Iceland (Icelandic: Ísland, pronounced [ˈistlant] ) is a Nordic island country between the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is linked culturally and politically with Europe and is the region's most sparsely populated country. Its capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which is home to about 36% of the country's roughly 380,000 residents. The official language of the country is Icelandic.

Located on a rift between tectonic plates, Iceland's geologic activity includes geysers and frequent volcanic eruptions. The interior consists of a volcanic plateau characterised by sand and lava fields, mountains, and glaciers, and many glacial rivers flow to the sea through the lowlands. Iceland is warmed by the Gulf Stream and has a temperate climate, despite a latitude just south of the Arctic Circle. Its high latitude and marine influence keep summers chilly, and most of its islands have a polar climate.

According to the ancient manuscript Landnámabók, the settlement of Iceland began in 874 AD when the Norwegian chieftain Ingólfr Arnarson became the first permanent settler on the island. In the following centuries, Norwegians, and to a lesser extent other Scandinavians, immigrated to Iceland, bringing with them thralls (i.e., slaves or serfs) of Gaelic origin.

The island was governed as an independent commonwealth under the native parliament, the Althing, one of the world's oldest functioning legislative assemblies. Following a period of civil strife, Iceland acceded to Norwegian rule in the 13th century. In 1397, Iceland followed Norway's integration into the Kalmar Union along with the kingdoms of Denmark and Sweden, coming under de facto Danish rule following its dissolution in 1523. The Danish kingdom introduced Lutheranism by force in 1550, and Iceland was formally ceded to Denmark in 1814 by the Treaty of Kiel.

Influenced by ideals of nationalism after the French Revolution, Iceland's struggle for independence took form and culminated in the Danish–Icelandic Act of Union in 1918, with the establishment of the Kingdom of Iceland, sharing through a personal union the incumbent monarch of Denmark. During the occupation of Denmark in World War II, Iceland voted overwhelmingly to become a republic in 1944, thus ending the remaining formal ties with Denmark. Although the Althing was suspended from 1799 to 1845, the island republic nevertheless holds a claim to sustaining one of the longest-running parliaments in the world.

Until the 20th century, Iceland relied largely on subsistence fishing and agriculture. Industrialization of the fisheries and Marshall Plan aid following World War II brought prosperity, and Iceland became one of the wealthiest and most developed nations in the world. It became a part of the European Economic Area in 1994; this further diversified the economy into sectors such as finance, biotechnology, and manufacturing.

Iceland has a market economy with relatively low taxes, compared to other OECD countries, as well as the highest trade union membership in the world. It maintains a Nordic social welfare system that provides universal health care and tertiary education for its citizens. Iceland ranks highly in international comparisons of national performance, such as quality of life, education, protection of civil liberties, government transparency, and economic freedom. Iceland has the smallest population of any NATO member and is the only one with no standing army, possessing only a lightly armed coast guard.

Etymology

The Sagas of Icelanders say that a Norwegian named Naddodd (or Naddador) was the first Norseman to reach Iceland; in the ninth century, he named it Snæland or "snow land" because it was snowing. Following Naddodd, the Swede Garðar Svavarsson arrived, and so the island was then called Garðarshólmur, which means "Garðar's Isle".

Then came a Viking named Flóki Vilgerðarson; his daughter drowned en route, then his livestock starved to death. The sagas say that the rather despondent Flóki climbed a mountain and saw a fjord (Arnarfjörður) full of icebergs, which led him to give the island its new and present name. The notion that Iceland's Viking settlers chose that name to discourage the settlement of their verdant isle is a myth.

History

874–1262: settlement and Commonwealth

According to both Landnámabók and Íslendingabók, monks known as the Papar lived in Iceland before Scandinavian settlers arrived, possibly members of a Hiberno-Scottish mission. Recent archaeological excavations have revealed the ruins of a cabin in Hafnir on the Reykjanes peninsula. Carbon dating indicates that it was abandoned sometime between 770 and 880. In 2016, archaeologists uncovered a longhouse in Stöðvarfjörður that has been dated to as early as 800.

Swedish Viking explorer Garðar Svavarsson was the first to circumnavigate Iceland in 870 and establish that it was an island. He stayed during the winter and built a house in Húsavík. Garðar departed the following summer, but one of his men, Náttfari, decided to stay behind with two slaves. Náttfari settled in what is now known as Náttfaravík, and he and his slaves became the first permanent residents of Iceland to be documented.

The Norwegian-Norse chieftain Ingólfr Arnarson built his homestead in present-day Reykjavík in 874. Ingólfr was followed by many other emigrant settlers, largely Scandinavians and their thralls, many of whom were Irish or Scottish. By 930, most arable land on the island had been claimed; the Althing, a legislative and judicial assembly was initiated to regulate the Icelandic Commonwealth. The lack of arable land also served as an impetus to the settlement of Greenland starting in 986. The period of these early settlements coincided with the Medieval Warm Period, when temperatures were similar to those of the early 20th century. At this time about 25% of Iceland was covered with forest, compared to 1% in the present day. Christianity was adopted by consensus around 999–1000, although Norse paganism persisted among segments of the population for some years afterward.

The Middle Ages

The Icelandic Commonwealth lasted until the 13th century when the political system devised by the original settlers proved unable to cope with the increasing power of Icelandic chieftains. The internal struggles and civil strife of the Age of the Sturlungs led to the signing of the Old Covenant in 1262, which ended the Commonwealth and brought Iceland under the Norwegian crown. Possession of Iceland passed from the Kingdom of Norway (872–1397) to the Kalmar Union in 1415, when the kingdoms of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden were united. After the break-up of the union in 1523, it remained a Norwegian dependency, as a part of Denmark–Norway.

Infertile soil, volcanic eruptions, deforestation, and an unforgiving climate made for harsh life in a society where subsistence depended almost entirely on agriculture. The Black Death swept Iceland twice, first in 1402–1404 and again in 1494–1495. The former outbreak killed 50% to 60% of the population, and the latter 30% to 50%.

Reformation and the Early Modern period

Around the middle of the 16th century, as part of the Protestant Reformation, King Christian III of Denmark began to impose Lutheranism on all his subjects. Jón Arason, the last Catholic bishop of Hólar, was beheaded in 1550 along with two of his sons. The country subsequently became officially Lutheran, and Lutheranism has since remained the dominant religion.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Denmark imposed harsh trade restrictions on Iceland. Natural disasters, including volcanic eruptions and disease, contributed to a decreasing population. In the summer of 1627, Barbary Pirates committed the events known locally as the Turkish Abductions, in which hundreds of residents were taken into slavery in North Africa and dozens killed; this was the only invasion in Icelandic history to have casualties. The 1707–08 Iceland smallpox epidemic is estimated to have killed a quarter to a third of the population. In 1783 the Laki volcano erupted, with devastating effects. In the years following the eruption, known as the Mist Hardships (Icelandic: Móðuharðindin), over half of all livestock in the country died. Around a quarter of the population starved to death in the ensuing famine.

1814–1918: independence movement

In 1814, following the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark-Norway was broken up into two separate kingdoms via the Treaty of Kiel, but Iceland remained a Danish dependency. Throughout the 19th century, the country's climate continued to grow colder, resulting in mass emigration to the New World, particularly to the region of Gimli, Manitoba in Canada, which was sometimes referred to as New Iceland. About 15,000 people emigrated, out of a total population of 70,000.

A national consciousness arose in the first half of the 19th century, inspired by romantic and nationalist ideas from mainland Europe. An Icelandic independence movement took shape in the 1850s under the leadership of Jón Sigurðsson, based on the burgeoning Icelandic nationalism inspired by the Fjölnismenn and other Danish-educated Icelandic intellectuals. In 1874, Denmark granted Iceland a constitution and limited home rule. This was expanded in 1904, and Hannes Hafstein served as the first Minister for Iceland in the Danish cabinet.

1918–1944: independence and the Kingdom of Iceland

The Danish–Icelandic Act of Union, an agreement with Denmark signed on 1 December 1918 and valid for 25 years, recognised Iceland as a fully sovereign and independent state in a personal union with Denmark. The Government of Iceland established an embassy in Copenhagen and requested that Denmark carry out on its behalf certain defence and foreign affairs matters, subject to consultation with the Althing. Danish embassies around the world displayed two coats of arms and two flags: those of the Kingdom of Denmark and those of the Kingdom of Iceland. Iceland's legal position became comparable to those of countries belonging to the Commonwealth of Nations, such as Canada, whose sovereign is King Charles III.

During World War II, Iceland joined Denmark in asserting neutrality. After the German occupation of Denmark on 9 April 1940, the Althing replaced the King with a regent and declared that the Icelandic government would take control of its own defence and foreign affairs. A month later, British armed forces conducted Operation Fork, the invasion and occupation of the country, violating Icelandic neutrality. In 1941, the Government of Iceland, friendly to Britain, invited the then-neutral United States to take over its defence so that Britain could use its troops elsewhere.

1944–present: Republic of Iceland

On 31 December 1943, the Danish–Icelandic Act of Union expired after 25 years. Beginning on 20 May 1944, Icelanders voted in a four-day plebiscite on whether to terminate the personal union with Denmark, abolish the monarchy, and establish a republic. The vote was 97% to end the union, and 95% in favour of the new republican constitution. Iceland formally became a republic on 17 June 1944, with Sveinn Björnsson as its first president.

In 1946, the US Defence Force Allied left Iceland. The nation formally became a member of NATO on 30 March 1949, amid domestic controversy and riots. On 5 May 1951, a defence agreement was signed with the United States. American troops returned to Iceland as the Iceland Defence Force and remained throughout the Cold War. The US withdrew the last of its forces on 30 September 2006.

Iceland prospered during the Second World War. The immediate post-war period was followed by substantial economic growth, driven by the industrialisation of the fishing industry and the US Marshall Plan programme, through which Icelanders received the most aid per capita of any European country (at US$209, with the war-ravaged Netherlands a distant second at US$109).

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir assumed Iceland's presidency on 1 August 1980, making her the first elected female head of state in the world.

The 1970s were marked by the Cod Wars—several disputes with the United Kingdom over Iceland's extension of its fishing limits to 200 nmi (370 km) offshore. Iceland hosted a summit in Reykjavík in 1986 between United States President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev, during which they took significant steps towards nuclear disarmament. A few years later, Iceland became the first country to recognise the independence of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania as they broke away from the USSR. Throughout the 1990s, the country expanded its international role and developed a foreign policy orientated towards humanitarian and peacekeeping causes. To that end, Iceland provided aid and expertise to various NATO-led interventions in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Iraq.

Iceland joined the European Economic Area in 1994, after which the economy was greatly diversified and liberalised. International economic relations increased further after 2001 when Iceland's newly deregulated banks began to raise great amounts of external debt, contributing to a 32 percent increase in Iceland's gross national income between 2002 and 2007.

Economic boom and crisis

In 2003–2007, following the privatisation of the banking sector under the government of Davíð Oddsson, Iceland moved towards having an economy based on international investment banking and financial services. It was quickly becoming one of the most prosperous countries in the world, but was hit hard by a major financial crisis. The crisis resulted in the greatest migration from Iceland since 1887, with a net emigration of 5,000 people in 2009.

Since 2012

Iceland's economy stabilised under the government of Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir and grew by 1.6% in 2012. The centre-right Independence Party was returned to power in coalition with the Progressive Party in the 2013 election. In the following years, Iceland saw a surge in tourism as the country became a popular holiday destination. In 2016, Prime Minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson resigned after being implicated in the Panama Papers scandal. Early elections in 2016 resulted in a right-wing coalition government of the Independence Party, the Reform Party and Bright Future. This government fell when Bright Future quit the coalition due to a scandal involving then-Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson's father's letter of support for a convicted child sex offender. Snap elections in October 2017 brought to power a new coalition consisting of the Independence Party, the Progressive Party, and the Left-Green Movement, headed by Katrín Jakobsdóttir.

After the 2021 parliamentary election, the new government was, just like the previous government, a tri-party coalition of the Independence Party, the Progressive Party, and the Left-Green Movement, headed by Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir. In April 2024, Bjarni Benediktsson of the Independence party succeeded Katrín Jakobsdóttir as prime minister.

Geography

Iceland is at the juncture of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. The main island is entirely south of the Arctic Circle, which passes through the small Icelandic island of Grímsey off the main island's northern coast. The country lies between latitudes 63 and 68°N, and longitudes 25 and 13°W.

Iceland is closer to continental Europe than to mainland North America, although it is closest to Greenland (290 kilometres; 155 nautical miles), an island of North America. Iceland is generally included in Europe for geographical, historical, political, cultural, linguistic and practical reasons. Geologically, the island includes parts of both continental plates. The closest bodies of land in Europe are the Faroe Islands (420 km; 225 nmi); Jan Mayen Island (570 km; 310 nmi); Shetland and the Outer Hebrides, both about 740 km (400 nmi); and the Scottish mainland and Orkney, both about 750 km (405 nmi). The nearest part of Continental Europe is mainland Norway, about 970 km (525 nmi) away, while mainland North America is 2,070 km (1,120 nmi) away, at the northern tip of Labrador.

Iceland is the world's 18th-largest island, and Europe's second-largest island after Great Britain and before Ireland. The main island covers 101,826 km2 (39,315 sq mi), but the entire country is 103,000 km2 (40,000 sq mi) in size, of which 62.7% is tundra. Iceland contains about 30 minor islands, including the lightly populated Grímsey and the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago. Lakes and glaciers cover 14.3% of its surface; only 23% is vegetated. The largest lakes are Þórisvatn reservoir: 83–88 km2 (32–34 sq mi) and Þingvallavatn: 82 km2 (32 sq mi); other important lakes include Lagarfljót and Mývatn. Jökulsárlón is the deepest lake, at 248 m (814 ft).

Geologically, Iceland is part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a ridge along which the oceanic crust spreads and forms new crust. This part of the mid-ocean ridge is located above a mantle plume, causing Iceland to be subaerial (above the surface of the sea). The ridge marks the boundary between the Eurasian and North American Plates, and Iceland was created by rifting and accretion through volcanism along the ridge.

Many fjords punctuate Iceland's 4,970-km-long (3,088-mi) coastline, which is also where most settlements are situated. The island's interior, the Highlands of Iceland, is a cold and uninhabitable combination of sand, mountains, and lava fields. The major towns are the capital city of Reykjavík, along with its outlying towns of Kópavogur, Hafnarfjörður, and Garðabær, nearby Reykjanesbær where the international airport is located, and the town of Akureyri in northern Iceland. The island of Grímsey on the Arctic Circle contains the northernmost habitation of Iceland, whereas Kolbeinsey contains the northernmost point of Iceland. Iceland has three national parks: Vatnajökull National Park, Snæfellsjökull National Park, and Þingvellir National Park. The country is considered a "strong performer" in environmental protection, having been ranked 13th in Yale University's Environmental Performance Index of 2012.

Geology

A geologically young land at 16 to 18 million years old, Iceland is the surface expression of the Iceland Plateau, a large igneous province forming as a result of volcanism from the Iceland hotspot and along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the latter of which runs right through it. This means that the island is highly geologically active with many volcanoes including Hekla, Eldgjá, Herðubreið, and Eldfell. The volcanic eruption of Laki in 1783–1784 caused a famine that killed nearly a quarter of the island's population. In addition, the eruption caused dust clouds and haze to appear over most of Europe and parts of Asia and Africa for several months afterwards, and affected climates in other areas.

Iceland has many geysers, including Geysir, from which the English word is derived, and the famous Strokkur, which erupts every 8–10 minutes. After a phase of inactivity, Geysir started erupting again after a series of earthquakes in 2000. Geysir has since grown quieter and does not erupt often.

With the widespread availability of geothermal power and the harnessing of many rivers and waterfalls for hydroelectricity, most residents have access to inexpensive hot water, heating, and electricity. The island is composed primarily of basalt, a low-silica lava associated with effusive volcanism as has occurred also in Hawaii. Iceland, however, has a variety of volcanic types (composite and fissure), many producing more evolved lavas such as rhyolite and andesite. Iceland has hundreds of volcanoes with about 30 active volcanic systems.

Surtsey, one of the youngest islands in the world, is part of Iceland. Named after Surtr, it rose above the ocean in a series of volcanic eruptions between 8 November 1963 and 5 June 1968. Only scientists researching the growth of new life are allowed to visit the island.

On 21 March 2010, a volcano in Eyjafjallajökull in the south of Iceland erupted for the first time since 1821, forcing 600 people to flee their homes. Additional eruptions on 14 April forced hundreds of people to abandon their homes. The resultant cloud of volcanic ash brought major disruption to air travel across Europe.

Another large eruption occurred on 21 May 2011. This time it was the Grímsvötn volcano, located under the thick ice of Europe's largest glacier, Vatnajökull. Grímsvötn is one of Iceland's most active volcanoes, and this eruption was much more powerful than the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull activity, with ash and lava hurled 20 km (12 mi) into the atmosphere, creating a large cloud.

A great deal of volcanic activity occurred in the Reykjanes Peninsula in 2020 and into 2021, after nearly 800 years of inactivity. After the eruption of the Fagradalsfjall volcano on 19 March 2021, National Geographic's experts predicted that this "may mark the start of decades of volcanic activity." The eruption was small, leading to a prediction that this volcano was unlikely to threaten "any population centers".

The highest elevation for Iceland is listed as 2,110 m (6,920 ft) at Hvannadalshnúkur (64°00′N 16°39′W).

2023 and 2024 eruptions

On December 18, 2023, an eruption began at the Sundhnúkur crater row in the Eldvörp–Svartsengi volcanic system on Iceland's Reykjanes peninsula about 4 km northeast of the fishing community of Grindavik, which had been evacuated in November after strong seismic activity had damaged roads, homes and other structures and raised fears of an imminent eruption. The November earthquakes also prompted the closure of the Blue Lagoon geothermal spa—one of Iceland's biggest tourist attractions. The eruption was a 3.5 km linear fissure vent event in an area where there had been recent concentrated crustal uplift, with lava fountains reaching as high as 100 meters. Unlike the 2010 eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull, this event wasn't expected to cause significant disruption due to the volcano's limited ash cloud generation. The eruption was short-lived, with activity rapidly decreasing in strength and stopping on December 21.

A new eruption began on January 14, 2024, shortly after authorities evacuated Grindavik due to a swarm of small earthquakes. Hours later, a second fissure opened near the edge of town, with lava creeping toward homes. Defensive walls that had been built north of Grindavik were breached. Lava flow from the initial fissure cut the main road to Grindavik while lava from the second fissure destroyed three homes. The eruption stopped after two days.

On February 8, a third eruption started in the same area as the December eruption.

On March 16, a fourth eruption began between Mt. Hagafell and Mt. Stóra-Skógfell. Initially, it was a 3 km fissure eruption, but it gradually evolved to lava discharging from several vents and eventually to a single vent that had developed into a spatter cone. Activity continued into April with varying levels of intensity and lava flow. Rather than extend into new areas, the lava flowed over previous flows from this same eruption, forming a shield around the cone.

Climate

The climate of Iceland's coast is subarctic. The warm North Atlantic Current ensures generally higher annual temperatures than in most places of similar latitude in the world. Regions in the world with similar climates include the Aleutian Islands, the Alaska Peninsula, and Tierra del Fuego, although these regions are closer to the equator. Despite its proximity to the Arctic, the island's coasts remain ice-free through the winter. Ice incursions are rare, with the last having occurred on the north coast in 1969.

The climate varies between different parts of the island. Generally speaking, the south coast is warmer, wetter, and windier than the north. The Central Highlands are the coldest part of the country. Low-lying inland areas in the north are the aridest. Snowfall in winter is more common in the north than in the south.

The highest air temperature recorded was 30.5 °C (86.9 °F) on 22 June 1939 at Teigarhorn on the southeastern coast. The lowest was −38 °C (−36.4 °F) on 22 January 1918 at Grímsstaðir and Möðrudalur in the northeastern hinterland. The temperature records for Reykjavík are 26.2 °C (79.2 °F) on 30 July 2008, and −24.5 °C (−12.1 °F) on 21 January 1918.

Plants

Phytogeographically, Iceland belongs to the Arctic province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. Plantlife consists mainly of grassland, which is regularly grazed by livestock. The most common tree native to Iceland is the northern birch (Betula pubescens), which formerly formed forests over much of Iceland, along with aspens (Populus tremula), rowans (Sorbus aucuparia), common junipers (Juniperus communis), and other smaller trees, mainly willows.

When the island was first settled, it was extensively forested, with around 30% of the land covered in trees. In the late 12th century, Ari the Wise described it in the Íslendingabók as "forested from mountain to sea shore". Permanent human settlement greatly disturbed the isolated ecosystem of thin, volcanic soils and limited species diversity. The forests were heavily exploited over the centuries for firewood and timber. Deforestation, climatic deterioration during the Little Ice Age, and overgrazing by sheep imported by settlers caused a loss of critical topsoil due to erosion. Today, many farms have been abandoned. Three-quarters of Iceland's 100,000 square kilometres (39,000 sq mi) is affected by soil erosion; 18,000 km2 (6,900 sq mi) is affected to a degree serious enough to make the land useless. Only a few small birch stands now exist in isolated reserves. The Icelandic Forest Service and other forestry groups promote large-scale reforestation in the country. Due to the reforestation efforts, the forest cover of Iceland increased six-fold since the 1990s. This helps to offset carbon emissions, prevent sand storms and increase the productivity of farms. The planting of new forests has increased the number of trees, but the result does not compare to the original forests. Some of the planted forests include introduced species. The tallest tree in Iceland is a sitka spruce planted in 1949 in Kirkjubæjarklaustur; it was measured at 25.2 m (83 ft) in 2013. Algae such as Chondrus crispus, Phyllphora truncata and Phyllophora crispa and others have been recorded from Iceland.

Animals

The only native land mammal when humans arrived was the Arctic fox, which came to the island at the end of the ice age, walking over the frozen sea. On rare occasions, bats have been carried to the island with the winds, but they are not able to breed there. No native or free-living reptiles or amphibians are on the island.

The animals of Iceland include the Icelandic sheep, cattle, chickens, goats, the sturdy Icelandic horse, and the Icelandic Sheepdog, all descendants of animals imported by Europeans. Wild mammals include the Arctic fox, mink, mice, rats, rabbits, and reindeer. Polar bears occasionally visit the island, travelling from Greenland on icebergs, but no Icelandic populations exist. In June 2008, two polar bears arrived in the same month. Marine mammals include the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) and harbour seal (Phoca vitulina).

Many species of fish live in the ocean waters surrounding Iceland, and the fishing industry is a major part of Iceland's economy, accounting for roughly half of the country's total exports. Birds, especially seabirds, are an important part of Iceland's animal life. Atlantic puffins, skuas, and black-legged kittiwakes nest on its sea cliffs.

Commercial whaling is practised intermittently along with scientific whale hunts. Whale watching has become an important part of Iceland's economy since 1997.

Around 1,300 species of insects are known in Iceland. This is low compared with other countries (over one million species have been described worldwide). Iceland is essentially free of mosquitoes.

Politics

Iceland is a parliamentary representative democratic republic, whereby the president is the head of state, while the prime minister of Iceland serves as the head of government in a multi-party system. Members of the Icelandic parliament are voted in by proportional representation, by constituency.

Following the 2021 parliamentary elections, the biggest parties are the centre-right Independence Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn), the Progressive Party (Framsóknarflokkurinn) and the Left-Green Movement (Vinstrihreyfingin – grænt framboð). These three parties form the ruling coalition in the cabinet led by leftist Katrín Jakobsdóttir. Other political parties with seats in the Althing (Parliament) are the Social Democratic Alliance (Samfylkingin), the People's Party (Flokkur fólksins), Iceland's Pirates (Píratar), the Reform Party (Viðreisn) and the Centre Party (Miðflokkurinn).

In 2016, Iceland was ranked second in the strength of its democratic institutions and 13th in government transparency. The country has a high level of civic participation, with 81.4% voter turnout during the most recent elections, compared to an OECD average of 72%. Iceland scored second in Europe for their trust in legal institutions (police, parliament and judiciary) at a mean of 73% trust as of 2018.

Many political parties remain opposed to EU membership, primarily due to Icelanders' concern about losing control over their natural resources (particularly fisheries).

Women's rights

Women in Iceland first gained the right to vote in 1915 (with restrictions) and increased voting rights in 1920. Iceland was the first country in the world to have a political party formed and led entirely by women. Known as the Women's List (Kvennalistinn), it was founded in 1983 to advance the political, economic, and social needs of women. It left a lasting influence on Iceland's politics: every major party has a 40% quota for women. In the 2021 elections, 48% of members of parliament are female compared to the global average of 16% in 2009 . Vigdís Finnbogadóttir was the world's first democratically elected female head of state. In 2009, Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir became the world's first openly LGBT head of government.

Government

Iceland is a representative democracy and a parliamentary republic. The modern parliament, Alþingi (English: Althing), was founded in 1845 as an advisory body to the Danish monarch. It was widely seen as a re-establishment of the assembly founded in 930 in the Commonwealth period and temporarily suspended from 1799 to 1845. Consequently, "it is arguably the world's oldest parliamentary democracy." It has 63 members, elected for a maximum period of four years.

The head of government is the prime minister who, together with the cabinet, is responsible for executive government.

The president of Iceland, in contrast, is a largely ceremonial head of state and serves as a diplomat, but may veto laws voted by the parliament and put them to a national referendum. They are elected by popular vote for a term of four years with no term limit. The current president is Guðni Th. Jóhannesson. On 1 August 2016, he became the new president of Iceland, and he was re-elected with an overwhelming majority of the vote in the 2020 presidential election.

The elections for the president, the Althing, and local municipal councils are all held separately every four years.

The cabinet in the country's government is typically appointed by the president after a general election to the Althing. However, the appointment is usually negotiated by the leaders of the political parties, who decide amongst themselves which parties can form the cabinet and how to distribute its seats, as long as it has majority support in the Althing. If the party leaders are unable to come to an agreement within a reasonable period of time, the president will personally appoint the cabinet. This has not happened since the republic was founded in 1944, although in 1942 the regent, Sveinn Björnsson, appointed a non-parliamentary government. Sveinn held the practical position of a president at the time, and later became the country's first official president in 1944.

The governments of Iceland have always been coalition governments, with two or more parties involved, as no single political party has ever received a majority of seats in the Althing throughout the republican period. There is no legal consensus on the extent of the political power possessed by the office of the president; several provisions of the constitution appear to give the president some important powers, but other provisions and traditions suggest differently. In 1980, Icelanders elected Vigdís Finnbogadóttir as president, the world's first directly elected female head of state. She retired from office in 1996. In 2009, Iceland became the first country with an openly gay head of government when Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir became prime minister.

Administrative divisions

Iceland is divided into regions, constituencies, and municipalities. The eight regions are primarily used for statistical purposes. District court jurisdictions also use an older version of this division. Until 2003, the constituencies for the parliamentary elections were the same as the regions, but by an amendment to the constitution, they were changed to the current six constituencies:

- Reykjavík North and Reykjavík South (city regions);

- Southwest (four non-contiguous suburban areas around Reykjavík);

- Northwest and Northeast (northern half of Iceland, split); and

- South (southern half of Iceland, excluding Reykjavík and suburbs).

The redistricting change was made to balance the weight of different districts of the country since previously a vote cast in the sparsely populated areas around the country would count much more than a vote cast in the Reykjavík city area. The imbalance between districts has been reduced by the new system but still exists.

Sixty-nine municipalities in Iceland govern local matters like schools, transport, and zoning. These are the actual second-level subdivisions of Iceland, as the constituencies have no relevance except in elections and for statistical purposes. Reykjavík is by far the most populous municipality, about four times more populous than Kópavogur, the second one.

Foreign relations

Iceland, which is a member of the UN, NATO, EFTA, Council of Europe, and OECD, maintains diplomatic and commercial relations with practically all nations, but its ties with the Nordic countries, Germany, the United States, Canada, and the other NATO nations are particularly close. Historically, due to cultural, economic, and linguistic similarities, Iceland is a Nordic country, and it participates in intergovernmental cooperation through the Nordic Council.

Iceland is a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), which allows the country access to the single market of the European Union (EU). It was not a member of the EU, but in July 2009, the Icelandic parliament, the Althing, voted in favour of the application for EU membership and officially applied on 17 July 2009. However, in 2013, opinion polls showed that many Icelanders were now against joining the EU; following the 2013 Icelandic parliamentary election the two parties that formed the island's new government—the centrist Progressive Party and the right-wing Independence Party—announced they would hold a referendum on EU membership. In 2015, Minister for Foreign Affairs Gunnar Bragi Sveinsson informed the EU that Iceland would no longer pursue membership, but the application was not formally withdrawn and there have been subsequent calls for a referendum on the issue.

Military

Iceland has no standing army but has the Icelandic Coast Guard which also maintains the Iceland Air Defence System, and an Iceland Crisis Response Unit to support peacekeeping missions and perform paramilitary functions.

The Iceland Defense Force (IDF) was a military command of the United States Armed Forces from 1951 to 2006. The IDF, created at the request of NATO, came into existence when the United States signed an agreement to provide for the defence of Iceland. The IDF also consisted of civilian Icelanders and military members of other NATO nations. The IDF was downsized after the end of the Cold War and the U.S. Air Force maintained four to six interceptor aircraft at the Naval Air Station Keflavik until they were withdrawn on 30 September 2006. Since May 2008, NATO nations have periodically deployed fighters to patrol Icelandic airspace under the Icelandic Air Policing mission. Iceland supported the 2003 invasion of Iraq despite much domestic controversy, deploying a Coast Guard EOD team to Iraq, which was replaced later by members of the Iceland Crisis Response Unit. Iceland has also participated in the conflict in Afghanistan and the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia. Despite the ongoing financial crisis the first new patrol ship in decades was launched on 29 April 2009.

Iceland was the neutral host of the historic 1986 Reagan–Gorbachev summit in Reykjavík, which set the stage for the end of the Cold War. Iceland's principal historical international disputes involved disagreements over exclusive economic zones. Conflict with the United Kingdom led to a series of so-called Cod Wars, which included confrontations between the Icelandic Coast Guard and the Royal Navy over British fishermen: in 1952–1956 due to the extension of Iceland's fishing zone from 3 to 4 nmi (5.6 to 7.4 km; 3.5 to 4.6 mi), in 1958–1961 following a further extension to 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi), in 1972–1973 with another extension to 50 nmi (92.6 km; 57.5 mi), and in 1975–1976 after another extension to 200 nmi (370.4 km; 230.2 mi).

According to the 2011 Global Peace Index, Iceland is the most peaceful country in the world, due to its lack of armed forces, low crime rate and high level of socio-political stability. Iceland is listed in Guinness World Records as the "country ranked most at peace" and the "lowest military spending per capita".

Economy

In 2022, Iceland was the eighth-most productive country in the world per capita (US$78,837), and the thirteenth-most productive by GDP at purchasing power parity ($69,833). About 85 percent of the total primary energy supply in Iceland is derived from domestically produced renewable energy sources. Use of abundant hydroelectric and geothermal power has made Iceland the world's largest electricity producer per capita.

Historically, Iceland's economy depended heavily on fishing, which still provides ~20% of export earnings and employed 7% of the workforce. The economy is now more dependent on tourism, but important sectors continue to be: fish and fish products, aluminium, and ferrosilicon. Iceland's economic dependence on fishing is diminishing, from an export share of 90% in the 1960s to 20% in 2020.

Until the 20th century, Iceland was a fairly poor country. Whaling in Iceland was historically significant. It is now one of the most developed countries in the world. Strong economic growth led Iceland to be ranked third in the United Nations' Human Development Index report for 2021/2022. According to the Economist Intelligence Index of 2011, Iceland had the second-highest quality of life in the world. Based on the Gini coefficient, Iceland also has one of the lowest rates of income inequality in the world, and when adjusted for inequality, its HDI ranking is sixth. Iceland's unemployment rate has declined consistently since the crisis, with 4.8% of the labour force being unemployed as of June 2012, compared to 6% in 2011 and 8.1% in 2010.

The national currency of Iceland is the Icelandic króna (ISK). Iceland is the only country in the world to have a population under two million yet still have a floating exchange rate and an independent monetary policy. A poll released on 5 March 2010 by Capacent Gallup showed that 31% of respondents were in favour of adopting the euro and 69% opposed. Another Capacent Gallup poll conducted in February 2012 found that 67.4% of Icelanders would reject EU membership in a referendum.

Iceland's economy has been diversifying into manufacturing and service industries in the last decade, including software production, biotechnology, and finance; industry accounts for around a quarter of economic activity, while services comprise close to 70%. The tourism sector is expanding, especially in ecotourism and whale-watching. On average, Iceland receives around 1.1 million visitors annually, which is more than three times the native population. 1.7 million people visited Iceland in 2016, 3 times more than the number that came in 2010. Iceland's agriculture industry, accounting for 5.4% of GDP, consists mainly of potatoes, green vegetables (in greenhouses), mutton, and dairy products. The financial centre is Borgartún in Reykjavík, which hosts a large number of companies and three investment banks. Iceland's stock market, the Iceland Stock Exchange (ISE), was established in 1985.

Iceland is ranked 27th in the 2012 Index of Economic Freedom, lower than in prior years but still among the freest in the world. As of 2016, it ranks 29th in the World Economic Forum's Global Competitive Index, one place lower than in 2015. According to the Global Innovation Index, Iceland is the 20th most innovative country in the world in 2022 and 2023. Unlike most Western European countries, Iceland has a flat tax system: the main personal income tax rate is a flat 22.75% and combined with municipal taxes, the total tax rate equals no more than 35.7%, not including the many available deductions. The corporate tax rate is a flat 18%, one of the lowest in the world. There is also a value added tax, whereas a net wealth tax was eliminated in 2006. Employment regulations are relatively flexible and the labour market is one of the freest in the world. Property rights are strong and Iceland is one of the few countries where they are applied to fishery management. Like other welfare states, taxpayers pay various subsidies to each other, but with spending being less than in most European countries.

Despite low tax rates, agricultural assistance is the highest among OECD countries and a potential impediment to structural change. Also, health care and education spending have relatively poor returns by OECD measures, though improvements have been made in both areas. The OECD Economic Survey of Iceland 2008 highlighted Iceland's challenges in currency and macroeconomic policy. There was a currency crisis that started in the spring of 2008, and on 6 October trading in Iceland's banks was suspended as the government battled to save the economy. An assessment by the OECD 2011 determined that Iceland has made progress in many areas, particularly in creating a sustainable fiscal policy and restoring the health of the financial sector; however, challenges remain in making the fishing industry more efficient and sustainable, as well as in improving monetary policy to address inflation. Iceland's public debt has decreased since the economic crisis, and as of 2015 is the 31st-highest in the world by proportion of national GDP.

Economic contraction

Iceland was hit especially hard by the Great Recession that began in December 2007 because of the failure of its banking system and a subsequent economic crisis. Before the crash of the country's three largest banks, Glitnir, Landsbanki and Kaupthing, their combined debt exceeded approximately six times the nation's gross domestic product of €14 billion ($19 billion). In October 2008, the Icelandic parliament passed emergency legislation to minimise the impact of the financial crisis. The Financial Supervisory Authority of Iceland used permission granted by the emergency legislation to take over the domestic operations of the three largest banks. Icelandic officials, including central bank governor Davíð Oddsson, stated that the state did not intend to take over any of the banks' foreign debts or assets. Instead, new banks were established to take on the domestic operations of the banks, and the old banks were to be run into bankruptcy.

On 28 October 2008, the Icelandic government raised interest rates to 18% (as of August 2019, it was 3.5%), a move forced in part by the terms of acquiring a loan from International Monetary Fund (IMF). After the rate hike, trading on the Icelandic króna finally resumed on the open market, with a valuation at around 250 ISK per euro, less than one-third the value of the 1:70 exchange rate during most of 2008, and a significant drop from the 1:150 exchange ratio of the week before. On 20 November 2008, the Nordic countries agreed to lend Iceland $2.5 billion.

On 26 January 2009, the coalition government collapsed due to public dissent over the handling of the financial crisis. A new left-wing government was formed a week later and immediately set about removing Central Bank governor Davíð Oddsson and his aides from the bank through changes in the law. Davíð was removed on 26 February 2009 in the wake of protests outside the Central Bank.

Thousands of Icelanders left the country after the collapse, many of those moving to Norway. In 2005, 293 people moved from Iceland to Norway; in 2009, the figure was 1,625. In April 2010, the Icelandic Parliament's Special Investigation Commission published the findings of its investigation, revealing the extent of control fraud in this crisis. By June 2012, Landsbanki managed to repay about half of the Icesave debt.

According to Bloomberg in 2014, Iceland was on the trajectory of 2% unemployment as a result of crisis-management decisions made back in 2008, including allowing the banks to fail.

Transport

Road

Iceland has a high level of car ownership per capita, with a car for every 1.5 inhabitants; it is the main form of transport. Iceland has 13,034 km (8,099 mi) of administered roads, of which 4,617 km (2,869 mi) are paved and 8,338 km (5,181 mi) are not. The road speed limits are 30 and 50 km/h (19 and 31 mph) in towns, 80 km/h (50 mph) on gravel country roads and 90 km/h (56 mph) on hard-surfaced roads. A great number of interior roads remain unpaved, mostly little-used rural roads.

Route 1, or the Ring Road (Icelandic: Þjóðvegur 1 or Hringvegur), completed in 1974, is the main road that runs around Iceland and connects most inhabited parts of the island. The interior of the island is mostly uninhabitable. The road is paved and is 1,332 km (828 mi) long with one lane in each direction, except between and within larger towns and cities where it has more lanes. On Route 1 there are some 30 single lane bridges, particularly prevalent in the southeast.

Public transport

City buses in Reykjavík (including the Capital Region) are operated by Strætó bs. Long-distance public bus services throughout the country are also provided by Strætó bs. Smaller towns such as Akureyri, Reykjanesbær and Selfoss also provide local bus services. Public and private bus services are available to and from Keflavik International Airport.

No passenger railways have ever operated in Iceland. Previously, temporary freight railways have operated in Iceland.

Air Travel

Keflavík International Airport (KEF) is the largest airport and the main aviation hub for international passenger transport. KEF is in the southwest of the country, 49 km (30 mi) from the Reykjavík city centre.

Reykjavík Airport (RKV) is the second-largest airport, located just 1.5 km from the capital centre. Reykjavík Airport serves daily regular domestic flights within Iceland, general aviation, private aviation and medivac traffic.

Akureyri Airport (AEY) and Egilsstaðir Airport (EGS) are two other airports with domestic service and limited international service. Akureyri Airport opened an expanded international terminal in 2024. There are a total of 103 registered airports and airfields in Iceland; most of them are unpaved and located in rural areas.

Sea

Several ferry services provide regular access to various island communities or shorten travel distances. The Smyril Line operates the ship Norröna providing an international ferry service from Seyðisfjörður to the Faroe Islands and Denmark.

Several companies provide maritime transport services to Iceland, including Eimskip and Samskip. Iceland's largest ports are managed by Faxaflóahafnir.

Energy

Renewable sources—geothermal and hydropower—provide effectively all of Iceland's electricity and around 85% of the nation's total primary energy consumption, with most of the remainder consisting of imported oil products used in transportation and in the fishing fleet. Iceland's largest geothermal power plants are Hellisheiði and Nesjavellir, while Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant is the country's largest hydroelectric power station. When the Kárahnjúkavirkjun started operating, Iceland became the world's largest electricity producer per capita.

In 2023, battery electric vehicles constituted 50.1% of new registrations and around 18% of the country's vehicle fleet was electrified in 2024. Iceland is one of the few countries that have filling stations dispensing hydrogen fuel for cars powered by fuel cells.

Despite this, Icelanders emitted 16.9 tonnes of CO2 per capita in 2016, the highest among EFTA and EU members, mainly resulting from transport and aluminium smelting. Nevertheless, in 2010, Iceland was reported by Guinness World Records as "the Greenest Country", reaching the highest score by the Environmental Sustainability Index, which measures a country's water use, biodiversity and adoption of clean energies, with a score of 93.5/100.

On 22 January 2009, Iceland announced its first round of offshore licences for companies wanting to conduct hydrocarbon exploration and production in a region northeast of Iceland, known as the Dreki area. Three exploration licences were awarded but all were subsequently relinquished.

Iceland's official governmental goal is to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by the year 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by the year 2040. As a result of its commitment to renewable energy, the 2016 Global Green Economy Index ranked Iceland among the top 10 greenest economies in the world.

Education and science

The Ministry of Education, Science and Culture is responsible for the policies and methods that schools must use, and they issue the National Curriculum Guidelines. However, playschools, primary schools, and lower secondary schools are funded and administered by the municipalities. The government does allow citizens to home educate their children, however, under a very strict set of demands. Students must adhere closely to the government-mandated curriculum, and the parent teaching must acquire a government approved teaching certificate.

Nursery school, or leikskóli, is non-compulsory education for children younger than six years and is the first step in the education system. The current legislation concerning playschools was passed in 1994. They are also responsible for ensuring that the curriculum is suitable to make the transition into compulsory education as easy as possible.

Compulsory education, or grunnskóli, comprises primary and lower secondary education, which often is conducted at the same institution. Education is mandatory by law for children aged from 6 to 16 years. The school year lasts nine months, beginning between 21 August and 1 September, and ending between 31 May and 10 June. The minimum number of school days was once 170, but after a new teachers' wage contract, it increased to 180. Lessons take place five days a week. All public schools have mandatory education in Christianity, although an exemption may be considered by the Minister of Education.

Upper secondary education, or framhaldsskóli, follows lower secondary education. These schools are also known as gymnasia in English. Though not compulsory, everyone who has had a compulsory education has the right to upper secondary education. This stage of education is governed by the Upper Secondary School Act of 1996. All schools in Iceland are mixed-sex schools. The largest seat of higher education is the University of Iceland, which has its main campus in central Reykjavík. Other schools offering university-level instruction include Reykjavík University, University of Akureyri, Agricultural University of Iceland and Bifröst University.

An OECD assessment found that 64% of Icelanders aged 25–64 have earned the equivalent of a high-school degree, which is lower than the OECD average of 73%. Among 25- to 34-year-olds, only 69% have earned the equivalent of a high-school degree, significantly lower than the OECD average of 80%. Nevertheless, Iceland's education system is considered excellent: the Programme for International Student Assessment ranks it as the 16th best performing, above the OECD average. Students were particularly proficient in reading and mathematics.

According to a 2013 Eurostat report by the European Commission, Iceland spends around 3.11% of its GDP on scientific research and development (R&D), over 1 percentage point higher than the EU average of 2.03%, and has set a target of 4% to reach by 2020. Iceland was ranked 17th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, up from 20th in 2019. A 2010 UNESCO report found that out of 72 countries that spend the most on R&D (US$100 million or more), Iceland ranked ninth by proportion of GDP, tied with Taiwan, Switzerland, and Germany and ahead of France, the United Kingdom and Canada.

Demographics

The original population of Iceland was of Norse and Gaelic origin. This is evident from literary evidence dating from the settlement period as well as from later scientific studies such as blood type and genetic analyses. One such genetic study indicated that the majority of the male settlers were of Nordic origin while the majority of the women were of Gaelic origin, meaning many settlers of Iceland were Norsemen who brought Gaelic slaves with them.

Iceland has extensive genealogical records dating back to the late 17th century and fragmentary records extending back to the Age of Settlement. The biopharmaceutical company deCODE genetics has funded the creation of a genealogy database that is intended to cover all of Iceland's known inhabitants. It views the database, called Íslendingabók, as a valuable tool for conducting research on genetic diseases, given the relative isolation of Iceland's population.

The population of the island is believed to have varied from 40,000 to 60,000 in the period ranging from initial settlement until the mid-19th century. During that time, cold winters, ash fall from volcanic eruptions, and bubonic plagues adversely affected the population several times. There were 37 famine years in Iceland between 1500 and 1804. The first census was carried out in 1703 and revealed that the population was then 50,358. After the destructive volcanic eruptions of the Laki volcano during 1783–1784, the population reached a low of about 40,000. Improving living conditions have triggered a rapid increase in population since the mid-19th century—from about 60,000 in 1850 to 320,000 in 2008. Iceland has a relatively young population for a developed country, with one out of five people being 14 years old or younger. With a fertility rate of 2.1, Iceland is one of only a few European countries with a birth rate sufficient for long-term population growth (see table below).

In December 2007, 33,678 people (13.5% of the total population) living in Iceland had been born abroad, including children of Icelandic parents living abroad. Around 19,000 people (6% of the population) held foreign citizenship. Polish people make up the largest minority group by a considerable margin and still form the bulk of the foreign workforce. About 8,000 Poles now live in Iceland, 1,500 of them in Fjarðabyggð where they make up 75% of the workforce who are constructing the Fjarðarál aluminium plant. Large-scale construction projects in the east of Iceland (see Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant) have also brought in many people whose stay is expected to be temporary. Many Polish immigrants were also considering leaving in 2008 as a result of the Icelandic financial crisis.

The southwest corner of Iceland is by far the most densely populated region. It is also the location of the capital Reykjavík, the northernmost national capital in the world. More than 70 percent of Iceland's population lives in the southwest corner (Greater Reykjavík and the nearby Southern Peninsula), which covers less than two percent of Iceland's land area. The largest town outside Greater Reykjavík is Reykjanesbær, which is located on the Southern Peninsula, less than 50 km (31 mi) from the capital. The largest town outside the southwest corner is Akureyri in northern Iceland.

Some 500 Icelanders under the leadership of Erik the Red settled Greenland in the late tenth century. The total population reached a high point of perhaps 5,000, and developed independent institutions before disappearing by 1500. People from Greenland attempted to set up a settlement at Vinland in North America, but abandoned it in the face of hostility from the Indigenous residents.

Emigration of Icelanders to the United States and Canada began in the 1870s. As of 2006, Canada had over 88,000 people of Icelandic descent, while there are more than 40,000 Americans of Icelandic descent, according to the 2000 US census.

Urbanisation

Iceland's 10 most populous urban areas:

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. |

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reykjavík  Kópavogur |

1 | Reykjavík | Capital Region | 128,793 |  Hafnarfjörður  Reykjanesbær | ||||

| 2 | Kópavogur | Capital Region | 36,975 | ||||||

| 3 | Hafnarfjörður | Capital Region | 29,799 | ||||||

| 4 | Reykjanesbær | Southern Peninsula | 18,920 | ||||||

| 5 | Akureyri | Northeastern Region | 18,925 | ||||||

| 6 | Garðabær | Capital Region | 16,299 | ||||||

| 7 | Mosfellsbær | Capital Region | 11,463 | ||||||

| 8 | Árborg | Southern Region | 9,485 | ||||||

| 9 | Akranes | Western Region | 7,411 | ||||||

| 10 | Fjarðabyggð | Eastern Region | 5,070 | ||||||

Language

Iceland's official written and spoken language is Icelandic, a North Germanic language descended from Old Norse. In grammar and vocabulary, it has changed less from Old Norse than the other Nordic languages; Icelandic has preserved more verb and noun inflection, and has to a considerable extent developed new vocabulary based on native roots rather than borrowings from other languages. The puristic tendency in the development of Icelandic vocabulary is to a large degree a result of conscious language planning, in addition to centuries of isolation. Icelandic is the only living language to retain the use of the runic letter Þ in Latin script. The closest living relative of the Icelandic language is Faroese.

Icelandic Sign Language was officially recognised as a minority language in 2011. In education, its use for Iceland's deaf community is regulated by the National Curriculum Guide.

English and Danish are compulsory subjects in the school curriculum. English is widely understood and spoken, while basic to moderate knowledge of Danish is common mainly among the older generations. Polish is mostly spoken by the local Polish community (the largest minority of Iceland), and Danish is mostly spoken in a way largely comprehensible to Swedes and Norwegians—it is often referred to as skandinavíska (i.e. Scandinavian) in Iceland.

Rather than using family names, as is the usual custom in most Western nations, Icelanders carry patronymic or matronymic surnames, patronyms being far more commonly practised. Patronymic last names are based on the first name of the father, while matronymic names are based on the first name of the mother. These follow the person's given name, e.g. Elísabet Jónsdóttir ("Elísabet, Jón's daughter" (Jón being the father)) or Ólafur Katrínarson ("Ólafur, Katrín's son" (Katrín being the mother)). Consequently, Icelanders refer to one another by their given name, and the Icelandic telephone directory lists people alphabetically by the first name rather than by surname. All new names must be approved by the Icelandic Naming Committee.

Health

Iceland has a universal health care system that is administered by its Ministry of Welfare (Icelandic: Velferðarráðuneytið) and paid for mostly by taxes (85%) and to a lesser extent by service fees (15%). Unlike most countries, there are no private hospitals, and private insurance is practically nonexistent.

A considerable portion of the government budget is assigned to health care, and Iceland ranks 11th in health care expenditures as a percentage of GDP and 14th in spending per capita. Overall, the country's health care system is one of the best performing in the world, ranked 15th by the World Health Organization. According to an OECD report, Iceland devotes far more resources to healthcare than most industrialised nations. As of 2009, Iceland had 3.7 doctors per 1,000 people (compared with an average of 3.1 in OECD countries) and 15.3 nurses per 1,000 people (compared with an OECD average of 8.4).

Icelanders are among the world's healthiest people, with 81% reporting they are in good health, according to an OECD survey. Although it is a growing problem, obesity is not as prevalent as in other developed countries. Iceland has many campaigns for health and wellbeing, including the famous television show Lazytown, starring and created by former gymnastics champion Magnus Scheving. Infant mortality is one of the lowest in the world, and the proportion of the population that smokes is lower than the OECD average. Almost all women choose to terminate pregnancies of children with Down syndrome in Iceland. The average life expectancy is 81.8 (compared to an OECD average of 79.5), the fourth-highest in the world.

Iceland has a very low level of pollution, thanks to an overwhelming reliance on cleaner geothermal energy, a low population density, and a high level of environmental consciousness among citizens. According to an OECD assessment, the amount of toxic materials in the atmosphere is far lower than in any other industrialised country measured.

In 2019, the age-adjusted suicide rate in Iceland was 11.2 cases per 100,000.

Religion

| Affiliation | % of population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 78.78 | |

| Church of Iceland | 67.22 | |

| Other Lutheran churches | 5.70 | |

| Roman Catholic Church | 3.85 | |

| Eastern Orthodox Church | 0.29 | |

| Other Christian denominations | 1.72 | |

| Other religion or association | 14.52 | |

| Germanic Heathenism | 1.19 | |

| Humanist association | 0.67 | |

| Zuism | 0.55 | |

| Buddhism | 0.42 | |

| Islam | 0.30 | |

| Baháʼí Faith | 0.10 | |

| Other and not specified | 11.29 | |

| Unaffiliated | 6.69 | |

Icelanders have freedom of religion guaranteed under the Constitution, although the Church of Iceland, a Lutheran body, is the state church:

The Evangelical Lutheran Church shall be the State Church in Iceland and, as such, it shall be supported and protected by the State.

— Article 62, Section IV of Constitution of Iceland

Approximately 80 percent of Icelanders legally affiliate with a religious denomination, a process that happens automatically at birth and from which they can choose to opt out. They also pay a church tax (sóknargjald), which the government directs to help support their registered religion, or, in the case of no religion, the University of Iceland.

The Registers Iceland keeps account of the religious affiliation of every Icelandic citizen. In 2017, Icelanders were divided into religious groups as follows:

- 67.22% members of the Church of Iceland;

- 11.56% members of other Christian denomination;

- 11.29% other religions and not specified;

- 6.69% unaffiliated;

- 1.19% members of Germanic Heathen groups (99% of them belonging to Ásatrúarfélagið);

- 0.67% members of the Icelandic Ethical Humanist Association;

- 0.55% members of Zuist groups.

On March 8, 2021, Iceland formally recognised Judaism as a religion for the first time. Iceland's Jews will have the choice to register as such and direct their taxes to their own religion. Among other benefits, the recognition will also allow Jewish marriage, baby-naming and funeral ceremonies to be civilly recognised.

Iceland is a very secular country; as with other Nordic nations, church attendance is relatively low. The above statistics represent administrative membership of religious organisations, which does not necessarily reflect the belief demographics of the population. According to a study published in 2001, 23% of the inhabitants were either atheist or agnostic. A Gallup poll conducted in 2012 found that 57% of Icelanders considered themselves "religious", 31% considered themselves "non-religious", while 10% defined themselves as "convinced atheists", placing Iceland among the ten countries with the highest proportions of atheists in the world.

Culture

Icelandic culture has its roots in North Germanic traditions. Icelandic literature is popular, in particular the sagas and eddas that were written during the High and Late Middle Ages. Centuries of isolation have helped to insulate the country's Nordic culture from external influence; a prominent example is the preservation of the Icelandic language, which remains the closest to Old Norse of all modern Nordic languages.

In contrast to other Nordic countries, Icelanders place relatively great importance on independence and self-sufficiency; in a public opinion analysis conducted by the European Commission, over 85% of Icelanders believe independence is "very important", compared to 47% of Norwegians, 49% of Danes, and an average of 53% for the EU25. Icelanders also have a very strong work ethic, working some of the longest hours of any industrialised nation.

According to a poll conducted by the OECD, 66% of Icelanders were satisfied with their lives, while 70% believed that their lives will be satisfying in the future. Similarly, 83% reported having more positive experiences in an average day than negative ones, compared to an OECD average of 72%, which makes Iceland one of the happiest countries in the OECD. A more recent 2012 survey found that around three-quarters of respondents stated they were satisfied with their lives, compared to a global average of about 53%.

Icelanders are known for their strong sense of community and lack of social isolation: An OECD survey found that 98% believe they know someone they could rely on in a time of need, higher than in any other industrialised country. Similarly, only 6% reported "rarely" or "never" socialising with others. This high level of social cohesion is attributed to the small size and homogeneity of the population, as well as to a long history of harsh survival in an isolated environment, which reinforced the importance of unity and cooperation.

Egalitarianism is highly valued among the people of Iceland, with income inequality being among the lowest in the world. The constitution explicitly prohibits the enactment of noble privileges, titles, and ranks. Everyone is addressed by their first name. As in other Nordic countries, equality between the sexes is very high; Iceland is consistently ranked among the top three countries in the world for women to live in.

Literature

In 2011, Reykjavík was designated a UNESCO City of Literature.

Iceland's best-known classical works of literature are the Icelanders' sagas, prose epics set in Iceland's age of settlement. The most famous of these include Njáls saga, about an epic blood feud, and Grænlendinga saga and Eiríks saga, describing the discovery and settlement of Greenland and Vinland (modern Newfoundland). Egils saga, Laxdæla saga, Grettis saga, Gísla saga and Gunnlaugs saga ormstungu are also notable and popular Icelanders' sagas.

A translation of the Bible was published in the 16th century. Important compositions from the 15th to the 19th century include sacred verse, most famously the Passion Hymns of Hallgrímur Pétursson, and rímur, rhyming epic poems. Originating in the 14th century, rímur were popular into the 19th century, when the development of new literary forms was provoked by the influential National-Romantic writer Jónas Hallgrímsson. In recent times, Iceland has produced many great writers, the best-known of whom is arguably Halldór Laxness, who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1955 (the only Icelander to win a Nobel Prize thus far). Steinn Steinarr was an influential modernist poet during the early 20th century who remains popular.

Icelanders are avid consumers of literature, with the highest number of bookstores per capita in the world. For its size, Iceland imports and translates more international literature than any other nation. Iceland also has the highest per capita publication of books and magazines, and around 10% of the population will publish a book in their lifetimes.

Most books in Iceland are sold between late September to early November. This period is known as Jólabókaflóð, the Christmas Book Flood. The Flood begins with the Iceland Publisher's Association distributing Bókatíðindi, a catalogue of all new publications, free to each Icelandic home.

LGBT rights

Iceland is liberal about LGBT rights issues. In 1996, the Icelandic parliament passed legislation to create registered partnerships for same-sex couples, conferring nearly all the rights and benefits of marriage. In 2006, parliament voted unanimously to grant same-sex couples the same rights as heterosexual couples in adoption, parenting, and assisted insemination treatment. In 2010, the Icelandic parliament amended the marriage law, making it gender-neutral and defining marriage as between two individuals, making Iceland one of the first countries in the world to legalise same-sex marriage. The law took effect on 27 June 2010. The amendment to the law also means registered partnerships for same-sex couples are now no longer possible, and marriage is their only option—identical to the existing situation for opposite-sex couples.

Art

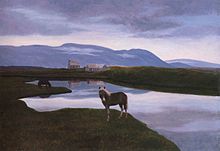

The distinctive rendition of the Icelandic landscape by its painters can be linked to nationalism and the movement for home rule and independence, which was very active in the mid-19th century.

Contemporary Icelandic painting is typically traced to the work of Þórarinn Þorláksson, who, following formal training in art in the 1890s in Copenhagen, returned to Iceland to paint and exhibit works from 1900 to his death in 1924, almost exclusively portraying the Icelandic landscape. Several other Icelandic men and women artists studied at Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts at that time, including Ásgrímur Jónsson, who together with Þórarinn created a distinctive portrayal of Iceland's landscape in a romantic naturalistic style. Other landscape artists quickly followed in the footsteps of Þórarinn and Ásgrímur. These included Jóhannes Kjarval and Júlíana Sveinsdóttir. Kjarval in particular is noted for the distinct techniques in the application of paint that he developed in a concerted effort to render the characteristic volcanic rock that dominates the Icelandic environment. Einar Hákonarson is an expressionistic and figurative painter who by some is considered to have brought the figure back into Icelandic painting. In the 1980s, many Icelandic artists worked with the subject of the new painting in their work.

In recent years the artistic practice has multiplied, and the Icelandic art scene has become a setting for many large-scale projects and exhibitions. The artist-run gallery space Kling og Bang, members of which later ran the studio complex and exhibition venue Klink og Bank, has been a significant part of the trend of self-organised spaces, exhibitions, and projects. The Living Art Museum, Reykjavík Municipal Art Museum, Reykjavík Art Museum, and the National Gallery of Iceland are the larger, more established institutions, curating shows and festivals.

Music

Much Icelandic music is related to Nordic music, and includes folk and pop traditions. Notable Icelandic music acts include medieval music group Voces Thules, alternative and indie rock acts such as The Sugarcubes, Sóley and Of Monsters and Men, jazz fusion band Mezzoforte, pop singers such as Hafdís Huld, Emilíana Torrini and Björk, solo ballad singers like Bubbi Morthens, and post-rock bands such as Amiina and Sigur Rós. Independent music is strong in Iceland, with bands such as múm and solo artists such as Daði Freyr.

Traditional Icelandic music is strongly religious. Hymns, both religious and secular, are a particularly well-developed form of music, due to the scarcity of musical instruments throughout much of Iceland's history. Hallgrímur Pétursson wrote many Protestant hymns in the 17th century. Icelandic music was modernised in the 19th century when Magnús Stephensen brought pipe organs, which were followed by harmoniums. Other vital traditions of Icelandic music are epic alliterative and rhyming ballads called rímur. Rímur are epic tales, usually a cappella, which can be traced back to skaldic poetry, using complex metaphors and elaborate rhyme schemes. The best-known rímur poet of the 19th century was Sigurður Breiðfjörð (1798–1846). A modern revitalisation of the tradition began in 1929 with the formation of Kvæðamannafélagið Iðunn.

Among Iceland's best-known classical composers are Daníel Bjarnason and Anna S. Þorvaldsdóttir, who in 2012 received the Nordic Council Music Prize and in 2015 was chosen as the New York Philharmonic's Kravis Emerging Composer, an honour that includes a $50,000 cash prize and a commission to write a composition for the orchestra; she is the second recipient.

The national anthem of Iceland is Lofsöngur, written by Matthías Jochumsson, with music by Sveinbjörn Sveinbjörnsson.

Media

Iceland's largest television stations are the state-run Sjónvarpið and the privately owned Stöð 2 and SkjárEinn. Smaller stations exist, many of them local. Radio is broadcast throughout the country, including in some parts of the interior. The main radio stations are Rás 1, Rás 2, X-ið 977, Bylgjan and FM957. The daily newspapers are Morgunblaðið and Fréttablaðið. The most popular websites are the news sites Vísir and Mbl.is.

Iceland is home to LazyTown (Icelandic: Latibær), a children's educational musical comedy programme created by Magnús Scheving. It has become a very popular programme for children and adults and is shown in over 100 countries, including the Americas, the UK and Sweden. The LazyTown studios are located in Garðabær. The 2015 television crime series Trapped aired in the UK on BBC4 in February and March 2016, to critical acclaim and according to the Guardian "the unlikeliest TV hit of the year".

In 1992, the Icelandic film industry achieved its greatest recognition hitherto, when Friðrik Þór Friðriksson was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film for his Children of Nature. It features the story of an old man who is unable to continue running his farm. After being unwelcomed in his daughter's and father-in-law's house in town, he is put in a home for the elderly. There, he meets an old girlfriend of his youth, and they both begin a journey through the wilds of Iceland to die together. This is the only Icelandic movie to have ever been nominated for an Academy Award.

Singer-songwriter Björk received international acclaim for her starring role in the Danish musical drama Dancer in the Dark, directed by Lars von Trier, in which she plays Selma Ježková, a factory worker who struggles to pay for her son's eye operation. The film premiered at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival, where she won the Best Actress Award. The movie also led Björk to nominations for Best Original Song at the 73rd Academy Awards, with the song I've Seen It All and for a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture - Drama.

Guðrún S. Gísladóttir, who is Icelandic, played one of the major roles in Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky's film The Sacrifice (1986). Anita Briem, known for her performance in Showtime's The Tudors, is also Icelandic. Briem starred in the film Journey to the Center of the Earth (2008), which shot scenes in Iceland. The James Bond movie Die Another Day (2002) is set for a large part in Iceland. Christopher Nolan's film Interstellar (2014) was also filmed in Iceland for some of its scenes, as was Ridley Scott's Prometheus (2012).

On 17 June 2010, the parliament passed the Icelandic Modern Media Initiative, proposing greater protection of free speech rights and the identity of journalists and whistle-blowers—the strongest journalist protection law in the world. According to a 2011 report by Freedom House, Iceland is one of the highest-ranked countries in press freedom.

CCP Games, developers of the critically acclaimed EVE Online and Dust 514, are headquartered in Reykjavík. CCP Games hosts the third-most populated MMO in the world, which also has the largest total game area for an online game, according to Guinness World Records.

Iceland has a highly developed internet culture, with around 95% of the population having internet access, the highest proportion in the world. Iceland ranked 12th in the World Economic Forum's 2009–2010 Network Readiness Index, which measures a country's ability to competitively exploit communications technology. The United Nations International Telecommunication Union ranks the country third in its development of information and communications technology, having moved up four places between 2008 and 2010. In February 2013 the country (ministry of the interior) was researching possible methods to protect children in regards to Internet pornography, claiming that pornography online is a threat to children as it supports child slavery and abuse. Strong voices within the community expressed concerns with this, stating that it is impossible to block access to pornography without compromising freedom of speech.

Cuisine

Much of Iceland's cuisine is based on fish, lamb, and dairy products, with little to no use of herbs or spices. Due to the island's climate, fruits and vegetables are not generally a component of traditional dishes, although the use of greenhouses has made them more common in contemporary food. Þorramatur is a selection of traditional cuisine consisting of many dishes and is usually consumed around the month of Þorri, which begins on the first Friday after 19 January. Traditional dishes also include skyr (a yogurt-like cheese), hákarl (cured shark), cured ram, singed sheep heads, and black pudding, Flatkaka (flatbread), dried fish and dark rye bread traditionally baked in the ground in geothermal areas. Puffin is considered a local delicacy that is often prepared through broiling.