The Peaceful Revolution (German: Friedliche Revolution), as a part of the Revolutions of 1989, was the process of sociopolitical change that led to the opening of East Germany's borders with the West, the end of the ruling of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) in the German Democratic Republic (GDR or "East Germany") in 1989 and the transition to a parliamentary democracy, which later enabled the reunification of Germany in October 1990. This happened through non-violent initiatives and demonstrations. This period of change is referred to in German as Die Wende (German pronunciation: [diː ˈvɛndə], "the turning point").

These events were closely linked to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's decision to abandon Soviet hegemony in Eastern Europe as well as the reformist movements that spread through Eastern Bloc countries. In addition to the Soviet Union's shift in foreign policy, the GDR's lack of competitiveness in the global market, as well as its sharply rising national debt, hastened the destabilization of the SED's one-party state.

Those driving the reform process within the GDR included intellectuals and church figures who had been in underground opposition for several years, people attempting to flee the country, and peaceful demonstrators who were no longer willing to yield to the threat of violence and repression.

Because of its hostile response to the reforms implemented within its "socialist brother lands", the SED leadership was already increasingly isolated within the Eastern Bloc when it permitted the opening of the border at the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989. Through a change in leadership and a willingness to negotiate, the SED attempted to win back the political initiative, but control of the situation increasingly lay with the West German government under Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

From December 1989, the GDR government of Prime Minister Hans Modrow was influenced by the Central Round Table, which put into action the dissolution of the Stasi and prepared free elections. After an election win for a coalition of parties that supported German reunification, the political path within the GDR was clear.

Timeline

Significant events:

- Late 1980s – The period of Soviet bloc liberalisation (Glasnost) and reform (Perestroika).

- 27 June 1989 – The opening of Hungary's border fence with Austria.

- 19 August 1989 – The Pan-European Picnic at the Hungarian-Austrian border, when hundreds of East Germans, who were allowed to travel to Hungary but not to the west, escaped to West Germany via Austria.

- From 4 September 1989 – Monday demonstrations in East Germany calling for the opening of the border with West Germany and greater human rights protections.

- 18 October 1989 – Erich Honecker removed as General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany.

- 9 November 1989 – The fall of the Berlin Wall, enabling East Germans to travel freely to the west.

- 3 December 1989 – The Socialist Unity Party's stepping down.

- 4 December 1989 – Citizens' occupations of Stasi buildings across the country, starting in Erfurt. The Stasi headquarters in Berlin were occupied on 15 January 1990.

- 13 January 1990 – The dissolution of the Stasi.

- 18 March 1990 - The 1990 East German general election, which was also a quasi-referendum on reunification, in which the Alliance for Germany, which supported reunification, got the highest proportion of votes.

- 1 July 1990 – The Währungs-, Wirtschafts- und Sozialunion (Monetary, Economy and Social Union) accord between East and West Germany, came into effect. East Germany adopted the West German currency on this day.

- 31 August 1990 – The signing of the Einigungsvertrag (Treaty of Unification) between the GDR and the Federal Republic of Germany on 31 August 1990 and the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany on 12 September 1990.

- 3 October 1990 – German reunification achieved with the five re-established East German states integrated into the Federal Republic of Germany.

Soviet policy toward the Eastern Bloc

A fundamental shift in Soviet policy toward the Eastern Bloc nations under Mikhail Gorbachev in the late 1980s was the prelude to widespread demonstrations against the Socialist Unity Party, which had ruled East Germany since the country was founded on 7 October 1949. Previous uprisings – East Germany (1953), Czechoslovakia (1953), Poland (1956), Hungary (1956) and the Prague Spring (1968) – were harshly put down by Soviet troops. The Soviet reaction to the Polish crisis of 1980–1981 was already one of non-intervention.

Having initiated a policy of glasnost (openness) and emphasized the need for perestroika (economic restructuring), in July 1989, Gorbachev permitted the Warsaw Pact nations to initiate their own political and economic reforms within the terms of the treaty.

The policy of non-interference in Soviet Bloc countries' internal affairs was made official with Gorbachev's statement on 26 October 1989 that the "Soviet Union has no moral or political right to interfere in the affairs of its East European neighbors". This was dubbed the Sinatra Doctrine, by Gorbachev's spokesman Gennadi Gerasimov who joked "You know the Frank Sinatra song, 'I Did It My Way'? Hungary and Poland are doing it their way."

East German reaction to Soviet reforms

Following the reforms, by 1988 relations had soured between Gorbachev and Honecker, although the relationship of KGB and the Stasi was still close.

In November 1988, the distribution of the Soviet monthly magazine Sputnik, was prohibited in East Germany because its new open political criticisms annoyed upper circles of the GDR leadership. This caused a lot of resentment and helped to activate the opposition movement. After a year, the sale of the magazine was reinstated, and censored editions of the issues from the preceding year were made available in a special edition for East Germans.

Catalysts for the crisis of 1989

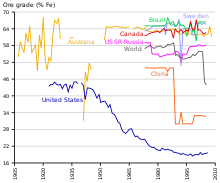

Economic situation

East Germany's economy was stronger than other Eastern Bloc countries and it was the most successful of the CMEA countries. It was the Soviet Union's most important trading partner, although it was very much subordinate. It was a net exporter of technology. Its shared language, cultural and personal connections with West Germany helped to boost its economy. Its trade with West Germany was 50 to 60 percent of its total trade with Western nations.

Although it was hailed as a communist success story, by the late 1980s its economic growth had slowed to less than 1% per annum and the government's economic goals were not reached. It had to deal with increasing global competition with run-down industrial infrastructure, and shortages of labour and raw materials. From 1986, its products were often seen as inferior and orders delivered to the Soviet Union were increasingly rejected due to poor quality control standards. Other communist countries were pursuing market-led reforms, but the government of Erich Honecker rejected such changes, claiming they contradicted Marxist ideology. More than one-fifth of the government's income was spent on subsidising the costs of housing, food and basic goods.

Poor sewerage and industrial infrastructure led to major environmental problems. Half the country's domestic sewage was untreated, as was most industrial waste. Over a third of all East Germany's rivers, and almost a third of its reservoirs and half of its lakes were severely polluted. Its forests were damaged by sulphur dioxide and air pollution in cities was a problem. Protests about these environmental problems played a large part in the Peaceful Revolution.

Workers in East Germany earned more than those in other communist countries and they had better housing than most of them. But East German workers compared themselves with West Germans, who were much better off, which was another cause of dissatisfaction.

Electoral fraud

In practice, there was no real choice in GDR elections, which consisted of citizens voting to approve a pre-selected list of National Front candidates. The National Front was, in theory, an alliance of political parties, but they were all controlled by the SED party, which controlled the Volkskammer, the East German parliament. The results of elections were generally about 99% "Yes" in favour of the list. However, before the 7 May 1989 election there were open signs of citizens' dissatisfaction with the government and the SED was concerned that there could be a significant number of "No" votes. The number of applications for an Ausreiseantrag (permission to leave the country) had increased and there was discontent about housing conditions and shortages of basic products.

In the weeks before the election, opposition activists called for it to be boycotted, and distributed a leaflet criticising Erich Honecker's regime. Nevertheless, the result of the election was proclaimed as 98.5% "Yes". Clear evidence of electoral fraud was smuggled to the West German media. When this information was broadcast, it was picked up in East Germany, instigating protests.

Citizens demanded their legal right to observe the vote count. Election monitors from churches and other groups showed the figures had been falsified. About 10% of voters had put a line through every name on the list, indicating a "No" vote, and about 10% of the electorate had not voted at all. After the initial protests on 7 May, there were demonstrations on the seventh of every month in Alexanderplatz in Berlin.

Gaps in the Iron Curtain

Background

The Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc states had strongly isolationist policies and they developed complex systems and infrastructure to restrict their citizens travel beyond the Iron Curtain. About 3.5 million people left the GDR for West Germany before the building of the Berlin Wall and the Inner German border in August 1961. After that it was still possible to leave legally, by applying for and receiving an Ausreiseantrag (permission to leave). Between 1961 and 1988 about 383,000 people left this way.

The government also forcibly exiled people, and political prisoners and their families could be ransomed to the West German government, although those involved had no choice in the matter. Between 1964 and 1989 a recorded 33,755 political prisoners and about 250,000 of their relatives and others were "sold" to West Germany.

Most of those who tried to escape illegally after 1961 travelled to other Eastern Bloc countries, as they believed their western borders were easier to breach than East Germany's. Around 7,000–8,000 East Germans escaped through Bulgaria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia between 1961 and 1988. However, the majority of attempts were thwarted and those caught were arrested and sent back to face the East German legal system. Some were also shot and killed by border guards.

Opening of the Hungarian and Czechoslovak borders

The Hungarian leader, János Kádár, retired on 22 May 1988 and other political parties were formed which challenged the old socialist order in Hungary, leading to a period of liberalisation. Almost a year later, on 2 May 1989, the Hungarian government began dismantling its border fence with Austria. This encouraged East German citizens to start travelling to Hungary in the hope of being able to get to the west more easily, not only over the border, but also by going to the West German embassy in Budapest and seeking asylum. On 27 June 1989 the Hungarian foreign minister Gyula Horn and his Austrian counterpart Alois Mock symbolically cut the border fence just outside Sopron. After the demolition of the border facilities, the patrols of the heavily armed Hungarian border guards were tightened and there was still a shooting order.

On 10 August 1989, Hungary announced it would be further relaxing its handling of first-time East German border offenders, which had already become lenient. It stamped the passports of people caught trying to illegally cross the border, rather than arresting them or reporting them to the East German authorities; first-time offenders would just get a warning, and no stamp. It also announced a proposal to downgrade illegal border crossing from a crime to a misdemeanour.

The Pan-European Picnic at the Austro-Hungarian border followed on 19 August 1989. This was a celebration of more open relationships between east and west, near Sopron, but on the Austrian side of the border. The opening of the border gate then set in motion a peaceful chain reaction, at the end of which there was no longer a GDR or an Iron Curtain, and the Eastern Bloc had disintegrated. The idea of opening the border at a ceremony came from Otto von Habsburg and was brought up by him to Miklós Németh, the then Hungarian Prime Minister, who promoted the idea. The border was temporarily opened at 3 pm, and 700–900 East Germans, who had travelled there after being tipped off, rushed across, without intervention from Hungarian border guards. It was the largest escape movement from East Germany since the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. The local organization in Sopron took over the Hungarian Democratic Forum, the other contacts were made via Habsburg and the Hungarian Minister of State Imre Pozsgay. Extensive advertising for the planned picnic was made by posters and flyers among the GDR holidaymakers in Hungary. The Austrian branch of the Paneuropean Union, which was then headed by Karl von Habsburg, distributed thousands of brochures inviting them to a picnic near the border at Sopron. Habsburg and Imre Pozsgay saw the event also as an opportunity to test Mikhail Gorbachev’s reaction to an opening of the border on the Iron Curtain. In particular, it was examined whether Moscow would give the Soviet troops stationed in Hungary the command to intervene. The West German government was already prepared for the mass escape, and trains and coaches were ready to take the escapees from Vienna to Giessen, near Frankfurt, where a refugee reception centre was waiting for the new arrivals. After the Pan-European Picnic, Erich Honecker dictated to the Daily Mirror of August 19, 1989: “Habsburg distributed leaflets far into Poland, on which the East German holidaymakers were invited to a picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given gifts, food and Deutsche Mark, and then they were persuaded to come to the West.” But with the mass exodus at the Pan-European Picnic, the subsequent hesitant behavior of the Socialist Unity Party of East Germany and the non-intervention of the Soviet Union broke the dams.

About 100,000 East Germans then travelled to Hungary, hoping to also get across the border. Many people camped in the garden of the West German embassy in Budapest, in parks and around the border areas. Although the East German government asked for these people to be deported back to the GDR, Hungary, which had signed the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees on 14 March 1989, refused.

From 10 September 1989, the Hungarian government allowed all East Germans to cross the Austro-Hungarian border without hindrance. Tens of thousands left and many also travelled to Czechoslovakia, whose government also gave in to demands to open its western border.

The East German government gave in to pressure to allow special trains carrying East German refugees from Prague to West Germany, to travel via East Germany. Between the first and eighth of October 1989, 14 so-called "Freedom Trains" (German: Flüchtlingszüge aus Prag) carried a total of 12,000 people to Hof, in Bavaria. Large crowds gathered to cheer the trains as they passed.

Newly formed opposition

As a result of new hopes inspired by the mass exodus of East Germans via Hungary, several opposition groups formed in Autumn 1989, with the aim of bringing about the same sorts of reforms in the GDR that had been instituted in Poland and Hungary.

The largest of these was the New Forum (German:Neues Forum). It was founded by the artist Bärbel Bohley along with Jens Reich and Jutta Seidel. It had over 200,000 members within a few weeks of being set up. On 20 September 1989 it applied to field candidates in the March 1990 general election. New Forum acted as an umbrella organisation for activist groups across the country. Other new political organisations including Democratic Awakening, United Left, and the Socialist Democratic Party formed. They all had similar aims, wanting greater democracy and environmental reforms.

Decisive events of 1989

Tiananmen Square protests

East Germans could see news about the Tiananmen Square democracy demonstration between April and June 1989 on West German television broadcasts. When the Chinese regime brutally crushed the demonstration on 3–4 June, several hundred and possibly several thousand protesters were killed. This caused concern for the nascent East German protest movement, that had demonstrated against electoral fraud in May. "We too feared the possibility of a 'Chinese solution,'" said Pastor Christian Fuehrer of the Nikolaikirche in Leipzig.

The Neues Deutschland, the official newspaper of the SED, supported the crackdown by the Chinese authorities. The German People's Congress proclaimed it was "a defeat for counter-revolutionary forces." Sixteen civil rights activists in East Berlin were arrested for protesting against the actions of the Chinese government.

However, growing political agitation in East Germany was part of wider liberalisation within the Soviet bloc resulting from Gorbachev's reforms – the country was not as isolated as China. Although Gorbachev visited Beijing in May 1989 to normalize Sino-Soviet relations, and the Chinese people were enthusiastic about his ideas, he had no influence with the Chinese government. Rather than stifle the East Germans' protests, the Tiananmen Square demonstration was further inspiration for their desire to instigate change.

40th anniversary of GDR

Celebrations for Republic Day on 7 October 1989, the 40th anniversary of the founding of the GDR, were marred by demonstrations. There had been protests in the preceding weeks, and Hungary and Czechoslovakia now allowed East Germans to travel freely across their borders to the west. From 1 to 8 October, 14 "Freedom Trains" took 12,000 East German refugees from Prague across GDR territory to West Germany, with cheers from East Germans as they passed. All were signs that the anniversary, which Mikhail Gorbachev attended, would not run smoothly.

Although there were almost 500,000 Soviet troops stationed in the GDR, they were not going to help suppress any demonstrations. It later emerged that Gorbachev had ordered that the troops were to stay in their barracks during the commemorations. As the reformist Gorbachev was paraded along Unter den Linden, cheering crowds lining the street called out "Gorbi, Gorbi," and "Gorbi, help us." However, there were still fears of a Tiananmen Square-style crackdown, as on 2 October, the SED party official Egon Krenz was in Beijing, at the anniversary of the founding of People's Republic of China. There, he said, "In the struggles of our time, the GDR and China stand side by side."

On 7 October, a candelight demonstration with 1,500 protesters around Gethsemane Church in Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin was crushed by security forces, who beat people up and made around 500 arrests. Other protests outside the Palace of the Republic were also brutally repressed.

There were protests throughout the country, the most organised being three consecutive demonstrations in Saxony on 7, 8 and 9 October in Plauen, Dresden and Leipzig respectively. In Leipzig, there was no violence, as the 70,000 participants were too many for the 8,000 armed security forces present to tackle. "The message from Leipzig soared over the entire country: The masses had the power to topple the regime peacefully".

When numerous East Germans were arrested for protesting the 40th-anniversary celebrations, many of them sang "The Internationale" in police custody to imply that they, rather than their captors, were the real revolutionaries.

On 18 October, only eleven days after these events, Honecker was removed as head of the party and the state and was replaced by Egon Krenz.

Weekly demonstrations

In addition to the GDR 40th anniversary demonstrations and the protests against electoral fraud, from September 1989 there were regular weekly pro-democracy demonstrations in towns and cities across the country. They are referred to as "Monday demonstrations" as that was the day they occurred in Leipzig, where they started, but they were staged on several days of the week. In Erfurt, for example, they happened on Thursdays. The first wave of these was from 4 September 1989 to March 1990. They continued sporadically until 1991.

The protesters called for an open border with West Germany, genuine democracy, and greater human rights and environmental protections. The most noted slogan protesters shouted was "Wir sind das Volk" ("We are the people"), meaning that in a real democracy, the people determine how the country is governed. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, in demonstrations calling for German reunification, this morphed into "Wir sind ein Volk" ("We are one people").

Churches were often pivotal in the demonstrations. The Leipzig "Monday demonstrations" stemmed from Monday prayer meetings at the Nikolaikirche (Church of St Nicholas). Prayers were said for people who had been mistreated by the state authorities, so the meetings took on a political character. The numbers attending grew and on 4 September 1989, it became a demonstration of over 1000 people in front of the church. The Stasi arrived to break it up, taking some demonstrators away in trucks.

The demonstrations became a regular weekly event in Leipzig and around the country, with tens of thousands joining in. There were mass arrests and beatings at the Leipzig demonstrations on 11 September and going through until 2 October. After the demonstration on 9 October, in which the security forces were completely outnumbered by the 70,000 protesters and unable to hinder them, the demonstrations in Leipzig and elsewhere remained relatively peaceful. The largest gatherings were the Alexanderplatz demonstration in Berlin on 4 November 1989, and 11 November in Leipzig, each with an estimated 500,000 protesters, although there are claims that up to 750,000 were at the Berlin demonstration.

On the 28 October 1989, to try to calm the protests, an amnesty was issued for political prisoners being held for border crimes or for participation in the weekly demonstrations.

The first wave of demonstrations ended in March 1990 due to the forthcoming free parliamentary elections on 18 March.

Plan X

On 8 October 1989, Erich Mielke and Erich Honecker ordered the Stasi to implement "Plan X"—the SED's plan to arrest and indefinitely detain 85,939 East Germans during a state of emergency. According to John Koehler, Plan X had been in preparation since 1979 and was, "a carbon copy of how the Nazi concentration camps got their start after Hitler came to power in 1933."

By 1984, 23 sites had been selected for "isolation and internment camps." Those who were to be imprisoned in them ran into six categories; including anyone who had ever been under surveillance for anti-state activities, including all members of peace movements which were not under Stasi control.

According to Anna Funder:

The plans contained exact provisions for the use of all available prisons and camps, and when those were full for the conversion of other buildings: Nazi detention centers, schools, hospitals, and factory holiday hostels. Every detail was foreseen, from where the doorbell was located on the house of each person to be arrested to the adequate supply of barbed wire and the rules of dress and etiquette in the camps...

However, when Mielke sent the orders, codenamed "Shield" (German: Schild), to each local Stasi precinct to begin the planned arrests, he was ignored. Terrified of an East German version of the mass lynchings of Hungarian secret police agents during the 1956 Revolution, Stasi agents throughout the GDR fortified their office-buildings and barricaded themselves inside.

Ruling party starts to lose power

On 18 October 1989, the 77-year-old Erich Honecker was replaced as the General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party by Egon Krenz. After the vote to oust Honecker passed, Stasi chief Erich Mielke "got nasty," and accused Honecker of political corruption. Honecker responded that Mielke should not open his mouth so much. Mielke responded by putting the last nail in Honecker's coffin. He announced that the Stasi had a file on the now-ousted leader. It contained proof of Honecker's corrupt business practices, sexual activities, and how, as a member of the underground Communist Party of Germany during the Nazi years, he had been arrested by the Gestapo and had named names.

Officially Honecker resigned due to ill health, but he had been sharply criticized by the party. Although Krenz, 52, was the youngest member of the Politburo, he was a hardliner who had congratulated the Chinese regime on its brutal crushing of the Tiananmen Square demonstration. The New Forum were doubtful about his ability to bring about reform, saying that "he would have to undertake 'tremendous efforts' to dispel the mistrust of a great part of the population."

Günter Mittag, who was responsible for managing the economy, and Joachim Hermann, editor of the Neues Deutschland and head of propaganda, were also removed from office.

On 7 November 1989, the entire Cabinet of the East German government, the 44-member Council of Ministers, led by Prime Minister Willi Stoph, resigned as a consequence of the political upheaval caused by the mass exodus of citizens via the Hungarian and Czechoslovakian borders and the ongoing protests. The Politburo of the SED remained the real holders of political power. Over 200,000 members of the SED had left the party during the previous two months. Hans Modrow became the prime minister and 17 November he formed a 28-member Council of Minister which included 11 non-SED ministers.

Krenz, the last SED leader of the GDR, was only in office for 46 days, resigning on 3 December, along with the rest of the SED Politburo and the Central Committee of the party. The country was then in practice run by Prime Minister Modrow. Krenz was succeeded as head of state by Manfred Gerlach.

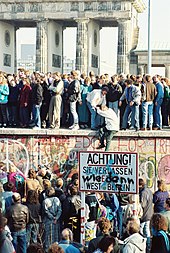

Fall of the Berlin Wall and border opening

After Hungary and Czechoslovakia allowed East Germans to cross to the west via their borders, there was nothing the GDR government could to do to prevent people leaving. Between 4–5 November, the weekend before the Berlin Wall was opened, over 50,000 people left. Party official Günter Schabowski announced at a press conference on the evening of Thursday 9 November 1989 that East Germans were free to travel through the checkpoints of the Berlin Wall and the inner German border.

After some initial confusion, with 20,000 people arriving at the Bornholmer Straße border crossing by 11.30 pm, chanting "Open the gate", Harald Jäger, a border official, allowed people to pass through into West Berlin. Over the next few days streams of cars queued at the checkpoints along the Berlin Wall and the inner German border to travel through to West Germany.

From 10 November, East Germans who had crossed the border queued outside West German banks to collect their Begrüßungsgeld ("Welcome Money"). This was a payment that the West German government had given to visiting East Germans since 1970. In 1989 the amount was 100 Deutsche Marks once per annum. Because East Germans' travel to the west had been very restricted, until the middle of the 1980s only about 60,000 visitors had received "Welcome Money". However, between 9 and 22 November alone, over 11 million East Germans had crossed into West Berlin or West Germany. In November and December about 4 billion DM was paid out, and the system was stopped on 29 December 1989.

Political situation during the transition

The fall of the Berlin Wall and opening of the inner German border set new challenges for both the government and the opposition in the GDR as well as those in power in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). General opinion was that the fate of the GDR rested with the attitude of the Soviet Union. In his memoirs, West German chancellor Helmut Kohl wrote that he had confronted Gorbachev in June 1989 with the view that German unity would arrive as surely as the Rhine would arrive at the sea; Gorbachev did not dispute this.

After 9 November there was not only a wave of demonstrations across the GDR but also a strong shift in the prevailing attitude to solutions. Instead of the chant "we are the people", the new refrain was "we are one people!" A problem for both the East and the West remained the continually high numbers moving from the GDR to the FRG, which created a destabilizing effect in the GDR while also placing a larger burden on the FRG to handle and integrate such large numbers.

Kohl's reunification plan

On the day the Berlin Wall fell, West German chancellor Kohl and his foreign minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher were on a state visit to Poland, which was cut short for the new situation. Only a day earlier, Kohl had set out new conditions for closer collaboration with the GDR leadership: the SED's abandonment of its monopoly on power, the allowing of independent parties, free elections, and the building up of a market economy. During a telephone conversation on 11 November 1989 with SED General Secretary Egon Krenz, who insisted that reunification was not on the agenda, Kohl conceded that the creation of "reasonable relations" was currently most pressing.

At first Kohl refrained from pushing for reunification to avoid raising annoyance abroad. His closest foreign adviser, Horst Teltschik, took heart though from opinion polls on 20 November 1989, which showed 70% of West Germans in favor of reunification and 48% considered it possible within ten years. More than 75% approved of financial aid for the GDR, though without tax increases. From Nikolai Portugalow, an emissary of Gorbachev's, Teilschik learned that Hans Modrow's suggestion of a treaty between the German states had prompted the Soviets to plan for "the unthinkable".

With Kohl's blessing, Teltschik developed a path for German unification. To his "Ten Point Program for Overcoming the Division of Germany and Europe", Kohl made some additions and read it aloud in parliament on 28 November 1989. Starting with immediate measures, the path included a contractual arrangement and the development of confederative structures to conclude with one federation.

The plan was broadly accepted in parliament with the exception of the Green Party, which endorsed the independence of the GDR in "a third way". The Social Democratic Party (SPD) was skeptical and divided. Former chancellor Willy Brandt coined the expression "Now grows together, what belongs together" on 10 November 1989. Oskar Lafontaine, soon to be the SPD's chancellor candidate, emphasised the incalculable financial risks and the curtailment of the number of those leaving.

International reactions to developments

The sudden announcement of Kohl's plan irritated European heads of states and Soviet chief Gorbachev. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher saw international stability becoming endangered and raised doubts about the peacefulness of a united and restrengthened Germany. French President François Mitterrand was concerned that the German government could give up its commitment to the European integration process and instead focus on its national interests and ambitions for power. In early December 1989, he and Gorbachev sought to ensure "that the whole European process develops faster than the German question and that it overtakes the German development. We must form pan-European structures." Gorbachev informed West German foreign minister Genscher that Kohl was behaving "like a bull in a china shop".

In light of these frosty reactions, the West German government viewed a meeting of the four Allied powers on 11 December 1989 as a demonstrative affront. Only the United States government, under George H. W. Bush, offered the West German chancellor support by setting out its own interests in any potential German reunification the day after Kohl's plan.

Kohl stressed that the driving factor behind the developments was the GDR populace and not the FRG government, which was itself surprised by the events and had to react. He aimed to preempt a state visit by Mitterrand on 20–22 December 1989 and planned talks with Minister President Modrow. In Dresden on 19 December, Kohl spoke before a crowd of 100,000, who broke out into cheers when he stated: "My goal remains—if the historical hour allows—the uniting of our nation".

When Mitterrand realized that controlling development from outside was not possible, he sought to commit the West German government to a foreseeable united Germany on two matters: on the recognition of Poland's western border and on hastened European integration through the establishment of a currency union. In January 1990, the Soviet Union sent understanding signals by appealing to West Germany for food deliveries. On 10 February 1990, Kohl and his advisers had positive talks with Gorbachev in Moscow.

Situation in the GDR

After his election as Minister President in the People's Chamber on 13 November 1989, Hans Modrow affirmed on 16 November that, from the GDR viewpoint, reunification was not on the agenda.

Since the end of October, opposition groups had called for the creation of a round table. They released a communal statement: "In light of the critical situation in our country, which can no longer be controlled by the previous power and responsibility structures, we demand that representatives of the GDR population come together to negotiate at a round table, to established conditions for constitutional reform and for free elections."

East German author Christa Wolf, who on the night before the opening of the border had called for people to remain in the GDR, read an appeal titled "For Our Country" on 28 November 1989; it was supported by GDR artists and civil liberties campaigners as well as critical SED members. During a press conference the same day, the author Stefan Heym also read the appeal, and within a few days it had received 1.17 million signatures. It called for "a separate identity for the GDR" to be established and warned against a "sell-out of our material and moral values" through reunification, stating there was still "the chance to develop a socialist alternative to the FRG as an equal partner amongst the states of Europe".

At the first meeting of the Central Round Table on 7 December 1989, the participants defined the new body as an advisory and decision-making institution. Unlike the Polish example, where the Solidarity delegates confronted the government, the Central Round Table was formed from representatives of numerous new opposition groups and delegates in equal number from the SED, bloc parties, and the SED-linked mass organizations. Church representatives acted as moderators.

The socialist reform program of Modrow's government lacked support both domestically and internationally. On a visit to Moscow in January 1990, Modrow admitted to Gorbachev: "The growing majority of the GDR population no longer supports the idea of the existence of two German states; it no longer seems possible to sustain this idea. … If we don't grasp the initiative now, then the process already set in motion will spontaneously and eruptively continue onward without us being able to have any influence upon it".

To expand the trust in his own government for the transitional phase until free elections, on 22 January 1990 Modrow offered the opposition groups the chance to participate in government. The majority of these groups agreed to a counteroffer of placing candidates from the Central Round Table in a non-party transitional government. Modrow considered this an attempt to dismantle his government and rejected it on 28 January. After lengthy negotiations and Modrow's threatening to resign, the opposition relented and accepted a place in the government as "ministers without portfolio". However, when Modrow committed to a one-nation Germany a few days later, the United Left withdrew its acceptance due to "a breach of trust" and rejected being involving in the government.

After the entry into the cabinet on 5 February 1990, all nine new "ministers" traveled with Modrow to Bonn for talks with the West German government on 13 February. As with Kohl's visit to Dresden two months earlier, Modrow was denied immediate financial support to avoid the threat of insolvency (although a prospective currency union had been on offer for several days). The talks were largely unproductive, with Kohl unwilling to make any decisive appointments with the pivotal election only weeks away.