Alternation of generations (also known as metagenesis or heterogenesis) is the predominant type of life cycle in plants and algae. In plants both phases are multicellular: the haploid sexual phase – the gametophyte – alternates with a diploid asexual phase – the sporophyte.

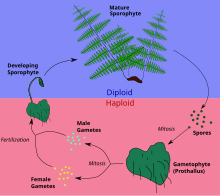

A mature sporophyte produces haploid spores by meiosis, a process which reduces the number of chromosomes to half, from two sets to one. The resulting haploid spores germinate and grow into multicellular haploid gametophytes. At maturity, a gametophyte produces gametes by mitosis, the normal process of cell division in eukaryotes, which maintains the original number of chromosomes. Two haploid gametes (originating from different organisms of the same species or from the same organism) fuse to produce a diploid zygote, which divides repeatedly by mitosis, developing into a multicellular diploid sporophyte. This cycle, from gametophyte to sporophyte (or equally from sporophyte to gametophyte), is the way in which all land plants and most algae undergo sexual reproduction.

The relationship between the sporophyte and gametophyte phases varies among different groups of plants. In the majority of algae, the sporophyte and gametophyte are separate independent organisms, which may or may not have a similar appearance. In liverworts, mosses and hornworts, the sporophyte is less well developed than the gametophyte and is largely dependent on it. Although moss and hornwort sporophytes can photosynthesise, they require additional photosynthate from the gametophyte to sustain growth and spore development and depend on it for supply of water, mineral nutrients and nitrogen. By contrast, in all modern vascular plants the gametophyte is less well developed than the sporophyte, although their Devonian ancestors had gametophytes and sporophytes of approximately equivalent complexity. In ferns the gametophyte is a small flattened autotrophic prothallus on which the young sporophyte is briefly dependent for its nutrition. In flowering plants, the reduction of the gametophyte is much more extreme; it consists of just a few cells which grow entirely inside the sporophyte.

Animals develop differently. They directly produce haploid gametes. No haploid spores capable of dividing are produced, so generally there is no multicellular haploid phase. Some insects have a sex-determining system whereby haploid males are produced from unfertilized eggs; however females produced from fertilized eggs are diploid.

Life cycles of plants and algae with alternating haploid and diploid multicellular stages are referred to as diplohaplontic. The equivalent terms haplodiplontic, diplobiontic and dibiontic are also in use, as is describing such an organism as having a diphasic ontogeny. Life cycles of animals, in which there is only a diploid multicellular stage, are referred to as diplontic. Life cycles in which there is only a haploid multicellular stage are referred to as haplontic.

Definition

Alternation of generations is defined as the alternation of multicellular diploid and haploid forms in the organism's life cycle, regardless of whether these forms are free-living. In some species, such as the alga Ulva lactuca, the diploid and haploid forms are indeed both free-living independent organisms, essentially identical in appearance and therefore said to be isomorphic. In many algae, the free-swimming, haploid gametes form a diploid zygote which germinates into a multicellular diploid sporophyte. The sporophyte produces free-swimming haploid spores by meiosis that germinate into haploid gametophytes.

However, in land plants, either the sporophyte or the gametophyte is very much reduced and is incapable of free living. For example, in all bryophytes the gametophyte generation is dominant and the sporophyte is dependent on it. By contrast, in all seed plants the gametophytes are strongly reduced, although the fossil evidence indicates that they were derived from isomorphic ancestors. In seed plants, the female gametophyte develops totally within the sporophyte, which protects and nurtures it and the embryonic sporophyte that it produces. The pollen grains, which are the male gametophytes, are reduced to only a few cells (just three cells in many cases). Here the notion of two generations is less obvious; as Bateman & Dimichele say "sporophyte and gametophyte effectively function as a single organism". The alternative term 'alternation of phases' may then be more appropriate.

History

Debates about alternation of generations in the early twentieth century can be confusing because various ways of classifying "generations" co-exist (sexual vs. asexual, gametophyte vs. sporophyte, haploid vs. diploid, etc.).

Initially, Chamisso and Steenstrup described the succession of differently organized generations (sexual and asexual) in animals as "alternation of generations", while studying the development of tunicates, cnidarians and trematode animals. This phenomenon is also known as heterogamy. Presently, the term "alternation of generations" is almost exclusively associated with the life cycles of plants, specifically with the alternation of haploid gametophytes and diploid sporophytes.

Wilhelm Hofmeister demonstrated the morphological alternation of generations in plants, between a spore-bearing generation (sporophyte) and a gamete-bearing generation (gametophyte). By that time, a debate emerged focusing on the origin of the asexual generation of land plants (i.e., the sporophyte) and is conventionally characterized as a conflict between theories of antithetic (Čelakovský, 1874) and homologous (Pringsheim, 1876) alternation of generations. Čelakovský coined the words sporophyte and gametophyte.

Eduard Strasburger (1874) discovered the alternation between diploid and haploid nuclear phases, also called cytological alternation of nuclear phases. Although most often coinciding, morphological alternation and nuclear phases alternation are sometimes independent of one another, e.g., in many red algae, the same nuclear phase may correspond to two diverse morphological generations. In some ferns which lost sexual reproduction, there is no change in nuclear phase, but the alternation of generations is maintained.

Alternation of generations in plants

Fundamental elements

The diagram above shows the fundamental elements of the alternation of generations in plants. There are many variations in different groups of plants. The processes involved are as follows:

- Two single-celled haploid gametes, each containing n unpaired chromosomes, fuse to form a single-celled diploid zygote, which now contains n pairs of chromosomes, i.e. 2n chromosomes in total.follows:

- The single-celled diploid zygote germinates, dividing by the normal process (mitosis), which maintains the number of chromosomes at 2n. The result is a multi-cellular diploid organism, called the sporophyte (because at maturity it produces spores).

- When it reaches maturity, the sporophyte produces one or more sporangia (singular: sporangium) which are the organs that produce diploid spore mother cells (sporocytes). These divide by a special process (meiosis) that reduces the number of chromosomes by a half. This initially results in four single-celled haploid spores, each containing n unpaired chromosomes.

- The single-celled haploid spore germinates, dividing by the normal process (mitosis), which maintains the number of chromosomes at n. The result is a multi-cellular haploid organism, called the gametophyte (because it produces gametes at maturity).

- When it reaches maturity, the gametophyte produces one or more gametangia (singular: gametangium) which are the organs that produce haploid gametes. At least one kind of gamete possesses some mechanism for reaching another gamete in order to fuse with it.

The 'alternation of generations' in the life cycle is thus between a diploid (2n) generation of multicellular sporophytes and a haploid (n) generation of multicellular gametophytes.

The situation is quite different from that in animals, where the fundamental process is that a multicellular diploid (2n) individual directly produces haploid (n) gametes by meiosis. In animals, spores (i.e. haploid cells which are able to undergo mitosis) are not produced, so there is no asexual multicellular generation. Some insects have haploid males that develop from unfertilized eggs, but the females are all diploid.

Variations

The diagram shown above is a good representation of the life cycle of some multi-cellular algae (e.g. the genus Cladophora) which have sporophytes and gametophytes of almost identical appearance and which do not have different kinds of spores or gametes.

However, there are many possible variations on the fundamental elements of a life cycle which has alternation of generations. Each variation may occur separately or in combination, resulting in a bewildering variety of life cycles. The terms used by botanists in describing these life cycles can be equally bewildering. As Bateman and Dimichele say "[...] the alternation of generations has become a terminological morass; often, one term represents several concepts or one concept is represented by several terms."

Possible variations are:

- Relative importance of the sporophyte and the gametophyte.

- Equal (homomorphy or isomorphy).

Filamentous algae of the genus Cladophora, which are predominantly found in fresh water, have diploid sporophytes and haploid gametophytes which are externally indistinguishable. No living land plant has equally dominant sporophytes and gametophytes, although some theories of the evolution of alternation of generations suggest that ancestral land plants did. - Unequal (heteromorphy or anisomorphy).

Gametophyte of Mnium hornum, a moss. - Dominant gametophyte (gametophytic).

In liverworts, mosses and hornworts, the dominant form is the haploid gametophyte. The diploid sporophyte is not capable of an independent existence, gaining most of its nutrition from the parent gametophyte, and having no chlorophyll when mature.

Sporophyte of Lomaria discolor, a fern. - Dominant sporophyte (sporophytic).

In ferns, both the sporophyte and the gametophyte are capable of living independently, but the dominant form is the diploid sporophyte. The haploid gametophyte is much smaller and simpler in structure. In seed plants, the gametophyte is even more reduced (at the minimum to only three cells), gaining all its nutrition from the sporophyte. The extreme reduction in the size of the gametophyte and its retention within the sporophyte means that when applied to seed plants the term 'alternation of generations' is somewhat misleading: "[s]porophyte and gametophyte effectively function as a single organism". Some authors have preferred the term 'alternation of phases'.

- Dominant gametophyte (gametophytic).

- Equal (homomorphy or isomorphy).

- Differentiation of the gametes.

- Both gametes the same (isogamy).

Like other species of Cladophora, C. callicoma has flagellated gametes which are identical in appearance and ability to move. - Gametes of two distinct sizes (anisogamy).

- Both of similar motility.

Species of Ulva, the sea lettuce, have gametes which all have two flagella and so are motile. However they are of two sizes: larger 'female' gametes and smaller 'male' gametes. - One large and sessile, one small and motile (oogamy). The larger sessile megagametes are eggs (ova), and smaller motile microgametes

are sperm (spermatozoa, spermatozoids). The degree of motility of the

sperm may be very limited (as in the case of flowering plants) but all

are able to move towards the sessile eggs. When (as is almost always the

case) the sperm and eggs are produced in different kinds of gametangia,

the sperm-producing ones are called antheridia (singular antheridium) and the egg-producing ones archegonia (singular archegonium).

Gametophyte of Pellia epiphylla with sporophytes growing from the remains of archegonia. - Antheridia and archegonia occur on the same gametophyte, which is then called monoicous.

(Many sources, including those concerned with bryophytes, use the term

'monoecious' for this situation and 'dioecious' for the opposite. Here 'monoecious' and 'dioecious' are used only for sporophytes.)

The liverwort Pellia epiphylla has the gametophyte as the dominant generation. It is monoicous: the small reddish sperm-producing antheridia are scattered along the midrib while the egg-producing archegonia grow nearer the tips of divisions of the plant. - Antheridia and archegonia occur on different gametophytes, which are then called dioicous.

The moss Mnium hornum has the gametophyte as the dominant generation. It is dioicous: male plants produce only antheridia in terminal rosettes, female plants produce only archegonia in the form of stalked capsules. Seed plant gametophytes are also dioicous. However, the parent sporophyte may be monoecious, producing both male and female gametophytes or dioecious, producing gametophytes of one gender only. Seed plant gametophytes are extremely reduced in size; the archegonium consists only of a small number of cells, and the entire male gametophyte may be represented by only two cells.

- Antheridia and archegonia occur on the same gametophyte, which is then called monoicous.

(Many sources, including those concerned with bryophytes, use the term

'monoecious' for this situation and 'dioecious' for the opposite. Here 'monoecious' and 'dioecious' are used only for sporophytes.)

- Both of similar motility.

- Both gametes the same (isogamy).

- Differentiation of the spores.

- All spores the same size (homospory or isospory).

Horsetails (species of Equisetum) have spores which are all of the same size. - Spores of two distinct sizes (heterospory or anisospory): larger megaspores and smaller microspores. When the two kinds of spore are produced in different kinds of sporangia, these are called megasporangia and microsporangia. A megaspore often (but not always) develops at the expense of the other three cells resulting from meiosis, which abort.

- Megasporangia and microsporangia occur on the same sporophyte, which is then called monoecious.

Most flowering plants fall into this category. Thus the flower of a lily contains six stamens (the microsporangia) which produce microspores which develop into pollen grains (the microgametophytes), and three fused carpels which produce integumented megasporangia (ovules) each of which produces a megaspore which develops inside the megasporangium to produce the megagametophyte. In other plants, such as hazel, some flowers have only stamens, others only carpels, but the same plant (i.e. sporophyte) has both kinds of flower and so is monoecious.

Flowers of European holly, a dioecious species: male above, female below (leaves cut to show flowers more clearly) - Megasporangia and microsporangia occur on different sporophytes, which are then called dioecious.

An individual tree of the European holly (Ilex aquifolium) produces either 'male' flowers which have only functional stamens (microsporangia) producing microspores which develop into pollen grains (microgametophytes) or 'female' flowers which have only functional carpels producing integumented megasporangia (ovules) that contain a megaspore that develops into a multicellular megagametophyte.

- Megasporangia and microsporangia occur on the same sporophyte, which is then called monoecious.

- All spores the same size (homospory or isospory).

There are some correlations between these variations, but they are just that, correlations, and not absolute. For example, in flowering plants, microspores ultimately produce microgametes (sperm) and megaspores ultimately produce megagametes (eggs). However, in ferns and their allies there are groups with undifferentiated spores but differentiated gametophytes. For example, the fern Ceratopteris thalictrioides has spores of only one kind, which vary continuously in size. Smaller spores tend to germinate into gametophytes which produce only sperm-producing antheridia.

A complex life cycle

Plant life cycles can be complex. Alternation of generations can take place in plants which are at once heteromorphic, sporophytic, oogametic, dioicous, heterosporic and dioecious, such as in a willow tree (as most species of the genus Salix are dioecious). The processes involved are:

- An immobile egg, contained in the archegonium, fuses with a

mobile sperm, released from an antheridium. The resulting zygote is

either 'male' or 'female'.

- A 'male' zygote develops by mitosis into a microsporophyte,

which at maturity produces one or more microsporangia. Microspores

develop within the microsporangium by meiosis.

In a willow (like all seed plants) the zygote first develops into an embryo microsporophyte within the ovule (a megasporangium enclosed in one or more protective layers of tissue known as integument). At maturity, these structures become the seed. Later the seed is shed, germinates and grows into a mature tree. A 'male' willow tree (a microsporophyte) produces flowers with only stamens, the anthers of which are the microsporangia. - Microspores germinate producing microgametophytes; at maturity one

or more antheridia are produced. Sperm develop within the antheridia.

In a willow, microspores are not liberated from the anther (the microsporangium), but develop into pollen grains (microgametophytes) within it. The whole pollen grain is moved (e.g. by an insect or by the wind) to an ovule (megagametophyte), where a sperm is produced which moves down a pollen tube to reach the egg. - A 'female' zygote develops by mitosis into a megasporophyte, which

at maturity produces one or more megasporangia. Megaspores develop

within the megasporangium; typically one of the four spores produced by

meiosis gains bulk at the expense of the remaining three, which

disappear.

'Female' willow trees (megasporophytes) produce flowers with only carpels (modified leaves that bear the megasporangia). - Megaspores germinate producing megagametophytes; at maturity one or

more archegonia are produced. Eggs develop within the archegonia.

The carpels of a willow produce ovules, megasporangia enclosed in integuments. Within each ovule, a megaspore develops by mitosis into a megagametophyte. An archegonium develops within the megagametophyte and produces an egg. The whole of the gametophytic 'generation' remains within the protection of the sporophyte except for pollen grains (which have been reduced to just three cells contained within the microspore wall).

- A 'male' zygote develops by mitosis into a microsporophyte,

which at maturity produces one or more microsporangia. Microspores

develop within the microsporangium by meiosis.

Life cycles of different plant groups

The term "plants" is taken here to mean the Archaeplastida, i.e. the glaucophytes, red and green algae and land plants.

Alternation of generations occurs in almost all multicellular red and green algae, both freshwater forms (such as Cladophora) and seaweeds (such as Ulva). In most, the generations are homomorphic (isomorphic) and free-living. Some species of red algae have a complex triphasic alternation of generations, in which there is a gametophyte phase and two distinct sporophyte phases. For further information, see Red algae: Reproduction.

Land plants all have heteromorphic (anisomorphic) alternation of generations, in which the sporophyte and gametophyte are distinctly different. All bryophytes, i.e. liverworts, mosses and hornworts, have the gametophyte generation as the most conspicuous. As an illustration, consider a monoicous moss. Antheridia and archegonia develop on the mature plant (the gametophyte). In the presence of water, the biflagellate sperm from the antheridia swim to the archegonia and fertilisation occurs, leading to the production of a diploid sporophyte. The sporophyte grows up from the archegonium. Its body comprises a long stalk topped by a capsule within which spore-producing cells undergo meiosis to form haploid spores. Most mosses rely on the wind to disperse these spores, although Splachnum sphaericum is entomophilous, recruiting insects to disperse its spores.

-

Alternation of generations in liverworts

-

Moss life cycle

-

Hornwort life cycle

The life cycle of ferns and their allies, including clubmosses and horsetails, the conspicuous plant observed in the field is the diploid sporophyte. The haploid spores develop in sori on the underside of the fronds and are dispersed by the wind (or in some cases, by floating on water). If conditions are right, a spore will germinate and grow into a rather inconspicuous plant body called a prothallus. The haploid prothallus does not resemble the sporophyte, and as such ferns and their allies have a heteromorphic alternation of generations. The prothallus is short-lived, but carries out sexual reproduction, producing the diploid zygote that then grows out of the prothallus as the sporophyte.

-

Alternation of generations in ferns

-

A gametophyte (prothallus) of Dicksonia

-

A sporophyte of Dicksonia antarctica

-

Dicksonia antarctica frond with spore-producing structures

In the spermatophytes, the seed plants, the sporophyte is the dominant multicellular phase; the gametophytes are strongly reduced in size and very different in morphology. The entire gametophyte generation, with the sole exception of pollen grains (microgametophytes), is contained within the sporophyte. The life cycle of a dioecious flowering plant (angiosperm), the willow, has been outlined in some detail in an earlier section (A complex life cycle). The life cycle of a gymnosperm is similar. However, flowering plants have in addition a phenomenon called 'double fertilization'. In the process of double fertilization, two sperm nuclei from a pollen grain (the microgametophyte), rather than a single sperm, enter the archegonium of the megagametophyte; one fuses with the egg nucleus to form the zygote, the other fuses with two other nuclei of the gametophyte to form 'endosperm', which nourishes the developing embryo.

Evolution of the dominant diploid phase

It has been proposed that the basis for the emergence of the diploid phase of the life cycle (sporophyte) as the dominant phase (e.g. as in vascular plants) is that diploidy allows masking of the expression of deleterious mutations through genetic complementation. Thus if one of the parental genomes in the diploid cells contained mutations leading to defects in one or more gene products, these deficiencies could be compensated for by the other parental genome (which nevertheless may have its own defects in other genes). As the diploid phase was becoming predominant, the masking effect likely allowed genome size, and hence information content, to increase without the constraint of having to improve accuracy of DNA replication. The opportunity to increase information content at low cost was advantageous because it permitted new adaptations to be encoded. This view has been challenged, with evidence showing that selection is no more effective in the haploid than in the diploid phases of the lifecycle of mosses and angiosperms.

-

Angiosperm life cycle

-

Tip of tulip stamen showing pollen (microgametophytes)

-

Plant ovules (megagametophytes): gymnosperm ovule on left, angiosperm ovule (inside ovary) on right

-

Double fertilization

Similar processes in other organisms

Rhizaria

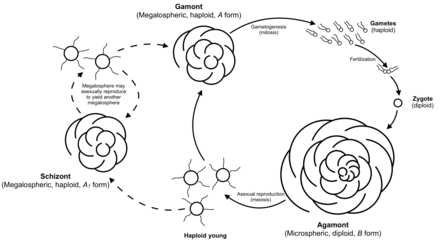

Some organisms currently classified in the clade Rhizaria and thus not plants in the sense used here, exhibit alternation of generations. Most Foraminifera undergo a heteromorphic alternation of generations between haploid gamont and diploid agamont forms. The diploid form is typically much larger than the haploid form; these forms are known as the microsphere and megalosphere, respectively.

Fungi

Fungal mycelia are typically haploid. When mycelia of different mating types meet, they produce two multinucleate ball-shaped cells, which join via a "mating bridge". Nuclei move from one mycelium into the other, forming a heterokaryon (meaning "different nuclei"). This process is called plasmogamy. Actual fusion to form diploid nuclei is called karyogamy, and may not occur until sporangia are formed. Karogamy produces a diploid zygote, which is a short-lived sporophyte that soon undergoes meiosis to form haploid spores. When the spores germinate, they develop into new mycelia.

Slime moulds

The life cycle of slime moulds is very similar to that of fungi. Haploid spores germinate to form swarm cells or myxamoebae. These fuse in a process referred to as plasmogamy and karyogamy to form a diploid zygote. The zygote develops into a plasmodium, and the mature plasmodium produces, depending on the species, one to many fruiting bodies containing haploid spores.