Cover of SDS pamphlet c. 1966 | |

| Predecessor | Student League for Industrial Democracy |

|---|---|

| Successor | New Students for a Democratic Society |

| Formation | 1960 |

| Founded at | Ann Arbor, Michigan |

| Dissolved | 1974 |

| Purpose | Left-wing student activism |

| Location | |

| Secessions | New American Movement Revolutionary Youth Movement Weather Underground |

| Affiliations | Venceremos Brigade |

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Students' rights |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships and parliamentary procedure, the founders conceived of the organization as a broad exercise in "participatory democracy". From its launch in 1960 it grew rapidly in the course of the tumultuous decade with over 300 campus chapters and 30,000 supporters recorded nationwide by its last national convention in 1969. The organization splintered at that convention amidst rivalry between factions seeking to impose national leadership and direction, and disputing "revolutionary" positions on, among other issues, the Vietnam War and Black Power.

A new national network for left-wing student organizing, also calling itself Students for a Democratic Society, was founded in 2006.

History

1960–1962: The Port Huron Statement

SDS developed from the youth branch of a socialist educational organization known as the League for Industrial Democracy (LID). LID itself descended from an older student organization, the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, founded in 1905 by Upton Sinclair, Walter Lippmann, Clarence Darrow, and Jack London. Early in 1960, to broaden the scope for recruitment beyond labor issues, the Student League for Industrial Democracy was reconstituted as SDS. They held their first meeting in 1960 on the University of Michigan campus at Ann Arbor, where Alan Haber was elected president. The SDS manifesto, known as the Port Huron Statement, was adopted at the organization's first convention in June 1962, based on an earlier draft by staff member Tom Hayden. Under Walter Reuther's leadership, the UAW paid for a range of expenses for the 1962 convention, including use of the UAW summer retreat in Port Huron.

The Port Huron Statement decried what it described as "disturbing paradoxes": that the world's "wealthiest and strongest country" should "tolerate anarchy as a major principle of international conduct"; that it should allow "the declaration 'all men are created equal...'" to ring "hollow before the facts of Negro life"; that, even as technology creates "new forms of social organization", it should continue to impose "meaningless work and idleness"; and with two-thirds of mankind undernourished that its "upper classes" should "revel amidst superfluous abundance".

In searching for "the spark and engine of change" the authors disclaimed any "formulas" or "closed theories". Instead, "matured" by "the horrors of a century" in which "to be idealistic is to be considered apocalyptic", Students for a Democratic Society would seek a "new left ... committed to deliberativeness, honesty [and] reflection."

The Statement proposed the university, with its "accessibility to knowledge" and an "internal openness", as a "base" from which students would "look outwards to the less exotic but more lasting struggles for justice." "The bridge to political power" would be "built through genuine cooperation, locally, nationally, and internationally, between a new left of young people and an awakening community of allies." It was to "stimulating this kind of social movement, this kind of vision and program in campus and community across the country" that the SDS were committed.

For the sponsoring League for Industrial Democracy there was an immediate issue. The Statement omitted the LID's standard denunciation of communism: the regret it expressed at the "perversion of the older left by Stalinism" was too discriminating, and its references to Cold War tensions too even handed. Hayden, who had succeeded Haber as SDS president, was called to a meeting where, refusing any further concession, he clashed with Michael Harrington (as he later would with Irving Howe).

As security against "a united-front style takeover of its youth arm" the LID had inserted a communist-exclusion clause in the SDS constitution. When in 1965 those who considered this too obvious a concession to the Cold-War doctrines of the right succeeded in removing the language, there was a final parting of the ways. The students' tie to their parent organization was severed by mutual agreement.

In drafting the Port Huron Statement, Hayden acknowledged the influence of a Bowdoin-College German-exchange student, Michael Vester. He encouraged Hayden to be more explicit about the contradictions "between political democracy and economic concentration of power", and to take a more international perspective. Vester was to be the first of a number of close connections between the American SDS and the West German SDS (Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund), a student movement that was to follow a similar trajectory.

1962–1964: Organize your own

In the academic year 1962–1963, the President was Hayden, the Vice President was Paul Booth, and the National Secretary was Jim Monsonis. There were nine chapters with, at most, about 1000 members. The National Office (NO) in New York City consisted of a few desks, some broken chairs, a couple of file cabinets and a few typewriters. As a student group with a strong belief in decentralization and a distrust for most organizations, the SDS had not developed, and was never to develop, a strong central directorate. National Office staffers worked long hours for little pay to service the local chapters, and to help establish new ones. Following the lead of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), most activity was oriented toward the civil rights struggle.

By the end of the academic year, there were over 200 delegates at the annual convention at Pine Hill, New York, from 32 different colleges and universities. The convention chose a confederal structure. Policy and direction would be discussed in a quarterly conclave of chapter delegates, the National Council. National officers, in the spirit of "participatory democracy", would be selected annually by consensus. Lee Webb of Boston University was chosen as National Secretary, and Todd Gitlin of Harvard University was made president.

In 1963 "racial equality" remained the cause celebre. In November 1963, the Swarthmore College chapter of SDS partnered with Stanley Branche and local parents to create the Committee for Freedom Now which led the Chester school protests along with the NAACP in Chester, Pennsylvania. From November 1963 through April 1964, the demonstrations focused on ending the de facto segregation that resulted in the racial categorization of Chester public schools, even after the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka. The racial unrest and civil rights protests made Chester one of the key battlegrounds of the civil rights movement.

However, within the Congress of Racial Equality, and within the SNCC (particularly after the 1964 Freedom Summer), there was the suggestion that white activists might better advance the cause of civil rights by organising "their own". At the same time, for many, 1963–64 was the academic year in which white poverty was discovered. Michael Harrington's The Other America "was the rage".

Conceived in part as a response to the gathering danger of a "white backlash," and with $5,000 from United Automobile Workers, Tom Hayden promoted an Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP). SDS community organizers would help draw neighbourhoods, both black and white, into an "interracial movement of the poor". By the end of 1964 ERAP had ten inner-city projects engaging 125 student volunteers.

Ralph Helstein, president of the United Packinghouse Workers of America, arranged for Hayden and Gitlin to meet with Saul Alinsky who, with twenty-five years experience in Chicago and across the country, was the acknowledged father of community organizing. To Helstein's dismay Alinsky dismissed the SDSers' venture into the field as naive and doomed to failure. Their view of the poor and of what could be achieved by consensus was absurdly romantic. Placing a premium on strong local leadership, structure and accountability, Alinsky's "citizen participation" was something "fundamentally different" from the "participatory democracy" envisaged by Hayden and Gitlin.

With the election of new leadership at the July 1964 national SDS convention there was already dissension. With the "whole balance of the organisation shifted to ERAP headquarters in Ann Arbor", the new National Secretary, C. Clark Kissinger cautioned against "the temptation to 'take one generation of campus leadership and run!' We must instead look toward building the campus base as the wellspring of our student movement." Gitlin's successor as president, Paul Potter, was blunter. The emphasis on "the problems of the dispossessed" had been misplaced: "It is through the experience of the middle class and the anesthetic of bureaucracy and mass society that the vision and program of participatory democracy will come—if it is to come."

Hayden, who committed himself to community organizing in Newark (there to witness the "race riots" in 1967) later suggested that if ERAP failed to build to greater success it was because of the escalating U.S. commitment in Vietnam: "Once again the government met an internal crisis by starting an external crisis." Yet there were ERAP volunteers more than ready to leave their storefront offices and heed the anti-war call to return to campus. Tending to the "less exotic struggles" of the urban poor had been a dispiriting experience.

However much the volunteers might talk at night about "transforming the system", "building alternative institutions," and "revolutionary potential", credibility on the doorstep rested on their ability to secure concessions from, and thus to develop relations with, the local power structures. Regardless of the agenda (welfare checks, rent, day-care, police harassment, garbage pick-up) the daytime reality was of delivery built "around all the shoddy instruments of the state." ERAP had seemed to trap the SDSers in "a politics of adjustment".

Lyndon B. Johnson's landslide in the November 1964 presidential election swamped considerations of Democratic-primary, or independent candidature, interventions—a path that had been tentatively explored in a Political Education Project. Local chapters expanded activity across a range of projects, including University reform, community-university relations, and were beginning to focus on the issue of the draft and Vietnam War. They did so within the confines of university bans on on-campus political organization and activity.

While students at Kent State, Ohio, had been protesting for the right to organize politically on campus a full year before, it is the televised birth of the Free Speech Movement at the University of California, Berkeley that is generally recognized as the first major challenge to campus governance. On October 1, 1964, crowds of upwards of three thousand students surrounded a police cruiser holding a student arrested for setting up an informational card table for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The sit-down prevented the car from moving for 32 hours. By the end of the year, demonstrations, meetings and strikes all but shut the university down. Hundreds of students were arrested.

1965–1966: Free Universities, and the Draft

In February 1965, President Johnson dramatically escalated the war in Vietnam. He ordered the bombing of North Vietnam (Operation Flaming Dart) and committed ground troops to fight the Viet Cong in the South. Campus chapters of SDS all over the country started to lead small, localized demonstrations against the war. On April 17 the National Office coordinated a march in Washington. Co-sponsored by Women Strike for Peace, and with endorsements from nearly all of the other peace groups, 25,000 attended. The first teach-in against the war was held in the University of Michigan, followed by hundreds more across the country. The SDS became recognized nationally as the leading student group against the war.

The National Convention in Akron (which FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover reported was attended by "practically every subversive organization in the United States") selected as President Carl Oglesby (Antioch College). He had come to SDSers' attention with an article against the war, written while he had been working for a defense contractor. The Vice President was Jeff Shero from the increasingly influential University of Texas chapter in Austin. Consensus, however, was not reached on a national program.

At the September National Council meeting "an entire cacophony of strategies was put forward" on what had clearly become the central issue, Vietnam. Some urged negotiation, others immediate U.S. withdrawal, still others Viet-Cong victory. "Some wanted to emphasize the moral horror of the war, others concentrated on its illegality, a number argued that it took funds away from domestic needs, and a few even then saw it as an example of 'American imperialism'. This was Oglesby's developing position. Thereafter, on November 27, at an anti-war demonstration in Washington, when Oglesby suggested that U.S. policy in Vietnam was essentially imperialist, and then called for an immediate ceasefire, he was wildly applauded and nationally reported.

The new, more radical, and uncompromising anti-war profile this suggested, appeared to drive the growth in membership. The influx discomfited older members like Todd Gitlin who, as he later conceded, simply had no "feel" for an anti-war movement. No consensus was reached as to what role the SDS should play in stopping the war. A final attempt by the old guard at a "rethinking conference" to establish a coherent new direction for the organization failed. The conference, held on the University of Illinois campus at Champaign-Urbana over Christmas vacation, 1965, was attended by about 360 people from 66 chapters, many of whom were new to SDS. Despite a great deal of discussion, no substantial decisions were made.

SDS chapters continued to use the draft as a rallying issue. Over the rest of the academic year, with the universities supplying the Selective Service Boards with class ranking, SDS began to attack university complicity in the war. The University of Chicago's administration building was taken over in a three-day sit-in in May. "Rank protests" and sit-ins spread to many other universities. The war, however, was not the only issue driving the newfound militancy. There were new and growing calls to seriously question a college experience that the Port Huron Statement had described as "hardly distinguishable from that of any other communications channel—say, a television set." Students were to start taking responsibility for their own education.

By the fall of 1965, largely under SDS impetus, there were several "free universities" in operation: in Berkeley, SDS reopened the New School offering "'Marx and Freud,' 'A Radical Approach to Science,' 'Agencies of Social Change and the New Movements'; in Gainesville, a Free University of Florida was established, and even incorporated; in New York, a Free University was begun in Greenwich Village, offering no fewer than forty-four courses ('Marxist Approaches to the Avant-garde Arts', 'Ethics and Revolution', 'Life in Mainland China Today'); and in Chicago, something called simply The School began with ten courses ('Neighborhood Organization and Nonviolence', 'Purposes of Revolution'). By the end of 1966 there were perhaps fifteen. Universities understood the challenge, and soon began to offer seminars run on similar student-responsive lines, beginning what SDSers saw as a "liberal swallow-up".

The summer convention of 1966 was moved farther west, to Clear Lake, Iowa. Nick Egleson was chosen as president, and Carl Davidson was elected vice president. Jane Adams, former Mississippi Freedom Summer volunteer and SDS campus traveler in Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, and Missouri, was elected Interim National Secretary. That fall, her companion Greg Calvert, recently a History Instructor at Iowa State University, became National Secretary. The convention marked a further turn towards organization around campus issues by local chapters, with the National Office cast in a strictly supporting role. Campus issues ranged from bad food, powerless student "governments", various in loco parentis manifestations, on-campus recruiting for the military and, again, ranking for the draft.

Despite the absence of a politically effective campus SDS chapter, Berkeley again became a center of particularly dramatic radical upheaval over the university's repressive anti-free-speech actions. One description of the convening of an enthusiastically supported student strike suggests the distance travelled from both the Left, and the civil rights, roots of earlier activism. Over "a sea of cheering bodies" before the Union building a twenty-foot banner proclaimed "Happiness Is Student Power". A booming address announced:

We're giving notice today, all of us, that we reject the notion that we should be patient and work for gradual change. That's the old way. We don't need the Old Left. We don't need their ideology or the working class, those mythical masses who are supposed to rise up and break their chains. The working class in this country is moving to the right. Students are going to be the revolutionary force in this country. Students are going to make the revolution because we have the will.

After a three-hour open mike meeting in the Life Sciences building, instead of closing with the civil-rights anthem "We Shall Overcome", the crowd "grabbed hands and sang the chorus to 'Yellow Submarine'".

SDSers understanding of their "own" was increasingly colored by the country's exploding countercultural scene. There were explorations—some earnest, some playful—of the anarchist or libertarian implications of the commitment to participatory democracy. At the large and active University of Texas chapter in Austin, The Rag, an underground newspaper founded by SDS leaders Thorne Dreyer and Carol Neiman has been described as the first underground paper in the country to incorporate the "participatory democracy, community organizing and synthesis of politics and culture that the New Left of the midsixties was trying to develop."

Inspired by a leaflet distributed by some poets in San Francisco, and organized by the Rag and the SDS in the belief that "there is nothing wrong with fun", a "Gentle Thursday" event in the fall of 1966 drew hundreds of area residents, bringing kids, dogs, balloons, picnics and music, to the UT West Mall. A summary ban by the UT administration ensured an even bigger, more enthusiastic, turnout for the second Gentle Thursday in the spring of 1967. Part of "Flipped Out Week", organized in coordination with a national mobilization against the war, it was a more defiant and overtly political affair. It included appearances by Stokley Carmichael, beat-poet Allen Ginsberg, and anti-war protests at the Texas State Capitol during a visit by Vice-President Hubert Humphrey. The example set a precedent for campus events across the country.

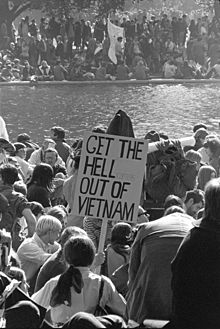

1967–1968: Stop the War

The winter and spring of 1967 saw an escalation in the militancy of campus protests. Demonstrations against military-contractors and other campus recruiters were widespread, and ranking and the draft issues grew in scale. The school year had started with a large demonstration against Dow Chemical Company recruitment at the University of Wisconsin in Madison on October 17. Peaceful at first, the demonstrations turned to a sit-in that was violently dispersed by the Madison police and riot squad, resulting in many injuries and arrests. A mass rally and a student strike then closed the university for several days. A nationwide coordinated series of demonstrations against the draft led by members of the Resistance, the War Resisters League, and SDS added fuel to the fire of protest. After conventional civil rights tactics of peaceful pickets seemed to have failed, the Oakland, California, Stop the Draft Week ended in mass hit and run skirmishes with the police. The huge (100,000 people) October 21 March on the Pentagon saw hundreds arrested and injured. Night-time raids on draft offices began to spread.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), mainly through its secret COINTELPRO (COunter INTELligence PROgram) and other law enforcement agencies were often exposed as having spies and informers in the chapters. FBI Director Hoover's general COINTELPRO directive was for agents to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize" the activities and leadership of the movements they infiltrated.

The National Office sought to provide greater coordination and direction (partly through New Left Notes, its weekly correspondence with the membership). In the spring of 1968, National SDS activists led an effort on the campuses called "Ten Days of Resistance" and local chapters cooperated with the Student Mobilization Committee in rallies, marches, sit-ins and teach-ins, and on April 18 in a one-day strike. About a million students stayed away from classes that day, the largest student strike to date. But it was the student shutdown of Columbia University in New York that commanded the national media. Led by an inter-racial alliance of Columbia SDS chapter activists and Student Afro Society activists, it helped make the SDS a household name. Membership again soared in the 1968–69 academic year.

More important for thinking within the National Office, Columbia and the outbreak of student protest which it symbolized seemed proof that "long months of SDS work were paying off." As targets students were "picking war, complicity, and racism, rather than dress codes and dorm hours, and as tactics sit-ins and takeovers, rather than petitions and pickets." Yet Congressional investigation was to find that most chapters continued to follow their own, rather than a national, agenda. In the fall of 1968 their issues fell into one or more of four broad categories: (1) war-related issues such as opposition to ROTC, military or CIA recruitment, and military research, on campus; (2) student power issues including requests for a pass-fail grading system, beer sales on campus, no dormitory curfews, and a student voice in faculty hiring; (3) support for university employees; and (4) support for black students.

The December 1967 convention took down what little suggestion there was of hierarchy within the structure of the organisation: it eliminated the Presidential and Vice-Presidential offices. They were replaced with a National Secretary (20-year-old Mike Spiegel), an Education Secretary (Texan Bob Pardun of the Austin chapter), and an Inter-organizational Secretary (former VP Carl Davidson). A clear direction for a national program was not set but delegates did manage to pass strong resolutions on the draft, resistance within the Army itself, and for an immediate withdrawal from Vietnam.

Women and SDS

There was no women's-equality plank in the Port Huron Statement. Tom Hayden had started drafting the statement from a jail cell in Albany, Georgia, where he landed on a Freedom Ride organized by Sandra "Casey" Cason (Casey Hayden). It is Cason that had first led Hayden into the SDS in 1960. Although herself regarded as "one of the boys", her recollection of those early SDS meetings is of interminable debate driven by young male intellectual posturing and, if a woman commented, of being made to feel as if a child had spoken among adults. (In 1962, she left Ann Arbor, and Tom Hayden, to return to the SNCC in Atlanta).

Seeking the "roots of the women's liberation movement" in the New Left, Sara Evans argues that in Hayden's ERAP program this presumption of male agency had been one of the undeclared sources of tension. Confronted with the reality of a war-heated economy, in which the only unemployed men "left to organize were very unstable and unskilled, winos, and street youth," the SDSers were disconcerted to find themselves having to organize around "nitty-gritty issues"—welfare, healthcare, childcare, garbage collection—springing "in cultural terms ... from the women's sphere of home and community life." Sexism was acknowledged as commonplace in the anti-war and New Left movement.

In December 1965, the SDS held a "rethinking conference" at the University of Illinois. One of the papers included in the conference packet, was a memo Casey Hayden and others had written the previous year for a similar SNCC event, and published the previous month in Liberation, the bi-monthly of the War Resisters League, under the title "Sex and Caste". As "the final impetus" for organizing a "women's workshop," Evans suggest it was "the real embryo of the new feminist revolt." But this was a revolt that was to play out largely outside of the SDS.

When, at the 1966 SDS convention, women called for debate they were showered with abuse, pelted with tomatoes. The following year there seemed to be a willingness to make some amends. The Women's Liberation Workshop succeeded in having a resolution accepted that insisted that women be freed "to participate in other meaningful activities" and that their "brothers" be relieved of "the burden of male chauvinism". The SDS committed to the creation of communal childcare centers, women's control over reproduction, the sharing of domestic work and, critically for an organization whose offices were almost entirely populated by men, to women participating at every level of the SDS "from licking stamps to assuming leadership positions." However, when the resolution was printed in the NO's New Left Notes it was with a caricature of a woman dressed in a baby-doll dress, holding a sign "We want our rights and we want them now!"

Little changed in the two years that followed. By and large the issues that were spurring the growth of an autonomous women's liberation movement were not considered relevant for discussion by SDS men or women (and if they were discussed, one prominent activist recalls, "separatism" had to be denounced "every five minutes"). Over the five tumultuous days of the final convention in June 1969 women were given just three hours to caucus and their call on women to struggle against their oppression was rejected. Inasmuch as women felt both empowered and thwarted in the movement, Todd Gitlin was later to claim some credit for SDS in engendering second-wave feminism. Women had gained skills and experience in organising but had been made to feel keenly their second-class status.

Secession and polarization

At the 1967 convention in Ann Arbor there was another, perhaps equally portentous, demand for equality and autonomy. Despite the winding down of SDS leadership support for ERAP, in some community projects struggles against inequality, racism and police brutality had taken on a momentum of their own. The projects had drawn in white working class activists. While open in acknowledging the debt they believed they owed to SNCC and to the Black Panthers, many were conscious that their poor white, and in some cases southern, backgrounds had limited their acceptance in "the Movement". In a blistering address, Peggy Terry announced that she and her neighbors in uptown, "Hillbilly Harlem", Chicago, had ordered student volunteers out of their community union. They would be relying on themselves, doing their own talking, and working only with those outsiders willing live as part of the community, and of "the working class", for the long haul.

With what she regarded as an implicit understanding for Stokely Carmichael's call for black people to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations, Terry argued that "the time has come for us to turn to our own people, poor and working-class whites, for direction, support, and inspiration, to organize around our own identity, our own interests."

Yet as Peggy Terry was declaring her independence from the SDS as a working-class militant, the most strident voices at the convention were of those who, jettisoning the reservations of the Port Huron old guard, were declaring the working class as, after all, the only force capable of subverting U.S. imperialism and of effecting real change. It was on the basis of this new Marxist polemic that endorsements were withheld from the mass demonstrations called by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam to coincide with the August 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

In the event, under a mandate to recruit and to offer support should the Chicago police "start rioting" (which they did), national SDSers were present. On August 28 national secretary Michael Klonsky was on Havana radio: "We have been fighting in the streets for four days. Many of our people have been beaten up, and many of them are in jail, but we are winning." But at the first national council meeting after the convention (University of Colorado, Boulder, October 11–13), the Worker Student Alliance had their line confirmed: attempts to influence political parties in the United States fostered an "illusion" that people can have democratic power over system institutions. The correct answer was to organize people in "direct action". "The 'center' has proven its failure ... it remains to the left not to cling to liberal myths but to build its own strength out of the polarization, to build the left 'pole'".

1969–1970: splintering and dissolution

The Worker Student Alliance (WSA) was a front organization for the Progressive Labor Party (PLP), whose delegates had first been seated in the 1966 SDS convention. The PLP was Maoist but was sufficiently old-school that it viewed policy and action not only from the perspective of class, but also from the perspective of "the class". The PLP condemned the protest in Chicago not only because there had been the "illusion" that the system could be effectively pressured or lobbied, but because, in their view, the "wild-in-the-streets" resistance estranged "the working masses" and made it more difficult for the left to build a popular base. It was an injunction that the PLP appeared to carry across a range of what they regarded as the wilder, or for the working man more challenging, expressions of the movement. These included feminists (those who want to "organize women to discuss their personal problems about their boyfriends"), the counterculture, and long hair.

At a time when the New Left Notes could describe the SDS as "a confederation of localized conglomerations of people held together by one name", and as events in the country continued to drift, what the PLP-WSA offered was the promise of organizational discipline and of a consistent vision. But there was a rival bid for direction and control of the organization.

At a national council held at the close of 1968 in Ann Arbor (attended by representatives of 100 of the reputed 300 chapters), a majority of national leadership and regional staffs pushed through a policy resolution written by national secretary Michael Klonsky titled "Toward a revolutionary youth movement". The SDS would transform itself into a revolutionary movement, reaching beyond the campus to find new recruits among young workers, high school students, the Armed Forces, community colleges, trade schools, drops outs, and the unemployed.

Like the PLP-WSA, this Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM) faction was committed to an anti-capitalist analysis that privileged the working class. But RYM made at least two concessions to the broader spirit of the times. First it outbid the PLP-WSA in accommodating black and ethnic mobilization by embracing the legitimacy within "the class" of "Third World nationalisms". "Oppressed colonies" in the United States had the right "to self-determination (including the right to political secession if they desire it)." Second, as a youth movement, the RYM allowed that—if only in solidarity with others of their generation—students could have some agency.

Yet neither tendency was an open house to incoming freshmen or juniors awakening to the possibilities for political engagement. Sale observes that "at a time when many young people wanted some explanations for the failure of electoral politics, SDS was led by people who had long since given up caring about elections and were trying to organize for revolution." To students "just beginning to be aware of their own radicalization and their potential role as the intelligentsia in an American left", the SDS was proposing that the "only really important agents for social change were the industrial workers, or the ghetto blacks, or the Third World revolutionaries." For students willing to "take on their [college] administrations for any number of grievances," SDS analysis emphasized "'de-studentizing', dropping out, and destroying universities." To those seeking to "supplant the tattered theories of corporate liberalism, SDS had only the imperfectly fashioned tenets of a borrowed Marxism and an untransmittable attachment to the theories of other revolutionaries".

As for women wishing to approach the SDS with their own issues, the RYM faction was scarcely more willing than the PLP-WSA to accord them space. At a time when young people in the Black Panthers were under vicious attack, they deemed it positively racist for educated white women to focus on their own oppression.

The Port Huron vision of the university as a place where, as "an adjunct" to the academic life, political action could be held open to "reason", and the Gentle Thursday openness to a range of expression, had been cast by the new revolutionary polemic onto "the junk heap of history".

In the new year the WSA and RYM began to split national offices and some chapters. Matters came to a head in the summer of 1969, at the SDS's ninth national convention held at the Chicago Coliseum. The two groups battled for control of the organization throughout the convention. The RYM and the National Office faction, led by Bernardine Dohrn, finally walked several hundred people out of the Colosseum.

This NO-RYM grouping reconvened themselves as the official convention near the National Office. They elected officers and they expelled the PLP. The charge was twofold: (1) "The PLP has attacked every revolutionary national struggle of the black and Latin American peoples in the U.S. as being racist and reactionary", and (2) the "PLP attacked Ho Chi Minh, the NLF, the revolutionary government of Cuba—all leaders of the people's struggles for freedom against U.S. imperialism."

The 500–600 people remaining in the meeting hall, dominated by PLP, declared itself the "Real SDS", electing PLP and WSA members as officers. By the next day, there were in effect two SDS organizations, "SDS-RYM" and "SDS-WSA."

SDS-RYM broke up soon after the split. In a decision to effectively dissolve the organization ("marches and protests won't do it"), a faction including Dohrn resolved upon armed resistance. In alliance with "the Black Liberation Movement", a "white fighting force" would "bring the war home" On October 6, 1969, the Weathermen planted their first bomb, blowing up a statue in Chicago commemorating police officers killed during the 1886 Haymarket Riot. Others were to follow Michael Klonsky into the New Communist Movement.

After the break-up of its rival and before dissolving in 1974 into the Committee Against Racism, the WSA continued on campuses as "the SDS". Functioning to recruit for PLP, it was a centralized, disciplined organization quite distinct from the original Port Huron movement.

New SDS

Beginning January 2006, a movement to revive the Students for a Democratic Society took shape. Two high school students, Jessica Rapchik and Pat Korte, decided to reach out to former members of the "Sixties" SDS (including Alan Haber, the organization's first president) and to build a new generation SDS. The new SDS held their first national convention in August 2006 at the University of Chicago. They describe themselves as a "progressive organization of student activists" intent on building "a strong student movement to defend our rights to education and stand up against budget cuts," to "oppose racism, sexism, and homophobia on campus" and to "say NO to war". They report chapters in 25 states with some thousands of supporters.