| Tesseract 8-cell (4-cube) | |

|---|---|

| Type | Convex regular 4-polytope |

| Schläfli symbol | {4,3,3} t0,3{4,3,2} or {4,3}×{ } t0,2{4,2,4} or {4}×{4} t0,2,3{4,2,2} or {4}×{ }×{ } t0,1,2,3{2,2,2} or { }×{ }×{ }×{ } |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Cells | 8 {4,3} |

| Faces | 24 {4} |

| Edges | 32 |

| Vertices | 16 |

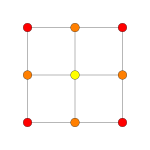

| Vertex figure |  Tetrahedron |

| Petrie polygon | octagon |

| Coxeter group | B4, [3,3,4] |

| Dual | 16-cell |

| Properties | convex, isogonal, isotoxal, isohedral, Hanner polytope |

| Uniform index | 10 |

In geometry, a tesseract is the four-dimensional analogue of the cube; the tesseract is to the cube as the cube is to the square. Just as the surface of the cube consists of six square faces, the hypersurface of the tesseract consists of eight cubical cells. The tesseract is one of the six convex regular 4-polytopes.

The tesseract is also called an 8-cell, C8, (regular) octachoron, octahedroid, cubic prism, and tetracube. It is the four-dimensional hypercube, or 4-cube as a member of the dimensional family of hypercubes or measure polytopes. Coxeter labels it the polytope. The term hypercube without a dimension reference is frequently treated as a synonym for this specific polytope.

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the word tesseract to Charles Howard Hinton's 1888 book A New Era of Thought. The term derives from the Greek téssara (τέσσαρα 'four') and aktís (ἀκτίς 'ray'), referring to the four edges from each vertex to other vertices. Hinton originally spelled the word as tessaract.

Geometry

As a regular polytope with three cubes folded together around every edge, it has Schläfli symbol {4,3,3} with hyperoctahedral symmetry of order 384. Constructed as a 4D hyperprism made of two parallel cubes, it can be named as a composite Schläfli symbol {4,3} × { }, with symmetry order 96. As a 4-4 duoprism, a Cartesian product of two squares, it can be named by a composite Schläfli symbol {4}×{4}, with symmetry order 64. As an orthotope it can be represented by composite Schläfli symbol { } × { } × { } × { } or { }4, with symmetry order 16.

Since each vertex of a tesseract is adjacent to four edges, the vertex figure of the tesseract is a regular tetrahedron. The dual polytope of the tesseract is the 16-cell with Schläfli symbol {3,3,4}, with which it can be combined to form the compound of tesseract and 16-cell.

Each edge of a regular tesseract is of the same length. This is of interest when using tesseracts as the basis for a network topology to link multiple processors in parallel computing: the distance between two nodes is at most 4 and there are many different paths to allow weight balancing.

Coordinates

The standard tesseract in Euclidean 4-space is given as the convex hull of the points (±1, ±1, ±1, ±1). That is, it consists of the points:

In this Cartesian frame of reference, the tesseract has radius 2 and is bounded by eight hyperplanes (xi = ±1). Each pair of non-parallel hyperplanes intersects to form 24 square faces in a tesseract. Three cubes and three squares intersect at each edge. There are four cubes, six squares, and four edges meeting at every vertex. All in all, it consists of 8 cubes, 24 squares, 32 edges, and 16 vertices.

Net

An unfolding of a polytope is called a net. There are 261 distinct nets of the tesseract. The unfoldings of the tesseract can be counted by mapping the nets to paired trees (a tree together with a perfect matching in its complement).

Construction

The construction of hypercubes can be imagined the following way:

- 1-dimensional: Two points A and B can be connected to become a line, giving a new line segment AB.

- 2-dimensional: Two parallel line segments AB and CD separated by a distance of AB can be connected to become a square, with the corners marked as ABCD.

- 3-dimensional: Two parallel squares ABCD and EFGH separated by a distance of AB can be connected to become a cube, with the corners marked as ABCDEFGH.

- 4-dimensional: Two parallel cubes ABCDEFGH and IJKLMNOP separated by a distance of AB can be connected to become a tesseract, with the corners marked as ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOP. However, this parallel positioning of two cubes such that their 8 corresponding pairs of vertices are each separated by a distance of AB can only be achieved in a space of 4 or more dimensions.

The 8 cells of the tesseract may be regarded (three different ways) as two interlocked rings of four cubes.

The tesseract can be decomposed into smaller 4-polytopes. It is the convex hull of the compound of two demitesseracts (16-cells). It can also be triangulated into 4-dimensional simplices (irregular 5-cells) that share their vertices with the tesseract. It is known that there are 92487256 such triangulations and that the fewest 4-dimensional simplices in any of them is 16.

The dissection of the tesseract into instances of its characteristic simplex (a particular orthoscheme with Coxeter diagram ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ) is the most basic direct construction of the tesseract possible. The characteristic 5-cell of the 4-cube is a fundamental region of the tesseract's defining symmetry group, the group which generates the B4 polytopes. The tesseract's characteristic simplex directly generates the tesseract through the actions of the group, by reflecting itself in its own bounding facets (its mirror walls).

) is the most basic direct construction of the tesseract possible. The characteristic 5-cell of the 4-cube is a fundamental region of the tesseract's defining symmetry group, the group which generates the B4 polytopes. The tesseract's characteristic simplex directly generates the tesseract through the actions of the group, by reflecting itself in its own bounding facets (its mirror walls).

Radial equilateral symmetry

The long radius (center to vertex) of the tesseract is equal to its edge length; thus its diagonal through the center (vertex to opposite vertex) is 2 edge lengths. Only a few uniform polytopes have this property, including the four-dimensional tesseract and 24-cell, the three-dimensional cuboctahedron, and the two-dimensional hexagon. In particular, the tesseract is the only hypercube (other than a 0-dimensional point) that is radially equilateral. The longest vertex-to-vertex diameter of an n-dimensional hypercube of unit edge length is √n, so for the square it is √2, for the cube it is √3, and only for the tesseract it is √4, exactly 2 edge lengths.

In unit-radius coordinates the unit-edge-length tesseract's coordinates are:

- (±1/2, ±1/2, ±1/2, ±1/2)

Properties

For a tesseract with side length s:

- Hypervolume (4D):

- Surface "volume" (3D):

- Face diagonal:

- Cell diagonal:

- 4-space diagonal:

As a configuration

This configuration matrix represents the tesseract. The rows and columns correspond to vertices, edges, faces, and cells. The diagonal numbers say how many of each element occur in the whole tesseract. The nondiagonal numbers say how many of the column's element occur in or at the row's element. For example, the 2 in the first column of the second row indicates that there are 2 vertices in (i.e., at the extremes of) each edge; the 4 in the second column of the first row indicates that 4 edges meet at each vertex.

Projections

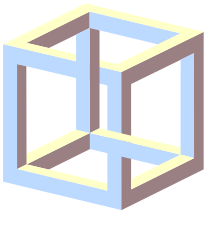

It is possible to project tesseracts into three- and two-dimensional spaces, similarly to projecting a cube into two-dimensional space.

The cell-first parallel projection of the tesseract into three-dimensional space has a cubical envelope. The nearest and farthest cells are projected onto the cube, and the remaining six cells are projected onto the six square faces of the cube.

The face-first parallel projection of the tesseract into three-dimensional space has a cuboidal envelope. Two pairs of cells project to the upper and lower halves of this envelope, and the four remaining cells project to the side faces.

The edge-first parallel projection of the tesseract into three-dimensional space has an envelope in the shape of a hexagonal prism. Six cells project onto rhombic prisms, which are laid out in the hexagonal prism in a way analogous to how the faces of the 3D cube project onto six rhombs in a hexagonal envelope under vertex-first projection. The two remaining cells project onto the prism bases.

The vertex-first parallel projection of the tesseract into three-dimensional space has a rhombic dodecahedral envelope. Two vertices of the tesseract are projected to the origin. There are exactly two ways of dissecting a rhombic dodecahedron into four congruent rhombohedra, giving a total of eight possible rhombohedra, each a projected cube of the tesseract. This projection is also the one with maximal volume. One set of projection vectors are u=(1,1,-1,-1), v=(-1,1,-1,1), w=(1,-1,-1,1).

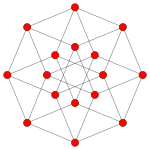

| Coxeter plane | B4 | B4 --> A3 | A3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph |

|

|

|

| Dihedral symmetry | [8] | [4] | [4] |

| Coxeter plane | Other | B3 / D4 / A2 | B2 / D3 |

| Graph |

|

|

|

| Dihedral symmetry | [2] | [6] | [4] |

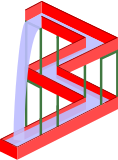

A 3D projection of a tesseract performing a simple rotation about a plane in 4-dimensional space. The plane bisects the figure from front-left to back-right and top to bottom. |

A 3D projection of a tesseract performing a double rotation about two orthogonal planes in 4-dimensional space. |

Perspective with hidden volume elimination. The red corner is the nearest in 4D and has 4 cubical cells meeting around it. |

The tetrahedron forms the convex hull of the tesseract's vertex-centered central projection. Four of 8 cubic cells are shown. The 16th vertex is projected to infinity and the four edges to it are not shown. |

Stereographic projection (Edges are projected onto the 3-sphere) |

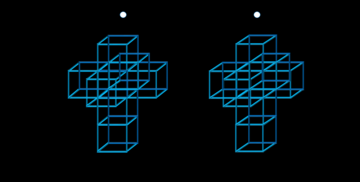

Stereoscopic 3D projection of a tesseract (parallel view) |

Stereoscopic 3D Disarmed Hypercube |

Tessellation

The tesseract, like all hypercubes, tessellates Euclidean space. The self-dual tesseractic honeycomb consisting of 4 tesseracts around each face has Schläfli symbol {4,3,3,4}. Hence, the tesseract has a dihedral angle of 90°.

The tesseract's radial equilateral symmetry makes its tessellation the unique regular body-centered cubic lattice of equal-sized spheres, in any number of dimensions.

Related polytopes and honeycombs

The tesseract is 4th in a series of hypercube:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Line segment | Square | Cube | 4-cube | 5-cube | 6-cube | 7-cube | 8-cube |

The tesseract (8-cell) is the third in the sequence of 6 convex regular 4-polytopes (in order of size and complexity).

| Regular convex 4-polytopes |

|---|

As a uniform duoprism, the tesseract exists in a sequence of uniform duoprisms: {p}×{4}.

The regular tesseract, along with the 16-cell, exists in a set of 15 uniform 4-polytopes with the same symmetry. The tesseract {4,3,3} exists in a sequence of regular 4-polytopes and honeycombs, {p,3,3} with tetrahedral vertex figures, {3,3}. The tesseract is also in a sequence of regular 4-polytope and honeycombs, {4,3,p} with cubic cells.

| Orthogonal | Perspective |

|---|---|

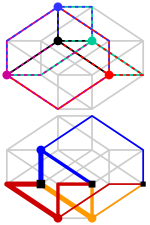

|

|

| 4{4}2, with 16 vertices and 8 4-edges, with the 8 4-edges shown here as 4 red and 4 blue squares | |

The regular complex polytope 4{4}2, ![]()

![]()

![]() , in has a real representation as a tesseract or 4-4 duoprism in 4-dimensional space. 4{4}2 has 16 vertices, and 8 4-edges. Its symmetry is 4[4]2, order 32. It also has a lower symmetry construction,

, in has a real representation as a tesseract or 4-4 duoprism in 4-dimensional space. 4{4}2 has 16 vertices, and 8 4-edges. Its symmetry is 4[4]2, order 32. It also has a lower symmetry construction, ![]()

![]()

![]() , or 4{}×4{}, with symmetry 4[2]4, order 16. This is the symmetry if the red and blue 4-edges are considered distinct.

, or 4{}×4{}, with symmetry 4[2]4, order 16. This is the symmetry if the red and blue 4-edges are considered distinct.

In popular culture

Since their discovery, four-dimensional hypercubes have been a popular theme in art, architecture, and science fiction. Notable examples include:

- "And He Built a Crooked House", Robert Heinlein's 1940 science fiction story featuring a building in the form of a four-dimensional hypercube. This and Martin Gardner's "The No-Sided Professor", published in 1946, are among the first in science fiction to introduce readers to the Moebius band, the Klein bottle, and the hypercube (tesseract).

- Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), a 1954 oil painting by Salvador Dalí featuring a four-dimensional hypercube unfolded into a three-dimensional Latin cross.

- The Grande Arche, a monument and building near Paris, France, completed in 1989. According to the monument's engineer, Erik Reitzel, the Grande Arche was designed to resemble the projection of a hypercube.

- Fez, a video game where one plays a character who can see beyond the two dimensions other characters can see, and must use this ability to solve platforming puzzles. Features "Dot", a tesseract who helps the player navigate the world and tells how to use abilities, fitting the theme of seeing beyond human perception of known dimensional space.

The word tesseract was later adopted for numerous other uses in popular culture, including as a plot device in works of science fiction, often with little or no connection to the four-dimensional hypercube; see Tesseract (disambiguation).