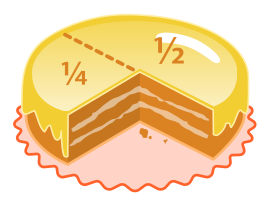

A fraction (from Latin: fractus, "broken") represents a part of a whole or, more generally, any number of equal parts. When spoken in everyday English, a fraction describes how many parts of a certain size there are, for example, one-half, eight-fifths, three-quarters. A common, vulgar, or simple fraction (examples: and ) consists of an integer numerator, displayed above a line (or before a slash like 1⁄2), and a non-zero integer denominator, displayed below (or after) that line. If these integers are positive, then the numerator represents a number of equal parts, and the denominator indicates how many of those parts make up a unit or a whole. For example, in the fraction 3/4, the numerator 3 indicates that the fraction represents 3 equal parts, and the denominator 4 indicates that 4 parts make up a whole. The picture to the right illustrates 3/4 of a cake.

Other uses for fractions are to represent ratios and division. Thus the fraction 3/4 can also be used to represent the ratio 3:4 (the ratio of the part to the whole), and the division 3 ÷ 4 (three divided by four).

We can also write negative fractions, which represent the opposite of a positive fraction. For example, if 1/2 represents a half-dollar profit, then −1/2 represents a half-dollar loss. Because of the rules of division of signed numbers (which states in part that negative divided by positive is negative), −1/2, −1/2 and 1/−2 all represent the same fraction – negative one-half. And because a negative divided by a negative produces a positive, −1/−2 represents positive one-half.

In mathematics the set of all numbers that can be expressed in the form a/b, where a and b are integers and b is not zero, is called the set of rational numbers and is represented by the symbol Q or ℚ, which stands for quotient. A number is a rational number precisely when it can be written in that form (i.e., as a common fraction). However, the word fraction can also be used to describe mathematical expressions that are not rational numbers. Examples of these usages include algebraic fractions (quotients of algebraic expressions), and expressions that contain irrational numbers, such as (see square root of 2) and π/4 (see proof that π is irrational).

Vocabulary

In a fraction, the number of equal parts being described is the numerator (from Latin: numerātor, "counter" or "numberer"), and the type or variety of the parts is the denominator (from Latin: dēnōminātor, "thing that names or designates"). As an example, the fraction 8/5 amounts to eight parts, each of which is of the type named "fifth". In terms of division, the numerator corresponds to the dividend, and the denominator corresponds to the divisor.

Informally, the numerator and denominator may be distinguished by placement alone, but in formal contexts they are usually separated by a fraction bar. The fraction bar may be horizontal (as in 1/3), oblique (as in 2/5), or diagonal (as in 4⁄9). These marks are respectively known as the horizontal bar; the virgule, slash (US), or stroke (UK); and the fraction bar, solidus, or fraction slash. In typography, fractions stacked vertically are also known as "en" or "nut fractions", and diagonal ones as "em" or "mutton fractions", based on whether a fraction with a single-digit numerator and denominator occupies the proportion of a narrow en square, or a wider em square. In traditional typefounding, a piece of type bearing a complete fraction (e.g. 1/2) was known as a "case fraction", while those representing only part of fraction were called "piece fractions".

The denominators of English fractions are generally expressed as ordinal numbers, in the plural if the numerator is not 1. (For example, 2/5 and 3/5 are both read as a number of "fifths".) Exceptions include the denominator 2, which is always read "half" or "halves", the denominator 4, which may be alternatively expressed as "quarter"/"quarters" or as "fourth"/"fourths", and the denominator 100, which may be alternatively expressed as "hundredth"/"hundredths" or "percent".

When the denominator is 1, it may be expressed in terms of "wholes" but is more commonly ignored, with the numerator read out as a whole number. For example, 3/1 may be described as "three wholes", or simply as "three". When the numerator is 1, it may be omitted (as in "a tenth" or "each quarter").

The entire fraction may be expressed as a single composition, in which case it is hyphenated, or as a number of fractions with a numerator of one, in which case they are not. (For example, "two-fifths" is the fraction 2/5 and "two fifths" is the same fraction understood as 2 instances of 1/5.) Fractions should always be hyphenated when used as adjectives. Alternatively, a fraction may be described by reading it out as the numerator "over" the denominator, with the denominator expressed as a cardinal number. (For example, 3/1 may also be expressed as "three over one".) The term "over" is used even in the case of solidus fractions, where the numbers are placed left and right of a slash mark. (For example, 1/2 may be read "one-half", "one half", or "one over two".) Fractions with large denominators that are not powers of ten are often rendered in this fashion (e.g., 1/117 as "one over one hundred seventeen"), while those with denominators divisible by ten are typically read in the normal ordinal fashion (e.g., 6/1000000 as "six-millionths", "six millionths", or "six one-millionths").

Forms of fractions

Simple, common, or vulgar fractions

A simple fraction (also known as a common fraction or vulgar fraction, where vulgar is Latin for "common") is a rational number written as a/b or , where a and b are both integers. As with other fractions, the denominator (b) cannot be zero. Examples include , , , and . The term was originally used to distinguish this type of fraction from the sexagesimal fraction used in astronomy.

Common fractions can be positive or negative, and they can be proper or improper (see below). Compound fractions, complex fractions, mixed numerals, and decimals (see below) are not common fractions; though, unless irrational, they can be evaluated to a common fraction.

- A unit fraction is a common fraction with a numerator of 1 (e.g., ). Unit fractions can also be expressed using negative exponents, as in 2−1, which represents 1/2, and 2−2, which represents 1/(22) or 1/4.

- A dyadic fraction is a common fraction in which the denominator is a power of two, e.g. .

In Unicode, precomposed fraction characters are in the Number Forms block.

Proper and improper fractions

Common fractions can be classified as either proper or improper. When the numerator and the denominator are both positive, the fraction is called proper if the numerator is less than the denominator, and improper otherwise. The concept of an "improper fraction" is a late development, with the terminology deriving from the fact that "fraction" means "a piece", so a proper fraction must be less than 1. This was explained in the 17th century textbook The Ground of Arts.

In general, a common fraction is said to be a proper fraction, if the absolute value of the fraction is strictly less than one—that is, if the fraction is greater than −1 and less than 1. It is said to be an improper fraction, or sometimes top-heavy fraction, if the absolute value of the fraction is greater than or equal to 1. Examples of proper fractions are 2/3, −3/4, and 4/9, whereas examples of improper fractions are 9/4, −4/3, and 3/3.

Reciprocals and the "invisible denominator"

The reciprocal of a fraction is another fraction with the numerator and denominator exchanged. The reciprocal of , for instance, is . The product of a fraction and its reciprocal is 1, hence the reciprocal is the multiplicative inverse of a fraction. The reciprocal of a proper fraction is improper, and the reciprocal of an improper fraction not equal to 1 (that is, numerator and denominator are not equal) is a proper fraction.

When the numerator and denominator of a fraction are equal (for example, ), its value is 1, and the fraction therefore is improper. Its reciprocal is identical and hence also equal to 1 and improper.

Any integer can be written as a fraction with the number one as denominator. For example, 17 can be written as , where 1 is sometimes referred to as the invisible denominator. Therefore, every fraction or integer, except for zero, has a reciprocal. For example. the reciprocal of 17 is .

Ratios

A ratio is a relationship between two or more numbers that can be sometimes expressed as a fraction. Typically, a number of items are grouped and compared in a ratio, specifying numerically the relationship between each group. Ratios are expressed as "group 1 to group 2 ... to group n". For example, if a car lot had 12 vehicles, of which

- 2 are white,

- 6 are red, and

- 4 are yellow,

then the ratio of red to white to yellow cars is 6 to 2 to 4. The ratio of yellow cars to white cars is 4 to 2 and may be expressed as 4:2 or 2:1.

A ratio is often converted to a fraction when it is expressed as a ratio to the whole. In the above example, the ratio of yellow cars to all the cars on the lot is 4:12 or 1:3. We can convert these ratios to a fraction, and say that 4/12 of the cars or 1/3 of the cars in the lot are yellow. Therefore, if a person randomly chose one car on the lot, then there is a one in three chance or probability that it would be yellow.

Decimal fractions and percentages

A decimal fraction is a fraction whose denominator is not given explicitly, but is understood to be an integer power of ten. Decimal fractions are commonly expressed using decimal notation in which the implied denominator is determined by the number of digits to the right of a decimal separator, the appearance of which (e.g., a period, an interpunct (·), a comma) depends on the locale (for examples, see decimal separator). Thus, for 0.75 the numerator is 75 and the implied denominator is 10 to the second power, namely, 100, because there are two digits to the right of the decimal separator. In decimal numbers greater than 1 (such as 3.75), the fractional part of the number is expressed by the digits to the right of the decimal (with a value of 0.75 in this case). 3.75 can be written either as an improper fraction, 375/100, or as a mixed number, .

Decimal fractions can also be expressed using scientific notation with negative exponents, such as 6.023×10−7, which represents 0.0000006023. The 10−7 represents a denominator of 107. Dividing by 107 moves the decimal point 7 places to the left.

Decimal fractions with infinitely many digits to the right of the decimal separator represent an infinite series. For example, 1/3 = 0.333... represents the infinite series 3/10 + 3/100 + 3/1000 + ....

Another kind of fraction is the percentage (from Latin: per centum, meaning "per hundred", represented by the symbol %), in which the implied denominator is always 100. Thus, 51% means 51/100. Percentages greater than 100 or less than zero are treated in the same way, e.g. 311% equals 311/100, and −27% equals −27/100.

The related concept of permille or parts per thousand (ppt) has an implied denominator of 1000, while the more general parts-per notation, as in 75 parts per million (ppm), means that the proportion is 75/1,000,000.

Whether common fractions or decimal fractions are used is often a matter of taste and context. Common fractions are used most often when the denominator is relatively small. By mental calculation, it is easier to multiply 16 by 3/16 than to do the same calculation using the fraction's decimal equivalent (0.1875). And it is more accurate to multiply 15 by 1/3, for example, than it is to multiply 15 by any decimal approximation of one third. Monetary values are commonly expressed as decimal fractions with denominator 100, i.e., with two decimals, for example $3.75. However, as noted above, in pre-decimal British currency, shillings and pence were often given the form (but not the meaning) of a fraction, as, for example, "3/6" (read "three and six") meaning 3 shillings and 6 pence, and having no relationship to the fraction 3/6.

Mixed numbers

A mixed numeral (also called a mixed fraction or mixed number) is a traditional denotation of the sum of a non-zero integer and a proper fraction (having the same sign). It is used primarily in measurement: inches, for example. Scientific measurements almost invariably use decimal notation rather than mixed numbers. The sum can be implied without the use of a visible operator such as the appropriate "+". For example, in referring to two entire cakes and three quarters of another cake, the numerals denoting the integer part and the fractional part of the cakes can be written next to each other as instead of the unambiguous notation Negative mixed numerals, as in , are treated like Any such sum of a whole plus a part can be converted to an improper fraction by applying the rules of adding unlike quantities.

This tradition is, formally, in conflict with the notation in algebra where adjacent symbols, without an explicit infix operator, denote a product. In the expression , the "understood" operation is multiplication. If x is replaced by, for example, the fraction , the "understood" multiplication needs to be replaced by explicit multiplication, to avoid the appearance of a mixed number.

When multiplication is intended, may be written as

- or or

An improper fraction can be converted to a mixed number as follows:

- Using Euclidean division (division with remainder), divide the numerator by the denominator. In the example, , divide 11 by 4. 11 ÷ 4 = 2 remainder 3.

- The quotient (without the remainder) becomes the whole number part of the mixed number. The remainder becomes the numerator of the fractional part. In the example, 2 is the whole number part and 3 is the numerator of the fractional part.

- The new denominator is the same as the denominator of the improper fraction. In the example, it is 4. Thus, .

Historical notions

Egyptian fraction

An Egyptian fraction is the sum of distinct positive unit fractions, for example . This definition derives from the fact that the ancient Egyptians expressed all fractions except , and in this manner. Every positive rational number can be expanded as an Egyptian fraction. For example, can be written as Any positive rational number can be written as a sum of unit fractions in infinitely many ways. Two ways to write are and .

Complex and compound fractions

In a complex fraction, either the numerator, or the denominator, or both, is a fraction or a mixed number, corresponding to division of fractions. For example, and are complex fractions. To reduce a complex fraction to a simple fraction, treat the longest fraction line as representing division. For example:

If, in a complex fraction, there is no unique way to tell which fraction lines takes precedence, then this expression is improperly formed, because of ambiguity. So 5/10/20/40 is not a valid mathematical expression, because of multiple possible interpretations, e.g. as

- or as

A compound fraction is a fraction of a fraction, or any number of fractions connected with the word of, corresponding to multiplication of fractions. To reduce a compound fraction to a simple fraction, just carry out the multiplication (see the section on multiplication). For example, of is a compound fraction, corresponding to . The terms compound fraction and complex fraction are closely related and sometimes one is used as a synonym for the other. (For example, the compound fraction is equivalent to the complex fraction .)

Nevertheless, "complex fraction" and "compound fraction" may both be considered outdated and now used in no well-defined manner, partly even taken synonymously for each other or for mixed numerals. They have lost their meaning as technical terms and the attributes "complex" and "compound" tend to be used in their every day meaning of "consisting of parts".

Arithmetic with fractions

Like whole numbers, fractions obey the commutative, associative, and distributive laws, and the rule against division by zero.

Equivalent fractions

Multiplying the numerator and denominator of a fraction by the same (non-zero) number results in a fraction that is equivalent to the original fraction. This is true because for any non-zero number , the fraction equals . Therefore, multiplying by is the same as multiplying by one, and any number multiplied by one has the same value as the original number. By way of an example, start with the fraction . When the numerator and denominator are both multiplied by 2, the result is , which has the same value (0.5) as . To picture this visually, imagine cutting a cake into four pieces; two of the pieces together () make up half the cake ().

Simplifying (reducing) fractions

Dividing the numerator and denominator of a fraction by the same non-zero number yields an equivalent fraction: if the numerator and the denominator of a fraction are both divisible by a number (called a factor) greater than 1, then the fraction can be reduced to an equivalent fraction with a smaller numerator and a smaller denominator. For example, if both the numerator and the denominator of the fraction are divisible by then they can be written as and and the fraction becomes , which can be reduced by dividing both the numerator and denominator by to give the reduced fraction

If one takes for c the greatest common divisor of the numerator and the denominator, one gets the equivalent fraction whose numerator and denominator have the lowest absolute values. One says that the fraction has been reduced to its lowest terms.

If the numerator and the denominator do not share any factor greater than 1, the fraction is already reduced to its lowest terms, and it is said to be irreducible, reduced, or in simplest terms. For example, is not in lowest terms because both 3 and 9 can be exactly divided by 3. In contrast, is in lowest terms—the only positive integer that goes into both 3 and 8 evenly is 1.

Using these rules, we can show that , for example.

As another example, since the greatest common divisor of 63 and 462 is 21, the fraction can be reduced to lowest terms by dividing the numerator and denominator by 21:

The Euclidean algorithm gives a method for finding the greatest common divisor of any two integers.

Comparing fractions

Comparing fractions with the same positive denominator yields the same result as comparing the numerators:

- because 3 > 2, and the equal denominators are positive.

If the equal denominators are negative, then the opposite result of comparing the numerators holds for the fractions:

If two positive fractions have the same numerator, then the fraction with the smaller denominator is the larger number. When a whole is divided into equal pieces, if fewer equal pieces are needed to make up the whole, then each piece must be larger. When two positive fractions have the same numerator, they represent the same number of parts, but in the fraction with the smaller denominator, the parts are larger.

One way to compare fractions with different numerators and denominators is to find a common denominator. To compare and , these are converted to and (where the dot signifies multiplication and is an alternative symbol to ×). Then bd is a common denominator and the numerators ad and bc can be compared. It is not necessary to determine the value of the common denominator to compare fractions – one can just compare ad and bc, without evaluating bd, e.g., comparing ? gives .

For the more laborious question ? multiply top and bottom of each fraction by the denominator of the other fraction, to get a common denominator, yielding ? . It is not necessary to calculate – only the numerators need to be compared. Since 5×17 (= 85) is greater than 4×18 (= 72), the result of comparing is .

Because every negative number, including negative fractions, is less than zero, and every positive number, including positive fractions, is greater than zero, it follows that any negative fraction is less than any positive fraction. This allows, together with the above rules, to compare all possible fractions.

Addition

The first rule of addition is that only like quantities can be added; for example, various quantities of quarters. Unlike quantities, such as adding thirds to quarters, must first be converted to like quantities as described below: Imagine a pocket containing two quarters, and another pocket containing three quarters; in total, there are five quarters. Since four quarters is equivalent to one (dollar), this can be represented as follows:

- .

Adding unlike quantities

To add fractions containing unlike quantities (e.g. quarters and thirds), it is necessary to convert all amounts to like quantities. It is easy to work out the chosen type of fraction to convert to; simply multiply together the two denominators (bottom number) of each fraction. In case of an integer number apply the invisible denominator

For adding quarters to thirds, both types of fraction are converted to twelfths, thus:

Consider adding the following two quantities:

First, convert into fifteenths by multiplying both the numerator and denominator by three: . Since equals 1, multiplication by does not change the value of the fraction.

Second, convert into fifteenths by multiplying both the numerator and denominator by five: .

Now it can be seen that:

is equivalent to:

This method can be expressed algebraically:

This algebraic method always works, thereby guaranteeing that the sum of simple fractions is always again a simple fraction. However, if the single denominators contain a common factor, a smaller denominator than the product of these can be used. For example, when adding and the single denominators have a common factor and therefore, instead of the denominator 24 (4 × 6), the halved denominator 12 may be used, not only reducing the denominator in the result, but also the factors in the numerator.

The smallest possible denominator is given by the least common multiple of the single denominators, which results from dividing the rote multiple by all common factors of the single denominators. This is called the least common denominator.

Subtraction

The process for subtracting fractions is, in essence, the same as that of adding them: find a common denominator, and change each fraction to an equivalent fraction with the chosen common denominator. The resulting fraction will have that denominator, and its numerator will be the result of subtracting the numerators of the original fractions. For instance,

Multiplication

Multiplying a fraction by another fraction

To multiply fractions, multiply the numerators and multiply the denominators. Thus:

To explain the process, consider one third of one quarter. Using the example of a cake, if three small slices of equal size make up a quarter, and four quarters make up a whole, twelve of these small, equal slices make up a whole. Therefore, a third of a quarter is a twelfth. Now consider the numerators. The first fraction, two thirds, is twice as large as one third. Since one third of a quarter is one twelfth, two thirds of a quarter is two twelfth. The second fraction, three quarters, is three times as large as one quarter, so two thirds of three quarters is three times as large as two thirds of one quarter. Thus two thirds times three quarters is six twelfths.

A short cut for multiplying fractions is called "cancellation". Effectively the answer is reduced to lowest terms during multiplication. For example:

A two is a common factor in both the numerator of the left fraction and the denominator of the right and is divided out of both. Three is a common factor of the left denominator and right numerator and is divided out of both.

Multiplying a fraction by a whole number

Since a whole number can be rewritten as itself divided by 1, normal fraction multiplication rules can still apply.

This method works because the fraction 6/1 means six equal parts, each one of which is a whole.

Multiplying mixed numbers

When multiplying mixed numbers, it is considered preferable to convert the mixed number into an improper fraction. For example:

In other words, is the same as , making 11 quarters in total (because 2 cakes, each split into quarters makes 8 quarters total) and 33 quarters is , since 8 cakes, each made of quarters, is 32 quarters in total.

Division

To divide a fraction by a whole number, you may either divide the numerator by the number, if it goes evenly into the numerator, or multiply the denominator by the number. For example, equals and also equals , which reduces to . To divide a number by a fraction, multiply that number by the reciprocal of that fraction. Thus, .

Converting between decimals and fractions

To change a common fraction to a decimal, do a long division of the decimal representations of the numerator by the denominator (this is idiomatically also phrased as "divide the denominator into the numerator"), and round the answer to the desired accuracy. For example, to change 1/4 to a decimal, divide 1.00 by 4 ("4 into 1.00"), to obtain 0.25. To change 1/3 to a decimal, divide 1.000... by 3 ("3 into 1.000..."), and stop when the desired accuracy is obtained, e.g., at 4 decimals with 0.3333. The fraction 1/4 can be written exactly with two decimal digits, while the fraction 1/3 cannot be written exactly as a decimal with a finite number of digits. To change a decimal to a fraction, write in the denominator a 1 followed by as many zeroes as there are digits to the right of the decimal point, and write in the numerator all the digits of the original decimal, just omitting the decimal point. Thus

Converting repeating decimals to fractions

Decimal numbers, while arguably more useful to work with when performing calculations, sometimes lack the precision that common fractions have. Sometimes an infinite repeating decimal is required to reach the same precision. Thus, it is often useful to convert repeating decimals into fractions.

A conventional way to indicate a repeating decimal is to place a bar (known as a vinculum) over the digits that repeat, for example 0.789 = 0.789789789... For repeating patterns that begin immediately after the decimal point, the result of the conversion is the fraction with the pattern as a numerator, and the same number of nines as a denominator. For example:

- 0.5 = 5/9

- 0.62 = 62/99

- 0.264 = 264/999

- 0.6291 = 6291/9999

If leading zeros precede the pattern, the nines are suffixed by the same number of trailing zeros:

- 0.05 = 5/90

- 0.000392 = 392/999000

- 0.0012 = 12/9900

If a non-repeating set of decimals precede the pattern (such as 0.1523987), one may write the number as the sum of the non-repeating and repeating parts, respectively:

- 0.1523 + 0.0000987

Then, convert both parts to fractions, and add them using the methods described above:

- 1523 / 10000 + 987 / 9990000 = 1522464 / 9990000

Alternatively, algebra can be used, such as below:

- Let x = the repeating decimal:

- x = 0.1523987

- Multiply both sides by the power of 10 just great enough (in this case 104) to move the decimal point just before the repeating part of the decimal number:

- 10,000x = 1,523.987

- Multiply both sides by the power of 10 (in this case 103) that is the same as the number of places that repeat:

- 10,000,000x = 1,523,987.987

- Subtract the two equations from each other (if a = b and c = d, then a − c = b − d):

- 10,000,000x − 10,000x = 1,523,987.987 − 1,523.987

- Continue the subtraction operation to clear the repeating decimal:

- 9,990,000x = 1,523,987 − 1,523

- = 1,522,464

- Divide both sides by 9,990,000 to represent x as a fraction

- x = 1522464/9990000

Fractions in abstract mathematics

In addition to being of great practical importance, fractions are also studied by mathematicians, who check that the rules for fractions given above are consistent and reliable. Mathematicians define a fraction as an ordered pair of integers and for which the operations addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are defined as follows:

These definitions agree in every case with the definitions given above; only the notation is different. Alternatively, instead of defining subtraction and division as operations, the "inverse" fractions with respect to addition and multiplication might be defined as:

Furthermore, the relation, specified as

is an equivalence relation of fractions. Each fraction from one equivalence class may be considered as a representative for the whole class, and each whole class may be considered as one abstract fraction. This equivalence is preserved by the above defined operations, i.e., the results of operating on fractions are independent of the selection of representatives from their equivalence class. Formally, for addition of fractions

- and imply

and similarly for the other operations.

In the case of fractions of integers, the fractions a/b with a and b coprime and b > 0 are often taken as uniquely determined representatives for their equivalent fractions, which are considered to be the same rational number. This way the fractions of integers make up the field of the rational numbers.

More generally, a and b may be elements of any integral domain R, in which case a fraction is an element of the field of fractions of R. For example, polynomials in one indeterminate, with coefficients from some integral domain D, are themselves an integral domain, call it P. So for a and b elements of P, the generated field of fractions is the field of rational fractions (also known as the field of rational functions).

Algebraic fractions

An algebraic fraction is the indicated quotient of two algebraic expressions. As with fractions of integers, the denominator of an algebraic fraction cannot be zero. Two examples of algebraic fractions are and . Algebraic fractions are subject to the same field properties as arithmetic fractions.

If the numerator and the denominator are polynomials, as in , the algebraic fraction is called a rational fraction (or rational expression). An irrational fraction is one that is not rational, as, for example, one that contains the variable under a fractional exponent or root, as in .

The terminology used to describe algebraic fractions is similar to that used for ordinary fractions. For example, an algebraic fraction is in lowest terms if the only factors common to the numerator and the denominator are 1 and −1. An algebraic fraction whose numerator or denominator, or both, contain a fraction, such as , is called a complex fraction.

The field of rational numbers is the field of fractions of the integers, while the integers themselves are not a field but rather an integral domain. Similarly, the rational fractions with coefficients in a field form the field of fractions of polynomials with coefficient in that field. Considering the rational fractions with real coefficients, radical expressions representing numbers, such as are also rational fractions, as are a transcendental numbers such as since all of and are real numbers, and thus considered as coefficients. These same numbers, however, are not rational fractions with integer coefficients.

The term partial fraction is used when decomposing rational fractions into sums of simpler fractions. For example, the rational fraction can be decomposed as the sum of two fractions: This is useful for the computation of antiderivatives of rational functions (see partial fraction decomposition for more).

Radical expressions

A fraction may also contain radicals in the numerator or the denominator. If the denominator contains radicals, it can be helpful to rationalize it (compare Simplified form of a radical expression), especially if further operations, such as adding or comparing that fraction to another, are to be carried out. It is also more convenient if division is to be done manually. When the denominator is a monomial square root, it can be rationalized by multiplying both the top and the bottom of the fraction by the denominator:

The process of rationalization of binomial denominators involves multiplying the top and the bottom of a fraction by the conjugate of the denominator so that the denominator becomes a rational number. For example:

Even if this process results in the numerator being irrational, like in the examples above, the process may still facilitate subsequent manipulations by reducing the number of irrationals one has to work with in the denominator.

Typographical variations

In computer displays and typography, simple fractions are sometimes printed as a single character, e.g. ½ (one half). See the article on Number Forms for information on doing this in Unicode.

Scientific publishing distinguishes four ways to set fractions, together with guidelines on use:

- Special fractions: fractions that are presented as a single character with a slanted bar, with roughly the same height and width as other characters in the text. Generally used for simple fractions, such as: ½, ⅓, ⅔, ¼, and ¾. Since the numerals are smaller, legibility can be an issue, especially for small-sized fonts. These are not used in modern mathematical notation, but in other contexts.

- Case fractions: similar to special fractions, these are rendered as a single typographical character, but with a horizontal bar, thus making them upright. An example would be , but rendered with the same height as other characters. Some sources include all rendering of fractions as case fractions if they take only one typographical space, regardless of the direction of the bar.

- Shilling or solidus fractions: 1/2, so called because this notation was used for pre-decimal British currency (£sd), as in "2/6" for a half crown, meaning two shillings and six pence. While the notation "two shillings and six pence" did not represent a fraction, the forward slash is now used in fractions, especially for fractions inline with prose (rather than displayed), to avoid uneven lines. It is also used for fractions within fractions (complex fractions) or within exponents to increase legibility. Fractions written this way, also known as piece fractions, are written all on one typographical line, but take 3 or more typographical spaces.

- Built-up fractions: . This notation uses two or more lines of ordinary text and results in a variation in spacing between lines when included within other text. While large and legible, these can be disruptive, particularly for simple fractions or within complex fractions.

History

The earliest fractions were reciprocals of integers: ancient symbols representing one part of two, one part of three, one part of four, and so on. The Egyptians used Egyptian fractions c. 1000 BC. About 4000 years ago, Egyptians divided with fractions using slightly different methods. They used least common multiples with unit fractions. Their methods gave the same answer as modern methods. The Egyptians also had a different notation for dyadic fractions in the Akhmim Wooden Tablet and several Rhind Mathematical Papyrus problems.

The Greeks used unit fractions and (later) continued fractions. Followers of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras (c. 530 BC) discovered that the square root of two cannot be expressed as a fraction of integers. (This is commonly though probably erroneously ascribed to Hippasus of Metapontum, who is said to have been executed for revealing this fact.) In 150 BC Jain mathematicians in India wrote the "Sthananga Sutra", which contains work on the theory of numbers, arithmetical operations, and operations with fractions.

A modern expression of fractions known as bhinnarasi seems to have originated in India in the work of Aryabhatta (c. AD 500), Brahmagupta (c. 628), and Bhaskara (c. 1150). Their works form fractions by placing the numerators (Sanskrit: amsa) over the denominators (cheda), but without a bar between them. In Sanskrit literature, fractions were always expressed as an addition to or subtraction from an integer. The integer was written on one line and the fraction in its two parts on the next line. If the fraction was marked by a small circle ⟨०⟩ or cross ⟨+⟩, it is subtracted from the integer; if no such sign appears, it is understood to be added. For example, Bhaskara I writes:

- ६ १ २

- १ १ १०

- ४ ५ ९

which is the equivalent of

- 6 1 2

- 1 1 −1

- 4 5 9

and would be written in modern notation as 61/4, 11/5, and 2 − 1/9 (i.e., 18/9).

The horizontal fraction bar is first attested in the work of Al-Hassār (fl. 1200), a Muslim mathematician from Fez, Morocco, who specialized in Islamic inheritance jurisprudence. In his discussion he writes: "for example, if you are told to write three-fifths and a third of a fifth, write thus, ". The same fractional notation—with the fraction given before the integer—appears soon after in the work of Leonardo Fibonacci in the 13th century.

In discussing the origins of decimal fractions, Dirk Jan Struik states:

The introduction of decimal fractions as a common computational practice can be dated back to the Flemish pamphlet De Thiende, published at Leyden in 1585, together with a French translation, La Disme, by the Flemish mathematician Simon Stevin (1548–1620), then settled in the Northern Netherlands. It is true that decimal fractions were used by the Chinese many centuries before Stevin and that the Persian astronomer Al-Kāshī used both decimal and sexagesimal fractions with great ease in his Key to arithmetic (Samarkand, early fifteenth century).

While the Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī claimed to have discovered decimal fractions himself in the 15th century, J. Lennart Berggren notes that he was mistaken, as decimal fractions were first used five centuries before him by the Baghdadi mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi as early as the 10th century.

In formal education

Pedagogical tools

In primary schools, fractions have been demonstrated through Cuisenaire rods, Fraction Bars, fraction strips, fraction circles, paper (for folding or cutting), pattern blocks, pie-shaped pieces, plastic rectangles, grid paper, dot paper, geoboards, counters and computer software.

Documents for teachers

Several states in the United States have adopted learning trajectories from the Common Core State Standards Initiative's guidelines for mathematics education. Aside from sequencing the learning of fractions and operations with fractions, the document provides the following definition of a fraction: "A number expressible in the form / where is a whole number and is a positive whole number. (The word fraction in these standards always refers to a non-negative number.)" The document itself also refers to negative fractions.