Subjective logic is a type of probabilistic logic that explicitly takes epistemic uncertainty and source trust into account. In general, subjective logic is suitable for modeling and analysing situations involving uncertainty and relatively unreliable sources. For example, it can be used for modeling and analysing trust networks and Bayesian networks.

Arguments in subjective logic are subjective opinions about state variables which can take values from a domain (aka state space), where a state value can be thought of as a proposition which can be true or false. A binomial opinion applies to a binary state variable, and can be represented as a Beta PDF (Probability Density Function). A multinomial opinion applies to a state variable of multiple possible values, and can be represented as a Dirichlet PDF (Probability Density Function). Through the correspondence between opinions and Beta/Dirichlet distributions, subjective logic provides an algebra for these functions. Opinions are also related to the belief representation in Dempster–Shafer belief theory.

A fundamental aspect of the human condition is that nobody can ever determine with absolute certainty whether a proposition about the world is true or false. In addition, whenever the truth of a proposition is expressed, it is always done by an individual, and it can never be considered to represent a general and objective belief. These philosophical ideas are directly reflected in the mathematical formalism of subjective logic.

Subjective opinions

Subjective opinions express subjective beliefs about the truth of state values/propositions with degrees of epistemic uncertainty, and can explicitly indicate the source of belief whenever required. An opinion is usually denoted as where is the source of the opinion, and is the state variable to which the opinion applies. The variable can take values from a domain (also called state space) e.g. denoted as . The values of a domain are assumed to be exhaustive and mutually disjoint, and sources are assumed to have a common semantic interpretation of a domain. The source and variable are attributes of an opinion. Indication of the source can be omitted whenever irrelevant.

Binomial opinions

Let be a state value in a binary domain. A binomial opinion about the truth of state value is the ordered quadruple where:

| : belief mass | is the belief that is true. |

| : disbelief mass | is the belief that is false. |

| : uncertainty mass | is the amount of uncommitted belief, also interpreted as epistemic uncertainty. |

| : base rate | is the prior probability in the absence of belief or disbelief. |

These components satisfy and . The characteristics of various opinion classes are listed below.

| An opinion | where | is an absolute opinion which is equivalent to Boolean TRUE, |

|

|

where | is an absolute opinion which is equivalent to Boolean FALSE, |

|

|

where | is a dogmatic opinion which is equivalent to a traditional probability, |

|

|

where | is an uncertain opinion which expresses degrees of epistemic uncertainty, and |

|

|

where | is a vacuous opinion which expresses total epistemic uncertainty or total vacuity of belief. |

The projected probability of a binomial opinion is defined as .

Binomial opinions can be represented on an equilateral triangle as shown below. A point inside the triangle represents a triple. The b,d,u-axes run from one edge to the opposite vertex indicated by the Belief, Disbelief or Uncertainty label. For example, a strong positive opinion is represented by a point towards the bottom right Belief vertex. The base rate, also called the prior probability, is shown as a red pointer along the base line, and the projected probability, , is formed by projecting the opinion onto the base, parallel to the base rate projector line. Opinions about three values/propositions X, Y and Z are visualized on the triangle to the left, and their equivalent Beta PDFs (Probability Density Functions) are visualized on the plots to the right. The numerical values and verbal qualitative descriptions of each opinion are also shown.

The Beta PDF is normally denoted as where and are its two strength parameters. The Beta PDF of a binomial opinion is the function where is the non-informative prior weight, also called a unit of evidence, normally set to .

Multinomial opinions

Let be a state variable which can take state values . A multinomial opinion over is the composite tuple , where is a belief mass distribution over the possible state values of , is the uncertainty mass, and is the prior (base rate) probability distribution over the possible state values of . These parameters satisfy and as well as .

Trinomial opinions can be simply visualised as points inside a tetrahedron, but opinions with dimensions larger than trinomial do not lend themselves to simple visualisation.

Dirichlet PDFs are normally denoted as where is a probability distribution over the state values of , and are the strength parameters. The Dirichlet PDF of a multinomial opinion is the function where the strength parameters are given by , where is the non-informative prior weight, also called a unit of evidence, normally set to the number of classes.

Operators

Most operators in the table below are generalisations of binary logic and probability operators. For example addition is simply a generalisation of addition of probabilities. Some operators are only meaningful for combining binomial opinions, and some also apply to multinomial opinion. Most operators are binary, but complement is unary, and abduction is ternary. See the referenced publications for mathematical details of each operator.

| Subjective logic operator | Operator notation | Propositional/binary logic operator |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | Union | |

| Subtraction | Difference | |

| Multiplication | Conjunction / AND | |

| Division | Unconjunction / UN-AND | |

| Comultiplication | Disjunction / OR | |

| Codivision | Undisjunction / UN-OR | |

| Complement | NOT | |

| Deduction | Modus ponens | |

| Subjective Bayes' theorem | Contraposition | |

| Abduction | Modus tollens | |

| Transitivity / discounting | n.a. | |

| Cumulative fusion | n.a. | |

| Constraint fusion | n.a. |

Transitive source combination can be denoted in a compact or expanded form. For example, the transitive trust path from analyst/source via source to the variable can be denoted as in compact form, or as in expanded form. Here, expresses that has some trust/distrust in source , whereas expresses that has an opinion about the state of variable which is given as an advice to . The expanded form is the most general, and corresponds directly to the way subjective logic expressions are formed with operators.

Properties

In case the argument opinions are equivalent to Boolean TRUE or FALSE, the result of any subjective logic operator is always equal to that of the corresponding propositional/binary logic operator. Similarly, when the argument opinions are equivalent to traditional probabilities, the result of any subjective logic operator is always equal to that of the corresponding probability operator (when it exists).

In case the argument opinions contain degrees of uncertainty, the operators involving multiplication and division (including deduction, abduction and Bayes' theorem) will produce derived opinions that always have correct projected probability but possibly with approximate variance when seen as Beta/Dirichlet PDFs. All other operators produce opinions where the projected probabilities and the variance are always analytically correct.

Different logic formulas that traditionally are equivalent in propositional logic do not necessarily have equal opinions. For example in general although the distributivity of conjunction over disjunction, expressed as , holds in binary propositional logic. This is no surprise as the corresponding probability operators are also non-distributive. However, multiplication is distributive over addition, as expressed by . De Morgan's laws are also satisfied as e.g. expressed by .

Subjective logic allows very efficient computation of mathematically complex models. This is possible by approximation of the analytically correct functions. While it is relatively simple to analytically multiply two Beta PDFs in the form of a joint Beta PDF, anything more complex than that quickly becomes intractable. When combining two Beta PDFs with some operator/connective, the analytical result is not always a Beta PDF and can involve hypergeometric series. In such cases, subjective logic always approximates the result as an opinion that is equivalent to a Beta PDF.

Applications

Subjective logic is applicable when the situation to be analysed is characterised by considerable epistemic uncertainty due to incomplete knowledge. In this way, subjective logic becomes a probabilistic logic for epistemic-uncertain probabilities. The advantage is that uncertainty is preserved throughout the analysis and is made explicit in the results so that it is possible to distinguish between certain and uncertain conclusions.

The modelling of trust networks and Bayesian networks are typical applications of subjective logic.

Subjective trust networks

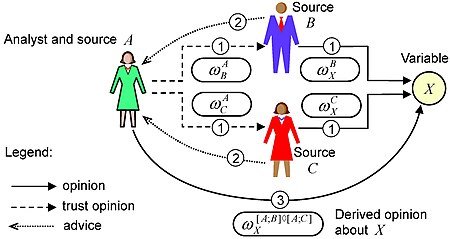

Subjective trust networks can be modelled with a combination of the transitivity and fusion operators. Let express the referral trust edge from to , and let express the belief edge from to . A subjective trust network can for example be expressed as as illustrated in the figure below.

The indices 1, 2 and 3 indicate the chronological order in which the trust edges and advice are formed. Thus, given the set of trust edges with index 1, the origin trustor receives advice from and , and is thereby able to derive belief in variable . By expressing each trust edge and belief edge as an opinion, it is possible for to derive belief in expressed as .

Trust networks can express the reliability of information sources, and can be used to determine subjective opinions about variables that the sources provide information about.

Evidence-based subjective logic (EBSL) describes an alternative trust-network computation, where the transitivity of opinions (discounting) is handled by applying weights to the evidence underlying the opinions.

Subjective Bayesian networks

In the Bayesian network below, and are parent variables and is the child variable. The analyst must learn the set of joint conditional opinions in order to apply the deduction operator and derive the marginal opinion on the variable . The conditional opinions express a conditional relationship between the parent variables and the child variable.

The deduced opinion is computed as . The joint evidence opinion can be computed as the product of independent evidence opinions on and , or as the joint product of partially dependent evidence opinions.

Subjective networks

The combination of a subjective trust network and a subjective Bayesian network is a subjective network. The subjective trust network can be used to obtain from various sources the opinions to be used as input opinions to the subjective Bayesian network, as illustrated in the figure below.

Traditional Bayesian network typically do not take into account the reliability of the sources. In subjective networks, the trust in sources is explicitly taken into account.

![{\displaystyle b_{x},d_{x},u_{x},a_{x}\in [0,1]\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fc69e84d9e4d6dfb035e023ea153ca9e4dc3b573)

![{\displaystyle b_{X}(x),u_{X},a_{X}(x)\in [0,1]\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b9e34897588c50f9c6c70ba8a3fce7a246e5a4a3)

![{\displaystyle [A;B,X]\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dd5d0a49e1ec0639e080f8bb390b21943c0f0429)

![{\displaystyle [A;B]:[B,X]\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e09e5be9204859d573e2a1307424c5a9870bdf10)

![{\displaystyle [A;B]\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c2a0182738e066b0e5b6238dc9987de727520552)

![{\displaystyle [B,X]\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/206ac409468219528d71f1ce2963162e786fac4e)

![{\displaystyle ([A;B]:[B,X])\diamond ([A;C]:[C,X])\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b9eb8d05820f512c757bf070bc34187f7db8201a)

![{\displaystyle \omega _{X}^{A}=\omega _{X}^{[A;B]\diamond [A;C]}=(\omega _{B}^{A}\otimes \omega _{X}^{B})\oplus (\omega _{C}^{A}\otimes \omega _{X}^{C})\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a6d459b001ad7d834fa052657e45341854729dad)