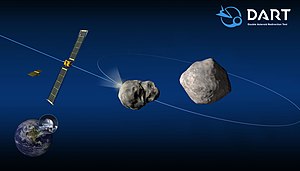

Diagram of the DART spacecraft striking Dimorphos | |

| Names | DART |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Planetary defense mission |

| Operator | NASA / APL |

| COSPAR ID | 2021-110A |

| SATCAT no. | 49497 |

| Website | |

| Mission duration | 10 months and 1 day

|

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft |

|

| Manufacturer | Applied Physics Laboratory of Johns Hopkins University |

| Launch mass |

|

| Dimensions |

|

| Power | 6.6 kW |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 24 November 2021, 06:21:02 UTC |

| Rocket | Falcon 9 Block 5, B1063.3 |

| Launch site | Vandenberg, SLC-4E |

| Contractor | SpaceX |

| Dimorphos impactor | |

| Impact date | 26 September 2022, 23:14 UTC |

| Flyby of Didymos system | |

| Spacecraft component | LICIACube (deployed from DART) |

| Closest approach | 26 September 2022, ~23:17 UTC |

| Distance | 56.7 km (35.2 mi) |

| Instruments | |

| Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation (DRACO) | |

DART mission patch | |

Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) was a NASA space mission aimed at testing a method of planetary defense against near-Earth objects (NEOs). It was designed to assess how much a spacecraft impact deflects an asteroid through its transfer of momentum when hitting the asteroid head-on. The selected target asteroid, Dimorphos, is a minor-planet moon of the asteroid Didymos; neither asteroid poses an impact threat to Earth. Launched on 24 November 2021, the DART spacecraft successfully collided with Dimorphos on 26 September 2022 at 23:14 UTC about 11 million kilometers (6.8 million miles) from Earth. The collision shortened Dimorphos' orbit by 32 minutes, greatly in excess of the pre-defined success threshold of 73 seconds. DART's success in deflecting Dimorphos was due to the momentum transfer associated with the recoil of the ejected debris, which was substantially larger than that caused by the impact itself.

DART was a joint project between NASA and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. The project was funded through NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office, managed by NASA's Planetary Missions Program Office at the Marshall Space Flight Center, and several NASA laboratories and offices provided technical support. The Italian Space Agency contributed LICIACube, a CubeSat which photographed the impact event, and other international partners, such as the European Space Agency (ESA), and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), are contributing to related or subsequent projects.

Mission history

NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) started with individual plans for missions to test asteroid deflection strategies, but by 2015, they struck a collaboration called AIDA (Asteroid Impact and Deflection Assessment) involving two separate spacecraft launches that would work in synergy. Under that proposal, the European Asteroid Impact Mission (AIM), would have launched in December 2020, and DART in July 2021. AIM would have orbited the larger asteroid to study its composition and that of its moon. DART would then kinetically impact the asteroid's moon on 26 September 2022, during a close approach to Earth.

The AIM orbiter was however canceled, then replaced by Hera which plans to start observing the asteroid four years after the DART impact. Live monitoring of the DART impact thus had to be obtained from ground-based telescopes and radar.

In June 2017, NASA approved a move from concept development to the preliminary design phase, and in August 2018 the start of the final design and assembly phase of the mission. On 11 April 2019, NASA announced that a SpaceX Falcon 9 would be used to launch DART.

Satellite impact on a small solar system body had already been implemented once, by NASA's 372 kg (820 lb) Deep Impact space probe's impactor spacecraft and for a completely different purpose (analysis of the structure and composition of a comet). On impact, Deep Impact released 19 gigajoules of energy (the equivalent of 4.8 tons of TNT), and excavated a crater up to 150 m (490 ft) wide.

Description

Spacecraft

The DART spacecraft was an impactor with a mass of 610 kg (1,340 lb) that hosted no scientific payload and had sensors only for navigation. The spacecraft cost US$330 million by the time it collided with Dimorphos in 2022.

Camera

DART's navigation sensors included a sun sensor, a star tracker called SMART Nav software (Small-body Maneuvering Autonomous Real Time Navigation), and a 20 cm (7.9 in) aperture camera called Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation (DRACO). DRACO was based on the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) onboard New Horizons spacecraft, and supported autonomous navigation to impact the asteroid's moon at its center. The optical part of DRACO was a Ritchey-Chrétien telescope with a field of view of 0.29° and a focal length of 2.6208 m (f/12.60). The spatial resolution of the images taken immediately before the impact was around 20 centimeters per pixel. The instrument had a mass of 8.66 kg (19.1 lb).

The detector used in the camera was a CMOS image sensor measuring 2,560 × 2,160 pixels. The detector records the wavelength range from 0.4 to 1 micron (visible and near infrared). A commercial off-the-shelf CMOS detector was used instead of a custom charge-coupled device in LORRI. DRACO's detector performance actually met or exceeded that of LORRI because of the improvements in sensor technology in the decade separating the design of LORRI and DRACO. Fed into an onboard computer with software descended from anti-missile technology, the DRACO images helped DART autonomously guide itself to its crash.

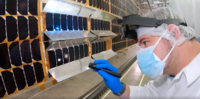

Solar arrays

Using ROSA as the structure, a small portion of the DART solar array was configured to demonstrate Transformational Solar Array technology, which has very-high-efficiency SolAero Inverted Metamorphic (IMM) solar cells and reflective concentrators providing three times more power than current other solar array technology.

Antenna

The DART spacecraft was the first spacecraft to use a new type of high-gain communication antenna, a Spiral Radial Line Slot Array (RLSA). The circularly-polarized antenna operated at the X-band NASA Deep Space Network (NASA DSN) frequencies of 7.2 and 8.4 GHz, and had a gain of 29.8 dBi on downlink and 23.6 dBi on uplink. The fabricated antenna in a flat and compact shape exceeded the given requirements and was tested through environments resulting in a TRL-6 design.

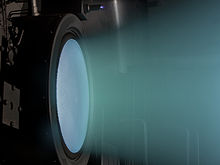

Ion thruster

DART demonstrated the NEXT gridded ion thruster, a type of solar electric propulsion. It was powered by 22 m2 (240 sq ft) solar arrays to generate the ~3.5 kW needed to power the NASA Evolutionary Xenon Thruster–Commercial (NEXT-C) engine. Early tests of the ion thruster revealed a reset mode that induced higher current (100 A) in the spacecraft structure than expected (25 A). It was decided not to use the ion thruster further as the mission could be accomplished without it, using conventional thrusters fueled by the 110 pounds of hydrazine onboard. However, the ion thrusters remained available if needed to deal with contingencies, and had DART missed its target, the ion system could have returned DART to Dimorphos two years later.

Secondary spacecraft

The Italian Space Agency (ASI) contributed a secondary spacecraft called LICIACube (Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids), a small CubeSat that piggybacked with DART and separated on 11 September 2022, 15 days before impact. It acquired images of the impact and ejecta as it drifted past the asteroid. LICIACube communicated directly with Earth, sending back images of the ejecta after the Dimorphos flyby. LICIACube is equipped with two optical cameras, dubbed LUKE and LEIA.

Effect of the impact on Dimorphos and Didymos

The spacecraft hit Dimorphos in the direction opposite to the asteroid's motion. Following the impact, the instantaneous orbital speed of Dimorphos therefore dropped slightly, which reduced the radius of its orbit around Didymos. The trajectory of Didymos was also modified, but in inverse proportion to the ratio of its mass to the much lower mass of Dimorphos. The actual velocity change and orbital shift depended on the topography and composition of the surface, among other things. The contribution of the recoil momentum from the impact ejecta produces a poorly predictable "momentum enhancement" effect. Before the impact, the momentum transferred by DART to the largest remaining fragment of the asteroid was estimated as up to 3–5 times the incident momentum, depending on how much and how fast material would be ejected from the impact crater. Obtaining accurate measurements of that effect was one of the mission's main goals and will help refine models of future impacts on asteroids.

The DART impact excavated surface/subsurface materials of Dimorphos, leading to the formation of a crater and/or some magnitude of reshaping (i.e., shape change without significant mass loss). Some of the ejecta may eventually hit Didymos's surface. If the kinetic energy delivered to its surface was high enough, reshaping may have also occur in Didymos, given its near-rotational-breakup spin rate. Reshaping on either body would have modified their mutual gravitational field, leading to a reshaping-induced orbital period change, in addition to the impact-induced orbital period change. If left unaccounted for, this could later have led to an erroneous interpretation of the effect of the kinetic deflection technique.

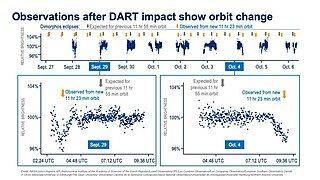

Observations of the impact

DART's companion LICIACube, the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes, and the Earth-based ATLAS observatory all detected the ejecta plume from the DART impact. On September 26, SOAR observed the visible impact trail to be over 10,000 km long. Initial estimates of the change in binary orbit period were expected within a week and with the data released by LICIACube. DART's mission science depends on careful Earth-based monitoring of the orbit of Dimorphos over the subsequent days and months. Dimorphos was too small and too close to Didymos for almost any observer to see directly, but its orbital geometry is such that it transits Didymos once each orbit and then passes behind it half an orbit later. Any observer that can detect the Didymos system therefore sees the system dim and brighten again as the two bodies cross. The impact was planned for a moment when the distance between Didymos and Earth is at a minimum, permitting many telescopes to make observations from many locations. The asteroid will be near opposition and visible high in the night sky into 2023. The change in Dimorphos's orbit around Didymos was detected by optical telescopes watching mutual eclipses of the two bodies through photometry on the Dimorphos-Didymos pair. In addition to radar observations, they confirmed that the impact shortened Dimorphos' orbital period by 32 minutes. Based on the shortened binary orbital period, the instantaneous reduction in Dimorphos' velocity component along its orbital track was determined, which indicated that substantially more momentum was transferred to Dimorphos from the escaping impact ejecta than from the impact itself. In this way, the DART kinetic impact was highly effective in deflecting Dimorphos.

Follow-up mission

In a collaborating project, the European Space Agency is developing Hera, a spacecraft that will be launched to Didymos in 2024 and arrive in 2026. (5 years after DART's impact), to do a detailed reconnaissance and assessment. Hera would carry two CubeSats, Milani and Juventas.

AIDA mission architecture

| Host spacecraft | Secondary spacecraft | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| DART | LICIACube |

|

| Hera | Juventas | |

| Milani |

| |

| SCI |

|

Mission profile

Target asteroid

The mission's target was Dimorphos in 65803 Didymos system, a binary asteroid system in which one asteroid is orbited by a smaller one. The primary asteroid (Didymos A) is about 780 m (2,560 ft) in diameter; the asteroid moon Dimorphos (Didymos B) is about 160 m (520 ft) in diameter in an orbit about 1 km (0.62 mi) from the primary. The mass of the Didymos system is estimated at 528 billion kg, with Dimorphos comprising 4.8 billion kg of that total. Choosing a binary asteroid system is advantageous because changes to Dimorphos's velocity can be measured by observing when Dimorphos subsequently passes in front of its companion, causing a dip in light that can be seen by Earth telescopes. Dimorphos was also chosen due to its appropriate size; it is in the size range of asteroids that one would want to deflect, were they on a collision course with Earth. In addition, the binary system was relatively close to the Earth in 2022, at about 11 million km (7 million mi). The Didymos system is not an Earth-crossing asteroid, and there is no possibility that the deflection experiment could create an impact hazard. On 4 October 2022, Didymos made an Earth approach of 10.6 million km (6.6 million mi).

Preflight preparations

Launch preparations for DART began on 20 October 2021, as the spacecraft began fueling at Vandenberg Space Force Base (VSFB) in California. The spacecraft arrived at Vandenberg in early October 2021 after a cross-country drive. DART team members prepared the spacecraft for flight, testing the spacecraft's mechanisms and electrical system, wrapping the final parts in multilayer insulation blankets and practicing the launch sequence from both the launch site and the mission operations center at APL. DART headed to the SpaceX Payload Processing Facility on VSFB on 26 October 2021. Two days later, the team received the green light to fill DART's fuel tank with roughly 50 kg (110 lb) of hydrazine propellant for spacecraft maneuvers and attitude control. DART also carried about 60 kg (130 lb) of xenon for the NEXT-C ion engine. Engineers loaded the xenon before the spacecraft left APL in early October 2021.

Starting on 10 November 2021, engineers mated the spacecraft to the adapter that stacks on top of the SpaceX Falcon 9 launch vehicle. The Falcon 9 rocket without the payload fairing rolled for a static fire and later came back to the processing facility again where technicians with SpaceX installed the two halves of the fairing around the spacecraft over the course of two days, 16 and 17 November, inside the SpaceX Payload Processing Facility at Vandenberg Space Force Base and the ground teams completed a successful Flight Readiness Review later that week with the fairing then attached to the rocket.

A day before launch, the launch vehicle rolled out of the hangar and onto the launch pad at Vandenberg Space Launch Complex 4 (SLC-4E); from there, it lifted off to begin DART's journey to the Didymos system and it propelled the spacecraft into space.

Launch

The DART spacecraft was launched on 24 November 2021, at 06:21:02 UTC.

Early planning suggested that DART was to be deployed into a high-altitude, high-eccentricity Earth orbit designed to avoid the Moon. In such a scenario, DART would use its low-thrust, high-efficiency NEXT ion engine to slowly escape from its high Earth orbit to a slightly inclined near-Earth solar orbit, from which it would maneuver onto a collision trajectory with its target. But because DART was launched as a dedicated Falcon 9 mission, the payload along with Falcon 9's second stage was placed directly on an Earth escape trajectory and into heliocentric orbit when the second stage reignited for a second engine startup or escape burn. Thus, although DART carries a first-of-its-kind electric thruster and plenty of xenon fuel, Falcon 9 did almost all of the work, leaving the spacecraft to perform only a few trajectory-correction burns with simple chemical thrusters as it homed in on Didymos's moon Dimorphos.

Transit

DART · 65803 Didymos · Earth · Sun · 2001 CB21 · 3361 Orpheus

The transit phase before impact lasted about 9 months. During its interplanetary travel, the DART spacecraft made a distant flyby of the 578-meter-diameter near-Earth asteroid (138971) 2001 CB21 in March 2022. DART passed 0.117 AU (17.5 million km; 10.9 million mi) from 2001 CB21 in its closest approach on 2 March 2022.

DART's DRACO camera opened its aperture door and took its first light image of some stars on 7 December 2021, when it was 3 million km (2 million mi) away from Earth. The stars in DRACO's first light image were used as calibration for the camera's pointing before it could be used to image other targets. On 10 December 2021, DRACO imaged the open cluster Messier 38 for further optical and photometric calibration.

On 27 May 2022, DART observed the bright star Vega with DRACO to test the camera's optics with scattered light. On 1 July and 2 August 2022, DART's DRACO imager observed Jupiter and its moon Europa emerging from behind the planet, as a performance test for the SMART Nav tracking system to prepare for the Dimorphos impact.

Course of the impact

DART · Didymos · Dimorphos

Two months before the impact, on 27 July 2022, the DRACO camera detected the Didymos system from approximately 32 million km (20 million mi) away and started refining its trajectory. The LICIACube nanosatellite was released on 11 September 2022, 15 days before the impact. Four hours before impact, some 90,000 km (56,000 mi) away, DART began to operate in complete autonomy under control of its SMART Nav guidance system. Three hours before impact, DART performed an inventory of objects near the target. Ninety minutes before the collision, when DART was 38,000 km (24,000 mi) away from Dimorphos, the final trajectory was established. When DART was 24,000 km (15,000 mi) away Dimorphos became discernible (1.4 pixels) through the DRACO camera which then continued to capture images of the asteroid's surface and transmit them in real-time.

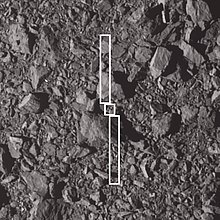

DRACO was the only instrument able to provide a detailed view of Dimorphos' surface. The use of DART's thrusters caused vibrations throughout the spacecraft and solar panels, resulting in blurred images. To ensure sharp images, the last trajectory correction was executed 4 minutes before impact and the thrusters were deactivated afterwards.

The last full image, transmitted two seconds before impact, has a spatial resolution of about 3 centimeters per pixel. The impact took place on 26 September 2022, at 23:14 UTC.

The head-on impact of the 500 kg (1,100 lb) DART spacecraft at 6.6 km/s (4.1 mi/s) likely imparted an energy of about 11 gigajoules, the equivalent of about three tonnes of TNT, and was expected to reduce the orbital velocity of Dimorphos between 1.75 cm/s and 2.54 cm/s, depending on numerous factors such as material porosity. The reduction in Dimorphos's orbital velocity brings it closer to Didymos, resulting in the moon experiencing greater gravitational acceleration and thus a shorter orbital period. The orbital period reduction from the head-on impact serves to facilitate ground-based observations of Dimorphos. An impact to the asteroid's trailing side would instead increase its orbital period towards 12 hours and make it coincide with Earth's day and night cycle, which would limit any single ground-based telescope from observing all orbital phases of Dimorphos nightly.

The measured momentum enhancement factor (called beta) of DART's impact of Dimorphos was 3.6, which means that the impact transferred roughly 3.6 times greater momentum than if the asteroid had simply absorbed the spacecraft and produced no ejecta at all – indicating the ejecta contributed more to moving the asteroid than the spacecraft did. This means one could use either a smaller impactor or shorter lead times for the same deflection. The value of beta depends on various factors, composition, density, porosity, etc. The goal is to use these results and modeling to infer what beta could be for another asteroid by observing its surface and possibly measuring its bulk density. Scientists estimate that DART’s impact displaced over 1,000,000 kg (2,200,000 lb) of dusty ejecta into space – enough to fill six or seven rail cars. The tail of ejecta from Dimorphos created by the DART impact is at least 30,000 km (19,000 mi) long with a mass of at least 1,000 t (980 long tons; 1,100 short tons), and possibly up to 10 times that much.

The DART impact on the center of Dimorphos decreased the orbital period, previously 11.92 hours, by 33±1 minutes. This large change indicates the recoil from material excavated from the asteroid and ejected into space by the impact (known as ejecta) contributed significant momentum change to the asteroid, beyond that of the DART spacecraft itself. Researchers found the impact caused an instantaneous slowing in Dimorphos' speed along its orbit of about 2.7 millimeters per second — again indicating the recoil from ejecta played a major role in amplifying the momentum change directly imparted to the asteroid by the spacecraft. That momentum change was amplified by a factor of 2.2 to 4.9 (depending on the mass of Dimorphos), indicating the momentum change transferred because of ejecta production significantly exceeded the momentum change from the DART spacecraft alone. While the orbital change was small, the change is in the velocity and over the course of years will accumulate to a large change in position. For a hypothetical Earth-threatening body, even such a tiny change could be sufficient to mitigate or prevent an impact, if applied early enough. As the diameter of Earth is around 13,000 kilometers, a hypothetical asteroid impact could be avoided with as little of a shift as half of that (6,500 kilometers). A 2 cm/s velocity change accumulates to that distance in approximately 10 years.

By smashing into the asteroid DART made Dimorphos an active asteroid. Scientists had proposed that some active asteroids are the result of impact events, but no one had ever observed the activation of an asteroid. The DART mission activated Dimorphos under precisely known and carefully observed impact conditions, enabling the detailed study of the formation of an active asteroid for the first time. Observations show that Dimorphos lost approximately 1 million kilograms of mass as a result of the collision.

Sequence of operations for impact

Gallery

-

Size of DART and the two Didymos asteroids

-

This chart offers insight into data the DART team used to determine the orbit of Dimorphos after impact.

-

Aftermath of DART Collision with Dimorphos captured by SOAR Telescope