Conservation in the United States can be traced back to the 19th century with the formation of the first National Park. Conservation generally refers to the act of consciously and efficiently using land and/or its natural resources. This can be in the form of setting aside tracts of land for protection from hunting or urban development, or it can take the form of using less resources such as metal, water, or coal. Usually, this process of conservation occurs through or after legislation on local or national levels is passed.

Conservation in the United States, as a movement, began with the American sportsmen who came to the realization that wanton waste of wildlife and their habitat had led to the extinction of some species, while other species were at risk. John Muir and the Sierra Club started the modern movement, history shows that the Boone and Crockett Club, formed by Theodore Roosevelt, spearheaded conservation in the United States.

While conservation and preservation both have similar definitions and broad categories, preservation in the natural and environmental scope refers to the action of keeping areas the way they are and trying to dissuade the use of its resources; conservation may employ similar methods but does not call for the diminishing of resource use but rather calls for a responsible way of going about it. A distinction between Sierra Club and Boone and Crockett Club is that Sierra Club was and is considered a preservationist organization whereas Boone and Crockett Club endorses conservation, simply defined as an "intelligent use of natural resources."

History

Philosophy of early American conservation movement

During the 19th century, some Americans developed a deep and abiding passion for nature. The early evolution of the conservation movement began through both public and private recognition of the relationship between man and nature often reflected in the great literary and artistic works of the 19th century. Artists, such as Albert Bierstadt, painted powerful landscapes of the American West during the mid 19th century, which were incredibly popular ages representative of the unique natural wonders of the American frontier. Likewise, in 1860, Frederic Edwin Church painted "Twilight in the Wilderness", which was an artistic masterpiece of the era that explored the growing importance of the American wilderness.

American writers also romanticized and focused upon nature as a subject matter. However, one of the most notable literary figures upon the early conservation movement proved to be Henry David Thoreau. Throughout his work, Walden, Thoreau detailed his experiences at the natural setting of Walden Pond and his deep appreciation for nature. In one instance, he described a deep grief for a tree that was cut down. Thoreau went on to bemoan the lack of reverence for the natural world: "I would that our farmers when they cut down a forest felt some of that awe which the old Romans did when they came to thin, or let in the light to, a consecrated grove". As he states in Walden, Thoreau "was interested in the preservation" of nature. In 1860, Henry David Thoreau delivered a speech to the Middlesex Agricultural Society in Massachusetts; the speech, entitled "The Succession of Forest Trees", explored forest ecology and encouraged the agricultural community to plant trees. This speech became one of Thoreau's "most influential ecological contributions to conservationist thought".

A basis for the philosophy curated by the prominent sportsmen, writers, anthropologists, and politicians came from observing Native Americans and how they interacted with the resources available to them. For example, George Bird Grinnell was an anthropologist who joined an expedition in 1870 which encountered different tribes such as the Pawnee for large, extended periods of time. He noted their use of every single part of an animal following a hunt and that they ceremoniously prepared for utilizing and taking any resource the land was able to provide them. These observations, fraught with condemning language toward the way European hunters and sportsmen treated wildlife and resources such as timber, were published in widely circulated journals and magazines at the time.

Early American Conservation Movement

The conservation of natural resources is the fundamental problem. Unless we solve that problem, it will avail us little to solve all others.

Theodore Roosevelt

America had its own conservation movement in the 19th century, most often characterized by George Perkins Marsh, author of Man and Nature. The expedition into northwest Wyoming in 1871 led by F. V. Hayden and accompanied by photographer William Henry Jackson provided the imagery needed to substantiate rumors about the grandeur of the Yellowstone region, and resulted in the creation of Yellowstone National Park, the world's first, in 1872. In 1887, Theodore Roosevelt, George Bird Grinnell and other prominent sportsmen of the day formed the first true North American conservation organization, the Boone and Crockett Club, with the purpose of addressing the looming conservation crises of the day. Travels by later U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt through the region around Yellowstone provided the impetus for the creation of the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve in 1891. The largest section of the reserve was later renamed Shoshone National Forest, and it is the oldest National Forest in the U.S. But it was not until 1898 when German forester Dr. Carl A. Schenck, on the Biltmore Estate, and Cornell University founded the first two forestry schools, both run by Germans. Bernard Fernow, founder of the forestry schools at Cornell and the University of Toronto, was originally from Prussia (Germany), and he honed his knowledge from Germans who pioneered forestry in India. He introduced Gifford Pinchot, the "father of American forestry", to Brandis and Ribbentrop in Europe. From these men, Pinchot learned the skills and legislative patterns he would later apply to America. Pinchot, in his memoir history Breaking New Ground, credited Brandis especially with helping to form America's conservation laws.

In 1891, Congress passed the Forest Reserve Act, which allowed the President of the United States to set aside forest lands on public domain. A decade after the Forest Reserve Act, presidents Harrison, Cleveland, and McKinley had transferred approximately 50,000,000 acres (200,000 km2) into the forest reserve system. However, President Theodore Roosevelt is credited with the institutionalization of the conservation movement in the United States.

John Muir

John Muir was one of the founding fathers of the preservation movement in the United States in the late 19th century. He believed that nature had intrinsic value and viewed nature as a sacred religious temple, which opposed the view of many utilitarian conservationists. One of Muir’s first endeavors was helping create Yosemite National Park. He first visited Yosemite in 1868 and went back annually until 1871. These visits ultimately led to his support to create Yosemite National Park nearly 20 years later in 1890.

Starting in the 1870s, when Muir first arrived, until 1930 there was a mass removal of Native American people from their homeland in Yosemite National Park. The majority of these people were from the Miwok tribe, which according to author Robert Enberg of the John Muir Newsletter, Muir characterized as “poor, lazy, and dirty” and according to author Jedediah Purdy as “four legged animal people”.

In 1901, Muir published the essay “Our National Parks” which was used to promote tourism to national parks. He assured future visitors and readers that most of the Native Americans were dead or civilized into useless innocence. This furthered the prominence of the racist ideologies Muir had to the Miwok tribe and other tribes he dealt with around the country.

After the creation of Yosemite National Park, Muir as well as the United States government pushed for the creation of Yellowstone and Glacier National Park. This led to the removal and killing of Native peoples. Early preservationists like Muir believed that these Native people were “‘primitives’ who were obstructing the progress of the nation's destiny” (544). These racist beliefs have been coined by historian Mark Spence as “the justifying myth”(544). which the government's and preservationists like Muir’s used to rationalize their political ideologies towards native people.

John Muir is remembered because of his respect for the non-human world and his unique view of nature. However, according to Jedediah Purdy, Muir’s views of Native people cannot be excused as “casual” for the time period he lived in. Overall, his impact on the early preservation movement has been monumental and still impacts us today.

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot was a key figure in the early conservation movement in the United States. After graduating from Yale in 1889 he pursued a career in forestry in which he was later appointed head of the Division of Forestry in 1898. Later he was appointed as the first chief of the United States Forest Service in 1905 under Theodore Roosevelt.

When appointed as the head of the U.S. Forest Service, Pinchot as well as President Roosevelt pushed what was known as “new conservationism.” This new wave of conservation led a more progressive agenda which forced the issue of conservation into the limelight. He believed “the fundamental principle of the whole conservation policy is that of use, to take every part of the land and its resources and put it to that use in which it will serve the most people '' (Pinchot 1913). Using this ideology he later pushed for the creation of national forests as well as one of Pinchot’s most controversial decisions in Hetch Hetchy Valley.

The damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley located in Yosemite National Park was proposed in 1913 by a conservationist group led by Pinchot and Roosevelt and was opposed by a group of preservationists led by John Muir. Pinchot’s view on conservation was more utilitarian, meaning he wanted to use nature's resources for the benefit of the public, while Muir believed that the Valley should not be touched as he viewed nature in a religious light. The O’Shaughnessy dam was ultimately built in 1923 and led to the drowning of the sacred indigenous land of the Miwok and Yokuts tribes.

Prior to the dam being built Native peoples had access to resources from the Tuolumne River. The river provided plant foods like seeds, berries, leaves, bulbs, and tubers. Year-around water was available for drinking, food preparation, and other practical uses. The area provided a plentiful food source for tribes that included birds, deer, and other mammals. These animals were also used for clothing and ornamentation. Plentiful fibers like grasses, sedges, and roots were used for baskets and other useful items. These resources also found their way into tools and weapons. The Native tribes used obsidian which became an important material resource used for arrow points, scrapers, and blades. Once the dam was put into place it destroyed the Miwok and Yokuts people's ways of life.

Pinchot’s impact in the early conservation movement in the United States is undeniable. However, the implementation of the dam was tragic for the Native people surrounding Hetch Hetchy. It was a complete landscape transformation and destroyed an entire ecosystem that the Native tribes once relied on.

Theodore Roosevelt

President Theodore Roosevelt believed the conservation movement was not about the preservation of nature simply for nature itself. After his experiences traveling as an enthusiastic, zealous hunter, Roosevelt became convinced of "the need for measures to protect the game species from further destruction and eventual extinction". President Roosevelt recognized the necessity of carefully managing America's natural resources. According to Roosevelt, "We are prone to speak of the resources of this country as inexhaustible; this is not so". Nonetheless, Roosevelt believed that conservation of America's natural resources was for the successful management and continued sustain yield harvesting of these resources in the future for the benefit and enjoyment of the American people. Roosevelt took several major steps to further his conservation goals. In 1902, Roosevelt signed the National Reclamation Act, which allowed for the management and settlement of a large tract of barren land. Then, in 1905, President Roosevelt helped to create the United States Forest Service and then appointed respected forester, Gifford Pinchot, as the first head of the agency. By the end of his presidency, Theodore Roosevelt, in partnership with Gifford Pinchot, had successfully increased the number of national parks and led to the forced removal of Native Americans from their homeland.

The legacy of his actions as president at the turn of the twentieth century include estimated 230 million acres of land as public lands, through his establishment of the United States Forest Service as well as dozens of national forests, national parks, and bird reserves, in addition to 4 game preserves. This legacy, though establishing what many consider the root of modern conservationism, remained within the hands of powerful men of white European heritage for years to come, often excluding the interests of Native Americans and other demographics within the United States.

Despite these advancements, the American conservation movement did have difficulties. In the early 1900s the conservation movement in America was split into two main groups: conservationists, like Pinchot and Roosevelt, who were utilitarian foresters and natural rights advocates who wanted to protect forests "for the greater good for the greatest length", and preservationists, like John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club. Important differences separated conservationists like Roosevelt and Pinchot from preservationists like Muir. Conservationists wanted regulated use of forest lands for both public activities and commercial endeavors, preservationists wanted forest to be preserved for natural beauty, scientific study, recreation, and believed only certain people should be able to visit these nature sites. The differences continue to the modern era, with sustainable harvest and multiple-use the major focus of the U.S. Forest Service and recreation emphasized by the National Park Service.

Although national parks can logistically fall under the category of preservation sites, certain marked National Conservation Area sites fall near or within proximity of national parks and share a common land history. The United States government began driving groups of Native American peoples out of popularly visited in Yellowstone around the late 1800s once they ironically deemed them a conflict to tourists. Battles between federal troops and the Nez Perce tribe soon ensued, and eventually the tribe was driven out of the area. Conservation history fails to incorporate details like this when talking about the beginnings and context of the movement.

Native American Removal and National Parks

Throughout the history of the United States conservation movement, Native people have been removed or set aside at the expense of creating “scenic playgrounds” across the country. The creation of several national parks like Yellowstone National Park in 1872, Yosemite National Park in 1890, and the creation of Glacier National Park in 1910, have all come at the expense of Native peoples. These parks were especially relevant because they held a native population. These parks became precedents for the exclusion of native people from their homeland and are all symbols of American wilderness movements.

The creation of Glacier National Park was possibly the most detrimental for indigenous tribes. Historian Mark David Spence explains how the Blackfeet people, whose reservation was located just east of Glacier National Park, were over time slowly removed and filtered out of their homeland through corrupt policy from the United States Department of the Interior. The tribe maintained an 1895 agreement with the United States that permitted them certain rights near and within the location of the park. In 1910 the Department of the Interior argued for their exclusion from Glacier National Park as they felt their presence in the glacier backcountry was “illegal.” Spence explains how “Blackfeet men and women who entertained tourists appeared to be living museum specimens who no longer used the Glacier wilderness- if, indeed, they ever had” (29).

The backcountry that the Blackfeet people were ultimately removed holds important religious sites, plants, and animals that the tribe has a deep connection to. The creation of the park also led to large increases in hunting in the area. The increase in hunting in the area from the late 19th century to the creation of the park led to the near extinction of the buffalo in the area. The Blackfeet people are deeply tied to hunting buffalo in the area as their meat would provide them food and their pelts provided them clothing. With the near extinction of buffalo in the area for sporting purposes,the Blackfeet people had to turn to other animals like elk and deer.

Modern American conservation movement

By the mid-twentieth century, conservation efforts continued to gain ground with the creation and implementation of federal legislation aimed at protecting wilderness, natural resources, and wildlife. This trend on the part of the federal government towards a more protection minded approach to the environment began with the passage of the Federal Water Pollution Act in 1948 and the Air Pollution Control Act in 1955. While neither of these regulations themselves served to impose tight restrictions on either water or air pollution, they lay the groundwork for what would later become the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act, as well as serving to demonstrate the recognition on the part of the federal government of the need to codify regulations geared towards environmental protection.

Notable Events

1962: Silent Spring

The 1962 publication of Rachel Carson's best seller book Silent Spring represented a major watershed moment in American conservation. In exposing the individual dangers presented to both people and nature through the use of chemical pesticides, Carson inspired an environmental revolution, helping to root the modern conservation movement in a scientific foundation. It would take another decade, however, before the use of DDT was banned in the United States.

1960s: Orca Conservation and Its Effect on Indigenous Kinship Relationships

Native American Nations have fought throughout history to practice Tribally unique kinship relationships with the nonhuman world.. The push for progressive conservation in the United States in the late 19th century and early 20th century destroyed many kinship relationships Native tribes had with the nonhuman world.

U.S. conservation practices harming Native kinship relations continued into the 1960s. Demand for ocean exhibits was at an all-time high in the United States. This pushed the initiative for the capturing of orcas (killer whales) in the Salish Sea located in the northwest United States. Hundreds of orcas were captured and displaced from their families as well as many being killed in the process. The primary goals of these exhibits were supposed to be for public education and conservation efforts. However, These whales have been used for economic benefit for sea parks across the world. Since 1961, during the push for public orca conservation education “at least 179 orcas have died in captivity, not including 30 miscarried or still-born calves.”

The Lummi Nation native to the Salish Sea have deep kinship ties to the killer whale, and in recent years have been fighting to release these animals from captivity. Lummi tribal matriarch Raynell Morris explains that the Lummi have “lived with killer whales since time immemorial and call them qwe’lhol’mechen, the people beneath the waves because we see them as people whose cetacean regalia allows them to live underwater.” The Lummi believe that healing the orca population or “family” will help heal their Lummi and human selves. In recent years Morris and members of the Lummi nation launched an initiative to have a whale from the Miami Aquarium released named Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, who had spent nearly 50 years in captivity. In 2023, Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut was set to be released but died of kidney failure just before she was released.

According to environmental scholars, U.S. environmental agencies like the NOAA are “treating the whales as educational, economic, and environmental possessions while degrading the relationship of the Lummi to the whales as relatives and attacking Lummi sovereignty.” For generations, Lummi rituals have shown to be very effective when it comes to sustaining and conserving salmon and orca populations, but Native people and their traditions are being pushed aside as they have been throughout the history of conservation in the United States.

The Wilderness Act of 1964

On 3 September 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act of 1964 into law. This milestone was achieved by the efforts of environmental conservationists dedicated to the protection of some of the wildest lands in the United States. Chief among these were Howard Zahniser and Olaus Murie and Mardy Murie, and Celia Hunter, who dedicated much of their lives and their work to the protection and conservation of wild lands. By 1950 both Zanhiser and Olaus Murie were working for the Wilderness Society, Zahinser as Executive Secretary in Washington DC, and Olaus as president from his ranch in Moose, WY (now home to the Murie Center). From their positions at Wilderness Society, both men continued to work to organize and build broad-based support for the creation and protection of wilderness areas within the United States. Zahniser felt strongly that Congress ought to designate wilderness areas, as opposed to leaving it up to Agency discretion, and, in 1955, began working to convince members of Congress to support a bill that would establish a national wilderness preservation system. Meanwhile, in 1956, Olaus and Mardy Murie embarked upon an expedition to the upper Sheenjek River on the south slope of the Brooks Range in Alaska, which would galvanize them to campaign for the protection of the area as a wildlife refuge. Celia Hunter, with Ginny Wood, founded the Alaska Conservation Society, the first statewide environmental organization, in 1960. Serving on the board, she worked tirelessly to get legislation passed to protect Alaskan wilderness. Celia was also the first female president of the Wilderness Society. The result of these efforts was the protection of 8 million acres as the Arctic National Wildlife Range, renamed the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge when it was expanded to 19 million acres in 1980. Moreover, the mission underlying the protection of ANWR, namely the preservation of an entire ecological system, became the underlying motivation for the preservation of other large tracts of wild lands.

While neither Zahniser nor Olaus Murie would live to see the Wilderness Act signed by President Johnson, it is unlikely that, without their tireless efforts, the preservation movement would have been able to achieve so huge a victory. On 3 September 1964, Mardy Murie stood proudly next to President Johnson in the Rose Garden at the White House and bore witness to the making of history, and the achievement of the very thing for which Zahniser and Olaus had campaigned so ardently.

Clinton Administration 1993-2001

Though liberal Democrats gave environmentalism a higher priority than the economy-focused President Bill Clinton did, the Clinton administration responded to public demand for environmental protection. Clinton created 17 national monuments by executive order, prohibiting commercial activities such as logging, mining, and drilling for oil or gas. Clinton also imposed a permanent freeze on drilling in maritime sanctuaries. Other presidential and departmental orders protected various wetlands and coastal resources and extended the existing moratorium on new oil leases off the coast line through 2013. After the Republican victory in the 1994 elections, Clinton vetoed a series of budget bills that contained amendments designed to scale back environmental restrictions. Clinton boasted that his administration "adopted the strongest air-quality protections ever, improved the safety of our drinking water and food, cleaned up about three times as many toxic waste sites as the two previous administrations combined, [and] helped to promote a new generation of fuel-efficient vehicles and vehicles that run on alternative fuels".

Vice President Gore was keenly concerned with global climate change, and Clinton created the President's Council on Sustainable Development. In November 1998, Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol, an international agreement in which developed countries committed to reducing carbon emissions. However, the Senate refused to ratify it since the agreement did not apply to the rapidly growing emissions of developing countries such as China, India, and Indonesia.

The key person on environmental issues was Bruce Babbitt, the head of the League of Conservation Voters, who served for all eight years as the United States Secretary of the Interior. According to John D. Leshy:

- His most remembered legacies will likely be his advocacy of environmental restoration, his efforts to safeguard and build support for the ESA (Endangered Species Act of 1973) and the biodiversity the that it helps protect., And the public land conservation measures that flowered on his watch.

The Interior Department worked to protect scenic and historic areas of America's federal public lands. In 2000 Babbitt created the National Landscape Conservation System, a collection of 15 U.S. National Monuments and 14 National Conservation Areas to be managed by the Bureau of Land Management in such a way as to keep them "healthy, open, and wild."

A major issue involved low fees charged ranchers who grazed cattle on public lands. The "animal unit month" (AUM) fee was only $1.35 and was far below the 1983 market value. The argument was that the federal government in effect was subsidizing ranchers, with a few major corporations controlling millions of acres of grazing land. Babbitt and Oklahoma Congressman Mike Synar tried to rally environmentalists and raise fees, but senators from Western states successfully blocked their proposals.

Twenty-First Century

Ultimately, the modern conservation movement in the United States continues to strive for the delicate balance between the successful management of society's industrial progress while still preserving the integrity of the natural environment that sustains humanity. In a large part, today's conservation movement in the United States is a joint effort of individuals, grassroots organizations, nongovernmental organizations, learning institutions, and various government agencies, such as the United States Forest Service.

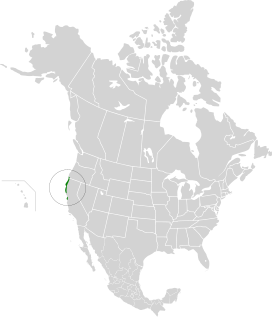

For the modern era, the U.S. Forest Service has noted three important aspects of the conservation movement: the climate change, water issues, and the education of the public on conservation of the natural environment, especially among children. In regards to climate change, the U.S. Forest Service has undertaken a twenty-year research project to develop ways to counteract issues surrounding climate change. However, some small steps have been taken regarding climate change. As rising greenhouse gases contribute to global warming, reforestation projects are seeking to counteract rising carbon emissions. In Oregon, the Department of Forestry has developed a small reforestation program in which landowners can lease their land for one hundred years to grow trees. In turn, these trees offset carbon emissions from power companies. Moreover, reforestation projects have other benefits: reforested areas serve as a natural filter of agricultural fertilizers even as new wildlife habitats are created. Reforested land can also contribute to the local economy as rural landowners also distribute hunting leases during the years between harvests.

In essence, projects, such as reforestation, create a viable market of eco-friendly services mutually beneficial to landowners, businesses and society, and most importantly, the environment. Nonetheless, such creative plans will be necessary in the near future as the United States struggles to maintain a positive balance between society and the finite natural resources of the nation. Ultimately, through dedicated research, eco-friendly practices of land management, and efforts to educate the public regarding the necessity of conservation, those individuals dedicated to American conservation seek to preserve the nation's natural resources.

Twenty-First Century resource protection

The increased consumption of many natural resources has sparked the need for protection. Many of these resources were barely touched less than half a century ago but have been drained in several situations. One of these resources, water, is key to survival of almost all life but is being used quicker than it is replenished in many states within the United States. This has created the need for greater conservation which has been met by new techniques and technologies for both reducing the amount of water being used and increasing how efficiently it is being used. Some of these methods are as simple as replacing the fixtures in government buildings and offering rebates to citizens, but are as complex as growing genetically engineered food crops so that farmers can consume less water for use on them.

Another key resource that has been met with new legislation is the land that is used to grow the crops for farms. One fairly new United States government policy, the Farmland Protection Policy Act, is designed in order to protect this resource from being over consumed by the government. It does this by ensuring that any entity, both federal and non-federal, that uses government assistance such as acquiring or disposing of land, providing financing or loans, managing property, providing technical assistance, cannot convert agricultural land into land that is permanently used for other purposes if it can be avoided.

If the overuse of these resources is not mitigated, the eventual result would be the loss of another key resource for survival. That is, if either land for agriculture or water for the land and the people who inhabit it becomes insufficient, the population in the United States would begin to run out of food. Not only would cash crops of plants become insufficient to supply people, it would also become insufficient to feed the livestock and animals that also depend on plants that are grown on agricultural land. Because of this, the need for conservation is greater than ever, especially when current efforts have only been able to slow the gradual depletion of these two key resources while increased populations create the need for higher consumption.

Ecotourism

The goal of ecotourism is to attract appreciation and attention to specific sites, which may include protected land for conservation, while minimizing the impact that tourism has on the land. It is a form of conservation because the area may be protected while tourists or businesses are also using the land for lodging or other types of accommodations that utilize resources in any way. This movement has gained international traction and recognition. The United Nations declared 2002 the International Year of Ecotourism. Ecotourism seeks to balance an interest and appreciation of protected lands with a commitment to preserving them. A study conducted by the University of Georgia reported that environmentalists should team up with ecotourists in order to have the best chance to preserve fragile ecosystems and lands. Tourism provides economic incentives to conserve lands, for if protected lands are seen as revenue-generating tourist destinations, there is monetary reason to ensure their conservation. Also, rather than simply relying on environmental messaging, ecotourism allows conservationists to pursue a leisurely and economic message.

Current Conservation Developments & Issues

Social Issues and Threats to Access

At a 2014 event held at UCLA centered upon environmental figures like John Muir, a few historians and writers noted that the movements for conservation and preservation of the environment maintained a foundation in "economic privilege and abundant leisure time of the upper class." Jon Christensen, a historian of UCLA's Institute of Environment and Sustainability, notes among the other critics at the event that writings and actions from conservationists at the turn of the twentieth century have created a legacy for the movement as one of an older white demographic.

General concern among the current conservation movement deals with the accessibility of conserved/protected areas as well as the movement itself to communities of color especially. Richard White, a historian at Stanford University, makes the case that viewpoints of early conservationists came from an Anglo-Saxon, biblical point of view and that this is reflected in the current demographics of visitors to national parks and protected areas. At the same time, recent polls suggest that the Latino community in California tends to possess more environmental attitudes when it comes to voting than perceived by the general public. A highly cited historian of Southern California, D. J. Waldie, posits that conservation for the purpose of public enjoyment is usually geared for places inaccessible to minority demographics, such as skiing or backpacking in the Sierra Nevadas. Instead, he puts forth that the conservation areas of importance for these communities are local bodies of water or small mountain ranges, urban parks, and even their own backyards.

Indigenous Conservation

Citizen Potawatomi environmental scholar Kyle Powys White believes that just futures for indigenous people through conservation must be tailored to the specific needs and values of each indigenous community. He believes that “while surface similarities are present, it is perhaps more accurate to say that indigenous conservationists and restorationists tend to focus on sustaining particular plants and animals whose lives are entangled locally—and often over many generations—in ecological, cultural, and economic relationships with human societies and other nonhuman species” (2). Providing Native people the ability to use their traditional methods to conserve and restore of native species, can be one of the first steps taken in order to give just futures for indigenous people.

Tulalip Tribal professor Stephanie Fyrberg believes that in order to bring just futures to indigenous people their stories must be told. Fryberg says “throughout history, Natives in this country have been pushed aside and our experiences have been erased. We were put on reservations that were often extremely remote and we were characterized in entertainment as either noble savages or as people broken by centuries of colonization. In many respects, these actions and stories erased, misrepresented, and dehumanized us.” Hearing indigenous stories can help bring just futures for Native people and can bring ecological health futures to not just indigenous people but all people using indigenous conservation methods.

Events

Past Events

- Extinction of the Passenger pigeon

- Wholesale hunting of American Bison

Current Events

Enforcement

Game wardens or conservation officers are employed to protect wildlife and natural areas.

- Florida Department of Environmental Protection

- Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries - Enforcement Division

- Maryland Department of Natural Resources Police

- Maine Warden Service

- Michigan Conservation Officers and Michigan Department of Natural Resources (Wildlife Division)

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Police

- Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries

Projects

Political

On January 20, 2017, a bill was introduced to congress that aimed to roll back regulations on oil and gas drilling in National Parks. The bill would nullify the "General Provisions and Non-Federal Oil and Gas Rights" rule passed in November 2016, and this would remove protections to National Park lands and resources.

On February 28, 2017, Donald Trump signed an executive order to review the Clean Water Rule, a bill he and Scott Pruitt have pledged to eliminate since he took office. The Clean Water rule was enacted in 2015 and extended federal protection to millions of acres of lakes, rivers, and wetlands.

On March 16, 2017, Donald Trump released his preliminary budget proposal for 2018 discretionary spending. These budget proposals featured cuts to both the EPA and the Department of Interior. The 12% decrease for the Department of Interior is removing spending from land acquisition costs associated with the preservation and expansion of National Parks. The budget also completely defunded National Heritage Areas. Funding to National Heritage Areas is used in part to support tribal protection officers and provides grants to underrepresented communities, ones who have already been putting conservation in practice. The proposed budget would cut the staff of the Environmental Protection Agency by 3,200 and reduce their budget by $2.6 billion annually.

Trump's promise to eliminate 2 federal regulations for every new regulation proposed may impact lands set aside for conservation. The repeal of old regulations will put currently conserved land at risk: future perceived threats to conserved lands and resources might not be able to be stopped since the erasure of regulation that sought to combat past threats to conserved lands may be eliminated.

Ryan Zinke, Trump's appointed Secretary of the Interior, moved to reverse federal regulation that prohibits hunters from using lead ammunition in National Parks.

According to a report from the Center for American Progress, the administration of Joe Biden reached a record in conservation. In 3 years of ruling it conserved or in the process of conserving more than 24 millions acres of public land and in 2023 alone more than 12.5 million acres of public land became protected area. It is doing it together with the indigenous people as 200 agreements of co-stewardship with them were signed in 2023 alone.

Protected areas

Key figures

Some of the more notable American conservationists include:

- George Perkins Marsh

- John Wesley Powell

- John Muir, naturalist and nature writer; founder of the Sierra Club

- Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States and founder of the Boone and Crockett Club

- Aldo Leopold, influential in the development of modern environmental ethics and in the movement for wilderness preservation

- David Brower, first Exec. Dir. of the Sierra Club; founder of Friends of the Earth, the League of Conservation Voters and Earth Island Institute

- Ansel Adams, known for his black-and-white photographs of Yosemite; served on the Sierra Club's board of directors

- Howard Zahniser, Exec. Dir. of the Wilderness Society and principal author of the Wilderness Act of 1964

- Rachel Carson

- Margaret Murie

- Olaus Murie

- Celia Hunter