Farthest South refers to the most southerly latitude reached by explorers before the first successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911.

Significant steps on the road to the pole were the discovery of lands south of Cape Horn in 1619, Captain James Cook's crossing of the Antarctic Circle in 1773, and the earliest confirmed sightings of the Antarctic mainland in 1820. From the late 19th century onward, the quest for Farthest South latitudes became a race to reach the pole, which culminated in Roald Amundsen's success in December 1911.

In the years before reaching the pole was a realistic objective, other motives drew adventurers southward. Initially, the driving force was the discovery of new trade routes between Europe and the Far East. After such routes had been established and the main geographical features of the Earth had been broadly mapped, the lure for mercantile adventurers was the great fertile continent of "Terra Australis" which, according to myth, lay hidden in the south. Belief in the existence of this supposed land of plenty persisted well into the 18th century; explorers were reluctant to accept the truth that slowly emerged, of a cold, harsh environment in the lands of the Southern Ocean.

James Cook's voyages of 1772–1775 demonstrated conclusively the likely hostile nature of any hidden lands. This caused a shift of emphasis in the first half of the 19th century, away from trade and towards sealing and whaling, and then exploration and discovery. After the first overwintering on continental Antarctica in 1898–99 (Adrien de Gerlache), the prospect of reaching the South Pole appeared realistic, and the race for the pole began. The British were pre-eminent in this endeavour, which was characterised by the rivalry between Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Shackleton's efforts fell short; Scott reached the pole in January 1912 only to find that he had been beaten by the Norwegian Amundsen.

Early voyagers

In 1494, the principal maritime powers, Portugal and Spain, signed a treaty which drew a line down the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and allocated all trade routes to the east of the line to Portugal. That gave Portugal dominance of the only known route to the east–via the Cape of Good Hope and Indian Ocean, which left Spain, and later other countries, to seek a western route to the Pacific. The exploration of the south began as part of the search for such a route.

Unlike the Arctic, there is no evidence of human visitation or habitation in 'Antarctica' or the islands around it prior to European exploration. However, the most southerly parts of South America were already inhabited by tribes such as the Selk'nam/Ona, the Yagán/Yámana, the Alacaluf and the Haush. The Haush in particular made regular trips to Isla de los Estados, which was 29 kilometres (18 mi) from the main island of Tierra del Fuego, suggesting that some of them may have been capable of reaching the islands near Cape Horn. Fuegian Indian artefacts and canoe remnants have also been discovered on the Falkland Islands, suggesting the capacity for even longer sea journeys. Chilean scientists have claimed that Amerinds visited the South Shetland Islands, due to stone artifacts recovered from bottom-sampling operations in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, and Discovery Bay, Greenwich Island; however, the artifacts—two arrowheads—were later found to have been planted, possibly to reinforce Chilean claims to the area.

While the natives of Tierra del Fuego were not capable of true oceanic travel, there is some evidence of Polynesian visits to some of the sub antarctic islands to the south of New Zealand, although these are further from Antarctica than South America. There are also remains of a Polynesian settlement dating back to the 13th century on Enderby Island in the Auckland Islands. According to ancient legends, around the year 650 the Polynesian traveller Ui-te-Rangiora led a fleet of Waka Tīwai south until they reached "a place of bitter cold where rock-like structures rose from a solid sea". It is unclear from the legends how far south Ui-te-Rangiora penetrated, but it appears that he observed ice in large quantities. A shard of undated, unidentified pottery, reported as found in 1886 in the Antipodes Islands, has been associated with this expedition.

Ferdinand Magellan

Although Portuguese by birth, Ferdinand Magellan transferred his allegiance to King Charles I of Spain, on whose behalf he left Seville on 10 August 1519, with a squadron of five ships, in search of a western route to the Spice Islands in the East Indies. Success depended on finding a strait or passage through the South American land masses, or finding the southern tip of the continent and sailing around it. The South American coast was sighted on 6 December 1519, and Magellan moved cautiously southward, following the coast to reach latitude 49°S on 31 March 1520. Little if anything was known of the coast south of this point, so Magellan decided to wait out the southern winter here, and established the settlement of Puerto San Julian.

In September 1520, the voyage continued down the uncharted coast, and on 21 October reached 52°S. Here Magellan found a deep inlet which proved to be the strait he was seeking, later to be known by his name. Early in November 1520, as the squadron navigated through the strait, they reached its most southerly point at approximate latitude 54°S. This was a record Farthest South for a European navigator, though not the farthest southern penetration by man; the position was north of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago, where there is evidence of human settlement dating back thousands of years.

Francisco de Hoces

The first sighting of an ocean passage to the Pacific south of Tierra del Fuego is sometimes attributed to Francisco de Hoces of the Loaisa Expedition. In January 1526 his ship San Lesmes was blown south from the Atlantic entrance of the Magellan Strait to a point where the crew thought they saw a headland, and water beyond it, which indicated the southern extremity of the continent. There is speculation as to which headland they saw; conceivably it was Cape Horn. In parts of the Spanish-speaking world it is believed that de Hoces may have discovered the strait later known as the Drake Passage more than 50 years before Sir Francis Drake, the British privateer.

Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake sailed from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, in command of a fleet of five ships under his flagship Pelican, later renamed the Golden Hinde. His principal objective was plunder, not exploration; his initial targets were the unfortified Spanish towns on the Pacific coasts of Chile and Peru. Following Magellan's route, Drake reached Puerto San Julian on 20 June. After nearly two months in harbour, Drake left the port with a reduced fleet of three ships and a small pinnace. His ships entered the Magellan Strait on 23 August and emerged in the Pacific Ocean on 6 September.

Drake set a course to the north-west, but on the following day a gale scattered the ships. The Marigold was sunk by a giant wave; the Elizabeth managed to return into the Magellan Strait, later sailing eastwards back to England; the pinnace was lost later. The gales persisted for more than seven weeks. The Golden Hinde was driven far to the west and south, before clawing its way back towards land. On 22 October, the ship anchored off an island which Drake named "Elizabeth Island", where wood for the galley fires was collected and seals and penguins captured for food.

According to Drake's Portuguese pilot, Nuno da Silva, their position at the anchorage was 57°S. However, there is no island at that latitude. The as yet undiscovered Diego Ramírez Islands, at 56°30'S, are treeless and cannot have been the islands where Drake's crew collected wood. This indicates that the navigational calculation was faulty, and that Drake landed at or near the then unnamed Cape Horn, possibly on Horn Island itself. His final southern latitude can only be speculated as that of Cape Horn, at 55°59'S. In his report, Drake wrote: "The Uttermost Cape or headland of all these islands stands near 56 degrees, without which there is no main island to be seen to the southwards but that the Atlantic Ocean and the South Sea meet." This open sea south of Cape Horn became known as the Drake Passage even though Drake himself did not traverse it.

Willem Schouten

On 14 June 1615, Willem Schouten, with two ships Eendracht and Hoorn, set sail from Texel in the Netherlands in search of a western route to the Pacific. Hoorn was lost in a fire, but Eendracht continued southward. On 29 January 1616, Schouten reached what he discerned to be the southernmost cape of the South American continent; he named this point Kaap Hoorn (Cape Horn) after his hometown and his lost ship. Schouten's navigational readings are inaccurate—he placed Cape Horn at 57°48' south, when its actual position is 55°58'. His claim to have reached 58° south is unverified, although he sailed on westward to become the first European navigator to reach the Pacific via the Drake Passage.

Garcia de Nodal expedition

The next recorded navigation of the Drake Passage was achieved in February 1619, by the brothers Bartolome and Gonzalo Garcia de Nodal. The Garcia de Nodal expedition discovered a small group of islands about 60 nautical miles (100 km; 70 mi) south-west of Cape Horn, at latitude 56°30'S. They named these the Diego Ramirez Islands after the expedition's pilot. The islands remained the most southerly known land on earth until Captain James Cook's discovery of the South Sandwich Islands in 1775.

Other discoveries

Other voyages brought further discoveries in the southern oceans; in August 1592, the English seaman John Davis had taken shelter "among certain Isles never before discovered"—presumed to be the Falkland Islands. In 1675, the English merchant voyager Anthony de la Roché visited South Georgia (the first Antarctic land discovered); in 1739 the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Bouvet de Lozier discovered the remote Bouvet Island, and in 1772 his compatriot, Yves-Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec, found the Kerguelen Islands.

Early Antarctic explorers

Captain James Cook

The second of James Cook's historic voyages, 1772–1775, was primarily a search for the elusive Terra Australis Incognita that was still believed to lie somewhere in the unexplored latitudes below 40°S. Cook left England in September 1772 with two ships, HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure. After pausing at Cape Town, on 22 November the two ships sailed due south, but were driven to the east by heavy gales. They managed to edge further south, encountering their first pack ice on 10 December. This soon became a solid barrier, which tested Cook's seamanship as he manoeuvered for a passage through. Eventually, he found open water, and was able to continue south; on 17 January 1773, the expedition reached the Antarctic Circle at 66°20'S, the first ships to do so. Further progress was barred by ice, and the ships turned north-eastwards and headed for New Zealand, which they reached on 26 March.

During the ensuing months, the expedition explored the southern Pacific Ocean before Cook took Resolution south again—Adventure had retired back to South Africa after a confrontation with the New Zealand native population. This time Cook was able to penetrate deep beyond the Antarctic Circle, and on 30 January 1774 reached 71°10'S, his Farthest South, but the state of the ice made further southward travel impossible. This southern record would hold for 49 years.

In the course of his voyages in Antarctic waters, Cook had encircled the world at latitudes generally above 60°S, and saw nothing but bleak inhospitable islands, without a hint of the fertile continent which some still hoped lay in the south. Cook wrote that if any such continent existed it would be "a country doomed by nature", and that "no man will venture further than I have done, and the land to the South will never be explored". He concluded: "Should the impossible be achieved and the land attained, it would be wholly useless and of no benefit to the discoverer or his nation".

Searching for land

Despite Cook's prediction, the early 19th century saw numerous attempts to penetrate southward, and to discover new lands. In 1819, William Smith, in command of the brigantine Williams, discovered the South Shetland Islands, and in the following year Edward Bransfield, in the same ship, sighted the Trinity Peninsula at the northern extremity of Graham Land. A few days before Bransfield's discovery, on 27 January 1820, the Russian captain Fabian von Bellingshausen, in another Antarctic sector, had come within sight of the coast of what is now known as Queen Maud Land. He is thus credited as the first person to see the continent's mainland, although he did not make this claim himself. Bellingshausen made two circumnavigations mainly in latitudes between 60 and 67°S, and in January 1821 reached his most southerly point at 70°S, in a longitude close to that in which Cook had made his record 47 years earlier. In 1821 the American sealing captain John Davis led a party which landed on an uncharted stretch of land beyond the South Shetlands. "I think this Southern Land to be a Continent", he wrote in his ship's log. If his landing was not on an island, his party were the first to set foot on the Antarctic continent.

James Weddell

James Weddell was an Anglo-Scottish seaman who saw service in both the Royal Navy and the merchant marine before undertaking his first voyages to Antarctic waters. In 1819, in command of the 160-ton brigantine Jane which had been adapted for whaling, he set sail for the newly discovered whaling grounds of the South Sandwich Islands. His chief interest on this voyage was in finding the "Aurora Islands", which had been reported at 53°S, 48°W by the Spanish ship Aurora in 1762. He failed to discover this non-existent land, but his sealing activities showed a handsome profit.

In 1822 Weddell, again in command of Jane and this time accompanied by a smaller ship, the cutter Beaufoy, set sail for the south with instructions from his employers that, should the sealing prove barren, he was to "investigate beyond the track of former navigators". This suited Weddell's exploring instincts, and he equipped his vessel with chronometers, thermometers, compasses, barometers and charts. In January 1823 he probed the waters between the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands, looking for new land. Finding none, he turned southward down the 40°W meridian, deep into the sea that now bears his name. The season was unusually calm, and Weddell reported that "not a particle of ice of any description was to be seen". On 20 February 1823, he reached a new Farthest South of 74°15'S, three degrees beyond Cook's former record. Unaware that he was close to land, Weddell decided to return northward from this point, convinced that the sea continued as far as the South Pole. Another two days' sailing would likely have brought him within sight of Coats Land, which was not discovered until 1904, by William Speirs Bruce during the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, 1902–1904. On his return to England, Weddell's claim to have exceeded Cook's record by such a margin "caused some raised eyebrows", but was soon accepted.

Benjamin Morrell

In November 1823, the American sealing captain Benjamin Morrell reached the South Sandwich Islands in the schooner Wasp. According to his own later account he then sailed south, unconsciously following the track taken by James Weddell a month previously. Morrell claimed to have reached 70°14'S, at which point he turned north because the ship's stoves were running short of fuel—otherwise, he says, he could have "reached 85° without the least doubt". After turning, he claimed to have encountered land which he described in some detail, and which he named New South Greenland. This land proved not to exist. Morrell's reputation as a liar and a fraud means that most of his geographical claims have been dismissed by scholars, although attempts have been made to rationalise his assertions.

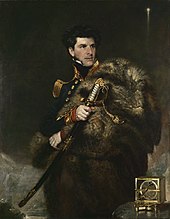

James Clark Ross

James Clark Ross's 1839–1843 Antarctic expedition in HMS Erebus and HMS Terror was a full-scale Royal Naval enterprise, the principal function of which was to test current theories on magnetism, and to try to locate the South Magnetic Pole. The expedition had first been proposed by leading astronomer Sir John Herschel, and was supported by the Royal Society and the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Ross had considerable past experience in magnetic observation and Arctic exploration; in May 1831 he had been a member of a party that had reached the location of the North Magnetic Pole, and he was an obvious choice as commander.

The expedition left England on 30 September 1839, and after a voyage that was slowed by the many stops required to carry out work on magnetism, it reached Tasmania in August 1840. Following a three-month break imposed by the southern winter, they sailed south-east on 12 November 1840, and crossed the Antarctic Circle on 1 January 1841. On 11 January a long mountainous coastline that stretched to the south was sighted. Ross named the land Victoria Land, and the mountains the Admiralty Range. He followed the coast southwards and passed Weddell's Farthest South point of 74°15'S on 23 January. A few days later, as they moved further eastward to avoid shore ice, they were met by the sight of twin volcanoes (one of them active), which were named Mount Erebus and Mount Terror, in honour of the expedition's ships.

The Great Ice Barrier (later to be called the "Ross Ice Shelf") stretched away east of these mountains, forming an impassable obstacle to further southward progress. In his search for a strait or inlet, Ross explored 300 nautical miles (560 km; 350 mi) along the edge of the barrier, and reached an approximate latitude of 78°S on or about 8 February 1841. He failed to find a suitable anchorage that would have allowed the ships to over-winter, so he returned to Tasmania, arriving there in April 1841.

The following season Ross returned and located an inlet in the Barrier face that enabled him, on 23 February 1842, to extend his Farthest South to 78°09'30"S, a record which would remain unchallenged for 58 years. Although Ross had not been able to land on the Antarctic continent, nor approach the location of the South Magnetic Pole, on his return to England in 1843 he was knighted for his achievements in geographical and scientific exploration.

Explorers of the Heroic Age

The oceanographic research voyage known as the Challenger Expedition, 1872–1876, explored Antarctic waters for several weeks, but did not approach the land itself; its research, however, proved the existence of an Antarctic continent beyond a reasonable doubt.

The impetus for what would become known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration came in 1895, when in an address to the Sixth International Geographical Congress in London, Professor Sir John Murray called for a resumption of Antarctic exploration: "a steady, continuous, laborious and systematic exploration of the whole southern region". He followed this call with an appeal to British patriotism: "Is the last great piece of maritime exploration on the surface of our Earth to be undertaken by Britons, or is it to be left to those who may be destined to succeed or supplant us on the Ocean?" During the following quarter-century, fifteen expeditions from eight different nations rose to this challenge. In the patriotic spirit engendered by Murray's call, and under the influence of RGS president Sir Clements Markham, British endeavours in the following years gave particular weight to the achievement of new Farthest South records, and began to develop the character of a race for the South Pole.

Carsten Borchgrevink

The Norwegian-born Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink had emigrated to Australia in 1888, where he worked on survey teams in Queensland and New South Wales before accepting a school teaching post. In 1894 he joined a sealing and whaling expedition to the Antarctic, led by Henryk Bull. In January 1895 Borchgrevink was one of a group from that expedition that claimed the first confirmed landing on the Antarctic continent, at Cape Adare.[ Borchgrevink determined to return with his own expedition, which would overwinter and explore inland, with the location of the South Magnetic Pole as an objective.

Borchgrevink went to England, where he was able to persuade the publishing magnate Sir George Newnes to finance him to the extent of £40,000, equivalent to £4.51 million in 2019, with the sole stipulation that, despite the shortage of British participants, the venture be styled the "British Antarctic Expedition". This was by no means the grand British expedition envisaged by Markham and the geographical establishment, who were hostile and dismissive of Borchgrevink. On 23 August 1898 the expedition ship Southern Cross left London for the Ross Sea, reaching Cape Adare on 17 February 1899. Here a shore party was landed and was the first to over-winter on the Antarctic mainland, in a prefabricated hut.

In January 1900, Southern Cross returned, picked up the shore party and, following the route which Ross had taken 60 years previously, sailed southward to the Great Ice Barrier, which they discovered had retreated some 30 miles (48 km) south since the days of Ross. A party consisting of Borchgrevink, William Colbeck and a Sami named Per Savio landed with sledges and dogs. This party ascended the Barrier and made the first sledge journey on the barrier surface; on 16 February 1900 they extended the Farthest South record to 78°50'S. On its return to England later in 1900, Borchgrevink's expedition was received without enthusiasm, despite its new southern record. Historian David Crane commented that if Borchgrevink had been a British naval officer, his contribution to Antarctic knowledge might have been better received, but "a Norwegian seaman/schoolmaster was never going to be taken seriously".

Robert Falcon Scott

The Discovery Expedition of 1901–1904 was Robert Falcon Scott's first Antarctic command. Although according to Edward Wilson the intention was to "reach the Pole if possible, or find some new land", there is nothing in Scott's writings, nor in the official objectives of the expedition, to indicate that the pole was a definite goal. However, a southern journey towards the pole was within Scott's formal remit to "explore the ice barrier of Sir James Ross ... and to endeavour to solve the very important physical and geographical questions connected with this remarkable ice formation".

The southern journey was undertaken by Scott, Wilson and Ernest Shackleton. The party set out on 1 November 1902 with various teams in support, and one of these, led by Michael Barne, passed Borchgrevink's Farthest South mark on 11 November, an event recorded with great high spirits in Wilson's diary. The march continued, initially in favourable weather conditions, but encountered increasing difficulties caused by the party's lack of ice travelling experience and the loss of all its dogs through a combination of poor diet and overwork. The 80°S mark was passed on 2 December, and four weeks later, on 30 December 1902, Wilson and Scott took a short ski trip from their southern camp to set a new Farthest South at (according to their measurements) 82°17'S. Modern maps, correlated with Shackleton's photograph and Wilson's drawing, put their final camp at 82°6'S, and the point reached by Scott and Wilson at 82°11'S, 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) beyond Borchgrevink's mark.

Ernest Shackleton

After his share in the Farthest South achievement of the Discovery Expedition, Ernest Shackleton suffered a physical collapse on the return journey, and was sent home with the expedition's relief vessel on orders from Scott; he bitterly resented it, and the two became rivals. Four years later, Shackleton organised his own polar venture, the Nimrod Expedition, 1907–1909. This was the first expedition to set the definite objective of reaching the South Pole, and to have a specific strategy for doing so.

To assist his endeavour, Shackleton adopted a mixed transport strategy, involving the use of Manchurian ponies as pack animals, as well as the more traditional dog-sledges. A specially adapted motor car was also taken. Although the dogs and the car were used during the expedition for a number of purposes, the task of assisting the group that would undertake the march to the pole fell to the ponies. The size of Shackleton's four-man polar party was dictated by the number of surviving ponies; of the ten that were embarked in New Zealand, only four had survived the 1908 winter.

Ernest Shackleton and three companions (Frank Wild, Eric Marshall and Jameson Adams) began their march on 29 October 1908. On 26 November they surpassed the farthest point reached by Scott's 1902 party. "A day to remember", wrote Shackleton in his journal, noting that they had reached this point in far less time than on the previous march with Scott. Shackleton's group continued southward, discovering and ascending the Beardmore Glacier to the polar plateau, and then marching on to reach their Farthest South point at 88°23'S, a mere 97 nautical miles (180 km; 112 mi) from the pole, on 9 January 1909. Here they planted the Union Jack presented to them by Queen Alexandra, and took possession of the plateau in the name of King Edward VII, before shortages of food and supplies forced them to turn back north. This was, at the time, the closest convergence on either pole. The increase of more than six degrees south from Scott's previous record was the greatest extension of Farthest South since Captain Cook's 1773 mark. Shackleton was treated as a hero on his return to England. His record was to stand for less than three years, being passed by Amundsen on 7 December 1911.

Polar conquest

In the wake of Shackleton's near miss, Robert Scott organised the Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–1913, in which securing the South Pole for the British Empire was an explicitly stated prime objective. As he planned his expedition, Scott saw no reason to believe that his effort would be contested. However, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, who had been developing plans for a North Pole expedition, changed his mind when, in September 1909, the North Pole was claimed in quick succession by the Americans Frederick Cook and Robert Peary. Amundsen resolved to go south instead.

Amundsen concealed his revised intentions until his ship, Fram, was in the Atlantic and beyond communication. Scott was notified by telegram that a rival was in the field, but had little choice other than to continue with his own plans. Meanwhile, Fram arrived at the Ross Ice Shelf on 11 January 1911, and by 14 January had found the inlet, or "Bay of Whales", where Borchgrevink had made his landing eleven years earlier. This became the location of Amundsen's base camp, Framheim.

After nine months' preparation, Amundsen's polar journey began on 20 October 1911. Avoiding the known route to the polar plateau via the Beardmore Glacier, Amundsen led his party of five due south, reaching the Transantarctic Mountains on 16 November. They discovered the Axel Heiberg Glacier, which provided them with a direct route to the polar plateau and on to the pole. Shackleton's Farthest South mark was passed on 7 December, and the South Pole was reached on 14 December 1911. The Norwegian party's greater skills with the techniques of ice travel, using ski and dogs, had proved decisive in their success. Scott's five-man team reached the same point 33 days later, and perished during their return journey. Since Cook's journeys, every expedition that had held the Farthest South record before Amundsen's conquest had been British; however, the final triumph indisputably belonged to the Norwegians.

Later history

After Scott's retreat from the pole in January 1912, the location remained unvisited for nearly 18 years. On 28 November 1929, US Navy Commander (later Rear-Admiral) Richard E. Byrd and three others completed the first aircraft flight over the South Pole. Twenty-seven years later, Rear-Admiral George J. Dufek became the first person to set foot on the pole since Scott, when on 31 October 1956 he and the crew of R4D-5 Skytrain "Que Sera Sera" landed at the pole. Between November 1956 and February 1957, the first permanent South Pole research station was erected and christened the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station in honour of the pioneer explorers. Since then the station had been substantially extended, and in 2008 was housing up to 150 scientific staff and support personnel. Dufek gave considerable assistance to the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955–1958, led by Vivian Fuchs, which on 19 January 1958 became the first party to reach the pole overland since Scott.