Reproductive rights rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. They also include the right of all to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence.

Reproductive rights may include some or all of the following: right to abortion; birth control; freedom from coerced sterilization and contraception; the right to access good-quality reproductive healthcare; and the right to education and access in order to make free and informed reproductive choices. Reproductive rights may also include the right to receive education about sexually transmitted infections and other aspects of sexuality, right to menstrual health and protection from practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM).

Reproductive rights began to develop as a subset of human rights at the United Nation's 1968 International Conference on Human Rights. The resulting non-binding Proclamation of Tehran was the first international document to recognize one of these rights when it stated that: "Parents have a basic human right to determine freely and responsibly the number and the spacing of their children." Women's sexual, gynecological, and mental health issues were not a priority of the United Nations until its Decade of Women (1975–1985) brought them to the forefront. States, though, have been slow in incorporating these rights in internationally legally binding instruments. Thus, while some of these rights have already been recognized in hard law, that is, in legally binding international human rights instruments, others have been mentioned only in non binding recommendations and, therefore, have at best the status of soft law in international law, while a further group is yet to be accepted by the international community and therefore remains at the level of advocacy.

Issues related to reproductive rights are some of the most vigorously contested rights' issues worldwide, regardless of the population's socioeconomic level, religion or culture.

The issue of reproductive rights is frequently presented as being of vital importance in discussions and articles by population concern organizations such as Population Matters.

Reproductive rights are a subset of sexual and reproductive health and rights.

History

Proclamation of Tehran

In 1945, the United Nations Charter included the obligation "to promote... universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without discrimination as to race, sex, language, or religion". However, the Charter did not define these rights. Three years later, the UN adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the first international legal document to delineate human rights; the UDHR does not mention reproductive rights. Reproductive rights began to appear as a subset of human rights in the 1968 Proclamation of Tehran, which states: "Parents have a basic human right to determine freely and responsibly the number and the spacing of their children".

This right was affirmed by the UN General Assembly in the 1969 Declaration on Social Progress and Development which states "The family as a basic unit of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all its members, particularly children and youth, should be assisted and protected so that it may fully assume its responsibilities within the community. Parents have the exclusive right to determine freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children." The 1975 UN International Women's Year Conference echoed the Proclamation of Tehran.

Cairo Programme of Action

The twenty-year "Cairo Programme of Action" was adopted in 1994 at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo. The non-binding Programme of Action asserted that governments have a responsibility to meet individuals' reproductive needs, rather than demographic targets. It recommended that family planning services be provided in the context of other reproductive health services, including services for healthy and safe childbirth, care for sexually transmitted infections, and post-abortion care. The ICPD also addressed issues such as violence against women, sex trafficking, and adolescent health. The Cairo Program is the first international policy document to define reproductive health, stating:

Reproductive health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and its functions and processes. Reproductive health therefore implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so. Implicit in this last condition are the right of men and women to be informed [about] and to have access to safe, effective, affordable and acceptable methods of family planning of their choice, as well as other methods for regulation of fertility which are not against the law, and the right of access to appropriate health-care services that will enable women to go safely through pregnancy and childbirth and provide couples with the best chance of having a healthy infant [para. 72].

Unlike previous population conferences, a wide range of interests from grassroots to government level were represented in Cairo. 179 nations attended the ICPD and overall eleven thousand representatives from governments, NGOs, international agencies and citizen activists participated. The ICPD did not address the far-reaching implications of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In 1999, recommendations at the ICPD+5 were expanded to include commitment to AIDS education, research, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission, as well as to the development of vaccines and microbicides.

The Cairo Programme of Action was adopted by 184 UN member states. Nevertheless, many Latin American and Islamic states made formal reservations to the programme, in particular, to its concept of reproductive rights and sexual freedom, to its treatment of abortion, and to its potential incompatibility with Islamic law.

Implementation of the Cairo Programme of Action varies considerably from country to country. In many countries, post-ICPD tensions emerged as the human rights-based approach was implemented. Since the ICPD, many countries have broadened their reproductive health programs and attempted to integrate maternal and child health services with family planning. More attention is paid to adolescent health and the consequences of unsafe abortion. Lara Knudsen observes that the ICPD succeeded in getting feminist language into governments' and population agencies' literature, but in many countries, the underlying concepts are not widely put into practice. In two preparatory meetings for the ICPD+10 in Asia and Latin America, the United States, under the George W. Bush administration, was the only nation opposing the ICPD's Programme of Action.

Beijing Platform

The 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, in its non-binding Declaration and Platform for Action, supported the Cairo Programme's definition of reproductive health, but established a broader context of reproductive rights:

The human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. Equal relationships between women and men in matters of sexual relations and reproduction, including full respect for the integrity of the person, require mutual respect, consent and shared responsibility for sexual behavior and its consequences [para. 96].

The Beijing Platform demarcated twelve interrelated critical areas of the human rights of women that require advocacy. The Platform framed women's reproductive rights as "indivisible, universal and inalienable human rights." The platform for the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women included a section that denounced gender-based violence and included forced sterilization as a human rights violation. However, the international community at large has not confirmed that women have a right to reproductive healthcare and in ensuing years since the 1995 conference, countries have proposed language to weaken reproductive and sexual rights. This conference also referenced for the first time indigenous rights and women's rights at the same time, combining them into one category needing specific representation. Reproductive rights are highly politicized, making it difficult to enact legislation.

Yogyakarta Principles

The Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, proposed by a group of experts in November 2006 but not yet incorporated by States in international law, declares in its Preamble that "the international community has recognized the rights of persons to decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free from coercion, discrimination, and violence." In relation to reproductive health, Principle 9 on "The Right to Treatment with Humanity while in Detention" requires that "States shall... [p]rovide adequate access to medical care and counseling appropriate to the needs of those in custody, recognizing any particular needs of persons on the basis of their sexual orientation and gender identity, including with regard to reproductive health, access to HIV/AIDS information and therapy and access to hormonal or other therapy as well as to gender-reassignment treatments where desired." Nonetheless, African, Caribbean and Islamic Countries, as well as the Russian Federation, have objected to the use of these principles as Human Rights standards.

State interventions

State interventions that contradict at least some reproductive rights have happened both under right-wing and left-wing governments. Examples include attempts to forcefully increase the birth rate – one of the most notorious natalist policies of the 20th century was that which occurred in communist Romania in the period of 1967–1990 during communist leader Nicolae Ceaușescu, who adopted a very aggressive natalist policy which included outlawing abortion and contraception, routine pregnancy tests for women, taxes on childlessness, and legal discrimination against childless people – as well as attempts to decrease the fertility rate – China's one child policy (1978–2015). State mandated forced marriage was also practiced by authoritarian governments as a way to meet population targets: the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia systematically forced people into marriages, in order to increase the population and continue the revolution. Some governments have implemented racist policies of forced sterilizations of 'undesirable' ethnicities. Such policies were carried out against ethnic minorities in Europe and North America in the 20th century, and more recently in Latin America against the Indigenous population in the 1990s; in Peru, President Alberto Fujimori (in office from 1990 to 2000) has been accused of genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of a sterilization program put in place by his administration targeting indigenous people (mainly the Quechuas and the Aymaras).

Prohibition of forced sterilization and forced abortion

The Istanbul convention, the first legally binding instrument in Europe in the field of violence against women and domestic violence, prohibits forced sterilization and forced abortion:

Article 39 – Forced abortion and forced sterilisation

- Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure that the following intentional conducts are criminalised:

- a performing an abortion on a woman without her prior and informed consent;

- b performing surgery which has the purpose or effect of terminating a woman’s capacity to naturally reproduce without her prior and informed consent or understanding of the procedure

Human rights

Human rights have been used as a framework to analyze and gauge abuses, especially for coercive or oppressive governmental policies. The framing of reproductive (human) rights and population control programs are split along race and class lines, with white, western women predominately focused on abortion access (especially during the second wave feminism of the 1970–1980s), silencing women of colour in the Global South or marginalized women in the Global North (black and indigenous women, prisoners, welfare recipients) who were subjected to forced sterilization or contraceptive usage campaigns. The hemisphere divide has also been framed as Global North feminists advocating for women's bodily autonomy and political rights, while Global South women advocate for basic needs through poverty reduction and equality in the economy.

This divide between first world versus third world women established as feminists focused on women's issues (from the first world largely promoting sexual liberation) versus women focused on political issues (from the third world often opposing dictatorships and policies). In Latin America, this is complicated as feminists tend to align with first world ideals of feminism (sexual/reproductive rights, violence against women, domestic violence) and reject religious institutions such as the Catholic Church and Evangelicals, which attempt to control women's reproduction. On the other side, human rights advocates are often aligned with religious institutions that are specifically combating political violence, instead of focusing on issues of individual bodily autonomy.

The debate regarding whether women should have complete autonomous control over their bodies has been espoused by the United Nations and individual countries, but many of those same countries fail to implement these human rights for their female citizens. This shortfall may be partly due to the delay of including women-specific issues in the human rights framework. However, multiple human rights documents and declarations specifically proclaim reproductive rights of women, including the ability to make their own reproductive healthcare decisions regarding family planning, including: the UN Declaration of Human Rights (1948), The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979), the U.N.'s Millennium Development Goals, and the new Sustainable Development Goals, which are focused on integrating universal reproductive healthcare access into national family planning programs. Unfortunately, the 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, did not address indigenous women's reproductive or maternal healthcare rights or access.

Since most existing legally binding international human rights instruments do not explicitly mention sexual and reproductive rights, a broad coalition of NGOs, civil servants, and experts working in international organizations have been promoting a reinterpretation of those instruments to link the realization of the already internationally recognized human rights with the realization of reproductive rights. An example of this linkage is provided by the 1994 Cairo Programme of Action:

Reproductive rights embrace certain human rights that are already recognized in national laws, international human rights documents and other relevant United Nations consensus documents. These rights rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. It also includes the right of all to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence as expressed in human rights documents. In the exercise of this right, they should take into account the needs of their living and future children and their responsibilities towards the community.

Similarly, Amnesty International has argued that the realisation of reproductive rights is linked with the realisation of a series of recognised human rights, including the right to health, the right to freedom from discrimination, the right to privacy, and the right not to be subjected to torture or ill-treatment.

The World Health Organization states that:

Sexual and reproductive health and rights encompass efforts to eliminate preventable maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity, to ensure quality sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptive services, and to address sexually transmitted infections (STI) and cervical cancer, violence against women and girls, and sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents. Universal access to sexual and reproductive health is essential not only to achieve sustainable development but also to ensure that this new framework speaks to the needs and aspirations of people around the world and leads to realisation of their health and human rights.

However, not all states have accepted the inclusion of reproductive rights in the body of internationally recognized human rights. At the Cairo Conference, several states made formal reservations either to the concept of reproductive rights or to its specific content. Ecuador, for instance, stated that:

With regard to the Programme of Action of the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development and in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution and laws of Ecuador and the norms of international law, the delegation of Ecuador reaffirms, inter alia, the following principles embodied in its Constitution: the inviolability of life, the protection of children from the moment of conception, freedom of conscience and religion, the protection of the family as the fundamental unit of society, responsible paternity, the right of parents to bring up their children and the formulation of population and development plans by the Government in accordance with the principles of respect for sovereignty. Accordingly, the delegation of Ecuador enters a reservation with respect to all terms such as "regulation of fertility", "interruption of pregnancy", "reproductive health", "reproductive rights" and "unwanted children", which in one way or another, within the context of the Programme of Action, could involve abortion.

Similar reservations were made by Argentina, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, Malta, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru and the Holy See. Islamic Countries, such as Brunei, Djibouti, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Syria, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen made broad reservations against any element of the programme that could be interpreted as contrary to the Sharia. Guatemala even questioned whether the conference could legally proclaim new human rights.

Women's rights

The reproductive rights of women are advanced in the context of the right to freedom from discrimination and the social and economic status of women. The group Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era (DAWN) explained the link in the following statement:

Control over reproduction is a basic need and a basic right for all women. Linked as it is to women's health and social status, as well as the powerful social structures of religion, state control and administrative inertia, and private profit, it is from the perspective of poor women that this right can best be understood and affirmed. Women know that childbearing is a social, not a purely personal, phenomenon; nor do we deny that world population trends are likely to exert considerable pressure on resources and institutions by the end of this century. But our bodies have become a pawn in the struggles among states, religions, male heads of households, and private corporations. Programs that do not take the interests of women into account are unlikely to succeed...

Women's reproductive rights have long retained key issue status in the debate on overpopulation.

"The only ray of hope I can see – and it's not much – is that wherever women are put in control of their lives, both politically and socially; where medical facilities allow them to deal with birth control and where their husbands allow them to make those decisions, birth rate falls. Women don't want to have 12 kids of whom nine will die." David Attenborough

According to OHCHR: "Women’s sexual and reproductive health is related to multiple human rights, including the right to life, the right to be free from torture, the right to health, the right to privacy, the right to education, and the prohibition of discrimination".

Attempts have been made to analyse the socioeconomic conditions that affect the realisation of a woman's reproductive rights. The term reproductive justice has been used to describe these broader social and economic issues. Proponents of reproductive justice argue that while the right to legalized abortion and contraception applies to everyone, these choices are only meaningful to those with resources and that there is a growing gap between access and affordability.

This more nuanced framework of reproductive justice that recognizes that even with the necessary access to reproductive health, there are other influences beyond choice that determine a women's ability to control her bodily autonomy is discussed in Battles Over Abortion and Reproductive Rights (2017) by Suzanne Staggenborg and Marie B. Skoczylas. They define this concept as detailed below.

Reproductive Justice: interrelationships among issues, linking reproductive health and rights to other social issues (broader human rights framework)

- "White-dominated sectors of the pro-choice movement that focused solely on abortion and downplayed the reality that reproduction is encouraged for some women and discouraged for others" (221)

Men's rights

Recently men's reproductive right with regards to paternity have become subject of debate in the U.S. The term "male abortion" was coined by Melanie McCulley, a South Carolina attorney, in a 1998 article. The theory begins with the premise that when a woman becomes pregnant she has the option of abortion, adoption, or parenthood. A man, however, has none of those options, but will still be affected by the woman's decision. It argues, in the context of legally recognized gender equality, that in the earliest stages of pregnancy the putative (alleged) father should have the right to relinquish all future parental rights and financial responsibility, leaving the informed mother with the same three options. This concept has been supported by a former president of the feminist organization National Organization for Women, attorney Karen DeCrow. The feminist argument for male reproductive choice contends that the uneven ability to choose experienced by men and women in regards to parenthood is evidence of a state-enforced coercion favoring traditional sex roles.

In 2006, the National Center for Men brought a case in the US, Dubay v. Wells (dubbed by some "Roe v. Wade for men"), that argued that in the event of an unplanned pregnancy, when an unmarried woman informs a man that she is pregnant by him, he should have an opportunity to give up all paternity rights and responsibilities. Supporters argue that this would allow the woman time to make an informed decision and give men the same reproductive rights as women. In its dismissal of the case, the U.S. Court of Appeals (Sixth Circuit) stated that "the Fourteenth Amendment does not deny to [the] State the power to treat different classes of persons in different ways."

The opportunity to give men the right for a paper abortion is heavily discussed. Sperm theft is another related issue.

Intersex and reproductive rights

Intersex, in humans and other animals, is a variation in sex characteristics including chromosomes, gonads, or genitals that do not allow an individual to be distinctly identified as male or female. Such variation may involve genital ambiguity, and combinations of chromosomal genotype and sexual phenotype other than XY-male and XX-female. Intersex persons are often subjected to involuntary "sex normalizing" surgical and hormonal treatments in infancy and childhood, often also including sterilization.

UN agencies have begun to take note. On 1 February 2013, Juan E Mendés, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, issued a statement condemning non-consensual surgical intervention on intersex people. His report stated, "Children who are born with atypical sex characteristics are often subject to irreversible sex assignment, involuntary sterilization, involuntary genital normalizing surgery, performed without their informed consent, or that of their parents, "in an attempt to fix their sex", leaving them with permanent, irreversible infertility and causing severe mental suffering". In May 2014, the World Health Organization issued a joint statement on Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization, An interagency statement with the OHCHR, UN Women, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNFPA and UNICEF. The report references the involuntary surgical "sex-normalising or other procedures" on "intersex persons". It questions the medical necessity of such treatments, patients' ability to consent, and a weak evidence base. The report recommends a range of guiding principles to prevent compulsory sterilization in medical treatment, including ensuring patient autonomy in decision-making, ensuring non-discrimination, accountability and access to remedies.

Youth rights and access

Minors

In many jurisdictions minors require parental consent or parental notification in order to access various reproductive services, such as contraception, abortion, gynecological consultations, testing for STIs etc. The requirement that minors have parental consent/notification for testing for HIV/AIDS is especially controversial as it can cause delayed diagnosis and treatment. Balancing minors' rights versus parental rights is considered an ethical problem in medicine and law, and there have been many court cases on this issue in the US. An important concept recognized since 1989 by the Convention on the Rights of the Child is that of the evolving capacities of a minor, namely that minors should, in accordance with their maturity and level of understanding, be involved in decisions that affect them.

Youth are often denied equal access to reproductive health services because health workers view adolescent sexual activity as unacceptable, or see sex education as the responsibility of parents. Providers of reproductive health have little accountability to youth clients, a primary factor in denying youth access to reproductive health care. In many countries, regardless of legislation, minors are denied even the most basic reproductive care, if they are not accompanied by parents: in India, for instance, in 2017, a 17-year-old girl who was rejected by her family due to her pregnancy, was also rejected by hospitals and gave birth in the street. In recent years the lack of reproductive rights for adolescents has been a concern of international organizations, such as UNFPA.

Mandatory involvement of parents in cases where the minor has sufficient maturity to understand their situation is considered by health organization as a violation of minor's rights and detrimental to their health. The World Health Organization has criticized parental consent/notification laws:

Discrimination in health care settings takes many forms and is often manifested when an individual or group is denied access to health care services that are otherwise available to others. It can also occur through denial of services that are only needed by certain groups, such as women. Examples include specific individuals or groups being subjected to physical and verbal abuse or violence; involuntary treatment; breaches of confidentiality and/or denial of autonomous decision-making, such as the requirement of consent to treatment by parents, spouses or guardians; and lack of free and informed consent. ... Laws and policies must respect the principles of autonomy in health care decision-making; guarantee free and informed consent, privacy and confidentiality; prohibit mandatory HIV testing; prohibit screening procedures that are not of benefit to the individual or the public; and ban involuntary treatment and mandatory third-party authorization and notification requirements.

According to UNICEF: "When dealing with sexual and reproductive health, the obligation to inform parents and obtain their consent becomes a significant barrier with consequences for adolescents’ lives and for public health in general." One specific issue which is seen as a form of hypocrisy of legislators is that of having a higher age of medical consent for the purpose of reproductive and sexual health than the age of sexual consent – in such cases the law allows youth to engage in sexual activity, but does not allow them to consent to medical procedures that may arise from being sexually active; UNICEF states that "On sexual and reproductive health matters, the minimum age of medical consent should never be higher than the age of sexual consent."

Africa

Many unintended pregnancies stem from traditional contraceptive methods or no contraceptive measures.

Youth sexual education in Uganda is relatively low. Comprehensive sex education is not generally taught in schools; even if it was, the majority of young people do not stay in school after the age of fifteen, so information would be limited regardless.

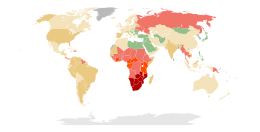

Africa experiences high rates of unintended pregnancy, along with high rates of HIV/AIDS. Young women aged 15–24 are eight times more likely to have HIV/AIDS than young men. Sub-Saharan Africa is the world region most affected by HIV/AIDS, with approximately 25 million people living with HIV in 2015. Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for two-thirds of the global total of new HIV infections.

Attempted abortions and unsafe abortions are a risk for youth in Africa. On average, there are 2.4 million unsafe abortions in East Africa, 1.8 million in Western Africa, over 900,000 in Middle Africa, and over 100,000 in Southern Africa each year. The Guttmacher Institute estimates that, over the time range of 2015 to 2019, 77% of abortions in Sub-Saharan Africa are unsafe, with a fatality rate of 185 deaths per 100,000 abortions, making it the unsafest region for abortions.

In Uganda, abortion is illegal except to save the mother's life. However, 78% of teenagers report knowing someone who has had an abortion and the police do not always prosecute everyone who has an abortion. An estimated 22% of all maternal deaths in the area stem from illegal, unsafe abortions.

As of 2022, the only countries in Africa in which abortion is broadly legal are Benin, Cape Verde, Mozambique, South Africa, and Tunisia. Zambia allows abortion for health or socioeconomic reasons, though there are limitations to access. Discussion about legalizing abortion is ongoing in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, also known as the Maputo Protocol, states in Article 14(2)c that governments must "protect the reproductive rights of women by authorising medical abortion in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest, and where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother or the life of the mother or the foetus." It is the only human rights charter that details conditions for abortion. Since the protocol was written in 2003, 39 countries have ratified it. It has played a significant part in the easing of abortion laws in several African countries.

European Union

Over 85% of European women (all ages) have used some form of birth control in their lives. Europeans as an aggregate report using the pill and condoms as the most commonly used contraceptives.

Sweden has the highest percentage of lifetime contraceptive use, with 96% of its inhabitants claiming to have used birth control at some point in their life. Sweden also has a high self-reported rate of postcoital pill use. A 2007 anonymous survey of Swedish 18-year-olds showed that three out of four youth were sexually active, with 5% reporting having had an abortion and 4% reporting the contraction of an STI.

In the European Union, reproductive rights are protected through the European Convention on Human Rights and its jurisprudence, as well as the Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (the Istanbul Convention). However, these rights are denied or restricted by the laws, policies and practices of member states. In fact, some countries criminalize medical staff, have stricter regulations than the international norm or exclude legal abortion and contraception from public health insurance. A study conducted by Policy Departments, at the request of the European Parliament Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality, recommends the EU to strengthen the legal framework on equal access to sexual and reproductive health goods and services.

Latin America

Latin America has come to international attention due to its harsh anti-abortion laws. Latin America is home to some of the few countries of the world with a complete ban on abortion, without an exception for saving maternal life. In some of these countries, particularity in Central America, the enforcement of such laws is very aggressive: El Salvador and Nicaragua have drawn international attention for strong enforcement of their complete bans on abortion. In 2017, Chile relaxed its total ban, allowing abortion to be performed when the woman's life is in danger, when a fetus is unviable, or in cases of rape.

In Ecuador, education and class play a large role in the definition of which young women become pregnant and which do not – 50% of young women who are illiterate get pregnant, compared to 11% of girls with secondary education. The same is true for poorer individuals – 28% become impregnated while only 11% of young women in wealthier households do. Furthermore, access to reproductive rights, including contraceptives, are limited, due to age and the perception of female morality. Health care providers often discuss contraception theoretically, not as a device to be used on a regular basis. Decisions concerning sexual activity often involve secrecy and taboos, as well as a lack of access to accurate information. Even more telling, young women have much easier access to maternal healthcare than they do to contraceptive help, which helps explain high pregnancy rates in the region.

Rates of adolescent pregnancy in Latin America number over a million each year.

United States

Among sexually experienced teenagers, 78% of teenage females and 85% of teenage males used contraception the first time they had sex; 86% and 93% of these same females and males, respectively, reported using contraception the last time they had sex. The male condom is the most commonly used method during first sex, although 54% of young women in the United States rely upon the pill.

Young people in the U.S. are no more sexually active than individuals in other developed countries, but they are significantly less knowledgeable about contraception and safe sex practices. As of 2006, only twenty states required sex education in schools – of these, only ten required information about contraception. On the whole, less than 10% of American students receive sex education that includes topical coverage of abortion, homosexuality, relationships, pregnancy, and STI prevention. Abstinence-only education was used throughout much of the United States in the 1990s and early 2000s. Based upon the moral principle that sex outside of marriage is unacceptable, the programs often misled students about their rights to have sex, the consequences, and prevention of pregnancy and STIs.

Abortion in the United States was a constitutional right since the United States Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade which decriminalised abortion nationwide in 1973, and established a minimal period during which abortion is legal (with more or fewer restrictions throughout the pregnancy) until this decision was overturned in June 2022 by the decision Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. Abortion rights are now decided at the state level with only California, Michigan, Ohio, and Vermont with explicit rights to abortions. While the state constitutions of Alabama, Louisiana, Tennessee, and West Virginia explicitly contain no right to an abortion.

Lack of knowledge about rights

One of the many reasons why reproductive rights are poor in many places, is not only that they are restricted but that that the vast majority of the population may not know what the law is. Not only are ordinary people uninformed, but so are medical doctors. A study in Brazil on medical doctors found considerable ignorance and misunderstanding of the law on abortion (which is severely restricted, but not completely illegal). In Ghana, abortion, while restricted, is permitted on several grounds, but only 3% of pregnant women and 6% of those seeking an abortion were aware of the legal status of abortion. In Nepal, abortion was legalized in 2002, but a study in 2009 found that only half of women knew that abortion was legalized. Many people also do not understand the laws on sexual violence: in Hungary, where marital rape was made illegal in 1997, in a study in 2006, 62% of people did not know that marital rape was a crime. The United Nations Development Programme states that, in order to advance gender justice, "Women must know their rights and be able to access legal systems", and the 1993 UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women states at Art. 4 (d) [...] "States should also inform women of their rights in seeking redress through such mechanisms". In the UK, Beverley Lawrence Beech understood the importance of women knowing their rights so that they can make decisions about the place and manner of the birth of their children.

Gender equality and violence against women

Addressing issues of gender-based violence is crucial for attaining reproductive rights. The United Nations Population Fund refers to "Equality and equity for men and women, to enable individuals to make free and informed choices in all spheres of life, free from discrimination based on gender" and "Sexual and reproductive security, including freedom from sexual violence and coercion, and the right to privacy," as part of achieving reproductive rights, and states that the right to liberty and security of the person which is fundamental to reproductive rights obliges states to:

- Take measures to prevent, punish and eradicate all forms of gender-based violence

- Eliminate female genital mutilation/cutting

The WHO states:

- Gender and Reproductive Rights (GRR) aims to promote and protect human rights and gender equality as they relate to sexual and reproductive health by developing strategies and mechanisms for promoting gender equity and equality and human rights in the Departments global and national activities, as well as within the functioning and priority-setting of the Department itself.

Amnesty International writes that:

- Violence against women violates women's rights to life, physical and mental integrity, to the highest attainable standard of health, to freedom from torture and it violates their sexual and reproductive rights.

One key issue for achieving reproductive rights is criminalization of sexual violence. If a woman is not protected from forced sexual intercourse, she is not protected from forced pregnancy, namely pregnancy from rape. In order for a woman to be able to have reproductive rights, she must have the right to choose with whom and when to reproduce; and first of all, decide whether, when, and under what circumstances to be sexually active. In many countries, these rights of women are not respected, because women do not have a choice in regard to their partner, with forced marriage and child marriage being common in parts of the world; and neither do they have any rights in regard to sexual activity, as many countries do not allow women to refuse to engage in sexual intercourse when they do not want to (because marital rape is not criminalized in those countries) or to engage in consensual sexual intercourse if they want to (because sex outside marriage is illegal in those countries). In addition to legal barriers, there are also social barriers, because in many countries a complete sexual subordination of a woman to her husband is expected (for instance, in one survey 74% of women in Mali said that a husband is justified to beat his wife if she refuses to have sex with him), while sexual/romantic relations disapproved by family members, or generally sex outside marriage, can result in serious violence, such as honor killings.

HIV/AIDS

| No data <0.10 0.10–0.5 0.5–1 | 1–5 5–15 15–50 |

According to the CDC, "HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus. It weakens a person’s immune system by destroying important cells that fight disease and infection. No effective cure exists for HIV. But with proper medical care, HIV can be controlled." HIV amelioration is an important aspect of reproductive rights because the virus can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy or birth, or via breast milk.

The WHO states that: "All women, including those with HIV, have the right "to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights"". The reproductive rights of people living with HIV, and their health, are very important. The link between HIV and reproductive rights exists in regard to four main issues:

- prevention of unwanted pregnancy

- help to plan wanted pregnancy

- healthcare during and after pregnancy

- access to abortion services

Child and forced marriage

The WHO states that the reproductive rights and health of girls in child marriages are negatively affected. The UNPF calls child marriage a "human rights violation" and states that in developing countries, one in every three girls is married before reaching age 18, and one in nine is married under age 15. A forced marriage is a marriage in which one or more of the parties is married without his or her consent or against his or her will. The Istanbul convention, the first legally binding instrument in Europe in the field of violence against women and domestic violence, requires countries which ratify it to prohibit forced marriage (Article 37) and to ensure that forced marriages can be easily voided without further victimization (Article 32).

Sexual violence in armed conflict

Sexual violence in armed conflict is sexual violence committed by combatants during armed conflict, war, or military occupation often as spoils of war; but sometimes, particularly in ethnic conflict, the phenomenon has broader sociological motives. It often includes gang rape. Rape is often used as a tactic of war and a threat to international security. Sexual violence in armed conflict is a violation of reproductive rights, and often leads to forced pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. Such sexual violations affect mostly women and girls, but rape of men can also occur, such as in Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Maternal mortality

Maternal death is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes." It is estimated that in 2015, about 303,000 women died during and following pregnancy and childbirth, and 99% of such deaths occur in developing countries.

Issues

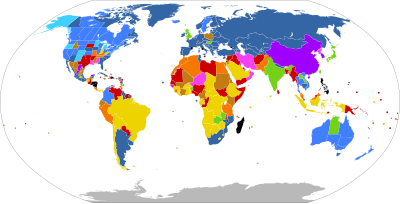

Birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception and fertility control, is a method or device used to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only became available in the 20th century. Planning, making available, and using birth control is called family planning. Some cultures limit or discourage access to birth control because they consider it to be morally, religiously, or politically undesirable.

All birth control methods meet opposition, especially religious opposition, in some parts of the world. Opposition does not only target modern methods, but also 'traditional' ones; for example, the Quiverfull movement, a conservative Christian ideology, encourages the maximization of procreation, and opposes all forms of birth control, including natural family planning.

Abortion

According to a study by WHO and the Guttmacher Institute worldwide, 25 million unsafe abortions (45% of all abortions) occurred every year between 2010 and 2014. 97% of unsafe abortions occur in developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. By contrast, most abortions that take place in Western and Northern Europe and North America are safe.

The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women considers the criminalization of abortion a "violations of women's sexual and reproductive health and rights" and a form of "gender-based violence"; paragraph 18 of its General recommendation No. 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating general recommendation No. 19 states that: "Violations of women's sexual and reproductive health and rights, such as forced sterilizations, forced abortion, forced pregnancy, criminalisation of abortion, denial or delay of safe abortion and post-abortion care, forced continuation of pregnancy, abuse and mistreatment of women and girls seeking sexual and reproductive health information, goods and services, are forms of gender based violence that, depending on the circumstances, may amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment." The same General Recommendation also urges countries at paragraph 31 to [...] "In particular, repeal: a) Provisions that allow, tolerate or condone forms of gender-based violence against women, including [...] legislation that criminalises abortion."

An article from the World Health Organization calls safe, legal abortion a "fundamental right of women, irrespective of where they live" and unsafe abortion a "silent pandemic". The article states "ending the silent pandemic of unsafe abortion is an urgent public-health and human-rights imperative." It also states "access to safe abortion improves women's health, and vice versa, as documented in Romania during the regime of President Nicolae Ceaușescu" and "legalisation of abortion on request is a necessary but insufficient step toward improving women's health" citing that in some countries, such as India where abortion has been legal for decades, access to competent care remains restricted because of other barriers. WHO's Global Strategy on Reproductive Health, adopted by the World Health Assembly in May 2004, noted: "As a preventable cause of maternal mortality and morbidity, unsafe abortion must be dealt with as part of the MDG on improving maternal health and other international development goals and targets." The WHO's Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), whose research concerns people's sexual and reproductive health and lives, has an overall strategy to combat unsafe abortion that comprises four inter-related activities:

- to collate, synthesize and generate scientifically sound evidence on unsafe abortion prevalence and practices;

- to develop improved technologies and implement interventions to make abortion safer;

- to translate evidence into norms, tools and guidelines;

- and to assist in the development of programmes and policies that reduce unsafe abortion and improve access to safe abortion and high quality post-abortion care

The UN has estimated in 2017 that repealing anti-abortion laws would save the lives of nearly 50,000 women a year. 209,519 abortions take place in England and Wales alone. Unsafe abortions take place primarily in countries where abortion is illegal, but also occur in countries where it is legal. Despite its legal status, an abortion is de facto hardly optional for women due to most doctors being conscientious objectors. Other reasons include the lack of knowledge that abortions are legal, lower socioeconomic backgrounds and spatial disparities. Concerns have been raised about these practical considerations; the UN in its 2017 resolution on Intensification of efforts to prevent and eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls: domestic violence urged states to guarantee access to "safe abortion where such services are permitted by national law". In 2008, Human Rights Watch stated that "In fact, even where abortion is permitted by law, women often have severely limited access to safe abortion services because of lack of proper regulation, health services, or political will" and estimated that "Approximately 13 percent of maternal deaths worldwide are attributable to unsafe abortion—between 68,000 and 78,000 deaths annually."

The Maputo Protocol, which was adopted by the African Union in the form of a protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, states at Article 14 (Health and Reproductive Rights) that: "(2). States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to: [...] c) protect the reproductive rights of women by authorising medical abortion in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest, and where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother or the life of the mother or the foetus." The Maputo Protocol is the first international treaty to recognize abortion, under certain conditions, as a woman's human right.

The General comment No. 36 (2018) on article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, on the right to life, adopted by the Human Rights Committee in 2018, defines, for the first time ever, a human right to abortion – in certain circumstances (however these UN general comments are considered soft law, and, as such, not legally binding).

Although States parties may adopt measures designed to regulate voluntary terminations of pregnancy, such measures must not result in violation of the right to life of a pregnant woman or girl, or her other rights under the Covenant. Thus, restrictions on the ability of women or girls to seek abortion must not, inter alia, jeopardize their lives, subject them to physical or mental pain or suffering which violates article 7, discriminate against them or arbitrarily interfere with their privacy. States parties must provide safe, legal and effective access to abortion where the life and health of the pregnant woman or girl is at risk, and where carrying a pregnancy to term would cause the pregnant woman or girl substantial pain or suffering, most notably where the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest or is not viable. In addition, States parties may not regulate pregnancy or abortion in all other cases in a manner that runs contrary to their duty to ensure that women and girls do not have to undertake unsafe abortions, and they should revise their abortion laws accordingly. For example, they should not take measures such as criminalizing pregnancies by unmarried women or apply criminal sanctions against women and girls undergoing abortion or against medical service providers assisting them in doing so, since taking such measures compel women and girls to resort to unsafe abortion. States parties should not introduce new barriers and should remove existing barriers that deny effective access by women and girls to safe and legal abortion, including barriers caused as a result of the exercise of conscientious objection by individual medical providers.

When negotiating the Cairo Programme of Action at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), the issue was so contentious that delegates eventually decided to omit any recommendation to legalize abortion, instead advising governments to provide proper post-abortion care and to invest in programs that will decrease the number of unwanted pregnancies.

On 18 April 2008 the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, a group comprising members from 47 European countries, adopted a resolution calling for the decriminalization of abortion within reasonable gestational limits and guaranteed access to safe abortion procedures. The nonbinding resolution was passed on 16 April by a vote of 102 to 69.

During and after the ICPD, some interested parties attempted to interpret the term "reproductive health" in the sense that it implies abortion as a means of family planning or, indeed, a right to abortion. These interpretations, however, do not reflect the consensus reached at the Conference. For the European Union, where legislation on abortion is certainly less restrictive than elsewhere, the Council Presidency has clearly stated that the Council's commitment to promote "reproductive health" did not include the promotion of abortion. Likewise, the European Commission, in response to a question from a Member of the European Parliament, clarified:

The term reproductive health was defined by the United Nations (UN) in 1994 at the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development. All Member States of the Union endorsed the Programme of Action adopted at Cairo. The Union has never adopted an alternative definition of 'reproductive health' to that given in the Programme of Action, which makes no reference to abortion.

With regard to the U.S., only a few days prior to the Cairo Conference, the head of the U.S. delegation, Vice President Al Gore, had stated for the record:

Let us get a false issue off the table: the US does not seek to establish a new international right to abortion, and we do not believe that abortion should be encouraged as a method of family planning.

Some years later, the position of the U.S. administration in this debate was reconfirmed by U.S. Ambassador to the UN, Ellen Sauerbrey, when she stated at a meeting of the UN Commission on the Status of Women that: "nongovernmental organizations are attempting to assert that Beijing in some way creates or contributes to the creation of an internationally recognized fundamental right to abortion". She added: "There is no fundamental right to abortion. And yet it keeps coming up largely driven by NGOs trying to hijack the term and trying to make it into a definition".

Collaborative research from the Institute of Development Studies states that "access to safe abortion is a matter of human rights, democracy and public health, and the denial of such access is a major cause of death and impairment, with significant costs to [international] development". The research highlights the inequities of access to safe abortion both globally and nationally and emphasises the importance of global and national movements for reform to address this. The shift by campaigners of reproductive rights from an issue-based agenda (the right to abortion), to safe, legal abortion not only as a human right, but bound up with democratic and citizenship rights, has been an important way of reframing the abortion debate and reproductive justice agenda.

Meanwhile, the European Court of Human Rights complicated the question even more through a landmark judgment (case of A. B. and C. v. Ireland), in which it is stated that the denial of abortion for health and/or well-being reasons is an interference with an individual's right to respect for private and family life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, an interference which in some cases can be justified.

Population control

A desire to achieve certain population targets has resulted throughout history in severely abusive practices, in cases where governments ignored human rights and enacted aggressive demographic policies. In the 20th century, several authoritarian governments have sought either to increase or to decrease the births rates, often through forceful intervention. One of the most notorious natalist policies is that which occurred in communist Romania in the period of 1967–1990 during communist leader Nicolae Ceaușescu, who adopted a very aggressive natalist policy which included outlawing abortion and contraception, routine pregnancy tests for women, taxes on childlessness, and legal discrimination against childless people. Ceaușescu's policy resulted in over 9,000 women who died due to illegal abortions, large numbers of children put into Romanian orphanages by parents who could not cope with raising them, street children in the 1990s (when many orphanages were closed and the children ended on the streets), and overcrowding in homes and schools. The irony of Ceaușescu's aggressive natalist policy was a generation that may not have been born would eventually lead the Romanian Revolution which would overthrow and have him executed.

In stark opposition with Ceaușescu's natalist policy was China's one-child policy, in effect from 1978 to 2015, which included abuses such as forced abortions. This policy has also been deemed responsible for the common practice of sex-selective abortion which led to an imbalanced sex ratio in the country.

From the 1970s to 1980s, tension grew between women's health activists who advance women's reproductive rights as part of a human rights-based approach on the one hand, and population control advocates on the other. At the 1984 UN World Population Conference in Mexico City population control policies came under attack from women's health advocates who argued that the policies' narrow focus led to coercion and decreased quality of care, and that these policies ignored the varied social and cultural contexts in which family planning was provided in developing countries. In the 1980s the HIV/AIDS epidemic forced a broader discussion of sex into the public discourse in many countries, leading to more emphasis on reproductive health issues beyond reducing fertility. The growing opposition to the narrow population control focus led to a significant departure in the early 1990s from past population control policies. In the United States, abortion opponents have begun to foment conspiracy theories about reproductive rights advocates, accusing them of advancing a racist agenda of eugenics, and of trying to reduce the African American birth rate in the U.S.

Female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons." The procedure has no health benefits, and can cause severe bleeding and problems urinating, cysts, infections, and complications in childbirth and increased risk of newborn deaths. It is performed for traditional, cultural or religious reasons in many parts of the world, especially in Africa, and in some parts of Asia, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Iraqi Kurdistan, and Yemen. The Istanbul Convention prohibits FGM (Article 38). It is estimated that 200 million women worldwide had undergone FGM, including at least 500,000 immigrant women in Europe. Infibulation, also referred to as Type 3 FGM, is the most extreme form of FGM, and is practiced mainly in northeastern Africa, particularly in Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan.

Bride kidnapping or buying and reproductive slavery

Bride kidnapping or marriage by abduction, is the practice whereby a woman or girl is abducted for the purpose of a forced marriage. Bride kidnapping has been practiced historically in many parts of the world, and it continues to occur today in some places, especially in Central Asia and the Caucasus, in countries such as Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Armenia, as well as in Ethiopia. Bride kidnapping is often preceded or followed by rape (which may result in pregnancy), in order to force the marriage – a practice also supported by "marry-your-rapist law" (laws regarding sexual violence, abduction or similar acts, whereby the perpetrator avoids prosecution or punishment if he marries the victim). Abducting of women may happen on an individual scale or on a mass scale. Raptio is a Latin term referring to the large-scale abduction of women, usually for marriage or sexual slavery, particularly during wartime.

Bride price, also called bridewealth, is money, property, or other form of wealth paid by a groom or his family to the parents of the woman he marries. The practice of bride price sometimes leads to parents selling young daughters into marriage and to trafficking. Bride price is common across Africa. Such forced marriages often lead to sexual violence, and forced pregnancy. In northern Ghana, for example, the payment of bride price signifies a woman's requirement to bear children, and women using birth control are at risks of threats and coercion.

The 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery defines "institutions and practices similar to slavery" to include:

c) Any institution or practice whereby:

- (i) A woman, without the right to refuse, is promised or given in marriage on payment of a consideration in money or in kind to her parents, guardian, family or any other person or group; or

- (ii) The husband of a woman, his family, or his clan, has the right to transfer her to another person for value received or otherwise; or

- (iii) A woman on the death of her husband is liable to be inherited by another person;

Sperm donation

Laws in many countries and states require sperm donors to be either anonymous or known to the recipient, or the laws restrict the number of children each donor may father. Although many donors choose to remain anonymous, new technologies such as the Internet and DNA technology have opened up new avenues for those wishing to know more about the biological father, siblings and half-siblings.

Compulsory sterilization

Ethnic minority women

Ethnic minority women have often been victims of forced sterilization programs, such as Amerindian women in parts of Latin America of Roma women.

In Peru, President Alberto Fujimori (in office from 1990 to 2000) has been accused of genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of the Programa Nacional de Población, a sterilization program put in place by his administration. During his presidency, Fujimori put in place a program of forced sterilizations against indigenous people (mainly the Quechuas and the Aymaras), in the name of a "public health plan", presented on 28 July 1995.

During the 20th century, forced sterilization of Roma women in European countries, especially in former Communist countries, was practiced, and there are allegations that these practices continue unofficially in some countries, such as Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania. In V. C. vs. Slovakia, the European Court for Human Rights ruled in favor of a Roma woman who was the victim of forced sterilization in a state hospital in Slovakia in 2000.

United States

Forced sterilization in the United States was practiced starting with the 19th century. The United States during the Progressive era, ca. 1890 to 1920, was the first country to concertedly undertake compulsory sterilization programs for the purpose of eugenics. Thomas C. Leonard, professor at Princeton University, describes American eugenics and sterilization as ultimately rooted in economic arguments and further as a central element of Progressivism alongside wage controls, restricted immigration, and the introduction of pension programs. The heads of the programs were avid proponents of eugenics and frequently argued for their programs, which achieved some success nationwide, mainly in the first half of the 20th century.

Canada

Compulsory sterilization has been practiced historically in parts of Canada. Two Canadian provinces (Alberta and British Columbia) performed compulsory sterilization programs in the 20th century with eugenic aims. Canadian compulsory sterilization operated via the same overall mechanisms of institutionalization, judgment, and surgery as the American system. However, one notable difference is in the treatment of non-insane criminals. Canadian legislation never allowed for punitive sterilization of inmates.

The Sexual Sterilization Act of Alberta was enacted in 1928 and repealed in 1972. In 1995, Leilani Muir sued the Province of Alberta for forcing her to be sterilized against her will and without her permission in 1959. Since Muir's case, the Alberta government has apologized for the forced sterilization of over 2,800 people. Nearly 850 Albertans who were sterilized under the Sexual Sterilization Act were awarded CA$142 million in damages.

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church is opposed to artificial contraception, abortion, and sexual intercourse outside marriage. This belief dates back to the first centuries of Christianity. While Roman Catholicism is not the only religion with such views, its religious doctrine is very powerful in influencing countries where most of the population is Catholic, and the few countries of the world with complete bans on abortion are mostly Catholic-majority countries, and in Europe strict restrictions on abortion exist in the Catholic majority countries of Malta (complete ban), Andorra, San Marino, Liechtenstein and to a lesser extent Poland and Monaco.

In France, a country with a Roman Catholic tradition, abortionist Marie-Louise Giraud was guillotined on 30 July 1943 under the authoritarian Vichy regime.

Some of the countries of Central America, notably El Salvador, have also come to international attention due to very forceful enforcement of the anti-abortion laws. El Salvador has received repeated criticism from the UN. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) named the law "one of the most draconian abortion laws in the world", and urged liberalization, and Zeid bin Ra'ad, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, stated that he was "appalled that as a result of El Salvador’s absolute prohibition on abortion, women are being punished for apparent miscarriages and other obstetric emergencies, accused and convicted of having induced termination of pregnancy".

Anti-abortion violence

Criticism surrounds certain forms of anti-abortion activism. Anti-abortion violence is a serious issue in some parts of the world, especially in North America. It is recognized as single-issue terrorism. Numerous organizations have also recognized anti-abortion extremism as a form of Christian terrorism.

Incidents include vandalism, arson, and bombings of abortion clinics, such as those committed by Eric Rudolph (1996–98), and murders or attempted murders of physicians and clinic staff, as committed by James Kopp (1998), Paul Jennings Hill (1994), Scott Roeder (2009), Michael F. Griffin (1993), and Peter James Knight (2001). Since 1978, in the US, anti-abortion violence includes at least 11 murders of medical staff, 26 attempted murders, 42 bombings, and 187 arsons.