| UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (II) | |

|---|---|

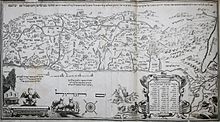

UNSCOP (3 September 1947; see green line) and UN Ad Hoc Committee (25 November 1947) partition plans. The UN Ad Hoc Committee proposal was voted on in the resolution. | |

| Date | 29 November 1947 |

| Meeting no. | 128 |

| Code | A/RES/181(II) (Document) |

Voting summary |

|

| Result | Adopted |

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Resolution 181 (II).

The resolution recommended the creation of independent Arab and Jewish States linked economically and a Special International Regime for the city of Jerusalem and its surroundings. The Arab state was to have a territory of 11,100 square kilometres or 42%, the Jewish state a territory of 14,100 square kilometres or 56%, while the remaining 2%—comprising the cities of Jerusalem, Bethlehem and the adjoning area—would become an international zone. The Partition Plan, a four-part document attached to the resolution, provided for the termination of the Mandate, the gradual withdrawal of British armed forces and the delineation of boundaries between the two States and Jerusalem. Part I of the Plan stipulated that the Mandate would be terminated as soon as possible and the United Kingdom would withdraw no later than 1 August 1948. The new states would come into existence two months after the withdrawal, but no later than 1 October 1948. The Plan sought to address the conflicting objectives and claims of two competing movements, Palestinian nationalism and Jewish nationalism, or Zionism.The Plan also called for Economic Union between the proposed states, and for the protection of religious and minority rights. Jewish organizations collaborated with UNSCOP during the deliberations, and the Palestinian Arab leadership boycotted it.

The plan’s detractors considered the proposed plan to be pro-Zionist, with 56% of the land allocated to the Jewish state although the Palestinian Arab population numbered twice the Jewish population. The plan was celebrated by most Jews in Palestine and reluctantly accepted by the Jewish Agency for Palestine with misgivings. Zionist leaders, in particular David Ben-Gurion, viewed the acceptance of the plan as a tactical step and a stepping stone to future territorial expansion over all of Palestine. The Arab Higher Committee, the Arab League and other Arab leaders and governments rejected it on the basis that in addition to the Arabs forming a two-thirds majority, they owned a majority of the lands. They also indicated an unwillingness to accept any form of territorial division, arguing that it violated the principles of national self-determination in the UN Charter which granted people the right to decide their own destiny. They announced their intention to take all necessary measures to prevent the implementation of the resolution. Subsequently, a civil war broke out in Palestine, and the plan was not implemented.

Background

The British administration was formalized by the League of Nations under the Palestine Mandate in 1923, as part of the Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire following World War I. The Mandate reaffirmed the 1917 British commitment to the Balfour Declaration, for the establishment in Palestine of a "National Home" for the Jewish people, with the prerogative to carry it out. A British census of 1918 estimated 700,000 Arabs and 56,000 Jews.

In 1937, following a six-month-long Arab General Strike and armed insurrection which aimed to pursue national independence and secure the country from foreign control, the British established the Peel Commission. The Commission concluded that the Mandate had become unworkable, and recommended partition into an Arab state linked to Transjordan; a small Jewish state; and a mandatory zone. To address problems arising from the presence of national minorities in each area, it suggested a land and population transfer involving the transfer of some 225,000 Arabs living in the envisaged Jewish state and 1,250 Jews living in a future Arab state, a measure deemed compulsory "in the last resort". To address any economic problems, the Plan proposed avoiding interfering with Jewish immigration, since any interference would be liable to produce an "economic crisis", most of Palestine's wealth coming from the Jewish community. To solve the predicted annual budget deficit of the Arab State and reduction in public services due to loss of tax from the Jewish state, it was proposed that the Jewish state pay an annual subsidy to the Arab state and take on half of the latter's deficit. The Palestinian Arab leadership rejected partition as unacceptable, given the inequality in the proposed population exchange and the transfer of one-third of Palestine, including most of its best agricultural land, to recent immigrants. The Jewish leaders, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, persuaded the Zionist Congress to lend provisional approval to the Peel recommendations as a basis for further negotiations. In a letter to his son in October 1937, Ben-Gurion explained that partition would be a first step to "possession of the land as a whole". The same sentiment, that acceptance of partition was a temporary measure beyond which the Palestine would be "redeemed ... in its entirety," was recorded by Ben-Gurion on other occasions, such as at a meeting of the Jewish Agency executive in June 1938, as well as by Chaim Weizmann.

The British Woodhead Commission was set up to examine the practicality of partition. The Peel plan was rejected and two possible alternatives were considered. In 1938, the British government issued a policy statement declaring that "the political, administrative and financial difficulties involved in the proposal to create independent Arab and Jewish States inside Palestine are so great that this solution of the problem is impracticable". Representatives of Arabs and Jews were invited to London for the St. James Conference, which proved unsuccessful.

With World War II looming, British policies were influenced by a desire to win Arab world support and could ill afford to engage with another Arab uprising. The MacDonald White Paper of May 1939 declared that it was "not part of [the British government's] policy that Palestine should become a Jewish State", sought to limit Jewish immigration to Palestine and restricted Arab land sales to Jews. However, the League of Nations commission held that the White Paper was in conflict with the terms of the Mandate as put forth in the past. The outbreak of the Second World War suspended any further deliberations. The Jewish Agency hoped to persuade the British to restore Jewish immigration rights, and cooperated with the British in the war against Fascism. Aliyah Bet was organized to spirit Jews out of Nazi controlled Europe, despite the British prohibitions. The White Paper also led to the formation of Lehi, a small Jewish organization which opposed the British.

After World War II, in August 1945 President Truman asked for the admission of 100,000 Holocaust survivors into Palestine but the British maintained limits on Jewish immigration in line with the 1939 White Paper. The Jewish community rejected the restriction on immigration and organized an armed resistance. These actions and United States pressure to end the anti-immigration policy led to the establishment of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. In April 1946, the Committee reached a unanimous decision for the immediate admission of 100,000 Jewish refugees from Europe into Palestine, rescission of the white paper restrictions of land sale to Jews, that the country be neither Arab nor Jewish, and the extension of U.N. Trusteeship. The U.S. endorsed the Commission's findings concerning Jewish immigration and land purchase restrictions, while the British made their agreement to implementation conditional on U.S. assistance in case of another Arab revolt. In effect, the British continued to carry out their White Paper policy. The recommendations triggered violent demonstrations in the Arab states, and calls for a Jihad and an annihilation of all European Jews in Palestine.

United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP)

Under the terms of League of Nations A-class mandates each such mandatory territory was to become a sovereign state on termination of its mandate. By the end of World War II, this occurred with all such mandates except Palestine; however, the League of Nations itself lapsed in 1946, leading to a legal quandary. In February 1947, Britain announced its intent to terminate the Mandate for Palestine, referring the matter of the future of Palestine to the United Nations. According to William Roger Louis, British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin's policy was premised on the idea that an Arab majority would carry the day, which met difficulties with Harry S. Truman who, sensitive to Zionist electoral pressures in the United States, pressed for a British-Zionist compromise. In May, the UN formed the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) to prepare a report on recommendations for Palestine. The Jewish Agency pressed for Jewish representation and the exclusion of both Britain and Arab countries on the Committee, sought visits to camps where Holocaust survivors were interned in Europe as part of UNSCOP's brief, and in May won representation on the Political Committee. The Arab states, convinced statehood had been subverted, and that the transition of authority from the League of Nations to the UN was questionable in law, wished the issues to be brought before an International Court, and refused to collaborate with UNSCOP, which had extended an invitation for liaison also to the Arab Higher Committee. In August, after three months of conducting hearings and a general survey of the situation in Palestine, a majority report of the committee recommended that the region be partitioned into an Arab state and a Jewish state, which should retain an economic union. An international regime was envisioned for Jerusalem.

The Arab delegations at the UN had sought to keep separate the issue of Palestine from the issue of Jewish refugees in Europe. During their visit, UNSCOP members were shocked by the extent of Lehi and Irgun violence, then at its apogee, and by the elaborate military presence attested by endemic barb-wire, searchlights, and armoured-car patrols. Committee members also witnessed the SS Exodus affair in Haifa and could hardly have remained unaffected by it. On concluding their mission, they dispatched a subcommittee to investigate Jewish refugee camps in Europe. The incident is mentioned in the report in relation to Jewish distrust and resentment concerning the British enforcement of the 1939 White Paper.

UNSCOP report

On 3 September 1947, the Committee reported to the General Assembly. CHAPTER V: PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS (I), Section A of the Report contained eleven proposed recommendations (I – XI) approved unanimously. Section B contained one proposed recommendation approved by a substantial majority dealing with the Jewish problem in general (XI). CHAPTER VI: PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS (II) contained a Plan of Partition with Economic Union to which seven members of the Committee (Canada, Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, the Netherlands, Peru, Sweden and Uruguay), expressed themselves in favour. CHAPTER VII RECOMMENDATIONS (III) contained a comprehensive proposal that was voted upon and supported by three members (India, Iran, and Yugoslavia) for a Federal State of Palestine. Australia abstained. In CHAPTER VIII a number of members of the Committee expressed certain reservations and observations.

Proposed partition

The report of the majority of the Committee (CHAPTER VI) envisaged the division of Palestine into three parts: an Arab State, a Jewish State and the City of Jerusalem, linked by extraterritorial crossroads. The proposed Arab State would include the central and part of western Galilee, with the town of Acre, the hill country of Samaria and Judea, an enclave at Jaffa, and the southern coast stretching from north of Isdud (now Ashdod) and encompassing what is now the Gaza Strip, with a section of desert along the Egyptian border. The proposed Jewish State would include the fertile Eastern Galilee, the Coastal Plain, stretching from Haifa to Rehovot and most of the Negev desert, including the southern outpost of Umm Rashrash (now Eilat). The Jerusalem Corpus Separatum included Bethlehem and the surrounding areas.

The primary objectives of the majority of the Committee were political division and economic unity between the two groups. The Plan tried its best to accommodate as many Jews as possible into the Jewish State. In many specific cases, this meant including areas of Arab majority (but with a significant Jewish minority) in the Jewish state. Thus the Jewish State would have an overall large Arab minority. Areas that were sparsely populated (like the Negev desert), were also included in the Jewish state to create room for immigration. According to the plan, Jews and Arabs living in the Jewish state would become citizens of the Jewish state and Jews and Arabs living in the Arab state would become citizens of the Arab state.

By virtue of Chapter 3, Palestinian citizens residing in Palestine outside the City of Jerusalem, as well as Arabs and Jews who, not holding Palestinian citizenship, resided in Palestine outside the City of Jerusalem would, upon the recognition of independence, become citizens of the State in which they were resident and enjoy full civil and political rights.

Population of Palestine by religions in 1946: Moslems — 1,076,783; Jews — 608,225; Christians — 145,063; Others — 15,488; Total — 1,845,559.

On this basis, the population at the end of 1946 was estimated as follows: Arabs — 1,203,000; Jews — 608,000; others — 35,000; Total — 1,846,000.

The Plan would have had the following demographics (data based on 1945).

| Territory | Arab and other population | % Arab and other | Jewish population | % Jewish | Total population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arab State | 725,000 | 99% | 10,000 | 1% | 735,000 | |

| Jewish State | 407,000 | 45% | 498,000 | 55% | 905,000 | |

| International | 105,000 | 51% | 100,000 | 49% | 205,000 | |

| Total | 1,237,000 | 67% | 608,000 | 33% | 1,845,000 | |

| Data from the Report of UNSCOP: 3 September 1947: CHAPTER 4: A COMMENTARY ON PARTITION | ||||||

In addition there would be in the Jewish State about 90,000 Bedouins, cultivators and stock owners who seek grazing further afield in dry seasons.

The land allocated to the Arab State in the final plan included about 43% of Mandatory Palestine and consisted of all of the highlands, except for Jerusalem, plus one-third of the coastline. The highlands contain the major aquifers of Palestine, which supplied water to the coastal cities of central Palestine, including Tel Aviv. The Jewish State allocated to the Jews, who constituted a third of the population and owned about 7% of the land, was to receive 56% of Mandatory Palestine, a slightly larger area to accommodate the increasing numbers of Jews who would immigrate there. The Jewish State included three fertile lowland plains – the Sharon on the coast, the Jezreel Valley and the upper Jordan Valley. The bulk of the proposed Jewish State's territory, however, consisted of the Negev Desert, which was mostly not suitable for agriculture, nor for urban development at that time. The Jewish State would also be given sole access to the Sea of Galilee, crucial for its water supply, and the economically important Red Sea.

The committee voted for the plan, 25 to 13 (with 17 abstentions and 2 absentees) on 25 November 1947 and the General Assembly was called back into a special session to vote on the proposal. Various sources noted that this was one vote short of the two-thirds majority required in the General Assembly.

Ad hoc Committee

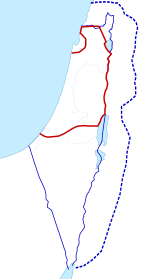

Boundaries defined in the 1947 UN Partition Plan for Palestine:

Armistice Demarcation Lines of 1949 (Green Line):

On 23 September 1947 the General Assembly established the Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question to consider the UNSCOP report. Representatives of the Arab Higher Committee and Jewish Agency were invited and attended.

During the committee's deliberations, the British government endorsed the report's recommendations concerning the end of the mandate, independence, and Jewish immigration. However, the British did "not feel able to implement" any agreement unless it was acceptable to both the Arabs and the Jews, and asked that the General Assembly provide an alternative implementing authority if that proved to be the case.

The Arab Higher Committee rejected both the majority and minority recommendations within the UNSCOP report. They "concluded from a survey of Palestine history that Zionist claims to that country had no legal or moral basis". The Arab Higher Committee argued that only an Arab State in the whole of Palestine would be consistent with the UN Charter.

The Jewish Agency expressed support for most of the UNSCOP recommendations, but emphasized the "intense urge" of the overwhelming majority of Jewish displaced persons to proceed to Palestine. The Jewish Agency criticized the proposed boundaries, especially in the Western Galilee and Western Jerusalem (outside of the old city), arguing that these should be included in the Jewish state. However, they agreed to accept the plan if "it would make possible the immediate re-establishment of the Jewish State with sovereign control of its own immigration."

Arab states requested representation on the UN ad hoc subcommittees of October 1947, but were excluded from Subcommittee One, which had been delegated the specific task of studying and, if thought necessary, modifying the boundaries of the proposed partition.

Sub-Committee 2

The Sub-Committee 2, set up on 23 October 1947 to draw up a detailed plan based on proposals of Arab states presented its report within a few weeks.

Based on a reproduced British report, the Sub-Committee 2 criticised the UNSCOP report for using inaccurate population figures, especially concerning the Bedouin population. The British report, dated 1 November 1947, used the results of a new census in Beersheba in 1946 with additional use of aerial photographs, and an estimate of the population in other districts. It found that the size of the Bedouin population was greatly understated in former enumerations. In Beersheba, 3,389 Bedouin houses and 8,722 tents were counted. The total Bedouin population was estimated at approximately 127,000; only 22,000 of them normally resident in the Arab state under the UNSCOP majority plan. The British report stated:

the term Beersheba Bedouin has a meaning more definite than one would expect in the case of a nomad population. These tribes, wherever they are found in Palestine, will always describe themselves as Beersheba tribes. Their attachment to the area arises from their land rights there and their historic association with it.

In respect of the UNSCOP report, the Sub-Committee concluded that the earlier population "estimates must, however, be corrected in the light of the information furnished to the Sub-Committee by the representative of the United Kingdom regarding the Bedouin population. According to the statement, 22,000 Bedouins may be taken as normally residing in the areas allocated to the Arab State under the UNSCOP's majority plan, and the balance of 105,000 as resident in the proposed Jewish State. It will thus be seen that the proposed Jewish State will contain a total population of 1,008,800, consisting of 509,780 Arabs and 499,020 Jews. In other words, at the outset, the Arabs will have a majority in the proposed Jewish State."

The Sub-Committee 2 recommended to put the question of the Partition Plan before the International Court of Justice (Resolution No. I ). In respect of the Jewish refugees due to World War II, the Sub-Committee recommended to request the countries of which the refugees belonged to take them back as much as possible (Resolution No. II). The Sub-Committee proposed to establish a unitary state (Resolution No. III).

Boundary changes

The ad hoc committee made a number of boundary changes to the UNSCOP recommendations before they were voted on by the General Assembly.

The predominantly Arab city of Jaffa, previously located within the Jewish state, was constituted as an enclave of the Arab State. The boundary of the Arab state was modified to include Beersheba and a strip of the Negev desert along the Egyptian border, while a section of the Dead Sea shore and other additions were made to the Jewish State. The Jewish population in the revised Jewish State would be about half a million, compared to 450,000 Arabs.

The proposed boundaries would also have placed 54 Arab villages on the opposite side of the border from their farm land. In response, the United Nations Palestine Commission established in 1948 was empowered to modify the boundaries "in such a way that village areas as a rule will not be divided by state boundaries unless pressing reasons make that necessary". These modifications never occurred.

The vote

Passage of the resolution required a two-thirds majority of the valid votes, not counting abstaining and absent members, of the UN's then 57 member states. On 26 November, after filibustering by the Zionist delegation, the vote was postponed by three days. According to multiple sources, had the vote been held on the original set date, it would have received a majority, but less than the required two-thirds. Various compromise proposals and variations on a single state, including federations and cantonal systems were debated (including those previously rejected in committee). The delay was used by supporters of Zionism in New York to put extra pressure on states not supporting the resolution.

Reports of pressure for and against the Plan

Reports of pressure for the Plan

Zionists launched an intense White House lobby to have the UNSCOP plan endorsed, and the effects were not trivial. The Democratic Party, a large part of whose contributions came from Jews, informed Truman that failure to live up to promises to support the Jews in Palestine would constitute a danger to the party. The defection of Jewish votes in congressional elections in 1946 had contributed to electoral losses. Truman was, according to Roger Cohen, embittered by feelings of being a hostage to the lobby and its 'unwarranted interference', which he blamed for the contemporary impasse. When a formal American declaration in favour of partition was given on 11 October, a public relations authority declared to the Zionist Emergency Council in a closed meeting: 'under no circumstances should any of us believe or think we had won because of the devotion of the American Government to our cause. We had won because of the sheer pressure of political logistics that was applied by the Jewish leadership in the United States'. State Department advice critical of the controversial UNSCOP recommendation to give the overwhelmingly Arab town of Jaffa, and the Negev, to the Jews was overturned by an urgent and secret late meeting organized for Chaim Weizman with Truman, which immediately countermanded the recommendation. The United States initially refrained from pressuring smaller states to vote either way, but Robert A. Lovett reported that America's U.N. delegation's case suffered impediments from high pressure by Jewish groups, and that indications existed that bribes and threats were being used, even of American sanctions against Liberia and Nicaragua. When the UNSCOP plan failed to achieve the necessary majority on 25 November, the lobby 'moved into high gear' and induced the President to overrule the State Department, and let wavering governments know that the U.S. strongly desired partition.

Proponents of the Plan reportedly put pressure on nations to vote yes to the Partition Plan. A telegram signed by 26 US Senators with influence on foreign aid bills was sent to wavering countries, seeking their support for the partition plan. The US Senate was considering a large aid package at the time, including 60 million dollars to China. Many nations reported pressure directed specifically at them:

United States (Vote: For): President Truman

later noted, "The facts were that not only were there pressure

movements around the United Nations unlike anything that had been seen

there before, but that the White House, too, was subjected to a constant

barrage. I do not think I ever had as much pressure and propaganda

aimed at the White House as I had in this instance. The persistence of a

few of the extreme Zionist leaders—actuated by political motives and

engaging in political threats—disturbed and annoyed me."

United States (Vote: For): President Truman

later noted, "The facts were that not only were there pressure

movements around the United Nations unlike anything that had been seen

there before, but that the White House, too, was subjected to a constant

barrage. I do not think I ever had as much pressure and propaganda

aimed at the White House as I had in this instance. The persistence of a

few of the extreme Zionist leaders—actuated by political motives and

engaging in political threats—disturbed and annoyed me." India (Vote: Against): Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

spoke with anger and contempt for the way the UN vote had been lined

up. He said the Zionists had tried to bribe India with millions and at

the same time his sister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, the Indian ambassador to the UN, had received daily warnings that her life was in danger unless "she voted right".

Pandit occasionally hinted that something might change in favour of the

Zionists. But another Indian delegate, Kavallam Pannikar, said that

India would vote for the Arab side, because of their large Muslim minority, although they knew that the Jews had a case.

India (Vote: Against): Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

spoke with anger and contempt for the way the UN vote had been lined

up. He said the Zionists had tried to bribe India with millions and at

the same time his sister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, the Indian ambassador to the UN, had received daily warnings that her life was in danger unless "she voted right".

Pandit occasionally hinted that something might change in favour of the

Zionists. But another Indian delegate, Kavallam Pannikar, said that

India would vote for the Arab side, because of their large Muslim minority, although they knew that the Jews had a case. Liberia (Vote: For): Liberia's Ambassador to the United States complained that the US delegation threatened aid cuts to several countries. Harvey S. Firestone Jr., President of Firestone Natural Rubber Company, with major holdings in the country, also pressured the Liberian government.

Liberia (Vote: For): Liberia's Ambassador to the United States complained that the US delegation threatened aid cuts to several countries. Harvey S. Firestone Jr., President of Firestone Natural Rubber Company, with major holdings in the country, also pressured the Liberian government. Philippines (Vote: For): In the days before the vote, Philippines representative General Carlos P. Romulo

stated "We hold that the issue is primarily moral. The issue is whether

the United Nations should accept responsibility for the enforcement of a

policy which is clearly repugnant to the valid nationalist aspirations

of the people of Palestine. The Philippines Government holds that the

United Nations ought not to accept such responsibility." After a phone

call from Washington, the representative was recalled and the

Philippines' vote changed.

Philippines (Vote: For): In the days before the vote, Philippines representative General Carlos P. Romulo

stated "We hold that the issue is primarily moral. The issue is whether

the United Nations should accept responsibility for the enforcement of a

policy which is clearly repugnant to the valid nationalist aspirations

of the people of Palestine. The Philippines Government holds that the

United Nations ought not to accept such responsibility." After a phone

call from Washington, the representative was recalled and the

Philippines' vote changed. Haiti (Vote: For): The promise of a five million dollar loan may or may not have secured Haiti's vote for partition.

Haiti (Vote: For): The promise of a five million dollar loan may or may not have secured Haiti's vote for partition. France (Vote: For): Shortly before the vote, France's delegate to the United Nations was visited by Bernard Baruch,

a long-term Jewish supporter of the Democratic Party who, during the

recent world war, had been an economic adviser to President Roosevelt,

and had latterly been appointed by President Truman as United States

ambassador to the newly created UN Atomic Energy Commission. He was,

privately, a supporter of the Irgun

and its front organization, the American League for a Free Palestine.

Baruch implied that a French failure to support the resolution might

block planned American aid to France, which was badly needed for

reconstruction, French currency reserves being exhausted and its balance

of payments heavily in deficit. Previously, to avoid antagonising its

Arab colonies, France had not publicly supported the resolution. After

considering the danger of American aid being withheld, France finally

voted in favour of it. So, too, did France's neighbours, Belgium,

Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

France (Vote: For): Shortly before the vote, France's delegate to the United Nations was visited by Bernard Baruch,

a long-term Jewish supporter of the Democratic Party who, during the

recent world war, had been an economic adviser to President Roosevelt,

and had latterly been appointed by President Truman as United States

ambassador to the newly created UN Atomic Energy Commission. He was,

privately, a supporter of the Irgun

and its front organization, the American League for a Free Palestine.

Baruch implied that a French failure to support the resolution might

block planned American aid to France, which was badly needed for

reconstruction, French currency reserves being exhausted and its balance

of payments heavily in deficit. Previously, to avoid antagonising its

Arab colonies, France had not publicly supported the resolution. After

considering the danger of American aid being withheld, France finally

voted in favour of it. So, too, did France's neighbours, Belgium,

Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Venezuela (Vote: For): Carlos Eduardo Stolk, Chairman of the Delegation of Venezuela, voted in favor of Resolution 181 .

Venezuela (Vote: For): Carlos Eduardo Stolk, Chairman of the Delegation of Venezuela, voted in favor of Resolution 181 . Cuba (Vote: Against):

The Cuban delegation stated they would vote against partition "in spite

of pressure being brought to bear against us" because they could not be

party to coercing the majority in Palestine.

Cuba (Vote: Against):

The Cuban delegation stated they would vote against partition "in spite

of pressure being brought to bear against us" because they could not be

party to coercing the majority in Palestine. Siam

(Absent): The credentials of the Siamese delegations were cancelled

after Siam voted against partition in committee on 25 November.

Siam

(Absent): The credentials of the Siamese delegations were cancelled

after Siam voted against partition in committee on 25 November.

There is also some evidence that Sam Zemurray put pressure on several "banana republics" to change their votes.

Reports of pressure against the Plan

According to Benny Morris, Wasif Kamal, an Arab Higher Committee official, tried to bribe a delegate to the United Nations, perhaps a Russian.

A number of Arab leaders argued against the partition proposal on the grounds that it endangered the Jews of Arab countries.

- A few months before the UN vote on partition of Palestine, Iraq's prime minister Nuri al-Said told British diplomat Douglas Busk that he had nothing against the Iraqi Jews, who were a long established and useful community. However, if the United Nations solution was not satisfactory, the Arab League might decide on severe measures against the Jews in Arab countries, and he would be unable to resist the proposal.

- At the 30th Meeting of the UN Ad Hoc Committee on Palestine on 24 November 1947, the head of the Egyptian delegate, Heykal Pasha, said that although there was no animosity against the Jews in Arab countries, nobody could prevent disorders if a Jewish state was established. Riots could break out which governments could not control, endangering the lives of Jews and creating an antisemitism difficult to root out. The UN, in Heykal's view, should consider the welfare of all Jews and not just the wishes of the Zionists.

- In a speech at the General Assembly Hall at Flushing Meadow, New York, on Friday, 28 November 1947, Iraq’s Foreign Minister, Fadel Jamall, included the following statement: "Partition imposed against the will of the majority of the people will jeopardize peace and harmony in the Middle East. Not only the uprising of the Arabs of Palestine is to be expected, but the masses in the Arab world cannot be restrained. The Arab-Jewish relationship in the Arab world will greatly deteriorate. There are more Jews in the Arab world outside of Palestine than there are in Palestine. In Iraq alone, we have about one hundred and fifty thousand Jews who share with Moslems and Christians all the advantages of political and economic rights. Harmony prevails among Moslems, Christians and Jews. But any injustice imposed upon the Arabs of Palestine will disturb the harmony among Jews and non-Jews in Iraq; it will breed inter-religious prejudice and hatred."

The Arab states warned the Western Powers that endorsement of the partition plan might be met by either or both an oil embargo and realignment of the Arab states with the Soviet Bloc.

Final vote

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly voted 33 to 13, with 10 abstentions and 1 absent, in favour of the modified Partition Plan. The final vote, consolidated here by modern United Nations Regional Groups rather than contemporary groupings, was as follows:

In favour (33 countries, 72% of total votes)

Latin American and Caribbean (13 countries):

Western European and Others (8 countries):

Eastern European (5 countries):

African (2 countries):

Asia-Pacific (3 countries)

North America (2 countries)

Against (13 countries, 28% of total votes)

Asia-Pacific (9 countries, primarily Middle East sub-area):

Western European and Others (2 countries):

African (1 country):

Latin American and Caribbean (1 country):

Abstentions (10 countries)

Latin American and Caribbean (6 countries):

Asia-Pacific (1 country):

African (1 country):

Western European and Others (1 country):

Eastern European (1 country):

Absent (1 country)

Asia-Pacific (1 country):

Votes by modern region

If analysed by the modern composition of what later came to be known as the United Nations Regional Groups showed relatively aligned voting styles in the final vote. This, however, does not reflect the regional grouping at the time, as a major reshuffle of regional grouping occurred in 1966. All Western nations voted for the resolution, with the exception of the United Kingdom (the Mandate holder), Greece and Turkey. The Soviet bloc also voted for partition, with the exception of Yugoslavia, which was to be expelled from Cominform the following year. The majority of Latin American nations following Brazilian leadership, voted for partition, with a sizeable minority abstaining. Asian countries (primarily Middle Eastern countries) voted against partition, with the exception of the Philippines.

| Regional Group | Members in UNGA181 vote | UNGA181 For | UNGA181 Against | UNGA181 Abstained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Asia-Pacific | 11 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| Eastern European | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| LatAm and Caribb. | 20 | 13 | 1 | 6 |

| Western Eur. & Others | 15 | 12 | 2 | 1 |

| Total UN members | 56 | 33 | 13 | 10 |

Reactions

Jews

Jews gathered in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to celebrate the U.N. resolution during the whole night after the vote. Great bonfires blazed at Jewish collective farms in the north. Many big cafes in Tel Aviv served free champagne. Mainstream Zionist leaders emphasized the "heavy responsibility" of building a modern Jewish State, and committed to working towards a peaceful coexistence with the region's other inhabitants: Jewish groups in the United States hailed the action by the United Nations. Most welcomed the Palestine Plan but some felt it did not settle the problem.

Some Revisionist Zionists rejected the partition plan as a renunciation of legitimately Jewish national territory. The Irgun Tsvai Leumi, led by Menachem Begin, and the Lehi (also known as the Stern Group or Gang), the two Revisionist-affiliated underground organisations which had been fighting against both the British and Arabs, stated their opposition. Begin warned that the partition would not bring peace because the Arabs would also attack the small state and that "in the war ahead we'll have to stand on our own, it will be a war on our existence and future." He also stated that "the bisection of our homeland is illegal. It will never be recognized." Begin was sure that the creation of a Jewish state would make territorial expansion possible, "after the shedding of much blood."

Some Post-Zionist scholars endorse Simha Flapan's view that it is a myth that Zionists accepted the partition as a compromise by which the Jewish community abandoned ambitions for the whole of Palestine and recognized the rights of the Arab Palestinians to their own state. Rather, Flapan argued, acceptance was only a tactical move that aimed to thwart the creation of an Arab Palestinian state and, concomitantly, expand the territory that had been assigned by the UN to the Jewish state. Baruch Kimmerling has said that Zionists "officially accepted the partition plan, but invested all their efforts towards improving its terms and maximally expanding their boundaries while reducing the number of Arabs in them." Zionist leaders viewed the acceptance of the plan as a tactical step and a stepping stone to future territorial expansion over all of Palestine.

Addressing the Central Committee of the Histadrut (the Eretz Israel Workers Party) days after the UN vote to partition Palestine, Ben-Gurion expressed his apprehension, stating:

the total population of the Jewish State at the time of its establishment will be about one million, including almost 40% non-Jews. Such a [population] composition does not provide a stable basis for a Jewish State. This [demographic] fact must be viewed in all its clarity and acuteness. With such a [population] composition, there cannot even be absolute certainty that control will remain in the hands of the Jewish majority... There can be no stable and strong Jewish state so long as it has a Jewish majority of only 60%.

Ben-Gurion said "I know of no greater achievement by the Jewish people ... in its long history since it became a people."

Arabs

Arab leaders and governments rejected the plan of partition in the resolution and indicated that they would reject any other plan of partition. The Arab states' delegations declared immediately after the vote for partition that they would not be bound by the decision, and walked out accompanied by the Indian and Pakistani delegates.

They argued that it violated the principles of national self-determination in the UN charter which granted people the right to decide their own destiny. The Arab delegations to the UN issued a joint statement the day after that vote that stated: "the vote in regard to the Partition of Palestine has been given under great pressure and duress, and that this makes it doubly invalid."

On 16 February 1948, the UN Palestine Commission reported to the Security Council that: "Powerful Arab interests, both inside and outside Palestine, are defying the resolution of the General Assembly and are engaged in a deliberate effort to alter by force the settlement envisaged therein."

Arab states

A few weeks after UNSCOP released its report, Azzam Pasha, the General Secretary of the Arab League, told an Egyptian newspaper "Personally I hope the Jews do not force us into this war because it will be a war of elimination and it will be a dangerous massacre which history will record similarly to the Mongol massacre or the wars of the Crusades." (This statement from October 1947 has often been incorrectly reported as having been made much later on 15 May 1948.) Azzam told Alec Kirkbride "We will sweep them [the Jews] into the sea." Syrian president Shukri al-Quwatli told his people: "We shall eradicate Zionism."

King Farouk of Egypt told the American ambassador to Egypt that in the long run the Arabs would soundly defeat the Jews and drive them out of Palestine.

While Azzam Pasha repeated his threats of forceful prevention of partition, the first important Arab voice to support partition was the influential Egyptian daily Al Mokattam: "We stand for partition because we believe that it is the best final solution for the problem of Palestine... rejection of partition... will lead to further complications and will give the Zionists another space of time to complete their plans of defense and attack... a delay of one more year which would not benefit the Arabs but would benefit the Jews, especially after the British evacuation."

On 20 May 1948, Azzam told reporters "We are fighting for an Arab Palestine. Whatever the outcome the Arabs will stick to their offer of equal citizenship for Jews in Arab Palestine and let them be as Jewish as they like. In areas where they predominate they will have complete autonomy."

The Arab League said that some of the Jews would have to be expelled from a Palestinian Arab state.

Abdullah appointed Ibrahim Hashem Pasha as Military Governor of the Arab areas occupied by troops of the Transjordan Army. He was a former prime minister of Transjordan who supported partition of Palestine as proposed by the Peel Commission and the United Nations.

Arabs in Palestine

Haj Amin al-Husseini said in March 1948 to an interviewer from the Jaffa daily Al Sarih that the Arabs did not intend merely to prevent partition but "would continue fighting until the Zionists were annihilated."

Zionists attributed Arab rejection of the plan to mere intransigence. Palestinian Arabs opposed the very idea of partition but reiterated that this partition plan was unfair: the majority of the land (56%) would go to a Jewish state, when Jews at that stage legally owned only 6–7% of it and remained a minority of the population (33% in 1946). There were also disproportionate allocations under the plan and the area under Jewish control contained 45% of the Palestinian population. The proposed Arab state was only given 45% of the land, much of which was unfit for agriculture. Jaffa, though geographically separated, was to be part of the Arab state. However, most of the proposed Jewish state was the Negev desert. The plan allocated to the Jewish State most of the Negev desert that was sparsely populated and unsuitable for agriculture but also a "vital land bridge protecting British interests from the Suez Canal to Iraq"

Few Palestinian Arabs joined the Arab Liberation Army because they suspected that the other Arab States did not plan on an independent Palestinian state. According to Ian Bickerton, for that reason many of them favored partition and indicated a willingness to live alongside a Jewish state. He also mentions that the Nashashibi family backed King Abdullah and union with Transjordan.

The Arab Higher Committee demanded that in a Palestinian Arab state, the majority of the Jews should not be citizens (those who had not lived in Palestine before the British Mandate).

According to Musa Alami, the mufti would agree to partition if he were promised that he would rule the future Arab state.

The Arab Higher Committee responded to the partition resolution and declared a three-day general strike in Palestine to begin the following day.

British government

When Bevin received the partition proposal, he promptly ordered for it not to be imposed on the Arabs. The plan was vigorously debated in the British parliament.

In a British cabinet meeting at 4 December 1947, it was decided that the Mandate would end at midnight 14 May 1948, the complete withdrawal by 1 August 1948, and Britain would not enforce the UN partition plan. On 11 December 1947, the British government publicly announced these plans. During the period in which the British withdrawal was completed, Britain refused to share the administration of Palestine with a proposed UN transition regime, to allow the UN Palestine Commission to establish a presence in Palestine earlier than a fortnight before the end of the Mandate, to allow the creation of official Jewish and Arab militias or to assist in smoothly handing over territory or authority to any successor.

United States government

The United States declined to recognize the All-Palestine government in Gaza by explaining that it had accepted the UN Mediator's proposal. The Mediator had recommended that Palestine, as defined in the original Mandate including Transjordan, might form a union. Bernadotte's diary said the Mufti had lost credibility on account of his unrealistic predictions regarding the defeat of the Jewish militias. Bernadotte noted "It would seem as though in existing circumstances most of the Palestinian Arabs would be quite content to be incorporated in Transjordan."

Subsequent events

The Partition Plan with Economic Union was not realized in the days following 29 November 1947 resolution as envisaged by the General Assembly. It was followed by outbreaks of violence in Mandatory Palestine between Palestinian Jews and Arabs known as the 1947–48 Civil War. After Alan Cunningham, the High Commissioner of Palestine, left Jerusalem, on the morning of 14 May the British army left the city as well. The British left a power vacuum in Jerusalem and made no measures to establish the international regime in Jerusalem. At midnight on 14 May 1948, the British Mandate expired, and Britain disengaged its forces. Earlier in the evening, the Jewish People's Council had gathered at the Tel Aviv Museum (today known as Independence Hall), and approved a proclamation, declaring "the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Israel, to be known as the State of Israel". The 1948 Arab–Israeli War began with the invasion of, or intervention in, Palestine by the Arab States on 15 May 1948.

Resolution 181 as a legal basis for Palestinian statehood

In 1988, the Palestine Liberation Organization published the Palestinian Declaration of Independence relying on Resolution 181, arguing that the resolution continues to provide international legitimacy for the right of the Palestinian people to sovereignty and national independence. A number of scholars have written in support of this view.

A General Assembly request for an advisory opinion, Resolution ES-10/14 (2004), specifically cited resolution 181(II) as a "relevant resolution", and asked the International Court of Justice (ICJ) what are the legal consequences of the relevant Security Council and General Assembly resolutions. Judge Abdul Koroma explained the majority opinion: "The Court has also held that the right of self-determination as an established and recognized right under international law applies to the territory and to the Palestinian people. Accordingly, the exercise of such right entitles the Palestinian people to a State of their own as originally envisaged in resolution 181 (II) and subsequently confirmed." In response, Prof. Paul De Waart said that the Court put the legality of the 1922 League of Nations Palestine Mandate and the 1947 UN Plan of Partition beyond doubt once and for all.

Retrospect

In 2011, Mahmoud Abbas stated that the 1947 Arab rejection of United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a mistake he hoped to rectify.

Commemoration