A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input. An individual's construction of reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, and irrationality.

While cognitive biases may initially appear to be negative, some are adaptive. They may lead to more effective actions in a given context. Furthermore, allowing cognitive biases enables faster decisions which can be desirable when timeliness is more valuable than accuracy, as illustrated in heuristics. Other cognitive biases are a "by-product" of human processing limitations, resulting from a lack of appropriate mental mechanisms (bounded rationality), the impact of an individual's constitution and biological state (see embodied cognition), or simply from a limited capacity for information processing. Research suggests that cognitive biases can make individuals more inclined to endorsing pseudoscientific beliefs by requiring less evidence for claims that confirm their preconceptions. This can potentially distort their perceptions and lead to inaccurate judgments.

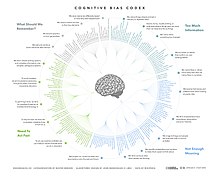

A continually evolving list of cognitive biases has been identified over the last six decades of research on human judgment and decision-making in cognitive science, social psychology, and behavioral economics. The study of cognitive biases has practical implications for areas including clinical judgment, entrepreneurship, finance, and management.

Overview

The notion of cognitive biases was introduced by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in 1972 and grew out of their experience of people's innumeracy, or inability to reason intuitively with the greater orders of magnitude. Tversky, Kahneman, and colleagues demonstrated several replicable ways in which human judgments and decisions differ from rational choice theory. Tversky and Kahneman explained human differences in judgment and decision-making in terms of heuristics. Heuristics involve mental shortcuts which provide swift estimates about the possibility of uncertain occurrences. Heuristics are simple for the brain to compute but sometimes introduce "severe and systematic errors." For example, the representativeness heuristic is defined as "The tendency to judge the frequency or likelihood" of an occurrence by the extent of which the event "resembles the typical case."

The "Linda Problem" illustrates the representativeness heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983). Participants were given a description of "Linda" that suggests Linda might well be a feminist (e.g., she is said to be concerned about discrimination and social justice issues). They were then asked whether they thought Linda was more likely to be (a) a "bank teller" or (b) a "bank teller and active in the feminist movement." A majority chose answer (b). Independent of the information given about Linda, though, the more restrictive answer (b) is under any circumstance statistically less likely than answer (a). This is an example of the "conjunction fallacy". Tversky and Kahneman argued that respondents chose (b) because it seemed more "representative" or typical of persons who might fit the description of Linda. The representativeness heuristic may lead to errors such as activating stereotypes and inaccurate judgments of others (Haselton et al., 2005, p. 726).

Critics of Kahneman and Tversky, such as Gerd Gigerenzer, alternatively argued that heuristics should not lead us to conceive of human thinking as riddled with irrational cognitive biases. They should rather conceive rationality as an adaptive tool, not identical to the rules of formal logic or the probability calculus. Nevertheless, experiments such as the "Linda problem" grew into heuristics and biases research programs, which spread beyond academic psychology into other disciplines including medicine and political science.

Types

Biases can be distinguished on a number of dimensions. Examples of cognitive biases include -

- Biases specific to groups (such as the risky shift) versus biases at the individual level.

- Biases that affect decision-making, where the desirability of options has to be considered (e.g., sunk costs fallacy).

- Biases, such as illusory correlation, that affect judgment of how likely something is or whether one thing is the cause of another.

- Biases that affect memory, such as consistency bias (remembering one's past attitudes and behavior as more similar to one's present attitudes).

- Biases that reflect a subject's motivation, for example, the desire for a positive self-image leading to egocentric bias and the avoidance of unpleasant cognitive dissonance.

Other biases are due to the particular way the brain perceives, forms memories and makes judgments. This distinction is sometimes described as "hot cognition" versus "cold cognition", as motivated reasoning can involve a state of arousal. Among the "cold" biases,

- some are due to ignoring relevant information (e.g., neglect of probability),

- some involve a decision or judgment being affected by irrelevant information (for example the framing effect where the same problem receives different responses depending on how it is described; or the distinction bias where choices presented together have different outcomes than those presented separately), and

- others give excessive weight to an unimportant but salient feature of the problem (e.g., anchoring).

As some biases reflect motivation specifically the motivation to have positive attitudes to oneself. It accounts for the fact that many biases are self-motivated or self-directed (e.g., illusion of asymmetric insight, self-serving bias). There are also biases in how subjects evaluate in-groups or out-groups; evaluating in-groups as more diverse and "better" in many respects, even when those groups are arbitrarily defined (ingroup bias, outgroup homogeneity bias).

Some cognitive biases belong to the subgroup of attentional biases, which refers to paying increased attention to certain stimuli. It has been shown, for example, that people addicted to alcohol and other drugs pay more attention to drug-related stimuli. Common psychological tests to measure those biases are the Stroop task and the dot probe task.

Individuals' susceptibility to some types of cognitive biases can be measured by the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) developed by Shane Frederick (2005).

List of biases

The following is a list of the more commonly studied cognitive biases:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Fundamental attribution error (FAE, aka correspondence bias) | Tendency to overemphasize personality-based explanations for behaviors observed in others. At the same time, individuals under-emphasize the role and power of situational influences on the same behavior. Edward E. Jones and Victor A. Harris' (1967) classic study illustrates the FAE. Despite being made aware that the target's speech direction (pro-Castro/anti-Castro) was assigned to the writer, participants ignored the situational pressures and attributed pro-Castro attitudes to the writer when the speech represented such attitudes. |

| Implicit bias (aka implicit stereotype, unconscious bias) | Tendency to attribute positive or negative qualities to a group of individuals. It can be fully non-factual or be an abusive generalization of a frequent trait in a group to all individuals of that group. |

| Priming bias | Tendency to be influenced by the first presentation of an issue to create our preconceived idea of it, which we then can adjust with later information. |

| Confirmation bias | Tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one's preconceptions, and discredit information that does not support the initial opinion. Related to the concept of cognitive dissonance, in that individuals may reduce inconsistency by searching for information which reconfirms their views (Jermias, 2001, p. 146). |

| Affinity bias | Tendency to be favorably biased toward people most like ourselves. |

| Self-serving bias | Tendency to claim more responsibility for successes than for failures. It may also manifest itself as a tendency for people to evaluate ambiguous information in a way beneficial to their interests. |

| Belief bias | Tendency to evaluate the logical strength of an argument based on current belief and perceived plausibility of the statement's conclusion. |

| Framing | Tendency to narrow the description of a situation in order to guide to a selected conclusion. The same primer can be framed differently and therefore lead to different conclusions. |

| Hindsight bias | Tendency to view past events as being predictable. Also called the "I-knew-it-all-along" effect. |

| Embodied cognition | Tendency to have selectivity in perception, attention, decision making, and motivation based on the biological state of the body. |

| Anchoring bias | The inability of people to make appropriate adjustments from a starting point in response to a final answer. It can lead people to make sub-optimal decisions. Anchoring affects decision making in negotiations, medical diagnoses, and judicial sentencing. |

| Status quo bias | Tendency to hold to the current situation rather than an alternative situation, to avoid risk and loss (loss aversion). In status quo bias, a decision-maker has the increased propensity to choose an option because it is the default option or status quo. Has been shown to affect various important economic decisions, for example, a choice of car insurance or electrical service. |

| Overconfidence effect | Tendency to overly trust one's own capability to make correct decisions. People tended to overrate their abilities and skills as decision makers. See also the Dunning–Kruger effect. |

| Physical attractiveness stereotype | The tendency to assume people who are physically attractive also possess other desirable personality traits. |

Practical significance

Many social institutions rely on individuals to make rational judgments.

The securities regulation regime largely assumes that all investors act as perfectly rational persons. In truth, actual investors face cognitive limitations from biases, heuristics, and framing effects.

A fair jury trial, for example, requires that the jury ignore irrelevant features of the case, weigh the relevant features appropriately, consider different possibilities open-mindedly and resist fallacies such as appeal to emotion. The various biases demonstrated in these psychological experiments suggest that people will frequently fail to do all these things. However, they fail to do so in systematic, directional ways that are predictable.

In some academic disciplines, the study of bias is very popular. For instance, bias is a wide spread and well studied phenomenon because most decisions that concern the minds and hearts of entrepreneurs are computationally intractable.

Cognitive biases can create other issues that arise in everyday life. One study showed the connection between cognitive bias, specifically approach bias, and inhibitory control on how much unhealthy snack food a person would eat. They found that the participants who ate more of the unhealthy snack food, tended to have less inhibitory control and more reliance on approach bias. Others have also hypothesized that cognitive biases could be linked to various eating disorders and how people view their bodies and their body image.

It has also been argued that cognitive biases can be used in destructive ways. Some believe that there are people in authority who use cognitive biases and heuristics in order to manipulate others so that they can reach their end goals. Some medications and other health care treatments rely on cognitive biases in order to persuade others who are susceptible to cognitive biases to use their products. Many see this as taking advantage of one's natural struggle of judgement and decision-making. They also believe that it is the government's responsibility to regulate these misleading ads.

Cognitive biases also seem to play a role in property sale price and value. Participants in the experiment were shown a residential property. Afterwards, they were shown another property that was completely unrelated to the first property. They were asked to say what they believed the value and the sale price of the second property would be. They found that showing the participants an unrelated property did have an effect on how they valued the second property.

Cognitive biases can be used in non-destructive ways. In team science and collective problem-solving, the superiority bias can be beneficial. It leads to a diversity of solutions within a group, especially in complex problems, by preventing premature consensus on suboptimal solutions. This example demonstrates how a cognitive bias, typically seen as a hindrance, can enhance collective decision-making by encouraging a wider exploration of possibilities.

Reducing

Because they cause systematic errors, cognitive biases cannot be compensated for using a wisdom of the crowd technique of averaging answers from several people. Debiasing is the reduction of biases in judgment and decision-making through incentives, nudges, and training. Cognitive bias mitigation and cognitive bias modification are forms of debiasing specifically applicable to cognitive biases and their effects. Reference class forecasting is a method for systematically debiasing estimates and decisions, based on what Daniel Kahneman has dubbed the outside view.

Similar to Gigerenzer (1996), Haselton et al. (2005) state the content and direction of cognitive biases are not "arbitrary" (p. 730). Moreover, cognitive biases can be controlled. One debiasing technique aims to decrease biases by encouraging individuals to use controlled processing compared to automatic processing. In relation to reducing the FAE, monetary incentives and informing participants they will be held accountable for their attributions have been linked to the increase of accurate attributions. Training has also shown to reduce cognitive bias. Carey K. Morewedge and colleagues (2015) found that research participants exposed to one-shot training interventions, such as educational videos and debiasing games that taught mitigating strategies, exhibited significant reductions in their commission of six cognitive biases immediately and up to 3 months later.

Cognitive bias modification refers to the process of modifying cognitive biases in healthy people and also refers to a growing area of psychological (non-pharmaceutical) therapies for anxiety, depression and addiction called cognitive bias modification therapy (CBMT). CBMT is sub-group of therapies within a growing area of psychological therapies based on modifying cognitive processes with or without accompanying medication and talk therapy, sometimes referred to as applied cognitive processing therapies (ACPT). Although cognitive bias modification can refer to modifying cognitive processes in healthy individuals, CBMT is a growing area of evidence-based psychological therapy, in which cognitive processes are modified to relieve suffering from serious depression, anxiety, and addiction. CBMT techniques are technology-assisted therapies that are delivered via a computer with or without clinician support. CBM combines evidence and theory from the cognitive model of anxiety, cognitive neuroscience, and attentional models.

Cognitive bias modification has also been used to help those with obsessive-compulsive beliefs and obsessive-compulsive disorder. This therapy has shown that it decreases the obsessive-compulsive beliefs and behaviors.

Common theoretical causes of some cognitive biases

Bias arises from various processes that are sometimes difficult to distinguish. These include:

- Bounded rationality — limits on optimization and rationality

- Evolutionary psychology — Remnants from evolutionary adaptive mental functions.

- Mental accounting

- Adaptive bias — basing decisions on limited information and biasing them based on the costs of being wrong

- Attribute substitution — making a complex, difficult judgment by unconsciously replacing it with an easier judgment

- Attribution theory

- Cognitive dissonance, and related:

- Information-processing shortcuts (heuristics), including:

- Availability heuristic — estimating what is more likely by what is more available in memory, which is biased toward vivid, unusual, or emotionally charged examples

- Representativeness heuristic — judging probabilities based on resemblance

- Affect heuristic — basing a decision on an emotional reaction rather than a calculation of risks and benefits

- Emotional and moral motivations deriving, for example, from:

- Introspection illusion

- Misinterpretations or misuse of statistics; innumeracy.

- Social influence

- The brain's limited information processing capacity

- Noisy information processing (distortions during storage in and retrieval from memory). For example, a 2012 Psychological Bulletin article suggests that at least eight seemingly unrelated biases can be produced by the same information-theoretic generative mechanism. The article shows that noisy deviations in the memory-based information processes that convert objective evidence (observations) into subjective estimates (decisions) can produce regressive conservatism, the belief revision (Bayesian conservatism), illusory correlations, illusory superiority (better-than-average effect) and worse-than-average effect, subadditivity effect, exaggerated expectation, overconfidence, and the hard–easy effect.

Individual differences in cognitive biases

People do appear to have stable individual differences in their susceptibility to decision biases such as overconfidence, temporal discounting, and bias blind spot. That said, these stable levels of bias within individuals are possible to change. Participants in experiments who watched training videos and played debiasing games showed medium to large reductions both immediately and up to three months later in the extent to which they exhibited susceptibility to six cognitive biases: anchoring, bias blind spot, confirmation bias, fundamental attribution error, projection bias, and representativeness.

Individual differences in cognitive bias have also been linked to varying levels of cognitive abilities and functions. The Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) has been used to help understand the connection between cognitive biases and cognitive ability. There have been inconclusive results when using the Cognitive Reflection Test to understand ability. However, there does seem to be a correlation; those who gain a higher score on the Cognitive Reflection Test, have higher cognitive ability and rational-thinking skills. This in turn helps predict the performance on cognitive bias and heuristic tests. Those with higher CRT scores tend to be able to answer more correctly on different heuristic and cognitive bias tests and tasks.

Age is another individual difference that has an effect on one's ability to be susceptible to cognitive bias. Older individuals tend to be more susceptible to cognitive biases and have less cognitive flexibility. However, older individuals were able to decrease their susceptibility to cognitive biases throughout ongoing trials. These experiments had both young and older adults complete a framing task. Younger adults had more cognitive flexibility than older adults. Cognitive flexibility is linked to helping overcome pre-existing biases.

Criticism

Cognitive bias theory loses the sight of any distinction between reason and bias. If every bias can be seen as a reason, and every reason can be seen as a bias, then the distinction is lost.

Criticism against theories of cognitive biases is usually founded in the fact that both sides of a debate often claim the other's thoughts to be subject to human nature and the result of cognitive bias, while claiming their own point of view to be above the cognitive bias and the correct way to "overcome" the issue. This rift ties to a more fundamental issue that stems from a lack of consensus in the field, thereby creating arguments that can be non-falsifiably used to validate any contradicting viewpoint.

Gerd Gigerenzer is one of the main opponents to cognitive biases and heuristics. Gigerenzer believes that cognitive biases are not biases, but rules of thumb, or as he would put it "gut feelings" that can actually help us make accurate decisions in our lives. His view shines a much more positive light on cognitive biases than many other researchers. Many view cognitive biases and heuristics as irrational ways of making decisions and judgements.