| Founding Fathers of the United States | |

|---|---|

| 1760s–1820s | |

The Committee of Five (Adams, Livingston, Sherman, Jefferson, and Franklin) present their draft of the Declaration of Independence to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia on June 28, 1776, as depicted in John Trumbull's 1819 portrait | |

| Location | The Thirteen Colonies |

| Including | Signers of the Declaration of Independence (1776), Articles of Confederation (1781), and United States Constitution (1789) |

| Leader(s) | |

| Key events |

|

The Founding Fathers of the United States, commonly referred to simply as the Founding Fathers, were a group of late 18th century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the War of Independence from Great Britain, established the United States, and crafted a framework of government for the new nation.

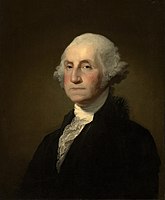

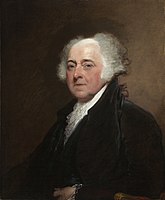

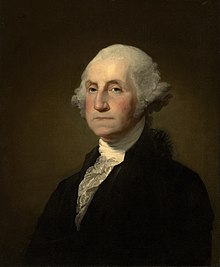

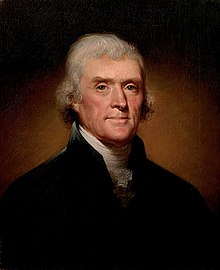

America's Founders are defined as those who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, and the United States Constitution, and others. In 1973, historian Richard B. Morris identified seven figures as key Founders, based on what he called the "triple tests" of leadership, longevity, and statesmanship: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington.

Historical founders

Historian Richard Morris' selection of seven key founders was widely accepted through the 20th century. John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin were members of the Committee of Five that were charged by the Second Continental Congress with drafting the Declaration of Independence. Franklin, Adams, and John Jay negotiated the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which established American independence and brought an end to the American Revolutionary War. The constitutions drafted by Jay and Adams for their respective states of New York (1777) and Massachusetts (1780) proved heavily influential in the language used in developing the U.S. Constitution. The Federalist Papers, which advocated the ratification of the Constitution, were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Jay. George Washington was Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army and later president of the Constitutional Convention.

Each of these men held additional important roles in the early government of the United States. Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison served as the first four presidents; Adams and Jefferson were the nation's first two vice presidents; Jay was the nation's first chief justice; Hamilton was the first Secretary of the Treasury; Jefferson and Madison were the first two Secretaries of State; and Franklin was America's most senior diplomat from the start of the Revolutionary War through its conclusion with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

The list of Founding Founders is often expanded to include the signers of the Declaration of Independence and individuals who later ratified the U.S. Constitution. Some scholars regard all delegates to the Constitutional Convention as Founding Fathers whether they approved the Constitution or not. In addition, some historians include signers of the Articles of Confederation, which was adopted in 1781 as the nation's first constitution.

Beyond this, the criterion for inclusion varies. Historians with an expanded view of the list of Founding Fathers include Revolutionary War military leaders and Revolutionary participants in developments leading up to the war, including prominent writers, orators, and other men and women who contributed to the American Revolutionary cause. Since the 19th century, Founding Fathers have shifted from the concept of the Founders as demigods who created the modern nation-state to take into account the inability of the founding generation to quickly remedy issues such as slavery, which was a global institution at the time, and the treatment of Native Americans. Other scholars of the American founding suggest that the Founding Fathers' accomplishments and shortcomings be viewed within the context of their times.

Origin of phrase

The phrase "Founding Fathers" was first coined by U.S. Senator Warren G. Harding in his keynote speech at the Republican National Convention of 1916. Harding later repeated the phrase at his March 4, 1921 inauguration. While U.S. presidents used the terms "founders" and "fathers" in their speeches throughout much of the early 20th century, it was another 60 years before Harding's phrase would be used again during the inaugural ceremonies. Ronald Reagan referred to "Founding Fathers" at both his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and his second on January 20, 1985.

In 1811, responding to praise for his generation, John Adams wrote to Josiah Quincy III, "I ought not to object to your Reverence for your Fathers as you call them ... but to tell you a very great secret ... I have no reason to believe We were better than you are." He also wrote, "Don't call me, ... Father ... [or] Founder ... These titles belong to no man, but to the American people in general."

In Thomas Jefferson's second inaugural address in 1805, he referred to those who first came to the New World as "forefathers". At his 1825 inauguration, John Quincy Adams called the U.S. Constitution "the work of our forefathers" and expressed his gratitude to "founders of the Union". In July of the following year, John Quincy Adams, in an executive order upon the deaths of his father John Adams and Jefferson, who died on the same day, paid tribute to them as both "Fathers" and "Founders of the Republic". These terms were used in the U.S. throughout the 19th century, from the inaugurations of Martin Van Buren and James Polk in 1837 and 1845, to Abraham Lincoln's Cooper Union speech in 1860 and his Gettysburg Address in 1863, and up to William McKinley's first inauguration in 1897.

At a 1902 celebration of Washington's Birthday in Brooklyn, James M. Beck, a constitutional lawyer and later a U.S. Congressman, delivered an address, "Founders of the Republic", in which he connected the concepts of founders and fathers, saying: "It is well for us to remember certain human aspects of the founders of the republic. Let me first refer to the fact that these fathers of the republic were for the most part young men."

Framers and signers

The National Archives has identified three founding documents as the "Charters of Freedom": Declaration of Independence, United States Constitution, and Bill of Rights. According to the Archives, these documents "have secured the rights of the American people for more than two and a quarter centuries and are considered instrumental to the founding and philosophy of the United States." In addition, as the nation's first constitution, the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union is also a founding document. As a result, signers of three key documents are generally considered to be Founding Fathers of the United States: Declaration of Independence (DI), Articles of Confederation (AC), and U.S. Constitution (USC). The following table provides a list of these signers, some of whom signed more than one document.

Other delegates

The 55 delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention are referred to as framers. Of these, 16 failed to sign the document. Three refused, while the remainder left early, either in protest of the proceedings or for personal reasons. Nevertheless, some sources regard all framers as Founders, including those who did not sign:

- William Richardson Davie, North Carolina

- Oliver Ellsworth, Connecticut

- Elbridge Gerry, Massachusetts *

- William Houston, New Jersey

- William Houstoun, Georgia

- John Lansing Jr., New York

- Alexander Martin, North Carolina

- Luther Martin, Maryland

- George Mason, Virginia *

- James McClurg, Virginia

- John Francis Mercer, Maryland

- William Pierce, Georgia

- Edmund Randolph, Virginia *

- Caleb Strong, Massachusetts

- George Wythe, Virginia

- Robert Yates, New York

(*) Randolph, Mason, and Gerry were the only three present at the Constitution's adoption who refused to sign.

Additional Founding Fathers

In addition to the signers and Framers of the founding documents and one of the seven notable leaders previously mentioned—John Jay—the following are regarded as Founders based on their contributions to the creation and early development of the new nation:

- Elias Boudinot, New Jersey representative in the Continental Congress, Congress of the Confederation (president 1782–1783), and the first three U.S. Congresses. Boudinot was director of the U.S. Mint under presidents Washington, Adams, and Jefferson, and also was the founding president of the American Bible Society.

- George Clinton, first governor of New York, 1777–1795, served again from 1801 to 1805, and was the fourth vice president of the US, 1805–1812. He was an anti-Federalist advocate of the Bill of Rights.

- Patrick Henry, gifted orator, known for his famous quote, "Give me liberty, or give me death!", served in the First Continental Congress in 1774 and briefly in the Second Congress in 1775 before returning to Virginia to lead its militia. He then completed terms as the first and sixth governor of Virginia, 1776–1779 and 1784–1786.

- Esek Hopkins, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Navy

- Henry Knox served as chief artillery officer in most of Washington's campaigns. His earliest achievement was the capture of over 50 pieces of artillery, primarily cannons, at New York's Fort Ticonderoga, one of the keys to Washington's capture of Boston in early 1776. Knox became the first Secretary of War under the U.S. Constitution in 1789.

- Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, French Marquis who became a Continental Army general. Served without pay, brought a ship to America, outfitted for war, provided clothing and other provisions for the patriot cause, all at his own expense.

- Robert R. Livingston, member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence, 1776; first U.S. Secretary of Foreign Affairs, 1781–1783, and first Chancellor of New York, 1777–1801. He administered the presidential oath of office at the First inauguration of George Washington and with James Monroe negotiated the Louisiana Purchase as the minister to France.

- John Marshall served with George Washington at Valley Forge and later would be the first to refer to him as "the Father of his country". Appointed the fourth chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court under John Adams, Marshall defined the authority of the court and ensured the stability of the federal government during the first three decades of the 19th century.

- James Monroe, elected to the Virginia legislature (1782); member of the Continental Congress (1783–1786); fifth president of the United States for two terms (1817–1825); Negotiated the Louisiana Purchase along with Robert Livingston.

- Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense and other influential pamphlets in the 1770s; sometimes referred to as "Father of the American Revolution". While John Adams strongly criticized Paine for failing to see the need for a separation of powers in government, Common Sense proved crucial in building support for independence following its publication in January 1776.

- Peyton Randolph, speaker of Virginia's House of Burgesses, president of the First Continental Congress, and a signer of the Continental Association.

- John Rogers, Maryland lawyer and judge, delegate to the Continental Congress who voted for the Declaration of Independence but fell ill before he could sign it.

- Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress from its formation to its final session, 1774–1789.

- Joseph Warren, respected physician and architect of the Revolutionary movement, known as the "Founding Martyr" for his death at the Battle of Bunker Hill, drafted the Suffolk Resolves in response to the Intolerable Acts.

- "Mad Anthony" Wayne, a prominent army general during the Revolutionary War.

- Thomas Willing, delegate to the Continental Congress from Pennsylvania, the first president of the Bank of North America, and the first president of the First Bank of the United States

- Henry Wisner, New York Continental Congress delegate who voted for the Declaration of Independence but left Philadelphia before the signing.

Women founders

Historians have come to recognize the roles women played in the nation's early development, using the term "Founding Mothers". Among the females honored in this respect are:

- Abigail Adams, wife, confidant, advisor to John Adams, second First Lady, and mother of the sixth U.S. president John Quincy Adams, famously extolled her husband to "Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors . . . [or] we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation".

- Mercy Otis Warren, poet, playwright, and pamphleteer during the American Revolution

Other patriots

The following men and women are also recognized for the notable contributions they made during the founding era:

- Ethan Allen, military leader and founder of Vermont.

- Richard Allen, African-American bishop, founder of the Free African Society and the African Methodist Episcopal Church

- Crispus Attucks, believed to be of Native American and African descent, was the first of five persons killed in the Boston Massacre of 1770, and thus the first to die in the American Revolution. Of the deaths at Boston John Adams would later write, "On that night the foundations of American independence was laid."

- John Barry, an officer in the Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War, has been credited as "The Father of the American Navy" (sharing the descriptor with John Paul Jones and John Adams) and was the first captain of a U.S. warship commissioned for service under the Continental flag.

- Israel Bissell, a patriot post rider in Massachusetts who rode the news to Philadelphia of the British attack on Lexington and Concord.

- Hugh Henry Brackenridge, lawyer, judge, author, chaplin in the Continental army, ally of Madison, collaborator with Freneau, and central figure in early western Pennsylvania

- Aaron Burr, vice president under Jefferson

- Cato, a Black Patriot and slave who served as a spy alongside his owner, Hercules Mulligan. Cato carried intelligence gathered by Mulligan to officers in the Continental Army and other revolutionaries, including through British-held territory, which was credited for likely saving George Washington's life on at least two occasions. He was granted his freedom in 1778 for his service.

- Angelica Schuyler Church, sister-in-law of Alexander Hamilton, corresponded with many of the leading Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and the Marquis de Lafayette.

- Tench Coxe, economist in the Continental Congress

- Silas Deane, a delegate to the Continental Congress who signed the Continental Association, became the first foreign diplomat from the U.S. to France where he helped negotiate and then signed the 1778 Treaty of Alliance that allied France with the United States during the Revolutionary War.

- Philip Freneau, called the "Poet of the Revolution"

- Albert Gallatin, politician and treasury secretary

- Nathanael Greene, Revolutionary War general; commanded the southern theater

- Nathan Hale, captured U.S. soldier, executed in 1776 for spying on British in New York

- Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, wife of Alexander Hamilton

- James Iredell, essayist for independence and advocate for the constitution, early Supreme Court Justice

- John Paul Jones, U.S. Navy captain; when the British requested his surrender, he replied, "I have not yet begun to fight"

- Benjamin Kent, lawyer, Massachusetts Attorney General, senior member of the Sons of Liberty and the North End Caucus. In April, 1776, Kent encouraged John Adams to declare American independence.

- Tadeusz Kościuszko, American general, former Polish army general

- Bernardo de Galvez, Spanish military, governor of Spanish Louisiana. Captured Baton Rouge, Natchez, and Mobile, all in British West Florida.

- John Laurance, New York politician and judge who served as Judge advocate general during the Revolution

- Arthur Lee, diplomat who helped negotiate and signed the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France, along with Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane.

- Henry Lee III, army officer and Virginia governor

- William Maclay, Pennsylvania politician and U.S. senator

- Philip Mazzei, Italian physician, merchant, and author

- Daniel Morgan, military leader and Virginia congressman

- Hercules Mulligan, Irish-American tailor and spy, member of the Sons of Liberty. Introduced Alexander Hamilton into New York society and helped him recruit men for his artillery units.

- Samuel Nicholas, commander-in-chief of the Continental Marines

- James Otis Jr., one of the earliest proponents of patriotic causes, an opponent of slavery, and leader of Massachusetts' Committee of Correspondence, all in the 1760s.

- Andrew Pickens, army general and South Carolina congressman

- Timothy Pickering, Secretary of War, U.S. secretary of state, from Massachusetts. Fired by President John Adams; replaced by John Marshall.

- Oliver Pollock, a merchant, diplomat, and financier of the American Revolutionary War

- Israel Putnam, army general

- Paul Revere, silversmith, member of the Sons of Liberty which staged the Boston Tea Party, and one of two horsemen in the midnight ride.

- Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, French army general

- Haym Salomon, along with Robert Morris, was the prime financier of the American Revolution. He also spied for the Continental Army.

- Philip Schuyler, Revolutionary War general, U.S. senator from New York, father of the Schuyler sisters.

- John Sevier, cofounder of the Watauga Association, Revolutionary War soldier, called the Founding Father of Tennessee

- Arthur St. Clair, major general, president of the Confederation Congress, and later first governor of the Northwest Territory

- Thomas Sumter, South Carolina military leader, and member of both houses of Congress

- John Trumbull, artist, whose paintings inform the collective memory of the early American Republic

- Richard Varick, private secretary to George Washington, recorder of New York City (1786); Speaker of the New York Assembly (1787); second attorney general of New York state (1788–1789); Mayor of New York City (1789–1801); founder of the American Bible Society (1828)

- Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, Prussian officer; Inspector General of Continental Army; present at Valley forge with Washington, training militia

- Noah Webster, political writer, lexicographer, educator

The colonies unite (1765–1774)

In the mid-1760s, Parliament began levying taxes on the colonies to finance Britain's debts from the French and Indian War, a decade-long conflict that ended in 1763. Opposition to Stamp Act and Townshend Acts united the colonies in a common cause. While the Stamp Act was withdrawn, taxes on tea remained under the Townshend Acts and took on a new form in 1773 with Parliament's adoption of the Tea Act. The new tea tax, along with stricter customs enforcement, was not well-received across the colonies, particularly in Massachusetts.

On December 16, 1773, 150 colonists disguised as Mohawk Indians boarded ships in Boston and dumped 342 chests of tea into the city's harbor, a protest that came to be known as the Boston Tea Party. Orchestrated by Samuel Adams and the Boston Committee of Correspondence, the protest was viewed as treasonous by British authorities. In response, Parliament passed the Coercive or Intolerable Acts, a series of punitive laws that closed Boston's port and placed the colony under direct control of the British government. These measures stirred unrest throughout the colonies, which felt Parliament had overreached its authority and was posing a threat to the self-rule that had existed in the Americas since the 1600s.

Intent on responding to the Acts, twelve of the Thirteen Colonies agreed to send delegates to meet in Philadelphia as the First Continental Congress, with Georgia declining because it needed British military support in its conflict with native tribes. The concept of an American union had been entertained long before 1774, but always embraced the idea that it would be subject to the authority of the British Empire. By 1774, however, letters published in colonial newspapers, mostly by anonymous writers, began asserting the need for a "Congress" to represent all Americans, one that would have equal status with British authority.

Continental Congress (1774–1775)

The Continental Congress was convened to deal with a series of pressing issues the colonies were facing with Britain. Its delegates were men considered to be the most intelligent and thoughtful among the colonialists. In the wake of the Intolerable Acts, at the hands of an unyielding British King and Parliament, the colonies were forced to choose between either totally submitting to arbitrary Parliamentary authority or resorting to unified armed resistance. The new Congress functioned as the directing body in declaring a great war and was sanctioned only by reason of the guidance it provided during the armed struggle. Its authority remained ill-defined, and few of its delegates realized that events would soon lead them to deciding policies that ultimately established a "new power among the nations". In the process the Congress performed many experiments in government before an adequate Constitution evolved.

First Continental Congress (1774)

The First Continental Congress convened at Philadelphia's Carpenter's Hall on September 5, 1774. The Congress, which had no legal authority to raise taxes or call on colonial militias, consisted of 56 delegates, including George Washington of Virginia; John Adams and Samuel Adams of Massachusetts; John Jay of New York; John Dickinson of Pennsylvania; and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. Peyton Randolph of Virginia was unanimously elected its first president.

The Congress came close to disbanding in its first few days over the issue of representation, with smaller colonies desiring equality with the larger ones. While Patrick Henry, from the largest colony, Virginia, disagreed, he stressed the greater importance of uniting the colonies: "The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more. I am not a Virginian, but an American!". The delegates then began with a discussion of the Suffolk Resolves, which had just been approved at a town meeting in Milton, Massachusetts. Joseph Warren, chairman of the Resolves drafting committee, had dispatched Paul Revere to deliver signed copies to the Congress in Philadelphia. The Resolves called for the ouster of British officials, a trade embargo of British goods, and the formation of a militia throughout the colonies. Despite the radical nature of the resolves, on September 17 the Congress passed them in their entirety in exchange for assurances that Massachusetts' colonists would do nothing to provoke war.

The delegates then approved a series of measures, including a Petition to the King in an appeal for peace and a Declaration and Resolves which introduced the ideas of natural law and natural rights, foreshadowing some of the principles found in the Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights. The declaration asserted the rights of colonists and outlined Parliament's abuses of power. Proposed by Richard Henry Lee, it also included a trade boycott known as the Continental Association. The Association, a crucial step toward unification, empowered committees of correspondence throughout the colonies to enforce the boycott. The Declaration and its boycott directly challenged Parliament's right to govern in the Americas, bolstering the view of King George III and his administration under Lord North that the colonies were in a state of rebellion.

Lord Dartmouth, the Secretary of State for the Colonies who had been sympathetic to the Americans, condemned the newly established Congress for what he considered its illegal formation and actions. In tandem with the Intolerable Acts, British Army commander-in-chief Lieutenant General Thomas Gage was installed as governor of Massachusetts. In January 1775, Gage's superior, Lord Dartmouth, ordered the general to arrest those responsible for the Tea Party and to seize the munitions that had been stockpiled by militia forces outside of Boston. The letter took several months to reach Gage, who acted immediately by sending out 700 army regulars. During their march to Lexington and Concord on the morning of April 19, 1775, the British troops encountered militia forces, who had been warned the night before by Paul Revere and another messenger on horseback, William Dawes. Even though it is unknown who fired the first shot, the Revolutionary War began.

Second Continental Congress (1775)

On May 10, 1775, less than three weeks after the Battles at Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress convened in the Pennsylvania State House. The gathering essentially reconstituted the First Congress with many of the same delegates in attendance. Among the new arrivals were Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, John Hancock of Massachusetts, and in June, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. Hancock was elected president two weeks into the session when Peyton Randolph was recalled to Virginia to preside over the House of Burgesses as speaker, and Jefferson was named to replace him in the Virginia delegation. After adopting the rules of debate from the previous year and reinforcing its emphasis on secrecy, the Congress turned to its foremost concern, the defense of the colonies.

The provincial assembly in Massachusetts, which had declared the colony's governorship vacant, reached out to the Congress for direction on two matters: whether the assembly could assume the powers of civil government and whether the Congress would take over the army being formed in Boston. In answer to the first question, on June 9 the colony's leaders were directed to choose a council to govern within the spirit of the colony's charter. As for the second, Congress spent several days discussing plans for guiding the forces of all thirteen colonies. Finally, on June 14 Congress approved provisioning the New England militias, agreed to send ten companies of riflemen from other colonies as reinforcements, and appointed a committee to draft rules for governing the military, thus establishing the Continental Army. The next day, Samuel and John Adams nominated Washington as commander-in-chief, a motion that was unanimously approved. Two days later, on June 17, the militias clashed with British forces at Bunker Hill, a victory for Britain but a costly one.

The Congress's actions came despite the divide between conservatives who still hoped for reconciliation with England and at the other end of the spectrum, those who favored independence. To satisfy the former, Congress adopted the Olive Branch Petition on July 5, an appeal for peace to King George III written by John Dickinson. Then, the following day, it approved the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, a resolution justifying military action. The declaration, intended for Washington to read to the troops upon his arrival in Massachusetts, was drafted by Jefferson but edited by Dickinson who thought its language too strong. When the Olive Branch Petition arrived in London in September, the king refused to look at it. By then, he had already issued a proclamation declaring the American colonies in rebellion.

Declaration of Independence (1776)

Under the auspices of the Second Continental Congress and its Committee of Five, Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence. It was presented to the Congress by the Committee on June 28, and after much debate and editing of the document, on July 2, 1776, Congress passed the Lee Resolution, which declared the United Colonies independent from Great Britain. Two days later, on July 4, the Declaration of Independence was adopted. The name "United States of America", which first appeared in the Declaration, was formally approved by the Congress on September 9, 1776.

In an effort to get this important document promptly into the public realm John Hancock, president of the Second Continental Congress, commissioned John Dunlap, editor and printer of the Pennsylvania Packet, to print 200 broadside copies of the Declaration, which came to be known as the Dunlap broadsides. Printing commenced the day after the Declaration was adopted. They were distributed throughout the 13 colonies/states with copies sent to General Washington and his troops at New York with a directive that it be read aloud. Copies were also sent to Britain and other points in Europe.

Fighting for independence

While the colonists were fighting the British to gain independence their newly formed government, with its Articles of Confederation, were put to the test, revealing the shortcomings and weaknesses of America's first Constitution. During this time Washington became convinced that a strong federal government was urgently needed, as the individual states were not meeting the organizational and supply demands of the war on their own individual accord. Key precipitating events included the Boston Tea Party in 1773, Paul Revere's Ride in 1775, and the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775. George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River was a major American victory over Hessian forces at the Battle of Trenton and greatly boosted American morale. The Battle of Saratoga and the Siege of Yorktown, which primarily ended the fighting between American and British, were also pivotal events during the war. The 1783 Treaty of Paris marked the official end of the war.

After the war, Washington was instrumental in organizing the effort to create a "national militia" made up of individual state units, and under the direction of the Federal government. He also endorsed the creation of a military academy to train artillery offices and engineers. Not wanting to leave the country disarmed and vulnerable so soon after the war, Washington favored a peacetime army of 2600 men. He also favored the creation of a navy that could repel any European intruders. He approached Henry Knox, who accompanied Washington during most of his campaigns, with the prospect of becoming the future Secretary of War.

Treaty of Paris

After Washington's final victory at the surrender at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, more than a year passed before official negotiations for peace commenced. The Treaty of Paris was drafted in November 1782, and negotiations began in April 1783. The completed treaty was signed on September 3. Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, John Jay and Henry Laurens represented the United States, while David Hartley, a member of Parliament, and Richard Oswald, a prominent and influential Scottish businessman, represented Great Britain.

Franklin, who had a long-established rapport with the French and was almost entirely responsible for securing an alliance with them a few months after the start of the war, was greeted with high honors from the French council, while the others received due accommodations but were generally considered to be amateur negotiators. Communications between Britain and France were largely effected through Franklin and Lord Shelburne who was on good terms with Franklin. Franklin, Adams and Jay understood the concerns of the French at this uncertain juncture and, using that to their advantage, in the final sessions of negotiations convinced both the French and the British that American independence was in their best interests.

Constitutional Convention

Under the Articles of Confederation, the Congress of the Confederation had no power to collect taxes, regulate commerce, pay the national debt, conduct diplomatic relations, or effectively manage the western territories. Key leaders – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and others – began fearing for the young nation's fate. As the Articles' weaknesses became more and more apparent, the idea of creating a strong central government gained support, leading to the call for a convention to amend the Articles.

The Constitutional Convention met in the Pennsylvania State House from May 14 through September 17, 1787. The 55 delegates in attendance represented a cross-section of 18th-century American leadership. The vast majority were well-educated and prosperous, and all were prominent in their respective states with over 70 percent (40 delegates) serving in the Congress when the convention was proposed.

Many delegates were late to arrive, and after eleven days' delay, a quorum was finally present on May 25 to elect Washington, the nation's most trusted figure, as convention president. Four days later, on May 29, the convention adopted a rule of secrecy, a controversial decision but a common practice that allowed delegates to speak freely.

Virginia and New Jersey plans

Immediately following the secrecy vote, Virginia governor Edmund Randolph introduced the Virginia Plan, fifteen resolutions written by Madison and his colleagues proposing a government of three branches: a single executive, a bicameral (two-house) legislature, and a judiciary. The lower house was to be elected by the people, with seats apportioned by state population. The upper house would be chosen by the lower house from delegates nominated by state legislatures. The executive, who would have veto power over legislation, would be elected by the Congress, which could overrule state laws. While the plan exceeded the convention's objective of merely amending the Articles, most delegates were willing to abandon their original mandate in favor of crafting a new form of government.

Discussions of the Virginia resolutions continued into mid-June, when William Paterson of New Jersey presented an alternative proposal. The New Jersey Plan retained most of the Articles' provisions, including a one-house legislature and equal power for the states. One of the plan's innovations was a "plural" executive branch, but its primary concession was to allow the national government to regulate trade and commerce. Meeting as a committee of the whole, the delegates discussed the two proposals beginning with the question of whether there should be a single or three-fold executive and then whether to grant the executive veto power. After agreeing on a single executive who could veto legislation, the delegates turned to an even more contentious issue, legislative representation. Larger states favored proportional representation based on population, while smaller states wanted each state to have the same number of legislators.

Connecticut Compromise

By mid-July, the debates between the large-state and small-state factions had reached an impasse. With the convention on the verge of collapse, Roger Sherman of Connecticut introduced what became known as the Connceticut (or Great) Compromise. Sherman's proposal called for a House of Representatives elected proportionally and a Senate where all states would have the same number of seats. On July 16, the compromise was approved by the narrowest of margins, 5 states to 4.

The proceedings left most delegates with reservations. Several went home early in protest, believing the convention was overstepping its authority. Others were concerned about the lack of a Bill of Rights safeguarding individual liberties. Even Madison, the Constitution's chief architect, was dissatisfied, particularly over equal representation in the Senate and the failure to grant Congress the power to veto state legislation. Misgivings aside, a final draft was approved overwhelmingly on September 17, with 11 states in favor and New York unable to vote since it had only one delegate remaining, Hamilton. Rhode Island, which was in a dispute over the state's paper currency, had refused to send anyone to the convention. Of the 42 delegates present, only three refused to sign: Randolph and George Mason, both of Virginia, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts.

State ratification conventions

The U. S. Constitution faced one more hurdle: approval by the legislatures in at least nine of the 13 states. Within three days of the signing, the draft was submitted to the Congress of the Confederation, which forwarded the document to the states for ratification. In November, Pennsylvania's legislature convened the first of the conventions. Before it could vote, Delaware became the first state to ratify, approving the Constitution on December 7 by a 30–0 margin. Pennsylvania followed suit five days later, splitting its vote 46–23. Despite unanimous votes in New Jersey and Georgia, several key states appeared to be leaning against ratification because of the omission of a Bill of Rights, particularly Virginia where the opposition was led by Mason and Patrick Henry, who had refused to participate in the convention claiming he "smelt a rat". Rather than risk everything, the Federalists relented, promising that if the Constitution was adopted, amendments would be added to secure people's rights.

Over the next year, the string of ratifications continued. Finally, on June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify, making the Constitution the law of the land. Virginia followed suit four days later, and New York did the same in late July. After North Carolina's assent in November, another year-and-a-half would pass before the 13th state would weigh in. Facing trade sanctions and the possibility of being forced out of the union, Rhode Island approved the Constitution on May 29, 1790, by a begrudging 34–32 vote.

New form of government

The Constitution officially took effect on March 4, 1789, when the House and Senate met for their first sessions. On April 30, Washington was sworn in as the nation's first president. Ten amendments, known collectively as the United States Bill of Rights, were ratified on December 15, 1791. Because the delegates were sworn to secrecy, Madison's notes on the ratification were not published until after his death in 1836.

Bill of Rights

The Constitution, as drafted, was sharply criticized by the Anti-Federalists, a group that contended the document failed to safeguard individual liberties from the federal government. Leading Anti-Federalists included Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee, both from Virginia, and Samuel Adams of Massachusetts. Delegates at the Constitutional Convention who shared their views were Virginians George Mason and Edmund Randolph and Massachusetts representative Elbridge Gerry, the three delegates who refused to sign the final document. Henry, who derived his hatred of a central governing authority from his Scottish ancestry, did all in his power to defeat the Constitution, opposing Madison every step of the way.

The criticisms are what led to the amendments proposed under the Bill of Rights. Madison, the bill's principal author, was originally opposed to the amendments, but was influenced by the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights, primarily written by Mason, and the Declaration of Independence, by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, while in France, shared Henry's and Mason's fears about a strong central government, especially the president's power, but because of his friendship with Madison and the pending Bill of Rights, he quieted his concerns. Alexander Hamilton, however, was opposed to a Bill of Rights believing the amendments not only unnecessary but dangerous:

Why declare things shall not be done, which there is no power to do ... that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed?

Madison had no way of knowing the debate between Virginia's two

legislative houses would delay the adoption of the amendments for more

than two years. The final draft, referred to the states by the federal Congress on September 25, 1789, was not ratified by Virginia's Senate until December 15, 1791.

The Bill of Rights drew its authority from the consent of the people and held that,

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

— Article 11.

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

— Article 12.

Madison came to be recognized as the founding era's foremost proponent of religious liberty, free speech, and freedom of the press.

Ascending to the presidency

The first five U.S. presidents are regarded as Founding Fathers for their active participation in the American Revolution: Washington, John Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. Each of them served as a delegate to the Continental Congress.

Demographics and other characteristics

The Founding Fathers represented the upper echelon of political leadership in the British colonies during the latter half of the 18th century. All were leaders in their communities and respective colonies who were willing to assume responsibility for public affairs.

Of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, and U.S. Constitution, nearly all were native born and of British heritage, including Scots, Irish, and Welsh. Nearly half were lawyers, while the remainder were primarily businessmen and planter-farmers. The average age of the founders was 43. Benjamin Franklin, born in 1706, was the oldest, while only a few were born after 1750 and thus were in their 20s.

The following sections discuss these and other demographic topics in greater detail. For the most part, the information is confined to signers/delegates associated with the Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, and Constitution.

Political experience

All of the Founding Fathers had extensive political experience at the national and state levels. As just one example, the signers of the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation were members of Second Continental Congress, while four-fifths of the delegates at the Constitutional Convention had served in the Congress either during or prior to the convention. The remaining fifth attending the convention were recognized as leaders in the state assemblies that appointed them.

Following are brief profiles of the political backgrounds of some of the more notable founders:

- John Adams began his political career as a town council member in Braintree outside Boston. He came to wider attention following a series of essays he wrote during the Stamp Act crisis of 1765. In 1770, he was elected to the Massachusetts General Assembly, went on to lead Boston's Committee of Correspondence, and in 1774, was elected to the Continental Congress. Two decades later, Adams would become the second president of the nation he helped found.

- John Dickinson was one of the leaders of the Pennsylvania Assembly during the 1770s. As a member of the First and Second Continental Congress, he wrote two petitions for the Congress to King George III seeking a peaceful solution. Dickinson opposed independence and refused to sign the Declaration of Independence, but served as an officer in the militia and wrote the initial draft of the Articles of Confederation. In the 1780s, he served as president of Pennsylvania and president of Delaware

- Benjamin Franklin retired from his business activities in 1747 and was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1751. He was sent to London in 1757 for the first of two diplomatic missions on behalf of the colony. Upon returning from England in 1775, Franklin was elected to the Second Continental Congress. After signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776, he was appointed Minister to France and then Sweden, and in 1783 helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris. Franklin was governor of Pennsylvania from 1785 to 1788 and was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

- John Jay was a New York delegate to the First and Second Continental Congress and in 1778 was elected Congress president. In 1782, he was summoned to Paris by Franklin to help negotiate the Treaty of Paris with Great Britain. As a supporter of the proposed Constitution, he wrote five of the Federalist Papers and became the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court following the Constitution's adoption. Minister to Spain

- Thomas Jefferson was a delegate from Virginia to the Second Continental Congress (1775–1776) and was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. He was elected the second governor of Virginia (1779–1781) and served as Minister to France (1785–1789).

- Robert Morris had been a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly and president of Pennsylvania's Committee of Safety. He was also a member of the Committee of Secret Correspondence and member of the Second Continental Congress.

- Roger Sherman had served in the First and Second Continental Congresses, Connecticut House of Representatives and Justice of the Peace.

Education

More than a third of the Founding Fathers attended or graduated from colleges in the American colonies, while additional founders attended college abroad, primarily in England and Scotland. All other founders either were home schooled, received tutoring, completed apprenticeships, or were self-educated.

American colleges

Following is a listing of founders who graduated from six of the nine colleges established in the Americas during the Colonial Era. A few founders, such as Alexander Hamilton and James Monroe, attended college but did not graduate. The other three colonial colleges, all founded in 1760s, included Brown University (originally College of Rhode Island), Dartmouth College, and Rutgers University (originally Queen's College).

- College of William & Mary: Thomas Jefferson, John Blair Jr., James McClurg, James Francis Mercer, Edmund Randolph

- Columbia University (originally King's College): John Jay, Robert R. Livingston, Gouverneur Morris,

- Harvard University (originally Harvard College): John Adams, Samuel Adams, Francis Dana, William Ellery, Elbridge Gerry, John Hancock, William Hooper, William Samuel Johnson (also Yale), Rufus King, James Lovell, Robert Treat Paine, Caleb Strong, Joseph Warren, John Wentworth Jr., William Williams

- Princeton University (originally The College of New Jersey): Gunning Bedford Jr., William Richardson Davie, Jonathan Dayton, Oliver Ellsworth, Joseph Hewes, William Houstoun, Richard Hutson, James Madison, Alexander Martin, Luther Martin, William Paterson, Joseph Reed, Benjamin Rush, Nathaniel Scudder, Jonathan Bayard Smith, Richard Stockton

- University of Pennsylvania (originally College of Philadelphia): Francis Hopkinson, Henry Marchant, Thomas Mifflin, William Paca, Hugh Williamson

- Yale University (originally Yale College): Andrew Adams, Abraham Baldwin, Lyman Hall, Titus Hosmer, Jared Ingersoll, William Samuel Johnson (also Harvard), Philip Livingston, William Livingston, Lewis Morris, Oliver Wolcott

United Kingdom colleges

Following are founders who graduated from colleges in Great Britain:

- Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court in London offering legal studies for admission to the English Bar. William Houstoun, William Paca (also University of Pennsylvania graduate)

- Middle Temple, also one of the four Inns of Court: John Banister, John Blair, John Dickinson, Thomas Heyward Jr., Thomas Lynch Jr. (also University of Cambridge graduate), John Matthews, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Peyton Randolph, John Rutledge

- University of Cambridge, England: Thomas Lynch Jr. (also Middle Temple graduate), Thomas Nelson Jr.

- University of Edinburgh, Scotland: Benjamin Rush, John Witherspoon

Ethnicity

Most of the founders were natives of the American Colonies, while just nineteen were born in other parts of the British Empire.

- England: William Richardson Davie, William Duer, Button Gwinnett, Robert Morris, Thomas Paine

- Ireland: Pierce Butler, Thomas Fitzsimons, James McHenry, William Paterson, James Smith, George Taylor, Charles Thomson, Matthew Thornton

- Scotland: Edward Telfair, James Wilson, John Witherspoon

- Wales: Francis Lewis

- West Indies: Alexander Hamilton, Daniel Roberdeau

Occupations

While the Founding Fathers were engaged in a broad range of occupations, most had careers in three professions: about half the founders were lawyers, a sixth were planters/farmers, another sixth were merchants/businessmen, and the others were spread across miscellaneous professions.

- Ten founders were physicians: Josiah Bartlett, Lyman Hall, Samuel Holten, James McClurg, James McHenry (surgeon), Benjamin Rush, Nathaniel Scudder, Matthew Thornton, Joseph Warren, and Hugh Williamson.

- John Witherspoon was the only minister, although Lyman Hall had been a preacher prior to becoming a physician.

- George Washington, a Virginia planter, was a land surveyor before becoming a colonel in the Virginia Regiment.

- Benjamin Franklin was a successful printer and publisher and an accomplished scientist and inventor, in Philadelphia. Franklin retired at age 42 to focus first on scientific pursuits and then politics and diplomacy, serving as a member of the Continental Congress, first postmaster general, minister to Great Britain, France, and Sweden, and governor of Pennsylvania.

Religion

Of the 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, 28 were Anglicans (Church of England or Episcopalian), 21 were other Protestants, and three were Catholics (Daniel Carroll and Fitzsimons; Charles Carroll was Catholic but was not a Constitution signatory). Among the Protestant delegates to the Constitutional Convention, eight were Presbyterians, seven were Congregationalists, two were Lutherans, two were Dutch Reformed, and two were Methodists.

A few prominent Founding Fathers were anti-clerical, notably Jefferson. Historian Gregg L. Frazer argues that the leading Founders (John Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, Wilson, Morris, Madison, Hamilton, and Washington) were neither Christians nor Deists, but rather supporters of a hybrid "theistic rationalism". Many Founders deliberately avoided public discussion of their faith. Historian David L. Holmes uses evidence gleaned from letters, government documents, and second-hand accounts to identify their religious beliefs.

Founders on currency and postage

Four U.S. Founders are minted on American currency—Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington; Washington and Jefferson both appear on three different denominations.

| Founding Father name | Currency image | Denomination |

|---|---|---|

| George Washington |

|

Quarter dollar (quarter) 25¢ |

|

Dollar coin $1 | |

|

One dollar $1 | |

| Thomas Jefferson |

|

Five cents (nickel) 5¢ |

|

Dollar coin $1 | |

|

Two dollars $2 | |

| Alexander Hamilton |

|

Ten dollars $10 |

| Benjamin Franklin |

|

One hundred dollars $100 |

Political and cultural impact

Political rhetoric

According to David Sehat, in modern politics:

Everyone cites the Founders. Constitutional originalists consult the Founders' papers to decide original meaning. Proponents of a living and evolving Constitution turn to the Founders as the font of ideas that have grown over time. Conservatives view the Founders as architects of a free enterprise system that built American greatness. The more liberal-leaning, following their sixties parents, claim the Founders as egalitarians, suspicious of concentrations of wealth. Independents look to the Founders to break the logjam of partisan brinksmanship. Across the political spectrum, Americans ground their views in a supposed set of ideas that emerged in the eighteenth century. But, in fact, the Founders disagreed with each other....they had vast and profound differences. They argued over federal intervention in the economy and about foreign policy. They fought bitterly over how much authority rested with the executive branch, about the relationship and prerogatives of federal and state government. The Constitution provided a nearly limitless theater of argument. The founding era was, in reality, one of the most partisan periods of American history.

Holidays

Independence Day (colloquially called the Fourth of July) is a United States national holiday celebrated yearly on July 4 to commemorate the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the founding of the nation. Washington's Birthday is also observed as a national federal holiday and is also known as Presidents' Day.

Media and theater

The Founding Fathers were portrayed in the Tony Award–winning 1969 musical 1776, which depicted the debates over and eventual adoption of the Declaration of Independence. The stage production was adapted into the 1972 film of the same name. The 1989 film A More Perfect Union, which was filmed on location in Independence Hall, depicts the events of the Constitutional Convention. The writing and passing of the founding documents are depicted in the 1997 documentary miniseries Liberty!, and the passage of the Declaration of Independence is portrayed in the second episode of the 2008 miniseries John Adams and the third episode of the 2015 miniseries Sons of Liberty. The Founders also feature in the 1986 miniseries George Washington II: The Forging of a Nation, the 2002–2003 animated television series Liberty's Kids, the 2020 miniseries Washington, and in many other films and television portrayals.

Several Founding Fathers, Hamilton, Washington, Jefferson, and Madison—were reimagined in Hamilton, a 2015 musical inspired by Ron Chernow's 2004 biography Alexander Hamilton, with music, lyrics and book by Lin-Manuel Miranda. The musical won eleven Tony Awards and a Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Sports

Several major professional sports teams in the Northeastern United States are named for themes based on the founders:

- New England Patriots (National Football League)

- New England Revolution (Major League Soccer)

- New York Liberty (Women's National Basketball Association)

- Philadelphia 76ers (National Basketball Association)

- Washington Capitals (National Hockey League)

- Washington Nationals (Major League Baseball)

Religious freedom

Religious persecution had existed for centuries around the world and it existed in colonial America. Founders such as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Patrick Henry, and George Mason first established a measure of religious freedom in Virginia in 1776 with the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which became a model for religious liberty for the nation. Prior to this, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Lutherans had for a decade petitioned against the Church of England's suppression of religious liberties.

Jefferson left the Continental Congress to return to Virginia to join the fight for religious freedom, which proved difficult since many members of the Virginia legislature belonged to the established church. While Jefferson was not completely successful, he managed to have repealed the various laws that were punitive toward those with different religious beliefs. Jefferson was the architect for separation of Church and State, which opposed the use of public funds to support any established religion and believe it was unwise to link civil rights to religious doctrine.

Freedom of religion and freedom of speech ultimately were affirmed as the nation's law in the Bill of Rights. The first enumerated right in the Bill of Rights, which was adopted in 1791, was the First Amendment, which proclaims the right to freedom of religion.

Washington was also a strong proponent of religious freedom, once assuring Virginia Baptists worried that the Constitution might not protect their religious liberties, that, "... certainly, I would never have placed my signature to it." Along with Christians, Jews also viewed Washington as a champion of freedom and sought his assurances that they would enjoy complete religious freedom. Washington responded by declaring America's revolution in religion stood as an example for the rest of the world.

Slavery

The Founding Fathers were not unified on the issue of slavery and continued to accommodate it within the new nation. Some were morally opposed to it and some attempted to end it in several of the colonies, but at the national level, slavery remained protected. In her study of Jefferson, historian Annette Gordon-Reed notes, "Others of the founders held slaves, but no other founder drafted the charter for American freedom". As well as Jefferson, Washington and many other Founding Fathers were slaveowners. Some were conflicted by the institution, seeing it as immoral and politically divisive; Washington gradually became a cautious supporter of abolitionism and freed his slaves in his will. Jay and Hamilton led the successful fight to outlaw the slave trade in New York, with efforts beginning in 1777.

Founders such as Samuel Adams and John Adams were against slavery their entire lives. Rush wrote a pamphlet in 1773 which criticized the slave trade as well as the institution of slavery. In the pamphlet, Rush argued on a scientific basis that Africans are not by nature intellectually or morally inferior, and that any apparent evidence to the contrary is only the "perverted expression" of slavery, which "is so foreign to the human mind, that the moral faculties, as well as those of the understanding are debased, and rendered torpid by it." The Continental Association contained a clause which banned any Patriot involvement in slave trading.

Franklin, though he was a key founder of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, originally owned slaves whom he later manumitted (released). While serving in the Rhode Island Assembly, in 1769 Hopkins introduced one of the earliest anti-slavery laws in the colonies. When Jefferson entered public life as a member of the House of Burgesses, he began as a social reformer by an effort to secure legislation permitting the emancipation of slaves. Jay founded the New York Manumission Society in 1785, for which Hamilton became an officer. They and other members of the Society founded the African Free School in New York City, to educate the children of free blacks and slaves. When Jay was governor of New York in 1798, he helped secure and signed into law an abolition law; fully ending forced labor as of 1827. He freed his slaves in 1798. Hamilton opposed slavery, as his experiences left him familiar with it and its effect on slaves and slaveholders, though he did negotiate slave transactions for his wife's family, the Schuylers. Evidence suggests Hamilton may have owned a house slave. After the Jay Treaty was signed, Hamilton advocated that American slaves freed by the British during the Revolutionary War be forcibly returned to their enslavers. Some Founding Fathers never owned slaves, including John Adams, Samuel Adams, and Paine. Henry Laurens, on the other hand, ran the largest slave trading house in North America. In the 1750s alone, his firm, Austin and Laurens, handled the sales of more than 8000 Africans.

Slaves and slavery are mentioned only indirectly in the 1787 Constitution. For example, Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 prescribes that "three-fifths of all other Persons" are to be counted for the apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives and direct taxes. Additionally, in Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3, slaves are referred to as "persons held in service or labor". The Founding Fathers, however, did make efforts to contain slavery. Many Northern states had adopted legislation to end or significantly reduce slavery during and after the revolution. In 1782, Virginia passed a manumission law that allowed slave owners to free their slaves by will or deed. As a result, thousands of slaves were manumitted in Virginia. In the Ordinance of 1784, Jefferson proposed to ban slavery in all the western territories, which failed to pass Congress by one vote. Partially following Jefferson's plan, Congress did ban slavery in the Northwest Ordinance, for lands north of the Ohio River. The international slave trade was banned in all states except South Carolina by 1800. Finally in 1807, President Jefferson called for and signed into law a federally enforced ban on the international slave trade throughout the U.S. and its territories. It became a federal crime to import or export a slave. However, the domestic slave trade was allowed for expansion or for diffusion of slavery into the Louisiana Territory.

Reconstruction as a "Second Founding"

According to Professors Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow:

The Founding, Reconstruction (often called "the second founding"), and the New Deal are typically heralded as the most significant turning points in the country's history, with many observers seeing each of these as political triumphs through which the United States has come to more closely realize its liberal ideals of liberty and equality.

Scholars such as Eric Foner have expanded the theme into books. Black abolitionists played a key role by stressing that freed blacks needed equal rights after slavery was abolished. Biographer David Blight states that Frederick Douglass, "played a pivotal role in America's Second Founding out of the apocalypse of the Civil War, and he very much wished to see himself as a founder and a defender of the Second American Republic." Constitutional provision for racial equality for free blacks was enacted by a Republican Congress led by Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner and Lyman Trumbull. The "second founding" comprised the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution. All citizens now had federal rights that could be enforced in federal court. In a deep reaction, after 1876 freedmen lost many of these rights and had second class citizenship in the era of lynching and Jim Crow laws. Finally in the 1950s the U.S., Supreme Court started to restore those rights. Under the leadership of Martin Luther King and James Bevel, the Civil Rights movement made the nation aware of the crisis, and under President Lyndon Johnson major civil rights legislation was passed in 1964–65, and 1968.

Scholarly analysis

Historians who wrote about the American Revolution era and the founding of the United States government now number in the thousands. Their inclusion would go well beyond the scope of this article. Some of the most prominent ones, however, are listed below. While most scholarly works maintain overall objectivity, historian Arthur H. Shaffer notes that many of the early works about the American Revolution often express a national bias, or anti-bias. Shaffer maintains that this bias lends a direct insight into the minds of the founders and their adversaries respectively. He notes that any bias is the product of a national interest and prevailing political mood, and as such cannot be dismissed as having no historic value for the modern historian. Conversely, various modern accounts of history contain anachronisms, modern day ideals and perceptions used in an effort to write about the past and as such can distort the historical account in an effort to placate a modern audience.

Early historians

Several of the earliest histories of the founding of the United States and its founders were written by Jeremy Belknap, author of his three-volume work, The history of New-Hampshire, published in 1784.

- Henry Adams, grandson of John Quincy Adams, wrote a nine-volume work, The History of the United States of America During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, which is acclaimed for its literary style, documentary evidence, and first-hand knowledge of major figures during the early Revolutionary era.

- Rufus Wilmot Griswold authored Washington and the Generals of the Revolution, a two-volume work, in 1885.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, a Harvard University history professor, edited a 27-volume work, The American Nation: A History, published in 1904–1918.

- John Marshall, a U.S. Supreme Court Justice, published a two-volume biography of Washington in 1832, three years before his death.

- David Ramsay is regarded as one of the first major historians of the American Revolutionary War.

- Mercy Otis Warren, who wrote extensively about the Revolution and post-Revolution eras, published all her works anonymously until 1790.

- Mason Locke Weems authored the first biography of Washington in 1800, which includes the famed story about a young Washington cutting down a cherry tree.

- William Wirt wrote the first biography on Patrick Henry in 1805, but was accused for excessive praise of Henry.

Modern historians

Articles and books by these and other 20th- and 21st-century historians, combined with the digitization of primary sources such as handwritten letters, continue to contribute to an encyclopedic body of knowledge about the Founding Fathers:

- Ron Chernow won the Pulitzer Prize for his 2010 biography of Washington. His 2004 bestselling book Alexander Hamilton inspired the 2015 blockbuster musical of the same name.

- Douglas Southall Freeman wrote an extensive seven volume biography on Washington. Historian and George Washington biographer John E. Ferling maintains that no other biography for Washington compares to that of Freeman's work.

- Dumas Malone is noted for his six-volume biography Jefferson and His Time, for which he received the 1975 Pulitzer Prize, and for his co-editorship of the 20-volume Dictionary of American Biography.

- Annette Gordon-Reed is an American historian and Harvard Law School professor. She is noted for changing scholarship on Jefferson regarding his alleged relationship with Sally Hemings and her children. She has studied the challenges faced by the Founding Fathers, particularly as it relates to their position and actions on slavery.

- Jack P. Greene is an American historian who specializes in colonial-era American history.

- David McCullough's Pulitzer Prize–winning 2001 book John Adams focuses on Adams, and his 2005 book, 1776 details Washington's military history in the American Revolution and other independence events carried out by America's founders.

- Peter S. Onuf and Jack N. Rakove have researched Jefferson extensively.

According to American historian Joseph Ellis, the concept of the Founding Fathers of the U.S. emerged in the 1820s as the last survivors died out. Ellis says the founders, or the fathers comprised an aggregate of semi-sacred figures whose particular accomplishments and singular achievements were decidedly less important than their sheer presence as a powerful but faceless symbol of past greatness. For the generation of national leaders coming of age in the 1820s and 1830s, such as Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun, the founders represented heroic but anonymous abstraction whose long shadow fell across all followers and whose legendary accomplishments defied comparison.

We can win no laurels in a war for independence. Earlier and worthier hands have gathered them all. Nor are there places for us ... [as] the founders of states. Our fathers have filled them. But there remains to us a great duty of defence and preservation.

Daniel Webster, 1825

Noted collections

- Adams Papers Editorial Project, an ongoing project by the Massachusetts Historical Society to organize, transcribe, and documents authored by and by the family of John Adams, his wife Abigail Adams, and their family, including John Quincy Adams

- Founders Online, a searchable database of over 184,000 documents authored by or addressed to George Washington, John Jay, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams (and family), Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison

- The Papers of Benjamin Franklin at Yale University

- The Papers of James Madison at the University of Virginia

- The Papers of Thomas Jefferson at Princeton University

- The Selected Papers of John Jay at Columbia University

- The Washington Papers at the University of Virginia