In physics, the twin paradox is a thought experiment in special relativity involving identical twins, one of whom makes a journey into space in a high-speed rocket and returns home to find that the twin who remained on Earth has aged more. This result appears puzzling because each twin sees the other twin as moving, and so, as a consequence of an incorrect and naive application of time dilation and the principle of relativity, each should paradoxically find the other to have aged less. However, this scenario can be resolved within the standard framework of special relativity: the travelling twin's trajectory involves two different inertial frames, one for the outbound journey and one for the inbound journey. Another way of looking at it is to realize the travelling twin is undergoing acceleration, which makes him a non-inertial observer. In both views there is no symmetry between the spacetime paths of the twins. Therefore, the twin paradox is not actually a paradox in the sense of a logical contradiction. There is still debate as to the resolution of the twin paradox.

Starting with Paul Langevin in 1911, there have been various explanations of this paradox. These explanations "can be grouped into those that focus on the effect of different standards of simultaneity in different frames, and those that designate the acceleration [experienced by the travelling twin] as the main reason". Max von Laue argued in 1913 that since the traveling twin must be in two separate inertial frames, one on the way out and another on the way back, this frame switch is the reason for the aging difference. Explanations put forth by Albert Einstein and Max Born invoked gravitational time dilation to explain the aging as a direct effect of acceleration. However, it has been proven that neither general relativity, nor even acceleration, are necessary to explain the effect, as the effect still applies if two astronauts pass each other at the turnaround point and synchronize their clocks at that point. Such observer can be thought of as a pair of observers, one travelling away from the starting point and another travelling toward it, passing by each other where the turnaround point would be. At this moment, the clock reading in the first observer is transferred to the second one, both maintaining constant speed, with both trip times being added at the end of their journey.

History

In his famous paper on special relativity in 1905, Albert Einstein deduced that when two clocks were brought together and synchronized, and then one was moved away and brought back, the clock which had undergone the traveling would be found to be lagging behind the clock which had stayed put. Einstein considered this to be a natural consequence of special relativity, not a paradox as some suggested, and in 1911, he restated and elaborated on this result as follows (with physicist Robert Resnick's comments following Einstein's):

Einstein: If we placed a living organism in a box ... one could arrange that the organism, after any arbitrary lengthy flight, could be returned to its original spot in a scarcely altered condition, while corresponding organisms which had remained in their original positions had already long since given way to new generations. For the moving organism, the lengthy time of the journey was a mere instant, provided the motion took place with approximately the speed of light.

Resnick: If the stationary organism is a man and the traveling one is his twin, then the traveler returns home to find his twin brother much aged compared to himself. The paradox centers on the contention that, in relativity, either twin could regard the other as the traveler, in which case each should find the other younger—a logical contradiction. This contention assumes that the twins' situations are symmetrical and interchangeable, an assumption that is not correct. Furthermore, the accessible experiments have been done and support Einstein's prediction.

In 1911, Paul Langevin gave a "striking example" by describing the story of a traveler making a trip at a Lorentz factor of γ = 100 (99.995% the speed of light). The traveler remains in a projectile for one year of his time, and then reverses direction. Upon return, the traveler will find that he has aged two years, while 200 years have passed on Earth. During the trip, both the traveler and Earth keep sending signals to each other at a constant rate, which places Langevin's story among the Doppler shift versions of the twin paradox. The relativistic effects upon the signal rates are used to account for the different aging rates. The asymmetry that occurred because only the traveler underwent acceleration is used to explain why there is any difference at all, because "any change of velocity, or any acceleration has an absolute meaning".

Max von Laue (1911, 1913) elaborated on Langevin's explanation. Using Hermann Minkowski's spacetime formalism, Laue went on to demonstrate that the world lines of the inertially moving bodies maximize the proper time elapsed between two events. He also wrote that the asymmetric aging is completely accounted for by the fact that the astronaut twin travels in two separate frames, while the Earth twin remains in one frame, and the time of acceleration can be made arbitrarily small compared with the time of inertial motion. Eventually, Lord Halsbury and others removed any acceleration by introducing the "three-brother" approach. The traveling twin transfers his clock reading to a third one, traveling in the opposite direction. Another way of avoiding acceleration effects is the use of the relativistic Doppler effect .

Neither Einstein nor Langevin considered such results to be problematic: Einstein only called it "peculiar" while Langevin presented it as a consequence of absolute acceleration. Both men argued that, from the time differential illustrated by the story of the twins, no self-contradiction could be constructed. In other words, neither Einstein nor Langevin saw the story of the twins as constituting a challenge to the self-consistency of relativistic physics.

Specific example

Consider a space ship traveling from Earth to the nearest star system: a distance d = 4 light years away, at a speed v = 0.8c (i.e., 80% of the speed of light).

To make the numbers easy, the ship is assumed to attain full speed in a negligible time upon departure (even though it would actually take about 9 months accelerating at 1 g to get up to speed). Similarly, at the end of the outgoing trip, the change in direction needed to start the return trip is assumed to occur in a negligible time. This can also be modelled by assuming that the ship is already in motion at the beginning of the experiment and that the return event is modelled by a Dirac delta distribution acceleration.

The parties will observe the situation as follows:

Earth perspective

The Earth-based mission control reasons about the journey this way: the round trip will take t = 2d/v = 10 years in Earth time (i.e. everybody on Earth will be 10 years older when the ship returns). The amount of time as measured on the ship's clocks and the aging of the travelers during their trip will be reduced by the factor , the reciprocal of the Lorentz factor (time dilation). In this case α = 0.6 and the travelers will have aged only 0.6 × 10 = 6 years when they return.

Travellers' perspective

The ship's crew members also calculate the particulars of their trip from their perspective. They know that the distant star system and the Earth are moving relative to the ship at speed v during the trip. In their rest frame the distance between the Earth and the star system is α d = 0.6 × 4 = 2.4 light years (length contraction), for both the outward and return journeys. Each half of the journey takes α d / v = 2.4 / 0.8 = 3 years, and the round trip takes twice as long (6 years). Their calculations show that they will arrive home having aged 6 years. The travelers' final calculation about their aging is in complete agreement with the calculations of those on Earth, though they experience the trip quite differently from those who stay at home.

Conclusion

| Event | Earth (years) |

Spaceship (years) |

|---|---|---|

| Departure | 0 | 0 |

| End of outgoing trip = Beginning of ingoing trip |

5 | 3 |

| Arrival | 10 | 6 |

No matter what method they use to predict the clock readings, everybody will agree about them. If twins are born on the day the ship leaves, and one goes on the journey while the other stays on Earth, they will meet again when the traveler is 6 years old and the stay-at-home twin is 10 years old.

Resolution of the paradox in special relativity

The paradoxical aspect of the twins' situation arises from the fact that at any given moment the travelling twin's clock is running slow in the earthbound twin's inertial frame, but based on the relativity principle one could equally argue that the earthbound twin's clock is running slow in the travelling twin's inertial frame. One proposed resolution is based on the fact that the earthbound twin is at rest in the same inertial frame throughout the journey, while the travelling twin is not: in the simplest version of the thought-experiment, the travelling twin switches at the midpoint of the trip from being at rest in an inertial frame which moves in one direction (away from the Earth) to being at rest in an inertial frame which moves in the opposite direction (towards the Earth). In this approach, determining which observer switches frames and which does not is crucial. Although both twins can legitimately claim that they are at rest in their own frame, only the traveling twin experiences acceleration when the spaceship engines are turned on. This acceleration, measurable with an accelerometer, makes his rest frame temporarily non-inertial. This reveals a crucial asymmetry between the twins' perspectives: although we can predict the aging difference from both perspectives, we need to use different methods to obtain correct results.

Role of acceleration

Although some solutions attribute a crucial role to the acceleration of the travelling twin at the time of the turnaround, others note that the effect also arises if one imagines two separate travellers, one outward-going and one inward-coming, who pass each other and synchronize their clocks at the point corresponding to "turnaround" of a single traveller. In this version, physical acceleration of the travelling clock plays no direct role; "the issue is how long the world-lines are, not how bent". The length referred to here is the Lorentz-invariant length or "proper time interval" of a trajectory which corresponds to the elapsed time measured by a clock following that trajectory (see Section Difference in elapsed time as a result of differences in twins' spacetime paths below). In Minkowski spacetime, the travelling twin must feel a different history of accelerations from the earthbound twin, even if this just means accelerations of the same size separated by different amounts of time, however "even this role for acceleration can be eliminated in formulations of the twin paradox in curved spacetime, where the twins can fall freely along space-time geodesics between meetings".

Relativity of simultaneity

For a moment-by-moment understanding of how the time difference between the twins unfolds, one must understand that in special relativity there is no concept of absolute present. For different inertial frames there are different sets of events that are simultaneous in that frame. This relativity of simultaneity means that switching from one inertial frame to another requires an adjustment in what slice through spacetime counts as the "present". In the spacetime diagram on the right, drawn for the reference frame of the Earth-based twin, that twin's world line coincides with the vertical axis (his position is constant in space, moving only in time). On the first leg of the trip, the second twin moves to the right (black sloped line); and on the second leg, back to the left. Blue lines show the planes of simultaneity for the traveling twin during the first leg of the journey; red lines, during the second leg. Just before turnaround, the traveling twin calculates the age of the Earth-based twin by measuring the interval along the vertical axis from the origin to the upper blue line. Just after turnaround, if he recalculates, he will measure the interval from the origin to the lower red line. In a sense, during the U-turn the plane of simultaneity jumps from blue to red and very quickly sweeps over a large segment of the world line of the Earth-based twin. When one transfers from the outgoing inertial frame to the incoming inertial frame there is a jump discontinuity in the age of the Earth-based twin (6.4 years in the example above).

A non space-time approach

As mentioned above, an "out and back" twin paradox adventure may incorporate the transfer of clock reading from an "outgoing" astronaut to an "incoming" astronaut, thus eliminating the effect of acceleration. Also, the physical acceleration of clocks does not contribute to the kinematical effects of special relativity. Rather, in special relativity, the time differential between two reunited clocks is produced purely by uniform inertial motion, as discussed in Einstein's original 1905 relativity paper, as well as in all subsequent kinematical derivations of the Lorentz transformations.

Because spacetime diagrams incorporate Einstein's clock synchronization (with its lattice of clocks methodology), there will be a requisite jump in the reading of the Earth clock time made by a "suddenly returning astronaut" who inherits a "new meaning of simultaneity" in keeping with a new clock synchronization dictated by the transfer to a different inertial frame, as explained in Spacetime Physics by John A. Wheeler.

If, instead of incorporating Einstein's clock synchronization (lattice of clocks), the astronaut (outgoing and incoming) and the Earth-based party regularly update each other on the status of their clocks by way of sending radio signals (which travel at light speed), then all parties will note an incremental buildup of asymmetry in time-keeping, beginning at the "turn around" point. Prior to the "turn around", each party regards the other party's clock to be recording time differently from his own, but the noted difference is symmetrical between the two parties. After the "turn around", the noted differences are not symmetrical, and the asymmetry grows incrementally until the two parties are reunited. Upon finally reuniting, this asymmetry can be seen in the actual difference showing on the two reunited clocks.

The equivalence of biological aging and clock time-keeping

All processes—chemical, biological, measuring apparatus functioning, human perception involving the eye and brain, the communication of force—are constrained by the speed of light. There is clock functioning at every level, dependent on light speed and the inherent delay at even the atomic level. Biological aging, therefore, is in no way different from clock time-keeping. This means that biological aging would be slowed in the same manner as a clock.

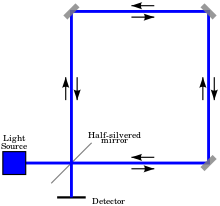

What it looks like: the relativistic Doppler shift

In view of the frame-dependence of simultaneity for events at different locations in space, some treatments prefer a more phenomenological approach, describing what the twins would observe if each sent out a series of regular radio pulses, equally spaced in time according to the emitter's clock. This is equivalent to asking, if each twin sent a video feed of themselves to each other, what do they see in their screens? Or, if each twin always carried a clock indicating his age, what time would each see in the image of their distant twin and his clock?

Shortly after departure, the traveling twin sees the stay-at-home twin with no time delay. At arrival, the image in the ship screen shows the staying twin as he was 1 year after launch, because radio emitted from Earth 1 year after launch gets to the other star 4 years afterwards and meets the ship there. During this leg of the trip, the traveling twin sees his own clock advance 3 years and the clock in the screen advance 1 year, so it seems to advance at 1⁄3 the normal rate, just 20 image seconds per ship minute. This combines the effects of time dilation due to motion (by factor ε=0.6, five years on Earth are 3 years on ship) and the effect of increasing light-time-delay (which grows from 0 to 4 years).

Of course, the observed frequency of the transmission is also 1⁄3 the frequency of the transmitter (a reduction in frequency; "red-shifted"). This is called the relativistic Doppler effect. The frequency of clock-ticks (or of wavefronts) which one sees from a source with rest frequency frest is

when the source is moving directly away. This is fobs = 1⁄3frest for v/c = 0.8.

As for the stay-at-home twin, he gets a slowed signal from the ship for 9 years, at a frequency 1⁄3 the transmitter frequency. During these 9 years, the clock of the traveling twin in the screen seems to advance 3 years, so both twins see the image of their sibling aging at a rate only 1⁄3 their own rate. Expressed in other way, they would both see the other's clock run at 1⁄3 their own clock speed. If they factor out of the calculation the fact that the light-time delay of the transmission is increasing at a rate of 0.8 seconds per second, both can work out that the other twin is aging slower, at 60% rate.

Then the ship turns back toward home. The clock of the staying twin shows "1 year after launch" in the screen of the ship, and during the 3 years of the trip back it increases up to "10 years after launch", so the clock in the screen seems to be advancing 3 times faster than usual.

When the source is moving towards the observer, the observed frequency is higher ("blue-shifted") and given by

This is fobs = 3frest for v/c = 0.8.

As for the screen on Earth, it shows that trip back beginning 9 years after launch, and the traveling clock in the screen shows that 3 years have passed on the ship. One year later, the ship is back home and the clock shows 6 years. So, during the trip back, both twins see their sibling's clock going 3 times faster than their own. Factoring out the fact that the light-time-delay is decreasing by 0.8 seconds every second, each twin calculates that the other twin is aging at 60% his own aging speed.

Left: Earth to ship. Right: Ship to Earth.

Red lines indicate low frequency images are received, blue lines indicate high frequency images are received

The x–t (space–time) diagrams at left show the paths of light signals traveling between Earth and ship (1st diagram) and between ship and Earth (2nd diagram). These signals carry the images of each twin and his age-clock to the other twin. The vertical black line is the Earth's path through spacetime and the other two sides of the triangle show the ship's path through spacetime (as in the Minkowski diagram above). As far as the sender is concerned, he transmits these at equal intervals (say, once an hour) according to his own clock; but according to the clock of the twin receiving these signals, they are not being received at equal intervals.

After the ship has reached its cruising speed of 0.8c, each twin would see 1 second pass in the received image of the other twin for every 3 seconds of his own time. That is, each would see the image of the other's clock going slow, not just slow by the ε factor 0.6, but even slower because light-time-delay is increasing 0.8 seconds per second. This is shown in the figures by red light paths. At some point, the images received by each twin change so that each would see 3 seconds pass in the image for every second of his own time. That is, the received signal has been increased in frequency by the Doppler shift. These high frequency images are shown in the figures by blue light paths.

The asymmetry in the Doppler shifted images

The asymmetry between the Earth and the space ship is manifested in this diagram by the fact that more blue-shifted (fast aging) images are received by the ship. Put another way, the space ship sees the image change from a red-shift (slower aging of the image) to a blue-shift (faster aging of the image) at the midpoint of its trip (at the turnaround, 3 years after departure); the Earth sees the image of the ship change from red-shift to blue shift after 9 years (almost at the end of the period that the ship is absent). In the next section, one will see another asymmetry in the images: the Earth twin sees the ship twin age by the same amount in the red and blue shifted images; the ship twin sees the Earth twin age by different amounts in the red and blue shifted images.

Calculation of elapsed time from the Doppler diagram

The twin on the ship sees low frequency (red) images for 3 years. During that time, he would see the Earth twin in the image grow older by 3/3 = 1 years. He then sees high frequency (blue) images during the back trip of 3 years. During that time, he would see the Earth twin in the image grow older by 3 × 3 = 9 years. When the journey is finished, the image of the Earth twin has aged by 1 + 9 = 10 years.

The Earth twin sees 9 years of slow (red) images of the ship twin, during which the ship twin ages (in the image) by 9/3 = 3 years. He then sees fast (blue) images for the remaining 1 year until the ship returns. In the fast images, the ship twin ages by 1 × 3 = 3 years. The total aging of the ship twin in the images received by Earth is 3 + 3 = 6 years, so the ship twin returns younger (6 years as opposed to 10 years on Earth).

The distinction between what they see and what they calculate

To avoid confusion, note the distinction between what each twin sees and what each would calculate. Each sees an image of his twin which he knows originated at a previous time and which he knows is Doppler shifted. He does not take the elapsed time in the image as the age of his twin now.

- If he wants to calculate when his twin was the age shown in the image (i.e. how old he himself was then), he has to determine how far away his twin was when the signal was emitted—in other words, he has to consider simultaneity for a distant event.

- If he wants to calculate how fast his twin was aging when the image was transmitted, he adjusts for the Doppler shift. For example, when he receives high frequency images (showing his twin aging rapidly) with frequency , he does not conclude that the twin was aging that rapidly when the image was generated, any more than he concludes that the siren of an ambulance is emitting the frequency he hears. He knows that the Doppler effect has increased the image frequency by the factor 1 / (1 − v/c). Therefore, he calculates that his twin was aging at the rate of

when the image was emitted. A similar calculation reveals that his twin was aging at the same reduced rate of εfrest in all low frequency images.

Simultaneity in the Doppler shift calculation

It may be difficult to see where simultaneity came into the Doppler shift calculation, and indeed the calculation is often preferred because one does not have to worry about simultaneity. As seen above, the ship twin can convert his received Doppler-shifted rate to a slower rate of the clock of the distant clock for both red and blue images. If he ignores simultaneity, he might say his twin was aging at the reduced rate throughout the journey and therefore should be younger than he is. He is now back to square one, and has to take into account the change in his notion of simultaneity at the turnaround. The rate he can calculate for the image (corrected for Doppler effect) is the rate of the Earth twin's clock at the moment it was sent, not at the moment it was received. Since he receives an unequal number of red and blue shifted images, he should realize that the red and blue shifted emissions were not emitted over equal time periods for the Earth twin, and therefore he must account for simultaneity at a distance.

Viewpoint of the traveling twin

During the turnaround, the traveling twin is in an accelerated reference frame. According to the equivalence principle, the traveling twin may analyze the turnaround phase as if the stay-at-home twin were freely falling in a gravitational field and as if the traveling twin were stationary. A 1918 paper by Einstein presents a conceptual sketch of the idea. From the viewpoint of the traveler, a calculation for each separate leg, ignoring the turnaround, leads to a result in which the Earth clocks age less than the traveler. For example, if the Earth clocks age 1 day less on each leg, the amount that the Earth clocks will lag behind amounts to 2 days. The physical description of what happens at turnaround has to produce a contrary effect of double that amount: 4 days' advancing of the Earth clocks. Then the traveler's clock will end up with a net 2-day delay on the Earth clocks, in agreement with calculations done in the frame of the stay-at-home twin.

The mechanism for the advancing of the stay-at-home twin's clock is gravitational time dilation. When an observer finds that inertially moving objects are being accelerated with respect to themselves, those objects are in a gravitational field insofar as relativity is concerned. For the traveling twin at turnaround, this gravitational field fills the universe. In a weak field approximation, clocks tick at a rate of t' = t (1 + Φ / c2) where Φ is the difference in gravitational potential. In this case, Φ = gh where g is the acceleration of the traveling observer during turnaround and h is the distance to the stay-at-home twin. The rocket is firing towards the stay-at-home twin, thereby placing that twin at a higher gravitational potential. Due to the large distance between the twins, the stay-at-home twin's clocks will appear to be sped up enough to account for the difference in proper times experienced by the twins. It is no accident that this speed-up is enough to account for the simultaneity shift described above. The general relativity solution for a static homogeneous gravitational field and the special relativity solution for finite acceleration produce identical results.

Other calculations have been done for the traveling twin (or for any observer who sometimes accelerates), which do not involve the equivalence principle, and which do not involve any gravitational fields. Such calculations are based only on the special theory, not the general theory, of relativity. One approach calculates surfaces of simultaneity by considering light pulses, in accordance with Hermann Bondi's idea of the k-calculus. A second approach calculates a straightforward but technically complicated integral to determine how the traveling twin measures the elapsed time on the stay-at-home clock. An outline of this second approach is given in a separate section below.

Difference in elapsed time as a result of differences in twins' spacetime paths

The following paragraph shows several things:

- how to employ a precise mathematical approach in calculating the differences in the elapsed time

- how to prove exactly the dependency of the elapsed time on the different paths taken through spacetime by the twins

- how to quantify the differences in elapsed time

- how to calculate proper time as a function (integral) of coordinate time

Let clock K be associated with the "stay at home twin". Let clock K' be associated with the rocket that makes the trip. At the departure event both clocks are set to 0.

- Phase 1: Rocket (with clock K') embarks with constant proper acceleration a during a time Ta as measured by clock K until it reaches some velocity V.

- Phase 2: Rocket keeps coasting at velocity V during some time Tc according to clock K.

- Phase 3: Rocket fires its engines in the opposite direction of K during a time Ta according to clock K until it is at rest with respect to clock K. The constant proper acceleration has the value −a, in other words the rocket is decelerating.

- Phase 4: Rocket keeps firing its engines in the opposite direction of K, during the same time Ta according to clock K, until K' regains the same speed V with respect to K, but now towards K (with velocity −V).

- Phase 5: Rocket keeps coasting towards K at speed V during the same time Tc according to clock K.

- Phase 6: Rocket again fires its engines in the direction of K, so it decelerates with a constant proper acceleration a during a time Ta, still according to clock K, until both clocks reunite.

Knowing that the clock K remains inertial (stationary), the total accumulated proper time Δτ of clock K' will be given by the integral function of coordinate time Δt

where v(t) is the coordinate velocity of clock K' as a function of t according to clock K, and, e.g. during phase 1, given by

This integral can be calculated for the 6 phases:

- Phase 1

- Phase 2

- Phase 3

- Phase 4

- Phase 5

- Phase 6

where a is the proper acceleration, felt by clock K' during the acceleration phase(s) and where the following relations hold between V, a and Ta:

So the traveling clock K' will show an elapsed time of

which can be expressed as

whereas the stationary clock K shows an elapsed time of

which is, for every possible value of a, Ta, Tc and V, larger than the reading of clock K':

Difference in elapsed times: how to calculate it from the ship

In the standard proper time formula

Δτ represents the time of the non-inertial (travelling) observer K' as a function of the elapsed time Δt of the inertial (stay-at-home) observer K for whom observer K' has velocity v(t) at time t.

To calculate the elapsed time Δt of the inertial observer K as a function of the elapsed time Δτ of the non-inertial observer K', where only quantities measured by K' are accessible, the following formula can be used:

where a(τ) is the proper acceleration of the non-inertial observer K' as measured by himself (for instance with an accelerometer) during the whole round-trip. The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality can be used to show that the inequality Δt > Δτ follows from the previous expression:

Using the Dirac delta function to model the infinite acceleration phase in the standard case of the traveller having constant speed v during the outbound and the inbound trip, the formula produces the known result:

In the case where the accelerated observer K' departs from K with zero initial velocity, the general equation reduces to the simpler form:

which, in the smooth version of the twin paradox where the traveller has constant proper acceleration phases, successively given by a, −a, −a, a, results in

where the convention c = 1 is used, in accordance with the above expression with acceleration phases Ta = Δt/4 and inertial (coasting) phases Tc = 0.

A rotational version

Twins Bob and Alice inhabit a space station in circular orbit around a massive body in space. Bob suits up and exits the station. While Alice remains inside the station, continuing to orbit with it as before, Bob uses a rocket propulsion system to cease orbiting and hover where he was. When the station completes an orbit and returns to Bob, he rejoins Alice. Alice is now younger than Bob. In addition to rotational acceleration, Bob must decelerate to become stationary and then accelerate again to match the orbital speed of the space station.

No twin paradox in an absolute frame of reference

Einstein's conclusion of an actual difference in registered clock times (or aging) between reunited parties caused Paul Langevin to posit an actual, albeit experimentally undetectable, absolute frame of reference:

In 1911, Langevin wrote: "A uniform translation in the aether has no experimental sense. But because of this it should not be concluded, as has sometimes happened prematurely, that the concept of aether must be abandoned, that the aether is non-existent and inaccessible to experiment. Only a uniform velocity relative to it cannot be detected, but any change of velocity .. has an absolute sense."

In 1913, Henri Poincaré's posthumous Last Essays were published and there he had restated his position: "Today some physicists want to adopt a new convention. It is not that they are constrained to do so; they consider this new convention more convenient; that is all. And those who are not of this opinion can legitimately retain the old one."

In the relativity of Poincaré and Hendrik Lorentz, which assumes an absolute (though experimentally indiscernible) frame of reference, no twin paradox arises due to the fact that clock slowing (along with length contraction and velocity) is regarded as an actuality, hence the actual time differential between the reunited clocks.

That interpretation of relativity, which John A. Wheeler calls "ether theory B (length contraction plus time contraction)", did not gain as much traction as Einstein's, which simply disregarded any deeper reality behind the symmetrical measurements across inertial frames. There is no physical test which distinguishes one interpretation from the other.

In 2005, Robert B. Laughlin (Physics Nobel Laureate, Stanford University), wrote about the nature of space: "It is ironic that Einstein's most creative work, the general theory of relativity, should boil down to conceptualizing space as a medium when his original premise [in special relativity] was that no such medium existed ... The word 'ether' has extremely negative connotations in theoretical physics because of its past association with opposition to relativity. This is unfortunate because, stripped of these connotations, it rather nicely captures the way most physicists actually think about the vacuum. ... Relativity actually says nothing about the existence or nonexistence of matter pervading the universe, only that any such matter must have relativistic symmetry (i.e., as measured)."

In Special Relativity (1968), A. P. French wrote: "Note, though, that we are appealing to the reality of A's acceleration, and to the observability of the inertial forces associated with it. Would such effects as the twin paradox exist if the framework of fixed stars and distant galaxies were not there? Most physicists would say no. Our ultimate definition of an inertial frame may indeed be that it is a frame having zero acceleration with respect to the matter of the universe at large."

![\Delta t^{2}=\left[\int _{0}^{\Delta \tau }e^{\int _{0}^{\bar {\tau }}a(\tau ')d\tau '}\,d{\bar {\tau }}\right]\,\left[\int _{0}^{\Delta \tau }e^{-\int _{0}^{\bar {\tau }}a(\tau ')d\tau '}\,d{\bar {\tau }}\right],\](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1deae869123523e92745871332b8c8117b6077b1)

![{\begin{aligned}\Delta t^{2}&=\left[\int _{0}^{\Delta \tau }e^{\int _{0}^{\bar {\tau }}a(\tau ')d\tau '}\,d{\bar {\tau }}\right]\,\left[\int _{0}^{\Delta \tau }e^{-\int _{0}^{\bar {\tau }}a(\tau ')d\tau '}\,d{\bar {\tau }}\right]\\&>\left[\int _{0}^{\Delta \tau }e^{\int _{0}^{\bar {\tau }}a(\tau ')d\tau '}\,e^{-\int _{0}^{\bar {\tau }}a(\tau ')\,d\tau '}\,d{\bar {\tau }}\right]^{2}=\left[\int _{0}^{\Delta \tau }d{\bar {\tau }}\right]^{2}=\Delta \tau ^{2}.\end{aligned}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d35d533392d395fd71134ddd34beb1ef7449dea1)