Palestinian nationalism is the national movement of the Palestinian people that espouses self-determination and sovereignty over the region of Palestine. Originally formed in the early 20th century in opposition to Zionism, Palestinian nationalism later internationalized and attached itself to other ideologies; it has thus rejected the occupation of the Palestinian territories by the government of Israel since the 1967 Six-Day War. Palestinian nationalists often draw upon broader political traditions in their ideology, examples being Arab socialism and ethnic nationalism in the context of Muslim religious nationalism. Related beliefs have shaped the government of Palestine and continue to do so.

In the broader context of the Arab–Israeli conflict in the 21st century, Palestinan nationalist aims have included an end to the refugee status of individuals separated from their native lands during the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight, advocates stating that a "right of return" exists either to the occupied territories or to both those areas plus places within Israel itself. Nationalists have additionally worked to advance specific causes in terms of current residents' lives such as freedom of assembly, labor rights, the right to health care, and the right to travel. Divisions between nationalists frequently stir up tense standoffs over particular ideological goals, an example being the gulf between Islamist Palestinians favoring a more authoritarian state compared to centrist and secular peoples supporting democratic self-determination. Palestinians favoring nonviolent resistance also frequently clash with ultra-nationalists who advocate for and engage in political violence both inside and outside Israel.

Origins and starting points

Zachary J. Foster argued in a 2015 Foreign Affairs article that "based on hundreds of manuscripts, Islamic court records, books, magazines, and newspapers from the Ottoman period (1516–1918), it seems that the first Arab to use the term "Palestinian" was Farid Georges Kassab, a Beirut-based Orthodox Christian." He explained further that Kassab’s 1909 book Palestine, Hellenism, and Clericalism noted in passing that "the Orthodox Palestinian Ottomans call themselves Arabs, and are in fact Arabs", despite describing the Arabic speakers of Palestine as Palestinians throughout the rest of the book." The Palestinian Arab Christian Falastin newspaper had addressed its readers as Palestinians since its inception in 1911 during the Ottoman period.

Foster later revised his view in a 2016 piece published in Palestine Square, arguing that already in 1898 Khalil Beidas used the term "Palestinian" to describe the region's Arab inhabitants in the preface to a book he translated from Russian to Arabic. In the book, Akim Olesnitsky's A Description of the Holy Land, Beidas explained that the summer agricultural work in Palestine began in May with the wheat and barley harvest. After enduring the entire summer with no rain at all—leaving the water cisterns depleted and the rivers and springs dry—"the Palestinian peasant waits impatiently for winter to come, for the season's rain to moisten his fossilized fields." Foster explained that this is the first instance in modern history where the term 'Palestinian' or 'Filastini' appears in Arabic. He added, though, that the term Palestinian had already been used decades earlier in Western languages by the 1846–1863 British Consul in Jerusalem, James Finn; the German Lutheran missionary Johann Ludwig Schneller (1820–1896), founder of the Syrian Orphanage; and the American James Wells.

In his 1997 book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, historian Rashid Khalidi notes that the archaeological strata that denote the history of Palestine—encompassing the Biblical, Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Fatimid, Crusader, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman periods—form part of the identity of the modern-day Palestinian people, as they have come to understand it over the last century, but derides the efforts of some Palestinian nationalists to attempt to "anachronistically" read back into history a nationalist consciousness that is in fact "relatively modern." Khalidi stresses that Palestinian identity has never been an exclusive one, with "Arabism, religion, and local loyalties" playing an important role. He argues that the modern national identity of Palestinians has its roots in nationalist discourses that emerged among the peoples of the Ottoman Empire in the late 19th century which sharpened following the demarcation of modern nation-state boundaries in the Middle East after World War I. He acknowledges that Zionism played a role in shaping this identity, though "it is a serious mistake to suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to Zionism." Khalidi describes the Arab population of British Mandatory Palestine as having "overlapping identities", with some or many expressing loyalties to villages, regions, a projected nation of Palestine, an alternative of inclusion in a Greater Syria, an Arab national project, as well as to Islam. He writes that, "local patriotism could not yet be described as nation-state nationalism."

Israeli historian Haim Gerber, a professor of Islamic History at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, traces Arab nationalism back to a 17th-century religious leader, Mufti Khayr al-Din al-Ramli (1585–1671) who lived in Ramla. He claims that Khayr al-Din al-Ramli's religious edicts (fatwa, plural fatawa), collected into final form in 1670 under the name al-Fatawa al-Khayriyah, attest to territorial awareness: "These fatawa are a contemporary record of the time, and also give a complex view of agrarian relations." The 1670 collection mentions the concepts Filastin, biladuna (our country), al-Sham (Syria), Misr (Egypt), and diyar (country), in senses that appear to go beyond objective geography. Gerber describes this as "embryonic territorial awareness, though the reference is to social awareness rather than to a political one."

Baruch Kimmerling and Joel Migdal consider the 1834 Arab revolt in Palestine as the first formative event of the Palestinian people, whereas Benny Morris attests that the Arabs in Palestine remained part of a larger Pan-Islamist or Pan-Arab national movement.

In his book The Israel–Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War, James L. Gelvin states that "Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement." However, this does not make Palestinian identity any less legitimate: "The fact that Palestinian nationalism developed later than Zionism and indeed in response to it does not in any way diminish the legitimacy of Palestinian nationalism or make it less valid than Zionism. All nationalisms arise in opposition to some "other." Why else would there be the need to specify who you are? And all nationalisms are defined by what they oppose."

Bernard Lewis argues it was not as a Palestinian nation that the Palestinian Arabs of the Ottoman Empire objected to Zionists, since the very concept of such a nation was unknown to the Arabs of the area at the time and did not come into being until later. Even the concept of Arab nationalism in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire "had not reached significant proportions before the outbreak of World War I."

Daniel Pipes asserts that "No 'Palestinian Arab people' existed at the start of 1920 but by December it took shape in a form recognizably similar to today's." Pipes argues that with the carving of the British Mandate of Palestine out of Greater Syria, the Arabs of the new Mandate were forced to make the best they could of their situation, and therefore began to define themselves as Palestinian.

Late Ottoman context

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire was accompanied by an increasing sense of Arab identity in the Empire's Arab provinces, most notably Syria, considered to include both northern Palestine and Lebanon. This development is often seen as connected to the wider reformist trend known as al-Nahda ("awakening", sometimes called "the Arab renaissance"), which in the late 19th century brought about a redefinition of Arab cultural and political identities with the unifying feature of Arabic.

Under the Ottomans, Palestine's Arab population mostly saw themselves as Ottoman subjects. In the 1830s however, Palestine was occupied by the Egyptian vassal of the Ottomans, Muhammad Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha. The Palestinian Arab revolt was precipitated by popular resistance against heavy demands for conscripts, as peasants were well aware that conscription was little more than a death sentence. Starting in May 1834 the rebels took many cities, among them Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus. In response, Ibrahim Pasha sent in an army, finally defeating the last rebels on 4 August in Hebron.

While Arab nationalism, at least in an early form, and Syrian nationalism were the dominant tendencies along with continuing loyalty to the Ottoman state, Palestinian politics were marked by a reaction to foreign predominance and the growth of foreign immigration, particularly Zionist.

The Egyptian occupation of Palestine in the 1830s resulted in the destruction of Acre and thus, the political importance of Nablus increased. The Ottomans wrested back control of Palestine from the Egyptians in 1840-41. As a result, the Abd al-Hadi clan, who originated in Arrabah in the Sahl Arraba region in northern Samaria, rose to prominence. Loyal allies of Jezzar Pasha and the Tuqans, they gained the governorship of Jabal Nablus and other sanjaqs.

In 1887 the Mutassariflik (Mutasarrifate) of Jerusalem was constituted as part of an Ottoman government policy dividing the vilayet of Greater Syria into smaller administrative units. The administration of the mutasarrifate took on a distinctly local appearance.

Michelle Compos records that "Later, after the founding of Tel Aviv in 1909, conflicts over land grew in the direction of explicit national rivalry." Zionist ambitions were increasingly identified as a threat by Palestinian leaders, while cases of purchase of lands by Zionist settlers and the subsequent eviction of Palestinian peasants aggravated the issue.

The programmes of four Palestinian nationalist societies jamyyat al-Ikha’ wal-‘Afaf (Brotherhood and Purity), al-jam’iyya al-Khayriyya al-Islamiyya (Islamic Charitable Society), Shirkat al-Iqtissad al-Falastini al-Arabi (lit. Arab Palestinian Economic Association) and Shirkat al-Tijara al-Wataniyya al-Iqtisadiyya (lit. National Economic Trade Association) were reported in the newspaper Filastin in June 1914 by letter from R. Abu al-Sal’ud. The four societies has similarities in function and ideals; the promotion of patriotism, educational aspirations and support for national industries.

British Mandate period

Nationalist groups built around notables

Palestinian Arab A’ayan ("Notables") were a group of urban elites at the apex of the Palestinian socio-economic pyramid where the combination of economic and political power dominated Palestinian Arab politics throughout the British Mandate period. The dominance of the A’ayan had been encouraged and utilised during the Ottoman period and later, by the British during the Mandate period, to act as intermediaries between the authority and the people to administer the local affairs of Palestine.

Al-Husseini

The al-Husayni family were a major force in rebelling against Muhammad Ali who governed Egypt and Palestine in defiance of the Ottoman Empire. This solidified a cooperative relationship with the returning Ottoman authority. The family took part in fighting the Qaisi family in an alliance with a rural lord of the Jerusalem area Mustafa Abu Ghosh, who clashed with the tribe frequently. The feuds gradually occurred in the city between the clan and the Khalidis that led the Qaisis however these conflicts dealt with city positions and not Qaisi-Yamani rivalry.

The Husaynis later led resistance and propaganda movements against the Young Turks who controlled the Ottoman Empire and more so against the British Mandate government and early Zionist immigration. Jamal al-Husayni was the founder and chairman of the Palestine Arab Party (PAP) in 1935. Emil Ghoury was elected as General Secretary, a post he held until the end of the British Mandate in 1948. In 1948, after Jordan had occupied Jerusalem, King Abdullah of Jordan removed Hajj Amīn al-Husayni from the post of Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and banned him from entering Jerusalem.

Nashashibi

The Nashashibi family had particularly strong influence in Palestine during the British Mandate Period from 1920 until 1948. Throughout this period, they competed with the Husaynis, for dominance of the Palestinian Arab political scene. As with other A’ayan their lack of identification with the Palestinian Arab population allowed them to rise as leaders but not as representatives of the Palestinian Arab community. The Nashashibi family was led by Raghib Nashashibi, who was appointed as Mayor of Jerusalem in 1920. Raghib was an influential political figure throughout the British Mandate period, and helped form the National Defence Party in 1934. He also served as a minister in the Jordanian government, governor of the West Bank, member of the Jordanian Senate, and the first military governor in Palestine.

Tuqan

The Tuqan family, originally from northern Syria, was led by Hajj Salih Pasha Tuqan in the early eighteenth century and were the competitors of the Nimr family in the Jabal Nablus (the sub-district of Nablus and Jenin). Members of the Tuqan family held the post of mutasallim (sub-district governor) longer than did any other family in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.The rivalry between the Tuqans and Nimr family continued until the 1820s.

Abd al-Hadi

Awni Abd al-Hadi of the ‘Abd al Hadi family. The Abd al-Hadis were a leading landowning family in the Palestinian districts of Afula, Baysan, Jenin, and Nablus. Awni established the Hizb al-Istiqlal (Independence Party) as a branch of the pan-Arab party. Rushdi Abd al-Hadi joined the British administrative service in 1921. Amin Abd al-Hadi joined the SMC in 1929, and Tahsin Abd al-Hadi was mayor of Jenin. Some family members secretly sold their shares of Zirʿin village to the Jewish National Fund in July 1930 despite nationalist opposition to such land sales. Tarab ‘Abd al Hadi feminist and activist was the wife of Awni ‘Abd al Hadi, Abd al-Hadi Palace built by Mahmud ‘Abd al Hadi in Nablus stands testament to the power and prestige of the family.

Khalidiy, al-Dajjani, al-Shanti

Other A’ayan were the Khalidi family, al-Dajjani family, and the al-Shanti family. The views of the A’ayan and their allies largely shaped the divergent political stances of Palestinian Arabs at the time. In 1918, as the Palestinian Arab national movements gained strength in Jerusalem, Jaffa, Haifa, Acre and Nablus, Aref al-Aref joined Hajj Amīn, his brother Fakhri Al Husseini, Ishaaq Darweesh, Ibrahim Darweesh, Jamal al-Husayni, Kamel Al Budeiri, and Sheikh Hassan Abu Al-So’oud in establishing the Arab Club.

1918–1920 nationalist activity

Following the arrival of the British a number of Muslim-Christian Associations were established in all the major towns. In 1919 they joined together to hold the first Palestine Arab Congress in Jerusalem. Its main platforms were a call for representative government and opposition to the Balfour Declaration.

The Faisal-Weizmann Agreement led the Palestinian Arab population to reject the Syrian-Arab-Nationalist movement led by Faisal (in which many previously placed their hopes) and instead to agitate for Palestine to become a separate state, with an Arab majority. To further that objective, they demanded an elected assembly. In 1919, in response to Palestinian Arab fears of the inclusion of the Balfour declaration to process the secret society al-Kaff al-Sawada’ (the Black-hand, its name soon changed to al-Fida’iyya, The Self-Sacrificers) was founded, it later played an important role in clandestine anti-British and anti-Zionist activities. The society was run by the al-Dajjani and al-Shanti families, with Ibrahim Hammani in charge of training and ‘Isa al-Sifri developed a secret code for correspondence. The society was initially based in Jaffa but moved its headquarters to Nablus, the Jerusalem branch was run by Mahmud Aziz al-Khalidi.

After the April riots an event took place that turned the traditional rivalry between the Husayni and Nashashibi clans into a serious rift, with long-term consequences for al-Husayni and Palestinian nationalism. According to Sir Louis Bols, great pressure was brought to bear on the military administration from Zionist leaders and officials such as David Yellin, to have the Mayor of Jerusalem, Mousa Kazzim al-Husayni, dismissed, given his presence in the Nabi Musa riots of the previous March. Colonel Storrs, the Military Governor of Jerusalem, removed him without further inquiry, replacing him with Raghib. This, according to the Palin report, 'had a profound effect on his co-religionists, definitely confirming the conviction they had already formed from other evidence that the Civil Administration was the mere puppet of the Zionist Organization.'

Supreme Muslim Council under Hajj Amin (1921–1937)

The High Commissioner of Palestine, Herbert Samuel, as a counterbalance the Nashashibis gaining the position of Mayor of Jerusalem, pardoned Hajj Amīn and Aref al-Aref and established a Supreme Muslim Council (SMC), or Supreme Muslim Sharia Council, on 20 December 1921. The SMC was to have authority over all the Muslim Waqfs (religious endowments) and Sharia (religious law) Courts in Palestine. The members of the Council were to be elected by an electoral college and appointed Hajj Amīn as president of the Council with the powers of employment over all Muslim officials throughout Palestine. The Anglo American committee termed it a powerful political machine.

The Hajj Amin rarely delegated authority, consequently most of the council's executive work was carried out by Hajj Amīn. Nepotism and favoritism played a central part to Hajj Amīn's tenure as president of the SMC, Amīn al-Tamīmī was appointed as acting president when the Hajj Amīn was abroad, The secretaries appointed were ‘Abdallah Shafĩq and Muhammad al’Afĩfĩ and from 1928 to 1930 the secretary was Hajj Amīn's relative Jamāl al-Husaynī, Sa’d al Dīn al-Khaţīb and later another of the Hajj Amīn's relatives ‘Alī al-Husaynī and ‘Ajaj Nuwayhid, a Druze was an adviser.

Politicisation of the Wailing Wall

It was during the British mandate period that politicisation of the Wailing Wall occurred. The disturbances at the Wailing wall in 1928 were repeated in 1929, however the violence in the riots that followed, that left 116 Palestinian Arabs, 133 Jews dead and 339 wounded, were surprising in their intensity.

Black Hand gang

Izz ad-Din al-Qassam established the Black Hand gang in 1935. Izz ad-Din died in a shootout against the British forces. He has been popularised in Palestinian nationalist folklore for his fight against Zionism.

1936–1939 Arab revolt

The Great revolt 1936–1939 was an uprising by Palestinian Arabs in the British Mandate of Palestine in protest against mass Jewish immigration.

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni, a leader of the revolt, was a member of the Palestine Arab Party who had served as its Secretary-General and had become editor-in-chief of the party's paper Al-Liwa’ as well as of other newspapers, including Al-Jami’a Al-Islamiyya. In 1938, Abd al-Qadir was exiled and in 1939 fled to Iraq where he took part in the Rashid Ali al-Gaylani coup.

Muhammad Nimr al-Hawari, who had started his career as a devoted follower of Hajj Amin, broke with the influential Husayni family in the early 1940s. The British estimated the strength of the al-Najjada paramilitary scout movement, led by Al-Hawari, at 8,000 prior to 1947.

1937 Peel Report and its aftermath

The Nashashibis broke with the Arab High Committee and Hajj Amīn shortly after the contents of the Palestine Royal Commission report were released on 7 July 1937, announcing a territorial partition plan.

The split in the ranks of the Arab High Committee (this was nothing more than a group of "traditional notables") between rejectionists and pro Partitionists led to Hajj Amin taking control of the AHC and with the support of the Arab League, rejected the plan, however many Palestinians, principally Nashashibi clan and the Arab Palestinian Communist Party, accepted the plan.

Results

The revolt of 1936–1939 led to an imbalance of power between the Jewish community and the Palestinian Arab community, as the latter had been substantially disarmed.

1947–1948 war

Al-Qadir moved to Egypt in 1946, but secretly returned to Palestine to lead the Army of the Holy War (AHW) in January 1948, and was killed during hand-to-hand fighting against Haganah; where AHW captured Qastal Hill on the Tel Aviv–Jerusalem road, on 8 April 1948. al-Qadir's death was a factor in the loss of morale among his forces, Ghuri, who had no experience of military command was appointed as commander of the AHW. Fawzi al-Qawuqji, at the head of the Arab Liberation Army remained as the only prominent military commander.

1948–1964

In September 1948, the All-Palestine Government was proclaimed in Egyptian-controlled Gaza Strip, and immediately won the support of Arab League members except Jordan. Though jurisdiction of the Government was declared to cover the whole of the former Mandatory Palestine, its effective jurisdiction was limited to the Gaza Strip. The Prime Minister of the Gaza-seated administration was named Ahmed Hilmi Pasha, and the President was named Hajj Amin al-Husseini, former chairman of the Arab Higher Committee.

The All-Palestine Government however lacked any significant authority and was in fact seated in Cairo. In 1959 it was officially merged into the United Arab Republic by the decree of Nasser, crippling any Palestinian hope for self governance. With the establishment in 1948 of the State of Israel, along with the migration of the Palestinian exodus, the common experience of the Palestinian refugee Arabs was mirrored in a fading of Palestinian identity. The institutions of a Palestinian nationality emerged slowly in the Palestinian refugee diaspora. In 1950 Yasser Arafat founded Ittihad Talabat Filastin. After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, most of the Husseini clan relocated to Jordan and the Gulf States. Many family heads that remained in the Old City and the northern neighborhoods of East Jerusalem fled due to hostility with the Jordanian government, which controlled that part of the city; King Abdullah's assassin was a member of an underground Palestinian organization led by Daoud al-Husayni.

The Fatah movement, which espoused a Palestinian nationalist ideology in which Palestinians would be liberated by the actions of Palestinian Arabs, was founded in 1954 by members of the Palestinian diaspora—principally professionals working in the Gulf States who had been refugees in Gaza and had gone on to study in Cairo or Beirut. The founders included Yasser Arafat who was head of the General Union of Palestinian Students (GUPS) (1952–1956) in Cairo University, Salah Khalaf, Khalil al-Wazir, Khaled Yashruti was head of the GUPS in Beirut (1958–1962).

PLO until the First Intifada (1964–1988)

The Palestine Liberation Organisation was founded by a meeting of 422 Palestinian national figures in Jerusalem in May 1964, following an earlier decision of the Arab League, its goal was the "liberation" of "Palestine" with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate. The original PLO Charter (issued on 28 May 1964) stated that "Palestine with its boundaries that existed at the time of the British mandate is an integral regional unit" and sought to "prohibit... the existence and activity" of Zionism. The charter also called for a right of return and self-determination for Palestinians.

Defeat suffered by the Arab states in the June 1967 Six-Day War, brought the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip under Israeli military control.

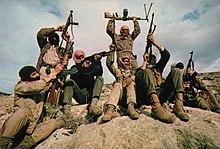

Yasser Arafat, claimed the Battle of Karameh (May 1968) as a victory (in Arabic, "karameh" means "dignity") and quickly became a Palestinian national hero; portrayed as one who dared to confront Israel. Masses of young Arabs joined the ranks of his group Fatah. Under pressure, Ahmad Shukeiri resigned from the PLO leadership and in July 1969, Fatah joined and soon controlled the PLO. The fierce Palestinian guerrilla fighting and the Jordanian Artillery bombardment forced the IDF withdrawal and gave the Palestinian Arabs an important morale boost. Israel was calling their army the indomitable army but this was the first chance for Arabs to claim victory after defeat in 1948, 1953, and 1967. After the battle, Fatah began to engage in communal projects to achieve popular affiliation. After the Battle of Karameh there was a subsequent increase in the PLO's strength. In 1974 the PLO called for an independent state in the territory of Mandate Palestine. The group used guerilla tactics to attack Israel from their bases in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, as well as from within the Gaza Strip and West Bank.

In 1988, the PLO officially endorsed a two-state solution, with Israel and Palestine living side by side contingent on specific terms such as making East Jerusalem capital of the Palestinian state and giving Palestinians the right of return to land occupied by Palestinians prior to the 1948 and 1967 wars with Israel.

First Intifada (1987–1993)

Local leadership vs. the PLO

The First Intifada (1987–1993) would prove another watershed in Palestinian nationalism, as it brought the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza to the forefront of the struggle. The Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU; Arabic al-Qiyada al Muwhhada) mobilised grassroots support for the uprising.

In 1987 The Intifada caught the (PLO) by surprise, the leadership abroad could only indirectly influence the events., A new local leadership, the UNLU, emerged, comprising many leading Palestinian factions. The disturbances initially spontaneous soon came under local leadership from groups and organizations loyal to the PLO that operated within the Occupied Territories; Fatah, the Popular Front, the Democratic Front and the Palestine Communist Party. The UNLU was the focus of the social cohesion that sustained the persistent disturbances.

After King Hussein of Jordan proclaimed the administrative and legal separation of the West Bank from Jordan in 1988, the UNLU organised to fill the political vacuum.

Emergence of Hamas

During the intifada Hamas replaced the monopoly of the PLO as sole representative of the Palestinian people.

Peace process

Some Israelis had become tired of the constant violence of the First Intifada, and many were willing to take risks for peace. Some wanted to realize the economic benefits in the new global economy. The Gulf War (1990–1991) did much to persuade Israelis that the defensive value of territory had been overstated, and that the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait psychologically reduced their sense of security.

A renewal of the Israeli–Palestinian quest for peace began at the end of the Cold War as the United States took the lead in international affairs. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Western observers were optimistic, as Francis Fukuyama wrote in an article, titled "The End of History". The hope was that the end of the Cold War heralded the beginning of a new international order. President George H. W. Bush, in a speech on 11 September 1990, spoke of a "rare opportunity" to move toward a "New world order" in which "the nations of the world, east and west, north and south, can prosper and live in harmony," adding that "today the new world is struggling to be born".

1993 Oslo Agreement

The demands of the local Palestinian and Israeli populations were somewhat differing from those of the Palestinian diaspora, which had constituted the main base of the PLO until then, in that they were primarily interested in independence, rather than refugee return. The resulting 1993 Oslo Agreement cemented the belief in a two-state solution in the mainstream Palestinian movement, as opposed to the PLO's original goal, a one-state solution which entailed the destruction of Israel and its replacement with a secular, democratic Palestinian state. The idea had first been seriously discussed in the 1970s, and gradually become the unofficial negotiating stance of the PLO leadership under Arafat, but it had still remained a taboo subject for most, until Arafat officially recognized Israel in 1988, under strong pressure from the United States. However, the belief in the ultimate necessity of Israel's destruction and/or its Zionist foundation (i.e., its existence as specifically Jewish state) is still advocated by many, such as the religiously motivated Hamas movement, although no longer by the PLO leadership.

Palestinian National Authority (1993)

In 1993, with the transfer of increased control of Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem from Israel to the Palestinians, PLO chairman Yasser Arafat appointed Sulaiman Ja'abari as Grand Mufti. When he died in 1994, Arafat appointed Ekrima Sa'id Sabri. Sabri was removed in 2006 by Palestinian National Authority president Mahmoud Abbas, who was concerned that Sabri was involved too heavily in political matters. Abbas appointed Muhammad Ahmad Hussein, who was perceived as a political moderate.

Goals

Palestinian statehood

Proposals for a Palestinian state refer to the proposed establishment of an independent state for the Palestinian people in Palestine on land that was occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War of 1967 and prior to that year by Egypt (Gaza) and by Jordan (West Bank). The proposals include the Gaza Strip, which is controlled by the Hamas faction of the Palestinian National Authority, the West Bank, which is administered by the Fatah faction of the Palestinian National Authority, and East Jerusalem which is controlled by Israel under a claim of sovereignty.

From the river to the sea

"From the river to the sea" is, and forms part of, a popular Palestinian political slogan. It references the land which lies between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea and has been frequently used in statements by Arab leaders. It is also chanted at pro-Palestinian protests and demonstrations, where it is often followed or preceded by the phrase "Palestine will be free".

"Palestine from the river to the sea" was claimed as Palestine by the PLO from its establishment in 1964 until the signing of the Oslo Accords. The PLO claim was originally set on areas, controlled by the State of Israel prior to 1967 War, meaning the combined Coastal Plain, Galilee, Yizrael Valley, Arava Valley, and Negev Desert but excluding West Bank (controlled then by Jordan) and Gaza Strip (occupied between 1959 and 1967 by Egypt). In a slightly different fashion, "Palestine from the river to the sea" is still claimed by Hamas referring to all areas of former Mandatory Palestine.

Competing national, political, and religious loyalties

Pan-Arabism

Some groups within the PLO hold a more pan-Arabist view than Fatah, and Fatah itself has never renounced Arab nationalism in favour of a strictly Palestinian nationalist ideology. Some of the pan-Arabist members justifying their views by claiming that the Palestinian struggle must be the spearhead of a wider, pan-Arab movement. For example, the Marxist PFLP viewed the "Palestinian revolution" as the first step to Arab unity as well as inseparable from a global anti-imperialist struggle. This said, however, there seems to be a general consensus among the main Palestinian factions that national liberation takes precedence over other loyalties, including Pan-Arabism, Islamism and proletarian internationalism.

Pan-Islamism

In a later repetition of these developments, the pan-Islamic sentiments embodied by the Muslim Brotherhood and other religious movements, would similarly provoke conflict with Palestinian nationalism. About 90% of Palestinians are Sunni Muslims, and while never absent from the rhetoric and thinking of the secularist PLO factions, Islamic political doctrines, or Islamism, did not become a large part of the Palestinian movement until the 1980s rise of Hamas.

By early Islamic thinkers, nationalism had been viewed as an ungodly ideology, substituting "the nation" for God as an object of worship and reverence. The struggle for Palestine was viewed exclusively through a religious prism, as a struggle to retrieve Muslim land and the holy places of Jerusalem. However, later developments, not least as a result of Muslim sympathy with the Palestinian struggle, led to many Islamic movements accepting nationalism as a legitimate ideology. In the case of Hamas, the Palestinian offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, Palestinian nationalism has almost completely fused with the ideologically pan-Islamic sentiments originally held by the Islamists.