Philosophical pessimism is a family of philosophical views that assign a negative value to life or existence. Philosophical pessimists commonly argue that the world contains an empirical prevalence of pains over pleasures, that existence is ontologically or metaphysically adverse to living beings, and that life is fundamentally meaningless or without purpose. Philosophical pessimism is not a single coherent movement, but rather a loosely associated group of thinkers with similar ideas and a resemblance to each other. Their responses to the condition of life are widely varied. Philosophical pessimists usually do not advocate for suicide as a solution to the human predicament; though many favour the adoption of antinatalism, that is, non-procreation.

Definitions

The word pessimism comes from Latin pessimus, meaning "the worst".

Philosophers define the position in a variety of ways. In Pessimism: A History and a Criticism, James Sully describes the essence of philosophical pessimism as "the denial of happiness or the affirmation of life's inherent misery". Byron Simmons writes, "[p]essimism is, roughly, the view that life is not worth living". Frederick C. Beiser writes, "pessimism is the thesis that life is not worth living, that nothingness is better than being, or that it is worse to be than not be". According to Paul Prescott, it is the view that "the bad prevails over the good".

Olga Plümacher identifies two fundamental claims of philosophical pessimism: "The sum of displeasure outweighs the sum of pleasure" and "Consequently the non-being of the world would be better than its being". Ignacio L. Moya defines pessimism as a position that holds that the essence of existence can be known (at least partially); that life is essentially characterized by needs, wants, and pain, and hence suffering is inescapable; that there are no ultimate reasons for, no cosmic plan or purpose to suffering; and that, ultimately, non-existence is preferable to existence.

Themes

Reaching a pessimistic conclusion can be approached in various ways, with numerous arguments reinforcing this perspective. However, certain recurring themes consistently emerge:

- Life is not worth living — one of the most common arguments of pessimists is that life is not worth living. In short, pessimists view existence, overall, as having a deleterious effect on living beings: to be alive is to be put in a bad position.

- The bad prevails over the good — generally, the bad wins over the good. This can be understood in two ways. Firstly, one can make a case that — irrespective of the quantities of goods and evils — the suffering cannot be compensated for by the good. Secondly, one can make a case that there is a predominance of bad things over good things.

- Non-existence is preferable to existence — since existence is bad, it would have been better had it not have been. This point can be understood in one of the two following ways. Firstly, one can argue that, for any individual being, it would have been better had they never existed. Secondly, various pessimists have argued that the non-existence of the whole world would be better than its existence.

Development of pessimist thought

Pessimistic sentiments can be found throughout religions and in the works of various philosophers. The major developments in the tradition started with the works of German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, who was the first to provide an explanation for why there is so much misery in the world and construct a complete philosophical system in which pessimism played a major role.

Ancient times

One of the central points of Buddhism, which originated in ancient India, is the claim that life is full of suffering and unsatisfactoriness. This is known as dukkha from the Four Noble Truths.

In the Ecclesiastes from the Abrahamic religions, which originated in the Middle East, the author laments the meaninglessness of human life, views life as worse than death and expresses antinatalistic sentiments towards coming into existence. These views are made central in Gnosticism, a religious movement stemming from Christianity, where the body is seen as a type of a "prison" for the soul, and the world as a type of hell.

Hegesias of Cyrene, who lived in ancient Greece, argued that lasting happiness cannot be realized because of constant bodily ills and the impossibility of achieving all our goals.

19th century Germany

Arthur Schopenhauer was the first philosopher who constructed an entire philosophical system, where he presented an explanation of the world through metaphysics, aesthetics, epistemology, and ethics — all connected with a pessimistic view of the world. Schopenhauer viewed the world as having two sides — Will and representation. Will is pure striving, aimless, incessant, with no end; it is the inner essence of all things. Representation is how we view the world with our particular perceptual and cognitive endowment; it is how we build objects from our perceptions.

In living creatures, the Will takes the form of the will to life — self-preservation or the survival instinct appearing as striving to satisfy desires. And since this will to life is our inner nature, we are doomed to be always dissatisfied, as one satisfied desire makes room for striving for yet another thing. There is, however, something we can do with that ceaseless willing. We can take temporary respite during aesthetic contemplation or through cultivating a moral attitude. We can also defeat the will to life more permanently through asceticism, achieving equanimity.

Main arguments

The most common arguments for the tenets of philosophical pessimism are briefly presented here.

Duḥkha as the mark of existence

Constant dissatisfaction — duḥkha — is an intrinsic mark of all sentient existence. All living creatures have to undergo the sufferings of birth, aging, sickness and death; want what they do not have, avoid what they do not like, and feel loss for the positive things they have lost. All of these types of striving (taṇhā) are sources of suffering, and they are not external but are rather inherent vices (such as greed, lust, envy, self-indulgence) of all living creatures.

Since in Buddhism one of the central concepts is that of liberation or nirvana, this highlights the miserable character of existence, as there would be no need to make such a great effort to free oneself from a mere "less than ideal state". Since enlightenment is the goal of Buddhist practices through the Noble Eightfold Path, the value of life itself, under this perspective, appears as doubtful.

Pleasure doesn't add anything positive to our experience

A number of philosophers have put forward criticisms of pleasure, essentially denying that it adds anything positive to our well-being above the neutral state.

Pleasure as the mere removal of pain

A particular strand of criticism of pleasure goes as far back as to Plato, who said that most of the pleasures we experience are forms of relief from pain, and that the unwise confuse the neutral painless state with happiness. Epicurus pushed this idea to its limit and claimed that, "[t]he limit of the greatness of the pleasures is the removal of everything which can give pain". As such, according to Epicureans, one can not be better off than being free from pain, anxiety, distress, fear, irritation, regret, worry, etc. — in the state of tranquillity.

According to Knutsson, there are a couple of reasons why we might think that. Firstly, we can say that one experience is better than another by recognizing that the first one lacks a particular discomfort. And we can do that with any number of experiences, thus explaining what it means to feel better, all that just with relying on taking away disturbances. Secondly, it's difficult to find a particular quality of experience that would make it better than a completely undisturbed state. Thirdly, we can explain behavior without invoking positive pleasures. Fourthly, it's easy to understand what it means for an experience to have certain imperfections (aversive qualities), while it's not clear what it would mean for an experience to be genuinely better than neutral. And lastly, a model with only negative and neutral states is theoretically simpler than one containing an additional class of positive experiences.

No genuine positive states

A stronger version of this view is that there may be no states that are undisturbed or neutral. It's at least plausible that in every state we could notice some dissatisfactory quality such as tiredness, irritation, boredom, worry, feeling uncomfortable, etc. Instead of neutral states, there may simply be "default" states — states with recurrent but minor frustrations and discomforts that, over time, we got used to and learned not to do anything about. Pleasure as the mere relief from striving.

Schopenhauer maintained that only pain is positive. That is, only pain is directly felt — it's experienced as something which is immediately added to our consciousness. On the other hand, pleasure is only ever negative, which means it only takes away something already present in our experience — and thus is only experienced in an indirect or mediate way. He put forward his negativity thesis — that pleasure is only ever a relief from pain. Later German pessimists — Julius Bahnsen, Eduard von Hartmann, and Philipp Mainländer — held very similar views.

Pain can be removed in one of two ways. One way is to satisfy a desire. Since to strive is to suffer, once a desire is satisfied, suffering momentarily stops. The second way is through distraction. When we're not paying attention to what we lack — and hence, desire — we are temporarily at peace. This happens in cases of intellectual and aesthetic experiences.

A craving may arise when we direct our attention towards some external object, or when we notice something unwanted about our current situation. This is experienced as a visceral need to change something about the current state. When we do not feel any such cravings, we are content or tranquil — we feel no urgency or need to change anything about our experience.

No genuine counterpart to suffering

Alternatively, it can be argued that, for any purported pleasant state, we never find — under closer inspection — anything that would make it a positive or genuine counterpart to suffering. For an experience to be genuinely positive it would have to be an experiential opposite to suffering. However, it's difficult to understand what it would take for an experience to be an opposite of another experience — there just seem to be separate axes of experiences (hot and cold, loud and silent), which are noticed as contrasting. And even if we granted that the idea of an experiential opposite makes sense, it's difficult — if not impossible — to actually find a clear example of such an experience that would survive scrutiny. There is some neuroscientific evidence that positive and negative experiences are not laid on the same axis, but rather comprise two distinct — albeit interacting — systems.

Life contains uncompensated evils

One argument for the negative view on life is the recognition that evils are unconditionally unacceptable. A good life is not possible with evils in it. This line of thinking is based on Schopenhauer's statement that "the ill and evil in the world... even if they stood in the most just relation to each other, indeed even if they were far outweighed by the good, are nevertheless things that should absolutely never exist in any way, shape or form" in The World as Will and Representation. The idea here is that no good can ever erase the experienced evils, because they are of a different quality or kind of importance.

Schopenhauer elaborates on the vital difference between the good and the bad, saying that, "it is fundamentally beside the point to argue whether there is more good or evil in the world: for the very existence of evil already decides the matter since it can never be cancelled out by any good that might exist alongside or after it, and cannot therefore be counterbalanced", and adding that, "even if thousands had lived in happiness and delight, this would never annul the anxiety and tortured death of a single person; and my present wellbeing does just as little to undo my earlier suffering."

One way of interpreting the argument is by focusing on how one thing could compensate another. The goods can only compensate the evils, when they a) happen to the same subject, and b) happen at the same time. The reason why the good has to happen to the same subject is because the miserable cannot feel the happiness of the joyful, and hence it has no effect on him. The reason why the good has to happen at the same time is because the future joy does not act backwards in time, and so it has no effect on the present state of the suffering individual. But these conditions are not being met, and hence life is not worth living. Here, it doesn't matter whether there are any genuine positive pleasures, because since pleasures and pains are experientially separated, the evils are left unrepaid.

Another interpretation of the negativity thesis — that goods are merely negative in character — uses metaphors of debt and repayment, and crime and punishment. Here, merely ceasing an evil does not count as paying it off, just like stopping committing a crime does not amount to making amends for it. The bad can only be compensated by something positively good, just like a crime has to be answered for by some punishment, or a debt has to be paid off by something valuable. If the good is merely taking away an evil, then it cannot compensate for the bad since it's not of the appropriate kind — it's not a positive thing that could "repay the debt" of the bad.

Suffering is essential to life because of perpetual striving

Arthur Schopenhauer introduces an a priori argument for pessimism. The basis of the argument is the recognition that sentient organisms—animals—are embodied and inhabit specific niches in the environment. They struggle for their self-preservation. Striving to satisfy wants is the essence of all organic life.

Schopenhauer posits that striving is the essence of life. All striving, he argues, involves suffering. Thus, he concludes that suffering is unavoidable and inherent to existence. Given this, he says that the balance of good and bad is on the whole negative.

There are a couple of reasons why suffering is a fundamental aspect of life:

- Satisfaction is elusive: organisms strive towards various things all the time. Whenever they satisfy one desire, they want something else and the striving begins anew.

- Happiness is negative: while needs come to us seemingly out of themselves, we have to exert ourselves in order to experience some degree of joy. Moreover, pleasure is only ever a satisfaction—or elimination—of a particular desire. Therefore, it is only a negative experience as it temporarily takes away a striving or need.

- Striving is suffering: as long as striving is not satisfied, it's being experienced as suffering.

- Boredom is suffering: the lack of an object of desire is experienced as a discomforting state.

The terminality of human life

According to Julio Cabrera's ontology, human life has a structurally negative value. Under this view, human life does not provoke discomfort in humans due to the particular events that happen in the lives of each individual, but due to the very being or nature of human existence as such. The following characteristics constitute what Cabrera calls the "terminality of being" — in other words, its structurally negative value:

- The being acquired by a human at birth is decreasing (or "decaying"), in the sense of a being that begins to end since its very emergence, following a single and irreversible direction of deterioration and decline, of which complete consummation can occur at any moment between some minutes and around one hundred years.

- From the moment they come into being, humans are affected by three kinds of frictions: physical pain (in the form of illnesses, accidents, and natural catastrophes to which they are always exposed); discouragement (in the form of "lacking the will", or the "mood" or the "spirit", to continue to act, from mild taedium vitae to serious forms of depression), and finally, exposure to the aggressions of other humans (from gossip and slander to various forms of discrimination, persecution, and injustice); aggressions that we too can inflict on others (who are also submitted, like us, to the three kinds of friction).

- To defend themselves against (a) and (b), human beings are equipped with mechanisms of creation of positive values (ethical, aesthetic, religious, entertaining, recreational, as well as values contained in human realizations of all kinds), which humans must keep constantly active. All positive values that appear within human life are reactive and palliative; they do not arise from the structure of life itself, but are introduced by the permanent and anxious struggle against the decaying life and its three kinds of friction, with such struggle however doomed to be defeated, at any moment, by any of the mentioned frictions or by the progressive decline of one's being.

For Cabrera, this situation is further worsened by a phenomenon he calls "moral impediment", that is, the structural impossibility of acting in the world without harming or manipulating someone at some given moment. According to him, moral impediment happens not necessarily because of a moral fault in us, but due to the structural situation in which we have been placed. The positive values that are created in human life come into being within a narrow and anxious environment.

Human beings are cornered by the presence of their decaying bodies as well as pain and discouragement, in a complicated and holistic web of actions, in which we are forced to quickly understand diversified social situations and take relevant decisions. It is difficult for our urgent need to build our own positive values, not to end up harming the projects of other humans who are also anxiously trying to do the same, that is, build their own positive values. The asymmetry between harms and benefits

David Benatar

argues that there is a significant difference between lack/presence of

harms and benefits when comparing a situation when a person exists with a

situation when said person never exists. The starting point of the

argument is the following noncontroversial observation:

1. The presence of pain is bad.

2. The presence of pleasure is good.

However, the symmetry breaks when we consider the absence of pain and pleasure:

3. The absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone.

4. The absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is somebody for whom this absence is a deprivation.

Based on the above, Benatar infers the following:

- the absence of pain is better in the case where a person never exists than the presence of pain where a person does exist,

- the absence of pleasure is not worse in the case where a person never exists than the presence of pleasure where a person does exists.

In short, the absence of pain is good, while the absence of pleasure is not bad. From this it follows that not coming into existence has advantages over coming into existence for the one who would be affected by coming into the world. This is the cornerstone of his argument for antinatalism — the view that coming into existence is bad.

Empirical differences between the pleasures and pains in life

To support his case for pessimism, Benatar mentions a series of empirical differences between the pleasures and pains in life. In a strictly temporal aspect, the most intense pleasures that can be experienced are short-lived (e.g. orgasms), whereas the most severe pains can be much more enduring, lasting for days, months, and even years. The worst pains that can be experienced are also worse in quality or magnitude than the best pleasures are good, offering as an example the thought experiment of whether one would accept "an hour of the most delightful pleasures in exchange for an hour of the worst tortures".

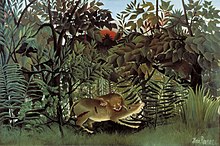

In addition to citing Schopenhauer, who made a similar argument, when asking his readers to "compare the feelings of an animal that is devouring another with those of that other"; the amount of time it may take for one's desires to be fulfilled, with some of our desires never being satisfied; the quickness with which one's body can be injured, damaged, or fall ill, and the comparative slowness of recovery, with full recovery sometimes never being attained the existence of chronic pain, but the comparative non-existence of chronic pleasure; the gradual and inevitable physical and mental decline to which every life is subjected through the process of ageing; the effortless way in which the bad things in life naturally come to us, and the efforts one needs to muster in order to ward them off and obtain the good things; the lack of a cosmic or transcendent meaning to human life as a whole, borrowing a term from Spinoza, according to Benatar our lives lack meaning from the perspective of the universe, that is, sub specie aeternitatis

Benatar concludes that, even if one argues that the bad things in life are in some sense necessary for human beings to appreciate the good things in life, or at least to appreciate them fully, he asserts that it is not clear that this appreciation requires as much bad as there is, and that our lives are worse than they would be if the bad things were not in such sense necessary.

Human life would be vastly better if pain were fleeting and pleasure protracted; if the pleasures were much better than the pains were bad; if it were really difficult to be injured or get sick; if recovery were swift when injury or illness did befall us; and if our desires were fulfilled instantly and if they did not give way to new desires. Human life would also be immensely better if we lived for many thousands of years in good health and if we were much wiser, cleverer, and morally better than we are.

Responses to the evils of existence

Pessimistic philosophers came up with a variety of ways of dealing with the suffering and misery of life.

Schopenhauer's renunciation of the will to life

Arthur Schopenhauer regarded his philosophy not only as a condemnation of existence, but also as a doctrine of salvation that allows one to counteract the suffering that comes from the will to life and attain tranquillity. According to Schopenhauer, suffering comes from willing (striving, desiring). One's willing is proportional to one's focus on oneself, one's needs, fears, individuality, etc. So, Schopenhauer reasons, to interrupt suffering, one has to interrupt willing. And to diminish willing, one has to diminish the focus on oneself. This can be accomplished in a couple of ways.

Aesthetic contemplation

Aesthetic contemplation is the focused appreciation of a piece of art, music, or even an idea. It is disinterested and impersonal. It is disinterested — one's interests give way to a devotion to the object; it's being considered as an end in itself. It is impersonal — not constrained by one's own likes and dislikes. Aesthetic appreciation evokes a universal idea of an object, rather than the perception of the object as unique.

During that time, one "loses oneself" in the object of contemplation, and the sense of individuation temporarily dissolves. This is because the universality of the object of contemplation passes onto the subject. One's consciousness becomes will-less. One becomes — if only for a brief moment — a neutral spectator or a "pure subject", unencumbered by one's own self, needs, and suffering.

Compassionate moral outlook

For Schopenhauer, a proper moral attitude towards others comes from the recognition that the separation between living beings occurs only in the realm of representation, originating from the principium individuationis. Underneath the representational realm, we are all one. Each person is, in fact, the same Will — only manifested through different objectifications. The suffering of another being is thus our own suffering. The recognition of this metaphysical truth allows one to attain a more universal, rather than individualistic, consciousness. In such a universal consciousness, one relinquishes one's exclusive focus on one's own well-being and woe towards that of all other beings.

Asceticism

Schopenhauer explains that one may go through a transformative experience in which one recognizes that the perception of the world as being constituted of separate things, that are impermanent and constantly striving, is illusory. This can come about through knowledge of the workings of the world or through an experience of extreme suffering. One sees through the veil of Maya. This means that one no longer identifies oneself as a separate individual. Rather, one recognizes himself as all things. One sees the source of all misery — the Will as the thing-in-itself, which is the kernel of all reality. One can then change one’s attitude to life towards that of the renunciation of the will to life and practice self-denial (not giving in to desires).

The person who attains this state of mind lives his life in complete peace and equanimity. He is not bothered by desires or lack. He accepts everything as it is.

This path of redemption, Schopenhauer argues, is more permanent, since it's grounded in a profound recognition that changes one's attitude. It's not merely a fleeting moment as in the case of an aesthetic experience.

The ascetic way of life, however, is not available for everyone — only a few rare and heroic individuals may be able to live as ascetics and attain such a state. More importantly, Schopenhauer explains, asceticism requires virtue; and virtue can be cultivated but not taught.

Defence mechanisms

Peter Wessel Zapffe viewed humans as animals with an overly developed consciousness who yearn for justice and meaning in a fundamentally meaningless and unjust universe — constantly struggling against feelings of existential dread as well as the knowledge of their own mortality. He identified four defence mechanisms that allow people to cope with disturbing thoughts about the nature of human existence:

Isolation: the troublesome facts of existence are simply repressed — they are not spoken about in public, and are not even thought about in private.

Anchoring: one fixates (anchors) oneself on cultural projects, religious beliefs, ideologies, etc.; and pursue goals appropriate to the objects of one's fixation. By dedicating oneself to a cause, one focuses one's attention on a specific value or ideal, thus achieving a communal or cultural sense of stability and safety from unsettling existential musings.

Distraction: through entertainment, career, status, etc., one distracts oneself from existentially disturbing thoughts. By constantly chasing for new pleasures, new goals, and new things to do, one is able to evade a direct confrontation against mankind's vulnerable and ill-fated situation in the cosmos.

Sublimation: artistic expression may act as a temporary means of respite from feelings of existential angst by transforming them into works of art that can be aesthetically appreciated from a distance.

Non-procreation and extinction

Concern for those who will be coming into this world has been present throughout the history of pessimism. Notably, Arthur Schopenhauer asked: One should try to imagine that the act of procreation were neither a need, nor accompanied by sexual pleasure, but instead a matter of pure, rational reflection; could the human race even continue to exist? Would not everyone, on the contrary, have so much compassion for the coming generation that he would rather spare it the burden of existence, or at least refuse to take it upon himself to cold-bloodedly impose it on them?

Schopenhauer also compares life to a debt that's being collected through urgent needs and torturing wants. We live by paying off the interests on this debt by constantly satisfying the desires of life; and the entirety of such debt is contracted in procreation: when we come into the world.

Anthropocentric antinatalism

Some pessimists, most notably Peter Wessel Zapffe and David Benatar, prescribe abstention from procreation as the best response to the ills of life. A person can only do so much to secure oneself from suffering or help others in need. The best course of action, they argue, is to not bring others into a world where discomfort is guaranteed.

They also suggest a scenario where humanity decides not to continue to exist, but instead chooses to go down the route of phased extinction. The resulting extinction of the human species would not be regrettable but a good thing. They go as far as to prescribe non-procreation as the morally right — or even obligatory — course of action. Zapffe conveys this position through the words of the titular Last Messiah: "Know yourselves – be infertile and let the earth be silent after ye".

Wildlife antinatalism

Antinatalism can be extended to animals. Benatar clearly notes that his "argument applies not only to humans but also to all other sentient beings" and that "coming into existence harms all sentient beings". He reinforces his view when discussing extinction by saying "it would be better, all things considered, if there were no more people (and indeed no more conscious life)."

It can be argued that since we have a prima facie obligation to help humans in need, and preventing future humans from coming into existence is helping them, and there is no justification for treating animals worse, we have a similar obligation to animals living in the wild. That is, we should also help alleviate their suffering and introduce certain interventions to prevent them from coming into the world — a position which would be called "wildlife anti-natalism".

Suicide

Some pessimists, including David Benatar and Julio Cabrera, argue that in some extreme situations, such as intense pain, terror, and slavery, people are morally justified to end their own lives. Although this will not resolve the human predicament, it may at the very least stop further suffering or moral degradation of the person in question. Cabrera says that dying is usually not pleasant nor dignified, so suicide is the only way to choose the way one dies. He writes, "If you want to die well, you must be the artist of your own death; nobody can replace you in that."

Arthur Schopenhauer rejects various objections to suicide stemming from religion, as well as those based on accusations of cowardice or insanity regarding the person who decides to end their own life. In this perspective, we should be compassionate towards the suicide — we should understand that someone may not be able to bear the sufferings present in their own life, and that one's own life is something that one has an indisputable right to.

Schopenhauer does not see suicide as a kind of solution to the sufferings of existence. His opposition to suicide is rooted in his metaphysical system. Schopenhauer focuses on human nature — which is governed by the Will. This means that we are in a never ending cycle of striving to achieve our ends, feeling dissatisfied, feeling bored, and once again desiring something else. Yet because the Will is the inner essence of existence, the source of our suffering is not exactly in us, but in the world itself.

Taking one's life is a mistake, for one still would like to live, but simply in better conditions. The suicidal person still desires goods in life — a "person who commits suicide stops living precisely because he cannot stop willing". It is not one's own individual life that is the source of one's suffering, but the Will, the ceaselessly striving nature of existence. The mistake is in annihilating an individual life, and not the Will itself. The Will cannot be negated by ending one's life, so it's not a solution to the sufferings embedded in existence itself.

David Benatar considers many objections against suicide, such as it being a violation of the sanctity of human life, a violation of the person's right to life, being unnatural, or being a cowardly act, to be unconvincing. The only relevant considerations that should be taken into account in the matter of suicide are those regarding people to whom we hold some special obligations. Such as, for example, our family members. In general, for Benatar the question of suicide is more a question of dealing with the particular miseries of one's life, rather than a moral problem per se. Consequently, he argues that, in certain situations, suicide is not only morally justified but is also a rational course of action.

Benatar's arguments regarding the poor quality of human life do not lead him to the conclusion that death is generally preferable to the continuation of life. But they do serve to clarify as to why there are cases in which one's continued existence would be worse than death, as they make it explicit that suicide is justified in a greater variety of situations than we would normally grant. Every person's situation is different, and the question of the rationality of suicide must be considered from the perspective of each particular individual — based on their own hardships and prospects regarding the future.

Jiwoon Hwang argued that the hedonistic interpretation of David Benatar's axiological asymmetry of harms and benefits entails promortalism — the view that it is always preferable to cease to exist than to continue to live. Hwang argues that the absence of pleasure is not bad in the following cases: for the one who never exists, for the one who exists, and for the one who ceased to exist. By "bad" we mean that it's not worse than the presence of pleasure for the one who exists. This is consistent with Benatar's statement that the presence of pleasure for the existing person is not an advantage over the absence of pleasure for the never existing and vice versa.

Collective ending of all life

Eduard von Hartmann was against all individualistic forms of abolition of suffering, prominent in Buddhism and in Schopenhauer's philosophy, since they leave the problem of suffering still going on for others. Instead, he opted for a collective solution: he believed that life progresses towards greater rationality—culminating in humankind—and that as humans became more educated and more intelligent, they would see through various illusions regarding the abolishion of suffering, eventually realizing that the problem lies ultimately in existence itself.

Thus, humanity as a whole would recognize that the only way to end the suffering present in life is to end life itself. This would happen in the future, where people would have advanced technologically to a point where they could destroy the whole of nature. That, for von Hartmann, would be the ultimate negation of the Will by Reason.

Pessimism and other philosophical topics

Animals

Aside from the human predicament, many philosophical pessimists also emphasize the negative quality of the life of non-human animals, criticizing the notion of nature as a "wise and benevolent" creator. In his 1973 Pulitzer Prize winning book The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker describes it thus:

What are we to make of a creation in which the routine activity is for organisms to be tearing others apart with teeth of all types—biting, grinding flesh, plant stalks, bones between molars, pushing the pulp greedily down the gullet with delight, incorporating its essence into one's own organization, and then excreting with foul stench and gasses the residue. Everyone reaching out to incorporate others who are edible to him. The mosquitoes bloating themselves on blood, the maggots, the killer-bees attacking with a fury and a demonism, sharks continuing to tear and swallow while their own innards are being torn out—not to mention the daily dismemberment and slaughter in "natural" accidents of all types (...) Creation is a nightmare spectacular taking place on a planet that has been soaked for hundreds of millions of years in the blood of all its creatures. The soberest conclusion that we could make about what has actually been taking place on the planet for about three billion years is that it is being turned into a vast pit of fertilizer. But the sun distracts our attention, always baking the blood dry, making things grow over it, and with its warmth giving the hope that comes with the organism's comfort and expansiveness.

The theory of evolution by natural selection can be said to justify a form of philosophical pessimism based on a negative evaluation of the lives of animals in the wild. In 1887, Charles Darwin expressed a feeling of revolt at the notion that God's benevolence is limited, stating: "for what advantage can there be in the sufferings of millions of the lower animals throughout almost endless time?" The animal activist and moral philosopher Oscar Horta argues that because of evolutionary processes, not only is suffering in nature inevitable, but that it actually prevails over happiness.

For evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, nature is in no way benevolent. He argues that what is at stake in biological processes is nothing more than the survival of DNA sequences of genes. Dawkins also asserts that as long as the DNA is transmitted, it does not matter how much suffering such transmission entails and that genes do not care about the amount of suffering they cause because nothing affects them emotionally. In other words, nature is indifferent to unhappiness, unless it has an impact on the survival of the DNA. Although Dawkins does not explicitly establish the prevalence of suffering over well-being, he considers unhappiness to be the "natural state" of wild animals:

The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive; others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear; others are being slowly devoured from within by rasping parasites; thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst and disease. It must be so. If there is ever a time of plenty, this very fact will automatically lead to an increase in population until the natural state of starvation and misery is restored. ... In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won't find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.

Abortion

Even though pessimists agree on the judgment that life is bad and some pessimistic antinatalists criticise procreation, their views on abortion differ.

Pro-death view

David Benatar holds a "pro-death" stance on abortion. He argues that in the earlier stages of pregnancy, when the fetus has not yet developed consciousness and has no morally relevant interests, we should adopt a presumption against carrying the fetus to term. What demands justification is not the act of abortion, but the failure to abort the fetus (in the early stages of pregnancy). Benatar does not argue that such early abortions should be mandatory, but only that it would be preferable to perform the abortion.

Anti-abortion view

Julio Cabrera

notices that abortion requires consideration of and action upon

something that is already there. He argues that we must take it into our

moral deliberations, regardless of the nature of that thing. He gives the following argument against abortion:

P1. From the perspective of negative ethics, it is wrong to eliminate another human being only for our benefit, hence treating him as an obstacle to be removed.

P2. It’s morally good to act in favor of those who cannot defend themselves.

P3. A fetus is something that begins to terminate from the very beginning, and it terminates as a human being.

P4. A human fetus is, within the context of gestation, pregnancy and birth, the most helpless being involved.

Conclusion: Therefore, from the perspective of negative ethics, it is morally wrong to eliminate (abort) a human being.

Cabrera further elaborates on the argument with a couple of points. Since we are all valueless, the victimizer has no greater value than the victim to justify the killing. It's better to err on the side of caution and not abort because it's difficult to say when a fetus becomes a human. A fetus has a potential to become a rational agent with consciousness, feelings, preferences, thoughts, etc. We can think of humans as beings who are always in self-construction; and a fetus is such a type of being. Furthermore, a fetus is — like any other human being — in a process of "decay". Finally, we should also debate the status of those who perform abortions and the women who undergo abortions; not just the status of the fetus.

Death

For Arthur Schopenhauer, every action (eating, sleeping, breathing, etc.) was a struggle against death, although one which always ends with death's triumph over the individual. Since other animals also fear death, the fear of death is not rational, but more akin to an instinct or a drive, which he called the will to life. In the end, however, death dissolves the individual and, with it, all fears, pains, and desires. Schopenhauer views death as a "great opportunity not to be I any longer". Our inner essence is not destroyed though — since we are a manifestation of the universal Will.

David Benatar has not only a negative view on coming into existence, but also on ceasing to exist. Even though it is a harm for us to come into existence, once we do exist we have an interest in continuing to exist. We have plans for the future; we want to achieve our goals; there may be some future goods we could benefit from, if we continue to exist. But death annihilates us; in this way robbing us from our future and the possibility of us realizing our plans.

Criticism

Plümacher's criticisms of Schopenhauer

Olga Plümacher criticizes Schopenhauer's system on a variety of points. According to Schopenhauer, an individual person is itself a manifestation of the Will. But if that is the case, then the negation of the Will is also an illusion, since if it were genuine, it would bring about the end of the world. Furthermore, she notices that for Schopenhauer, the non-existence of the world is preferable to its existence. However, this is not an absolute statement (that is, it says that the world is the worst), but a comparative statement (that is, it says that its worse than something else).

Against the claim that pleasures are only ever negative

A claim pessimists often make is that pleasures are negative in nature — they are mere satisfactions of desires or removals of pains. Some object to this by providing intuitive counterexamples, where we are engaged in something pleasurable which seems to be adding some genuine pleasure above the neutral state of undisturbness. This objection can be presented like this:

Imagine that I am enjoying the state of being hydrated, full and warm. Then somebody offers me a small chocolate bon-bon, and I greatly enjoy the delicious taste of the dark chocolate. Why am I not experiencing more pleasure now than I was before (...)?

The objection here is that we can clearly introspect that we feel something added to our experience, not that we merely no longer feel some pain, boredom, or desire. Such experiences include pleasant surprises, waking up in a good mood, savoring delicious meals, anticipating something good that will likely happen to us, and others.

The response to these objections from counterexamples can run as follows. Usually, we do not focus enough on our present state to notice all disturbances (discontentment). It's likely we could notice some disturbances had we paid enough attention — even in situations where we think we experience genuine pleasure. Thus, it's at least plausible that these seemingly positive states have various imperfections, and we are not, in fact, undisturbed; and, therefore, we are below the hedonic neutral state.

Influence outside philosophy

TV and cinema

The character of Rust Cohle in the first season of the television series True Detective is noted for expressing a philosophically pessimistic worldview; the creator of the series was inspired by the works of Thomas Ligotti, Emil Cioran, Eugene Thacker and David Benatar when creating the character.

Literature

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor (1864). Notes from Underground

- Le Guin, Ursula K. (1973). The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas

- Leopardi, Giacomo (1835). Canti

- Ligotti, Thomas (2018). The Conspiracy Against the Human Race: A Contrivance of Horror. Penguin Books ISBN 978-0143133148

- McCarthy, Cormac (1992/1985). Blood Meridian; or, The Evening Redness in the West. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group ISBN 978-0679728757

- McCarthy, Cormac (2006). The Road. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group ISBN 978-0307387899

- Pessoa, Fernando (1982). The Book of Disquiet

- Thacker, Eugene (2018). Infinite Resignation. Repeater ISBN 978-1912248193

- Thomson, James "B.V." (1874). The City of Dreadful Night

- Yalom, Irvin D. (2005). The Schopenhauer Cure. HarperCollins ISBN 978-0-06-093810-9 (The novel switches between the current events happening around a therapy group and the psychobiography of Arthur Schopenhauer).

- Voltaire (1759). Candide

- Novels and short stories by Guy de Maupassant.

- Labadie, Laurance (2014). Anarcho-Pessimism: the collected writings of Laurance Labadie. Ardent Press.

- Andreyev, Leonid (1906). Lazarus