards, and RAM disks.

Once the disk read/write head on HDDs reaches the proper placement and the data, subsequent data on the track are very fast to access. To reduce the seek time and rotational latency, data are transferred to and from disks in large contiguous blocks. Sequential or block access on disks is orders of magnitude faster than random access, and many sophisticated paradigms have been developed to design efficient algorithms based upon sequential and block access. Another way to reduce the I/O bottleneck is to use multiple disks in parallel in order to increase the bandwidth between primary and secondary memory.[5]

Secondary storage is often formatted according to a file system format, which provides the abstraction necessary to organize data into files and directories, while also providing metadata describing the owner of a certain file, the access time, the access permissions, and other information.

Most computer operating systems use the concept of virtual memory, allowing utilization of more primary storage capacity than is physically available in the system. As the primary memory fills up, the system moves the least-used chunks (pages) to a swap file or page file on secondary storage, retrieving them later when needed. If a lot of pages are moved to slower secondary storage, the system performance is degraded.

Tertiary storage

Tertiary storage or tertiary memory is a level below secondary storage. Typically, it involves a robotic mechanism which will mount (insert) and dismount removable mass storage media into a storage device according to the system's demands; such data are often copied to secondary storage before use. It is primarily used for archiving rarely accessed information since it is much slower than secondary storage (e.g. 5–60 seconds vs. 1–10 milliseconds). This is primarily useful for extraordinarily large data stores, accessed without human operators. Typical examples include tape libraries and optical jukeboxes.

When a computer needs to read information from the tertiary storage, it will first consult a catalog database to determine which tape or disc contains the information. Next, the computer will instruct a robotic arm to fetch the medium and place it in a drive. When the computer has finished reading the information, the robotic arm will return the medium to its place in the library.

Tertiary storage is also known as nearline storage because it is "near to online". The formal distinction between online, nearline, and offline storage is:

- Online storage is immediately available for I/O.

- Nearline storage is not immediately available, but can be made online quickly without human intervention.

- Offline storage is not immediately available, and requires some human intervention to become online.

For example, always-on spinning hard disk drives are online storage, while spinning drives that spin down automatically, such as in massive arrays of idle disks (MAID), are nearline storage. Removable media such as tape cartridges that can be automatically loaded, as in tape libraries, are nearline storage, while tape cartridges that must be manually loaded are offline storage.

Off-line storage

Off-line storage is a computer data storage on a medium or a device that is not under the control of a processing unit. The medium is recorded, usually in a secondary or tertiary storage device, and then physically removed or disconnected. It must be inserted or connected by a human operator before a computer can access it again. Unlike tertiary storage, it cannot be accessed without human interaction.

Off-line storage is used to transfer information, since the detached medium can easily be physically transported. Additionally, it is useful for cases of disaster, where, for example, a fire destroys the original data, a medium in a remote location will be unaffected, enabling disaster recovery. Off-line storage increases general information security, since it is physically inaccessible from a computer, and data confidentiality or integrity cannot be affected by computer-based attack techniques. Also, if the information stored for archival purposes is rarely accessed, off-line storage is less expensive than tertiary storage.

In modern personal computers, most secondary and tertiary storage media are also used for off-line storage. Optical discs and flash memory devices are the most popular, and to a much lesser extent removable hard disk drives. In enterprise uses, magnetic tape is predominant. Older examples are floppy disks, Zip disks, or punched cards.

Characteristics of storage

Storage technologies at all levels of the storage hierarchy can be differentiated by evaluating certain core characteristics as well as measuring characteristics specific to a particular implementation. These core characteristics are volatility, mutability, accessibility, and addressability. For any particular implementation of any storage technology, the characteristics worth measuring are capacity and performance.

| Characteristic | Hard disk drive | Optical disc | Flash memory | Random-access memory | Linear tape-open |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Magnetic disk | Laser beam | Semiconductor | Magnetic tape | |

| Volatility | No | No | No | Volatile | No |

| Random access | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Latency (access time) | ~15 ms (swift) | ~150 ms (moderate) | None (instant) | None (instant) | Lack of random access (very slow) |

| Controller | Internal | External | Internal | Internal | External |

| Failure with imminent data loss | Head crash | — | Circuitry | — | |

| Error detection | Diagnostic (S.M.A.R.T.) | Error rate measurement | Indicated by downward spikes in transfer rates | (Short-term storage) | Unknown |

| Price per space | Low | Low | High | Very high | Very low (but expensive drives) |

| Price per unit | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate (but expensive drives) |

| Main application | Mid-term archival, routine backups, server, workstation storage expansion | Long-term archival, hard copy distribution | Portable electronics; operating system | Real-time | Long-term archival |

Volatility

Non-volatile memory retains the stored information even if not constantly supplied with electric power. It is suitable for long-term storage of information. Volatile memory requires constant power to maintain the stored information. The fastest memory technologies are volatile ones, although that is not a universal rule. Since the primary storage is required to be very fast, it predominantly uses volatile memory.

Dynamic random-access memory is a form of volatile memory that also requires the stored information to be periodically reread and rewritten, or refreshed, otherwise it would vanish. Static random-access memory is a form of volatile memory similar to DRAM with the exception that it never needs to be refreshed as long as power is applied; it loses its content when the power supply is lost.

An uninterruptible power supply (UPS) can be used to give a computer a brief window of time to move information from primary volatile storage into non-volatile storage before the batteries are exhausted. Some systems, for example EMC Symmetrix, have integrated batteries that maintain volatile storage for several minutes.

Mutability

- Read/write storage or mutable storage

- Allows information to be overwritten at any time. A computer without some amount of read/write storage for primary storage purposes would be useless for many tasks. Modern computers typically use read/write storage also for secondary storage.

- Slow write, fast read storage

- Read/write storage which allows information to be overwritten multiple times, but with the write operation being much slower than the read operation. Examples include CD-RW and SSD.

- Write once storage

- Write once read many (WORM) allows the information to be written only once at some point after manufacture. Examples include semiconductor programmable read-only memory and CD-R.

- Read only storage

- Retains the information stored at the time of manufacture. Examples include mask ROM ICs and CD-ROM.

Accessibility

- Random access

- Any location in storage can be accessed at any moment in approximately the same amount of time. Such characteristic is well suited for primary and secondary storage. Most semiconductor memories, flash memories and hard disk drives provide random access, though both semiconductor and flash memories have minimal latency when compared to hard disk drives, as no mechanical parts need to be moved.

- Sequential access

- The accessing of pieces of information will be in a serial order, one after the other; therefore the time to access a particular piece of information depends upon which piece of information was last accessed. Such characteristic is typical of off-line storage.

Addressability

- Location-addressable

- Each individually accessible unit of information in storage is selected with its numerical memory address. In modern computers, location-addressable storage usually limits to primary storage, accessed internally by computer programs, since location-addressability is very efficient, but burdensome for humans.

- File addressable

- Information is divided into files of variable length, and a particular file is selected with human-readable directory and file names. The underlying device is still location-addressable, but the operating system of a computer provides the file system abstraction to make the operation more understandable. In modern computers, secondary, tertiary and off-line storage use file systems.

- Content-addressable

- Each individually accessible unit of information is selected based on the basis of (part of) the contents stored there. Content-addressable storage can be implemented using software (computer program) or hardware (computer device), with hardware being faster but more expensive option. Hardware content addressable memory is often used in a computer's CPU cache.

Capacity

- Raw capacity

- The total amount of stored information that a storage device or medium can hold. It is expressed as a quantity of bits or bytes (e.g. 10.4 megabytes).

- Memory storage density

- The compactness of stored information. It is the storage capacity of a medium divided with a unit of length, area or volume (e.g. 1.2 megabytes per square inch).

Performance

- Latency

- The time it takes to access a particular location in storage. The relevant unit of measurement is typically nanosecond for primary storage, millisecond for secondary storage, and second for tertiary storage. It may make sense to separate read latency and write latency (especially for non-volatile memory) and in case of sequential access storage, minimum, maximum and average latency.

- Throughput

- The rate at which information can be read from or written to the storage. In computer data storage, throughput is usually expressed in terms of megabytes per second (MB/s), though bit rate may also be used. As with latency, read rate and write rate may need to be differentiated. Also accessing media sequentially, as opposed to randomly, typically yields maximum throughput.

- Granularity

- The size of the largest "chunk" of data that can be efficiently accessed as a single unit, e.g. without introducing additional latency.

- Reliability

- The probability of spontaneous bit value change under various conditions, or overall failure rate.

Utilities such as hdparm and sar can be used to measure IO performance in Linux.

Energy use

- Storage devices that reduce fan usage automatically shut-down during inactivity, and low power hard drives can reduce energy consumption by 90 percent.

- 2.5-inch hard disk drives often consume less power than larger ones. Low capacity solid-state drives have no moving parts and consume less power than hard disks. Also, memory may use more power than hard disks. Large caches, which are used to avoid hitting the memory wall, may also consume a large amount of power.

Security

Full disk encryption, volume and virtual disk encryption, andor file/folder encryption is readily available for most storage devices.

Hardware memory encryption is available in Intel Architecture, supporting Total Memory Encryption (TME) and page granular memory encryption with multiple keys (MKTME).[17][18] and in SPARC M7 generation since October 2015.

Vulnerability and reliability

Distinct types of data storage have different points of failure and various methods of predictive failure analysis.

Vulnerabilities that can instantly lead to total loss are head crashing on mechanical hard drives and failure of electronic components on flash storage.

Error detection

Impending failure on hard disk drives is estimable using S.M.A.R.T. diagnostic data that includes the hours of operation and the count of spin-ups, though its reliability is disputed.

Flash storage may experience downspiking transfer rates as a result of accumulating errors, which the flash memory controller attempts to correct.

The health of optical media can be determined by measuring correctable minor errors, of which high counts signify deteriorating and/or low-quality media. Too many consecutive minor errors can lead to data corruption. Not all vendors and models of optical drives support error scanning.

Storage media

As of 2011, the most commonly used data storage media are semiconductor, magnetic, and optical, while paper still sees some limited usage. Some other fundamental storage technologies, such as all-flash arrays (AFAs) are proposed for development.

Semiconductor

Semiconductor memory uses semiconductor-based integrated circuit (IC) chips to store information. Data are typically stored in metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) memory cells. A semiconductor memory chip may contain millions of memory cells, consisting of tiny MOS field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) and/or MOS capacitors. Both volatile and non-volatile forms of semiconductor memory exist, the former using standard MOSFETs and the latter using floating-gate MOSFETs.

In modern computers, primary storage almost exclusively consists of dynamic volatile semiconductor random-access memory (RAM), particularly dynamic random-access memory (DRAM). Since the turn of the century, a type of non-volatile floating-gate semiconductor memory known as flash memory has steadily gained share as off-line storage for home computers. Non-volatile semiconductor memory is also used for secondary storage in various advanced electronic devices and specialized computers that are designed for them.

As early as 2006, notebook and desktop computer manufacturers started using flash-based solid-state drives (SSDs) as default configuration options for the secondary storage either in addition to or instead of the more traditional HDD.

Magnetic

Magnetic storage uses different patterns of magnetization on a magnetically coated surface to store information. Magnetic storage is non-volatile. The information is accessed using one or more read/write heads which may contain one or more recording transducers. A read/write head only covers a part of the surface so that the head or medium or both must be moved relative to another in order to access data. In modern computers, magnetic storage will take these forms:

- Magnetic disk;

- Floppy disk, used for off-line storage;

- Hard disk drive, used for secondary storage.

- Magnetic tape, used for tertiary and off-line storage;

- Carousel memory (magnetic rolls).

In early computers, magnetic storage was also used as:

- Primary storage in a form of magnetic memory, or core memory, core rope memory, thin-film memory and/or twistor memory;

- Tertiary (e.g. NCR CRAM) or off line storage in the form of magnetic cards;

- Magnetic tape was then often used for secondary storage.

Magnetic storage does not have a definite limit of rewriting cycles like flash storage and re-writeable optical media, as altering magnetic fields causes no physical wear. Rather, their life span is limited by mechanical parts.

Optical

Optical storage, the typical optical disc, stores information in deformities on the surface of a circular disc and reads this information by illuminating the surface with a laser diode and observing the reflection. Optical disc storage is non-volatile. The deformities may be permanent (read only media), formed once (write once media) or reversible (recordable or read/write media). The following forms are currently in common use:

- CD, CD-ROM, DVD, BD-ROM: Read only storage, used for mass distribution of digital information (music, video, computer programs);

- CD-R, DVD-R, DVD+R, BD-R: Write once storage, used for tertiary and off-line storage;

- CD-RW, DVD-RW, DVD+RW, DVD-RAM, BD-RE: Slow write, fast read storage, used for tertiary and off-line storage;

- Ultra Density Optical or UDO is similar in capacity to BD-R or BD-RE and is slow write, fast read storage used for tertiary and off-line storage.

Magneto-optical disc storage is optical disc storage where the magnetic state on a ferromagnetic surface stores information. The information is read optically and written by combining magnetic and optical methods. Magneto-optical disc storage is non-volatile, sequential access, slow write, fast read storage used for tertiary and off-line storage.

3D optical data storage has also been proposed.

Light induced magnetization melting in magnetic photoconductors has also been proposed for high-speed low-energy consumption magneto-optical storage.

Paper

Paper data storage, typically in the form of paper tape or punched cards, has long been used to store information for automatic processing, particularly before general-purpose computers existed. Information was recorded by punching holes into the paper or cardboard medium and was read mechanically (or later optically) to determine whether a particular location on the medium was solid or contained a hole. Barcodes make it possible for objects that are sold or transported to have some computer-readable information securely attached.

Relatively small amounts of digital data (compared to other digital data storage) may be backed up on paper as a matrix barcode for very long-term storage, as the longevity of paper typically exceeds even magnetic data storage.

Other storage media or substrates

- Vacuum-tube memory

- A Williams tube used a cathode-ray tube, and a Selectron tube used a large vacuum tube to store information. These primary storage devices were short-lived in the market, since the Williams tube was unreliable, and the Selectron tube was expensive.

- Electro-acoustic memory

- Delay-line memory used sound waves in a substance such as mercury to store information. Delay-line memory was dynamic volatile, cycle sequential read/write storage, and was used for primary storage.

- Optical tape

- is a medium for optical storage, generally consisting of a long and narrow strip of plastic, onto which patterns can be written and from which the patterns can be read back. It shares some technologies with cinema film stock and optical discs, but is compatible with neither. The motivation behind developing this technology was the possibility of far greater storage capacities than either magnetic tape or optical discs.

- Phase-change memory

- uses different mechanical phases of phase-change material to store information in an X–Y addressable matrix and reads the information by observing the varying electrical resistance of the material. Phase-change memory would be non-volatile, random-access read/write storage, and might be used for primary, secondary and off-line storage. Most rewritable and many write-once optical disks already use phase-change material to store information.

- Holographic data storage

- stores information optically inside crystals or photopolymers. Holographic storage can utilize the whole volume of the storage medium, unlike optical disc storage, which is limited to a small number of surface layers. Holographic storage would be non-volatile, sequential-access, and either write-once or read/write storage. It might be used for secondary and off-line storage. See Holographic Versatile Disc (HVD).

- Molecular memory

- stores information in polymer that can store electric charge. Molecular memory might be especially suited for primary storage. The theoretical storage capacity of molecular memory is 10 terabits per square inch (16 Gbit/mm2).

- Magnetic photoconductors

- store magnetic information, which can be modified by low-light illumination.

- DNA

- stores information in DNA nucleotides. It was first done in 2012, when researchers achieved a ratio of 1.28 petabytes per gram of DNA. In March 2017 scientists reported that a new algorithm called a DNA fountain achieved 85% of the theoretical limit, at 215 petabytes per gram of DNA.

Related technologies

Redundancy

While a group of bits malfunction may be resolved by error detection and correction mechanisms (see above), storage device malfunction requires different solutions. The following solutions are commonly used and valid for most storage devices:

- Device mirroring (replication) – A common solution to the problem is constantly maintaining an identical copy of device content on another device (typically of a same type). The downside is that this doubles the storage, and both devices (copies) need to be updated simultaneously with some overhead and possibly some delays. The upside is possible concurrent read of a same data group by two independent processes, which increases performance. When one of the replicated devices is detected to be defective, the other copy is still operational, and is being utilized to generate a new copy on another device (usually available operational in a pool of stand-by devices for this purpose).

- Redundant array of independent disks (RAID) – This method generalizes the device mirroring above by allowing one device in a group of ndevices to fail and be replaced with the content restored (Device mirroring is RAID with n=2). RAID groups of n=5 or n=6 are common. n>2 saves storage, when comparing with n=2, at the cost of more processing during both regular operation (with often reduced performance) and defective device replacement.

Device mirroring and typical RAID are designed to handle a single device failure in the RAID group of devices. However, if a second failure occurs before the RAID group is completely repaired from the first failure, then data can be lost. The probability of a single failure is typically small. Thus the probability of two failures in a same RAID group in time proximity is much smaller (approximately the probability squared, i.e., multiplied by itself). If a database cannot tolerate even such smaller probability of data loss, then the RAID group itself is replicated (mirrored). In many cases such mirroring is done geographically remotely, in a different storage array, to handle also recovery from disasters (see disaster recovery above).

Network connectivity

A secondary or tertiary storage may connect to a computer utilizing computer networks. This concept does not pertain to the primary storage, which is shared between multiple processors to a lesser degree.

- Direct-attached storage (DAS) is a traditional mass storage, that does not use any network. This is still a most popular approach. This retronym was coined recently, together with NAS and SAN.

- Network-attached storage (NAS) is mass storage attached to a computer which another computer can access at file level over a local area network, a private wide area network, or in the case of online file storage, over the Internet. NAS is commonly associated with the NFS and CIFS/SMB protocols.

- Storage area network (SAN) is a specialized network, that provides other computers with storage capacity. The crucial difference between NAS and SAN, is that NAS presents and manages file systems to client computers, while SAN provides access at block-addressing (raw) level, leaving it to attaching systems to manage data or file systems within the provided capacity. SAN is commonly associated with Fibre Channel networks.

Robotic storage

Large quantities of individual magnetic tapes, and optical or magneto-optical discs may be stored in robotic tertiary storage devices. In tape storage field they are known as tape libraries, and in optical storage field optical jukeboxes, or optical disk libraries per analogy. The smallest forms of either technology containing just one drive device are referred to as autoloaders or autochangers.

Robotic-access storage devices may have a number of slots, each holding individual media, and usually one or more picking robots that traverse the slots and load media to built-in drives. The arrangement of the slots and picking devices affects performance. Important characteristics of such storage are possible expansion options: adding slots, modules, drives, robots. Tape libraries may have from 10 to more than 100,000 slots, and provide terabytes or petabytes of near-line information. Optical jukeboxes are somewhat smaller solutions, up to 1,000 slots.

Robotic storage is used for backups, and for high-capacity archives in imaging, medical, and video industries. Hierarchical storage management is a most known archiving strategy of automatically migrating long-unused files from fast hard disk storage to libraries or jukeboxes. If the files are needed, they are retrieved back to disk.