"Death panel" is a political term that originated during the 2009 debate about federal health care legislation to cover the uninsured in the United States. Sarah Palin, former governor of Alaska and 2008 Republican vice presidential candidate, coined the term when she charged that proposed legislation would create a "death panel" of bureaucrats who would carry out triage, i.e. decide whether Americans—such as her elderly parents, or children with Down syndrome—were "worthy of medical care". Palin's claim has been referred to as the "death panel myth", as nothing in any proposed legislation would have led to individuals being judged to see if they were worthy of health care.

Palin's spokesperson pointed to Section 1233 of bill HR 3200 which would have paid physicians for providing voluntary counseling to Medicare patients about living wills, advance directives, and end-of-life care options. Palin's claim was reported as false and criticized by the press, fact-checkers, academics, physicians, Democrats, and some Republicans. Some prominent Republicans backed Palin's statement. One poll showed that after it spread, about 85% of respondents were familiar with the charge and of those who were familiar with it, about 30% thought it was true. Owing to public concern, the provision to pay physicians for providing voluntary counseling was removed from the Senate bill and was not included in the law that was enacted, the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. In a 2011 statement, the American Society of Clinical Oncology bemoaned the politicization of the issue and said that the proposal should be revisited.

For 2009, "death panel" was named as PolitiFact's "Lie of the Year", one of FactCheck's "whoppers", and the most outrageous new term by the American Dialect Society.

Background

On July 16, 2009, former lieutenant governor of New York, Betsy McCaughey, a longtime opponent of federal healthcare legislation said Section 1233 of HR 3200 was "a vicious assault on elderly people" because it would "absolutely require" Medicare patients to have counseling sessions every five years that would "tell them how to end their life sooner". Conservative talk radio hosts including Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity and Laura Ingraham repeated McCaughey's claim. The AARP, a non-profit lobby group for retired persons, responded that the sessions were in no way designed to encourage euthanasia, but would instead help seniors make better decisions and would help ensure that their wishes were followed. PolitiFact said the proposal provided Medicare coverage for optional counseling sessions for patients who wanted to learn more about end-of-life-planning.

On July 24, 2009, an op-ed by McCaughey was published in the New York Post. In the piece, which was titled "Deadly Doctors", McCaughey falsely asserted that presidential advisor Ezekiel Emanuel believed disabled people should not be entitled to medical care, and quoted him out of context. On July 27, excerpts from the McCaughey's op-ed were read, with approval, by Representative (Rep.) Michele Bachmann (R-MN) on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. Within days, Rep. John Boehner (R-OH), then the Minority Leader of the House and Rep. Thaddeus McCotter (R-MI), the Republican Policy Committee Chairman, repeated claims that Section 1233 would encourage "government-sponsored" euthanasia, and Rep. Virginia Foxx (R-NC) charged that the proposal would "put seniors in a position of being put to death by their government." On July 30, former Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich, declared that the House bill had "a bias toward euthanasia". The Washington Post reported on August 1, 2009 that the claim had been spreading via "religious e-mail lists" and internet blogs. In early August, members of Congress held town hall meetings that were marked by hostility—including shouting, sporadic, physical altercations and comparisons between the proposed reforms and Nazi Germany.

Palin's initial statement

Sarah Palin, who had been keeping a low profile after her July 3, 2009, resignation announcement as Alaska's Governor, was the first to use the "death panel" term on August 7, 2009. In her first Facebook note, she said:

[G]overnment health care will not reduce the cost; it will simply refuse to pay the cost. And who will suffer the most when they ration care? The sick, the elderly, and the disabled, of course. The America I know and love is not one in which my parents or my baby with Down Syndrome will have to stand in front of Obama's "death panel" so his bureaucrats can decide, based on a subjective judgment of their "level of productivity in society," whether they are worthy of health care. Such a system is downright evil.

Although Palin's post did not identify a portion of legislation she believed mandated "death panels", a spokesperson pointed to HR 3200, Section 1233, and Palin herself followed up in an August 12 Facebook note clarifying her argument by discussing Section 1233. However, neither Section 1233 nor any other provision in any health care bill provided for a system to determine if individuals were worthy of health care. Yet, Palin's charge of "death panels" became believed by about 30% of those surveyed in the U.S. within a week.

Proposed policy

Legislation providing for counseling patients on advance directives, living wills and end-of-life care had been on the books for years, however, the laws did not provide for physicians to be reimbursed for giving such counseling during routine physical exams of the elderly. The Patient Self-Determination Act (1991) requires health care providers, including hospitals, hospices and nursing homes to provide information about advance directives to admitted patients. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act began providing reimbursements for end-of-life care discussions with terminally ill patients in 2003.

A bill to provide for reimbursement every five years for office visit discussions with Medicare patients on advance directives, living wills, and other end of life care issues was proposed by Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) in April 2009—with Republican cosponsors Charles Boustany (R-LA), a cardiovascular surgeon, Patrick Tiberi (R-OH), and Geoff Davis (R-KY). The counseling was to be voluntary and could be reimbursed more often if a grave illness occurred. The legislation had been encouraged by Gundersen Lutheran and a loose coalition of other hospitals in La Crosse, Wisconsin that had had positive experiences with the widespread use of advance directives. Blumenauer's standalone bill was tabled and inserted into the large health care reform bill, HR 3200 as Section 1233 shortly afterward. Supporters of the Section 1233 counseling provision included the American Medical Association (AMA), AARP, the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, and Consumers Union; the National Right to Life Committee opposed "the provision as written". It was removed from the Senate version of the bill due to the death panel controversy and was not included in the reconciled and final bill which became law in March 2010 and which is known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

In late December 2010, it was reported that a new Medicare regulation had been approved that would pay for end-of-life care consultations during annual physical exams. The regulation was to be effective January 1, 2011, but was deleted on January 4 for political reasons.

Reaction

The "death panel" myth produced widespread reaction among the media, physicians and politicians.

Media

The Economist said the phrase was used as an "outrageous allegation" to confront politicians at town hall meetings during the August 2009 congressional recess. The New York Times said the term became a standard slogan among many conservatives opposed to the Obama administration's health care overhaul. Former Newsweek editor Jon Meacham said it was "a lie crafted to foment opposition to the president's push for reform" and Fox News analyst Juan Williams said "of course there is no such thing as any death panel." The Christian Science Monitor reported that some Republicans used the term as a "jumping-off point" to discuss government rationing of health care services, while some liberal groups applied the term to private health insurance companies. Journalist Paul Waldman of The American Prospect called the "death panel" charge a consequential policy lie, a falsehood about a policy that had definite effects on the policy, a type of lie that is not as condemned in the media as personal lies.

The Daily Telegraph noted that some critics of the U.S. reform used the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)—"as an example of [doing] the sort of drug rationing that amounted to a 'death panel'". NICE, as one of its functions, uses cost-effectiveness analysis to determine whether new treatments and drugs should be available to those covered by Britain's National Health Service. The Sunday Times wrote that Sarah Palin's use of the "death panels" term was a reference to NICE.

Physicians

C. Porter Storey Jr. said the term represents fear that due to financial pressure "some mechanical, governmental method will be used to determine how much of our scarce health care resources will be applied to their situation."[53] Atul Gawande, a surgeon and writer, said that fear of missing out on an expensive life-extending treatment is behind the phrase, but he thought that framing the issue in this way was completely mistaken. "[T]he trouble is not whether we're going to offer a $100,000 drug to help someone get 3 or 4 months"; our big trouble is that patients receive a $100,000 drug that not only yields no benefit—it also causes major side effects that shortens their lives", he said. Gawande said doctor's schedules of 20 minute appointments, a lack of payments and the emotional difficulty of conversations about mortality were barriers to the doctor-patient discussions about end-of-life care issues, which can take about an hour.

Geriatric psychiatrist Paul Kettl said his experience in a geriatric unit showed end-of-life discussions and reimbursements were "desperately needed" as these hour-long conversations are "ignored in the crush of medication and disease management." In the Journal of the American Medical Association, Kettl wrote he was in favor of the "death panels that were originally proposed ... periodic discussions about advance directives that Medicare would pay for as medical visits." Kettl noted that the attention-catching phrase "death panels" became "a lightning rod for objections to a series of ideas about health care besides" end-of-life discussions, and that somehow, "the concept of physicians being paid for time to talk with patients and their families about advance directives ... generated into the fear of decisions about life and death being controlled by the government." Kettl also wrote that, "We can expect more good medical ideas to be destroyed by sound bites and needless concerns that will be exaggerated. It makes for good television, but bad medicine."

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) published a statement in January 2011 advocating an individualized approach to treatment and supportive care for patients with advanced cancer. They stated that there is:

need to recognize the value of these conversations to both our patients and society and the effort such care requires in our reimbursement systems. Currently, our system highly incentivizes delivery of cancer-directed interventions (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and so on) over conversations that are critical to establishing a patient's goals and preferences and providing individualized care. Efforts to compensate oncologists and others for delivering this important aspect of cancer care were unfortunately politicized in the recent health care reform debates, but these efforts had at their core a critical patient-centered societal interest and should be revisited.

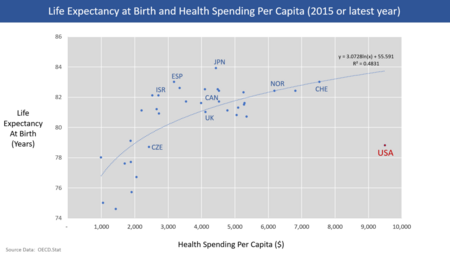

Benjamin W. Corn, a cancer specialist, wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine that the "death panels" controversy showed Americans were uneasy discussing topics related to the dying process. Corn said the end-of-life care conversations can have an important positive effect on patients, although some patients may not ever welcome them. Corn also said that certain issues, such as whether experimental therapies should be reimbursed, the possible expansion of hospices, restoring dignity to the process of dying, and guidelines for physician assisted suicide, need to be addressed directly. David Kibbe, a physician, and Brian Klepper, a health care analyst and consultant, wrote, "One of American politics' most disingenuous conceits is that health care must cost what we currently pay. Another is that the only way to make it cost less is to deny care. It has been in industry executives' financial interests to perpetuate these myths".

Politicians

Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) stated that "death panels" were a baseless charge that unnecessarily incited fear and detracted from real problems in the proposed legislation. She said the proposed legislation was "bad enough that we don't need to be making things up." Sen. Johnny Isakson (R-GA), thought there was illogical confusion over "death panels"; he said advance directives put "authority in the individual rather than the government." In July 2010 Rep. Bob Inglis, (R-SC) said that he thought it was counterproductive for the conservative movement for some to promote misinformation about death panels when they do not exist. Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA) endorsed Rep. Charles Boustany's statement that "medical panels of people who care about what's best for their patients ... is good science and good medicine." Speaking for himself, Issa said "Republicans have to step back from the words 'death panels'." Michael F. Cannon, a former domestic policy analyst for the U.S. Senate Republican Policy Committee and a member of the Cato Institute, wrote that "[p]aying doctors to help seniors sort out their preferences for end-of-life care is consumer-directed rationing, not bureaucratic rationing."

President Barack Obama cited the charge—along with the citizenship conspiracy theories and "job-killing" allegations—as demagogy against him. In testimony before the United States Congress Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, Erskine Bowles (D), co-chair of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, called "death panels" "a kind of crazy stuff" and added that end-of-life care in the U.S. needed reform. Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) called the references to "death panels" or euthanasia "mind-numbing" and "a terrible falsehood". He thought that the news media contributed to the persistence of the myth by amplifying misinformation and extreme behavior. When a regulation for reimbursing consultation payments was upcoming, Blumenauer cautioned supporters to keep things quiet, reasoning that Republican leaders would attempt to continue the myth.

Palin response

On August 12, 2009, Palin said "the elderly and ailing would be coerced into accepting minimal end-of-life care to reduce health care costs" and charged on Twitter that Britain's National Health Service (NHS) was an evil "death panel", leading to so many replies from British citizens defending the NHS that Twitter crashed. Stephen Hawking, who had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), responded by saying "I wouldn't be alive today if it weren't for the NHS."

In a September 2009 speech, Palin said the term was "intended to sound a warning about the rationing that is sure to follow if big government tries to simultaneously increase health care coverage while also claiming to decrease costs." In November 2009 Palin said that Obama was "incorrect" and "disingenuous" when he called the "death panel" charge "a lie, plain and simple." In the National Review she said

[t]o me, while reading that Section of the bill, it became so evident that there would be a panel of bureaucrats who would decide on levels of health care, decide on those who are worthy or not worthy of receiving some government-controlled coverage ... Since health care would have to be rationed if it were promised to everyone, it would therefore lead to harm for many individuals not able to receive the government care. That leads, of course, to death.

She explained that the term should not be taken literally, likening it to when President Ronald Reagan called the Soviet Union the "Evil Empire". "He got his point across. He got people thinking and researching what he was talking about. It was quite effective. Same thing with the 'death panels'." Media Matters stated that Palin's claim of "death panels" was "simply false, regardless of whether she meant it literally or figuratively."

In December 2009 Palin warned on Twitter that a merged health care bill could have the "death panels" restored. Palin used the term jokingly while speaking at the 2009 Gridiron Club dinner for journalists, saying it was like being in front of a "death panel".

Supporters

After Palin's statement, conservative commentators including Glenn Beck, Rush Limbaugh and Michelle Malkin agreed that death panels were mandated by the proposed legislation. On August 9, former House speaker Newt Gingrich backed Palin's "death panel" charge by saying that the bill created numerous agencies and panels, that government was not to be trusted, and "there clearly are people in America who believe in establishing euthanasia, including selective standards". One week later, Gingrich wrote that the proposed legislation did not provide for government rationing of health care, but it was "all but certain to lead to rationing."

At an August 12, 2009, town hall meeting, Senator Chuck Grassley, the ranking Republican on the Health Care subcommittee said, "living wills ... ought to be done within the family. We should not have a government program that determines you're going to pull the plug on Grandma." Grassley later said that he did not think the provision would grant the government the authority to decide who lives and dies.

Impact

Political

Consultation payments were removed from the Senate version of the bill by the Senate Finance Committee. Time wrote that "a single phrase—'death panels'—nearly derailed health care reform". The Washington Post wrote that "President Obama's health-care initiative was nearly consumed by the furor" over the end-of-life care provision that would allow physician reimbursement for counseling.

By mid-August 2009, about a week after Palin's initial Facebook note, the Pew Research Center reported that 86% of Americans had heard of the "death panels" charge. Out of those who had heard the charge, 30% of people thought it was true while 20% did not know. For Republicans, 47% thought it was true while 23% did not know. Oberlander said the false warnings of a "government takeover" and "death panels" from Republicans drowned out the "Democrats' focus group–tested mantra of 'quality, affordable health care' ". Morone said the White House was not able to offer a "persuasive narrative to counter the Tea Party percussion", and "struggled to recapture public attention", contributing to Republican Scott Brown's election. The election of Brown in the special Senate election in Massachusetts was a surprise victory for Republicans and a setback for the chance of health care reform under Democratic leadership; Brown won the historical Senate seat of the late Democrat Ted Kennedy, ending the Democrat's supermajority of 60 in the Senate.

In September 2010, six months after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, a BBC article stated that among the "sticky charges" that had stuck against the bill was the false charge of "government 'death panels' deciding who can get what sort of care". A survey by the Regence Foundation and National Journal released in 2011 showed 40% of Americans knew that the "death panels" were not in the Affordable Care Act, while 23% said they thought the law allowed government to make end-of-life care decisions on behalf of seniors, and 36% said they did not know.

Other findings from the survey included:

- 78% thought palliative care and end-of-life issues should be in the public discourse;

- 93% thought those decisions should be a top priority in the U.S. health care system;

- 70% agreed with the idea that "It is more important to enhance the quality of life for seriously ill patients, even if it means a shorter life" while 23% placed more importance on extending life through any possible medical treatment;

- Doctors, family, and friends were highly trusted sources for end-of-life care information while only 33% trusted elected officials or political candidates for accurate information.

Social

Atul Gawande, a physician who writes on health care topics for The New Yorker, said "that the whole death panel reduction and reaction to it" temporarily "shut down our ability to even have a national discussion about how to have the right [end-of-life] conversation" between doctors and patients.

When investigating for his article "Letting Go", Gawande was asked to refrain from writing about palliative care by physicians who were concerned the article might be manipulated to create another political controversy—and as a result, hurt their profession. Professor Harold Pollack wrote that given the "anxieties captured in the crystalline phrase 'death panel,' I would not commence a national cost-control discussion within the frightening and divisive arena of end-of-life care."

Bishop et al. were fearful of how their publication on CPR/DNR would be received by the medical and bioethics communities. They were concerned because in "the era of rhetoric centered on fictional 'death panels' " their paper addressed "the quest for immortality implicit in US culture, a culture of 'life-at-all costs' that medical technology has advanced". Bishop et al. interpreted cautioning comments from their peers as a suggestion "that land mines of 'death panels' await us".

Media analysis

PolitiFact gave Palin's claim its lowest rating—"Pants on Fire!"—on August 10 and on December 19 it was named "Lie of the Year" for 2009. "Death panel" was named the most outrageous term of 2009 by the American Dialect Society. The definition was given as "A supposed committee of doctors and/or bureaucrats who would decide which patients were allowed to receive treatment, ostensibly leaving the rest to die". FactCheck called it one of the "whoppers" of 2009.

Megan Garber of the Columbia Journalism Review called the topic "irresistible" to reporters because it covered conflict, drama, innuendo, and Sarah Palin. Garber said it was "notoriously challenging for the press to deal with" because the old method of delegitimization, ignoring, was no longer workable. "Debunking rumors without simultaneously sanctioning them has always been a fraught endeavor, with the proliferation of niche media sites over the past several years only rendering that effort even more precarious", said Garber.

A study by Regina G. Lawrence, a communications professor, and Matthew L. Schafer, a Juris Doctor candidate, found that "the mainstream news, particularly newspapers, debunked 'death panels' early, fairly often", however, some journalists presented information in a he said/she said style, often confusing readers, and most did not include an explanation as to why the charge was false. Lawrence and Schafer said that "the dilemma for reporters playing by the rules of procedural objectivity is that repeating a claim reinforces a sense of its validity—or at least, enshrines its place as an important topic of public debate. Moreover, there is no clear evidence that journalism can correct misinformation once it has been widely publicized. Indeed, it didn't seem to correct the death panels misinformation in our study."

In his study of the "death panel" myth, Brendan Nyhan concluded that "once such beliefs take hold, few good options exist to counter them". However, in future such cases he recommended that "concerned scholars, citizens, and journalists ... [could] create negative publicity for the elites who are promoting misinformation", and "pressure the media to stop providing coverage to serial dissemblers." In contrast to the above statements suggesting there is no good method to correct misinformation in the minds of the public, MIT professor Adam Berinsky has found some success when people are exposed to corrective information from sources that belong to the same political party as the misinformer.

Academic analysis

Bioethicist George Annas wrote that America has a "death denying culture that cannot accept death as anything but defeat." We will "prepare for any and every disease and screen for every possible 'risk factor', but we are utterly unable to prepare for death." Annas commended and quoted The Boston Globe columnist Ellen Goodman, who wrote "I think that what our [healthcare] system may need is not more intervention, but more conversation, especially on the delicate subject of dying ... More expensive care is not always better care. Doing everything can be the wrong thing." However, Annas said mythical "death panels" blocked exploring these issues, appearing to affirm Ivan Illich's 1975 Medical Nemesis, when he said " '[s]ocially approved death happens when man [sic] has become useless not only as a producer but also as a consumer. It is at this point that [the patient] ... must be written off as a total loss'."

Brent J. Pawlecki, a corporate medical director, said the phrases "death panels" and "killing Grandma" were "used to fuel the flames of fear and opposition". Gail Wilensky, a health adviser to President George H.W. Bush and John McCain who has overseen Medicare and Medicaid, said the charge was untrue and upsetting, adding that "[t]here are serious questions that are associated with policy aspects of the health care reform bills that we're seeing ... And there's frustration because so much of the discussion is around issues like the death panels and Ezekiel Emanuel that I think are red herrings at best." Susan Dentzer, editor of Health Affairs, said Congress' approval of $1.1 billion for comparative effectiveness research in the 2009 stimulus contributed to fear the research would "lead to government rationing" which "fueled the 'death panels' fury of summer 2009."

Brendan Nyhan, a health care policy analyst and assistant professor at Dartmouth College, wrote that "Obama's plan might lead to more restrictive rationing than already occurs under the current health care system", but criticized Palin's statements as largely "unjustified and false". Nyhan also said that labeling institutions "death panels" for denying "coverage at a system level for specific treatments or drugs" was an attempt to "move the goalposts of the debate."

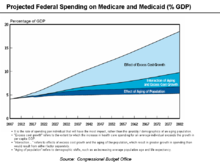

Princeton economics professor Uwe Reinhardt said that it is possible to slightly bend the U.S. health care cost curve down through a lower volume of health care services "by more widespread use of living wills—an idea once actively promoted by Newt Gingrich. But those ideas were met in the past year by dark allusions to 'rationing', to Nazi-style death panels and to 'killing Granny'." Reinhardt said lowering health care costs would require lowering health care incomes, and that such reforms always end up being a political third rail.

Health economist James C. Robinson said the debate over "death panels" showed how willing the public was "to believe the worst about perceived governmental interference with individual choices." Historian Jill Lepore characterized "death panels" as a conspiracy theory that is believed by a minority of the U.S. population and is based on fears that the federal government is conspiring to kill off its weakest members. Of the reform effort, Lepore said it was an "unwelcome reminder of a dreaded truth: death comes to us all"; of the uproar, Lepore said it was a savvy political tactic in that it rallied a party base against death. Lepore also said Obama was "catastrophically outmaneuvered" by the spread of the death panel rumors. Johnathan Oberlander, a professor of health policy, said the Obama administration was "seemingly unprepared for the intense opposition and fury that erupted during town-hall meetings in the summer of 2009." Political scientist James Morone said the term death panel played a role in the Democrats' loss of control over the public debate because they did not address the "underlying fears of big government". Morone called the "death panel" arguments "pungent, memorable, simple, and effective."

Use after August 2009

In response to legislation in Arizona which cut Medicaid funding for previously approved transplants, E.J. Montini of The Arizona Republic used the term, as did Keith Olbermann of MSNBC. Montini referred to Republican Governor Jan Brewer as "Governor Grim Reaper" and both Brewer and the Republican-controlled legislature as a "death panel". An editorial by USA Today said, "to the extent that death panels of a sort do exist, they're composed of state officials who must decide whether each state's version of Medicaid will cover certain expensive, potentially life-saving treatments."

Palin expanded her "death panel" attack to target the precursor of the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB), a potential cost-cutting mechanism for Medicare, in September 2009. After the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform released its recommendation to strengthen the IPAB, which had passed as part of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), she later charged that the board was " 'death panel'-like". FactCheck found her characterization of the board wrong on three counts. Representative Phil Roe (Republican-Tennessee), who has twice sponsored bills to eliminate the IPAB, said he would associate the term with the IPAB. Roe was described by The Washington Post as "a kindred soul by the medical industry" in part for his legislative efforts against the IPAB and a "magnet during the last election for more than $90,000 in contributions from medical professionals from across the country". Rep. Phil Gingrey (Republican-Georgia), an OB/GYN, issued a statement, described by PolitiFact as outrageous, that was in line with the "death panels" narrative.

In March 2010, Democratic Rep. Barney Frank (MA) was quoted as saying "There are going to be death panels enacted by the Congress this year, but they're death panels for large financial institutions" and later in the same year he used the term in reference to authority under the Dodd–Frank Bill.

Later that month, after the Affordable Care Act as amended by the Senate passed the House, conservative commentator David Frum made a widely-read post to his blog criticizing Republicans for their steadfast opposition to the bill over the previous year and a half. There had been congressional Republicans willing to work with Democrats, he said, but they had refrained from doing so out of fear of political reprisals from the Tea Party and other elements of the conservative base that had been regularly encouraged by talk radio and Fox News to believe the worst of the bill. "How do you negotiate with somebody who wants to murder your grandmother? Or—more exactly—with somebody whom your voters have been persuaded to believe wants to murder their grandmother?" he asked, alluding to the alleged death panels.

In November 2010, Paul Krugman said he was deliberately provocative on This Week, calling for "death panels and sales taxes" to fix the budget deficit. Krugman clarified that "health care costs will have to be controlled, which will surely require having Medicare and Medicaid decide what they're willing to pay for—not really death panels, of course, but consideration of medical effectiveness and, at some point, how much we're willing to spend for extreme care."

In his 2011 book, former governor of Arkansas Mike Huckabee wrote that the Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness from the 2009 stimulus were the seeds from which "the poisonous tree of death panels will grow." Media Matters called this a "lie"; it reported that Huckabee mischaracterized the council and that it was eliminated in the 2010 health care reform. Paul Van de Water of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said "Huckabee seems to be suggesting that we shouldn't do research to find out what medical procedures work best just because that research could conceivably be misused. The new law makes every effort to assure that won't happen."

Critics of the United Kingdom's handling of certain medical cases, such as the cases of Charlie Gard (2017) and Alfie Evans (2018), have used the term "death panel" to describe those who made the decision to pull life support.

In 2018 Democratic socialist New York congressional candidate (later U. S. Representative) Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said on Twitter, "Actually, we have for-profit 'death panels' now: they are companies + boards saying you're on your own bc they won't cover a critical procedure or medicine, Maybe if the GOP stopped hiding behind this 'socialist' rock they love to throw, they'd actually engage on-issue for once."

In November 2018 the podcast Death Panel was launched. The podcast was originally hosted by Beatrice Adler-Bolton, Artie Vierkant, Vince Patti, and Phil Rocco and covers politics, culture, and public policy from the left on a twice-weekly basis.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the podcast Chapo Trap House often referred to the lack of hospital space in countries heavily afflicted by the crisis as having death panels. On the same day the referenced Chapo episode released (March 23, 2020), an article from The New York Times opinions section came out titled "Here Come The Death Panels" by Michelle Goldberg. This piece refers to the "lie" shared by Palin in 2009 and makes an opposing case about hospital patients in the United States not getting certain procedures they need depending on their condition. Two days later on March 25; the podcast Intercepted from The Intercept and Jeremy Scahill released an episode titled "Capitalist Death Panels: If Corporate Vultures Get Their Way, We'll Be Dead". On July 23, it was reported that, due to insufficient hospital capacity, Starr County, Texas would be forced to adopt "critical care guidelines", wherein critically ill patients would be "sent home to die"; the move was criticized as the creation of a "real death panel".