Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded language to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information that is being presented. Propaganda can be found in a wide variety of different contexts.

In the 20th century, the English term propaganda was often associated with a manipulative approach, but historically, propaganda had been a neutral descriptive term of any material that promotes certain opinions or ideologies.

A wide range of materials and media are used for conveying propaganda messages, which changed as new technologies were invented, including paintings, cartoons, posters, pamphlets, films, radio shows, TV shows, and websites. More recently, the digital age has given rise to new ways of disseminating propaganda, for example, bots and algorithms are currently being used to create computational propaganda and fake or biased news and spread it on social media.

Etymology

Propaganda is a modern Latin word, the neuter plural gerundive form of propagare, meaning 'to spread' or 'to propagate', thus propaganda means the things which are to be propagated. Originally this word derived from a new administrative body (congregation) of the Catholic Church created in 1622 as part of the Counter-Reformation, called the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for Propagating the Faith), or informally simply Propaganda. Its activity was aimed at "propagating" the Catholic faith in non-Catholic countries.

From the 1790s, the term began being used also to refer to propaganda in secular activities. The term began taking a pejorative or negative connotation in the mid-19th century, when it was used in the political sphere.

Some similar non-English terms retain some neutral or positive connotations. For example, in official party discourse, xuanchuan is treated as a more neutral or positive term, though it can be used pejoratively through protest or other informal settings within China.

Definitions

Propaganda was conceptualized as a form of influence designed to build social consensus. In the 20th century, the term propaganda emerged along with the rise of mass media, including newspapers and radio. As researchers began studying the effects of media, they used suggestion theory to explain how people could be influenced by emotionally-resonant persuasive messages. Harold Lasswell provided a broad definition of the term propaganda, writing it as: "the expression of opinions or actions carried out deliberately by individuals or groups with a view to influencing the opinions or actions of other individuals or groups for predetermined ends and through psychological manipulations." Garth Jowett and Victoria O'Donnell theorize that propaganda and persuasion are linked as humans use communication as a form of soft power through the development and cultivation of propaganda materials.

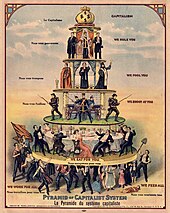

In a 1929 literary debate with Edward Bernays, Everett Dean Martin argues that, "Propaganda is making puppets of us. We are moved by hidden strings which the propagandist manipulates." In the 1920s and 1930s, propaganda was sometimes described as all-powerful. For example, Bernays acknowledged in his book Propaganda that "The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of."

NATO's 2011 guidance for military public affairs defines propaganda as "information, ideas, doctrines, or special appeals disseminated to influence the opinion, emotions, attitudes, or behaviour of any specified group in order to benefit the sponsor, either directly or indirectly".

History

Primitive forms of propaganda have been a human activity as far back as reliable recorded evidence exists. The Behistun Inscription (c. 515 BCE) detailing the rise of Darius I to the Persian throne is viewed by most historians as an early example of propaganda. Another striking example of propaganda during ancient history is the last Roman civil wars (44–30 BCE) during which Octavian and Mark Antony blamed each other for obscure and degrading origins, cruelty, cowardice, oratorical and literary incompetence, debaucheries, luxury, drunkenness and other slanders. This defamation took the form of uituperatio (Roman rhetorical genre of the invective) which was decisive for shaping the Roman public opinion at this time. Another early example of propaganda was from Genghis Khan. The emperor would send some of his men ahead of his army to spread rumors to the enemy. In many cases, his army was actually smaller than his opponents'.

Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I was the first ruler to utilize the power of the printing press for propaganda – in order to build his image, stir up patriotic feelings in the population of his empire (he was the first ruler who utilized one-sided battle reports – the early predecessors of modern newspapers or neue zeitungen – targeting the mass) and influence the population of his enemies. Propaganda during the Reformation, helped by the spread of the printing press throughout Europe, and in particular within Germany, caused new ideas, thoughts, and doctrine to be made available to the public in ways that had never been seen before the 16th century. During the era of the American Revolution, the American colonies had a flourishing network of newspapers and printers who specialized in the topic on behalf of the Patriots (and to a lesser extent on behalf of the Loyalists). Academic Barbara Diggs-Brown conceives that the negative connotations of the term "propaganda" are associated with the earlier social and political transformations that occurred during the French Revolutionary period movement of 1789 to 1799 between the start and the middle portion of the 19th century, in a time where the word started to be used in a nonclerical and political context.

The first large-scale and organised propagation of government propaganda was occasioned by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. After the defeat of Germany, military officials such as General Erich Ludendorff suggested that British propaganda had been instrumental in their defeat. Adolf Hitler came to echo this view, believing that it had been a primary cause of the collapse of morale and revolts in the German home front and Navy in 1918 (see also: Dolchstoßlegende). In Mein Kampf (1925) Hitler expounded his theory of propaganda, which provided a powerful base for his rise to power in 1933. Historian Robert Ensor explains that "Hitler...puts no limit on what can be done by propaganda; people will believe anything, provided they are told it often enough and emphatically enough, and that contradicters are either silenced or smothered in calumny." This was to be true in Germany and backed up with their army making it difficult to allow other propaganda to flow in. Most propaganda in Nazi Germany was produced by the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under Joseph Goebbels. Goebbels mentions propaganda as a way to see through the masses. Symbols are used towards propaganda such as justice, liberty and one's devotion to one's country. World War II saw continued use of propaganda as a weapon of war, building on the experience of WWI, by Goebbels and the British Political Warfare Executive, as well as the United States Office of War Information.

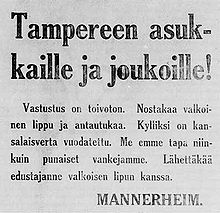

In the early 20th century, the invention of motion pictures (as in movies, diafilms) gave propaganda-creators a powerful tool for advancing political and military interests when it came to reaching a broad segment of the population and creating consent or encouraging rejection of the real or imagined enemy. In the years following the October Revolution of 1917, the Soviet government sponsored the Russian film industry with the purpose of making propaganda films (e.g., the 1925 film The Battleship Potemkin glorifies Communist ideals). In WWII, Nazi filmmakers produced highly emotional films to create popular support for occupying the Sudetenland and attacking Poland. The 1930s and 1940s, which saw the rise of totalitarian states and the Second World War, are arguably the "Golden Age of Propaganda". Leni Riefenstahl, a filmmaker working in Nazi Germany, created one of the best-known propaganda movies, Triumph of the Will. In 1942, the propaganda song Niet Molotoff was made in Finland during the Continuation War, making fun of the Red Army's failure in the Winter War, referring the song's name to the Soviet's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov. In the US, animation became popular, especially for winning over youthful audiences and aiding the U.S. war effort, e.g., Der Fuehrer's Face (1942), which ridicules Hitler and advocates the value of freedom. Some American war films in the early 1940s were designed to create a patriotic mindset and convince viewers that sacrifices needed to be made to defeat the Axis Powers. Others were intended to help Americans understand their Allies in general, as in films like Know Your Ally: Britain and Our Greek Allies. Apart from its war films, Hollywood did its part to boost American morale in a film intended to show how stars of stage and screen who remained on the home front were doing their part not just in their labors, but also in their understanding that a variety of peoples worked together against the Axis menace: Stage Door Canteen (1943) features one segment meant to dispel Americans' mistrust of the Soviets, and another to dispel their bigotry against the Chinese. Polish filmmakers in Great Britain created the anti-Nazi color film Calling Mr. Smith (1943) about Nazi crimes in German-occupied Europe and about lies of Nazi propaganda.

The West and the Soviet Union both used propaganda extensively during the Cold War. Both sides used film, television, and radio programming to influence their own citizens, each other, and Third World nations. Through a front organization called the Bedford Publishing Company, the CIA through a covert department called the Office of Policy Coordination disseminated over one million books to Soviet readers over the span of 15 years, including novels by George Orwell, Albert Camus, Vladimir Nabakov, James Joyce, and Pasternak in an attempt to promote anti-communist sentiment and sympathy of Western values. George Orwell's contemporaneous novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four portray the use of propaganda in fictional dystopian societies. During the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro stressed the importance of propaganda. Propaganda was used extensively by Communist forces in the Vietnam War as means of controlling people's opinions.

During the Yugoslav wars, propaganda was used as a military strategy by governments of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Croatia. Propaganda was used to create fear and hatred, and particularly to incite the Serb population against the other ethnicities (Bosniaks, Croats, Albanians and other non-Serbs). Serb media made a great effort in justifying, revising or denying mass war crimes committed by Serb forces during these wars.

Public perceptions

In the early 20th century the term propaganda was used by the founders of the nascent public relations industry to refer to their people. Literally translated from the Latin gerundive as "things that must be disseminated", in some cultures the term is neutral or even positive, while in others the term has acquired a strong negative connotation. The connotations of the term "propaganda" can also vary over time. For example, in Portuguese and some Spanish language speaking countries, particularly in the Southern Cone, the word "propaganda" usually refers to the most common manipulative media in business terms – "advertising".

In English, propaganda was originally a neutral term for the dissemination of information in favor of any given cause. During the 20th century, however, the term acquired a thoroughly negative meaning in western countries, representing the intentional dissemination of often false, but certainly "compelling" claims to support or justify political actions or ideologies. According to Harold Lasswell, the term began to fall out of favor due to growing public suspicion of propaganda in the wake of its use during World War I by the Creel Committee in the United States and the Ministry of Information in Britain: Writing in 1928, Lasswell observed, "In democratic countries the official propaganda bureau was looked upon with genuine alarm, for fear that it might be suborned to party and personal ends. The outcry in the United States against Mr. Creel's famous Bureau of Public Information (or 'Inflammation') helped to din into the public mind the fact that propaganda existed. ... The public's discovery of propaganda has led to a great of lamentation over it. Propaganda has become an epithet of contempt and hate, and the propagandists have sought protective coloration in such names as 'public relations council,' 'specialist in public education,' 'public relations adviser.' " In 1949, political science professor Dayton David McKean wrote, "After World War I the word came to be applied to 'what you don't like of the other fellow's publicity,' as Edward L. Bernays said...."

Contestation

The term is essentially contested and some have argued for a neutral definition, arguing that ethics depend on intent and context, while others define it as necessarily unethical and negative. Emma Briant defines it as "the deliberate manipulation of representations (including text, pictures, video, speech etc.) with the intention of producing any effect in the audience (e.g. action or inaction; reinforcement or transformation of feelings, ideas, attitudes or behaviours) that is desired by the propagandist." The same author explains the importance of consistent terminology across history, particularly as contemporary euphemistic synonyms are used in governments' continual efforts to rebrand their operations such as 'information support' and strategic communication. Other scholars also see benefits to acknowledging that propaganda can be interpreted as beneficial or harmful, depending on the message sender, target audience, message, and context.

David Goodman argues that the 1936 League of Nations "Convention on the Use of Broadcasting in the Cause of Peace" tried to create the standards for a liberal international public sphere. The Convention encouraged empathetic and neighborly radio broadcasts to other nations. It called for League prohibitions on international broadcast containing hostile speech and false claims. It tried to define the line between liberal and illiberal policies in communications, and emphasized the dangers of nationalist chauvinism. With Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia active on the radio, its liberal goals were ignored, while free speech advocates warned that the code represented restraints on free speech.

Types

Identifying propaganda has always been a problem. The main difficulties have involved differentiating propaganda from other types of persuasion, and avoiding a biased approach. Richard Alan Nelson provides a definition of the term: "Propaganda is neutrally defined as a systematic form of purposeful persuasion that attempts to influence the emotions, attitudes, opinions, and actions of specified target audiences for ideological, political or commercial purposes through the controlled transmission of one-sided messages (which may or may not be factual) via mass and direct media channels." The definition focuses on the communicative process involved – or more precisely, on the purpose of the process, and allow "propaganda" to be interpreted as positive or negative behavior depending on the perspective of the viewer or listener.

Propaganda can often be recognized by the rhetorical strategies used in its design. In the 1930s, the Institute for Propaganda Analysis identified a variety of propaganda techniques that were commonly used in newspapers and on the radio, which were the mass media of the time period. Propaganda techniques include "name calling" (using derogatory labels), "bandwagon" (expressing the social appeal of a message), or "glittering generalities" (using positive but imprecise language). With the rise of the internet and social media, Renee Hobbs identified four characteristic design features of many forms of contemporary propaganda: (1) it activates strong emotions; (2) it simplifies information; (3) it appeals to the hopes, fears, and dreams of a targeted audience; and (4) it attacks opponents.

Propaganda is sometimes evaluated based on the intention and goals of the individual or institution who created it. According to historian Zbyněk Zeman, propaganda is defined as either white, grey or black. White propaganda openly discloses its source and intent. Grey propaganda has an ambiguous or non-disclosed source or intent. Black propaganda purports to be published by the enemy or some organization besides its actual origins (compare with black operation, a type of clandestine operation in which the identity of the sponsoring government is hidden). In scale, these different types of propaganda can also be defined by the potential of true and correct information to compete with the propaganda. For example, opposition to white propaganda is often readily found and may slightly discredit the propaganda source. Opposition to grey propaganda, when revealed (often by an inside source), may create some level of public outcry. Opposition to black propaganda is often unavailable and may be dangerous to reveal, because public cognizance of black propaganda tactics and sources would undermine or backfire the very campaign the black propagandist supported.

The propagandist seeks to change the way people understand an issue or situation for the purpose of changing their actions and expectations in ways that are desirable to the interest group. Propaganda, in this sense, serves as a corollary to censorship in which the same purpose is achieved, not by filling people's minds with approved information, but by preventing people from being confronted with opposing points of view. What sets propaganda apart from other forms of advocacy is the willingness of the propagandist to change people's understanding through deception and confusion rather than persuasion and understanding. The leaders of an organization know the information to be one sided or untrue, but this may not be true for the rank and file members who help to disseminate the propaganda.

Religious

Propaganda was often used to influence opinions and beliefs on religious issues, particularly during the split between the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant churches or during the Crusades.

The sociologist Jeffrey K. Hadden has argued that members of the anti-cult movement and Christian counter-cult movement accuse the leaders of what they consider cults of using propaganda extensively to recruit followers and keep them. Hadden argued that ex-members of cults and the anti-cult movement are committed to making these movements look bad.

Propaganda against other religions in the same community or propaganda intended to keep political power in the hands of a religious elite can incite religious hate on a global or national scale. It could make use of many propaganda mediums. War, terrorism, riots, and other violent acts can result from it. It can also conceal injustices, inequities, exploitation, and atrocities, leading to ignorance-based indifference and alienation.

Wartime

In the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians exploited the figures from stories about Troy as well as other mythical images to incite feelings against Sparta. For example, Helen of Troy was even portrayed as an Athenian, whose mother Nemesis would avenge Troy. During the Punic Wars, extensive campaigns of propaganda were carried out by both sides. To dissolve the Roman system of socii and the Greek poleis, Hannibal released without conditions Latin prisoners that he had treated generously to their native cities, where they helped to disseminate his propaganda. The Romans on the other hand tried to portray Hannibal as a person devoid of humanity and would soon lose the favour of gods. At the same time, led by Q.Fabius Maximus, they organized elaborate religious rituals to protect Roman morale.

In the early sixteenth century, Maximilian I invented one kind of psychological warfare targeting the enemies. During his war against Venice, he attached pamphlets to balloons that his archers would shoot down. The content spoke of freedom and equality and provoked the populace to rebel against the tyrants (their Signoria).

Post–World War II usage of the word "propaganda" more typically refers to political or nationalist uses of these techniques or to the promotion of a set of ideas.

Propaganda is a powerful weapon in war; in certain cases, it is used to dehumanize and create hatred toward a supposed enemy, either internal or external, by creating a false image in the mind of soldiers and citizens. This can be done by using derogatory or racist terms (e.g., the racist terms "Jap" and "gook" used during World War II and the Vietnam War, respectively), avoiding some words or language or by making allegations of enemy atrocities. The goal of this was to demoralize the opponent into thinking what was being projected was actually true. Most propaganda efforts in wartime require the home population to feel the enemy has inflicted an injustice, which may be fictitious or may be based on facts (e.g., the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania by the German Navy in World War I). The home population must also believe that the cause of their nation in the war is just. In these efforts it was difficult to determine the accuracy of how propaganda truly impacted the war. In NATO doctrine, propaganda is defined as "Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or point of view." Within this perspective, the information provided does not need to be necessarily false but must be instead relevant to specific goals of the "actor" or "system" that performs it.

Propaganda is also one of the methods used in psychological warfare, which may also involve false flag operations in which the identity of the operatives is depicted as those of an enemy nation (e.g., The Bay of Pigs Invasion used CIA planes painted in Cuban Air Force markings). The term propaganda may also refer to false information meant to reinforce the mindsets of people who already believe as the propagandist wishes (e.g., During the First World War, the main purpose of British propaganda was to encourage men to join the army, and women to work in the country's industry. Propaganda posters were used because regular general radio broadcasting was yet to commence and TV technology was still under development). The assumption is that, if people believe something false, they will constantly be assailed by doubts. Since these doubts are unpleasant (see cognitive dissonance), people will be eager to have them extinguished, and are therefore receptive to the reassurances of those in power. For this reason, propaganda is often addressed to people who are already sympathetic to the agenda or views being presented. This process of reinforcement uses an individual's predisposition to self-select "agreeable" information sources as a mechanism for maintaining control over populations.

Propaganda may be administered in insidious ways. For instance, disparaging disinformation about the history of certain groups or foreign countries may be encouraged or tolerated in the educational system. Since few people actually double-check what they learn at school, such disinformation will be repeated by journalists as well as parents, thus reinforcing the idea that the disinformation item is really a "well-known fact", even though no one repeating the myth is able to point to an authoritative source. The disinformation is then recycled in the media and in the educational system, without the need for direct governmental intervention on the media. Such permeating propaganda may be used for political goals: by giving citizens a false impression of the quality or policies of their country, they may be incited to reject certain proposals or certain remarks or ignore the experience of others.

In the Soviet Union during the Second World War, the propaganda designed to encourage civilians was controlled by Stalin, who insisted on a heavy-handed style that educated audiences easily saw was inauthentic. On the other hand, the unofficial rumors about German atrocities were well founded and convincing. Stalin was a Georgian who spoke Russian with a heavy accent. That would not do for a national hero so starting in the 1930s all new visual portraits of Stalin were retouched to erase his Georgian facial characteristics and make him a more generalized Soviet hero. Only his eyes and famous moustache remained unaltered. Zhores Medvedev and Roy Medvedev say his "majestic new image was devised appropriately to depict the leader of all times and of all peoples."

Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights prohibits any propaganda for war as well as any advocacy of national or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence by law.

Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. The people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.

Simply enough the covenant specifically is not defining the content of propaganda. In simplest terms, an act of propaganda if used in a reply to a wartime act is not prohibited.

Advertising

Propaganda shares techniques with advertising and public relations, each of which can be thought of as propaganda that promotes a commercial product or shapes the perception of an organization, person, or brand. For example, after claiming victory in the 2006 Lebanon War, Hezbollah campaigned for broader popularity among Arabs by organizing mass rallies where Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah combined elements of the local dialect with classical Arabic to reach audiences outside Lebanon. Banners and billboards were commissioned in commemoration of the war, along with various merchandise items with Hezbollah's logo, flag color (yellow), and images of Nasrallah. T-shirts, baseball caps and other war memorabilia were marketed for all ages. The uniformity of messaging helped define Hezbollah's brand.

Journalistic theory generally holds that news items should be objective, giving the reader an accurate background and analysis of the subject at hand. On the other hand, advertisements evolved from the traditional commercial advertisements to include also a new type in the form of paid articles or broadcasts disguised as news. These generally present an issue in a very subjective and often misleading light, primarily meant to persuade rather than inform. Normally they use only subtle propaganda techniques and not the more obvious ones used in traditional commercial advertisements. If the reader believes that a paid advertisement is in fact a news item, the message the advertiser is trying to communicate will be more easily "believed" or "internalized". Such advertisements are considered obvious examples of "covert" propaganda because they take on the appearance of objective information rather than the appearance of propaganda, which is misleading. Federal law specifically mandates that any advertisement appearing in the format of a news item must state that the item is in fact a paid advertisement.

Edmund McGarry illustrates that advertising is more than selling to an audience but a type of propaganda that is trying to persuade the public and not to be balanced in judgement.

Politics

Propaganda has become more common in political contexts, in particular, to refer to certain efforts sponsored by governments, political groups, but also often covert interests. In the early 20th century, propaganda was exemplified in the form of party slogans. Propaganda also has much in common with public information campaigns by governments, which are intended to encourage or discourage certain forms of behavior (such as wearing seat belts, not smoking, not littering, and so forth). Again, the emphasis is more political in propaganda. Propaganda can take the form of leaflets, posters, TV, and radio broadcasts and can also extend to any other medium. In the case of the United States, there is also an important legal (imposed by law) distinction between advertising (a type of overt propaganda) and what the Government Accountability Office (GAO), an arm of the United States Congress, refers to as "covert propaganda." Propaganda is divided into two in political situations, they are preparation, meaning to create a new frame of mind or view of things, and operational, meaning they instigate actions.

Roderick Hindery argues that propaganda exists on the political left, and right, and in mainstream centrist parties. Hindery further argues that debates about most social issues can be productively revisited in the context of asking "what is or is not propaganda?" Not to be overlooked is the link between propaganda, indoctrination, and terrorism/counterterrorism. He argues that threats to destroy are often as socially disruptive as physical devastation itself.

Since 9/11 and the appearance of greater media fluidity, propaganda institutions, practices and legal frameworks have been evolving in the US and Britain. Briant shows how this included expansion and integration of the apparatus cross-government and details attempts to coordinate the forms of propaganda for foreign and domestic audiences, with new efforts in strategic communication. These were subject to contestation within the US Government, resisted by Pentagon Public Affairs and critiqued by some scholars. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (section 1078 (a)) amended the US Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (popularly referred to as the Smith-Mundt Act) and the Foreign Relations Authorization Act of 1987, allowing for materials produced by the State Department and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) to be released within U.S. borders for the Archivist of the United States. The Smith-Mundt Act, as amended, provided that "the Secretary and the Broadcasting Board of Governors shall make available to the Archivist of the United States, for domestic distribution, motion pictures, films, videotapes, and other material 12 years after the initial dissemination of the material abroad (...) Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors from engaging in any medium or form of communication, either directly or indirectly, because a United States domestic audience is or may be thereby exposed to program material, or based on a presumption of such exposure." Public concerns were raised upon passage due to the relaxation of prohibitions of domestic propaganda in the United States.

In the wake of this, the internet has become a prolific method of distributing political propaganda, benefiting from an evolution in coding called bots. Software agents or bots can be used for many things, including populating social media with automated messages and posts with a range of sophistication. During the 2016 U.S. election a cyber-strategy was implemented using bots to direct US voters to Russian political news and information sources, and to spread politically motivated rumors and false news stories. At this point it is considered commonplace contemporary political strategy around the world to implement bots in achieving political goals.

Techniques

Common media for transmitting propaganda messages include news reports, government reports, historical revision, junk science, books, leaflets, movies, radio, television, and posters. Some propaganda campaigns follow a strategic transmission pattern to indoctrinate the target group. This may begin with a simple transmission, such as a leaflet or advertisement dropped from a plane or an advertisement. Generally, these messages will contain directions on how to obtain more information, via a website, hotline, radio program, etc. (as it is seen also for selling purposes among other goals). The strategy intends to initiate the individual from information recipient to information seeker through reinforcement, and then from information seeker to opinion leader through indoctrination.

A number of techniques based in social psychological research are used to generate propaganda. Many of these same techniques can be found under logical fallacies, since propagandists use arguments that, while sometimes convincing, are not necessarily valid.

Some time has been spent analyzing the means by which the propaganda messages are transmitted. That work is important but it is clear that information dissemination strategies become propaganda strategies only when coupled with propagandistic messages. Identifying these messages is a necessary prerequisite to study the methods by which those messages are spread.

Propaganda can also be turned on its makers. For example, postage stamps have frequently been tools for government advertising, such as North Korea's extensive issues. The presence of Stalin on numerous Soviet stamps is another example. In Nazi Germany, Hitler frequently appeared on postage stamps in Germany and some of the occupied nations. A British program to parody these, and other Nazi-inspired stamps, involved airdropping them into Germany on letters containing anti-Nazi literature.

In 2018 a scandal broke in which the journalist Carole Cadwalladr, several whistleblowers and the academic Emma Briant revealed advances in digital propaganda techniques showing that online human intelligence techniques used in psychological warfare had been coupled with psychological profiling using illegally obtained social media data for political campaigns in the United States in 2016 to aid Donald Trump by the firm Cambridge Analytica. The company initially denied breaking laws but later admitted breaking UK law, the scandal provoking a worldwide debate on acceptable use of data for propaganda and influence.

Models

Persuasion in social psychology

The field of social psychology includes the study of persuasion. Social psychologists can be sociologists or psychologists. The field includes many theories and approaches to understanding persuasion. For example, communication theory points out that people can be persuaded by the communicator's credibility, expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. The elaboration likelihood model, as well as heuristic models of persuasion, suggest that a number of factors (e.g., the degree of interest of the recipient of the communication), influence the degree to which people allow superficial factors to persuade them. Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Herbert A. Simon won the Nobel prize for his theory that people are cognitive misers. That is, in a society of mass information, people are forced to make decisions quickly and often superficially, as opposed to logically.

According to William W. Biddle's 1931 article "A psychological definition of propaganda", "[t]he four principles followed in propaganda are: (1) rely on emotions, never argue; (2) cast propaganda into the pattern of "we" versus an "enemy"; (3) reach groups as well as individuals; (4) hide the propagandist as much as possible."

More recently, studies from behavioral science have become significant in understanding and planning propaganda campaigns, these include for example nudge theory which was used by the Obama Campaign in 2008 then adopted by the UK Government Behavioural Insights Team. Behavioural methodologies then became subject to great controversy in 2016 after the company Cambridge Analytica was revealed to have applied them with millions of people's breached Facebook data to encourage them to vote for Donald Trump.

Haifeng Huang argues that propaganda is not always necessarily about convincing a populace of its message (and may actually fail to do this) but instead can also function as a means of intimidating the citizenry and signalling the regime's strength and ability to maintain its control and power over society; by investing significant resources into propaganda, the regime can forewarn its citizens of its strength and deterring them from attempting to challenge it.

Propaganda theory and education

During the 1930s, educators in the United States and around the world became concerned about the rise of anti-Semitism and other forms of violent extremism. The Institute for Propaganda Analysis was formed to introduce methods of instruction for high school and college students, helping learners to recognize and desist propaganda by identifying persuasive techniques. This work built upon classical rhetoric and it was informed by suggestion theory and social scientific studies of propaganda and persuasion. In the 1950s, propaganda theory and education examined the rise of American consumer culture, and this work was popularized by Vance Packard in his 1957 book, The Hidden Persuaders. European theologian Jacques Ellul's landmark work, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes framed propaganda in relation to larger themes about the relationship between humans and technology. Media messages did not serve to enlighten or inspire, he argued. They merely overwhelm by arousing emotions and oversimplifying ideas, limiting human reasoning and judgement.

In the 1980s, academics recognized that news and journalism could function as propaganda when business and government interests were amplified by mass media. The propaganda model is a theory advanced by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky which argues systemic biases exist in mass media that are shaped by structural economic causes. It argues that the way in which commercial media institutions are structured and operate (e.g. through advertising revenue, concentration of media ownership, or access to sources) creates an inherent conflict of interest that make them act as propaganda for powerful political and commercial interests:

The 20th century has been characterized by three developments of great political importance: the growth of democracy, the growth of corporate power, and the growth of corporate propaganda as a means of protecting corporate power against democracy.

First presented in their book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), the propaganda model analyses commercial mass media as businesses that sell a product – access to readers and audiences – to other businesses (advertisers) and that benefit from access to information from government and corporate sources to produce their content. The theory postulates five general classes of "filters" that shape the content that is presented in news media: ownership of the medium, reliance on advertising revenue, access to news sources, threat of litigation and commercial backlash (flak), and anti-communism and "fear ideology". The first three (ownership, funding, and sourcing) are generally regarded by the authors as being the most important. Although the model was based mainly on the characterization of United States media, Chomsky and Herman believe the theory is equally applicable to any country that shares the basic political economic structure, and the model has subsequently been applied by other scholars to study media bias in other countries.

By the 1990s, the topic of propaganda was no longer a part of public education, having been relegated to a specialist subject. Secondary English educators grew fearful of the study of propaganda genres, choosing to focus on argumentation and reasoning instead of the highly emotional forms of propaganda found in advertising and political campaigns. In 2015, the European Commission funded Mind Over Media, a digital learning platform for teaching and learning about contemporary propaganda. The study of contemporary propaganda is growing in secondary education, where it is seen as a part of language arts and social studies education.

Self-propaganda

Self-propaganda is a form of propaganda that refers to the act of an individual convincing themself of something, no matter how irrational that idea may be. Self propaganda makes it easier for individuals to justify their own actions as well as the actions of others. Self-propaganda works oftentimes to lessen the cognitive dissonance felt by individuals when their personal actions or the actions of their government do not line up with their moral beliefs. Self-propaganda is a type of self deception. Self-propaganda can have a negative impact on those who perpetuate the beliefs created by using self-propaganda.

Children

Of all the potential targets for propaganda, children are the most vulnerable because they are the least prepared with the critical reasoning and contextual comprehension they need to determine whether a message is a propaganda or not. The attention children give their environment during development, due to the process of developing their understanding of the world, causes them to absorb propaganda indiscriminately. Also, children are highly imitative: studies by Albert Bandura, Dorothea Ross and Sheila A. Ross in the 1960s indicated that, to a degree, socialization, formal education and standardized television programming can be seen as using propaganda for the purpose of indoctrination. The use of propaganda in schools was highly prevalent during the 1930s and 1940s in Germany in the form of the Hitler Youth.

Anti-Semitic propaganda for children

In Nazi Germany, the education system was thoroughly co-opted to indoctrinate the German youth with anti-Semitic ideology. From the 1920s on, the Nazi Party targeted German youth as one of their special audience for its propaganda messages. Schools and texts mirrored what the Nazis aimed of instilling in German youth through the use and promotion of racial theory. Julius Streicher, the editor of Der Sturmer, headed a publishing house that disseminated anti-Semitic propaganda picture books in schools during the Nazi dictatorship. This was accomplished through the National Socialist Teachers League, of which 97% of all German teachers were members in 1937.

The League encouraged the teaching of racial theory. Picture books for children such as Trust No Fox on his Green Heath and No Jew on his Oath, Der Giftpilz (translated into English as The Poisonous Mushroom) and The Poodle-Pug-Dachshund-Pinscher were widely circulated (over 100,000 copies of Trust No Fox... were circulated during the late 1930s) and contained depictions of Jews as devils, child molesters and other morally charged figures. Slogans such as "Judas the Jew betrayed Jesus the German to the Jews" were recited in class. During the Nuremberg Trial, Trust No Fox on his Green Heath and No Jew on his Oath, and Der Giftpilz were received as documents in evidence because they document the practices of the Nazis The following is an example of a propagandistic math problem recommended by the National Socialist Essence of Education: "The Jews are aliens in Germany—in 1933 there were 66,606,000 inhabitants in the German Reich, of whom 499,682 (.75%) were Jews."