Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. A distinction may be made between exclusive monotheism, in which the one God is a singular existence, and both inclusive and pluriform monotheism, in which multiple gods or godly forms are recognized, but each are postulated as extensions of the same God.

Monotheism is distinguished from henotheism, a religious system in which the believer worships one God without denying that others may worship different gods with equal validity, and monolatrism, the recognition of the existence of many gods but with the consistent worship of only one deity. The term monolatry was perhaps first used by Julius Wellhausen.

Monotheism characterizes the traditions of Bábism, the Baháʼí Faith, Cheondoism, Christianity, Deism, Druzism, Eckankar, Sikhism, some sects of Hinduism (such as Shaivism and Vaishnavism), Islam, Judaism, Samaritanism, Mandaeism, Rastafari, Seicho-no-Ie, Tenrikyo, Yazidism, and Atenism. Elements of monotheistic thought are found in early religions such as Zoroastrianism, ancient Chinese religion, and Yahwism.

Etymology

The word monotheism comes from the Greek μόνος (monos) meaning "single" and θεός (theos) meaning "god". The English term was first used by Henry More (1614–1687).

History

Quasi-monotheistic claims of the existence of a universal deity date to the Late Bronze Age, with Akhenaten's Great Hymn to the Aten from the 14th century BCE.

In the Iron-Age South Asian Vedic period, a possible inclination towards monotheism emerged. The Rigveda exhibits notions of monism of the Brahman, particularly in the comparatively late tenth book, which is dated to the early Iron Age, e.g. in the Nasadiya Sukta. Later, ancient Hindu theology was monist, but was not strictly monotheistic in worship because it still maintained the existence of many gods, who were envisioned as aspects of one supreme God, Brahman.

In China, the orthodox faith system held by most dynasties since at least the Shang Dynasty (1766 BCE) until the modern period centered on the worship of Shangdi (literally "Above Sovereign", generally translated as "God") or Heaven as an omnipotent force. However, this faith system was not truly monotheistic since other lesser gods and spirits, which varied with locality, were also worshipped along with Shangdi. Still, later variants such as Mohism (470 BCE–c.391 BCE) approached true monotheism, teaching that the function of lesser gods and ancestral spirits is merely to carry out the will of Shangdi, akin to the angels in Abrahamic religions which in turn counts as only one god.

Since the sixth century BCE, Zoroastrians have believed in the supremacy of one God above all: Ahura Mazda as the "Maker of All" and the first being before all others. While this is true, Zoroastrianism is not considered monotheistic as it has a dualistic cosmology, with a pantheon of lesser "gods" or Yazats, such as Mithra, who are worshipped as lesser divinities alongside Ahura Mazda. Along with this, Ahura Mazda is not fully omnipotent engaged in a constant struggle with Angra Mainyu, the force of evil, although good will ultimately overcome evil.

Post-exilic Judaism, after the late 6th century BCE, was the first religion to conceive the notion of a personal monotheistic God within a monist context. The concept of ethical monotheism, which holds that morality stems from God alone and that its laws are unchanging, first occurred in Judaism, but is now a core tenet of most modern monotheistic religions, including Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, and Baháʼí Faith.

Also from the 6th century BCE, Thales (followed by other Monists, such as Anaximander, Anaximenes, Heraclitus, Parmenides) proposed that nature can be explained by reference to a single unitary principle that pervades everything. Numerous ancient Greek philosophers, including Xenophanes of Colophon and Antisthenes, believed in a similar polytheistic monism that bore some similarities to monotheism. The first known reference to a unitary God is Plato's Demiurge (divine Craftsman), followed by Aristotle's unmoved mover, both of which would profoundly influence Jewish and Christian theology.

According to Jewish, Christian and Islamic tradition, monotheism was the original religion of humanity; this original religion is sometimes referred to as "the Adamic religion", or, in the terms of Andrew Lang, the "Urreligion". Scholars of religion largely abandoned that view in the 19th century in favour of an evolutionary progression from animism via polytheism to monotheism, but by 1974, this theory was less widely held, and a modified view similar to Lang's became more prominent. Austrian anthropologist Wilhelm Schmidt had postulated an Urmonotheismus, "original" or "primitive monotheism" in the 1910s. It was objected that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam had grown up in opposition to polytheism as had Greek philosophical monotheism. More recently, Karen Armstrong and other authors have returned to the idea of an evolutionary progression beginning with animism, which developed into polytheism, which developed into henotheism, which developed into monolatry, which developed into true monotheism.

Africa

Indigenous African religion

The Tikar people of Cameroon have a traditional spirituality that emphasizes the worship of a single god, Nyuy.

The Himba people of Namibia practice a form of monotheistic panentheism, and worship the god Mukuru. The deceased ancestors of the Himba and Herero are subservient to him, acting as intermediaries.

The Igbo people practice a form of monotheism called Odinani. Odinani has monotheistic and panentheistic attributes, having a single God as the source of all things. Although a pantheon of spirits exists, these are lesser spirits prevalent in Odinani expressly serving as elements of Chineke (or Chukwu), the supreme being or high god.

Waaq is the name of a singular God in the traditional religion of many Cushitic people in the Horn of Africa, denoting an early monotheistic religion. However this religion was mostly replaced with the Abrahamic religions. Some (approximately 3%) of Oromo still follow this traditional monotheistic religion called Waaqeffanna in Oromo.

Ancient Egypt

Atenism

Amenhotep IV initially introduced Atenism in Year 5 of his reign (1348/1346 BCE) during the 18th dynasty of the New Kingdom. He raised Aten, once a relatively obscure Egyptian solar deity representing the disk of the sun, to the status of Supreme God in the Egyptian pantheon. To emphasise the change, Aten's name was written in the cartouche form normally reserved for Pharaohs, an innovation of Atenism. This religious reformation appears to coincide with the proclamation of a Sed festival, a sort of royal jubilee intended to reinforce the Pharaoh's divine powers of kingship. Traditionally held in the thirtieth year of the Pharaoh's reign, this possibly was a festival in honour of Amenhotep III, who some Egyptologists think had a coregency with his son Amenhotep IV of two to twelve years.

Year 5 is believed to mark the beginning of Amenhotep IV's construction of a new capital, Akhetaten (Horizon of the Aten), at the site known today as Amarna. Evidence of this appears on three of the boundary stelae used to mark the boundaries of this new capital. At this time, Amenhotep IV officially changed his name to Akhenaten (Agreeable to Aten) as evidence of his new worship. The date given for the event has been estimated to fall around January 2 of that year. In Year 7 of his reign (1346/1344 BCE), the capital was moved from Thebes to Akhetaten (near modern Amarna), though construction of the city seems to have continued for two more years. In shifting his court from the traditional ceremonial centres Akhenaten was signalling a dramatic transformation in the focus of religious and political power.

The move separated the Pharaoh and his court from the influence of the priesthood and from the traditional centres of worship, but his decree had deeper religious significance too—taken in conjunction with his name change, it is possible that the move to Amarna was also meant as a signal of Akhenaten's symbolic death and rebirth. It may also have coincided with the death of his father and the end of the coregency. In addition to constructing a new capital in honor of Aten, Akhenaten also oversaw the construction of some of the most massive temple complexes in ancient Egypt, including one at Karnak and one at Thebes, close to the old temple of Amun.

In Year 9 (1344/1342 BCE), Akhenaten declared a more radical version of his new religion, declaring Aten not merely the supreme god of the Egyptian pantheon, but the only God of Egypt, with himself as the sole intermediary between the Aten and the Egyptian people. Key features of Atenism included a ban on idols and other images of the Aten, with the exception of a rayed solar disc, in which the rays (commonly depicted ending in hands) appear to represent the unseen spirit of Aten. Akhenaten made it however clear that the image of the Aten only represented the god, but that the god transcended creation and so could not be fully understood or represented. Aten was addressed by Akhenaten in prayers, such as the Great Hymn to the Aten: "O Sole God beside whom there is none".

The details of Atenist theology are still unclear. The exclusion of all but one god and the prohibition of idols was a radical departure from Egyptian tradition, but scholars see Akhenaten as a practitioner of monolatry rather than monotheism, as he did not actively deny the existence of other gods; he simply refrained from worshiping any but Aten. Akhenaten associated Aten with Ra and put forward the eminence of Aten as the renewal of the kingship of Ra.

Under Akhenaten's successors, Egypt reverted to its traditional religion, and Akhenaten himself came to be reviled as a heretic.

Other monotheistic traditions

Some Egyptian ethical texts believed in only a single god ruling over the universe.

Americas

Native American religion

Native American religions may be monotheistic, polytheistic, henotheistic, animistic, or some combination thereof. Cherokee religion, for example, is monotheist as well as pantheist.

The Great Spirit, called Wakan Tanka among the Sioux, and Gitche Manitou in Algonquian, is a conception of universal spiritual force, or supreme being prevalent among some Native American and First Nation cultures. According to Lakota activist Russell Means a better translation of Wakan Tanka is the Great Mystery.

Some researchers have interpreted Aztec philosophy as fundamentally monotheistic or panentheistic. While the populace at large believed in a polytheistic pantheon, Aztec priests and nobles might have come to an interpretation of Teotl as a single universal force with many facets. There has been criticism to this idea, however, most notably that many assertions of this supposed monotheism might actually come from post-Conquistador bias, imposing an Antiquity pagan model onto the Aztec.

Eastern Asia

Chinese religion

The orthodox faith system held by most dynasties of China since at least the Shang Dynasty (1766 BCE) until the modern period centered on the worship of Shangdi (literally "Above Sovereign", generally translated as "High-god") or Heaven as a supreme being, standing above other gods. This faith system pre-dated the development of Confucianism and Taoism and the introduction of Buddhism and Christianity. It has some features of monotheism in that Heaven is seen as an omnipotent entity, a noncorporeal force with a personality transcending the world. However, this faith system was not truly monotheistic since other lesser gods and spirits, which varied with locality, were also worshiped along with Shangdi. Still, later variants such as Mohism (470 BCE–c.391 BCE) approached true monotheism, teaching that the function of lesser gods and ancestral spirits is merely to carry out the will of Shangdi. In Mozi's Will of Heaven (天志), he writes:

I know Heaven loves men dearly not without reason. Heaven ordered the sun, the moon, and the stars to enlighten and guide them. Heaven ordained the four seasons, Spring, Autumn, Winter, and Summer, to regulate them. Heaven sent down snow, frost, rain, and dew to grow the five grains and flax and silk that so the people could use and enjoy them. Heaven established the hills and rivers, ravines and valleys, and arranged many things to minister to man's good or bring him evil. He appointed the dukes and lords to reward the virtuous and punish the wicked, and to gather metal and wood, birds and beasts, and to engage in cultivating the five grains and flax and silk to provide for the people's food and clothing. This has been so from antiquity to the present.

且吾所以知天之愛民之厚者有矣,曰以磨為日月星辰,以昭道之;制為四時春秋冬夏,以紀綱之;雷降雪霜雨露,以長遂五穀麻絲,使民得而財利之;列為山川谿谷,播賦百事,以臨司民之善否;為王公侯伯,使之賞賢而罰暴;賊金木鳥獸,從事乎五穀麻絲,以為民衣食之財。自古及今,未嘗不有此也。

— Will of Heaven, Chapter 27, Paragraph 6, ca. 5th century BCE

Worship of Shangdi and Heaven in ancient China includes the erection of shrines, the last and greatest being the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, and the offering of prayers. The ruler of China in every Chinese dynasty would perform annual sacrificial rituals to Shangdi, usually by slaughtering a completely healthy bull as sacrifice. Although its popularity gradually diminished after the advent of Taoism and Buddhism, among other religions, its concepts remained in use throughout the pre-modern period and have been incorporated in later religions in China, including terminology used by early Christians in China. Despite the rising of non-theistic and pantheistic spirituality contributed by Taoism and Buddhism, Shangdi was still praised up until the end of the Qing Dynasty as the last ruler of the Qing declared himself son of heaven.

In the 19th century in the Guangdong region, monotheism was well-known and popular in Chinese folk religion.

Tengrism

Tengrism or Tangrism (sometimes stylized as Tengriism), occasionally referred to as Tengrianism, is a modern term for a Central Asian religion characterized by features of shamanism, animism, totemism, both polytheism and monotheism, and ancestor worship. Historically, it was the prevailing religion of the Bulgars, Turks, Mongols, and Hungarians, as well as the Xiongnu and the Huns. It was the state religion of the six ancient Turkic states: Avar Khaganate, Old Great Bulgaria, First Bulgarian Empire, Göktürks Khaganate, Eastern Tourkia and Western Turkic Khaganate. In Irk Bitig, Tengri is mentioned as Türük Tängrisi (God of Turks). The term is perceived among Turkic peoples as a national religion.

In Chinese and Turco-Mongol traditions, the Supreme God is commonly referred to as the ruler of Heaven, or the Sky Lord granted with omnipotent powers, but it has largely diminished in those regions due to ancestor worship, Taoism's pantheistic views and Buddhism's rejection of a creator God. On some occasions in the mythology, the Sky Lord as identified as a male has been associated to mate with an Earth Mother, while some traditions kept the omnipotence of the Sky Lord unshared.

Europe

Ancient proto-Indo-European religion

The head deity of the Proto-Indo-European religion was the god *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr . A number of words derived from the name of this prominent deity are used in various Indo-European languages to denote a monotheistic God. Nonetheless, in spite of this, Proto-Indo-European religion itself was not monotheistic.

In Eastern Europe, the ancient traditions of the Slavic religion contained elements of monotheism. In the sixth century AD, the Byzantine chronicler Procopius recorded that the Slavs "acknowledge that one god, creator of lightning, is the only lord of all: to him do they sacrifice an ox and all sacrificial animals." The deity to whom Procopius is referring is the storm god Perún, whose name is derived from *Perkwunos, the Proto-Indo-European god of lightning. The ancient Slavs syncretized him with the Germanic god Thor and the Biblical prophet Elijah.

Ancient Greek religion

Classical Greece

The surviving fragments of the poems of the classical Greek philosopher Xenophanes of Colophon suggest that he held views very similar to those of modern monotheists. His poems harshly criticize the traditional notion of anthropomorphic gods, commenting that "...if cattle and horses and lions had hands or could paint with their hands and create works such as men do,... [they] also would depict the gods' shapes and make their bodies of such a sort as the form they themselves have." Instead, Xenophanes declares that there is "...one god, greatest among gods and humans, like mortals neither in form nor in thought." Xenophanes's theology appears to have been monist, but not truly monotheistic in the strictest sense. Although some later philosophers, such as Antisthenes, believed in doctrines similar to those expounded by Xenophanes, his ideas do not appear to have become widely popular.

Although Plato himself was a polytheist, in his writings, he often presents Socrates as speaking of "the god" in the singular form. He does, however, often speak of the gods in the plural form as well. The Euthyphro dilemma, for example, is formulated as "Is that which is holy loved by the gods because it is holy, or is it holy because it is loved by the gods?"

Hellenistic religion

The development of pure (philosophical) monotheism is a product of the Late Antiquity. During the 2nd to 3rd centuries, early Christianity was just one of several competing religious movements advocating monotheism.

"The One" (Τὸ Ἕν) is a concept that is prominent in the writings of the Neoplatonists, especially those of the philosopher Plotinus. In the writings of Plotinus, "The One" is described as an inconceivable, transcendent, all-embodying, permanent, eternal, causative entity that permeates throughout all of existence.

A number of oracles of Apollo from Didyma and Clarus, the so-called "theological oracles", dated to the 2nd and 3rd century CE, proclaim that there is only one highest god, of whom the gods of polytheistic religions are mere manifestations or servants. 4th century CE Cyprus had, besides Christianity, an apparently monotheistic cult of Dionysus.

The Hypsistarians were a religious group who believed in a most high god, according to Greek documents. Later revisions of this Hellenic religion were adjusted towards monotheism as it gained consideration among a wider populace. The worship of Zeus as the head-god signaled a trend in the direction of monotheism, with less honour paid to the fragmented powers of the lesser gods.

Western Asia

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

Judaism is traditionally considered one of the oldest monotheistic religions in the world, although in the 8th century BCE the Israelites were polytheistic, with their worship including the gods El, Baal, Asherah, and Astarte. Yahweh was originally the national god of the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah. During the 8th century BCE, the worship of Yahweh in Israel was in competition with many other cults, described by the Yahwist faction collectively as Baals. The oldest books of the Hebrew Bible reflect this competition, as in the books of Hosea and Nahum, whose authors lament the "apostasy" of the people of Israel, threatening them with the wrath of God if they do not give up their polytheistic cults.

As time progressed, the henotheistic cult of Yahweh grew increasingly militant in its opposition to the worship of other gods. Later, the reforms of King Josiah imposed a form of strict monolatrism. After the fall of Judah and the beginning of the Babylonian captivity, a small circle of priests and scribes gathered around the exiled royal court, where they first developed the concept of Yahweh as the sole God of the world.

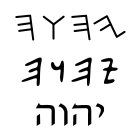

Second Temple Judaism and later Rabbinic Judaism became strictly monotheistic. The Babylonian Talmud references other, "foreign gods" as non-existent entities to whom humans mistakenly ascribe reality and power. One of the best-known statements of Rabbinic Judaism on monotheism is the Second of Maimonides' 13 Principles of faith:

God, the Cause of all, is one. This does not mean one as in one of a pair, nor one like a species (which encompasses many individuals), nor one as in an object that is made up of many elements, nor as a single simple object that is infinitely divisible. Rather, God is a unity, unlike any other possible unity.

Some in Judaism and Islam reject the Christian idea of monotheism. Modern Judaism uses the term shituf to refer to the worship of God in a manner which Judaism deems to be neither purely monotheistic (though still permissible for non-Jews) nor polytheistic (which would be prohibited).

Christianity

Among early Christians, there was considerable debate over the nature of the Godhead, with some denying the incarnation but not the deity of Jesus (Docetism) and others later calling for an Arian conception of God. Despite at least one earlier local synod rejecting the claim of Arius, this Christological issue was to be one of the items addressed at the First Council of Nicaea.

The First Council of Nicaea, held in Nicaea (in present-day Turkey), convoked by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in 325, was the first ecumenical council of bishops of the Roman Empire, and most significantly resulted in the first uniform Christian doctrine, called the Nicene Creed. With the creation of the creed, a precedent was established for subsequent general ecumenical councils of bishops (synods) to create statements of belief and canons of doctrinal orthodoxy— the intent being to define a common creed for the Church and address heretical ideas.

One purpose of the council was to resolve disagreements in Alexandria over the nature of Jesus in relationship to the Father; in particular, whether Jesus was of the same substance as God the Father or merely of similar substance. All but two bishops took the first position; while Arius' argument failed.

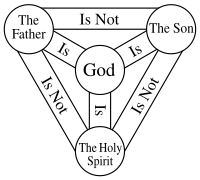

Christian orthodox traditions (Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and most Protestants) follow this decision, which was reaffirmed in 381 at the First Council of Constantinople and reached its full development through the work of the Cappadocian Fathers. They consider God to be a triune entity, called the Trinity, comprising three "persons", God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. These three are described as being "of the same substance" (ὁμοούσιος).

Christians overwhelmingly assert that monotheism is central to the Christian faith, as the Nicene Creed (and others), which gives the orthodox Christian definition of the Trinity, begins: "I believe in one God". From earlier than the times of the Nicene Creed, 325 CE, various Christian figures advocated the triune mystery-nature of God as a normative profession of faith. According to Roger E. Olson and Christopher Hall, through prayer, meditation, study and practice, the Christian community concluded "that God must exist as both a unity and trinity", codifying this in ecumenical council at the end of the 4th century.

Most modern Christians believe the Godhead is triune, meaning that the three persons of the Trinity are in one union in which each person is also wholly God. They also hold to the doctrine of a man-god Christ Jesus as God incarnate. These Christians also do not believe that one of the three divine figures is God alone and the other two are not but that all three are mysteriously God and one. Other Christian religions, including Unitarian Universalism, Jehovah's Witnesses, Mormonism and others, do not share those views on the Trinity.

Some Christian faiths, such as Mormonism, argue that the Godhead is in fact three separate individuals which include God the Father, His Son Jesus Christ, and the Holy Ghost. Each individual having a distinct purpose in the grand existence of human kind. Furthermore, Mormons believe that before the Council of Nicaea, the predominant belief among many early Christians was that the Godhead was three separate individuals. In support of this view, they cite early Christian examples of belief in subordinationism.

Unitarianism is a theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism.

Some in Judaism and some in Islam do not consider Trinitarian Christianity to be a pure form of monotheism due to the pluriform monotheistic Christian doctrine of the Trinity, classifying it as shituf in Judaism and as shirk in Islam. Trinitarian Christians, on the other hand, argue that the doctrine of the Trinity is a valid expression of monotheism, citing that the Trinity does not consist of three separate deities, but rather the three persons, who exist consubstantially (as one substance) within a single Godhead.

Islam

In Islam, God (Allāh) is all-powerful and all-knowing, the Creator, Sustainer, Ordainer and Judge of the universe. God in Islam is strictly singular (tawhid) unique (wahid) and inherently One (ahad), all-merciful and omnipotent. Allāh exists on the Al-'Arsh [Quran 7:54], but the Quran states that "No vision can encompass Him, but He encompasses all vision. For He is the Most Subtle, All-Aware." (Quran 6:103) Allāh is the only God and the same God worshiped in Christianity and Judaism(Q29:46).

Islam emerged in the 7th century CE in the context of both Christianity and Judaism, with some thematic elements similar to Gnosticism. Islamic belief states that Muhammad did not bring a new religion from God, but rather the same religion as practiced by Abraham, Moses, David, Jesus and all the other prophets of God. The assertion of Islam is that the message of God had been corrupted, distorted or lost over time, and the Quran was sent to Muhammad in order to correct the lost message of the Tawrat (Torah), Injil (Gospel) and Zabur.

The Quran asserts the existence of a single and absolute truth that transcends the world; a unique and indivisible being who is independent of the creation. The Quran rejects binary modes of thinking such as the idea of a duality of God by arguing that both good and evil generate from God's creative act. God is a universal god rather than a local, tribal or parochial one; an absolute who integrates all affirmative values and brooks no evil. Ash'ari theology, which dominated Sunni Islam from the tenth to the nineteenth century, insists on ultimate divine transcendence and holds that divine unity is not accessible to human reason. Ash'arism teaches that human knowledge regarding it is limited to what has been revealed through the prophets, and on such paradoxes as God's creation of evil, revelation had to accept bila kayfa (without [asking] how).

Tawhid constitutes the foremost article of the Muslim profession of faith, "There is no god but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God. To attribute divinity to a created entity is the only unpardonable sin mentioned in the Quran. The entirety of the Islamic teaching rests on the principle of tawhid.

Medieval Islamic philosopher Al-Ghazali offered a proof of monotheism from omnipotence, asserting there can only be one omnipotent being. For if there were two omnipotent beings, the first would either have power over the second (meaning the second is not omnipotent) or not (meaning the first is not omnipotent); thus implying that there could only be one omnipotent being.

As they traditionally profess a concept of monotheism with a singular entity as God, Judaism and Islam reject the Christian idea of monotheism. Judaism uses the term Shituf to refer to non-monotheistic ways of worshiping God. Although Muslims venerate Jesus (Isa in Arabic) as a prophet, they do not accept the doctrine that he was a begotten son of God.

Mandaeism

Mandaeism or Mandaeanism (Arabic: مندائية Mandāʼīyah), sometimes also known as Sabianism, is a monotheistic, Gnostic, and ethnic religion. Mandaeans consider Adam, Seth, Noah, Shem and John the Baptist to be prophets, with Adam being the founder of the religion and John being the greatest and final prophet. The Mandaeans believe in one God commonly named Hayyi Rabbi meaning 'The Great Life' or 'The Great Living God'. The Mandaeans speak a dialect of Eastern Aramaic known as Mandaic. The name 'Mandaean' comes from the Aramaic manda meaning "knowledge", as does Greek gnosis. The term 'Sabianism' is derived from the Sabians (Arabic: الصابئة, al-Ṣābiʾa), a mysterious religious group mentioned three times in the Quran alongside the Jews, the Christians and the Zoroastrians as a 'people of the book', and whose name was historically claimed by the Mandaeans as well as by several other religious groups in order to gain the legal protection (dhimma) offered by Islamic law. Mandaeans recognize God to be the eternal, creator of all, the one and only in domination who has no partner.

Baháʼí Faith

God in the Baháʼí Faith is taught to be the Imperishable, uncreated Being Who is the source of existence, too great for humans to fully comprehend. Human primitive understanding of God is achieved through his revelations via his divine intermediary Manifestations. In the Baháʼí faith, such Christian doctrines as the Trinity are seen as compromising the Baháʼí view that God is single and has no equal, and the very existence of the Baháʼí Faith is a challenge to the Islamic doctrine of the finality of Muhammad's revelation.

God in the Baháʼí Faith communicates to humanity through divine intermediaries, known as Manifestations of God. These Manifestations establish religion in the world. It is through these divine intermediaries that humans can approach God, and through them God brings divine revelation and law.

The Oneness of God is one of the core teachings of the Baháʼí Faith. The obligatory prayers in the Baháʼí Faith involve explicit monotheistic testimony. God is the imperishable, uncreated being who is the source of all existence. He is described as "a personal God, unknowable, inaccessible, the source of all Revelation, eternal, omniscient, omnipresent and almighty". Although transcendent and inaccessible directly, his image is reflected in his creation. The purpose of creation is for the created to have the capacity to know and love its creator. God communicates his will and purpose to humanity through intermediaries, known as Manifestations of God, who are the prophets and messengers that have founded religions from prehistoric times up to the present day.

Rastafari

Rastafari, sometimes termed Rastafarianism, is classified as both a new religious movement and social movement. It developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It lacks any centralised authority and there is much heterogeneity among practitioners, who are known as Rastafari, Rastafarians, or Rastas.

Rastafari refer to their beliefs, which are based on a specific interpretation of the Bible, as "Rastalogy". Central is a monotheistic belief in a single God—referred to as Jah—who partially resides within each individual. The former emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, is given central importance. Many Rastas regard him as an incarnation of Jah on Earth and as the Second Coming of Christ. Others regard him as a human prophet who fully recognised the inner divinity within every individual.

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism combines cosmogonic dualism and eschatological monotheism which makes it unique among the religions of the world. It is contested whether they are monotheistic, due to the presence of Ahura Mainyu, and the existence of worshipped lesser divinities such as Aharaniyita.

By some Zoroastrianism is considered a monotheistic religion, but this is contested as both true and false by both scholars, and Zoroastrians themselves. Although Zoroastrianism is often regarded as dualistic, duotheistic or bitheistic, for its belief in the hypostasis of the ultimately good Ahura Mazda (Wise Lord) and the ultimately evil Angra Mainyu (destructive spirit). Zoroastrianism was once one of the largest religions on Earth, as the official religion of the Persian Empire. By some scholars, the Zoroastrians ("Parsis" or "Zartoshtis") are sometimes credited with being some of the first monotheists and having had influence on other world religions. Gathered statistics estimates the number of adherents at between 100,000 and 200,000, with adherents living in many regions, including South Asia.

Yazidism

God in Yazidism created the world and entrusted it into the care of seven Holy Beings, known as Angels. The Yazidis believe in a divine Triad. The original, hidden God of the Yazidis is considered to be remote and inactive in relation to his creation, except to contain and bind it together within his essence. His first emanation is the Angel Melek Taûs (Tawûsê Melek), who functions as the ruler of the world and leader of the other Angels. The second hypostasis of the divine Triad is the Sheikh 'Adī ibn Musafir. The third is Sultan Ezid. These are the three hypostases of the one God. The identity of these three is sometimes blurred, with Sheikh 'Adī considered to be a manifestation of Tawûsê Melek and vice versa; the same also applies to Sultan Ezid. Yazidis are called Miletê Tawûsê Melek ("the nation of Tawûsê Melek").

God is referred to by Yazidis as Xwedê, Xwedawend, Êzdan, and Pedsha ('King'), and, less commonly, Ellah and Heq. According to some Yazidi hymns (known as Qewls), God has 1,001 names, or 3,003 names according to other Qewls.

Oceania

Aboriginal Australian religion

Aboriginal Australians are typically described as polytheistic in nature. Although some researchers shy from referring to Dreamtime figures as "gods" or "deities", they are broadly described as such for the sake of simplicity.

In Southeastern Australian cultures, the sky father Baiame is perceived as the creator of the universe (though this role is sometimes taken by other gods like Yhi or Bunjil) and at least among the Gamilaraay traditionally revered above other mythical figures. Equation between him and the Christian god is common among both missionaries and modern Christian Aboriginals.

The Yolngu had extensive contact with the Makassans and adopted religious practises inspired by those of Islam. The god Walitha'walitha is based on Allah (specifically, with the wa-Ta'ala suffix), but while this deity had a role in funerary practises it is unclear if it was "Allah-like" in terms of functions.

Andaman Islands

The religion of the Andamanese peoples has at times been described as "animistic monotheism", believing foremost in a single deity, Paluga, who created the universe. However, Paluga is not worshipped, and anthropomorphic personifications of natural phenomena are also known.

South Asia

Hinduism

As an old religion, Hinduism inherits religious concepts spanning monotheism, polytheism, panentheism, pantheism, monism, and atheism among others; and its concept of God is complex and depends upon each individual and the tradition and philosophy followed.

Hindu views are broad and range from monism, through pantheism and panentheism (alternatively called monistic theism by some scholars) to monotheism and even atheism. Hinduism cannot be said to be purely polytheistic. Hindu religious leaders have repeatedly stressed that while God's forms are many and the ways to communicate with him are many, God is one. The puja of the murti is a way to communicate with the abstract one god (Brahman) which creates, sustains and dissolves creation.

Rig Veda 1.164.46,

- Indraṃ mitraṃ varuṇamaghnimāhuratho divyaḥ sa suparṇo gharutmān,

- ekaṃ sad viprā bahudhā vadantyaghniṃ yamaṃ mātariśvānamāhuḥ

- "They call him Indra, Mitra, Varuṇa, Agni, and he is heavenly nobly-winged Garuda.

- To what is One, sages give many a title they call it Agni, Yama, Mātariśvan." (trans. Griffith)

Traditions of Gaudiya Vaishnavas, the Nimbarka Sampradaya and followers of Swaminarayan and Vallabha consider Krishna to be the source of all avatars, and the source of Vishnu himself, or to be the same as Narayana. As such, he is therefore regarded as Svayam Bhagavan.

When Krishna is recognized to be Svayam Bhagavan, it can be understood that this is the belief of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, the Vallabha Sampradaya, and the Nimbarka Sampradaya, where Krishna is accepted to be the source of all other avatars, and the source of Vishnu himself. This belief is drawn primarily "from the famous statement of the Bhagavatam" (1.3.28). A viewpoint differing from this theological concept is the concept of Krishna as an avatar of Narayana or Vishnu. It should be however noted that although it is usual to speak of Vishnu as the source of the avataras, this is only one of the names of the God of Vaishnavism, who is also known as Narayana, Vasudeva and Krishna and behind each of those names there is a divine figure with attributed supremacy in Vaishnavism.

The Rig Veda discusses monotheistic thought, as do the Atharva Veda and Yajur Veda: "Devas are always looking to the supreme abode of Vishnu" (tad viṣṇoḥ paramaṁ padaṁ sadā paśyanti sṻrayaḥ Rig Veda 1.22.20)

"The One Truth, sages know by many names" (Rig Veda 1.164.46)

"When at first the unborn sprung into being, He won His own dominion beyond which nothing higher has been in existence" (Atharva Veda 10.7.31)

"There is none to compare with Him. There is no parallel to Him, whose glory, verily, is great." (Yajur Veda 32.3)

The number of auspicious qualities of God are countless, with the following six qualities (bhaga) being the most important:

- Jñāna (omniscience), defined as the power to know about all beings simultaneously

- Aishvarya (sovereignty, derived from the word Ishvara), which consists in unchallenged rule over all

- Shakti (energy), or power, which is the capacity to make the impossible possible

- Bala (strength), which is the capacity to support everything by will and without any fatigue

- Vīrya (vigor), which indicates the power to retain immateriality as the supreme being in spite of being the material cause of mutable creations

- Tejas (splendor), which expresses His self-sufficiency and the capacity to overpower everything by His spiritual effulgence

In the Shaivite tradition, the Shri Rudram (Sanskrit श्रि रुद्रम्), to which the Chamakam (चमकम्) is added by scriptural tradition, is a Hindu stotra dedicated to Rudra (an epithet of Shiva), taken from the Yajurveda (TS 4.5, 4.7). Shri Rudram is also known as Sri Rudraprasna, Śatarudrīya, and Rudradhyaya. The text is important in Vedanta where Shiva is equated to the Universal supreme God. The hymn is an early example of enumerating the names of a deity, a tradition developed extensively in the sahasranama literature of Hinduism.

The Nyaya school of Hinduism has made several arguments regarding a monotheistic view. The Naiyanikas have given an argument that such a god can only be one. In the Nyaya Kusumanjali, this is discussed against the proposition of the Mimamsa school that let us assume there were many demigods (devas) and sages (rishis) in the beginning, who wrote the Vedas and created the world. Nyaya says that:

[If they assume such] omniscient beings, those endowed with the various superhuman faculties of assuming infinitesimal size, and so on, and capable of creating everything, then we reply that the law of parsimony bids us assume only one such, namely Him, the adorable Lord. There can be no confidence in a non-eternal and non-omniscient being, and hence it follows that according to the system which rejects God, the tradition of the Veda is simultaneously overthrown; there is no other way open.

In other words, Nyaya says that the polytheist would have to give elaborate proofs for the existence and origin of his several celestial spirits, none of which would be logical, and that it is more logical to assume one eternal, omniscient god.

Many other Hindus, however, view polytheism as far preferable to monotheism. The famous Hindu revitalist leader Ram Swarup, for example, points to the Vedas as being specifically polytheistic, and states that, "only some form of polytheism alone can do justice to this variety and richness."

Sita Ram Goel, another 20th-century Hindu historian, wrote:

I had an occasion to read the typescript of a book [Ram Swarup] had finished writing in 1973. It was a profound study of Monotheism, the central dogma of both Islam and Christianity, as well as a powerful presentation of what the monotheists denounce as Hindu Polytheism. I had never read anything like it. It was a revelation to me that Monotheism was not a religious concept but an imperialist idea. I must confess that I myself had been inclined towards Monotheism till this time. I had never thought that a multiplicity of Gods was the natural and spontaneous expression of an evolved consciousness.

Sikhism

Sikhi is a monotheistic and a revealed religion. God in Sikhi is called Akal Purakh (which means "the true immortal") or Vāhigurū the Primal being. However, other names like Ram, Allah etc. are also used to refer to the same god, who is shapeless, timeless, and sightless: niraṅkār, akaal, and alakh. Sikhi presents a unique perspective where God is present (sarav viāpak) in all of its creation and does not exist outside of its creation. God must be seen from "the inward eye", or the "heart". Sikhs follow the Aad Guru Granth Sahib and are instructed to meditate on the Naam (Name of God - Vāhigurū) to progress towards enlightenment, as its rigorous application permits the existence of communication between God and human beings.

Sikhism is a monotheistic faith that arose in northern region of the Indian subcontinent during the 16th and 17th centuries. Sikhs believe in one, timeless, omnipresent, supreme creator. The opening verse of the Guru Granth Sahib, known as the Mul Mantra, signifies this:

- Punjabi: ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਨਿਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ ॥

- Transliteration: ikk ōankār sat(i)-nām(u) karatā purakh(u) nirabha'u niravair(u) akāla mūrat(i) ajūnī saibhan(g) gur(a) prasād(i).

- One Universal creator God, The supreme Unchangeable Truth, The Creator of the Universe, Beyond Fear, Beyond Hatred, Beyond Death, Beyond Birth, Self-Existent, by Guru's Grace.

The word "ੴ" ("Ik ōaṅkār") has two components. The first is ੧, the digit "1" in Gurmukhi signifying the singularity of the creator. Together the word means: "One Universal creator God".

It is often said that the 1430 pages of the Guru Granth Sahib are all expansions on the Mul Mantra. Although the Sikhs have many names for God, some derived from Islam and Hinduism, they all refer to the same Supreme Being.

The Sikh holy scriptures refer to the One God who pervades the whole of space and is the creator of all beings in the universe. The following quotation from the Guru Granth Sahib highlights this point:

Chant, and meditate on the One God, who permeates and pervades the many beings of the whole Universe. God created it, and God spreads through it everywhere. Everywhere I look, I see God. The Perfect Lord is perfectly pervading and permeating the water, the land and the sky; there is no place without Him.

— Guru Granth Sahib, Page 782

However, there is a strong case for arguing that the Guru Granth Sahib teaches monism due to its non-dualistic tendencies:

Punjabi: ਸਹਸ ਪਦ ਬਿਮਲ ਨਨ ਏਕ ਪਦ ਗੰਧ ਬਿਨੁ ਸਹਸ ਤਵ ਗੰਧ ਇਵ ਚਲਤ ਮੋਹੀ ॥੨॥

You have thousands of Lotus Feet, and yet You do not have even one foot. You have no nose, but you have thousands of noses. This Play of Yours entrances me.

— Guru Granth Sahib, Page 13

Sikhs believe that God has been given many names, but they all refer to the One God, VāhiGurū. Sikh holy scripture (Guru Granth Sahib) speaks to all faiths and Sikhs believe that members of other religions such as Islam, Hinduism and Christianity all worship the same God, and the names Allah, Rahim, Karim, Hari, Raam and Paarbrahm are, therefore, frequently mentioned in the Sikh holy scripture (Guru Granth Sahib) . God in Sikhism is most commonly referred to as Akal Purakh (which means "the true immortal") or Waheguru, the Primal Being.