LGBT psychology is a field of psychology of surrounding the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals, in the particular the diverse range of psychological perspectives and experiences of these individuals. It covers different aspects such as identity development including the coming out process, parenting and family practices and support for LGBTQ+ individuals, as well as issues of prejudice and discrimination involving the LGBT community.

Definition

LGBTQ psychology stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer psychology. This list is not inclusive to all people within the community and the plus represents other identities not covered within the acronym. In the past this field was known as lesbian and gay psychology. Now it also includes bisexual and transgender identities and behaviors. In addition, the "Q" stands for queer which includes sexual identities and behaviors that go beyond traditional sex and gender labels, roles, and expectations.

The word "queer" was historically a slur used towards people within the community. Those who identify as queer today have reclaimed this label as self-identification. However, due to the traditional use of the word, many people in the LGBT community continue to reject this label. Some of the identities that fall under the term queer are aromantic, demi-sexual, asexual, non-binary, agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, pansexual, intersex, genderqueer, etc.

The names for this field are different in different parts of the world. In the UK and US, the acronym LGBTQ+ is widely used. The terms 'lesbian', 'gay', 'bisexual', 'trans' and 'queer' are not used all around the world and definitions vary.

Apart from the terms above, there are other words and phrases that are used to define sexuality and gender identity. These words and phrases typically come from western cultures. In contrast, in non-western cultures, the range of sexual and gender identities and practices are labelled and categorized using different languages, which naturally also involve different concepts compared to Western ones.

It is concerned with the study of LGBTQ individuals' sexuality – sexual identities and behaviors – thereby validating their unique identities and experiences. This research focus is affirmative for LGBTQ individuals, as it challenges prejudiced beliefs, attitudes, and discriminatory policies and practices towards the LGBTQ community.

It also includes the study of heterosexuality – other-sex romantic attraction, preferences and behaviors, as well as heteronormativity – the traditional view of heterosexuality being the universal norm. This line of research aims to understand heterosexuality from a psychological perspective, with the additional goal of challenging heterosexuality as the norm in the field of psychology and in society as a whole.

The overall goal of LGBTQ psychology is to raise awareness of LGBTQ issues in scholarly work and psychological research. In raising this awareness, LGBT+ psychology aims to be one of the fields in which inclusive, non-heterosexist, non-genderist approaches are applied in psychological research and practice. These approaches reject the notion that heterosexuality is the 'default' and acknowledge a spectrum of genders outside of the traditional binary, allowing for more inclusive and accurate research. In line with LGBTQ psychology being an inclusive field of study and practice, it welcomes scholars or professionals from any branch of psychology with an interest in LGBTQ research.

Umbrella Terms

The 'Q' in LGBTQ is an umbrella term for identities or sexualities that do not fall within lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender identities. For example, the term non-binary is used to house many identities within the LGBTQ community. Non-binary is a term that is used to define identities that do not fall within the traditional gender binary. This means that any identities that do not classify as male or female would technically fall within the non-binary umbrella term. Identities that are usually associated with the non-binary umbrella term are genderqueer, agender, intersex, etc. Transgender is also an umbrella term for any identities that do not identify as the genders that they were assigned at birth. Non-binary can also be used within the transgender umbrella term.

History

Sexology

Sexology is a part of the historical foundation upon which LGBTQ psychology was built. The work of early sexologists, in particular those who contributed to the establishment of sexology as a scientific field of sexuality and gender ambiguity, is highly relevant and seminal to the field of LGBTQ psychology.

As previously mentioned, sexology is a scientific field of study focusing on sexuality and gender identity. In the field of sexology, a broad classification spectrum known as inversion, is used to define homosexuality. On this spectrum, early sexologists included both 'same-sex sexuality' and 'cross-gender identification' as belonging to this all-inclusive category. More contemporary sexology researchers conceptualize and categorize sexuality and gender diversity separately. In terms of LGB sexualities, this would fall under sexual diversity. As for transsexuality, this would be placed under gender diversity. Important figures in this field include Magnus Hirschfeld and Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs.

The historical emergence of 'gay affirmative' psychology

Gay affirmative psychology was first established in the 1970s. It was founded with the mission of 1) challenging the idea and view of homosexuality as a mental illness and 2) affirming the normal and healthy psychological functioning of homosexual individuals by dispelling beliefs and attitudes of homosexuality being associated with mental illness. There has been a lot of stigma surrounding the LGBTQ community which may result in feelings of self-hate. Gay affirmative therapy has been implemented with the purpose of combatting the influence that LGBTQ oppression may have had on the individuals in the community.

Following this field's mission, most of the research conducted in this area has naturally looked at the pathologization of homosexuality. In relation to this, much attention has also been placed on heterosexual and cis-gender (i.e. non-trans) individuals' lived experiences.

In the 1980s, the name gay affirmative psychology changed to lesbian and gay psychology to denote that this branch of psychology spanned both the lives and experiences of gay men and lesbian women. Later on, additional terms were included in the name of this field. Variations of LGB, LGBTQ, LGBTQ+ or LGBTQIA+ are used to refer to the field of LGBTQ psychology.

Due to the variation in the terminology to define this field, it has led to significant discussion and debate regarding which term is the most inclusive of all individuals. Though there continues to be ongoing debate surrounding the terminology used to define the field of LGBTQ psychology, this in fact highlights the field's concern over the diversity in human sexuality and gender orientation. Further, the various letters within the LGBTQ acronym indicates the diversity and variation in the scope of research that is conducted within the field – namely the types of research questions and the types of methodological approaches used to address these questions.

Traditionally, LGBTQ psychology has largely focused on researching the experiences of gay men and lesbian women meeting the following criteria:

- Young

- Caucasian

- Middle-class

- Healthy

- Residing in urban areas

Individuals may benefit from gay affirmative therapy if their therapist shares the same experience as them, but there may be a bias alongside having a therapist that is a part of the LGBTQ community. Heterosexual therapists may also hold stigma or not have the knowledge to be able to properly handle a client that belongs to the LGBTQ community.

The scope of research within the field of LGBTQ psychology has been somewhat lacking in breadth and diversity due to most of the observations regarding LGBTQ psychology to be based in behavioral research. In the past, a majority of the research done on LGBTQ psychology used physical observations and has since expanded to include psychological research. Recently, sociocultural psychologists such as Chana Etengoff, Eric M. Rodriguez and Tyler G. Lefevor have begun to explore how sexual and gender identities intersect with other minoritized identities such as religious identities (e.g., LDS, Muslim, Christian).

Overall, LGBTQ psychology is a sub-discipline of psychology that incorporates multiple perspectives and approaches regarding the populations of study, topics of research, and the theories and methodologies that inform the ways in which this research is carried out.

Mental health

LGBTQ individuals experience a significant amount of stigma and discrimination at various stages of their lives. Often this stigmatization and discrimination persists throughout their lifetime. Specific acts of stigmatization and discrimination against LGBTQ individuals include physical and sexual harassment. Hate crimes are also included. These negative experiences put LGBTQ individuals' physical and emotional well-being at risk. As a result of these experiences, LGBTQ individuals typically experience a higher frequency of mental health issues compared to those who do not belong to the LGBTQ population. More than half of the LGBTQ+ community have depression and a little less than half have PTSD or anxiety disorder.

The following list shows the different mental health issues that LGBTQ individuals may experience:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Phobic disorder

- Trauma

- Substance abuse

- Self-harming behaviors

- Suicidal tendencies and suicide

The list above is by no means complete or exhaustive, rather it shows the range and severity of the issues that LGBTQ individuals often experience. These issues usually result from a combination of negative experiences and a perpetual difficulty accepting their LGBTQ identity in an anti-LGBT society.

Suicidal tendencies and suicide are serious issues for LGBTQ youth. Compared to their non-LGBT peers, LGBTQ youth typically engage in a higher rate (around 3 to 4 times higher) of attempted suicides. People who identify as transgender are almost nine times more likely to attempt suicide than a person who does not identify in that way. A reason the number of LGBTQ+ community members who experience poor mental health is high is because it is found that many have had experiences where health care providers disrespected them. This causes one to postpone care or not return to a doctor again. Without professional help, symptoms of mental illness worsen. In school, LGBTQ youth have a higher likelihood of experiencing verbal and physical abuse due to their sexual orientation, gender identity and expression. LGBTQ youth quickly learn from these negative social experiences that they are more likely to receive negative judgment and treatment, and often rejection, from those around them. This becomes a vicious cycle in which LGBTQ youths' self-beliefs and self-perceptions are negatively reinforced by society. Evidently, the high rates of mental health issues among LGBTQ communities has been perpetuated, and continues to be so, by systemic prejudice and discrimination against LGBTQ individuals.

Nevertheless, LGBTQ individuals do not necessarily experience the same types of prejudice or discrimination, nor do they respond in the same ways to prejudice or discrimination. What is common are the reasons leading to prejudice and discrimination. In the context of LGBT-targeted prejudice and discrimination, it broadly relates to sexual orientation issues (e.g. LGB) or gender identity issues (e.g. transgender). Our basic needs as human beings include being our true selves and being accepted for who we are. Feeling loved for who we are is an important aspect of a healthy mind. Due to discrimination, LGBTQ+ individuals experience more stress and low self-esteem. Systemic prejudice and discrimination leads to LGBTQ individuals experiencing substantial amounts of stress on a long-term basis. It also influences LGBTQ individuals to internally assimilate all the negativity they receive, emphasizing the differences they have with others. This, in turn, causes LGBTQ individuals to experience guilt and shame regarding their identity, feelings and actions.

The coming out process involving LGBTQ individuals can also create a lot of added pressure from family, peers and society. This process is about LGBTQ individuals openly proclaiming their sexual orientation and/or gender identity to others. In addition, LGBTQ individuals also experience other negative outcomes, for example:

Sexual orientation and/or gender transition Internalized oppression of sexual orientation and/or gender identity

- Exclusion and ostracization

- Removed or reduced family or social support

- Facilitating mental health well-being for LGBTQ individuals is a highly pertinent matter.

The main factors in promoting positive mental health for LGBTQ individuals are as follows:

- Presence of family and peer support

- Community-based and workplace support

- Understanding, appropriate and positive feedback provided during the coming out process

- Defining, assessing and handling the social factors influencing LGBTQ individuals' health outcomes

Gender

In the past, a lot of LGBTQ studies were mainly based around the idea of sexuality, but more recently there have been more studies around the gender binary. As the community has become more inclusive and understanding of different identities over time, there has been an addition to the focus of LGBTQ psychology surrounding queer gender identities. Identities such as non-binary, transgender and gender queer may have different experiences in their coming of age and may need guidance or therapy based in those specific experiences. People that have queer identities have different experiences than people who are of homosexuality and need resources that pertain to their specific issues or needs. For example, transgender people may go through hormone therapy or face oppression that is not the same as cisgendered people who are a part of the LGBTQ community.

LGBTQ identity development in youth

There is an increasing trend of LGBTQ youth coming out and openly embracing and establishing their sexual or gender identities to people around them. Since 2000, the average age of coming out was around 14. This age compared to the average age of 16 recorded between 1996 and 1998, and 20 during the 1970s, shows that LGBTQ youth are comfortably recognizing their sexual or gender identities at an earlier age. Based on the large aggregate of research on identity development, in particular sexuality and gender identity, it appears that young people have an awareness of their LGBTQ identity from an early age. This awareness can be observed starting in childhood, specifically the feeling of being different from their peers and having non-normative appearances, behaviors and interests.

During adolescence, there are gradual shifts in young people's attitudes and behaviors regarding themselves and others. At the beginning of adolescence, young people are more aware of, and concerned about how they and others present against gender and sexuality norms. In the middle of adolescence, young people tend to hold more biased, stereotypical attitudes and show more negative behaviors towards LGBTQ individuals and topics. It is clear that the early adolescence years make it easy for LGBTQ youth who have come out to have negative or unpleasant social experiences. These experiences could involve peers intentionally excluding them from friendship groups, peers engaging in persistent, harmful acts of bullying, and more.

While there appears to be more and more LGBTQ youth coming out about their sexual and gender identities, there are also youth who do not come out and are against the idea of coming out. Thus far, psychological theory surrounding LGBTQ identity development suggests that individuals who do not come out, or are against the idea of coming out are either in denial about their identity or wish to come out but are unable to. Aside from the fact that LGBTQ youth are more vulnerable to experiencing negative social reactions and treatment as a result of coming out, there may also be other reasons for this. Firstly, the higher visibility of diverse sexualities and gender identities could influence young people in becoming more reluctant towards concretely defining their sexuality and gender identity (Savin-Williams, 2005). Young people are turning away from these types of labels in opposition of social identity labels, demonstrating the importance of their sexuality and gender identity within their personal identity. As well, LGBTQ individuals from ethnic and cultural minority groups often refrain from using sexual identity labels, which they see as westernized concepts that do not relate to them.

Schools

Current data regarding LGBTQ families and their children show an increasing number of such families, as in the United States of America, and suggests that this number is continuously increasing. Children of LGBTQ parents are at risk of being the targets of discrimination and violence against LGBTQ individuals in the education system. School has become such an unsafe place for certain LGBTQ individuals that absences have skyrocketed due to not feeling safe from violence and verbal harassment. These attacks at their identity can lead to chronic sadness and thoughts of suicide. The abuse that many LGBTQ+ students face have led to thoughts of feeling like there is something wrong with them. Therefore, this is an important issue that must be addressed to ensure the physical and psychological well-being of children from LGBT families. Apart from children of LGBT families having negative school experiences, LGBTQ parents also face challenges with regards to anti-LGBT bias and related negative behaviors that are often a part of the school climate.

LGBTQ parents can refer to the following strategies to facilitate a more safe, positive and welcoming experience in interacting with schools and school personnel: school choice, engagement, and advocacy. Many schools are not particularly inclusive of LGBTQ individuals, as anti-LGBT language is often used and cases of harassment and victimization with regards to sexual orientation or gender identity often occur. Therefore, parental choice of the school in which their child enrolls is crucial. As far as parents are able to select a school for their child, selecting a school that is inclusive of LGBTQ individuals is one way to ensure a more positive school experience for themselves and for their children. Parental engagement with schools in terms of volunteering and other forms of involvement, such as being on parent-teacher organizations, allows LGBTQ parents to be more involved in issues which may concern their child. Parents can access resources that provide information on how parents can facilitate dialogue and collaboration with teachers and schools, enabling them to become proactive advocates of their child's education and school experience.

School-based interventions are also effective in improving the experiences of children from LGBTQ families. Typically, these interventions target school climate, in particular the aspects which pertain to homophobia and transphobia. Enforcing anti-bullying/harassment policies and laws in schools can protect students from LGBTQ families from being victims of bullying and harassment. Having these policies in place generally allows students to have fewer negative experiences in school, such as a lower likelihood of mistreatment by teachers and other students. Implementing professional development opportunities for school staff on how to provide appropriate support for students from LGBTQ families will not only facilitate a more positive school experience for students, but will in turn, lead to a more positive school climate in general. Although these laws do take a step in the right direction to contribute to students feeling safe at school, another way for teachers to show their support and make them feel welcome is by putting up pride flags. This can make one feel included. Once one feels safe with the teacher to be themselves, the student will be more open to talking about their struggles. The next step is educating teachers on the resources they can use to help these children. Using an LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum where LGBTQ individuals, history and events are portrayed in a more positive manner allows students to become more aware and more accepting of LGBT-related issues. Specific ways in which LGBTQ matters can be incorporated into the curriculum include: talking about diverse families (e.g. same-sex couples and LGBTQ parents), discussing LGBTQ history (e.g. talking about significant historical events and movements related to the LGBTQ community), using LGBT-inclusive texts in class and celebrating LGBT events (e.g. LGBTQ History Month in October or LGBTQ Pride Month in June).

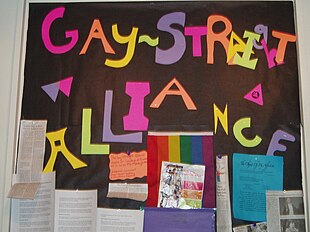

Further, organizing LGBTQ student clubs (e.g. Gay-Straight Alliances) are a positive resource and source of support for students from LGBTQ families. Studies conducted on Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) clubs have repeatedly shown a reduction in hopelessness of LGBTQ individuals who were victimized for their sexual orientation and helps decrease the risk of suicide attempts or ideation. With their inclusion of heterosexual youth, GSAs help foster a safe school environment for LGBT individuals by decreasing victimization and fear for safety. In addition to GSAs, schools that adopt safe school programs such as safe zones, diversity trainings, ally trainings, or implementation of anti-discrimination and anti-harassment policies reduce bullying and facilitate a safer school environment.

Workplace Discrimination

People that identify as a part of the LGBTQ+ community often face adversity and discrimination in the workplace. In an experimental study entitled, "Documented Evidence of Employment Discrimination & Its Effects on LGBT People," conducted by Brad Sears and Christy Mallory of the UCLA School of Law, resumes that associated applicants with a gay organization and ones that did not mention anything about the LGBTQ+ community were both sent to potential employers. Individuals' resumes that were associated with the LGBTQ+ community were less likely to receive an interview. Individuals that are able to receive an interview and get the job, furthermore, are susceptible to discrimination during work. LGBTQ+ individuals are more likely to experience discrimination in their place of work than someone who has not identified their sexuality. Discrimination often leads to health problems whether that be mental or physical. Someone who is frequently discriminated against is most likely to not show up to work, quit their job, and not put their effort into the tasks they are given due to their state of mind and the health issues that arise. To avoid workplace discrimination, many individuals will hide who they are by changing their overall appearance and keeping their sexuality a secret.

Pride

Pride celebrations allow the LGBTQ+ community to celebrate their identity. It is a day where LGBTQ+ individuals and allies come together to look back on the history and how far the community has come. They celebrate the pain that they experienced and continue to experience and they feel surrounded by people that love them for who they are. A feeling of connection and validation is important for good health and Pride is the place for people of all identities to connect. People are more likely to attend pride if they feel as though their sexual identity makes up a major part of who they are as a person. Pride is an important way to normalize being a part of the LGBTQ+ community and to make society more accepting, but there are still other ways to show that being a member of the community is not shameful.

Types of applications outside the theoretical perspective

Effective treatment methods

Expressive writing

Research has found that writing about traumatic or negative experiences (known as "expressive writing") can be an effective way to reduce psychological stress that stem from such events. When youth engaged in expressive writing on issues related to their LGBTQ identity, their mental health well-being improved. This improvement was especially significant in youth who did not have much social support, or who wrote about more serious topics, as well as in individuals who were less open about their sexualities or had not come out. Expressive writing interventions have been shown to produce positive emotional outcomes for a variety of issues, including illness, childhood trauma, and relationship stress. Writing therapy is the use of expressive writing along with other methods in a therapy setting.

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) – Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men (ESTEEM)

Cognitive-behavioural therapy focuses on changing thoughts and feelings that lead to negative behaviors, into more positive thoughts, feelings and behaviours. This treatment method is effective for a variety of mental health issues, including those related to LGBTQ identities. CBT can help reduce depression and anxiety and promote healthy coping mechanisms within LGBTQ youth. The ESTEEM program targeted stress-related thoughts and feelings that result from LGBTQ discrimination and stigma. Individuals who participated in the ESTEEM program experienced fewer depression-related thoughts and feelings and they also consumed less alcohol.

Parent and family-based LGBT treatment and education

Many LGBTQ youth may receive backlash from their families due to their sexuality or sexual identity. This may result in mental health issues such as suicide or depression. The unacceptability of an LGBTQ youth's sexuality within a household may result in mistreatment or in more severe cases, removing said person from the home. Family members not accepting their child for who they are has made it three times more likely that as an adult they will partake in the use of illegal drugs. Due to these factors, an average of 28% of LGBTQ youth have suicidal thoughts and 15%-40% make suicidal attempts each year.

Family-based treatment catering to suicidal LGBTQ adolescents where parents were given significant periods of time to process their feelings about and towards their child was found to be effective. For example, parents had time to think through how they felt about their child's LGBTQ orientation, and be made aware of how their responses towards their child could potentially reflect attitudes of devaluation. Adolescents that took part in this treatment had fewer suicidal thoughts and fewer depression-related thoughts and feelings. What is especially noteworthy is that these positive gains were sustained for many youth. While these results have been found to be effective, this method of therapy is only helpful if the family or parents are willing to go through the process of unlearning any stigma they may have against their relative being part of the LGBTQ community.

Noneffective Treatment methods

Conversion therapy (CT)

Conversion therapy focuses on altering homosexual and/or transgender individuals to heterosexual and cis-gender identities. Conversion therapy consists of a variety of approaches ranging from aversion and hormonal therapy, to religious-based techniques such as threats of eternal damnation or use of prayer. Little empirical evidence exists for CT, as most evidence is anecdotal or lacks acknowledgement of participants potentially faking or experiencing dissonance-induced rationalization. Long-term effects of CT, such as decreased overall sex drive, shame, fear, low self-esteem, and increased depression and anxiety have been observed in individuals that participated in CT programs. Due to the lack of scientific support, association with psychosocial health problems, and rejection of the practice by organizations like the American Psychiatric Association (APA), use of conversion therapy is often considered ethically problematic. Given the above concerns, there are multiple countries and various U.S. jurisdictions banning conversion therapy.