In computing, a file system or filesystem (often abbreviated to fs) is a method and data structure that the operating system uses to control how data are stored and retrieved. Without a file system, data placed in a storage medium would be one large body of data with no way to tell where one piece of data stopped and the next began, or where any piece of data was located when it was time to retrieve it. By separating the data into pieces and giving each piece a name, the data are easily isolated and identified. Taking its name from the way a paper-based data management system is named, each group of data is called a "file". The structure and logic rules used to manage the groups of data and their names is called a "file system."

There are many kinds of file systems, each with unique structure and logic, properties of speed, flexibility, security, size and more. Some file systems have been designed to be used for specific applications. For example, the ISO 9660 and UDF file systems are designed specifically for optical discs.

File systems can be used on many types of storage devices using various media. As of 2019, hard disk drives have been key storage devices and are projected to remain so for the foreseeable future. Other kinds of media that are used include SSDs, magnetic tapes, and optical discs. In some cases, such as with tmpfs, the computer's main memory (random-access memory, RAM) is used to create a temporary file system for short-term use.

Some file systems are used on local data storage devices; others provide file access via a network protocol (for example, NFS, SMB, or 9P clients). Some file systems are "virtual", meaning that the supplied "files" (called virtual files) are computed on request (such as procfs and sysfs) or are merely a mapping into a different file system used as a backing store. The file system manages access to both the content of files and the metadata about those files. It is responsible for arranging storage space; reliability, efficiency, and tuning with regard to the physical storage medium are important design considerations.

Origin of the term

From c.1900 and before the advent of computers the terms file system and system for filing were used to describe a method of storing and retrieving paper documents. By 1961, the term file system was being applied to computerized filing alongside the original meaning. By 1964, it was in general use.

Architecture

A file system consists of two or three layers. Sometimes the layers are explicitly separated, and sometimes the functions are combined.

The logical file system is responsible for interaction with the user application. It provides the application program interface (API) for file operations — OPEN, CLOSE, READ,

etc., and passes the requested operation to the layer below it for

processing. The logical file system "manage[s] open file table entries

and per-process file descriptors". This layer provides "file access, directory operations, [and] security and protection".

The second optional layer is the virtual file system. "This interface allows support for multiple concurrent instances of physical file systems, each of which is called a file system implementation".

The third layer is the physical file system. This layer is concerned with the physical operation of the storage device (e.g. disk). It processes physical blocks being read or written. It handles buffering and memory management and is responsible for the physical placement of blocks in specific locations on the storage medium. The physical file system interacts with the device drivers or with the channel to drive the storage device.

Aspects of file systems

Space management

Note: this only applies to file systems used in storage devices.

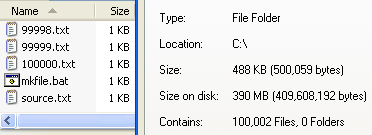

File systems allocate space in a granular manner, usually multiple physical units on the device. The file system is responsible for organizing files and directories, and keeping track of which areas of the media belong to which file and which are not being used. For example, in Apple DOS of the early 1980s, 256-byte sectors on 140 kilobyte floppy disk used a track/sector map.

This results in unused space when a file is not an exact multiple of the allocation unit, sometimes referred to as slack space. For a 512-byte allocation, the average unused space is 256 bytes. For 64 KB clusters, the average unused space is 32 KB. The size of the allocation unit is chosen when the file system is created. Choosing the allocation size based on the average size of the files expected to be in the file system can minimize the amount of unusable space. Frequently the default allocation may provide reasonable usage. Choosing an allocation size that is too small results in excessive overhead if the file system will contain mostly very large files.

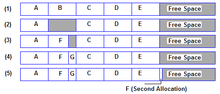

File system fragmentation occurs when unused space or single files are not contiguous. As a file system is used, files are created, modified and deleted. When a file is created, the file system allocates space for the data. Some file systems permit or require specifying an initial space allocation and subsequent incremental allocations as the file grows. As files are deleted, the space they were allocated eventually is considered available for use by other files. This creates alternating used and unused areas of various sizes. This is free space fragmentation. When a file is created and there is not an area of contiguous space available for its initial allocation, the space must be assigned in fragments. When a file is modified such that it becomes larger, it may exceed the space initially allocated to it, another allocation must be assigned elsewhere and the file becomes fragmented.

In some operating systems, a system administrator may use disk quotas to limit the allocation of disk space.

Filenames

A filename (or file name) is used to identify a storage

location in the file system. Most file systems have restrictions on the

length of filenames. In some file systems, filenames are not case sensitive (i.e., the names MYFILE and myfile refer to the same file in a directory); in others, filenames are case sensitive (i.e., the names MYFILE, MyFile, and myfile refer to three separate files that are in the same directory).

Most modern file systems allow filenames to contain a wide range of characters from the Unicode character set. However, they may have restrictions on the use of certain special characters, disallowing them within filenames; those characters might be used to indicate a device, device type, directory prefix, file path separator, or file type.

Directories

File systems typically have directories (also called folders) which allow the user to group files into separate collections. This may be implemented by associating the file name with an index in a table of contents or an inode in a Unix-like file system. Directory structures may be flat (i.e. linear), or allow hierarchies where directories may contain subdirectories. The first file system to support arbitrary hierarchies of directories was used in the Multics operating system. The native file systems of Unix-like systems also support arbitrary directory hierarchies, as do, for example, Apple's Hierarchical File System and its successor HFS+ in classic Mac OS, the FAT file system in MS-DOS 2.0 and later versions of MS-DOS and in Microsoft Windows, the NTFS file system in the Windows NT family of operating systems, and the ODS-2 (On-Disk Structure-2) and higher levels of the Files-11 file system in OpenVMS.

Metadata

Other bookkeeping information is typically associated with each file within a file system. The length of the data contained in a file may be stored as the number of blocks allocated for the file or as a byte count. The time that the file was last modified may be stored as the file's timestamp. File systems might store the file creation time, the time it was last accessed, the time the file's metadata was changed, or the time the file was last backed up. Other information can include the file's device type (e.g. block, character, socket, subdirectory, etc.), its owner user ID and group ID, its access permissions and other file attributes (e.g. whether the file is read-only, executable, etc.).

A file system stores all the metadata associated with the file—including the file name, the length of the contents of a file, and the location of the file in the folder hierarchy—separate from the contents of the file.

Most file systems store the names of all the files in one directory in one place—the directory table for that directory—which is often stored like any other file. Many file systems put only some of the metadata for a file in the directory table, and the rest of the metadata for that file in a completely separate structure, such as the inode.

Most file systems also store metadata not associated with any one particular file. Such metadata includes information about unused regions—free space bitmap, block availability map—and information about bad sectors. Often such information about an allocation group is stored inside the allocation group itself.

Additional attributes can be associated on file systems, such as NTFS, XFS, ext2, ext3, some versions of UFS, and HFS+, using extended file attributes. Some file systems provide for user defined attributes such as the author of the document, the character encoding of a document or the size of an image.

Some file systems allow for different data collections to be associated with one file name. These separate collections may be referred to as streams or forks. Apple has long used a forked file system on the Macintosh, and Microsoft supports streams in NTFS. Some file systems maintain multiple past revisions of a file under a single file name; the filename by itself retrieves the most recent version, while prior saved version can be accessed using a special naming convention such as "filename;4" or "filename(-4)" to access the version four saves ago.

See comparison of file systems#Metadata for details on which file systems support which kinds of metadata.

File system as an abstract user interface

In some cases, a file system may not make use of a storage device but can be used to organize and represent access to any data, whether it is stored or dynamically generated (e.g. procfs).

Utilities

File systems include utilities to initialize, alter parameters of and remove an instance of the file system. Some include the ability to extend or truncate the space allocated to the file system.

Directory utilities may be used to create, rename and delete directory entries, which are also known as dentries (singular: dentry), and to alter metadata associated with a directory. Directory utilities may also include capabilities to create additional links to a directory (hard links in Unix), to rename parent links (".." in Unix-like operating systems), and to create bidirectional links to files.

File utilities create, list, copy, move and delete files, and alter metadata. They may be able to truncate data, truncate or extend space allocation, append to, move, and modify files in-place. Depending on the underlying structure of the file system, they may provide a mechanism to prepend to or truncate from the beginning of a file, insert entries into the middle of a file, or delete entries from a file. Utilities to free space for deleted files, if the file system provides an undelete function, also belong to this category.

Some file systems defer operations such as reorganization of free space, secure erasing of free space, and rebuilding of hierarchical structures by providing utilities to perform these functions at times of minimal activity. An example is the file system defragmentation utilities.

Some of the most important features of file system utilities are supervisory activities which may involve bypassing ownership or direct access to the underlying device. These include high-performance backup and recovery, data replication, and reorganization of various data structures and allocation tables within the file system.

Restricting and permitting access

There are several mechanisms used by file systems to control access to data. Usually the intent is to prevent reading or modifying files by a user or group of users. Another reason is to ensure data is modified in a controlled way so access may be restricted to a specific program. Examples include passwords stored in the metadata of the file or elsewhere and file permissions in the form of permission bits, access control lists, or capabilities. The need for file system utilities to be able to access the data at the media level to reorganize the structures and provide efficient backup usually means that these are only effective for polite users but are not effective against intruders.

Methods for encrypting file data are sometimes included in the file system. This is very effective since there is no need for file system utilities to know the encryption seed to effectively manage the data. The risks of relying on encryption include the fact that an attacker can copy the data and use brute force to decrypt the data. Additionally, losing the seed means losing the data.

Maintaining integrity

One significant responsibility of a file system is to ensure that the file system structures in secondary storage remain consistent, regardless of the actions by programs accessing the file system. This includes actions taken if a program modifying the file system terminates abnormally or neglects to inform the file system that it has completed its activities. This may include updating the metadata, the directory entry and handling any data that was buffered but not yet updated on the physical storage media.

Other failures which the file system must deal with include media failures or loss of connection to remote systems.

In the event of an operating system failure or "soft" power failure, special routines in the file system must be invoked similar to when an individual program fails.

The file system must also be able to correct damaged structures. These may occur as a result of an operating system failure for which the OS was unable to notify the file system, a power failure, or a reset.

The file system must also record events to allow analysis of systemic issues as well as problems with specific files or directories.

User data

The most important purpose of a file system is to manage user data. This includes storing, retrieving and updating data.

Some file systems accept data for storage as a stream of bytes which are collected and stored in a manner efficient for the media. When a program retrieves the data, it specifies the size of a memory buffer and the file system transfers data from the media to the buffer. A runtime library routine may sometimes allow the user program to define a record based on a library call specifying a length. When the user program reads the data, the library retrieves data via the file system and returns a record.

Some file systems allow the specification of a fixed record length which is used for all writes and reads. This facilitates locating the nth record as well as updating records.

An identification for each record, also known as a key, makes for a more sophisticated file system. The user program can read, write and update records without regard to their location. This requires complicated management of blocks of media usually separating key blocks and data blocks. Very efficient algorithms can be developed with pyramid structures for locating records.

Using a file system

Utilities, language specific run-time libraries and user programs use file system APIs to make requests of the file system. These include data transfer, positioning, updating metadata, managing directories, managing access specifications, and removal.

Multiple file systems within a single system

Frequently, retail systems are configured with a single file system occupying the entire storage device.

Another approach is to partition the disk so that several file systems with different attributes can be used. One file system, for use as browser cache or email storage, might be configured with a small allocation size. This keeps the activity of creating and deleting files typical of browser activity in a narrow area of the disk where it will not interfere with other file allocations. Another partition might be created for the storage of audio or video files with a relatively large block size. Yet another may normally be set read-only and only periodically be set writable.

A third approach, which is mostly used in cloud systems, is to use "disk images" to house additional file systems, with the same attributes or not, within another (host) file system as a file. A common example is virtualization: one user can run an experimental Linux distribution (using the ext4 file system) in a virtual machine under his/her production Windows environment (using NTFS). The ext4 file system resides in a disk image, which is treated as a file (or multiple files, depending on the hypervisor and settings) in the NTFS host file system.

Having multiple file systems on a single system has the additional benefit that in the event of a corruption of a single partition, the remaining file systems will frequently still be intact. This includes virus destruction of the system partition or even a system that will not boot. File system utilities which require dedicated access can be effectively completed piecemeal. In addition, defragmentation may be more effective. Several system maintenance utilities, such as virus scans and backups, can also be processed in segments. For example, it is not necessary to backup the file system containing videos along with all the other files if none have been added since the last backup. As for the image files, one can easily "spin off" differential images which contain only "new" data written to the master (original) image. Differential images can be used for both safety concerns (as a "disposable" system - can be quickly restored if destroyed or contaminated by a virus, as the old image can be removed and a new image can be created in matter of seconds, even without automated procedures) and quick virtual machine deployment (since the differential images can be quickly spawned using a script in batches).

Design limitations

All file systems have some functional limit that defines the maximum storable data capacity within that system. These functional limits are a best-guess effort by the designer based on how large the storage systems are right now and how large storage systems are likely to become in the future. Disk storage has continued to increase at near exponential rates (see Moore's law), so after a few years, file systems have kept reaching design limitations that require computer users to repeatedly move to a newer system with ever-greater capacity.

File system complexity typically varies proportionally with the available storage capacity. The file systems of early 1980s home computers with 50 KB to 512 KB of storage would not be a reasonable choice for modern storage systems with hundreds of gigabytes of capacity. Likewise, modern file systems would not be a reasonable choice for these early systems, since the complexity of modern file system structures would quickly consume or even exceed the very limited capacity of the early storage systems.

Types of file systems

File system types can be classified into disk/tape file systems, network file systems and special-purpose file systems.

Disk file systems

A disk file system takes advantages of the ability of disk storage media to randomly address data in a short amount of time. Additional considerations include the speed of accessing data following that initially requested and the anticipation that the following data may also be requested. This permits multiple users (or processes) access to various data on the disk without regard to the sequential location of the data. Examples include FAT (FAT12, FAT16, FAT32), exFAT, NTFS, ReFS, HFS and HFS+, HPFS, APFS, UFS, ext2, ext3, ext4, XFS, btrfs, Files-11, Veritas File System, VMFS, ZFS, ReiserFS, NSS and ScoutFS. Some disk file systems are journaling file systems or versioning file systems.

Optical discs

ISO 9660 and Universal Disk Format (UDF) are two common formats that target Compact Discs, DVDs and Blu-ray discs. Mount Rainier is an extension to UDF supported since 2.6 series of the Linux kernel and since Windows Vista that facilitates rewriting to DVDs.

Flash file systems

A flash file system considers the special abilities, performance and restrictions of flash memory devices. Frequently a disk file system can use a flash memory device as the underlying storage media, but it is much better to use a file system specifically designed for a flash device.

Tape file systems

A tape file system is a file system and tape format designed to store files on tape. Magnetic tapes are sequential storage media with significantly longer random data access times than disks, posing challenges to the creation and efficient management of a general-purpose file system.

In a disk file system there is typically a master file directory, and a map of used and free data regions. Any file additions, changes, or removals require updating the directory and the used/free maps. Random access to data regions is measured in milliseconds so this system works well for disks.

Tape requires linear motion to wind and unwind potentially very long reels of media. This tape motion may take several seconds to several minutes to move the read/write head from one end of the tape to the other.

Consequently, a master file directory and usage map can be extremely slow and inefficient with tape. Writing typically involves reading the block usage map to find free blocks for writing, updating the usage map and directory to add the data, and then advancing the tape to write the data in the correct spot. Each additional file write requires updating the map and directory and writing the data, which may take several seconds to occur for each file.

Tape file systems instead typically allow for the file directory to be spread across the tape intermixed with the data, referred to as streaming, so that time-consuming and repeated tape motions are not required to write new data.

However, a side effect of this design is that reading the file directory of a tape usually requires scanning the entire tape to read all the scattered directory entries. Most data archiving software that works with tape storage will store a local copy of the tape catalog on a disk file system, so that adding files to a tape can be done quickly without having to rescan the tape media. The local tape catalog copy is usually discarded if not used for a specified period of time, at which point the tape must be re-scanned if it is to be used in the future.

IBM has developed a file system for tape called the Linear Tape File System. The IBM implementation of this file system has been released as the open-source IBM Linear Tape File System — Single Drive Edition (LTFS-SDE) product. The Linear Tape File System uses a separate partition on the tape to record the index meta-data, thereby avoiding the problems associated with scattering directory entries across the entire tape.

Tape formatting

Writing data to a tape, erasing, or formatting a tape is often a significantly time-consuming process and can take several hours on large tapes. With many data tape technologies it is not necessary to format the tape before over-writing new data to the tape. This is due to the inherently destructive nature of overwriting data on sequential media.

Because of the time it can take to format a tape, typically tapes are pre-formatted so that the tape user does not need to spend time preparing each new tape for use. All that is usually necessary is to write an identifying media label to the tape before use, and even this can be automatically written by software when a new tape is used for the first time.

Database file systems

Another concept for file management is the idea of a database-based file system. Instead of, or in addition to, hierarchical structured management, files are identified by their characteristics, like type of file, topic, author, or similar rich metadata.

IBM DB2 for i (formerly known as DB2/400 and DB2 for i5/OS) is a database file system as part of the object based IBM i operating system (formerly known as OS/400 and i5/OS), incorporating a single level store and running on IBM Power Systems (formerly known as AS/400 and iSeries), designed by Frank G. Soltis IBM's former chief scientist for IBM i. Around 1978 to 1988 Frank G. Soltis and his team at IBM Rochester have successfully designed and applied technologies like the database file system where others like Microsoft later failed to accomplish. These technologies are informally known as 'Fortress Rochester' and were in few basic aspects extended from early Mainframe technologies but in many ways more advanced from a technological perspective.

Some other projects that aren't "pure" database file systems but that use some aspects of a database file system:

- Many Web content management systems use a relational DBMS to store and retrieve files. For example, XHTML files are stored as XML or text fields, while image files are stored as blob fields; SQL SELECT (with optional XPath) statements retrieve the files, and allow the use of a sophisticated logic and more rich information associations than "usual file systems." Many CMSs also have the option of storing only metadata within the database, with the standard filesystem used to store the content of files.

- Very large file systems, embodied by applications like Apache Hadoop and Google File System, use some database file system concepts.

Transactional file systems

Some programs need to either make multiple file system changes, or, if one or more of the changes fail for any reason, make none of the changes. For example, a program which is installing or updating software may write executables, libraries, and/or configuration files. If some of the writing fails and the software is left partially installed or updated, the software may be broken or unusable. An incomplete update of a key system utility, such as the command shell, may leave the entire system in an unusable state.

Transaction processing introduces the atomicity guarantee, ensuring that operations inside of a transaction are either all committed or the transaction can be aborted and the system discards all of its partial results. This means that if there is a crash or power failure, after recovery, the stored state will be consistent. Either the software will be completely installed or the failed installation will be completely rolled back, but an unusable partial install will not be left on the system. Transactions also provide the isolation guarantee, meaning that operations within a transaction are hidden from other threads on the system until the transaction commits, and that interfering operations on the system will be properly serialized with the transaction.

Windows, beginning with Vista, added transaction support to NTFS, in a feature called Transactional NTFS, but its use is now discouraged. There are a number of research prototypes of transactional file systems for UNIX systems, including the Valor file system, Amino, LFS, and a transactional ext3 file system on the TxOS kernel, as well as transactional file systems targeting embedded systems, such as TFFS.

Ensuring consistency across multiple file system operations is difficult, if not impossible, without file system transactions. File locking can be used as a concurrency control mechanism for individual files, but it typically does not protect the directory structure or file metadata. For instance, file locking cannot prevent TOCTTOU race conditions on symbolic links. File locking also cannot automatically roll back a failed operation, such as a software upgrade; this requires atomicity.

Journaling file systems is one technique used to introduce transaction-level consistency to file system structures. Journal transactions are not exposed to programs as part of the OS API; they are only used internally to ensure consistency at the granularity of a single system call.

Data backup systems typically do not provide support for direct backup of data stored in a transactional manner, which makes the recovery of reliable and consistent data sets difficult. Most backup software simply notes what files have changed since a certain time, regardless of the transactional state shared across multiple files in the overall dataset. As a workaround, some database systems simply produce an archived state file containing all data up to that point, and the backup software only backs that up and does not interact directly with the active transactional databases at all. Recovery requires separate recreation of the database from the state file after the file has been restored by the backup software.

Network file systems

A network file system is a file system that acts as a client for a remote file access protocol, providing access to files on a server. Programs using local interfaces can transparently create, manage and access hierarchical directories and files in remote network-connected computers. Examples of network file systems include clients for the NFS, AFS, SMB protocols, and file-system-like clients for FTP and WebDAV.

A shared disk file system is one in which a number of machines (usually servers) all have access to the same external disk subsystem (usually a storage area network). The file system arbitrates access to that subsystem, preventing write collisions. Examples include GFS2 from Red Hat, GPFS, now known as Spectrum Scale, from IBM, SFS from DataPlow, CXFS from SGI, StorNext from Quantum Corporation and ScoutFS from Versity.

Special file systems

A special file system presents non-file elements of an operating system as files so they can be acted on using file system APIs. This is most commonly done in Unix-like operating systems, but devices are given file names in some non-Unix-like operating systems as well.

Device file systems

A device file system represents I/O devices and pseudo-devices as files, called device files. Examples in Unix-like systems include devfs and, in Linux 2.6 systems, udev. In non-Unix-like systems, such as TOPS-10 and other operating systems influenced by it, where the full filename or pathname of a file can include a device prefix, devices other than those containing file systems are referred to by a device prefix specifying the device, without anything following it.

Other special file systems

- In the Linux kernel, configfs and sysfs provide files that can be used to query the kernel for information and configure entities in the kernel.

- procfs maps processes and, on Linux, other operating system structures into a filespace.

Minimal file system / audio-cassette storage

In the 1970s disk and digital tape devices were too expensive for some early microcomputer users. An inexpensive basic data storage system was devised that used common audio cassette tape.

When the system needed to write data, the user was notified to press "RECORD" on the cassette recorder, then press "RETURN" on the keyboard to notify the system that the cassette recorder was recording. The system wrote a sound to provide time synchronization, then modulated sounds that encoded a prefix, the data, a checksum and a suffix. When the system needed to read data, the user was instructed to press "PLAY" on the cassette recorder. The system would listen to the sounds on the tape waiting until a burst of sound could be recognized as the synchronization. The system would then interpret subsequent sounds as data. When the data read was complete, the system would notify the user to press "STOP" on the cassette recorder. It was primitive, but it (mostly) worked. Data was stored sequentially, usually in an unnamed format, although some systems (such as the Commodore PET series of computers) did allow the files to be named. Multiple sets of data could be written and located by fast-forwarding the tape and observing at the tape counter to find the approximate start of the next data region on the tape. The user might have to listen to the sounds to find the right spot to begin playing the next data region. Some implementations even included audible sounds interspersed with the data.

Flat file systems

In a flat file system, there are no subdirectories; directory entries for all files are stored in a single directory.

When floppy disk media was first available this type of file system was adequate due to the relatively small amount of data space available. CP/M machines featured a flat file system, where files could be assigned to one of 16 user areas and generic file operations narrowed to work on one instead of defaulting to work on all of them. These user areas were no more than special attributes associated with the files; that is, it was not necessary to define specific quota for each of these areas and files could be added to groups for as long as there was still free storage space on the disk. The early Apple Macintosh also featured a flat file system, the Macintosh File System. It was unusual in that the file management program (Macintosh Finder) created the illusion of a partially hierarchical filing system on top of EMFS. This structure required every file to have a unique name, even if it appeared to be in a separate folder. IBM DOS/360 and OS/360 store entries for all files on a disk pack (volume) in a directory on the pack called a Volume Table of Contents (VTOC).

While simple, flat file systems become awkward as the number of files grows and makes it difficult to organize data into related groups of files.

A recent addition to the flat file system family is Amazon's S3, a remote storage service, which is intentionally simplistic to allow users the ability to customize how their data is stored. The only constructs are buckets (imagine a disk drive of unlimited size) and objects (similar, but not identical to the standard concept of a file). Advanced file management is allowed by being able to use nearly any character (including '/') in the object's name, and the ability to select subsets of the bucket's content based on identical prefixes.

File systems and operating systems

Many operating systems include support for more than one file system. Sometimes the OS and the file system are so tightly interwoven that it is difficult to separate out file system functions.

There needs to be an interface provided by the operating system software between the user and the file system. This interface can be textual (such as provided by a command line interface, such as the Unix shell, or OpenVMS DCL) or graphical (such as provided by a graphical user interface, such as file browsers). If graphical, the metaphor of the folder, containing documents, other files, and nested folders is often used (see also: directory and folder).

Unix and Unix-like operating systems

Unix-like operating systems create a virtual file system, which makes all the files on all the devices appear to exist in a single hierarchy. This means, in those systems, there is one root directory, and every file existing on the system is located under it somewhere. Unix-like systems can use a RAM disk or network shared resource as its root directory.

Unix-like systems assign a device name to each device, but this is not how the files on that device are accessed. Instead, to gain access to files on another device, the operating system must first be informed where in the directory tree those files should appear. This process is called mounting a file system. For example, to access the files on a CD-ROM, one must tell the operating system "Take the file system from this CD-ROM and make it appear under such-and-such directory." The directory given to the operating system is called the mount point – it might, for example, be /media. The /media directory exists on many Unix systems (as specified in the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard) and is intended specifically for use as a mount point for removable media such as CDs, DVDs, USB drives or floppy disks. It may be empty, or it may contain subdirectories for mounting individual devices. Generally, only the administrator (i.e. root user) may authorize the mounting of file systems.

Unix-like operating systems often include software and tools that assist in the mounting process and provide it new functionality. Some of these strategies have been coined "auto-mounting" as a reflection of their purpose.

- In many situations, file systems other than the root need to be available as soon as the operating system has booted. All Unix-like systems therefore provide a facility for mounting file systems at boot time. System administrators define these file systems in the configuration file fstab (vfstab in Solaris), which also indicates options and mount points.

- In some situations, there is no need to mount certain file systems at boot time, although their use may be desired thereafter. There are some utilities for Unix-like systems that allow the mounting of predefined file systems upon demand.

- Removable media allow programs and data to be transferred between machines without a physical connection. Common examples include USB flash drives, CD-ROMs, and DVDs. Utilities have therefore been developed to detect the presence and availability of a medium and then mount that medium without any user intervention.

- Progressive Unix-like systems have also introduced a concept called supermounting; see, for example, the Linux supermount-ng project. For example, a floppy disk that has been supermounted can be physically removed from the system. Under normal circumstances, the disk should have been synchronized and then unmounted before its removal. Provided synchronization has occurred, a different disk can be inserted into the drive. The system automatically notices that the disk has changed and updates the mount point contents to reflect the new medium.

- An automounter will automatically mount a file system when a reference is made to the directory atop which it should be mounted. This is usually used for file systems on network servers, rather than relying on events such as the insertion of media, as would be appropriate for removable media.

Linux

Linux supports numerous file systems, but common choices for the system disk on a block device include the ext* family (ext2, ext3 and ext4), XFS, JFS, and btrfs. For raw flash without a flash translation layer (FTL) or Memory Technology Device (MTD), there are UBIFS, JFFS2 and YAFFS, among others. SquashFS is a common compressed read-only file system.

Solaris

Solaris in earlier releases defaulted to (non-journaled or non-logging) UFS for bootable and supplementary file systems. Solaris defaulted to, supported, and extended UFS.

Support for other file systems and significant enhancements were added over time, including Veritas Software Corp. (journaling) VxFS, Sun Microsystems (clustering) QFS, Sun Microsystems (journaling) UFS, and Sun Microsystems (open source, poolable, 128 bit compressible, and error-correcting) ZFS.

Kernel extensions were added to Solaris to allow for bootable Veritas VxFS operation. Logging or journaling was added to UFS in Sun's Solaris 7. Releases of Solaris 10, Solaris Express, OpenSolaris, and other open source variants of the Solaris operating system later supported bootable ZFS.

Logical Volume Management allows for spanning a file system across multiple devices for the purpose of adding redundancy, capacity, and/or throughput. Legacy environments in Solaris may use Solaris Volume Manager (formerly known as Solstice DiskSuite). Multiple operating systems (including Solaris) may use Veritas Volume Manager. Modern Solaris based operating systems eclipse the need for volume management through leveraging virtual storage pools in ZFS.

macOS

macOS (formerly Mac OS X) uses the Apple File System (APFS), which in 2017 replaced a file system inherited from classic Mac OS called HFS Plus (HFS+). Apple also uses the term "Mac OS Extended" for HFS+. HFS Plus is a metadata-rich and case-preserving but (usually) case-insensitive file system. Due to the Unix roots of macOS, Unix permissions were added to HFS Plus. Later versions of HFS Plus added journaling to prevent corruption of the file system structure and introduced a number of optimizations to the allocation algorithms in an attempt to defragment files automatically without requiring an external defragmenter.

Filenames can be up to 255 characters. HFS Plus uses Unicode to store filenames. On macOS, the filetype can come from the type code, stored in file's metadata, or the filename extension.

HFS Plus has three kinds of links: Unix-style hard links, Unix-style symbolic links, and aliases. Aliases are designed to maintain a link to their original file even if they are moved or renamed; they are not interpreted by the file system itself, but by the File Manager code in userland.

macOS 10.13 High Sierra, which was announced on June 5, 2017 at Apple's WWDC event, uses the Apple File System on solid-state drives.

macOS also supported the UFS file system, derived from the BSD Unix Fast File System via NeXTSTEP. However, as of Mac OS X Leopard, macOS could no longer be installed on a UFS volume, nor can a pre-Leopard system installed on a UFS volume be upgraded to Leopard. As of Mac OS X Lion UFS support was completely dropped.

Newer versions of macOS are capable of reading and writing to the legacy FAT file systems (16 and 32) common on Windows. They are also capable of reading the newer NTFS file systems for Windows. In order to write to NTFS file systems on macOS versions prior to Mac OS X Snow Leopard third party software is necessary. Mac OS X 10.6 (Snow Leopard) and later allow writing to NTFS file systems, but only after a non-trivial system setting change (third party software exists that automates this).

Finally, macOS supports reading and writing of the exFAT file system since Mac OS X Snow Leopard, starting from version 10.6.5.

OS/2

OS/2 1.2 introduced the High Performance File System (HPFS). HPFS supports mixed case file names in different code pages, long file names (255 characters), more efficient use of disk space, an architecture that keeps related items close to each other on the disk volume, less fragmentation of data, extent-based space allocation, a B+ tree structure for directories, and the root directory located at the midpoint of the disk, for faster average access. A journaled filesystem (JFS) was shipped in 1999.

PC-BSD

PC-BSD is a desktop version of FreeBSD, which inherits FreeBSD's ZFS support, similarly to FreeNAS. The new graphical installer of PC-BSD can handle / (root) on ZFS and RAID-Z pool installs and disk encryption using Geli right from the start in an easy convenient (GUI) way. The current PC-BSD 9.0+ 'Isotope Edition' has ZFS filesystem version 5 and ZFS storage pool version 28.

Plan 9

Plan 9 from Bell Labs treats everything as a file and accesses all objects as a file would be accessed (i.e., there is no ioctl or mmap): networking, graphics, debugging, authentication, capabilities, encryption, and other services are accessed via I/O operations on file descriptors. The 9P protocol removes the difference between local and remote files. File systems in Plan 9 are organized with the help of private, per-process namespaces, allowing each process to have a different view of the many file systems that provide resources in a distributed system.

The Inferno operating system shares these concepts with Plan 9.

Microsoft Windows

Windows makes use of the FAT, NTFS, exFAT, Live File System and ReFS file systems (the last of these is only supported and usable in Windows Server 2012, Windows Server 2016, Windows 8, Windows 8.1, and Windows 10; Windows cannot boot from it).

Windows uses a drive letter abstraction at the user level to distinguish one disk or partition from another. For example, the path C:\WINDOWS represents a directory WINDOWS on the partition represented by the letter C. Drive C: is most commonly used for the primary hard disk drive partition, on which Windows is usually installed and from which it boots. This "tradition" has become so firmly ingrained that bugs exist in many applications which make assumptions that the drive that the operating system is installed on is C. The use of drive letters, and the tradition of using "C" as the drive letter for the primary hard disk drive partition, can be traced to MS-DOS, where the letters A and B were reserved for up to two floppy disk drives. This in turn derived from CP/M in the 1970s, and ultimately from IBM's CP/CMS of 1967.

FAT

The family of FAT file systems is supported by almost all operating systems for personal computers, including all versions of Windows and MS-DOS/PC DOS, OS/2, and DR-DOS. (PC DOS is an OEM version of MS-DOS, MS-DOS was originally based on SCP's 86-DOS. DR-DOS was based on Digital Research's Concurrent DOS, a successor of CP/M-86.) The FAT file systems are therefore well-suited as a universal exchange format between computers and devices of most any type and age.

The FAT file system traces its roots back to an (incompatible) 8-bit FAT precursor in Standalone Disk BASIC and the short-lived MDOS/MIDAS project.

Over the years, the file system has been expanded from FAT12 to FAT16 and FAT32. Various features have been added to the file system including subdirectories, codepage support, extended attributes, and long filenames. Third parties such as Digital Research have incorporated optional support for deletion tracking, and volume/directory/file-based multi-user security schemes to support file and directory passwords and permissions such as read/write/execute/delete access rights. Most of these extensions are not supported by Windows.

The FAT12 and FAT16 file systems had a limit on the number of entries in the root directory of the file system and had restrictions on the maximum size of FAT-formatted disks or partitions.

FAT32 addresses the limitations in FAT12 and FAT16, except for the file size limit of close to 4 GB, but it remains limited compared to NTFS.

FAT12, FAT16 and FAT32 also have a limit of eight characters for the file name, and three characters for the extension (such as .exe). This is commonly referred to as the 8.3 filename limit. VFAT, an optional extension to FAT12, FAT16 and FAT32, introduced in Windows 95 and Windows NT 3.5, allowed long file names (LFN) to be stored in the FAT file system in a backwards compatible fashion.

NTFS

NTFS, introduced with the Windows NT operating system in 1993, allowed ACL-based permission control. Other features also supported by NTFS include hard links, multiple file streams, attribute indexing, quota tracking, sparse files, encryption, compression, and reparse points (directories working as mount-points for other file systems, symlinks, junctions, remote storage links).

exFAT

exFAT has certain advantages over NTFS with regard to file system overhead.

exFAT is not backward compatible with FAT file systems such as FAT12, FAT16 or FAT32. The file system is supported with newer Windows systems, such as Windows XP, Windows Server 2003, Windows Vista, Windows 2008, Windows 7, Windows 8, Windows 8.1, Windows 10 and Windows 11.

exFAT is supported in macOS starting with version 10.6.5 (Snow Leopard). Support in other operating systems is sparse since implementing support for exFAT requires a license. exFAT is the only file system that is fully supported on both macOS and Windows that can hold files larger than 4 GB.

OpenVMS

MVS

Prior to the introduction of VSAM, OS/360 systems implemented a hybrid file system. The system was designed to easily support removable disk packs, so the information relating to all files on one disk (volume in IBM terminology) is stored on that disk in a flat system file called the Volume Table of Contents (VTOC). The VTOC stores all metadata for the file. Later a hierarchical directory structure was imposed with the introduction of the System Catalog, which can optionally catalog files (datasets) on resident and removable volumes. The catalog only contains information to relate a dataset to a specific volume. If the user requests access to a dataset on an offline volume, and they have suitable privileges, the system will attempt to mount the required volume. Cataloged and non-cataloged datasets can still be accessed using information in the VTOC, bypassing the catalog, if the required volume id is provided to the OPEN request. Still later the VTOC was indexed to speed up access.

Conversational Monitor System

The IBM Conversational Monitor System (CMS) component of VM/370 uses a separate flat file system for each virtual disk (minidisk). File data and control information are scattered and intermixed. The anchor is a record called the Master File Directory (MFD), always located in the fourth block on the disk. Originally CMS used fixed-length 800-byte blocks, but later versions used larger size blocks up to 4K. Access to a data record requires two levels of indirection, where the file's directory entry (called a File Status Table (FST) entry) points to blocks containing a list of addresses of the individual records.

AS/400 file system

Data on the AS/400 and its successors consists of system objects mapped into the system virtual address space in a single-level store. Many types of objects are defined including the directories and files found in other file systems. File objects, along with other types of objects, form the basis of the AS/400's support for an integrated relational database.

Other file systems

- The Prospero File System is a file system based on the Virtual System Model. The system was created by Dr. B. Clifford Neuman of the Information Sciences Institute at the University of Southern California.

- RSRE FLEX file system - written in ALGOL 68

- The file system of the Michigan Terminal System (MTS) is interesting because: (i) it provides "line files" where record lengths and line numbers are associated as metadata with each record in the file, lines can be added, replaced, updated with the same or different length records, and deleted anywhere in the file without the need to read and rewrite the entire file; (ii) using program keys files may be shared or permitted to commands and programs in addition to users and groups; and (iii) there is a comprehensive file locking mechanism that protects both the file's data and its metadata.

Limitations

Converting the type of a file system

It may be advantageous or necessary to have files in a different file system than they currently exist. Reasons include the need for an increase in the space requirements beyond the limits of the current file system. The depth of path may need to be increased beyond the restrictions of the file system. There may be performance or reliability considerations. Providing access to another operating system which does not support the existing file system is another reason.

In-place conversion

In some cases conversion can be done in-place, although migrating the file system is more conservative, as it involves a creating a copy of the data and is recommended. On Windows, FAT and FAT32 file systems can be converted to NTFS via the convert.exe utility, but not the reverse. On Linux, ext2 can be converted to ext3 (and converted back), and ext3 can be converted to ext4 (but not back), and both ext3 and ext4 can be converted to btrfs, and converted back until the undo information is deleted. These conversions are possible due to using the same format for the file data itself, and relocating the metadata into empty space, in some cases using sparse file support.

Migrating to a different file system

Migration has the disadvantage of requiring additional space although it may be faster. The best case is if there is unused space on media which will contain the final file system.

For example, to migrate a FAT32 file system to an ext2 file system, a new ext2 file system is created. Then the data from the FAT32 file system is copied to the ext2 one, and the old file system is deleted.

An alternative, when there is not sufficient space to retain the original file system until the new one is created, is to use a work area (such as a removable media). This takes longer but has the benefit of producing a backup.

Long file paths and long file names

In hierarchical file systems, files are accessed by means of a path that is a branching list of directories containing the file. Different file systems have different limits on the depth of the path. File systems also have a limit on the length of an individual filename.

Copying files with long names or located in paths of significant depth from one file system to another may cause undesirable results. This depends on how the utility doing the copying handles the discrepancy.