| Different texts (and even different parts of this article) adopt slightly different definitions for the negative binomial distribution. They can be distinguished by whether the support starts at k = 0 or at k = r, whether p denotes the probability of a success or of a failure, and whether r represents success or failure, so identifying the specific parametrization used is crucial in any given text. | |||||||

|

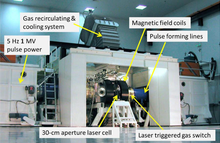

Probability mass function  The orange line represents the mean, which is equal to 10 in each of these plots; the green line shows the standard deviation. | |||||||

| Notation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters |

r > 0 — number of successes until the experiment is stopped (integer, but the definition can also be extended to reals) p ∈ [0,1] — success probability in each experiment (real) | ||||||

| Support | k ∈ { 0, 1, 2, 3, … } — number of failures | ||||||

| PMF | involving a binomial coefficient | ||||||

| CDF | the regularized incomplete beta function | ||||||

| Mean | |||||||

| Mode | |||||||

| Variance | |||||||

| Skewness | |||||||

| Ex. kurtosis | |||||||

| MGF | |||||||

| CF | |||||||

| PGF | |||||||

| Fisher information | |||||||

| Method of Moments |

| ||||||

In probability theory and statistics, the negative binomial distribution is a discrete probability distribution that models the number of failures in a sequence of independent and identically distributed Bernoulli trials before a specified (non-random) number of successes (denoted ) occurs. For example, we can define rolling a 6 on a die as a success, and rolling any other number as a failure, and ask how many failure rolls will occur before we see the third success (). In such a case, the probability distribution of the number of failures that appear will be a negative binomial distribution.

An alternative formulation is to model the number of total trials (instead of the number of failures). In fact, for a specified (non-random) number of successes (r), the number of failures (n − r) are random because the total trials (n) are random. For example, we could use the negative binomial distribution to model the number of days n (random) a certain machine works (specified by r) before it breaks down.

The Pascal distribution (after Blaise Pascal) and Polya distribution (for George Pólya) are special cases of the negative binomial distribution. A convention among engineers, climatologists, and others is to use "negative binomial" or "Pascal" for the case of an integer-valued stopping-time parameter () and use "Polya" for the real-valued case.

For occurrences of associated discrete events, like tornado outbreaks, the Polya distributions can be used to give more accurate models than the Poisson distribution by allowing the mean and variance to be different, unlike the Poisson. The negative binomial distribution has a variance , with the distribution becoming identical to Poisson in the limit for a given mean (i.e. when the failures are increasingly rare). This can make the distribution a useful overdispersed alternative to the Poisson distribution, for example for a robust modification of Poisson regression. In epidemiology, it has been used to model disease transmission for infectious diseases where the likely number of onward infections may vary considerably from individual to individual and from setting to setting. More generally, it may be appropriate where events have positively correlated occurrences causing a larger variance than if the occurrences were independent, due to a positive covariance term.

The term "negative binomial" is likely due to the fact that a certain binomial coefficient that appears in the formula for the probability mass function of the distribution can be written more simply with negative numbers.

Definitions

Imagine a sequence of independent Bernoulli trials: each trial has two potential outcomes called "success" and "failure." In each trial the probability of success is and of failure is . We observe this sequence until a predefined number of successes occurs. Then the random number of observed failures, , follows the negative binomial (or Pascal) distribution:

Probability mass function

The probability mass function of the negative binomial distribution is

where r is the number of successes, k is the number of failures, and p is the probability of success on each trial.

Here, the quantity in parentheses is the binomial coefficient, and is equal to

There are k failures chosen from k + r − 1 trials rather than k + r because the last of the k + r trials is by definition a success.

This quantity can alternatively be written in the following manner, explaining the name "negative binomial":

Note that by the last expression and the binomial series, for every 0 ≤ p < 1 and ,

hence the terms of the probability mass function indeed add up to one as below.

To understand the above definition of the probability mass function, note that the probability for every specific sequence of r successes and k failures is pr(1 − p)k, because the outcomes of the k + r trials are supposed to happen independently. Since the rth success always comes last, it remains to choose the k trials with failures out of the remaining k + r − 1 trials. The above binomial coefficient, due to its combinatorial interpretation, gives precisely the number of all these sequences of length k + r − 1.

Cumulative distribution function

The cumulative distribution function can be expressed in terms of the regularized incomplete beta function:

(This formula is using the same parameterization as in the article's table, with r the number of successes, and with the mean.)

It can also be expressed in terms of the cumulative distribution function of the binomial distribution:

Alternative formulations

Some sources may define the negative binomial distribution slightly differently from the primary one here. The most common variations are where the random variable X is counting different things. These variations can be seen in the table here:

|

|

X is counting... | Probability mass function | Formula | Alternate formula

(using equivalent binomial) |

Alternate formula

(simplified using: ) |

Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | k failures, given r successes |

|

||||

| 2 | n trials, given r successes | |||||

| 3 | n trials, given r failures | |||||

| 4 | k successes, given r failures | |||||

| - | k successes, given n trials | This is the binomial distribution not the negative binomial: | ||||

Each of the four definitions of the negative binomial distribution can be expressed in slightly different but equivalent ways. The first alternative formulation is simply an equivalent form of the binomial coefficient, that is: . The second alternate formulation somewhat simplifies the expression by recognizing that the total number of trials is simply the number of successes and failures, that is: . These second formulations may be more intuitive to understand, however they are perhaps less practical as they have more terms.

- The definition where X is the number of n trials that occur for a given number of r successes is similar to the primary definition, except that the number of trials is given instead of the number of failures. This adds r to the value of the random variable, shifting its support and mean.

- The definitiond where X is the number of k successes (or n trials) that occur for a given number of r failures is similar to the primary definition used in this article, except that numbers of failures and successes are switched when considering what is being counted and what is given. Note however, that p still refers to the probability of "success".

- The definition of the negative binomial distribution can be extended to the case where the parameter r can take on a positive real value. Although it is impossible to visualize a non-integer number of "failures", we can still formally define the distribution through its probability mass function. The problem of extending the definition to real-valued (positive) r boils down to extending the binomial coefficient to its real-valued counterpart, based on the gamma function:

- After substituting this expression in the original definition, we say that X has a negative binomial (or Pólya) distribution if it has a probability mass function:

- Here r is a real, positive number.

In negative binomial regression, the distribution is specified in terms of its mean, , which is then related to explanatory variables as in linear regression or other generalized linear models. From the expression for the mean m, one can derive and . Then, substituting these expressions in the one for the probability mass function when r is real-valued, yields this parametrization of the probability mass function in terms of m:

The variance can then be written as . Some authors prefer to set , and express the variance as . In this context, and depending on the author, either the parameter r or its reciprocal α is referred to as the "dispersion parameter", "shape parameter" or "clustering coefficient", or the "heterogeneity" or "aggregation" parameter. The term "aggregation" is particularly used in ecology when describing counts of individual organisms. Decrease of the aggregation parameter r towards zero corresponds to increasing aggregation of the organisms; increase of r towards infinity corresponds to absence of aggregation, as can be described by Poisson regression.

Alternative parameterizations

Sometimes the distribution is parameterized in terms of its mean μ and variance σ2:

Examples

Length of hospital stay

Hospital length of stay is an example of real-world data that can be modelled well with a negative binomial distribution via negative binomial regression.

Selling candy

Pat Collis is required to sell candy bars to raise money for the 6th grade field trip. Pat is (somewhat harshly) not supposed to return home until five candy bars have been sold. So the child goes door to door, selling candy bars. At each house, there is a 0.6 probability of selling one candy bar and a 0.4 probability of selling nothing.

What's the probability of selling the last candy bar at the nth house?

Successfully selling candy enough times is what defines our stopping criterion (as opposed to failing to sell it), so k in this case represents the number of failures and r represents the number of successes. Recall that the NegBin(r, p) distribution describes the probability of k failures and r successes in k + r Bernoulli(p) trials with success on the last trial. Selling five candy bars means getting five successes. The number of trials (i.e. houses) this takes is therefore k + 5 = n. The random variable we are interested in is the number of houses, so we substitute k = n − 5 into a NegBin(5, 0.4) mass function and obtain the following mass function of the distribution of houses (for n ≥ 5):

What's the probability that Pat finishes on the tenth house?

What's the probability that Pat finishes on or before reaching the eighth house?

To finish on or before the eighth house, Pat must finish at the fifth, sixth, seventh, or eighth house. Sum those probabilities:

What's the probability that Pat exhausts all 30 houses that happen to stand in the neighborhood?

This can be expressed as the probability that Pat does not finish on the fifth through the thirtieth house:

Because of the rather high probability that Pat will sell to each house (60 percent), the probability of her NOT fulfilling her quest is vanishingly slim.

Properties

Expectation

The expected total number of trials needed to see r successes is . Thus, the expected number of failures would be this value, minus the successes:

Expectation of successes

The expected total number of failures in a negative binomial distribution with parameters (r, p) is r(1 − p)/p. To see this, imagine an experiment simulating the negative binomial is performed many times. That is, a set of trials is performed until r successes are obtained, then another set of trials, and then another etc. Write down the number of trials performed in each experiment: a, b, c, ... and set a + b + c + ... = N. Now we would expect about Np successes in total. Say the experiment was performed n times. Then there are nr successes in total. So we would expect nr = Np, so N/n = r/p. See that N/n is just the average number of trials per experiment. That is what we mean by "expectation". The average number of failures per experiment is N/n − r = r/p − r = r(1 − p)/p. This agrees with the mean given in the box on the right-hand side of this page.

A rigorous derivation can be done by representing the negative binomial distribution as the sum of waiting times. Let with the convention represents the number of failures observed before successes with the probability of success being . And let where represents the number of failures before seeing a success. We can think of as the waiting time (number of failures) between the th and th success. Thus

The mean is

which follows from the fact .

Variance

When counting the number of failures before the r-th success, the variance is r(1 − p)/p2. When counting the number of successes before the r-th failure, as in alternative formulation (3) above, the variance is rp/(1 − p)2.

Relation to the binomial theorem

Suppose Y is a random variable with a binomial distribution with parameters n and p. Assume p + q = 1, with p, q ≥ 0, then

Using Newton's binomial theorem, this can equally be written as:

in which the upper bound of summation is infinite. In this case, the binomial coefficient

is defined when n is a real number, instead of just a positive integer. But in our case of the binomial distribution it is zero when k > n. We can then say, for example

Now suppose r > 0 and we use a negative exponent:

Then all of the terms are positive, and the term

is just the probability that the number of failures before the rth success is equal to k, provided r is an integer. (If r is a negative non-integer, so that the exponent is a positive non-integer, then some of the terms in the sum above are negative, so we do not have a probability distribution on the set of all nonnegative integers.)

Now we also allow non-integer values of r. Then we have a proper negative binomial distribution, which is a generalization of the Pascal distribution, which coincides with the Pascal distribution when r happens to be a positive integer.

Recall from above that

- The sum of independent negative-binomially distributed random variables r1 and r2 with the same value for parameter p is negative-binomially distributed with the same p but with r-value r1 + r2.

This property persists when the definition is thus generalized, and affords a quick way to see that the negative binomial distribution is infinitely divisible.

Recurrence relations

The following recurrence relations hold:

For the probability mass function

For the moments

For the cumulants

Related distributions

- The geometric distribution (on { 0, 1, 2, 3, ... }) is a special case of the negative binomial distribution, with

- The negative binomial distribution is a special case of the discrete phase-type distribution.

- The negative binomial distribution is a special case of discrete compound Poisson distribution.

Poisson distribution

Consider a sequence of negative binomial random variables where the stopping parameter r goes to infinity, while the probability p of success in each trial goes to one, in such a way as to keep the mean of the distribution (i.e. the expected number of failures) constant. Denoting this mean as λ, the parameter p will be p = r/(r + λ)

Under this parametrization the probability mass function will be

Now if we consider the limit as r → ∞, the second factor will converge to one, and the third to the exponent function:

which is the mass function of a Poisson-distributed random variable with expected value λ.

In other words, the alternatively parameterized negative binomial distribution converges to the Poisson distribution and r controls the deviation from the Poisson. This makes the negative binomial distribution suitable as a robust alternative to the Poisson, which approaches the Poisson for large r, but which has larger variance than the Poisson for small r.

Gamma–Poisson mixture

The negative binomial distribution also arises as a continuous mixture of Poisson distributions (i.e. a compound probability distribution) where the mixing distribution of the Poisson rate is a gamma distribution. That is, we can view the negative binomial as a Poisson(λ) distribution, where λ is itself a random variable, distributed as a gamma distribution with shape r and scale θ = (1 − p)/p or correspondingly rate β = p/(1 − p).

To display the intuition behind this statement, consider two independent Poisson processes, "Success" and "Failure", with intensities p and 1 − p. Together, the Success and Failure processes are equivalent to a single Poisson process of intensity 1, where an occurrence of the process is a success if a corresponding independent coin toss comes up heads with probability p; otherwise, it is a failure. If r is a counting number, the coin tosses show that the count of successes before the rth failure follows a negative binomial distribution with parameters r and p. The count is also, however, the count of the Success Poisson process at the random time T of the rth occurrence in the Failure Poisson process. The Success count follows a Poisson distribution with mean pT, where T is the waiting time for r occurrences in a Poisson process of intensity 1 − p, i.e., T is gamma-distributed with shape parameter r and intensity 1 − p. Thus, the negative binomial distribution is equivalent to a Poisson distribution with mean pT, where the random variate T is gamma-distributed with shape parameter r and intensity (1 − p). The preceding paragraph follows, because λ = pT is gamma-distributed with shape parameter r and intensity (1 − p)/p.

The following formal derivation (which does not depend on r being a counting number) confirms the intuition.

Because of this, the negative binomial distribution is also known as the gamma–Poisson (mixture) distribution. The negative binomial distribution was originally derived as a limiting case of the gamma-Poisson distribution.

Distribution of a sum of geometrically distributed random variables

If Yr is a random variable following the negative binomial distribution with parameters r and p, and support {0, 1, 2, ...}, then Yr is a sum of r independent variables following the geometric distribution (on {0, 1, 2, ...}) with parameter p. As a result of the central limit theorem, Yr (properly scaled and shifted) is therefore approximately normal for sufficiently large r.

Furthermore, if Bs+r is a random variable following the binomial distribution with parameters s + r and p, then

In this sense, the negative binomial distribution is the "inverse" of the binomial distribution.

The sum of independent negative-binomially distributed random variables r1 and r2 with the same value for parameter p is negative-binomially distributed with the same p but with r-value r1 + r2.

The negative binomial distribution is infinitely divisible, i.e., if Y has a negative binomial distribution, then for any positive integer n, there exist independent identically distributed random variables Y1, ..., Yn whose sum has the same distribution that Y has.

Representation as compound Poisson distribution

The negative binomial distribution NB(r,p) can be represented as a compound Poisson distribution: Let {Yn, n ∈ 0 denote a sequence of independent and identically distributed random variables, each one having the logarithmic series distribution Log(p), with probability mass function

Let N be a random variable, independent of the sequence, and suppose that N has a Poisson distribution with mean λ = −r ln(1 − p). Then the random sum

is NB(r,p)-distributed. To prove this, we calculate the probability generating function GX of X, which is the composition of the probability generating functions GN and GY1. Using

and

we obtain

which is the probability generating function of the NB(r,p) distribution.

The following table describes four distributions related to the number of successes in a sequence of draws:

| With replacements | No replacements | |

|---|---|---|

| Given number of draws | binomial distribution | hypergeometric distribution |

| Given number of failures | negative binomial distribution | negative hypergeometric distribution |

(a,b,0) class of distributions

The negative binomial, along with the Poisson and binomial distributions, is a member of the (a,b,0) class of distributions. All three of these distributions are special cases of the Panjer distribution. They are also members of a natural exponential family.

Statistical inference

Parameter estimation

MVUE for p

Suppose p is unknown and an experiment is conducted where it is decided ahead of time that sampling will continue until r successes are found. A sufficient statistic for the experiment is k, the number of failures.

In estimating p, the minimum variance unbiased estimator is

Maximum likelihood estimation

When r is known, the maximum likelihood estimate of p is

but this is a biased estimate. Its inverse (r + k)/r, is an unbiased estimate of 1/p, however.

When r is unknown, the maximum likelihood estimator for p and r together only exists for samples for which the sample variance is larger than the sample mean. The likelihood function for N iid observations (k1, ..., kN) is

from which we calculate the log-likelihood function

To find the maximum we take the partial derivatives with respect to r and p and set them equal to zero:

- and

where

- is the digamma function.

Solving the first equation for p gives:

Substituting this in the second equation gives:

This equation cannot be solved for r in closed form. If a numerical solution is desired, an iterative technique such as Newton's method can be used. Alternatively, the expectation–maximization algorithm can be used.

Occurrence and applications

Waiting time in a Bernoulli process

For the special case where r is an integer, the negative binomial distribution is known as the Pascal distribution. It is the probability distribution of a certain number of failures and successes in a series of independent and identically distributed Bernoulli trials. For k + r Bernoulli trials with success probability p, the negative binomial gives the probability of k successes and r failures, with a failure on the last trial. In other words, the negative binomial distribution is the probability distribution of the number of successes before the rth failure in a Bernoulli process, with probability p of successes on each trial. A Bernoulli process is a discrete time process, and so the number of trials, failures, and successes are integers.

Consider the following example. Suppose we repeatedly throw a die, and consider a 1 to be a failure. The probability of success on each trial is 5/6. The number of successes before the third failure belongs to the infinite set { 0, 1, 2, 3, ... }. That number of successes is a negative-binomially distributed random variable.

When r = 1 we get the probability distribution of number of successes before the first failure (i.e. the probability of the first failure occurring on the (k + 1)st trial), which is a geometric distribution:

Overdispersed Poisson

The negative binomial distribution, especially in its alternative parameterization described above, can be used as an alternative to the Poisson distribution. It is especially useful for discrete data over an unbounded positive range whose sample variance exceeds the sample mean. In such cases, the observations are overdispersed with respect to a Poisson distribution, for which the mean is equal to the variance. Hence a Poisson distribution is not an appropriate model. Since the negative binomial distribution has one more parameter than the Poisson, the second parameter can be used to adjust the variance independently of the mean. See Cumulants of some discrete probability distributions.

An application of this is to annual counts of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic or to monthly to 6-monthly counts of wintertime extratropical cyclones over Europe, for which the variance is greater than the mean. In the case of modest overdispersion, this may produce substantially similar results to an overdispersed Poisson distribution.

The negative binomial distribution is also commonly used to model data in the form of discrete sequence read counts from high-throughput RNA and DNA sequencing experiments.

Multiplicity Observations (Physics)

The negative binomial distribution has been the most effective statistical model for a broad range of multiplicity observations in particle collision experiments, e.g., and is argued to be a scale-invariant property of matter, providing the best fit for astronomical observations, where it predicts the number of galaxies in a region of space. The phenomenological justification for the effectiveness of the negative binomial distribution in these contexts remained unknown for fifty years, since their first observation in 1973. In 2023, a proof from first principles was eventually demonstrated by Scott V. Tezlaf, where it was shown that the negative binomial distribution emerges from symmetries in the dynamical equations of a canonical ensemble of particles in Minkowski space. Roughly, given an expected number of trials and expected number of successes , where

an isomorphic set of equations can be identified with the parameters of a relativistic current density of a canonical ensemble of massive particles, via

where is the rest density, is the relativistic mean square density, is the relativistic mean square current density, and , where is the mean square speed of the particle ensemble and is the speed of light—such that one can establish the following bijective map:

A rigorous alternative proof of the above correspondence has also been demonstrated through quantum mechanics via the Feynman path integral.

![{\displaystyle r={\frac {E[X]^{2}}{V[X]-E[X]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9574276fc676473c29b7f96d37f03fcfddade97f)

![{\displaystyle p=1-{\frac {E[X]}{V[X]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/087568b1d5fa521418d2f628120beb5ba3bfb985)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&{\frac {(k+r-1)\dotsm (r)}{k!}}\\[10pt]={}&(-1)^{k}{\frac {\overbrace {(-r)(-r-1)(-r-2)\dotsm (-r-k+1)} ^{k{\text{ factors}}}}{k!}}=(-1)^{k}{\binom {-r}{{\phantom {-}}k}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b40cf970eaae3d29fb34f8a0cdca08cb41cacb89)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&p={\frac {\mu }{\sigma ^{2}}},\\[6pt]&r={\frac {\mu ^{2}}{\sigma ^{2}-\mu }},\\[3pt]&\Pr(X=k)={k+{\frac {\mu ^{2}}{\sigma ^{2}-\mu }}-1 \choose r-1}\left({\frac {\sigma ^{2}-\mu }{\sigma ^{2}}}\right)^{k}\left({\frac {\mu }{\sigma ^{2}}}\right)^{\mu ^{2}/(\sigma ^{2}-\mu )}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a79f93fb7f7ff058dbe6ac0c4f59521fb416b767)

![{\displaystyle E[\operatorname {NB} (r,p)]={\frac {r}{p}}-r={\frac {r(1-p)}{p}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5519279a74d51004d5f094949e4e2bee698e8cbb)

![{\displaystyle E[X_{r}]=E[Y_{1}]+E[Y_{2}]+\cdots +E[Y_{r}]={\frac {r(1-p)}{p}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/67a282500b0cea995c329656b9c7a2f9d6384210)

![{\displaystyle E[Y_{i}]=(1-p)/p}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2ef35e8cb49f23b9b4dee58ad254505a17a0aae0)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{cases}(k+1)\Pr(X=k+1)-p\Pr(X=k)(k+r)=0,\\[5pt]\Pr(X=0)=(1-p)^{r}.\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9a3701d0579cb79afe77cc31d1c8067dd0946056)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&\int _{0}^{\infty }f_{\operatorname {Poisson} (\lambda )}(k)\times f_{\operatorname {Gamma} \left(r,\,{\frac {p}{1-p}}\right)}(\lambda )\,\mathrm {d} \lambda \\[8pt]={}&\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\lambda ^{k}}{k!}}e^{-\lambda }\times {\frac {1}{\Gamma (r)}}\left({\frac {p}{1-p}}\lambda \right)^{r-1}e^{-{\frac {p}{1-p}}\lambda }\,\left({\frac {p}{1-p}}\,\mathrm {d} \lambda \right)\\[8pt]={}&\left({\frac {p}{1-p}}\right)^{r}{\frac {1}{k!\,\Gamma (r)}}\int _{0}^{\infty }\lambda ^{r+k-1}e^{-\lambda {\frac {p+1-p}{1-p}}}\;\mathrm {d} \lambda \\[8pt]={}&\left({\frac {p}{1-p}}\right)^{r}{\frac {1}{k!\,\Gamma (r)}}\Gamma (r+k)(1-p)^{k+r}\int _{0}^{\infty }f_{\operatorname {Gamma} \left(k+r,{\frac {1}{1-p}}\right)}(\lambda )\;\mathrm {d} \lambda \\[8pt]={}&{\frac {\Gamma (r+k)}{k!\;\Gamma (r)}}\;(1-p)^{k}\,p^{r}\\[8pt]={}&f(k;r,p).\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c91b855c201e50d7a21d7d4814a7bf1a290b17a6)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\Pr(Y_{r}\leq s)&{}=1-I_{p}(s+1,r)\\[5pt]&{}=1-I_{p}((s+r)-(r-1),(r-1)+1)\\[5pt]&{}=1-\Pr(B_{s+r}\leq r-1)\\[5pt]&{}=\Pr(B_{s+r}\geq r)\\[5pt]&{}=\Pr({\text{after }}s+r{\text{ trials, there are at least }}r{\text{ successes}}).\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f9f37213febcea5a4f29b1ffe3e441b39a9563c2)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}G_{X}(z)&=G_{N}(G_{Y_{1}}(z))\\[4pt]&=\exp {\biggl (}\lambda {\biggl (}{\frac {\ln(1-pz)}{\ln(1-p)}}-1{\biggr )}{\biggr )}\\[4pt]&=\exp {\bigl (}-r(\ln(1-pz)-\ln(1-p)){\bigr )}\\[4pt]&={\biggl (}{\frac {1-p}{1-pz}}{\biggr )}^{r},\qquad |z|<{\frac {1}{p}},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/58ac77a8c8e8d8e302a1f7061d89c1933b09c683)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial \ell (r,p)}{\partial p}}=-\left[\sum _{i=1}^{N}k_{i}{\frac {1}{1-p}}\right]+Nr{\frac {1}{p}}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4ab2d7ba5e059b2ab00365733c5913d9c8d225c2)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial \ell (r,p)}{\partial r}}=\left[\sum _{i=1}^{N}\psi (k_{i}+r)\right]-N\psi (r)+N\ln(p)=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d33253aac20e10c307494e623b9d239b1bf6e5d)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\partial \ell (r,p)}{\partial r}}=\left[\sum _{i=1}^{N}\psi (k_{i}+r)\right]-N\psi (r)+N\ln \left({\frac {r}{r+\sum _{i=1}^{N}k_{i}/N}}\right)=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c677e2362cc19e7aad49451214500a1ccccb5f95)