| Vascular surgery | |

|---|---|

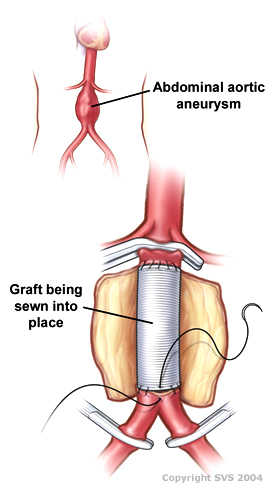

Open infrarenal aortic repair model | |

| ICD-9-CM | 38-39 |

| MeSH | D014656 |

| OPS-301 code | 5-38...5-39 |

Vascular surgery is a surgical subspecialty in which vascular diseases involving the arteries, veins, or lymphatic vessels, are managed by medical therapy, minimally-invasive catheter procedures and surgical reconstruction. The specialty evolved from general and cardiovascular surgery where it refined the management of just the vessels, no longer treating the heart or other organs. Modern vascular surgery includes open surgery techniques, endovascular (minimally invasive) techniques and medical management of vascular diseases - unlike the parent specialities. The vascular surgeon is trained in the diagnosis and management of diseases affecting all parts of the vascular system excluding the coronaries and intracranial vasculature. Vascular surgeons also are called to assist other physicians to carry out surgery near vessels, or to salvage vascular injuries that include hemorrhage control, dissection, occlusion or simply for safe exposure of vascular structures.

History

Early leaders of the field included Russian surgeon Nikolai Korotkov, noted for developing early surgical techniques, American interventional radiologist Charles Theodore Dotter who is credited with inventing minimally invasive angioplasty (1964), and Australian Robert Paton, who helped the field achieve recognition as a specialty. Edwin Wylie of San Francisco was one of the early American pioneers who developed and fostered advanced training in vascular surgery and pushed for its recognition as a specialty in the United States in the 1970s. The most notable historic figure in vascular surgery is the 1912 Nobel Prize winning surgeon, Alexis Carrel for his techniques used to suture vessels.

Evolution

The specialty continues to be based on operative arterial and venous surgery but since the early 1990s has evolved greatly. There is now considerable emphasis on minimally invasive alternatives to surgery. The field was originally pioneered by interventional radiologists like Dr. Charles Dotter, who invented angioplasty using serial dilatation of vessels.

The surgeon Dr. Thomas J. Fogarty invented a balloon catheter, designed to remove clots from occluded vessels, which was used as the eventual model to do endovascular angioplasty. Further development of the field has occurred via joint efforts between interventional radiology, vascular surgery, and interventional cardiology. This area of vascular surgery is called Endovascular Surgery or Interventional Vascular Radiology, a term that some in the specialty append to their primary qualification as Vascular Surgeon. Endovascular and endovenous procedures (e.g., EVAR) can now form the bulk of a vascular surgeon's practice.

The treatment of the aorta, the body's largest artery, dates back to Greek surgeon Antyllus, who first performed surgeries for various aneurysms in the second century AD. Modern treatment of aortic diseases stems from development and advancements from Michael DeBakey and Denton Cooley. In 1955, DeBakey and Cooley performed the first replacement of a thoracic aneurysm with a homograft. In 1958, they began using the Dacron graft, resulting in a revolution for surgeons in the repair of aortic aneurysms. He also was first to perform cardiopulmonary bypass to repair the ascending aorta, using antegrade perfusion of the brachiocephalic artery.

Dr. Ted Diethrich, one of Dr. DeBakey's associates, went on to pioneer many of the minimally invasive techniques that later became hallmarks of endovascular surgery. Dietrich later founded the Arizona Heart Hospital in 1998 and served as its medical director from 1998 to 2010. In 2000, Diethrich performed the first endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Dietrich trained several future leaders in the field of endovascular surgery at the Arizona Heart Hospital including Venkatesh Ramaiah, MD who served as medical director of the institution following Dietrich's death in 2017.

The development of endovascular surgery has been accompanied by a gradual separation of vascular surgery from its origin in general surgery. Most vascular surgeons would now confine their practice to vascular surgery and, similarly, general surgeons would not be trained or practise the larger vascular surgery operations or most endovascular procedures. More recently, professional vascular surgery societies and their training program have formally separated vascular surgery into a separate specialty with its own training program, meetings and accreditation. Notable societies are Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS), USA; Australia and New Zealand Society of Vascular Surgeons (ANZSVS). Local societies also exist (e.g., New South Wales Vascular and Melbourne Vascular Surgical Association (MVSA)). Larger societies of surgery actively separate and encourage specialty surgical societies under their umbrella (e.g., Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS)).

Currently

Arterial and venous disease treatment by angiography, stenting, and non-operative varicose vein treatment sclerotherapy, endovenous laser treatment have largely replaced major surgery in many first world countries. These procedures provide reasonable outcomes that are comparable to surgery with the advantage of short hospital stay (day or overnight for most cases) with lower morbidity and mortality rates. Historically performed by interventional radiologists, vascular surgeons have become increasingly proficient with endovascular methods. The durability of endovascular arterial procedures is generally good, especially when viewed in the context of their common clinical usage i.e. arterial disease occurring in elderly patients and usually associated with concurrent significant patient comorbidities especially ischemic heart disease. The cost savings from shorter hospital stays and less morbidity are considerable but are somewhat balanced by the high cost of imaging equipment, construction and staffing of dedicated procedural suites, and of the implant devices themselves. The benefits for younger patients and in venous disease are less persuasive but there are strong trends towards nonoperative treatment options driven by patient preference, health insurance company costs, trial demonstrating comparable efficacy at least in the medium term.

A recent trend in the United States is the stand-alone day angiography facility associated with a private vascular surgery clinic, thus allowing treatment of most arterial endovascular cases conveniently and possibly with lesser overall community cost. Similar non-hospital treatment facilities for non-operative vein treatment have existed for some years and are now widespread in many countries.

NHS England conducted a review of all 70 vascular surgery sites across England in 2018 as part of its Getting It Right First Time programme. The review specified that vascular hubs should perform at least 60 abdominal aortic aneurysm procedures and 40 carotid endarterectomies a year. 12 trusts missed both targets and many more missed one of them. A programme of concentrating vascular surgery in fewer centres is proceeding.

Vascular surgery encompasses surgery of the aorta, carotid arteries, and lower extremities, including the iliac, femoral, vascular trauma and tibial arteries. Vascular surgery also involves surgery of veins, for conditions such as May–Thurner syndrome and for varicose veins. In some regions, vascular surgery also includes dialysis access surgery and transplant surgery.

Management of arterial diseases

The management of arterial pathology excluding coronary and intracranial disease is within the scope of vascular surgeons. Disease states generally arise from narrowing of the arterial system known as stenosis or abnormal dilation referred to as an aneurysm. There are multiple mechanisms by which the arterial lumen can narrow, the most common of which is atherosclerosis. Symptomatic stenosis may also result from a complication of arterial dissection. Other less common causes of stenosis include fibromuscular dysplasia, radiation induced fibrosis or cystic adventitial disease. Dilation of an artery which retains histologic layers is called an aneurysm. An aneurysms can be fusiform (concentric dilation), saccular (outpouching) or a combination of the two. Arterial dilation which does not contain three histologic layers is considered a pseudoaneurysm. Additionally, there are a number of congenital vascular anomalies which lead to symptomatic disease that are managed by the vascular surgeon, a few of which include aberrant subclavian artery, popliteal artery entrapment syndrome or persistent sciatic artery. Vascular surgeons treat arterial diseases with a range of therapies including lifestyle modification, medications, endovascular therapy and surgery.

Aneurysms

Aortic aneurysms

- Abdominal

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) refers to aneurysmal dilation of the aorta confined to the abdominal cavity. Most commonly, aneurysms are asymptomatic and located in the infrarenal position. Often, they are discovered incidentally or on screening exams in patients with risk factors such as a history of smoking. Patients with aneurysms which have a diameter less than 5 cm are at <1% rupture risk per year. When the aneurysm meets size criteria it can be treated with aortic replacement or EVAR.

- Thoracic

Thoracic aortic aneurysms are contained in the chest. Aneurysms of the descending aorta can often be treated with thoracic endovascular aortic repair or TEVAR. Treating aneurysms which involve the ascending aorta are generally within the scope of cardiac surgeons, but upcoming endovascular technology may allow for a more minimally invasive approach in some patients.

- Thoracoabdominal

Thoroacoabdominal aneurysms are those which span the chest and abdominal cavities. The Crawford classification was developed and describes five types of thoracoabdominal aneurysms.

-

Abdominal aortic aneurysms can be classified as infrarenal, juxtarenal, pararenal or suprarenal as depicted in the illustration.

-

The Crawford Classification (Extent I-IV) and the Safi modification (Extent V) for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms is pictured above.

Other arterial aneurysms

In addition to treating aneurysms which arise from the aorta, vascular surgeons also treat aneurysms elsewhere in the body.

- Visceral artery

Visceral artery aneurysms include those isolated to the renal artery, splenic artery, celiac artery, and hepatic artery. Of these, data shows that splenic artery aneurysms are the most common.

Indications for repair differ slightly between arteries. For instance, current guidelines recommend repair of renal and splenic artery aneurysms greater than 3 cm, and those of any size in women of childbearing age; whereas celiac and hepatic artery aneurysms are indicated for repair when their size is greater than 2 cm. This is in contrast to superior mesenteric artery aneurysms which should be repaired regardless of size when they are discovered.

- Popliteal artery

A popliteal artery aneurysm is an arterial aneurysm localized in the popliteal artery which courses behind the knee. Unlike aneurysms located in the abdomen, popliteal artery aneurysm rarely present with rupture but rather with symptoms of acute limb ischemia due to embolization of thrombus. Thus, when a patient presents with an asymptomatic popliteal aneurysm that is greater than 2 cm in diameter a vascular surgeon are able to offer vascular bypass or endovascular exclusion depending on several factors.

Arterial dissections

The artery wall is composed of three concentric layers: the intima, media and adventitia. In general, an arterial dissection is a tear in the innermost layer of the arterial wall that makes a separation which allows blood to flow, and collect, between the layers. Arterial dissections include: an aortic dissection (aorta), a coronary artery dissection (coronary artery), two types of cervical artery dissection involving one of the arteries in the neck – a carotid artery dissection (carotid artery), and a vertebral artery dissection (vertebral artery), a pulmonary artery dissection is an extremely rare condition as a complication of chronic pulmonary hypertension.

Whereas cardiac surgeons are usually in charge of managing type A dissections, type B dissections are typically managed by vascular surgeons. The most common risk factor for type B aortic dissection is hypertension. The first line treatment for type B aortic dissection is aimed at reducing both heart rate and blood pressure and is referred to as anti-impulse therapy.

Should initial medical management fail or there is the involvement of a major branch of the aorta, vascular surgery may be needed for these type B dissections. Treatment may include thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) with or without extra-anatomic bypass such as carotid-carotid bypass, carotid-subclavian bypass, or subclavian-carotid transposition.

Visceral artery dissection

Visceral artery dissections are arterial dissections involving the superior mesenteric artery, celiac artery, renal arteries, hepatic artery and others. When they are an extension of an aortic dissection, this condition is managed simultaneously with aortic treatment. In isolation, visceral artery dissections are discovered incidentally in up to a third of patients and in these cases may be managed medically by a vascular surgeon. In cases where the dissection results in organ damage it is generally accepted by vascular surgeons that surgery is necessary. Surgical management strategies depend on the associated complications, surgical ability and patient preference.

Mesenteric ischemia

Mesenteric ischemia results from the acute or chronic obstruction of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). The SMA arises from the abdominal aorta and usually supplies blood from the distal duodenum through two-thirds of the transverse colon and the pancreas.

Chronic mesenteric ischemia

The symptoms of chronic mesenteric ischemia can be classified as abdominal angina which is abdominal pain which occurs a fixed period of time after eating. Due to this, patient's may avoid eating, resulting in unintended weight loss. The first surgical treatment is thought to be performed by R.S. Shaw and described in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1958. The procedure Shaw described is referred to as mesenteric endarterectomy. Since then, many advances in treatment have been made in minimally invasive, endovascular techniques including angioplasty and stenting.

Acute mesenteric ischemia

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) results from the sudden occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery.

Renovascular hypertension

The renal arteries supply oxygenated blood to the kidneys. The kidneys serve to filter the flood and control blood pressure through the renin-angiotensin system. One cause of resistant hypertension is atherosclerotic disease in the renal arteries and is generally referred to as renovascular hypertension. If renovascular hypertension is diagnosed and maximal medical fails to control high blood pressure, the vascular surgeon may offer surgical treatment, either endovascular or open surgical reconstruction.

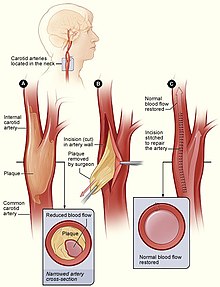

Cerebrovascular disease

Vascular surgeons are responsible for treating extracranial cerebrovascular disease as well as the interpretation of non-invasive vascular imaging relating to extracranial and intracranial circulation such as carotid ultrasonography and transcranial doppler. The most common of cerebrovascular conditions treated by vascular surgeons is carotid artery stenosis which is a narrowing of the carotid arteries and may be either clinically symptomatic or asymptomatic (silent). Carotid artery stenosis is caused by atherosclerosis whereby the buildup of atheromatous plaque inside the artery causes narrowing.

Symptoms of carotid artery stenosis can include transient ischemic attack or stroke. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid stenosis can be diagnosed with the aid of carotid duplex ultrasound which allows for the estimation of severity of narrowing as well as characterize the plaque. Treatment can include medical therapy, carotid endarterectomy or carotid stenting.

The Society for Vascular Surgery publishes clinical practice guidelines for the management of extracranial cerebrovascular disease. Less common diseases involving cerebral circulation treated by vascular surgeons include vertebrobasilar insufficiency, subclavian steal syndrome, carotid artery dissection, vertebral artery dissection, carotid body tumor and carotid artery aneurysm among others.

Peripheral artery disease

Peripheral artery disease PAD is the abnormal narrowing of the arteries which supply the limbs. Patients with this condition can present with intermittent claudication which is pain mainly in the calves and thighs while walking. If there is progression, a patient may also present with chronic limb threatening ischemia which encompasses pain at rest and non-healing wounds. Vascular surgeons are experts in the diagnosis, medical management, endovascular and open surgical treatment of PAD.

A vascular surgeon may diagnose PAD using a combination of history, physical exam and medical imaging. Medical imaging may include ankle-brachial index, doppler ultrasonography and computed tomography angiography, among others. Treatments are individualized and may include medical therapy, endovascular intervention or open surgical options including angioplasty, stenting, atherectomy, endarterectomy and vascular bypass, among others.

-

Illustration of atherosclerosis causing arterial obstruction which clinically presents at peripheral artery disease.

-

ABI testing is used by vascular surgeons in the diagnosis of PAD. The blood pressure in the arm and leg are compared as a ratio.

-

Angioplasty (pictured) and stenting are two endovascular treatments employed by the vascular surgeon.

Management of venous diseases

Chronic venous disease

Chronic venous insufficiency is the abnormal pooling of blood in the lower extremity venous system which can lead to reticular veins, varicose veins, chronic edema and inflammation among other things. Population data suggests that chronic venous insufficiency affects up to 40% of females and 17% of males. When chronic insufficiency leads to pain, swelling and skin changes it is referred to as chronic venous disease. Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is distinguished from post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) in that CVI is primarily an issue of valvular incompetence of the superficial or deep veins whereas PTS may occur as a long-term complication of deep venous thrombosis.

The vascular surgeon has several modalities to treat lower extremity venous disease which including medical, interventional and surgical procedures. For instance, venous ulceration may be treated with Unna's boots, superficial venous reflux with radiofrequency, laser ablation or vein stripping if indicated. When indicated, insufficiency in the deep veins may be treated with reconstruction of the venous valves with internal or external valvuloplasty.

Varicose veins

Lower extremity varicose veins is the condition in which the superficial veins become tortuous(snakelike) and dilated (enlarged) to greater than 3mm in the upright position. Incompetent or faulty valves are often present in these veins when investigated with duplex ultrasonography. Vascular treatments can include compression stockings, venous ablation or vein stripping, depending on specific patient presentation, severity of disease, among other things.

Nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions

Nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions (NIVL) include May-Thurner Syndrome (MTS) whereby there is compression of the left iliac venous outflow usually by the right iliac artery leading to left leg discomfort, pain, swelling and varicose veins. NIVL encompasses compression of the iliac veins on either the right or left side. Vascular surgeons may offer different treatment modalities depending on the patient presentation. Minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic options might include intravascular ultrasound, venography and iliac vein stenting whereas surgical management may be offered in refractory cases. Surgical management strategies involve reconstruction or bypass of the affected segment such as cross-pubic venous bypass, also known as the Palma procedure.

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the formation of thrombus in a deep vein. DVT is more likely to occur in the lower extremity than the upper extremity or jugular vein. When a DVT involves the pelvic and lower extremity veins it can sometimes be classified as an iliofemoral DVT. Some evidence to suggests that performing an intervention in these cases may be beneficial whereas other evidence does not. Overall, the data shows that there may be a reduction in the incidence in post-thrombotic syndrome in patients who undergo certain procedures for iliofemoral DVT but it is not without risks. A vascular surgeon may offer venogram, endovascular suction or mechanical thrombectomy and in some cases pharmacomechanical thrombectomy. Some lower extremity DVT can be severe enough to cause a condition called phlegmasia cerulea dolens or phlegmasia alba dolens and can be limb-threatening events. When phlegmasia is present, intervention is often warranted and may include venous thrombectomy.

Post-thrombotic syndrome

Post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) is a medical condition that sometimes occurs as a long-term complication of DVT and is characterized by long term edema and skin changes following DVT. Presenting symptoms may include itchiness, pain, cramps and paresthesia. It is estimated that between 20% and 50% of patients will experience some degree of PTS. A treatment strategy for PTS may involve the use of compression stockings.

Pulmonary embolism

Surgical management of an acute pulmonary embolism (pulmonary thrombectomy) is uncommon and has largely been abandoned because of poor long-term outcomes. However, recently, it has gone through a resurgence with the revision of the surgical technique and is thought to benefit certain people. Chronic pulmonary embolism leading to pulmonary hypertension (known as chronic thromboembolic hypertension) is treated with a surgical procedure known as a pulmonary thromboendarterectomy.

Compressive venopathies

Compression of large veins by adjacent structures or masses may lead to distinct clinical syndromes including May–Thurner syndrome (MTS), nutcracker syndrome and superior vena cava syndrome to name a few. Treatment modalities include venography, intravascular ultrasound and venous stenting as well as more invasive open venous reconstruction and bypass.

Management of hemodialysis access

Patients with chronic kidney disease may have progression of disease which requires renal replacement therapy to filter their blood. One strategy for this therapy is hemodialysis, which is a procedure that involves filtering a patient's blood to remove waste products and returning their blood back to them. One method which avoids repeated arterial trauma is to create an arteriovenous fistula (AVF). The first procedure described for this purpose is named the Cimino fistula, after one of the surgeons who first had success with it. Vascular surgeons may create an AVF for a patient as well as undertake minimally invasive procedures to ensure the fistula remains patent.

Management of vascular trauma

One way that vascular trauma may be understood is by categorizing vascular injury by three criteria: mechanism of injury, anatomical site of injury and contextual circumstances. Mechanism of injury refers to etiology, e.g. iatrogenic, blunt, penetrating, blast injury, etc. Anatomical site functionally refers to whether there is compressible versus non-compressible hemorrhage, while contextual circumstances refers to injuries sustained in the civilian or military realm. Each context can be further broken down: military into combatant vs. noncombatant and civil into urban vs rural trauma. This categorization scheme is of both epidemiologic and clinical significance. For instance, arterial injury in military combatants currently occurs predominantly in males in their twenties who are exposed to improvised explosive devices or gunshot wounds; whereas in the civilian realm, one study conducted in the United States showed the most common mechanisms to include motor vehicle collisions, firearm injuries, stab wounds and falls from heights.