The intentional stance is a term coined by philosopher Daniel Dennett for the level of abstraction in which we view the behavior of an entity in terms of mental properties. It is part of a theory of mental content proposed by Dennett, which provides the underpinnings of his later works on free will, consciousness, folk psychology, and evolution.

Here is how it works: first you decide to treat the object whose behavior is to be predicted as a rational agent; then you figure out what beliefs that agent ought to have, given its place in the world and its purpose. Then you figure out what desires it ought to have, on the same considerations, and finally you predict that this rational agent will act to further its goals in the light of its beliefs. A little practical reasoning from the chosen set of beliefs and desires will in most instances yield a decision about what the agent ought to do; that is what you predict the agent will do.

— Daniel Dennett, The Intentional Stance, p. 17

Dennett and intentionality

Dennett (1971, p. 87) states that he took the concept of "intentionality" from the work of the German philosopher Franz Brentano. When clarifying the distinction between mental phenomena (viz., mental activity) and physical phenomena, Brentano (p. 97) argued that, in contrast with physical phenomena, the "distinguishing characteristic of all mental phenomena" was "the reference to something as an object" – a characteristic he called "intentional inexistence". Dennett constantly speaks of the "aboutness" of intentionality; for example: "the aboutness of the pencil marks composing a shopping list is derived from the intentions of the person whose list it is" (Dennett, 1995, p. 240).

John Searle (1999, pp. 85) stresses that "competence" in predicting/explaining human behaviour involves being able to both recognize others as "intentional" beings, and interpret others' minds as having "intentional states" (e.g., beliefs and desires):

- "The primary evolutionary role of the mind is to relate us in certain ways to the environment, and especially to other people. My subjective states relate me to the rest of the world, and the general name of that relationship is "intentionality." These subjective states include beliefs and desires, intentions and perceptions, as well as loves and hates, fears and hopes. "Intentionality," to repeat, is the general term for all the various forms by which the mind can be directed at, or be about, or of, objects and states of affairs in the world." (p.85)

According to Dennett (1987, pp. 48–49), folk psychology provides a systematic, "reason-giving explanation" for a particular action, and an account of the historical origins of that action, based on deeply embedded assumptions about the agent; namely that:

- (a) the agent's action was entirely rational;

- (b) the agent's action was entirely reasonable (in the prevailing circumstances);

- (c) the agent held certain beliefs;

- (d) the agent desired certain things; and

- (e) the agent's future action could be systematically predicted from the beliefs and desires so ascribed.

This approach is also consistent with the earlier work of Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel, whose joint study revealed that, when subjects were presented with an animated display of 2-dimensional shapes, they were inclined to ascribe intentions to the shapes.

Further, Dennett (1987, p. 52) argues that, based on our fixed personal views of what all humans ought to believe, desire and do, we predict (or explain) the beliefs, desires and actions of others "by calculating in a normative system"; and, driven by the reasonable assumption that all humans are rational beings – who do have specific beliefs and desires and do act on the basis of those beliefs and desires in order to get what they want – these predictions/explanations are based on four simple rules:

- The agent's beliefs are those a rational individual ought to have (i.e., given their "perceptual capacities", "epistemic needs" and "biography");

- In general, these beliefs "are both true and relevant to [their] life;

- The agent's desires are those a rational individual ought to have (i.e., given their "biological needs", and "the most practicable means of satisfying them") in order to further their "survival" and "procreation" needs; and

- The agent's behaviour will be composed of those acts a rational individual holding those beliefs (and having those desires) ought to perform.

Dennett's three levels

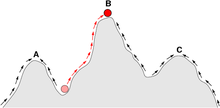

The core idea is that, when understanding, explaining, and/or predicting the behavior of an object, we can choose to view it at varying levels of abstraction. The more concrete the level, the more accurate in principle our predictions are; the more abstract, the greater the computational power we gain by zooming out and skipping over the irrelevant details.

Dennett defines three levels of abstraction, attained by adopting one of three entirely different "stances", or intellectual strategies: the physical stance; the design stance; and the intentional stance:

- The most concrete is the physical stance, the domain of physics and chemistry, which makes predictions from knowledge of the physical constitution of the system and the physical laws that govern its operation; and thus, given a particular set of physical laws and initial conditions, and a particular configuration, a specific future state is predicted (this could also be called the "structure stance"). At this level, we are concerned with such things as mass, energy, velocity, and chemical composition. When we predict where a ball is going to land based on its current trajectory, we are taking the physical stance. Another example of this stance comes when we look at a strip made up of two types of metal bonded together and predict how it will bend as the temperature changes, based on the physical properties of the two metals.

- Somewhat more abstract is the design stance, the domain of biology and engineering, which requires no knowledge of the physical constitution or the physical laws that govern a system's operation. Based on an implicit assumption that there is no malfunction in the system, predictions are made from knowledge of the purpose of the system's design (this could also be called the "teleological stance"). At this level, we are concerned with such things as purpose, function and design. When we predict that a bird will fly when it flaps its wings on the basis that wings are made for flying, we are taking the design stance. Likewise, we can understand the bimetallic strip as a particular type of thermometer, not concerning ourselves with the details of how this type of thermometer happens to work. We can also recognize the purpose that this thermometer serves inside a thermostat and even generalize to other kinds of thermostats that might use a different sort of thermometer. We can even explain the thermostat in terms of what it's good for, saying that it keeps track of the temperature and turns on the heater whenever it gets below a minimum, turning it off once it reaches a maximum.

- Most abstract is the intentional stance, the domain of software and minds, which requires no knowledge of either structure or design, and "[clarifies] the logic of mentalistic explanations of behaviour, their predictive power, and their relation to other forms of explanation" (Bolton & Hill, 1996, p. 24). Predictions are made on the basis of explanations expressed in terms of meaningful mental states; and, given the task of predicting or explaining the behaviour of a specific agent (a person, animal, corporation, artifact, nation, etc.), it is implicitly assumed that the agent will always act on the basis of its beliefs and desires in order to get precisely what it wants (this could also be called the "folk psychology stance"). At this level, we are concerned with such things as belief, thinking and intent. When we predict that the bird will fly away because it knows the cat is coming and is afraid of getting eaten, we are taking the intentional stance. Another example would be when we predict that Mary will leave the theater and drive to the restaurant because she sees that the movie is over and is hungry.

- In 1971, Dennett also postulated that, whilst "the intentional stance presupposes neither lower stance", there may well be a fourth, higher level: a "truly moral stance toward the system" – the "personal stance" – which not only "presupposes the intentional stance" (viz., treats the system as rational) but also "views it as a person" (1971/1978, p. 240).

A key point is that switching to a higher level of abstraction has its risks as well as its benefits. For example, when we view both a bimetallic strip and a tube of mercury as thermometers, we can lose track of the fact that they differ in accuracy and temperature range, leading to false predictions as soon as the thermometer is used outside the circumstances for which it was designed. The actions of a mercury thermometer heated to 500 °C can no longer be predicted on the basis of treating it as a thermometer; we have to sink down to the physical stance to understand it as a melted and boiled piece of junk. For that matter, the "actions" of a dead bird are not predictable in terms of beliefs or desires.

Even when there is no immediate error, a higher-level stance can simply fail to be useful. If we were to try to understand the thermostat at the level of the intentional stance, ascribing to it beliefs about how hot it is and a desire to keep the temperature just right, we would gain no traction over the problem as compared to staying at the design stance, but we would generate theoretical commitments that expose us to absurdities, such as the possibility of the thermostat not being in the mood to work today because the weather is so nice. Whether to take a particular stance, then, is determined by how successful that stance is when applied.

Dennett argues that it is best to understand human behavior at the level of the intentional stance, without making any specific commitments to any deeper reality of the artifacts of folk psychology. In addition to the controversy inherent in this, there is also some dispute about the extent to which Dennett is committing to realism about mental properties. Initially, Dennett's interpretation was seen as leaning more towards instrumentalism, but over the years, as this idea has been used to support more extensive theories of consciousness, it has been taken as being more like Realism. His own words hint at something in the middle, as he suggests that the self is as real as a center of gravity, "an abstract object, a theorist's fiction", but operationally valid.

As a way of thinking about things, Dennett's intentional stance is entirely consistent with everyday commonsense understanding; and, thus, it meets Eleanor Rosch's (1978, p. 28) criterion of the "maximum information with the least cognitive effort". Rosch argues that, implicit within any system of categorization, are the assumptions that:

- (a) the major purpose of any system of categorization is to reduce the randomness of the universe by providing "maximum information with the least cognitive effort", and

- (b) the real world is structured and systematic, rather than being arbitrary or unpredictable. Thus, if a particular way of categorizing information does, indeed, "provide maximum information with the least cognitive effort", it can only do so because the structure of that particular system of categories corresponds with the perceived structure of the real world.

Also, the intentional stance meets the criteria Dennett specified (1995, pp. 50–51) for algorithms:

- (1) Substrate Neutrality: It is a "mechanism" that produces results regardless of the material used to perform the procedure ("the power of the procedure is due to its logical structure, not the causal powers of the materials used in the instantiation").

- (2) Underlying Mindlessness: Each constituent step, and each transition between each step, is so utterly simple, that they can be performed by a "dutiful idiot".

- (3) Guaranteed Results: "Whatever it is that an algorithm does, it always does it, if it is executed without misstep. An algorithm is a foolproof recipe."

Variants of Dennett's three stances

The general notion of a three level system was widespread in the late 1970s/early 1980s; for example, when discussing the mental representation of information from a cognitive psychology perspective, Glass and his colleagues (1979, p. 24) distinguished three important aspects of representation:

- (a) the content ("what is being represented");

- (b) the code ("the format of the representation"); and

- (c) the medium ("the physical realization of the code").

Other significant cognitive scientists who also advocated a three level system were Allen Newell, Zenon Pylyshyn, and David Marr. The parallels between the four representations (each of which implicitly assumed that computers and human minds displayed each of the three distinct levels) are detailed in the following table:

| Daniel Dennett "Stances" |

Zenon Pylyshyn "Levels of Organization" |

Allen Newell "Levels of Description" |

David Marr "Levels of Analysis" |

|---|---|---|---|

Physical Stance. |

Physical Level, or Biological Level. | Physical Level, or Device Level. | Hardware Implementation Level. |

Design Stance. |

Symbol Level. | Program Level, or Symbol Level. | Representation and Algorithm Level. |

Intentional Stance. |

Semantic, or Knowledge Level. | Knowledge Level. | Computational Theory Level. |

Objections and replies

The most obvious objection to Dennett is the intuition that it "matters" to us whether an object has an inner life or not. The claim is that we don't just imagine the intentional states of other people in order to predict their behaviour; the fact that they have thoughts and feelings just like we do is central to notions such as trust, friendship and love. The Blockhead argument proposes that someone, Jones, has a twin who is in fact not a person but a very sophisticated robot which looks and acts like Jones in every way, but who (it is claimed) somehow does not have any thoughts or feelings at all, just a chip which controls his behaviour; in other words, "the lights are on but no one's home". According to the intentional systems theory (IST), Jones and the robot have precisely the same beliefs and desires, but this is claimed to be false. The IST expert assigns the same mental states to Blockhead as he does to Jones, "whereas in fact [Blockhead] has not a thought in his head." Dennett has argued against this by denying the premise, on the basis that the robot is a philosophical zombie and therefore metaphysically impossible. In other words, if something acts in all ways conscious, it necessarily is, as consciousness is defined in terms of behavioral capacity, not ineffable qualia.

Another objection attacks the premise that treating people as ideally rational creatures will yield the best predictions. Stephen Stich argues that people often have beliefs or desires which are irrational or bizarre, and IST doesn't allow us to say anything about these. If the person's "environmental niche" is examined closely enough, and the possibility of malfunction in their brain (which might affect their reasoning capacities) is looked into, it may be possible to formulate a predictive strategy specific to that person. Indeed this is what we often do when someone is behaving unpredictably — we look for the reasons why. In other words, we can only deal with irrationality by contrasting it against the background assumption of rationality. This development significantly undermines the claims of the intentional stance argument.

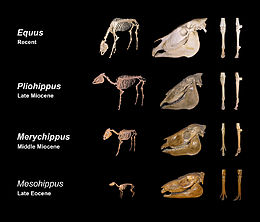

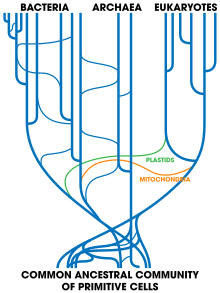

The rationale behind the intentional stance is based on evolutionary theory, particularly the notion that the ability to make quick predictions of a system's behaviour based on what we think it might be thinking was an evolutionary adaptive advantage. The fact that our predictive powers are not perfect is a further result of the advantages sometimes accrued by acting contrary to expectations.

Neural evidence

Philip Robbins and Anthony I. Jack suggest that "Dennett's philosophical distinction between the physical and intentional stances has a lot going for it" from the perspective of psychology and neuroscience. They review studies on abilities to adopt an intentional stance (variously called "mindreading", "mentalizing", or "theory of mind") as distinct from adopting a physical stance ("folk physics", "intuitive physics", or "theory of body"). Autism seems to be a deficit in the intentional stance with preservation of the physical stance, while Williams syndrome can involve deficits in the physical stance with preservation of the intentional stance. This tentatively suggests a double dissociation of intentional and physical stances in the brain. However, most studies have found no evidence of impairment in autistic individuals' ability to understand other people's basic intentions or goals; instead, data suggests that impairments are found in understanding more complex social emotions or in considering others' viewpoints.

Robbins and Jack point to a 2003 study in which participants viewed animated geometric shapes in different "vignettes," some of which could be interpreted as constituting social interaction, while others suggested mechanical behavior. Viewing social interactions elicited activity in brain regions associated with identifying faces and biological objects (posterior temporal cortex), as well as emotion processing (right amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex). Meanwhile, the mechanical interactions activated regions related to identifying objects like tools that can be manipulated (posterior temporal lobe). The authors suggest "that these findings reveal putative 'core systems' for social and mechanical understanding that are divisible into constituent parts or elements with distinct processing and storage capabilities."

Phenomenal stance

Robbins and Jack argue for an additional stance beyond the three that Dennett outlined. They call it the phenomenal stance: Attributing consciousness, emotions, and inner experience to a mind. The explanatory gap of the hard problem of consciousness illustrates this tendency of people to see phenomenal experience as different from physical processes. The authors suggest that psychopathy may represent a deficit in the phenomenal but not intentional stance, while people with autism appear to have intact moral sensibilities, just not mind-reading abilities. These examples suggest a double dissociation between the intentional and phenomenal stances.

In a follow-up paper, Robbins and Jack describe four experiments about how the intentional and phenomenal stances relate to feelings of moral concern. The first two experiments showed that talking about lobsters as strongly emotional led to a much greater sentiment that lobsters deserved welfare protections than did talking about lobsters as highly intelligent. The third and fourth studies found that perceiving an agent as vulnerable led to greater attributions of phenomenal experience. Also, people who scored higher on the empathetic-concern subscale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index had generally higher absolute attributions of mental experience.

Bryce Huebner (2010) performed two experimental philosophy studies to test students' ascriptions of various mental states to humans compared with cyborgs and robots. Experiment 1 showed that while students attributed both beliefs and pains most strongly to humans, they were more willing to attribute beliefs than pains to robots and cyborgs. "[T]hese data seem to confirm that commonsense psychology does draw a distinction between phenomenal and non-phenomenal states—and this distinction seems to be dependent on the structural properties of an entity in a way that ascriptions of non-phenomenal states are not." However, this conclusion is only tentative in view of the high variance among participants. Experiment 2 showed analogous results: Both beliefs and happiness were ascribed most strongly to biological humans, and ascriptions of happiness to robots or cyborgs were less common than ascriptions of beliefs.