The theory of imperialism refers to a range of theoretical approaches to understanding the expansion of capitalism into new areas, the unequal development of different countries, and economic systems that may lead to the dominance of some countries over others. These theories are considered distinct from other uses of the word imperialism which refer to the general tendency for empires throughout history to seek power and territorial expansion. The theory of imperialism is often associated with Marxist economics, but many theories were developed by non-Marxists. Most theories of imperialism, with the notable exception of ultra-imperialism, hold that imperialist exploitation leads to warfare, colonization, and international inequality.

Early theories

Marx

While most theories of imperialism are associated with Marxism, Karl Marx never used the term imperialism, nor wrote about any comparable theories. However many writers have suggested that ideas integral to later theories of imperialism were present in Marx's writings. For example, Frank Richards in 1979 noted that already in the Grundrisse "Marx anticipated the Imperialist epoch." Lucia Pradella has argued that there was already an immanent theory of imperialism in Marx's unpublished studies of the world economy.

Marx's theory of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall was considered particularly important to later theorists of imperialism, as it seemed to explain why capitalist enterprises consistently require areas of higher profitability to expand into. Marx also noted the need for the capitalist mode of production as a whole to constantly expand into new areas, writing that "‘The need of a constantly expanding market chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere."

Marx also argued that certain colonial societies’ backwardness could only be explained through external intervention. In Ireland Marx argued that English repression had forced Irish society to remain in a pre-capitalist mode. In India Marx was critical of the role of merchant capital, which he saw as preventing societal transformation where industrial capital might otherwise bring progressive change. Marx's writings on colonial societies are often considered by modern Marxists to contain contradictions or incorrect predictions, even if most agree he laid the foundation for later understandings of imperialism.

Hobson

J. A. Hobson was an English liberal economist whose theory of imperialism was extremely influential among Marxist economists, particularly Vladimir Lenin, and Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy. Hobson is best remembered for his Imperialism: A Study, published 1902, which associated imperialism with the growth of monopoly capital and a subsequent underconsumption crisis. Hobson argued that the growth of monopolies within capitalist countries tends to concentrate capital in fewer hands, leading to an increase in savings, and a corresponding decline in investment. This excessive saving relative to investment leads to a chronic lack of demand, which can be relieved either through finding new territories to invest into, or finding new markets with greater demand for goods. These two drives result in a need to safeguard the monopoly's foreign investments, or break up existing protections to better penetrate foreign markets, adding to the pressure to annex foreign countries.

Hobson's opposition to imperialism was informed by his liberalism, particularly the radical liberalism of Richard Cobden and Herbert Spencer. He alleged that imperialism was bad business due to high risk and high costs, as well as being bad for democracy, and morally reprehensible. He claimed that imperialism only benefited a select few individuals, rather than the majority of British citizens, or even the majority of British capitalists. As an alternative, he proposed a proto-Keynesian solution of stimulating demand through the partial redistribution of income and wealth within home markets.

Hobson's ideas were enormously influential, and most later theories of imperialism were in some way shaped by Hobson's arguments. Historians Peter Duignan and Lewis H. Gann argue that Hobson had an enormous influence in the early 20th century among people from all over the world:

Hobson's ideas were not entirely original; however his hatred of moneyed men and monopolies, his loathing of secret compacts and public bluster, fused all existing indictments of imperialism into one coherent system....His ideas influenced German nationalist opponents of the British Empire as well as French Anglophobes and Marxists; they colored the thoughts of American liberals and isolationist critics of colonialism. In days to come they were to contribute to American distrust of Western Europe and of the British Empire. Hobson helped make the British averse to the exercise of colonial rule; he provided indigenous nationalists in Asia and Africa with the ammunition to resist rule from Europe

— Peter Duignan and Lewis H. Gann, Burden of Empire: An Appraisal of Western Colonialism in Africa South of the Sahara page 59.

By 1911, Hobson had largely reversed his position on imperialism, as he was convinced by arguments from his fellow radical liberals Joseph Schumpeter, Thorstein Veblen, and Norman Angell, who argued that imperialism itself was mutually beneficial for all societies involved, provided it was not perpetrated by a power with a fundamentally aristocratic, militaristic nature. This distinction between a benign "industrial imperialism" and a harmful "militarist imperialism" was similar to the earlier ideas of Spencer, and would prove foundational to later non-Marxist histories of imperialism.

Trotsky

Leon Trotsky began expressing his theory of uneven and combined development in 1906, though the concept would only become prominent in his writing from 1927 onwards. Trotsky observed that different countries developed and advanced to a large extent independently from each other, in ways which were quantitatively unequal (e.g. the local rate and scope of economic growth and population growth) and qualitatively different (e.g. nationally specific cultures and geographical features). In other words, countries had their own specific national history with national peculiarities. At the same time, all the different countries did not exist in complete isolation from each other; they were also interdependent parts of a world society, a larger totality, in which they all co-existed together, in which they shared many characteristics, and in which they influenced each other through processes of cultural diffusion, trade, political relations and various "spill-over effects" from one country to another.

In The History of the Russian Revolution, published in 1932, Trotsky tied his theory of development to a theory of imperialism. In Trotsky's theory of imperialism, the domination of one country by another does not mean that the dominated country is prevented from development altogether, but rather that it develops mainly according to the requirements of the dominating country.

Trotsky's later writings show that uneven and combined development is less of a theory of development economics, and more of a general dialectical category that governs personal, historical, and even biological development. The theory was nonetheless influential in imperialism studies, as it may have influenced passages in Rudolf Hilferding's Finance Capital, as well as later theories of economic geography.

Hilferding

Rudolf Hilferding's Finance Capital, published in 1910, is considered the first of the "classical" Marxist theories of imperialism which would be codified and popularized by Nikolai Bukharin and Lenin. Hilferding began his analysis of imperialism with a very thorough treatment of monetary economics and an analysis of the rise of joint stock companies. The rise of joint stock companies, as well as banking monopolies, led to unprecedented concentrations of capital. As monopolies took direct control of buying and selling, opportunities for investment in commerce declined. This had the effect of essentially forcing banking monopolies to invest directly in production, as Hilferding writes:

An ever-increasing part of the capital of industry does not belong to the industrialists who use it. They are able to dispose over capital only through the banks, which represent the owners. On the other side, the banks have to invest an ever-increasing part of their capital in industry, and in this way they become to a greater and greater extent industrial capitalists. I call bank capital, that is, capital in money form which is actually transformed in this way into industrial capital, finance capital.

— Hilferding, Finance Capital page 225.

Hilferding's finance capital is best understood as a fraction of capital in which the functions of financial capital and industrial capital are united. The era of finance capital would be one marked by large companies which are able to raise money from a wide range of sources. These finance-capital-heavy companies would then seek to expand into a large area of operations in order to make the most efficient use of natural resources and, having monopolised that area, erect tariffs on exported goods in order to exploit their monopoly position. This process is summarized by Hilferding as follows:

The policy of finance capital has three objectives: (1) to establish the largest possible economic territory; (2) to close this territory to foreign competition by a wall of protective tariffs, and consequently (3) to reserve it as an area of exploitation for the national monopolistic combines.

— Hilferding, Finance Capital page 226.

To Hilferding, monopolies exploited all consumers within their protected areas, not just colonial subjects, however he did believe that "[v]iolent methods are of the essence of colonial policy, without which it would lose its capitalist rationale." Thus like Hobson, Hilferding believed that imperialism benefits only a minority of the bourgeoisie.

While acknowledged by Lenin as an important contributor to the theory of Imperialism, Hilferding's position as finance minister in the Weimar Republic from 1923 discredited him in the eyes of many socialists. Hilferding's influence on later theories was thus largely transmitted through Lenin's work, as his own work was rarely acknowledged or translated, and went out of print several times.

Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg followed Marx's interpretation of the expansion of the capitalist mode of production very closely. In The Accumulation of Capital, published in 1913, Luxemburg drew on a close reading of Marx to make several arguments about Imperialism. First, she argued that Marx had made a logical error in his analysis of extended reproduction, which would make it impossible for goods to be sold at prices high enough to cover the costs of reinvestment, meaning that buyers external to the capitalist system would be required for capitalist production to remain profitable. Second, she argued that capitalism is surrounded by pre-capitalist economies, and that competition forces capitalist firms to expand into these economies and ultimately destroy them. These competing drives to exploit and destroy pre-capitalist societies led Luxemburg to the conclusion that capitalism would end once it ran out of pre-capitalist societies to exploit, leading her to campaign against war and colonialism.

Luxemburg's underconsumptionist argument was heavily criticised by many Marxist and non-Marxist economists as too crude, although it gained a noted defender in György Lukács. While Luxemburg's analysis of imperialism did not prove to be as influential as other theories, she has been praised for urging early Marxists to focus on the Global South rather than solely on advanced, industrialized countries.

Kautsky

Prior to the First World War Hobson, as well as Karl Liebknecht had theorized that imperialist states could, in the future, potentially transform into interstate cartels which could more efficiently exploit the remainder of the world without causing warfare in Europe. In 1914 Karl Kautsky expressed a similar idea, coining the term ultra-imperialism, or a stage of peaceful cooperation between imperialist powers, where countries would forego arms races and limit competition. This implied that warfare is not essential to capitalism, and that socialists should agitate towards a peaceful capitalism, rather than an end to imperialism.

Kautsky's idea is often best remembered for Lenin's frequent criticism of the concept. In an introduction to Bukharin's Imperialism and World Economy for example, Lenin contended that "in the abstract one can think of such a phase. In practice, however, he who denies the sharp tasks of to-day in the name of dreams about soft tasks of the future becomes an opportunist".

Despite being sharply criticized in its own day, ultra-imperialism has been revived to describe instances of inter-imperialist cooperation in later years, such as cooperation among capitalist states in the Cold War. Commentators have also pointed out similarities between Kautsky's theory and Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri's theory of empire, however the authors dispute this.

Bukharin

Nikolai Bukharin's Imperialism and World Economy, written in 1915, primarily served to clarify and refine the earlier ideas of Hilferding, and frame them in a more consistently anti-imperialist light. Bukharin's main difference with Hilferding was that rather than a single process that leads to imperialism (the increasing concentration of finance capital), Bukharin saw two competing processes that would create friction and warfare. These were the "internationalization" of capital (the growing interdependence of the world economy), and the "nationalization" of capital (the division of capital into national power blocs). The result of these tendencies would be large national blocs of capital competing within a world economy, or in Bukharin's words:

[V]arious spheres of the concentration and organization process stimulate each other, creating a very strong tendency towards transforming the entire national economy into one gigantic combined enterprise under the tutelage of the financial kings and the capitalist state, an enterprise which monopolizes the national market. . . . It follows that world capitalism, the world system of production, assumes in our times the following aspect: a few consolidated, organized economic bodies (‘the great civilized powers’) on the one hand, and a periphery of underdeveloped countries with a semi-agrarian or agrarian system on the other.

— Bukharin, Imperialism and World Economy pages 73-74.

Competition and other independent market forces would, in this system, be relatively restrained at the national level, but much more disruptive at the world level. Monopoly was thus not an end to competition, but rather each successive intensification of Monopoly capital into larger blocs would entail a much more intensive form of competition, at ever larger scales.

Bukharin's theory of imperialism is also notable for reintroducing the theory of a labor aristocracy in order to explain the perceived failure of the Second International. Bukharin argued that increased superprofits from the colonies constituted the basis for higher wages in advanced countries, causing some workers to identify with the interests of their state rather than their class. The same idea would be taken up by Lenin.

Lenin

Despite being a relatively small text which sought only to summarize the earlier ideas of Hobson, Hilferdung and Bukharin, Vladimir Lenin's pamphlet Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism is easily the most influential, widely read text on the subject of imperialism.

Lenin's argument differs from previous writers in that rather than viewing imperialism as a distinct policy of certain countries and states (as Bukharin had done, for example), he saw imperialism as a new historical stage in capitalist development, and all imperialist policies were simply characteristic of this stage. The progression into this stage would be complete when:

- "(1) the concentration of production and capital has developed to such a high stage that it has created monopolies which play a decisive role in economic life"

- "(2) the merging of bank capital with industrial capital, and the creation, on the basis of this ‘finance capital’ of a financial oligarchy"

- "(3) the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance"

- "(4) the formation of international monopolist capitalist combines which share the world among themselves"

- "(5) the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed."

The importance of Lenin's pamphlet has been debated by later writers due to its status within the communist movement. Some, such as Anthony Brewer, have argued that Imperialism is a "popular outline" which has been unfairly treated as a "sacred text", and that many arguments (such as Lenin's contention that industry requires capital export to survive) are not as well developed as in his contemporaries’ work. Others have argued that Lenin's prefiguration of a core-periphery divide and use of the term "world system" were crucial to the later development of dependency theory and world-systems theory.

Postwar theories

Baran and Sweezy

Between the publication of Lenin's Imperialism in 1916 and Paul Sweezy's The Theory of Capitalist Development in 1942 and Paul A. Baran's Political Economy of Growth in 1957, there was a notable lack of development in the Marxist theory of imperialism, best explained by the elevation of Lenin's work to the status of Marxist orthodoxy. Like Hobson, Baran and Sweezy employed an underconsumptionist line of reasoning to argue that infinite growth of the capitalist system is impossible. They argued that as capitalism develops, wages tend to decline, and with them, the total level of consumption. The ability for consumption to absorb the total productive output of society is therefore limited, and this output must then be reinvested elsewhere. Since Sweezy implies that it would be impossible to continuously reinvest in productive machinery (which would only increase the output of consumer goods, adding to the initial problem), there is an irreconcilable contradiction between the need to increase investments to absorb surplus output, and the need to reduce overall output to match consumer demand. This problem can, however, be delayed through investments in unproductive aspects of society (such as the military), or through capital export.

In addition to this underconsumptionist argument, Baran and Sweezy argued that there are two motives for investment in industry: increasing productive output, and introducing new productive techniques. While in conventional competitive capitalism, any firm which does not introduce new productive techniques will usually fall behind and become unprofitable, in monopoly capitalism, there is actually no incentive to introduce new productive techniques, as there are no rivals to gain a competitive advantage over, and thus no reason to render one's own machinery obsolete. This is a key difference with the earlier "classical" theories of imperialism, especially Bukharin, as here monopoly does not represent an intensification of competition but rather its total suppression. Baran and Sweezy also rejected the earlier claim that all national industries would form a single "national cartel," instead noting that there tended to be a number of monopoly companies within a country: just enough to maintain a "balance of power."

The connection to imperialist violence then, is that most western nations have sought to solve their underconsumption crises by investing heavily into military armaments, to the exclusion of all other forms of investment. In addition to this, capital exports into the less concretely divided areas of the world have increased, and monopoly companies seek protection from their parent states in order to secure these foreign investments. To Baran and Sweezy, these two factors explain imperialist warfare and the dominance of developed countries.

Conversely, they explain the underdevelopment of poor nations through trade flows. Trade flows serve to provide cheap primary goods to the advanced countries, while local manufacturing in underdeveloped countries is discouraged through competition with goods from the advanced countries. Baran and Sweezy were the first economists to treat the development of capitalism in the advanced countries as different from its development in the underdeveloped countries, an outlook influenced by the philosophy of Frantz Fanon and Herbert Marcuse.

In doing so Baran and Sweezy were the first theorists to popularize the idea that imperialism is not a force which is both progressive and destructive, but rather that it is destructive as well as a barrier to development in many countries. This conclusion proved influential, and lead to the "underdevelopment school" of economics, however their reliance on underconsumptionist logic has been criticised as empirically flawed. Their theory also attracted renewed interest in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah, former president of Ghana (1960–66), coined the term Neocolonialism, which appeared in the 1963 preamble of the Organisation of African Unity Charter, and was the title of his 1965 book Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism. Nkrumah's theory was largely based in Lenin's Imperialism, and followed similar themes to the classical Marxist theories of imperialism, describing imperialism as the result of a need to export crises to areas outside Europe. However unlike the classical Marxist theories, Nkrumah saw imperialism as holding back the development of the colonized world, writing:

In place of colonialism, as the main instrument of imperialism, we have today neo-colonialism... [which] like colonialism, is an attempt to export the social conflicts of the capitalist countries... The result of neo-colonialism is that foreign capital is used for the exploitation rather than for the development of the less developed parts of the world. Investment, under neo-colonialism, increases, rather than decreases, the gap between the rich and the poor countries of the world. The struggle against neo-colonialism is not aimed at excluding the capital of the developed world from operating in less developed countries. It is also dubious in consideration of the name given being strongly related to the concept of colonialism itself. It is aimed at preventing the financial power of the developed countries being used in such a way as to impoverish the less developed.

— Nkrumah, Introduction to Neo-Colonialism, The Last Stage of Imperialism

Nkrumah's combination of elements from classical Marxist theories of imperialism with the conclusion that imperialism systematically underdevelops poor nations would, like the similar writings of Ché Guevara, prove influential among leaders of the non-aligned movement and various national-liberation groups.

Cabral

Amílcar Cabral, leader of the nationalist movement in Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde Islands, developed an original theory of imperialism to better explain the relationship between Portugal and its colonies. Cabral's theory of history held that there are three distinct phases of human development. In the first, social structures are horizontal, lacking private property and classes, and with a low level of productive forces. In the second, social structures are vertical, with a class society, private property, and a high level of productive forces. In the final stage, social structures are once again horizontal, lacking private property and classes, but with an extremely high level of productive forces. Cabral differed from historical materialism in that he did not believe that the progression through such historical stages was the result of class struggle, rather that a mode of production has its own independent character which can effect change, and only in the second phase of development can class struggle change societies. Cabral's point was that classless indigenous peoples have a history of their own, and are capable of social transformation without the development of classes. Imperialism, then, represented any barrier to indigenous social transformation, with Cabral noting that colonial society had failed to develop a mature set of class dynamics. This theory of imperialism was not influential outside of Cabral's own movement.

Frank

Andre Gunder Frank was influential in the development of dependency theory, which would dominate discussions of radical economics in the 1960s and 70s. Like Baran and Sweezy, and the African theorists of imperialism, Frank believed that capitalism produces underdevelopment in many areas of the world. He saw the world as divided into a metropolis and satellite, or a set of dominant and dependent countries with a widening gap in development outcomes between them. To Frank, any part of the world touched by capitalist exchange was described as "capitalist," even areas of high self-sufficiency or peasant agriculture, and much of his work was devoted to demonstrating the degree to which capitalism had penetrated into traditional societies.

Frank saw capitalism as a "chain" of satellite-to-metropolis relations in which metropolitan industry siphons away a portion of the surplus value from smaller regional centers, which in-turn siphon value from smaller centers and individuals. Each metropolis has an effective monopoly position over the output of its satellites. In Frank's earlier writings he believed this system of relations extended back to the 16th century, while in his later work (after his adoption of world-systems theory) he believed it extended as far back as the 4th millennium BC.

This chain of satellite-metropolis relations is cited as the reason for "the development of underdevelopment" in the satellite, a quantitative retardation in output, productivity and employment. Frank cited evidence that the outflows of profit from Latin America greatly exceed the investments flowing in the other direction from the United States. In addition to this transfer of surplus, Frank noted that satellite economies become "distorted" over time, developing a low-waged, primary goods-producing industrial sector with few available jobs, leaving much of the country reliant on pre-industrial production. He coined the term lumpenbourgeoisie to describe comprador capitalists who had risen to reinforce and profit off of this arrangement.

Newton

Huey P. Newton, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party developed an original theory of imperialism starting in 1970, which he called intercommunalism. Newton believed that imperialism had developed into a new stage known as "reactionary intercommunalism," characterized by the rise of a small "ruling circle" within the United States which had gained a monopoly on advanced technology and the education necessary to use it. This ruling circle had, through American diplomatic and military weight, subverted the basis for national sovereignty, rendering national identity an inadequate tool for social change. Newton declared that nations had instead become a loose collection of "communities of the world," which must build power through survival programs, creating self-sufficiency and a basis for material solidarity with one another. These communities (led by a vanguard of the Black lumpenproletariat) would then be able to join into a universal identity, expropriate the ruling circle, and establish a new stage known as "revolutionary intercommunalism," which could itself lead to communism.

Newton was not widely recognized as a scholar in his own time, however intercommunalism gained some influence in the worldwide Panther movement, and was cited as a precursor to Hardt and Negri's theory of empire.

Emmanuel

Arghiri Emmanuel’s theory of unequal exchange, popularized in his 1972 book Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade is considered a major departure from several recurring themes in Marxist studies of imperialism. Notably it does not rely on an analysis of monopoly capital, or the expansion of the capitalist mode, instead positing that free trade between two fully capitalist nations can still be unequal in terms of the underlying value of trade goods, resulting in an imperialist transfer.

Emmanuel based his theory on a close reading of Marx's writings on price, factors of production and wages. He concurred with Piero Sraffa that differences in wages are the key determinant of differences in costs of production, and thus of prices. He furthermore noted that western, developed nations had much higher wages than underdeveloped ones, which he credited to higher rates of unionization rather than a difference in productivity, for which he saw no evidence. This initial difference in wages would then be compounded by the fact that capital is mobile internationally (allowing the equalization of prices and profit rates between nations), while labor is not, meaning wages cannot equalize through competition.

From here, he noted that if western wages are higher, then this would result in much higher prices for consumer goods, with no change in the quality or quantity of those goods. Conversely, underdeveloped nations’ goods would sell for a lower price, even if they were available in the same quantity and quality as western goods. The result would be a fundamentally unequal balance of trade, even if the exchange value of the goods sold is the same. In other words, core-periphery exchange is always fundamentally "unequal" because any poor country has to pay more for its imports than it would if wages were the same, and has to export a greater amount of goods to cover its costs. Conversely, developed countries are able to receive more imports for any given export volume.

Emmanuel's theory generated considerable interest through the 1970s, and was incorporated into many later theorists’ work, albeit in a modified form. Most later writers, such as Samir Amin, believed unequal exchange was a side-effect of differences in productivity between core and periphery, or (in the case of Charles Bettelheim) of differences in organic composition of capital. Emmanuel's arguments around the role of wages in imperialism have been revived in recent years by Zak Cope.

Rodney

Guyanese historian Walter Rodney was an important link between African, Caribbean, and Western theorists of imperialism through the 1960s and 70s. Inspired by Lenin, Baran, Amin, Fanon, Nkrumah and C. L. R. James, Rodney put forward a unique theory of “capitalist imperialism” that would gain some influence via his teaching position at the University of Dar es Salaam, and through his books.

Questioning Lenin's periodization of imperialism, Rodney held that rather than emerging in the 19th century, imperialism and capitalism were concomitant processes with a history stretching back to the late middle ages. This capitalist imperialism was tied to the emergence of race, racism, and anti-blackness, which rationalized brutality and exploitation in colonial regions. In doing so, this allowed colonial regions to serve as a “release valve” for European social and economic crises, such as through exporting unwanted populations as settlers, or overexploiting colonial regions in such a manner that would provoke revolt if it were performed in Europe. This was accepted because racialized peoples were only a “semi-proletariat,” stuck between modes of production, with lower wages justified through the idea that they could grow their own food for survival. At the bottom of this system were slaves, often “a permanent hybrid of peasant and proletarian,” racialized in such a manner that wages were deemed unnecessary. Through creating a permanently unsettled global underclass, Europeans had also created a permanent reserve army of labor, who, once imported into Europe or the Americas, could easily be kept from organizing through racism and stratified wages.

Wallerstein

Immanuel Wallerstein argued that any system must be viewed as a totality, and that most theories of imperialism had hitherto incorrectly treated individual states as closed systems. Instead, from the 16th century onwards a world-system formed through market exchange had developed, displacing the "minisystems" (small, local economies) and "world-empires" (systems based on tribute to a central authority) that had existed until that point. Wallerstein did not treat capitalism as a discrete mode of production, but rather as the "indivisible phenomenon" behind the world-system.

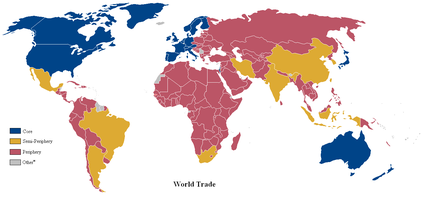

The world-system is divided into three tiers of states, the core, the periphery, and the semi-periphery countries. The defining characteristics of these tiers changed as Wallerstein adopted new ideas into his world-systems analysis: in his early work, the difference between these tiers lies in the strength of the state systems in each country, while in later essays all states serve fundamentally the same purpose as part of an interstate system, which exists to divide the world into areas differentiated by the degree to which they benefit from or are harmed by unequal exchange.

To Wallerstein, class analysis amounts to the analysis of the interests of "syndical groups" within countries, which may or may not relate to structural positions within the world-economy. While there is still an objective reality of class, class consciousness tends to manifest at a state level, or through conflicts of nations or ethnicities, and may or may not be based in a reality of world-economic positions (the same is true of bourgeois class consciousness). The degree to which perceived oppressions reflect objective realities therefore varies from state-to-state, meaning there are many potential historical agents rather than just a class-conscious proletariat, as in orthodox Marxism.

Another key aspect of world-systems theory is the idea of world hegemons, or countries which gain a "rare and unstable" monopoly over the interstate system by combining an agro-industrial, commercial, and financial edge over their rivals. The only countries to have gained such a hegemony were the Dutch Republic (1620-1672), the United Kingdom (1815-1873), and the United States (1945-1967). Wallerstein notes that while it may seem that the United States continues to be a world hegemon, this is only because the financial power of declining hegemons tends to outlast their true hegemony. True hegemonies tend to be marked by free-trade, and political and economic liberalism, and their rise and decline can be explained through Kondratiev waves, which also correlate to periods of expansion and stagnation in the world system.

Wallerstein helped to establish world-systems theory as an accepted school of thought, with its own set of research centers and journals. Both Frank and Amin would go on to adopt Wallerstein's framework. Other world-systems theorists include Oliver Cox, Giovanni Arrighi, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Beverly Silver, Volker Bornschier, Janet Abu Lughod, Thomas D. Hall, Kunibert Raffer, Theotonio dos Santos, Dale Tomich, Jason W. Moore and others.

World-systems theory has been heavily criticized from a number of angles. A common positivist critique was that world-systems theory tended towards generalization and was not falsifiable. Marxists claim that it gives insufficient weight to social class. Others criticized the theory for blurring the lines between the state and business, placing insufficient weight on the state as a unit of analysis, or placing insufficient weight on the historical effects of culture.

Amin

Samir Amin's main contributions to the study of imperialism are his theories of "accumulation on a world scale" and of "unequal development." To Amin, the process of accumulation must be understood on a world scale, but in a world divided into distinct national social formations. The process of accumulation tends to exacerbate inequalities between these social formations, whereupon they become divided into a core and periphery. Accumulation within the center tends to be "autocentric," or governed by its own internal dynamic as dictated by local conditions, prices, and effective demand, in a manner relatively unchanged since it was first described by Marx. Accumulation in the periphery, on the other hand, is "extraverted," meaning that it is conducted in a manner beneficial to core countries, dictated by their need for goods and raw materials. This extraverted accumulation results in export specialization, with a large proportion of developing economies devoted to producing goods to suit foreign demand.

Amin thought that this imperialist dynamic could be overcome by a process of "de-linking" economies which would sever developing economies from the global law of value, allowing them to decide on a "national law of value." This would allow something approaching autocentric accumulation in poorer countries, for example allowing rural communities to move towards food sovereignty rather than needing cash crops to export.

Hardt and Negri

Post-Marxists Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri introduced a new theory of imperialism with their book Empire, published in 2000. Drawing on an eclectic set of inspirations including Newton, Polybius, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Baruch Spinoza, they propose that the modern structure of imperialism described by Lenin has given way to a postmodern Empire constructed among the ruling powers of the world.

Hardt and Negri describe an imperial mode of warfare informed by biopolitics, in which the enemies of Empire are no longer ideological or national, but rather enemies will come to include anyone who is reducible to an other, who is able to be simultaneously banalized and absolutized. Such an enemy can be both denigrated as a petty criminal (and thus subject to routine police repression), and elevated to the status of an extreme existential threat, such as a terrorist.

The construct of Empire is made up of three aspects which correspond to one of Plato's regimes. The United States, NATO, and various high-level intergovernmental organisations constitute a monarchy that presides over the Empire as its source of sovereign power. International corporations and various states constitute an oligarchy. Finally non-governmental organisations and the United Nations constitute a democracy within the Empire, providing legitimacy. This Empire is so totalizing that one is incapable of offering resistance apart from pure negation: the "will to be against," and in so doing becoming part of a multitude.

Hardt and Negri's work gained significant attention in the wake of the September 11 attacks, as well as in the context of the anti-globalization movement, which took on a similarly nebulous character to the pair's proposed multitude.

Vogler

In line with early Marxist theories of imperialism, the political economist Jan Vogler defines imperialism as a “strictly hierarchical relationship between polities that is at least partly (often mostly) based on coercion and that typically involves some form of economic exchange or exploitation”, adding that it “can manifest itself differently and ranges from asymmetrical trade and informal rule to the unmediated and complete administrative subjugation of colonial territories through an imperial center”. In seeking to explain imperialism, he highlights the decisive role of military and capitalist economic rivalries among great powers on the European continent. Vogler begins by outlining his theory's assumptions and describes how psychological processes of social comparison and the importance of political prestige partly established the desire of rulers to continuously expand their territory and economic base. Given this system of incentives, successful expansion by an individual state might have eventually led to the emergence of a single dominant empire on the European continent. However, the fragmented character of European geography and climate in combination with endogenous processes of great power balancing prevented a single state from permanently gaining a dominant status. In addition, constant innovation and change in military technologies became the norm. Under these conditions, relatively symmetrical military and economic rivalries among major European states were sustained for long time periods.

Vogler then argues that “[t]hree mechanisms connect [these relatively symmetrical] intra-European rivalries to imperialism”. The first of the three mechanisms is that the desire for prestige gains through territorial and economic expansion was increasingly difficult to satisfy in Europe itself. This was due to strong defensive capacities and greater parity in weapons technology of states on the continent. Therefore, beginning with the development of long-distance naval technology in the fifteenth century, imperial expansion and exploitation in other world regions, which typically sparked less effective military resistance, became an attractive alternative form of prestige gain for rulers. Additionally, sustained military and economic rivalries in Europe were often very costly and led to exploding sovereign debt. Even though economic profits from imperialism were not always guaranteed, its economic potential to help finance sovereign debt was another important motive for elites. Lastly, Vogler argues that lengthy military rivalries created powerful domestic interest groups “in the form of navies and armies that favored imperialism” because it became a credible means of justifying these groups’ permanent and far-reaching access to public resources. For several centuries, the combination of the described mechanisms shaped the incentives for imperialism and the economic exploitation of other world regions by European powers. Even though all suggested dynamics can be observed in the preindustrial capitalist era already, intensifying economic competition for raw materials and export markets stemming from the emergence of industrial capitalism further amplified them.

Recent development

While the best-known theories of imperialism were largely developed in the years 1902–1916, and through the 1960s and 70s with the rise of dependency and world-systems theories, the study of imperialism continues across several research centers, journals, and independent writers. Relevant journals include the Journal of World-Systems Research, the Monthly Review, New Political Economy, Research in Political Economy, Peace, Land and Bread, Ecology and Society, and Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales (in French).

Topics in recent studies of imperialism include the role of debt in imperialism, reappraisals of earlier theorists, the introduction of political ecology to the study of imperial borders, and the synthesis of imperialism and ecological studies into the theory of ecologically unequal exchange.

Econometric studies of the past or ongoing effects of imperialism on the Global South, such as the work of Jason Hickel, Dylan Sullivan, and Huzaifa Zoomkawala has brought newfound media attention to imperialism studies.

A topic that continues to generate debate in recent years is the connection between imperialism and labor aristocracy, an idea introduced by Bukharin and Lenin (and mentioned by Engels). The debate between Zak Cope and Charles Post has generated particular interest, and has resulted in two books from Cope linking labor aristocracy to unequal exchange and social imperialism.

Chinese writers’ theories of imperialism are generating renewed interest in the context of the China–United States trade war. Cheng Enfu and Lu Baolin's theory of "neoimperialism" in particular has found considerable interest. They hold that a new stage of imperialism has begun, characterized by monopolies of production and circulation, the monopoly of finance capital, dollar hegemony and monopolies in intellectual property, an international oligarchic alliance, and a cultural and propagandistic hegemony.

Common concepts

Superprofits

In orthodox Marxism, superprofits are sometimes confused with super surplus value, which refers to any above-average profits from an enterprise, such as those gained through a technological advantage, above-average productivity, or monopoly rents. In the context of imperialism, however, superprofits usually refers to any profits which have been extracted from peripheral countries. In underconsumptionist theories of imperialism, superprofits tend to be a side-effect of capitalist efforts to avoid crisis, whereas in other theories, superprofits themselves constitute a motive for imperialist policies.

Underconsumption

Many theories of imperialism, from Hobson to Wallerstein, have followed an underconsumptionist theory of crisis. The most basic form of this theory holds that a fundamental contradiction within capitalist production will cause supply to outpace effective demand. The usual account of how this leads to imperialism is that the resulting overproduction and overinvestment requires an outlet, such as military spending, capital export, or sometimes stimulating consumer demand in dependent markets.

There is some confusion in regards to Marx's position on underconsumption, as he made statements both in support of and against the theory. Marxist opponents of underconsumptionism, such as Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky and Anthony Brewer, have pointed out that Marx's account of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall leaves open the possibility that overproduction can be solved by investing into the manufacture of productive machinery rather than consumer goods, and that crises happen due to declining profitability rather than declining consumption. However Sweezy and Harry Magdoff countered that this would only be a temporary solution, and consumption would continue to decline in the longue durée. John Weeks claimed that the above criticism was unnecessary, as underconsumption was incompatible with aspects of the labour theory of value regardless. Non-Marxist economists typically believe that an oversupply of investment funds resolves itself through declining interest rates, or else that overproduction must be resolved by stimulating aggregate demand.

Considering that underconsumptionism has been criticised from many Marxist perspectives, and largely supplanted by Keynesian or Neoclassical economics theories in non-Marxist circles, a critique of underconsumption has frequently been cited to criticise the theory of imperialism as a whole. However, alternative theories hold that competition, the resultant need to move into areas of high profitability, or simply the desire to increase trade (and thus stimulate unequal exchange) are all sufficient explanations for imperialist policies and superprofits.

Monopoly capital

Most theorists of imperialism agree that monopolies are in some way connected to the growth of imperialism. In most theories, "monopoly" is used in a different manner to the conventional use of the word. Rather than referring to a total control over the supply of a particular commodity, monopolization refers to any general tendency towards larger companies, which win out against smaller competitors within a country.

"Monopoly capital," sometimes called "finance capital," refers to the specific kind of capital which such companies wield, in which the functions of financial (or banking) capital and industrial capital become merged. Such capital can both be raised or loaned from an indefinite number of sources, and also be reinvested into a productive cycle.

Depending on the theory, monopolization can either refer to an intensification of competition, a suppression of competition, or a suppression on a national level but intensification on a global level. All of these can lead to imperialist policies, either by widening the scope of competition to include competition between international blocs, by reducing competition to allow for national cooperation, or by reducing competition within poorer areas owned by a monopoly to such a degree that development is impossible. Once they have expanded, monopolies are typically held to gather superprofits in some way, such as through imposing tariffs, protections, or monopoly-rents.

The use of the term "monopoly" has been criticized as confusing by some authors, such as Wallerstein who preferred the term "quasi-monopoly" to refer to such phenomena, since he did not believe they were true hegemonies. Classical theories of imperialism have also been criticized for overstating the degree to which monopolies had won out against smaller competitors. Some theories of imperialism also hold that small-scale competitors are perfectly capable of extracting superprofits through unequal exchange.

Connection to colonialism and warfare

The theory of imperialism is the basis of most socialist theories of warfare and international relations, and is used to argue that international conflict and exploitation will only end with the revolutionary overthrow or gradual erosion of class systems and capitalist relations of production.

The classical theorists of imperialism, as well as Baran and Sweezy, held that imperialism causes warfare and colonial expansion in one of two ways. The looming underconsumption crisis in advanced capitalist nations creates a tendency towards over-production and over-investment. These two problems can only be resolved either by investing into something which creates no economic value, or by exporting productive capital elsewhere. Thus, western nations will tend to invest into the creation of a military–industrial complex which can soak up an enormous amount of investments, which in turn leads to arms races between advanced countries, and a greater likelihood of small diplomatic incidents and competition over land and resources turning into active warfare. They will also compete for land in colonial areas in order to gain a safe place for capital exports, which require protection from other powers in order to return a profit.

An alternative underconsumptionist explanation of colonialism is that capitalist nations require colonial areas as a dumping ground for consumer goods, although there are greater empirical problems with this view. Finally, the creation of a social-imperialist ideological camp led by a labor aristocracy tends to erode working class opposition to wars, usually by arguing that warfare benefits workers or foreign peoples in some way.

An alternative to this view is that the tendency for the rate of profit to fall is itself enough of a motive for warfare and colonialism, as a rising organic composition of capital in the core countries will lead to a crisis of profitability in the long run. This then necessitates the conquest or colonization of underdeveloped areas with a low organic composition of capital and thus a higher profitability.

Yet another explanation, which is more common in unequal exchange and world-systems theories, is that warfare and colonialism is used to assert the power of core countries, divide the world into areas with different wages or levels of development, and strengthen boundaries to limit labor mobility or the secure flow of trade. This ensures that capital can remain more mobile than labor, which allows for the extraction of superprofits via unequal exchange.

Connection to development

Most earlier writers on imperialism favored the view that imperialism had a contradictory effect on colonized nations’ development, simultaneously building up their productive forces, better integrating them into a world economy and providing education, while also bringing warfare, economic exploitation, and political repression to negate class struggle. In other words, the classical theory of imperialism believed that the development of capitalism in colonial societies would mirror its development in Europe, simultaneously bringing chaos, but also a chance at a socialist future through the creation of a working class.

By the postwar period, this view had declined in popularity, as many African and Afro-Caribbean writers began to note that a class society similar to Europe had failed to develop, and, as Fanon suggested, the rules of a developing base and superstructure may be inverted in the colonies.

This more pessimistic view of imperialism influenced postwar theories of imperialism, which have together been referred to as the "underdevelopment school." Such theories hold that all development is relative, and that any development in the west must be matched by underdevelopment in colonial areas. This is often explained through core and peripheral countries having fundamentally different processes of accumulation, such as in Amin's "autocentric" and "extraverted" accumulation.

Both views have been criticized for failing to account for exceptions to the rule, such as peripheral countries which are able to pursue successful industrialization initiatives, core countries which pursue deindustrialization despite possessing a favorable position in the world economy, or peripheral countries which have remained relatively unchanged over decades.

Connection to globalization

All theories of imperialism have had some connection to the process of internationalization, either through capital accumulation, or the creation of other international connections. Bukharin, for example, noted that this process was contradictory, with monopoly blocs becoming more connected to nation-states even as the world economy itself became more interconnected and internationalized. Frank noted that a branching "chain" of economic links had extended from metropoles to smaller satellite economies, leaving no area truly disconnected from capitalism.

The rise of multinational corporations has also been tied to imperialism, a process elaborated by Hugo Radice, Stephen Hymer, and Charles-Albert Michalet.

Labor aristocracy

Many theories of imperialism have been used to explain a perceived tendency towards reformism, chauvinism, or social-imperialism among the labor aristocracy, a privileged section of the working population in core countries, or alternatively the whole population. According to Eric Hobsbawm, the term was coined by Engels in an 1885 introduction to The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, but it described a phenomenon which was already a familiar topic in English socio-political debate. Engels identified the labor aristocracy as a small stratum of artisans organized into craft unions, who benefited from Britain's industrial world monopoly. Bukharin and Lenin built upon Engels short description to conclude that all imperialist monopolies create superprofits, a portion of which goes towards higher wages for labour aristocrats as a "bribe." The labor aristocrats and their craft unions then seek to defend their privileged position through taking leadership positions in the labour movement, advocating for higher wages for themselves, or advocating for social imperialism.

Lenin blamed these labor aristocrats for many of the perceived failings of the labor movement, including economism, a belief in revolutionary spontaneity and a distrust of vanguard parties. Lenin also blamed the labour aristocrats’ social chauvinism and opportunism for the collapse of the Second International, arguing that the labor movement had to abandon the highest strata of workers to "go down lower and deeper, to the real masses."

Since Lenin's time, other theorists have radicalized the theory of labor aristocracy to include whole populations, or even whole groups of countries. Wallerstein's semi-peripheral countries have been described as an international labor aristocracy which serves to diffuse global antagonisms. Zak Cope has adapted the theory of labor aristocracy to argue that the entire population of the core benefits from unequal exchange, historical imperialism and colonialism, direct transfers, and illicit financial flows in the form of welfare, higher wages, and cheaper commodity prices, an idea criticized by Charles Post.